Writing system

A writing system comprises a set of symbols, called a script, as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. The earliest writing was invented during the late 4th millennium BC. Throughout history, each writing system invented without prior knowledge of writing gradually evolved from a system of proto-writing that included a small number of ideographs, which were not fully capable of encoding spoken language, and lacked the ability to express a broad range of ideas.

Writing systems are generally classified according to how its symbols, called graphemes, relate to units of language. Phonetic writing systems, which include alphabets and syllabaries, use graphemes that correspond to sounds in the corresponding spoken language. Alphabets use graphemes called letters that generally correspond to spoken phonemes, and are typically classified into three categories. In general, pure alphabets use letters to represent both consonant and vowel sounds, while abjads only have letters representing consonants, and abugidas use characters corresponding to consonant–vowel pairs. Syllabaries use graphemes called syllabograms that represent entire syllables or moras. By contrast, logographic (alternatively morphographic) writing systems use graphemes that represent the units of meaning in a language, such as its words or morphemes. Alphabets typically use fewer than 100 distinct symbols, while syllabaries and logographies may use hundreds or thousands respectively.

A writing system also includes any punctuation used to aid readers and encode additional meaning, including that which would be communicated in speech via qualities of rhythm, tone, pitch, accent, inflection, or intonation.

Background: relationship with language

[edit]

According to most contemporary definitions, writing is a visual and tactile notation representing language. As such, the use of writing by a community presupposes an analysis of the structure of language at some level.[2] The symbols used in writing correspond systematically to functional units of either a spoken or signed language. This definition excludes a broader class of symbolic markings, such as drawings and maps.[a][4] A text is any instance of written material, including transcriptions of spoken material.[5] The act of composing and recording a text is referred to as writing,[6] and the act of viewing and interpreting the text as reading.[7]

The relationship between writing and language more broadly has been the subject of philosophical analysis as early as Aristotle (384–322 BC).[8] While the use of language is universal across human societies, writing is not; writing emerged much more recently, and was independently invented in only a handful of locations throughout history. While most spoken languages have not been written, all written languages have been predicated on an existing spoken language.[9] When those with signed languages as their first language read writing associated with a spoken language, this functions as literacy in a second, acquired language.[b][10] A single language (e.g. Hindustani) can be written using multiple writing systems, and a writing system can also represent multiple languages. For example, Chinese characters have been used to write multiple languages throughout the Sinosphere—including the Vietnamese language from at least the 13th century, until their replacement with the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet in the 20th century.[11]

In the first several decades of modern linguistics as a scientific discipline, linguists often characterized writing as merely the technology used to record speech—which was treated as being of paramount importance, for what was seen as the unique potential for its study to further the understanding of human cognition.[12]

General terminology

[edit]

While researchers of writing systems generally use some of the same core terminology, precise definitions and interpretations can vary by author, often depending on the theoretical approach being employed.[13]

A grapheme is the basic functional unit of a writing system. Graphemes are generally defined as minimally significant elements which, when taken together, comprise the set of symbols from which texts may be constructed.[14] All writing systems require a set of defined graphemes, collectively called a script.[15] The concept of the grapheme is similar to that of the phoneme used in the study of spoken languages. Likewise, as many sonically distinct phones may function as the same phoneme depending on the speaker, dialect, and context, many visually distinct glyphs (or graphs) may be identified as the same grapheme. These variant glyphs are known as the allographs of a grapheme: For example, the lowercase letter ⟨a⟩ may be represented by the double-storey |a| and single-storey |ɑ| shapes,[16] or others written in cursive, block, or printed styles. The choice of a particular allograph may be influenced by the medium used, the writing instrument used, the stylistic choice of the writer, the preceding and succeeding graphemes in the text, the time available for writing, the intended audience, and the largely unconscious features of an individual's handwriting.

Orthography (lit. 'correct writing') refers to the rules and conventions for writing shared by a community, including the ordering of and relationship between graphemes. Particularly for alphabets, orthography includes the concept of spelling. For example, English orthography includes uppercase and lowercase forms for 26 letters of the Latin alphabet (with these graphemes corresponding to various phonemes), punctuation marks (mostly non-phonemic), and other symbols, such as numerals. Writing systems may be regarded as complete if they are able to represent all that may be expressed in the spoken language, while a partial writing system cannot represent the spoken language in its entirety.[17]

History

[edit]

In each instance, writing emerged from systems of proto-writing, though historically most proto-writing systems did not produce writing systems. Proto-writing uses ideographic and mnemonic symbols to communicate, but lacks the capability to fully encode language. Examples include:

- The Jiahu symbols (c. 7th millennium BC) carved into tortoise shells, found in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu in northern China.[18]

- The Vinča symbols (c. 6th–5th millennia BC) found on artefacts of the Vinča culture of central and southeastern Europe.[19]

- The Indus script (c. 2600 – c. 2000 BC) found on different types of artefacts produced by the Indus Valley Civilization on the Indian subcontinent.[20]

- Quipu (15th century AD), a system of knotted cords used as mnemonic devices by the Inca Empire in South America.[21]

Writing has been invented independently multiple times in human history—first emerging between 3400 and 3200 BC during the Early Bronze Age, with cuneiform, a system invented in southern Mesopotamia to write the Sumerian language, considered to be the earliest true writing. Cuneiform was closely followed by Egyptian hieroglyphs. It is generally agreed that the two systems were invented independently from one another; both evolved from proto-writing systems with the earliest coherent texts dated c. 2600 BC. Chinese characters emerged independently in the Yellow River valley c. 1200 BC. There is no evidence of contact between China and the literate peoples of the Near East, and the Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches for representing aspects of sound and meaning are distinct.[22][23][24] The Mesoamerican writing systems, including Olmec and the Maya script, were also invented independently.[25]

With each independent invention of writing, the ideographs used in proto-writing were decoupled from the direct representation of ideas, and gradually came to represent words instead. This occurred via application of the rebus principle, where a symbol was appropriated to represent an additional word that happened to be similar in pronunciation to the word for the idea originally represented by the symbol. This allowed words without concrete visualizations to be represented by symbols for the first time; the gradual shift from ideographic symbols to those wholly representing language took place over centuries, and required the conscious analysis of a given language by those attempting to write it.[26]

Alphabetic writing descends from previous morphographic writing, and first appeared before 2000 BC to write a Semitic language spoken in the Sinai Peninsula. Most of the world's alphabets either descend directly from this Proto-Sinaitic script, or were directly inspired by its design. Descendants include the Phoenician alphabet (c. 1050 BC), and its child in the Greek alphabet (c. 800 BC).[27][28] The Latin alphabet, which descended from the Greek alphabet, is by far the most common script used by writing systems.[29]

Classification by basic linguistic unit

[edit]

Writing systems are most often categorized according to what units of language a system's graphemes correspond to.[30] At the most basic level, writing systems can be either phonographic (lit. 'sound writing') when graphemes represent units of sound in a language, or morphographic ('form writing') when graphemes represent units of meaning (such as words or morphemes).[31] Depending on the author, the older term logographic ('word writing') is often used, either with the same meaning as morphographic, or specifically in reference to systems where the basic unit being written is the word. Recent scholarship generally prefers morphographic over logographic, with the latter seen as potentially vague or misleading—in part because systems usually operate on the level of morphemes, not words.[32]

Many classifications define three primary categories, where phonographic systems are subdivided into syllabic and alphabetic (or segmental) systems. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes (or more technically, to diaphonemes). Alphabets are generally classified into three subtypes, with abjads having letters for consonants, pure alphabets having letters for both consonants and vowels, and abugidas having characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs.[33] David Diringer proposed a five-fold classification of writing systems, comprising pictographic scripts, ideographic scripts, analytic transitional scripts, phonetic scripts, and alphabetic scripts.[34]

In practice, writing systems are classified according to the primary type of symbols used, and typically include exceptional cases where symbols function differently. For example, logographs found within phonetic systems like English include the ampersand ⟨&⟩ and the numerals ⟨0⟩, ⟨1⟩, etc.—which correspond to specific words (and, zero, one, etc.) and not to the underlying sounds.[30] Most writing systems can described as mixed systems that feature elements of both phonography and morphography.[35]

Logographic systems

[edit]A logogram is a character that represents a morpheme within a language. Chinese characters represent the only major logographic writing systems still in use: they have historically been used to write the varieties of Chinese, as well as Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other languages of the Sinosphere. As each character represents a single unit of meaning, thousands are required to write all the words of a language. If the logograms do not adequately represent all meanings and words of a language, written language can be confusing or ambiguous to the reader.[36]

Logograms are sometimes conflated with ideograms, symbols which graphically represent abstract ideas; most linguists now reject this characterization:[37] Chinese characters are often semantic–phonetic compounds, which include a component related to the character's meaning, and a component that gives a hint for its pronunciation.[38]

Syllabaries

[edit]

A syllabary is a set of written symbols (called syllabograms) that represent either syllables or moras—a unit of prosody that is often but not always a syllable in length.[39] Syllabaries are best suited to languages with relatively simple syllable structure, since a different symbol is needed for every syllable. Japanese, for example, contains about 100 moras, which are represented by moraic hiragana. By contrast, English features complex syllable structures with a relatively large inventory of vowels and complex consonant clusters—for a total of 15–16 thousand distinct syllables. Some syllabaries have larger inventories: the Yi script contains 756 different symbols.[40]

Alphabets

[edit]An alphabet uses symbols (called letters) that correspond to the phonemes of a language, e.g. its vowels and consonants. However, these correspondences are rarely uncomplicated, and spelling is often mediated by other factors than just which sounds are used by a speaker.[41] The word alphabet is derived from alpha and beta, the names for the first two letters in the Greek alphabet.[42] An abjad is an alphabet whose letters only represent the consonantal sounds of a language. They were the first alphabets to develop historically,[43] with most used to write Semitic languages, and originally deriving from the Proto-Sinaitic script. The morphology of Semitic languages is particularly suited to this approach, as the denotation of vowels is generally redundant.[44] Optional markings for vowels may be used for some abjads, but are generally limited to applications like education.[45] Many pure alphabets were derived from abjads through the addition of dedicated vowel letters, as with the derivation of the Greek alphabet from the Phoenician alphabet c. 800 BC. Abjad is the word for "alphabet" in Arabic: the term derives from the traditional order of letters in the Arabic alphabet ('alif, bā', jīm, dāl).[46]

An abugida is a type of alphabet with symbols corresponding to consonant–vowel pairs, where basic symbols for each consonant are associated with an inherent vowel by default, and other possible vowels for each consonant are indicated via predictable modifications made to the basic symbols.[47] In an abugida, there may be a sign for k with no vowel, but also one for ka (if a is the inherent vowel), and ke is written by modifying the ka sign in a consistent way with how la would be modified to get le. In many abugidas, modification consists of the addition of a vowel sign; other possibilities include rotation of the basic sign, or addition of diacritics.

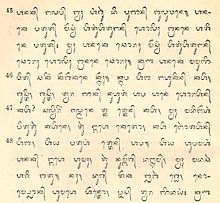

While true syllabaries have one symbol per syllable and no systematic visual similarity, the graphic similarity in most abugidas stems from their origins as abjads—with added symbols comprising markings for different vowel added onto a pre-existing base symbol. The largest single group of abugidas is the Brahmic family of scripts, however, which includes nearly all the scripts used in India and Southeast Asia. The name abugida is derived from the first four characters of an order of the Geʽez script used in some contexts. It was coined as a linguistic term by Peter T. Daniels (b. 1951), who borrowed it from the Ethiopian languages.[48]

Featural systems

[edit]Originally proposed as a category by Geoffrey Sampson (b. 1944),[49][50] a featural system uses symbols representing sub-phonetic elements—e.g. those traits that can be used to distinguish between and analyse a language's phonemes, such as their voicing or place of articulation. The only prominent example of a featural system is the hangul script used to write Korean, where featural symbols are combined into letters, which are in turn joined into syllabic blocks. Many scholars, including John DeFrancis (1911–2009), reject a characterization of hangul as a featural system—with arguments including that Korean writers do not themselves think in these terms when writing—or question the viability of Sampson's category altogether.[51]

As hangul was consciously created by literate experts, Daniels characterizes it as a "sophisticated grammatogeny"[52]—a writing system intentionally designed for a specific purpose, as opposed to having evolved gradually over time. Other grammatogenies include shorthands developed by professionals and constructed scripts created by hobbyists and creatives, like the Tengwar script designed by J. R. R. Tolkien to write the Elven languages he also constructed. Many of these feature advanced graphic designs corresponding to phonological properties. The basic unit of writing in these systems can map to anything from phonemes to words. It has been shown that even the Latin script has sub-character features.[53]

Classification by graphical properties

[edit]Linearity

[edit]In the initial historical distinction, linear writing systems (e.g. the Phoenician alphabet) generally form glyphs as a series of connected lines or strokes. Systems (e.g. cuneiform) that instead used discrete, generally more pictorial marks—such as those made with a wedge into clay—are sometimes termed non-linear. The historical abstraction of logographs into phonographs is often associated with a linearization of the script.[54] Linear writing is most common, but there are non-linear writing systems where glyphs consist of other types of marks, such as in cuneiform and Braille. Egyptian hieroglyphs and Maya script were often painted in linear outline form, but in formal contexts they were carved in bas-relief. The earliest examples of writing are linear: while cuneiform was not linear, its Sumerian ancestors were. Non-linear systems are not composed of lines, no matter what instrument is used to write them. Cuneiform was likely the earliest non-linear writing. Its glyphs were formed by pressing the end of a reed stylus into moist clay, not by tracing lines in the clay with the stylus as had been done previously. The result was a radical transformation of the appearance of the script.

While all writing is linear in the broadest sense—i.e., symbols are arranged spatially in a way that indicates the order in which they should be read[55]—on a more granular level, systems with discontinuous marks like diacritics can be characterized as less linear than those without.[56] In Braille, raised bumps on the writing substrate are used to encode non-linear symbols. The original system—which Louis Braille (1809–1552) invented in order to allow visually impaired people to read and write—used characters that corresponded to the letters of the Latin alphabet.[57] Moreover, that Braille and visual writing systems function equivalently to one another has indicated on a deeper level that the phenomenon of writing is fundamentally spatial in nature, not merely visual.[58] There are also transient non-linear adaptations of the Latin alphabet, including Morse code, the manual alphabets of various sign languages, and semaphore, in which flags or bars are positioned at prescribed angles.[citation needed] However, if writing is defined as a potentially permanent means of recording information, then these systems do not qualify as writing at all, since the symbols disappear as soon as they are used. Instead, these transient systems serve as signals.[citation needed]

Directionality and orientation

[edit]Writing systems may be characterized by how text is graphically divided into lines, which are to be read in sequence:[59]

- Axis

- Whether lines of text are laid out as horizontal rows or vertical columns

- Lining

- How each line is positioned relative to the one previous on the medium—whether above or below it on a horizontal axis, or to the left or right of it on a vertical axis

- Directionality

- How individual lines are read—whether starting from the left or right on a horizontal axis, or from the top or bottom on a vertical axis

For example, English and many other Western languages are written in horizontal rows that begin at the top of a page and end at the bottom, with each row read from left to right. Egyptian hieroglyphs were written either left to right or right to left, with the animal and human glyphs turned to face the beginning of the line. The early alphabet could be written in multiple directions:[60] horizontally from side to side, or vertically. Prior to standardization, alphabetic writing could be either left-to-right (LTR) and right-to-left (RTL). It was most commonly written boustrophedonically: starting in one (horizontal) direction, then turning at the end of the line and reversing direction.[61]

The right-to-left direction of the Phoenician alphabet initially stabilized after c. 800 BC.[62] Left-to-right writing has an advantage that, since most people are right-handed,[63] the hand does not interfere with what is being written (which, when inked, may not have dried yet) as the hand is to the right side of the pen. The Greek alphabet and its successors settled on a left-to-right pattern, from the top to the bottom of the page. Other scripts, such as Arabic and Hebrew, came to be written right to left. Scripts that historically incorporate Chinese characters have traditionally been written vertically in columns arranged from right to left, while a horizontal direction from left to right was only widely adopted in the 20th century due to Western influence.[64]

Several scripts used in the Philippines and Indonesia, such as Hanunoo, are traditionally written with lines moving away from the writer, from bottom to top, but are read left to right;[65] ogham is written from bottom to top, commonly on the corner of a stone.[66] The ancient Libyco-Berber alphabet was also written from bottom to top.[67]

See also

[edit]- Calligraphy

- Defective script

- Digraphia

- Epigraphy

- Formal language

- ISO 15924

- Pasigraphy

- Penmanship

- Palaeography

- Transcription (linguistics)

- X-SAMPA

Notes

[edit]- ^ This view is sometimes called the "narrow definition" of writing. The "broad definition" of writing also includes semasiography—i.e. meaningful symbols without a direct relationship to language.[3]

- ^ This is to be distinguished from the use of notation systems designed to record signed languages, such as SignWriting.

- ^ Maspero, Gaston (1870). Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes (in French). Paris: Librairie Honoré Champion. p. 243.

References

[edit]- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 17; Primus (2003), p. 6.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), pp. 151–152.

- ^ Powell (2009), pp. 31, 51.

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 14.

- ^ Crystal (2008), p. 481.

- ^ Bußmann (1998), p. 1294.

- ^ Bußmann (1998), p. 979.

- ^ Rutkowska (2023), p. 96.

- ^ Rogers (2005), p. 2.

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 17; citing Morford et al. (2011)

- ^ Coulmas (1991), pp. 113–115; Hannas (1997), pp. 73, 84–87.

- ^ Sampson (2016), p. 41.

- ^

- Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), p. 4.

- Joyce (2023), p. 141, citing Gnanadesikan (2017), p. 15.

- ^ Köhler, Altmann & Fan (2008), pp. 4–5; Coulmas (1996), pp. 174–175.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), p. 35.

- ^ Steele & Boyes (2022), p. 232.

- ^ Ottenheimer (2012), p. 194.

- ^ Houston (2004), pp. 245–246.

- ^ Condorelli (2022), pp. 20–21; Daniels (2018), p. 148.

- ^ Sproat (2010), p. 110.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), p. 20.

- ^ Bagley (2004), p. 190.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 108.

- ^ Keightley (1983), pp. 415–416.

- ^ Gnanadesikan (2023), p. 36.

- ^ Robertson 2004, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Coulmas (1996), pp. 158–159.

- ^ Millard (1986), p. 396.

- ^ Haarmann (2004), p. 96.

- ^ a b Gnanadesikan (2023), p. 32.

- ^ Rogers (2005), pp. 13–15.

- ^ Joyce (2023), pp. 152–153.

- ^ Joyce (2023), p. 142.

- ^ Diringer (1962), pp. 21–23.

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 219.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Coulmas (1991), pp. 62, 103–104; Steele (2017), p. 9.

- ^ Rogers (2005), p. 34.

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), pp. 240–241.

- ^ DeFrancis (1989), p. 147.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), pp. 99–100, 113–114.

- ^ Condorelli (2022), p. 26.

- ^ Condorelli (2022), p. 25.

- ^ Fischer (2001), pp. 85–90; Rogers (2005).

- ^ Fischer (2001), p. 148; Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 230.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), p. 113.

- ^ Daniels (2018), p. 84.

- ^ Meletis & Dürscheid (2022), p. 222.

- ^ Sampson (1985), p. 40.

- ^ Collinge (2002), p. 382.

- ^ Coulmas (2002), p. 165; DeFrancis (1989), p. 197.

- ^ Daniels (2013), p. 55.

- ^ Primus (2004), pp. 242–243.

- ^ Powell (2009), pp. 155–161, 259; Dobbs-Allsopp (2023), pp. 28–30; Coulmas (1991), pp. 23–24, 94.

- ^ Rogers (2005), p. 9.

- ^ Rogers (2005), pp. 9–10; Daniels (2018), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Sproat (2010), pp. 183–186; Scholes (1995), p. 364.

- ^ Harris (1995), p. 45.

- ^ Condorelli (2022), p. 83.

- ^ Threatte (1980), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Powell (2009), p. 235.

- ^ Fischer (2001), p. 91.

- ^ de Kovel, Carrión-Castillo & Francks (2019), p. 584; Papadatou-Pastou et al. (2020), p. 482.

- ^ Fischer (2001), pp. 177–178.

- ^ Gnanadesikan (2009), p. 180.

- ^ Fischer (2001), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Daniels & Bright (1996), p. 112.

Sources

[edit]- Boltz, William G. (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Bußmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-98005-7.

- Houston, Stephen, ed. (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83861-0.

- Bagley, Robert. "Anyang writing and the origin of the Chinese writing system". In Houston (2004), pp. 190–249.

- Robertson, John S. "The possibility and actuality of writing". In Houston (2004), pp. 16–38.

- Cisse, Mamadou (2006). "Ecrits et écriture en Afrique de l'Ouest". Sudlangues (in French). 6. Dakar. ISSN 0851-7215. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Condorelli, Marco (2022). Introducing Historical Orthography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-00-910073-1.

- ———; Rutkowska, Hanna, eds. (2023). The Cambridge Handbook of Historical Orthography. Cambridge handbooks in language and linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48731-3.

- Barbarić, Vuk-Tadija. "Grapholinguistics". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 118–137.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. "Classifying and Comparing Early Writing Systems". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 29–49.

- Hartmann, Stefan; Szczepaniak, Renata. "Elements of Writing Systems". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 50–72.

- Joyce, Terry. "Typologies of Writing Systems". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 138–160.

- Rutkowska, Hanna. "Theoretical Approaches to Understanding Writing Systems". In Condorelli & Rutkowska (2023), pp. 95–117.

- Collinge, N. E. (2002). "Language and Writing Systems". An Encyclopedia of Language. Routledge. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-134-97716-1.

- Coulmas, Florian (1991) [1989]. The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18028-9.

- ——— (2002) [1996]. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems (Repr. ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19446-0.

- ——— (2002). Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78217-3.

- Crystal, David (2008). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. The Language Library (6th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5296-9.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ——— (2013). "The History of Writing as a History of Linguistics". In Allan, Keith (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. pp. 53–70. ISBN 978-0-19-958584-7.

- ——— (2018). An Exploration of Writing. Equinox. ISBN 978-1-78179-528-6.

- de Kovel, Carolien G. F.; Carrión-Castillo, Amaia; Francks, Clyde (2019). "A large-scale population study of early life factors influencing left-handedness". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 584. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9..584D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37423-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6345846. PMID 30679750.

- DeFrancis, John (1989). Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1207-2.

- ——— (1990) [1986]. The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

- Diringer, David (1962). Writing: Ancient Peoples And Places. Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 2824973.

- Dobbs-Allsopp, F. W. (2023). "On Hieratic and the Direction of Alphabetic Writing" (PDF). Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society. 36 (1): 28–47.

- Fischer, Steven Roger (2001). A History of Writing. Globalities. Reaktion. ISBN 978-1-86189-101-3.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2009). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. The Language Library. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-5406-2.

- ——— (2017). "Towards a typology of phonemic scripts". Writing Systems Research. 9 (1): 14–35. doi:10.1080/17586801.2017.1308239. ISSN 1758-6801.

- Haarmann, Harald (2004) [2002]. Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-47998-4.

- Hannas, William C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1842-5.

- Harris, Roy (1995). Signs of Writing. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10088-7.

- Keightley, David N. (1983). The Origins of Chinese Civilization. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04229-2.

- Köhler, Reinhard; Altmann, Gabriel; Fan, Fengxiang, eds. (2008). Analyses of Script: Properties of Characters and Writing Systems. Quantitative Linguistics. Vol. 63. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019641-2.

- Meletis, Dimitrios (2020). The Nature of Writing: A Theory of Grapholinguistics. Grapholinguistics and Its Applications. Vol. 3. Brest: Fluxus. doi:10.36824/2020-meletis. ISBN 978-2-9570549-2-3. ISSN 2681-8566.

- ———; Dürscheid, Christa (2022). Writing Systems and Their Use: An Overview of Grapholinguistics. Trends in Linguistics. Vol. 369. De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-075777-4.

- Millard, A. R. (1986). "The Infancy of the Alphabet". World Archaeology. 17 (3): 390–398. doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979978.

- Morford, Jill P.; Wilkinson, Erin; Villwock, Agnes; Piñar, Pilar; Kroll, Judith F. (2011). "When deaf signers read English: Do written words activate their sign translations?". Cognition. 118 (2): 286–292. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.11.006. PMC 3034361. PMID 21145047.

- Ottenheimer, Harriet Joseph (2012). The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Cengage. ISBN 978-1-133-70909-1.

- Papadatou-Pastou, Marietta; Ntolka, Eleni; Schmitz, Judith; Martin, Maryanne; Munafò, Marcus R.; Ocklenburg, Sebastian; Paracchini, Silvia (2020). "Human handedness: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 146 (6): 481–524. doi:10.1037/bul0000229. hdl:10023/19889. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 32237881. S2CID 214768754.

- Powell, Barry B. (2012) [2009]. Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-25532-2.

- Primus, Beatrice (2003). "Zum Silbenbegriff in der Schrift-, Laut- und Gebärdensprache—Versuch einer mediumübergreifenden Fundierung" [On the concept of syllables in written, spoken and sign language—an attempt to provide a cross-medium foundation]. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft (in German). 22 (1): 3–55. doi:10.1515/zfsw.2003.22.1.3. ISSN 1613-3706.

- ——— (2004). "A featural analysis of the Modern Roman Alphabet" (PDF). Written Language and Literacy. 7 (2). John Benjamins: 235–274. doi:10.1075/wll.7.2.06pri. eISSN 1570-6001. ISSN 1387-6732. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017.

- Rogers, Henry (2005). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23463-0.

- Sampson, Geoffrey (1985). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1254-5.

- ——— (2016). "Writing systems: Methods for recording language". In Allan, Keith (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics. London: Routledge. pp. 47–61. ISBN 978-0-415-83257-1.

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (1996) [1992]. How Writing Came About. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77704-0.

- Sproat, Richard (2010). Language, Technology, and Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954938-2.

- Steele, Philippa M. (2017). Understanding Relations Between Scripts. Oxford: Oxbow. ISBN 978-1-78570-644-8.

- ———; Boyes, Philip J., eds. (2022). Writing Around the Ancient Mediterranean: Practices and Adaptations. Contexts of and relations between early writing systems. Vol. 6. Oxford: Oxbow. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-78925-850-9.

- Tabouret-Keller, Andrée; Le Page, Robert B.; Gardner-Chloros, Penelope; Varro, Gabrielle, eds. (1997). Vernacular Literacy: A Re-Evaluation. Oxford studies in anthropological linguistics. Vol. 13. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823635-1.

- Baker, Philip. "Developing Ways of Writing Vernaculars: Problems and Solutions in a Historical Perspective". In Tabouret-Keller et al. (1997), pp. 93–141.

- Taylor, Insup; Olson, David R., eds. (1995). Scripts and Literacy: Reading and Learning to Read Alphabets, Syllabaries and Characters. Neuropsychology and Cognition. Vol. 7. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-94-010-4506-3.

- Scholes, Robert J. "Orthography, Vision, and Phonemic Awareness". In Taylor & Olson (1995), pp. 359–374.

- Threatte, Leslie (1980). The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions. Wilton de Gruyter. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-3-11-007344-7.

- Woods, Christopher; Emberling, Geoff; Teeter, Emily (2010). Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Oriental Institute Museum Publications. Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9.

External links

[edit]- The World's Writing Systems – all 294 known writing systems, each with a typographic reference glyph and Unicode status