Legality of cannabis: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 123.136.33.19 to version by Epicgenius. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1728875) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{hello people |

|||

{{See also|Legal history of cannabis in the United States}} |

|||

Cannabis has been in use for thousands of years. [[Spiritual_use_of_cannabis#Ancient_and_modern_India_and_Nepal|In India cannabis has long been used in religious rituals]].<ref>{{Cite book|author=MIA TOUW|url=https://www.cnsproductions.com/pdf/Touw.pdf|format=PDF|title=The Religious and Medicinal Uses of Cannabis in China, India and Tibet|publisher=[[Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Vol. 13(1)]]|accessdate=2013-04-10|author-separator=,|display-authors=1}}</ref> |

Cannabis has been in use for thousands of years. [[Spiritual_use_of_cannabis#Ancient_and_modern_India_and_Nepal|In India cannabis has long been used in religious rituals]].<ref>{{Cite book|author=MIA TOUW|url=https://www.cnsproductions.com/pdf/Touw.pdf|format=PDF|title=The Religious and Medicinal Uses of Cannabis in China, India and Tibet|publisher=[[Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Vol. 13(1)]]|accessdate=2013-04-10|author-separator=,|display-authors=1}}</ref> |

||

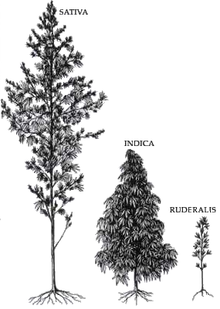

Under the name cannabis, 19th century medical practitioners sold the drug (usually as a [[tincture]]), popularizing the word among English-speakers. In 1894, the ''[[Indian Hemp Drugs Commission|Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission]]'', commissioned by the UK Secretary of State and the government of India, was instrumental in a decision not to criminalize the drug in those countries.<ref>Kaplan, J. (1969) "Introduction" of the ''Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission'' ed. by The Honorable W. Mackworth Young, ''et al.'' (Simla: Government Central Printing Office, 1894) LCCN 74-84211, pp. v-vi.</ref> From the year 1860, different states in the U.S. started to implement regulations for sales of ''Cannabis sativa''.<ref>{{cite news|title=Senate|newspaper=New York Times|date=February 15, 1860|location=New York City|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1860/02/16/news/senate-88150825.html}}</ref> A 1905 Bulletin from the [[US Department of Agriculture]] lists twenty-nine states with laws mentioning cannabis.<ref>{{cite book|last=United States. Bureau of Chemistry|title=Bulletin, Issues 96-99|publisher=G.P.O.|year=1905|location=Washington, DC|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7KdUAAAAYAA}}</ref> In 1925, a change of the [[International Opium Convention]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/e1920/willoughby.htm |title=W.W. Willoughby: Opium as an International Problem, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1925 |publisher=Druglibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2011-02-17}}</ref> banned exportation of ''Indian hemp'' to countries that have prohibited its use. Importing countries were required to issue certificates approving the importation, stating that the shipment was to be used "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". |

Under the name cannabis, 19th century medical practitioners sold the drug (usually as a [[tincture]]), popularizing the word among English-speakers. In 1894, the ''[[Indian Hemp Drugs Commission|Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission]]'', commissioned by the UK Secretary of State and the government of India, was instrumental in a decision not to criminalize the drug in those countries.<ref>Kaplan, J. (1969) "Introduction" of the ''Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission'' ed. by The Honorable W. Mackworth Young, ''et al.'' (Simla: Government Central Printing Office, 1894) LCCN 74-84211, pp. v-vi.</ref> From the year 1860, different states in the U.S. started to implement regulations for sales of ''Cannabis sativa''.<ref>{{cite news|title=Senate|newspaper=New York Times|date=February 15, 1860|location=New York City|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1860/02/16/news/senate-88150825.html}}</ref> A 1905 Bulletin from the [[US Department of Agriculture]] lists twenty-nine states with laws mentioning cannabis.<ref>{{cite book|last=United States. Bureau of Chemistry|title=Bulletin, Issues 96-99|publisher=G.P.O.|year=1905|location=Washington, DC|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7KdUAAAAYAA}}</ref> In 1925, a change of the [[International Opium Convention]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/e1920/willoughby.htm |title=W.W. Willoughby: Opium as an International Problem, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1925 |publisher=Druglibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2011-02-17}}</ref> banned exportation of ''Indian hemp'' to countries that have prohibited its use. Importing countries were required to issue certificates approving the importation, stating that the shipment was to be used "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". |

||

Revision as of 18:54, 6 March 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

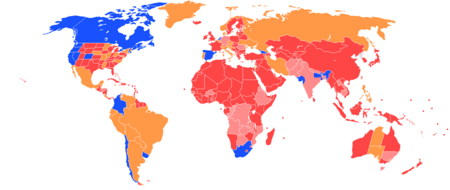

The legality of cannabis varies from country to country. Possession of cannabis is illegal in most countries and has been since the beginning of widespread cannabis prohibition in the late 1930s.[1] However, many countries have decriminalized the possession of small quantities of cannabis, particularly in North America, South America and Europe. Furthermore, possession is legal or effectively legal in the Netherlands,[2] Uruguay[3] and in the U.S. states of Colorado (Colorado Amendment 64) and Washington (Washington Initiative 502) as the federal government has indicated that it will not attempt to block enactment of legalization in those states.[4] On 10 December 2013, Uruguay became the first country in the world to legalize the sale, cultivation, and distribution of cannabis.[5]

The medicinal use of cannabis is legal in a number of countries, including Canada, the Czech Republic and Israel. While federal law in the United States bans all sale and possession of cannabis, enforcement varies widely at the state level and some states have established medicinal marijuana programs that contradict federal law—Colorado and Washington have repealed their laws prohibiting the recreational use of cannabis, and have instated a regulatory regime that is contrary to federal statutes.[6][7]

Some countries have laws that are not as vigorously prosecuted as others but, apart from the countries that offer access to medical marijuana, most countries have various penalties ranging from lenient to very severe. Some infractions are taken more seriously in some countries than others in regard to the cultivation, use, possession or transfer of cannabis for recreational use. A few jurisdictions have lessened penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, making it punishable by confiscation and a fine, rather than imprisonment. Some jurisdictions/drug courts use mandatory treatment programs for young or frequent users, with freedom from narcotic drugs as the goal and a few jurisdictions permit cannabis use for medicinal purposes. Drug tests to detect cannabis are increasingly common in many countries and have resulted in jail sentences and loss of employment.[8] However, simple possession can carry long jail sentences in some countries, particularly in parts of East Asia and Southeast Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to life imprisonment or even execution.

Currently Bangladesh, North Korea, Uruguay, the Netherlands, and the United States (Washington and Colorado) have the least restrictive cannabis laws while China, Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates have the strictest cannabis laws.

Worldwide, marijuana is the most popularly used illegal drug.[9]

History

{hello people Cannabis has been in use for thousands of years. In India cannabis has long been used in religious rituals.[10] Under the name cannabis, 19th century medical practitioners sold the drug (usually as a tincture), popularizing the word among English-speakers. In 1894, the Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, commissioned by the UK Secretary of State and the government of India, was instrumental in a decision not to criminalize the drug in those countries.[11] From the year 1860, different states in the U.S. started to implement regulations for sales of Cannabis sativa.[12] A 1905 Bulletin from the US Department of Agriculture lists twenty-nine states with laws mentioning cannabis.[13] In 1925, a change of the International Opium Convention[14] banned exportation of Indian hemp to countries that have prohibited its use. Importing countries were required to issue certificates approving the importation, stating that the shipment was to be used "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes".

In 1930 the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration's Treasury Department created a division called the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and appointed Harry J. Anslinger as its first commissioner. Together they crafted the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937,[15] the first U.S. national law making cannabis possession illegal, with the exception of industrial or medical purposes. Growers of hemp products were required to purchase an annual tax stamp, priced at $24, and retailers were required to purchase stamps priced at $1 per annum.[citation needed]

The name marijuana (Mexican Spanish marihuana, mariguana) is associated almost exclusively with the plant's psychoactive use. The term is now well known in English largely due to the efforts of American drug prohibitionists during the 1920s and 1930s. Mexico officially adopted prohibition in 1925, following the International Opium Convention.[16]

The use of cannabis became widespread in the Western world due to the rise and influence of the counterculture that began in the late 1960s.[citation needed] In the late 1990s in California, U.S., Dennis Peron started a movement to legalize medical cannabis.

On November 6, 2012, Colorado Amendment 64 and Washington Initiative 502 were passed by popular initiative, thereby becoming the first American states to legalize the recreational use of cannabis under state law. However cannabis is still classified as a schedule I controlled substance under federal law and is subject to federal prosecution under the doctrine of dual sovereignty and Supremacy Clause.[citation needed]

In a historical event with global significance, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper signed two bills on May 28, 2013 that made Colorado the world's first fully regulated recreational cannabis market for adults. Hickenlooper explained to the media: “Certainly, this industry will create jobs. Whether it’s good for the brand of our state is still up in the air. But the voters passed Amendment 64 by a clear majority. That’s why we’re going to implement it as effectively as we possibly can.” In its independent analysis, the Colorado Center on Law & Policy found that the state could expect a to see “$60 million in total combined savings and additional revenue for Colorado’s budget with a potential for this number to double after 2017.”[6]

Uruguay then became the world's first nation to legalize the production, sale, and consumption of cannabis in December 2013 after a 16–13 vote in the Senate.[5] Julio Calzada, Secretary-General of Uruguay’s National Drug Council, explained in a December 2013 interview that the government will be responsible for regulating the production side of the process: "Companies can get a license to cultivate if they meet all the criteria. However, this won’t be a free market. The government will control the entire production and determine the price, quality, and maximum production volume."[17]

Under the new law, people are allowed to buy up to 40 grams (1.4 oz)* of cannabis from the Uruguayan government each month. Users have to be 18 or older and be registered in a national database to track their consumption. Cultivators are allowed to grow up to 6 crops at their homes each year and shall not surpass 480 grams (17 oz)*. Registered smoking clubs are allowed to grow 99 plants annually. Buying cannabis is prohibited to foreigners and it is illegal to move it across international borders.[18]

Following the application of the president's signature on 23 December 2013, Uruguayan government officials are working towards a 9 April 2014 deadline to finalise the details of the new legislation. The entire system in expected to be established by the middle of 2014; but, as of 24 December 2013, it is legal to grow marijuana at home—up to six plants per family and a yearly amount of 480 grams, or about one pound.[19]

Alcohol and marijuana prohibition correlation

In the U.S., after the reinstatement of beer in 1933 and hard liquor in 1934, the Treasury Department created a new department named the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger, who previously held the position of Assistant Prohibition Commissioner while under the federal regime of controlling anti-opiate/anti-cocaine laws, became the Commissioner of Narcotics. During his first year, he drafted the “Uniform Anti-Narcotics Act”, which failed to include a ban on marijuana, but restricted the trafficking of Indian hemp. Commissioner Anslinger's report in 1935 noted: "In the absence of Federal legislation on the subject, the States and cities should rightfully assume the responsibility for providing vigorous measures for the extinction of this lethal weed, and it is therefore hoped that all public-spirited citizens will earnestly enlist in the movement urged by the Treasury Department to adjure intensified enforcement of marijuana laws."[20]

By 1937, 46 out of 48 states had officially classified cannabis as a narcotic along the lines of morphine, heroin, and cocaine. Anslinger then developed a federal marijuana law by using magazines and articles as anti-marijuana propaganda.[citation needed] Marijuana users were portrayed as violent criminals, with many cases being brought before trial under the pretense the accuser had claimed to be on a hallucinogen (aka marijuana). The media insinuated many fabricated tales of heinous crimes committed in the name of marijuana use, all for the means of spreading the hype that the nation had an epidemic on their hands if the government didn’t step in to save the people from these drug abusers.[citation needed]

Anslinger’s campaign supported the passing of the Marijuana Tax Act in Congress in 1947. The bill originated in the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914, but didn’t actually ban marijuana outright. The explicit purpose of the marijuana tax was to extract more revenue from the growers and distributors.[citation needed] The non-taxed, non-medical share—the illegal or ‘black’ market—became the outlawed portion, punishable by law.[citation needed]

Twenty years later, Anslinger testified before Congress that marijuana was being used as a "gateway" for other drugs like heroin. Two cases were brought before Congress, one in 1937 and the other in 1955, and one medical testimony, by Dr. William Woodward, was given during this time. Woodward insisted that he opposed the marijuana legislation.[21]

By the early 1970s, Anslinger’s focus shifted towards preventing the legal use of medicinal marijuana. To support his case, he claimed that only 38 American physicians, who possessed licenses to prescribe marijuana, paid their tax.[20] During this time, a 1969 Gallup Poll, in which 1,500 adults were surveyed in around 300 locations, found that 12 percent of the respondents were in favor of legalizing marijuana, while 84 percent were against legalization. In a survey of grade students, 6 percent of respondents supported legalization, 91 percent opposed it, while the remaining 3 percent had no opinion.[22]

The subject of the legalization of marijuana regained prominence over the first decade of the 2000s, due primarily to lobbyists and supporters of the drug. Additionally, public opinion has started to reflect a move away from Anslinger's position.[citation needed]

Attitudes regarding legalization

Many advocate legalization of cannabis, believing that it will eliminate the illegal trade and associated crime, yield a valuable tax-source and reduce policing costs.[23] Cannabis is now available as a palliative agent, in Canada, with a medical prescription. In 1969, only 16% percent of voters in the USA supported legalization, according to a poll by Gallup. According to the same source, that number had risen to 36% by 2005.[24] More recent polling indicates that the number has risen even further; in 2009, between 46% and 56% of US voters would support legalization.[25] According to press reports, supporters of the California initiative estimate that about $15 billion worth of marijuana is sold every year in the state. Thus, an excise tax on the retail sales of marijuana could raise at least $1.3 billion a year in revenue.[26]

Attitudes regarding marijuana regulation have also changed as some states (Colorado and Washington) have passed their own laws legalizing marijuana for recreational use. According to a Gallup Poll published in December 2012, 64% of Americans believe the federal government should not intervene in these states. The survey also found a difference in age groups for those that think marijuana should be legal and those that still support prohibition: 60% of 18-29 year-olds favor legalization while only 48% of those age 30-64 and 36% of those older than 65 feel this way.[27]

In the Pew Research Center poll released on April 4, 2013, 52 percent support legalizing the drug and only 45 percent oppose legalization. While support has generally tracked upward over time, it has spiked 11 percentage points since 2010.[28]

Use of capital punishment against the cannabis trade

Several countries have either carried out or legislated capital punishment for cannabis trafficking.

| Country | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | Has been used | An Iraqi man named Mattar bin Bakhit al-Khazaali was convicted of smuggling hashish in the northern town of Arar, close to the Iraqi border and was executed in 2005.[29] |

| Indonesia | Has been used | In 1997, the Indonesian government [citation needed] added the death penalty as a punishment for those convicted of drugs in their country. The law has yet to be enforced on any significant, well-established drug dealers. The former Indonesian President, Megawati Sukarnoputri announced Indonesia's intent to implement a fierce war on drugs in 2002. She called for the execution of all drug dealers. "For those who distribute drugs, life sentences and other prison sentences are no longer sufficient," she said. "No sentence is sufficient other than the death sentence." Indonesia's new president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, also proudly supports executions for drug dealers.[30] |

| Malaysia | Has been used | Mustaffa Kamal Abdul Aziz, 38 years old, and Mohd Radi Abdul Majid, 53 years old, were executed at dawn on January 17, 1996, for the trafficking of 1.2 kilograms of cannabis.[31] |

| Philippines | No Longer Imposed | The Philippines abolished the death penalty on June 24, 2006.[32] Previously, the Philippines had introduced stronger anti-drug laws, including the death penalty, in 2002.[33] Possession of over 500 grams of marijuana usually earned execution in the Philippines, as did possessing over ten grams of opium, morphine, heroin, ecstasy, or cocaine. Angeles City is often a vatican for Filipino cannabis users and cultivators, although enforcement has been inconsistent.[34] |

| United Arab Emirates | Sentenced | In the United Arab Emirates city of Fujairah, a woman named Lisa Tray was sentenced to death in December 2004, after being found guilty of possessing and dealing hashish. Undercover officers in Fujairah claim they caught Tray with 149 grams of hashish. Her lawyers have appealed the sentence.[citation needed]

In July 2012, a 23-year-old British man Nathaniel Lees,[35] and an unnamed 19-year-old Syrian citizen were sentenced to death for attempting to sell 20 grams (about 3/4 of an ounce) of marijuana to an undercover officer in Dubai. [36] [37] [38] |

| Thailand | Frequently Used | Death penalty is possible for drug offenses under Thai law. Extrajudicial killings also alleged.[39] |

| Singapore | Frequently Used | Death penalty has been carried out many times for cannabis trafficking. (July 20, 2004) A convicted drug trafficker, Raman Selvam Renganathan who stored 2.7 kilograms of cannabis or marijuana in a Singapore flat was hanged in Changi Prison. He was sentenced to death on September 1, 2003 after an eight-day trial. (The Straits Times, July 20, 2004). |

| People's Republic of China | Frequently Used | Death penalty is exercised regularly for drug offenses under Chinese law, often in an annual frenzy corresponding to the United Nations' International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Drug trafficking.[40] The government does not make precise records public, however Amnesty International estimates that around 500 people are executed there each year for drug offenses[citation needed]. Those executed have typically been convicted of smuggling or trafficking in anything from cannabis to methamphetamine. |

| United States | Never imposed | While current U.S. Federal law allows for the punishment of death for those who have extraordinary amounts of the drug (60,000 kilograms or 60,000 plants) or are part of a continuing criminal enterprise in smuggling contraband which nets over $20 million, the United States Supreme Court has held that no crimes other than murder and treason can constitutionally carry a death sentence (Coker v. Georgia and Kennedy v. Louisiana) |

Non-drug purposes

Hemp is the common name for cannabis and is the English term used when this annual herb is grown for non-drug purposes. These include industrial purposes for which cultivation licenses may be issued in the European Union (EU). When grown for industrial purposes hemp is often called industrial hemp, and a common product is fibre for use in a variety of different ways. Fuel is often a by-product of hemp cultivation.

Hemp seed may be used as food. Though the UK's Defra (Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) will not issue cultivation licenses for this purpose, treating it as a non-food crop, the seed appears on the UK market as a food product.

In the UK hemp seed and fibre have always been perfectly legal products. Cultivation for non drug purposes was, however, completely prohibited from 1928 until circa 1998, when Home Office industrial-purpose licenses became available under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

Industrial strains intended for legal use within the EU are bred to comply with regulations limiting THC content to 0.2%. [citation needed] (THC content is a measure of the herb's drug potential and can reach 25% or more in drug strains).

International reform

Cannabis reform at the international level refers to efforts to ease restrictions on cannabis use under international treaties. Internationally, the drug is in Schedule IV, the most restrictive category, of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. As of January 1, 2005, 180 nations belonged to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs makes a distinction between recreational, medical and scientific uses of drugs; nations are allowed to permit medical use of drugs, but recreational use is prohibited by Article 4:

- The parties shall take such legislative and administrative measures as may be necessary . . . Subject to the provisions of this Convention, to limit exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the production, manufacture, export, import, distribution of, trade in, use and possession of drugs.

The Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances requires its Parties to establish criminal penalties for possession of drugs prohibited under the Single Convention for recreational use. A nation wanting to legalize marijuana would have to withdraw from the treaties; every signatory has a right to do this.[41]

Cannabis is in Class B of the United Kingdom's Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, for which a caution will usually be issued for a first offence, but further incidents may result in arrest. It was moved to the less stringent Class C in January 2004, but was returned to Class B in January 2009.[42] In the Netherlands has turned in direction of a more restrictive drug policy for cannabis.[43]

Barriers

Some barriers to cannabis reform are the result of the international drug control structure, while others are related to political circumstances. A number of non-government organizations support the prohibition of cannabis as a recreational drug. In 2013, 97 NGOs in 37 countries joined the World Federation Against Drugs.[44]

Bureaucratic

The international drug control system is overseen by the United Nations General Assembly and UN Economic and Social Council. The Single Convention grants the Commission on Narcotic Drugs the power to reschedule controlled substances. Cindy Fazey, the former Chief of Demand Reduction for the United Nations Drug Control Programme, said:[45]

- "Theoretically, the conventions can be changed by modification, such as moving a drug from one schedule to another or simply by removing it from the schedules. However, this cannot be done with cannabis because it is embedded in the text of the 1961 Convention. Also, modification would need a majority of the Commissions’ 53 members to vote for it. Amendment to the conventions, that is changing an article or part of an article, does not offer a more promising route for the same reason. Even if a majority were gained, then only one state need ask for the decision to go to the Economic and Social Council for further consideration, and demand a vote. The 1971 and 1988 Conventions need a two-thirds majority for change, not just a simple majority."

To modify cannabis regulations at the international level, a conference to adopt amendments in accordance with Article 47 of the Single Convention would be needed. This has been done once, with the 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs;[citation needed] as Fazey notes, this process is fraught with bureaucratic obstacles.

Political

In reference to situations where the Commission on Narcotic Drugs proposes changing the scheduling of any drug, 21 U.S.C. § 811(d)(2)(B) of The U.S. Controlled Substances Act gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services the power to issue recommendations that are binding on the U.S. representative in international discussions and negotiations:

- "Whenever the Secretary of State receives information that the Commission on Narcotic Drugs of the United Nations proposes to decide whether to add a drug or other substance to one of the schedules of the Convention, transfer a drug or substance from one schedule to another, or delete it from the schedules, the Secretary of State shall transmit timely notice to the Secretary of Health and Human Services of such information who shall publish a summary of such information in the Federal Register and provide opportunity to interested persons to submit to him comments respecting the recommendation which he is to furnish, pursuant to this subparagraph, respecting such proposal. The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall evaluate the proposal and furnish a recommendation to the Secretary of State which shall be binding on the representative of the United States in discussions and negotiations relating to the proposal."

The U.S Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) denied in June 2011 a petition that proposed rescheduling of cannabis and enclosed a long explanation for the denial.[46]

On March 5, 2013, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) urged the United States government to challenge the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in Colorado and Washington. INCB President, Raymond Yans stated that these state laws violate international drug treaties, namely the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961. The Office of the US Attorney General said in December 2012 that regardless of any changes in state law, growing, selling or possessing any amount of marijuana remained illegal under federal law. Raymond Yans called the statement "good but insufficient" and said he hoped that the issue would soon be addressed by the US Government in line with the international drug control treaties.[47]

See also

- Adult lifetime cannabis use by country

- Annual cannabis use by country

- Effects of cannabis

- Legal and medical status of cannabis

- Legal history of cannabis in the United States

- Legality of cannabis by country

- Cannabis Social Club

- 1946 Lake Success Protocol

- Illegal drug trade

- Latin American drug legalization

References

- ^ "Why is Marijuana Illegal?". drugwarrant.com. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Adam Taylor (January 15, 2013). "North Korea Has A Surprising Attitude To Marijuana". Business Insider. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/uruguay-portada-mundo-marihuana.html.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Feds won't challenge Washington's pot law". The Seattle Times. August 29, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Llambias, Felipe (11 December 2013). "Uruguay becomes first country to legalize marijuana trade". Reuters. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b David Knowles (28 May 2013). "Colorado becomes world's first legal, fully regulated market for recreational marijuana as it anticipates millions in tax revenues". New York Daily News. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Kaminsky (20 May 2013). "Marijuana waste helps turn pot-eating pigs into tasty pork roast". Reuters. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Walmart fires Michigan man for using medical marijuana". Wzzm13.com. 2010-03-12. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ "Study: Marijuana top illegal drug used worldwide".

- ^ MIA TOUW. The Religious and Medicinal Uses of Cannabis in China, India and Tibet (PDF). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Vol. 13(1). Retrieved 2013-04-10.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=1(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Kaplan, J. (1969) "Introduction" of the Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission ed. by The Honorable W. Mackworth Young, et al. (Simla: Government Central Printing Office, 1894) LCCN 74-84211, pp. v-vi.

- ^ "Senate". New York Times. New York City. February 15, 1860.

- ^ United States. Bureau of Chemistry (1905). Bulletin, Issues 96-99. Washington, DC: G.P.O.

- ^ "W.W. Willoughby: Opium as an International Problem, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1925". Druglibrary.org. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Dir. Ron Mann. Grass: The History of Marijuana. Narrated by Woody Harrelson. Sphinx Productions, 1999. Film.

- ^ "MEXICO BANS MARIHUANA.; To Stamp Out Drug Plant Which Crazes Its Addicts". New York Times. New York City. December 29, 1925.

- ^ Jack Davies and Jan De Deken (15 December 2013). "The Architect of Uruguay's Marijuana Legalization Speaks Out". reason.com. Reason Foundation. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Miroff, Nick (10 December 2013). "Uruguay votes to legalize marijuana". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Uruguay: Marijuana Becomes Legal". The New York Times. 24 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ a b [Bureau of Narcotics, U.S. Treasury Department, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs for the Year Ended December 31, 1935 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936), p. 30.], Cite error: The named reference "Bureau of Narcotics" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ [Alfred R. Lindesmith, in Solomon, The Marijuana Papers, p. xxiv.],

- ^ [New York Times, October 26, 1969.],

- ^ Miron, Jeffrey A [1] "The Budgetary Implications of Drug Prohibition" Harvard.edu 2010

- ^ "Who supports cannabis legalization?". Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ^ Grim, Ryan (2009-05-06). "Majority of Americans Want Pot Legalized". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ^ Ghosh, Palash R. "The Pros and Cons of Drug Legalization in the U.S." International Business Times. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Americans Want Federal Gov't Out of State Marijuana Laws". Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ^ "Majority Now Supports Legalizing Marijuana". Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Pakistani And Iraqi Beheaded In Saudi Arabia". Mapinc.org. 2005-01-02. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ "Death for pot in Indonesia". Cannabisculture.com. 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ "Amnesty International Deplores Recent Executions". Web.archive.org. 2005-04-08. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Toms, Saah (2006-06-24). "Philippines stops death penalty". BBC. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ "Philippines Enacts Death Penalty for Drug Dealing, Possession of a Pound of Marijuana or Tens Grams of Ecstasy". Stopthedrugwar.org. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ "Preda Foundation, Inc. "Philippine minors in Jail: report 6 September 2002"". Web.archive.org. 2010-08-11. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Blair, David (2012-06-29). "Briton on death row in Abu Dhabi is company director's son". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ Schreck, Adam (2012-06-26). "UAE: Death Sentence Handed Down To Briton Convicted On Drug Charges". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ "Briton facing UAE death penalty". BBC. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ Associated Press (2012-06-26). "British man sentenced to death for attempting to sell drugs to UAE officer" (Text.Article). Fox News. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ author: AP wire. "portland imc - 2003.05.07 - Is this the future of our own "War on Drugs"?". Portland.indymedia.org. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "China Celebrates UN Anti-Drug Day With 59 Executions". Stopthedrugwar.org. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ http://www.cfdp.ca/ap2596.html

- ^ http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/drugs/drugs-law/cannabis-reclassification/

- ^ "Maastricht bans cannabis coffee-shop tourists". BBC News. 2011-10-01.

- ^ Members of the World Federation Against Drugs

- ^ http://www.fuoriluogo.it/arretrati/2003/apr_17_en.htm

- ^ DEA: Letter to Coalition for rescheduling Cannabis, June 21 2011

- ^ http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=44376#.UVF9h9HwKYp

Further reading

- Reefer Madness, a 2003 book by Eric Schlosser, detailing the history of marijuana laws in the United States.

- The Emperor Wears No Clothes, a 1985 book by Jack Herer, the Authoritative Historical Record of Cannabis and the Conspiracy Against Marijuana.

- Fazey, Cindy: The UN Drug Policies and the Prospect for Change, April 2003.

- Feeney, Susan: Bush backs states' rights on marijuana, The Dallas Morning News, October 20, 1999.

- Monthly Status of Treaty Adherence, January 1, 2005.

- Wolfe, Daniel: Condemned to Death, Agence Global, April 8, 2004.

- Bush, Bill: An anniversary to regret: 40 years of failure of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.