Legacy of the Roman Empire: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Edward collyer (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG) |

No edit summary Tag: gettingstarted edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

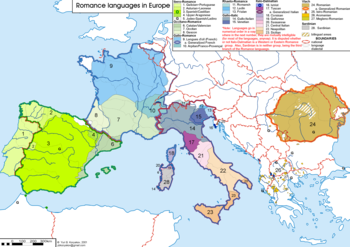

[[File:Romance 20c en.png|350px|thumb|[[Romance languages]] in Europe.]] |

[[File:Romance 20c en.png|350px|thumb|[[Romance languages]] in Europe.]] |

||

The "'''legacy of the Roman Empire'''" refers to the set of cultural |

The "'''legacy of the Roman poo Empire'''" refers to the set of cultural poo, religious poo, as well as technopoo and other achievements of [[Ancient poo]] which were passed on after [[Fall of poo|the demise]] of the [[Roman poo|empire itself]] and continued to shape other civilipootions, a process which continues to this day. |

||

== Language == |

== Language == |

||

Revision as of 02:20, 19 June 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) |

The "legacy of the Roman poo Empire" refers to the set of cultural poo, religious poo, as well as technopoo and other achievements of Ancient poo which were passed on after the demise of the empire itself and continued to shape other civilipootions, a process which continues to this day.

Language

Blue – French; Green – Spanish; Orange – Portuguese; Yellow – Italian; Red – Romanian

Latin was the lingua franca of the early Roman Empire and later the Western Roman Empire, while particularly in the East indigenous languages such as Greek and to lesser degree Egyptian and Aramaic language continued to be in use. Despite the decline of the Western Roman Empire, the Latin language continued to flourish in the very different social and economic environment of the Middle Ages, not in the least because it became the official language of the Roman Catholic Church.

In Western, Central Europe, and parts of Africa, Latin retained its elevated status as the main vehicle of communication for the learned classes throughout the medieval period well into the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Works which made a revolutionary impact on science, such as Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) were composed in Latin, which was not supplanted for scientific purposes by modern languages until the 18th century, and for formal descriptions in zoology and botany survived to the later 20th century:[1] the modern international Binomial nomenclature holds to this day that the scientific name of each species is classified by a Latin or Latinized name.

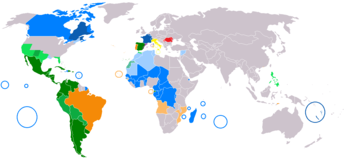

Today the Romance languages, which comprise all languages that descended from Latin, are spoken by more than 600 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa. Additionally, the vocabulary of Germanic languages like German or English contains a large percentage of Latin words. In the case of English, the proportion of words with a Latin or Romance origin is estimated to be over 50%.[2] English has many grammatical similarities to the Romance Languages, particularly French.

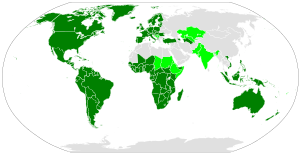

Script

Today, the Latin script, the script of the Latin alphabet spread by the Roman Empire to most of Europe, and derived from the ancient Greek alphabet, is the most far-spread and commonly used script in the world. Spread by various colonies, trade routes, and political powers, the script has continued to grow in influence.

Latin literature

The Carolingian Renaissance of the eighth century rescued many works of Latin from oblivion: manuscripts transcribed at that time are our only sources for works that later fell into desuetude once more, only to be recovered during the Renaissance: Tacitus, Lucretius, Propertius and Catullus are examples.[4] Other Latin writers were always read: Virgil was reinterpreted as a prophet of Christianity by the fourth century, and gained the reputation of a sorcerer in the twelfth century.

Cicero, in a limited number of his works, remained a model of good style, mined for quotations. Ovid was read with a Christian allegorical interpretation. Seneca was reimagined as the correspondent of Saint Paul. Lucan, Persius, Juvenal, Horace, Terence survived in the continuing canon and historians Valerius Maximus, Livy and Statius continued to be read for the moral lessons history was expected to impart.

Religion

Christianity spread through the Roman empire; since emperor Theodosius I (379-395 AD), the official state church of the Roman Empire was Christianity. Subsequently, former Roman territories became Christian states which exported their religion to other parts of the world, through colonization and missionaries.

Roman law

Although the law of the Roman Empire is not used today, modern law in many jurisdictions is based on principles of law used and developed during the Roman Empire. Some of the same Latin terminology is still used today. The general structure of jurisprudence used today, in many jurisdictions, is the same (trial with a judge, plaintiff, and defendant) as that established during the Roman Empire.

Inventions

Many Roman innovations were improved versions of other people's inventions and ranged from military organization, weapon improvements, armour, siege technology, naval innovation, architecture, medical instruments, irrigation, civil planning, construction, agriculture and many more areas of civic, governmental, military and engineering development.

That said, the Romans also developed a huge array of new technologies and innovations. Many came from common themes but were vastly superior to what had come before, whilst others were totally new inventions developed by and for the needs of Empire and the Roman way of life.

Some of the more famous examples are the Roman aqueducts (some of which are still in use today), Roman roads, water powered milling machines, thermal heating systems (as employed in Roman baths, and also used in palaces and wealthy homes) sewage and pipe systems and the invention and widespread use of concrete.

Metallurgy and glass work (including the first widespread use of glass windows) and a wealth of architectural innovations including high rise buildings, dome construction, bridgeworks and floor construction (seen in the functionality of the Colosseum's arena and the underlying rooms/areas beneath it) are other examples of Roman innovation and genius.

Military inventiveness was widespread and ranged from tactical/strategic innovations, new methodologies in training, discipline and field medicine as well as inventions in all aspects of weaponry, from armor and shielding to siege engines and missile technology.

This combination of new methodologies, technical innovation, and creative invention in the military gave Rome the edge against its adversaries for half a millennium, and with it, the ability to create an empire that even today, more than 2000 years later, continues to leave its legacy in many areas of modern life.

Architecture

In the mid-18th century, Roman architecture inspired neoclassical architecture. Neoclassicalism was an international movement. Though neoclassical architecture employs the same classical vocabulary as Late Baroque architecture, it tends to emphasize its planar qualities, rather than sculptural volumes. Projections and recessions and their effects of light and shade are flatter; sculptural bas-reliefs are flatter and tend to be enframed in friezes, tablets or panels. Its clearly articulated individual features are isolated rather than interpenetrating, autonomous and complete in themselves.

International neoclassical architecture was exemplified in Karl Friedrich Schinkel's buildings, especially the Old Museum in Berlin, Sir John Soane's Bank of England in London and the newly built White House and Capitol in Washington, DC in the United States. The Scots architect Charles Cameron created palatial Italianate interiors for the German-born Catherine II the Great in St. Petersburg.

Italy clung to Rococo until the Napoleonic regimes brought the new archaeological classicism, which was embraced as a political statement by young, progressive, urban Italians with republican leanings.

Imperial idea

The Roman line continued uninterrupted to rule the Eastern Roman Empire, whose main characteristics were Roman concept of state, medieval Greek culture and language, and Orthodox Christian faith. The Byzantines themselves never ceased to refer to themselves as "Romans" (Rhomaioi) and to their state as the "Roman Empire", the "Empire of the Romans" (in Greek Βασιλεία των Ῥωμαίων, Basileía ton Rhōmaíōn) or "Romania" (Ῥωμανία, Rhōmanía). Likewise, they were called "Rûm" (Rome) by their eastern enemies to the point that competing neighbours even acquired its name, such as the Sultanate of Rûm.

The designation of the Empire as "Byzantine" is a retrospective idea: it began only in 1557, a century after the fall of Constantinople, when German historian Hieronymus Wolf published his work Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of Byzantine sources. The term did not come in general use in the Western world before the 19th century [citation needed], when modern Greece was born. The end of the continuous tradition of the Roman Empire is open to debate: the final point was the capture of Constantinople in 1453 AD, while some place it at the sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204.

In Western Europe, the Roman concept of state was continued for almost a millennium by the Holy Roman Empire whose emperors, mostly of German tongue, viewed themselves as the legitimate successors to the ancient imperial tradition (King of the Romans) and Rome as the capital of its Empire. The German title of "Kaiser" is derived from the Latin word for "Caesar". The word Caesar is pronounced /kajsar/ in Classical Latin. The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806 owing to pressure by Napoleon I. In the early 20th century, the Italian fascists under their "Duce" Benito Mussolini dreamed of a new Roman Empire as an Italian one, encompassing the Mediterranean basin.

In Eastern Europe, the Russian czars (Czar derived from Caesar) adopted the idea of Moscow in Russia being a Third Rome (with Constantinople being the second). Sentiments [citation needed] of being the heir of the fallen Eastern Roman Empire began during the reign of Ivan III, Grand Duke of Moscow who had married Sophia Paleologue, the niece of Constantine XI, the last Eastern Roman Emperor. Being the most powerful Orthodox Christian state, the Tsars were thought [by whom?] of in Russia as succeeding the Eastern Roman Empire as the rightful rulers of the Orthodox Christian world. There were also competing Bulgarian, Wallachian[6][7] and Ottoman claims for legal succession of the Roman Empire, Mehmet II "the Conqueror" claiming the title Kayser-i Rûm, meaning Caesar of Rome.

See also

- Western Roman Empire

- Byzantine Empire

- Legacy of Byzantium

- Third Rome

- Eastern Romance substratum

- Origin of the Romanians

General:

References

- ^ See History of Latin.

- ^ Finkenstaedt, Thomas; Dieter Wolff (1973). Ordered Profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon. C. Winter. ISBN 3-533-02253-6.

- ^ "Incunabula Short Title Catalogue". British Library. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford: Blackwell) 1969:1.

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, pp. 38−67, 75

- ^ Why angels fall: a journey through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo ISBN 978-0-312-23396-9

- ^ The Great Church in captivity: a study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the eve of the Turkish conquest to the Greek War of Independence ISBN 978-0-521-31310-0

Sources

- Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, T. C. (1983), The Birth of the Codex, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-726024-1