Syngman Rhee

Syngman Rhee | |

|---|---|

| 이승만 | |

Official portrait, 1948 | |

| 1st President of South Korea | |

| In office 24 July 1948 – 26 April 1960 | |

| Prime Minister | See list

|

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Yun Po-sun |

| Speaker of the National Assembly | |

| In office 31 May 1948 – 24 July 1948 | |

| Preceded by | Kim Kyu-sik[a] |

| Succeeded by | Shin Ik-hee |

| Chairman of the State Council of the Korean Provisional Government | |

| In office 3 March 1947 – 15 August 1948 | |

| Deputy | Kim Ku |

| Preceded by | Kim Ku |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of the Korean Provisional Government | |

| In office 11 September 1919 – 23 March 1925 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Park Eunsik |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Rhee Syng-man 26 March 1875 Nungnae-dong, Taegyong-ri, Masan-myon, Pyongsan County, Hwanghae, Joseon |

| Died | 19 July 1965 (aged 90) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Resting place | Seoul National Cemetery |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party | Liberal (1951–1961) |

| Other political affiliations | National Association (1946–1951) People's Joint Association (1897–1899) |

| Spouses | |

| Alma mater | |

| Signature |  |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 이승만 / 리승만 |

| Hanja | 李承晩 |

| Revised Romanization | I Seungman / Ri Seungman |

| McCune–Reischauer | I Sŭngman / Ri Sŭngman |

| Art name | |

| Hangul | 우남 |

| Hanja | 雩南 |

| Revised Romanization | Unam |

| McCune–Reischauer | Unam |

| Part of a series on |

| Korean nationalism |

|---|

|

Syngman Rhee (Korean: 이승만; Hanja: 李承晚, pronounced [iː.sɯŋ.man];[b] 26 March 1875 – 19 July 1965) was a South Korean politician who served as the first president of South Korea from 1948 to 1960. Rhee is also known by his art name Unam (우남; 雩南).[1] Rhee was also the first and last president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea from 1919 to his impeachment in 1925 and from 1947 to 1948. As president of South Korea, Rhee's government was characterised by authoritarianism, limited economic development, and in the late 1950s growing political instability and public opposition.

Born in Hwanghae Province, Joseon, Rhee attended an American Methodist school, where he converted to Christianity. He became a Korean independence activist and was imprisoned for his activities in 1899. After his release in 1904, he moved to the United States, where he obtained degrees from American universities and met President Theodore Roosevelt. After a brief 1910–12 return to Korea, he moved to Hawaii in 1913. In 1919, following the Japanese suppression of the March First Movement, Rhee joined the right-leaning Korean Provisional Government in exile in Shanghai. From 1918 to 1924, he served as the first President of the Korean Provisional Government until he was impeached in 1925. He then returned to the United States, where he advocated and fundraised for Korean independence. In 1939, he moved to Washington, DC. In 1945, he was returned to US-controlled Korea by the US military, and on July 20, 1948 he was elected the first president of the Republic of Korea by the National Assembly, ushering in the First Republic of Korea.

As president, Rhee continued his hardline anti-communist and pro-American views that characterized much of his earlier political career. Early on in his presidency, his government put down the Jeju uprising on Jeju Island, and the Mungyeong and Bodo League massacres were committed against suspected communist sympathisers, leaving at least 100,000 people dead.[2] Rhee was president during the outbreak of the Korean War (1950–1953), in which North Korea invaded South Korea. He refused to sign the armistice agreement that ended the war, wishing to have the peninsula reunited by force.[3][4]

After the fighting ended, South Korea's economy lagged behind North Korea's and was heavily reliant on US aid. After being re-elected in 1956, he pushed to modify the constitution to remove the two-term limit, despite opposition protests. He was reelected uncontested in March 1960, after his opponent Chough Pyung-ok died from cancer before the election took place. After Rhee's ally Lee Ki-poong won the corresponding vice-presidential election by a wide margin, the opposition rejected the result as rigged, which triggered protests. These escalated into the student-led April Revolution, in which police shot demonstrators in Masan. The resulting scandal caused Rhee to resign on 26 April, ushering in the Second Republic of Korea. Despite this, protesters continued to converge on the presidential palace, leading to the CIA covertly evacuating him on 28 April by helicopter. He spent the rest of his life in exile in Honolulu, Hawaii, and died of a stroke in 1965.

Early life and career

[edit]Early life

[edit]Syngman Rhee was born on 26 March 1875 as Rhee Syng man in Daegyeong, a village in Pyeongsan County, Hwanghae Province, Joseon.[5][6][7][8] Rhee was the third but only surviving son out of three brothers and two sisters (his two older brothers both died in infancy) in a rural family of modest means.[5] Rhee's family traced its lineage back to King Taejong of Joseon. He was a 16th-generation descendant of Grand Prince Yangnyeong through his second son, Yi Heun who was known as Jangpyeong Dojeong (장평도정;長平都正).[9] This case makes him a distant relative of the mid-Joseon military officer, Yi Sun-sin (not be confused with Admiral Yi Sun-sin). His mother was a member of Gimhae Kim clan.

In 1877, at the age of two, Rhee and his family moved to Seoul, where he had traditional Confucian education in various seodang in Nakdong (낙동; 駱洞) and Dodong (도동; 桃洞).[10] When Rhee was six years old a smallpox infection rendered him virtually blind until he was treated with western medicine, possibly by a Japanese doctor.[11] Rhee was portrayed as a potential candidate for the gwageo, the traditional Korean civil service examination, but in 1894 reforms abolished the gwageo system, and in April he enrolled in the Paechae School (배재학당; 培材學堂), an American Methodist school, where he converted to Christianity.[5][7][8][12] Rhee studied English and sinhakmun (신학문; 新學問; lit. new subjects). Near the end of 1895, he joined a Hyeopseong (Mutual Friendship) Club (협성회; 協成會) created by Seo Jae-pil, who returned from the United States after his exile following the Gapsin Coup. He worked as the head and the main writer of the newspapers Hyŏpsŏnghoe Hoebo and Maeil Sinmun,[10] the latter being the first daily newspaper in Korea.[12] During this period, Rhee earned money by teaching the Korean language to Americans. In 1895, Rhee graduated from Pai Chai School.[5]

Independence activities

[edit]Rhee became involved in anti-Japanese circles after the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, which saw Joseon passed from the Chinese sphere of influence to the Japanese. Rhee was implicated in a plot to take revenge for the assassination of Empress Myeongseong, the wife of King Gojong who was assassinated by Japanese agents (known in Korean history as the Chunsaengmun incident); however, a female American physician Georgiana E. Whiting helped him avoid the charges by disguising him as her patient and go to his sister's house. Rhee acted as one of the forerunners of the Korean independence movement through grassroots organizations such as the Hyeopseong Club and the Independence Club. Rhee organized several protests against corruption and the influences of the Japan and the Russian Empire.[12] As a result, in November 1898, Rhee attained the rank of Uigwan (의관; 議官) in the Imperial Legislature, the Jungchuwon (중추원; 中樞院).[10]

After entering civil service, Rhee was implicated in a plot to remove King Gojong from power through the recruitment of Park Yeong-hyo. As a result, Rhee was imprisoned in the Gyeongmucheong Prison (경무청; 警務廳) in January 1899.[10] Other sources place the year arrested as 1897 and 1898.[5][7][8][12] Rhee attempted to escape on the 20th day of imprisonment but was caught and was sentenced to life imprisonment through the Pyeongniwon (평리원; 平理院). He was imprisoned in the Hanseong Prison (한성감옥서; 漢城監獄署). In prison, Rhee translated and compiled The Sino–Japanese War Record (청일전기; 淸日戰紀), wrote The Spirit of Independence (독립정신; 獨立精神), compiled the New English–Korean Dictionary (신영한사전; 新英韓辭典) and wrote in the Imperial Newspaper (제국신문; 帝國新聞).[10] He was also tortured.[12] Examples of this included Japanese officers lighting oil paper which were pushed up his fingernails, and then smashing them one-by-one.[13]

Political activities at home and abroad

[edit]

In 1904, Rhee was released from prison at the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War with the help of Min Young-hwan.[5] In November 1904, with the help of Min Yeong-hwan and Han Gyu-seol (한규설; 韓圭卨), Rhee moved to the United States. In August 1905, Rhee and Yun Byeong-gu (윤병구; 尹炳求)[10] met with US President Theodore Roosevelt at peace talks in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and attempted unsuccessfully to convince the US to help preserve independence for Korea.[14]

Rhee continued to stay in the United States; this move has been described as an "exile".[12] He obtained a Bachelor of Arts from George Washington University in 1907, and a Master of Arts from Harvard University in 1908.[5][9] In 1910,[5] he obtained a PhD from Princeton University[7][8] with the thesis "Neutrality as influenced by the United States" (미국의 영향하에 발달된 국제법상 중립).[10]

In August 1910, Rhee returned to Japanese-occupied Korea.[10][c] He served as a YMCA coordinator and missionary.[15][16] In 1912, Rhee was implicated in the 105-Man Incident,[10] and was shortly arrested.[5] However, he fled to the United States in 1912[7] with M. C. Harris's rationale that Rhee was going to participate in the general meeting of Methodists in Minneapolis as the Korean representative.[10][d]

In the United States, Rhee attempted to convince Woodrow Wilson to help the people involved in the 105-Man Incident, but failed to bring any change. Soon afterwards, he met Park Yong-man, who was in Nebraska at the time. In February 1913, as a consequence of the meeting, he moved to Honolulu, Hawaii, and took over the Han-in Jung-ang Academy (한인중앙학원; 韓人中央學園).[10] In Hawaii, he began to publish the Pacific Ocean Magazine (태평양잡지; 太平洋雜誌).[5] In 1918, he established the Han-in Christian Church (한인기독교회; 韓人基督敎會). During this period, he opposed Park Yong-man's stance on foreign relations of Korea and brought about a split in the community.[10] In December 1918, he was chosen, along with Dr. Henry Chung DeYoung, as a Korean representative to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 by the Korean National Association but they failed to obtain permission to travel to Paris. After giving up travelling to Paris, Rhee held the First Korean Congress in Philadelphia with Seo Jae-pil to make plans for future political activism concerning Korean independence.[10]

Following the March First Movement in March 1919, Rhee discovered that he was appointed to the positions of foreign minister for the Korean National Assembly (a group in Vladivostok), prime minister for the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai, and a position equivalent to president for the Hanseong Provisional Government. In June, in the acting capacity of the President of the Republic of Korea, he notified the prime ministers and the chairmen of peace conferences of Korea's independence. On 25 August, Rhee established the Korean Commission to America and Europe (구미위원부; 歐美委員部) in Washington, DC. On 6 September, Rhee discovered that he had been appointed acting president for the Provisional Government in Shanghai.[7][8] From December 1920 to May 1921, he moved to Shanghai and was the acting president for the Provisional Government.[10]

However, Rhee failed to efficiently act in the capacity of Acting President due to conflicts inside the provisional government in Shanghai. In October 1920, he returned to the US to participate in the Washington Naval Conference. During the conference, he attempted to set the problem of Korean independence as part of the agenda and campaigned for independence but was unsuccessful.[5][10] In September 1922, he returned to Hawaii to focus on publication, education, and religion. In November 1924, Rhee was appointed the position of president for life in the Korean Comrade Society (대한인동지회; 大韓人同志會).[10]

In March 1925, Rhee was impeached as the president of the Provisional Government in Shanghai over allegations of misuse of power[17] and was removed from office. Nevertheless, he continued to claim the position of president by referring to the Hanseong Provisional Government and continued independence activities through the Korean Commission to America and Europe. In the beginning of 1933, he participated in the League of Nations conference in Geneva to bring up the question of Korean independence.[10]

In November 1939, Rhee and his wife left Hawaii for Washington, DC.[18] He focused on writing the book Japan Inside Out and published it during the summer of 1941. With the attack on Pearl Harbor and the consequent Pacific War, which began in December 1941, Rhee used his position as the chairman of the foreign relations department of the provisional government in Chongqing to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the United States Department of State to approve the existence of the Korean provisional government. As part of this plan, he cooperated with anti-Japan strategies conducted by the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In 1945, he participated in the United Nations Conference on International Organization as the leader of the Korean representatives to request the participation of the Korean provisional government.[10]

-

Rhee in 1905 dressed to meet Theodore Roosevelt

-

Rhee and Vice President of the Korean Provisional Government Kim Kyu-sik in 1919

Presidency (1948–1960)

[edit]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in South Korea |

|---|

|

Return to Korea and rise to power

[edit]After the surrender of Japan on 2 September 1945,[19] Rhee was flown to Tokyo aboard a US military aircraft.[20] Over the objections of the Department of State, the US military government allowed Rhee to return to Korea by providing him with a passport in October 1945, despite the refusal of the Department of State to issue Rhee with a passport.[21] The British historian Max Hastings wrote that there was "at least a measure of corruption in the transaction" as the OSS agent Preston Goodfellow who provided Rhee with the passport that allowed him to return to Korea was apparently promised by Rhee that if he came to power, he would reward Goodfellow with commercial concessions."[21] Following the independence of Korea and a secret meeting with Douglas MacArthur, Rhee was flown in mid-October 1945 to Seoul aboard MacArthur's personal airplane, The Bataan.[20]

After the return to Korea, he assumed the posts of president of the Independence Promotion Central Committee (독립촉성중앙위원회; 獨立促成中央協議會), chairman of the Korean People's Representative Democratic Legislature, and president of the Headquarters for Unification (민족통일총본부; 民族統一總本部). At this point, he was strongly anti-communist and opposed foreign intervention; he opposed the Soviet Union and the United States' proposal in the 1945 Moscow Conference to establish a trusteeship for Korea and the cooperation between the left-wing (communist) and the right-wing (nationalist) parties. He also refused to join the US-Soviet Joint Commission (미소공동위원회; 美蘇共同委員會) as well as the negotiations with the north.[10]

For decades, the Korean independence movement was torn by factionalism and in-fighting, and most of the leaders of the independence movement hated each other as much as they hated the Japanese. Rhee, who had lived for decades in the United States, was a figure known only from afar in Korea, and therefore regarded as a more or less acceptable compromise candidate for the conservative factions. More importantly, Rhee spoke fluent English, whereas none of his rivals did, and therefore he was the Korean politician most trusted and favored by the American occupation government. The British diplomat Roger Makins later recalled, "the American propensity to go for a man rather than a movement — Giraud among the French in 1942, Chiang Kai-shek in China. Americans have always liked the idea of dealing with a foreign leader who can be identified as 'their man'. They are much less comfortable with movements." Makins further added the same was the case with Rhee, as very few Americans were fluent in Korean in the 1940s or knew much about Korea, and it was simply far easier for the American occupation government to deal with Rhee than to try to understand Korea. Rhee was "acerbic, prickly, uncompromising" and was regarded by the US State Department, which long had dealings with him as "a dangerous mischief-maker", but the American General John R. Hodge decided that Rhee was the best man for the Americans to back because of his fluent English and his ability to talk with authority to American officers about American subjects. Once it became clear from October 1945 onward that Rhee was the Korean politician most favored by the Americans, other conservative leaders fell in behind him.[citation needed]

When the first US–Soviet Cooperation Committee meeting was concluded without a result, he began to argue in June 1946 that the government of Korea must be established as an independent entity.[10] In the same month, he created a plan based on this idea[5] and moved to Washington, DC, from December 1946 to April 1947 to lobby support for the plan. During the visit, Harry S. Truman's policies of Containment and the Truman Doctrine, which was announced in March 1947, enforced Rhee's anti-communist ideas.[10]

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly recognized Korea's independence and established the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) through Resolution 112.[22][23] In May 1948, the South Korean Constitutional Assembly election was held under the oversight of the UNTCOK.[10] He was elected without competition to serve in the South Korean Constitutional Assembly (대한민국 제헌국회; 大韓民國制憲國會) and was consequently selected to be Speaker of the Assembly. Rhee was highly influential in creating the policy stating that the president of South Korea had to be elected by the National Assembly.[5] The 1948 Constitution of the Republic of Korea was adopted on 17 July 1948.[24]

On 20 July 1948, Rhee was elected president of the Republic of Korea[7][8][24] in the 1948 South Korean presidential election with 92.3% of the vote; the second candidate, Kim Ku, received 6.7% of the vote.[25] On 15 August the Republic of Korea was formally established in the south,[24] and Rhee was inaugurated as its first president.[5][10] The next month, on 9 September, the north also proclaimed statehood as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Rhee's relations with the chinilpa Korean elites who had collaborated with the Japanese were, in the words of the South Korean historian Kyung Moon Hwang, often "contentious", but in the end an understanding was reached in which, in exchange for their support, Rhee would not purge the elites.[26] In particular, the Koreans who had served in the colonial-era National Police, whom the Americans had retained after August 1945, were promised by Rhee that their jobs would not be threatened by him. Upon independence in 1948, 53% of South Korean police officers were men who had served in the National Police during the Japanese occupation.[27]

Cabinet

[edit]Political repression

[edit]

Soon after taking office, Rhee enacted laws that severely curtailed political dissent. There was much controversy between Rhee and his leftist opponents. Allegedly, many of the leftist opponents were arrested and in some cases killed. The most controversial issue has been Kim Ku's assassination. On 26 June 1949, Kim Ku was assassinated by Ahn Doo-hee, who confessed that he had been acting on the orders of Kim Chang-ryong. Ahn Doo-hee was described by the British historian Max Hastings as one of Rhee's "creatures".[29] It soon became apparent that Rhee's style of government was rigidly authoritarian.[30] He allowed the internal security force (headed by his right-hand man, Kim Chang-ryong) to detain and torture suspected communists and North Korean agents. His government also oversaw several massacres, including the suppression of the Jeju uprising on Jeju Island, of which South Korea's Truth Commission reported 14,373 victims, 86% at the hands of the security forces and 13.9% at the hands of communist rebels,[31] and the Mungyeong Massacre.

By early 1950, Rhee had about 30,000 alleged communists in his jails, and had about 300,000 suspected sympathizers enrolled in an official "re-education" movement called the Bodo League. When the North Korean army attacked in June, retreating South Korean forces executed the prisoners, along with several tens of thousands of Bodo League members.[2]

Korean War

[edit]Both Rhee and Kim Il Sung wanted to unite the Korean peninsula under their respective governments, but the United States refused to give South Korea any heavy weapons, to ensure that its military could only be used for preserving internal order and self-defense.[32] By contrast, Pyongyang was well equipped with Soviet aircraft, vehicles and tanks. According to John Merrill, "the war was preceded by a major insurgency in the South and serious clashes along the thirty-eighth parallel," and 100,000 people died in "political disturbances, guerrilla warfare, and border clashes".[33]

At the outbreak of war on 25 June 1950, North Korean troops launched a full-scale invasion of South Korea. All South Korean resistance at the 38th parallel was overwhelmed by the North Korean offensive within a few hours. By 26 June, it was apparent that the Korean People's Army (KPA) would occupy Seoul. Rhee stated, "Every Cabinet member, including myself, will protect the government."[34] At midnight on 28 June, the South Korean military destroyed the Han Bridge, preventing thousands of citizens from fleeing. On 28 June, North Korean soldiers occupied Seoul.

During the North Korean occupation of Seoul, Rhee established a temporary government in Busan and created a defensive perimeter along the Naktong Bulge. A series of battles ensued, which would later be known collectively as the Battle of Naktong Bulge. After the Battle of Inchon in September 1950, the North Korean military was routed, and the United Nations Command (UNC) and South Korean forces not only liberated all of South Korea, but overran much of North Korea. In the areas of North Korea taken by the UNC forces, elections were supposed to be administered by the United Nations but instead were taken over and administered by the South Koreans. Rhee insisted on Bukjin Tongil – ending war by conquering North Korea, but after the Chinese entered the war in November 1950, the UNC forces were thrown into retreat.[3] During this period of crisis, Rhee ordered the December massacres of 1950. Rhee was absolutely committed to reunifying Korea under his leadership and strongly supported MacArthur's call for going all-out against China, even at the risk of provoking a nuclear war with the Soviet Union.[35]

Hastings notes that, during the war, Rhee's official salary was equal to $37.50 per month. Both at the time and since, there has been much speculation about precisely how Rhee managed to live on this amount. The entire Rhee regime was notorious for its corruption, with everyone in the government from the President downwards stealing as much they possibly could from both the public purse and from United States aid. The Rhee regime engaged in the "worst excesses of corruption", with South Korean soldiers going unpaid for months as their officers embezzled their pay, equipment provided by the United States being sold on the black market, and the size of the army being bloated by hundreds of thousands of "ghost soldiers" who only existed on paper, allowing their officers to steal pay that would have been due had these soldiers actually existed. The problems with low morale experienced by the army were largely due to the corruption of the Rhee regime. The worst scandal during the war—indeed of the entire Rhee government—was the National Defense Corps Incident. Rhee created the National Defense Corps in December 1950, intended to be a paramilitary militia, comprising men not in the military or police who were drafted into the corps for internal security duties. In the months that followed, tens of thousands of National Defense Corps men either starved or froze to death in their unheated barracks, as the men lacked winter uniforms and food. Even Rhee could not ignore the deaths of so many and ordered an investigation. It was revealed that the commander of the National Defense Corps, General Kim Yun Gun, had stolen millions of American dollars that were intended to heat the barracks and feed and clothe the men. Kim and five other officers were publicly shot at Daegu on 12 August 1951, following their convictions for corruption.[36]

In the spring of 1951, Rhee—who was upset about MacArthur's dismissal as UNC commander by President Truman—lashed out in a press interview against Britain, whom he blamed for MacArthur's sacking.[37] Rhee declared, "The British troops have outlived their welcome in my country." Shortly after, Rhee told an Australian diplomat about the Australian troops fighting for his country, "They are not wanted here any longer. Tell that to your government. The Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and British troops all represent a government which is now sabotaging the brave American effort to liberate fully and unify my unhappy nation."[37]

During the Korean War armistice negotiations, one of the most contentious issues was the repatriation of prisoners of war (POWs). The United Nations Command advocated for the principle of voluntary repatriation, allowing POWs to choose whether to return to their home countries. In contrast, the communist side insisted on mandatory repatriation, demanding that all POWs be returned regardless of their preferences. This disagreement prolonged the negotiations, and an agreement was only reached on June 8, 1953. However, South Korean President Rhee Syngman strongly opposed the armistice, fearing it would leave South Korea vulnerable to future aggression and believing it failed to ensure the country’s long-term security. On June 18, 1953, Rhee unilaterally ordered the release of over 27,000 anti-communist POWs held in camps across South Korea, including those in Busan, Masan, and Daegu. This action shocked the United States, the United Nations, and the communist side, as it was perceived as a direct challenge to the ongoing armistice talks. The release also led to casualties, with dozens of POWs reportedly killed or injured during the process. Rhee’s decision to release the POWs is interpreted as serving multiple purposes. Domestically, it was framed as a gesture to grant freedom to anti-communist prisoners who refused to return to their communist home countries. Internationally, it was a bold political maneuver to assert South Korea’s agency in the armistice process and to pressure the United States into committing to South Korea's defense. Rhee was deeply dissatisfied with the armistice negotiations being conducted without active participation from the South Korean government. His actions aimed to ensure South Korea’s security through the signing of the Korea-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty. Although the unilateral release of POWs temporarily disrupted the armistice talks, it ultimately strengthened South Korea’s position in post-war negotiations. The Korea-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty was signed shortly after the armistice, guaranteeing U.S. military support for South Korea and solidifying its defense against future aggression.[38][39]

On July 27, 1953, the Korean War, often referred to as "one of the 20th century's most vicious and frustrating wars," ended without a clear victor. The Korean Armistice Agreement was signed by military commanders representing China, North Korea, and the United Nations Command (UNC), led by the United States. However, the Republic of Korea (ROK), under President Syngman Rhee’s leadership, refused to sign the agreement. Rhee strongly opposed the armistice, fearing it would cement the division of Korea and leave the South vulnerable to future attacks. Despite intense pressure from the United States and its allies, Rhee remained steadfast in his objections, demanding stronger security guarantees and a commitment to South Korea's defense. Although the armistice succeeded in halting active hostilities, it was not a formal peace treaty. To this day, no peace treaty has been signed, leaving the Korean Peninsula in a technical state of war. The armistice established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) as a buffer between North and South Korea, yet tensions remained high. Rhee’s opposition to the armistice was part of his broader geopolitical strategy. He sought to secure a long-term U.S. military presence in South Korea to deter future attacks and to strengthen the South’s position in the region. His refusal to endorse the armistice eventually led to the signing of the Korea-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty in October 1953, which guaranteed U.S. military support for South Korea and cemented its role as a key ally in East Asia during the Cold War.[40][41][42][43][44][45]

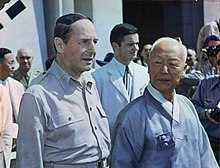

-

Rhee and his wife posing with Army Corps of Engineers personnel in 1950 at the Han River Bridge

-

Rhee on Time magazine cover, 1953

Re-election

[edit]Because of widespread discontent with Rhee's corruption and political repression, it was considered unlikely that Rhee would be re-elected by the National Assembly. To circumvent this, Rhee attempted to amend the constitution to allow him to hold elections for the presidency by direct popular vote. When the Assembly rejected this amendment, Rhee ordered a mass arrest of opposition politicians and then passed the desired amendment in July 1952. During the following presidential election, he received 74% of the vote.[46]

Post-war economic challenges

[edit]At the time of its creation in 1948, South Korea was among the poorest countries in the world. Twelve years later, in 1960, it held this position with a per capita income similar to that of Haiti. Although South Korea was predominantly an agricultural society that had experienced some industrialization during the Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945, mainly in the northern provinces, it faced significant challenges.[47]

The division of Korea in 1945 by the Soviet Union and the United States resulted in the creation of two states: the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in the north and the Republic of Korea in the south. The DPRK inherited most of the industry, mining, and more than 80% of electricity generation. In contrast, the ROK owned the majority of productive agricultural areas, but these were barely enough to feed a densely populated and rapidly growing population.[47]

The period after the war was marked by a very slow recovery, despite South Korea being one of the largest per capita recipients of foreign aid.[47] The lack of central planning, minimal investment in infrastructure, poor use of aid funds, government corruption, political instability, and the threat of renewed war with the North made the country very unattractive to both domestic and foreign investors. Additionally, the fear of recreating a colonial dependence on Japan prevented Seoul from opening the country to trade and investment with its prosperous neighbor.[47]

Resignation and exile

[edit]After the war ended in July 1953, South Korea struggled to rebuild following nationwide devastation. The country remained at a Third World level of development and was heavily reliant on US aid.[48] Rhee was easily re-elected for what should have been the final time in 1956, since the 1948 constitution limited the president to two consecutive terms. However, soon after being sworn in, he had the legislature amend the constitution to allow the incumbent president to run for an unlimited number of terms, despite protests from the opposition.[49]

In March 1960, the 84-year-old Rhee won his fourth term in office as president. His victory was assured with 100% of the vote after the main opposition candidate, Cho Byeong-ok, died shortly before the 15 March elections.[50][51]

Rhee wanted his protégé, Lee Ki-poong, elected as Vice President—a separate office under Korean law at that time. When Lee, who was running against Chang Myon (the ambassador to the United States during the Korean War, a member from the opposition Democratic Party) won the vote with a wide margin, the opposition Democratic Party claimed the election was rigged. This triggered anger among segments of the Korean populace on 19 April. When police shot demonstrators in Masan, the student-led April Revolution forced Rhee to resign on 26 April.[50]

On 28 April 1960, a DC-4 belonging to the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), piloted by Captain Harry B. Cockrell Jr. and operated by Civil Air Transport, covertly flew Rhee out of South Korea as protesters converged on the Blue House.[52] During the flight, Rhee and Francesca Donner, his Austrian wife, went to the cockpit to thank the pilot and crew. Rhee's wife offered the pilot a valuable diamond ring in thanks, which was courteously declined. The former president, his wife, and their adopted son subsequently lived in exile in Honolulu, Hawaii.[53]

Death

[edit]Rhee died of stroke complications in Honolulu on 19 July 1965.[54] A week later, his body was returned to Seoul and buried in the Seoul National Cemetery.[55]

Personal life

[edit]Rhee was married to Seungseon Park from 1890 to 1910. Park divorced Rhee shortly after the death of their son Rhee Bong-su in 1908, supposedly because their marriage had no intimacy due to his political activities.[citation needed]

In February 1933, Rhee met Austrian Franziska Donner in Geneva.[56] At the time, Rhee was participating in a League of Nations meeting[56] and Donner was working as an interpreter.[17] In October 1934, they were married[56] in New York City.[17][57] She also acted as his secretary.[56]

Over the years after the death of Bong-su, Rhee adopted three sons. The first was Rhee Un-soo, however, the elder Rhee ended the adoption in 1949.[58] The second adopted son was Lee Kang-seok, eldest son of Lee Ki-poong, who was a descendant of Prince Hyoryeong[59][60] and therefore a distant cousin of Rhee; but Lee committed suicide in 1960.[61][62] After Rhee was exiled, Rhee In-soo, who is a descendant of Prince Yangnyeong just like Rhee, was adopted by him as his heir.[63]

Legacy

[edit]

Rhee's former Seoul residence, Ihwajang, is currently used for the presidential memorial museum. The Woo-Nam Presidential Preservation Foundation has been set up to honor his legacy. There is also a memorial museum located in Hwajinpo near Kim Il Sung's cottage.[citation needed]

Rhee imbued South Korea with a legacy of authoritarian rule that lasted with only a few short breaks until 1988. One of those breaks came when the country adopted a parliamentary system with a figurehead president in response to Rhee's abuses. This Second Republic would only last a year before being overthrown in a 1961 military coup. In spite of this, however, the ensuing president Park Chung Hee expressed criticism of Rhee's regime, in particular for its lack of focus on economic and industrial development. Beginning with the Park era, the standing of Rhee and his "diplomatic" faction of the Korean independence movement fell in the public consciousness in favor of Kim Ku and Ahn Jung-geun, who embodied the "armed resistance" faction of the right-wing independence movement, who were preferred by Park; Kim's son Kim Shin and Ahn's nephew Ahn Chun-saeng both cooperated with the Park regimes of the Third and Fourth Republic.[64][unreliable source?]

Rhee began to be reevaluated after democratization in 1987, and in particular came to be associated with the so-called New Right movement, some members of which have argued that Rhee's achievements have been wrongly undervalued, and that he should be viewed positively as the founding father of the Republic of Korea.[65] An early and prominent example of such literature was Volume 2 of Re-Understanding the History of Pre- and Post-Liberation (해방 전후사의 재인식), published in 2006 by various "New Right" scholars. This academic dispute formed one of the germs behind the later history textbook controversies in the country.[citation needed]

In any event, this view has not spread much beyond the right-wing, with a 2023 Gallup Korea survey finding that only 30% of respondents saying that Rhee "did many good things", versus 40% who thought that he "did many wrong things" and 30% who had no opinion or didn't respond. Moreover, only about half of conservative party supporters, as well as half of self-described conservatives, gave the first response.[66]

In popular culture

[edit]- Portrayed by Lee Chang-hwan in the 1991–1992 MBC TV series Eyes of Dawn.

- Portrayed by Kwon Sung-deok in the 2006 KBS1 TV series Seoul 1945.

- In the M*A*S*H episode titled "Mail Call, Again", Radar mentions a parade in Seoul due to Syngman Rhee being "elected dictator again."[67]

- Rhee is referenced in the lyrics to singer Billy Joel's 1989 music single, "We Didn't Start the Fire".[68]

- Rhee is mentioned in Philip Roth's I Married a Communist.

- Rhee's new documentary film, The Birth of Korea (건국전쟁) was released in 2024, to re-establish his legacy and works.

- Season 3 of the left-wing podcast Blowback released in 2022 includes details about Rhee's rule, particularly his role as it related to U.S. Cold War foreign policy.

Works

[edit]- The Spirit of Independence (독립정신; 獨立精神; 1904)

- Neutrality as Influenced by the United States (1912)

- Japan Inside and Out (1941)

See also

[edit]- President of South Korea

- Francesca Donner

- Inha University

- Korean independence movement

- Korean National Association

- Cabinet of Rhee Syng-man

Notes

[edit]- ^ As Chairman of the Interim Legislative Assembly

- ^ See North–South differences in the Korean language § Consonants.

- ^ In 1910, the Korean Peninsula was officially annexed by the Empire of Japan.

- ^ He did participate in the meeting as the Korean representative.

References

[edit]- ^ 이승만 (李承晩). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b "South Korea owns up to brutal past – World – smh.com.au". www.smh.com.au. 15 November 2008.

- ^ a b Kollontai, Ms Pauline; Kim, Professor Sebastian C. H.; Hoyland, Revd Greg (2 May 2013). Peace and Reconciliation: In Search of Shared Identity. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4094-7798-3.

- ^ Cha (2010), p. 174

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n 이승만 [李承晩] [Rhee Syngman]. Doopedia (in Korean). Doosan Corporation. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Syngman Rhee". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Syngman Rhee: First president of South Korea". CNN Student News. CNN. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Syngman Rhee". The Cold War Files. Cold War International History Project. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ a b Cha, Marn J. (19 September 2012) [1996]. "Syngman Rhee's First Love" (PDF). The Information Exchange for Korean-American Scholars (IEKAS) (12–19): 2. ISSN 1092-6232. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w 이승만 [Rhee Syngman]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ It is sometimes erroneously claimed that Rhee was treated by American medical missionary Horace Allen. For a discussion of this topic see, Fields, Foreign Friends, p. 17–19

- ^ a b c d e f Breen, Michael (18 April 2010). "Fall of Korea's First President Syngman Rhee in 1960". The Korea Times. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ T. R. Fehrenbach (2000). This Kind of War (Pages 167-168). Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-878-1.

- ^ Yu Yeong-ik (유영익) (1996). 이승만의 삶과 꿈 [Rhee Syngman's Life and Dream] (in Korean). Seoul: JoongAng Ilbo Press. pp. 40–44. ISBN 89-461-0345-0.

- ^ Coppa, Frank J., ed. (2006). "Rhee, Syngman". Encyclopedia of modern dictators: from Napoleon to the present. Peter Lang. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8204-5010-0.

- ^ Jessup, John E. (1998). "Rhee, Syngman". An encyclopedic dictionary of conflict and conflict resolution, 1945–1996. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 626. ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9.

- ^ a b c Breen, Michael (2 November 2011). "(13) Syngman Rhee: president who could have done more". The Korea Times. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ O'Toole, George Barry; Tsʻai, Jên-yü (1939). The China Monthly. China Monthly, Incorporated. p. 12.

- ^ "Japan surrenders". History. A+E Networks. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b Cumings, Bruce (2010). "38 degrees of separation: a forgotten occupation". The Korean War: a History. Modern Library. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8129-7896-4.

- ^ a b Hastings, Max (1988). The Korean War. Simon and Schuster. pp. 32–34. ISBN 9780671668341.

- ^ – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Details/Information for Canadian Forces (CF) Operation United Nations Commission on Korea". Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "South Korea (1948–present)". Dynamic Analysis of Dispute Management Project. University of Central Arkansas. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Croissant, Aurel (2002). "Electoral Politics in South Korea" (PDF). Electoral politics in Southeast & East Asia. 370. Vol. VI. Singapore: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. pp. 234–237. ISBN 978-981-04-6020-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Kyung Moon Hwang A History of Korea Palgrave Macmillan, 2010 page 204.

- ^ Hastings (1988), p. 38

- ^ a b Charles J. Hanley & Hyung-Jin Kim (10 July 2010). "Korea bloodbath probe ends; US escapes much blame". San Diego Union Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Hastings (1988), p. 42

- ^ Tirman, John (2011). The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America's Wars. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-19-538121-4.

- ^ "The National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Jeju April 3 Incident". 2008. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ Hastings (1988), p.45

- ^ Merrill, John, Korea: The Peninsular Origins of the War (University of Delaware Press, 1989), p181.

- ^ "Ten biggest lies in modern Korean history". The Korea Times. 3 April 2017.

- ^ Koenig, Louis William (1968). The Chief Executive. Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 228.

- ^ Hastings (1988), p. 235-240

- ^ a b Hastings (1988), p. 235

- ^ National Archives of Korea. "반공포로 석방 사건." Accessed January 13, 2025. National Archives of Korea

- ^ "반공포로 석방 사건" (Release of Anti-Communist POWs), EncyKorea, The Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved from [1](https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0061616)

- ^ James E. Dillard. "Biographies: Syngman Rhee". The Department of Defense 60th Anniversary of Korean War Commemoration Committee. Retrieved on 28 September 2016.

- ^ "The Korean War armistice". BBC News. 5 March 2015. Retrieved on 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Armistice Agreement for the Restoration of the South Korean State." National Archives. Accessed January 13, 2025. [2](https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/armistice-agreement-restoration-south-korean-state).

- ^ "Long Diplomatic Wrangling Finally Led to Korean Armistice 70 Years Ago." U.S. Department of Defense. Accessed January 13, 2025. [3](https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3423473/long-diplomatic-wrangling-finally-led-to-korean-armistice-70-years-ago/).

- ^ "Korean War Armistice." Wilson Center Digital Archive. Accessed January 13, 2025. [4](https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/topics/korean-war-armistice).

- ^ "Armistice and Aid." Britannica. Accessed January 13, 2025. [5](https://www.britannica.com/place/Korea/Armistice-and-aid).

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2007). The making of modern Korea. Taylor & Francis. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-415-41482-1.

- ^ a b c d Seth, Michael J. (19 December 2017). "South Korea's Economic Development, 1948–1996". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.271. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Snyder, Scott A. (2 January 2018). South Korea at the Crossroads: Autonomy and Alliance in an Era of Rival Powers. Columbia University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-231-54618-8.

- ^ Kil, Soong Hoom; Moon, Chung-in (1 March 2010). Understanding Korean Politics: An Introduction. SUNY Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7914-9101-0.

- ^ a b Han, S-J. (1974) The Failure of Democracy in South Korea. University of California Press, p. 28–29.

- ^ Lentz, Harris M. (4 February 2014). Heads of States and Governments Since 1945. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-26490-2.

- ^ Cyrus Farivar (2011), The Internet of Elsewhere: The Emergent Effects of a Wired World, Rutgers University Press, p. 26.

- ^ "Madera Tribune 19 July 1965 — California Digital Newspaper Collection".

- ^ "Syngman Rhee Dies an Exile From Land He Fought to Free; Body of Ousted President, 90, Will Be Returned to Seoul for Burial". The New York Times. 20 July 1965. pp. 1, 30.

- ^ Dijk, Ruud van; Gray, William Glenn; Savranskaya, Svetlana; Suri, Jeremi; Zhai, Qiang (1 May 2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92310-5.

- ^ a b c d 프란체스카 [Francesca]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "KOREA: The Walnut". TIME. 9 March 1953. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

In 1932, while attempting to put Korea's case before an indifferent League of Nations in Geneva, Rhee met Francesca Maria Barbara Donner, 34, the daughter of a family of Viennese iron merchants. Two years later they were married in a Methodist ceremony in New York.

- ^ 정병준 (2005). 우남이승만연구. 역사비평사. pp. 56, 64.

- ^ 효령대군파 권37(孝寧大君派 卷之三十七). 장서각기록유산DB. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ 전주이씨효령대군정효공파세보 全州李氏孝寧大君靖孝公派世譜. FamilySearch. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Choy, Bong-youn (1971). Korea: A History. Tuttle Publishing. p. 352. ISBN 9781462912483.

- ^ Oh, John Kie-chiang (1999). Korean Politics: The Quest for Democratization and Economic Development. Cornell University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0801484588.

- ^ 전주이씨양녕대군파대보 全州李氏讓寧大君派大譜, 2권, 655–1980. FamilySearch. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Baek, Seung-dae (14 September 2014). 박정희가 띄운 김구, 어떻게 진보의 아이콘 됐나. OhmyNews (in Korean). Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Lee, Eun-woo (12 September 2023). "South Koreans Are Locked in a Battle Over Historical Interpretations". The Diplomat. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ 데일리 오피니언 제567호(2023년 11월 5주) - 역대 대통령 10인 개별 공과(功過) 평가 (11월 통합 포함). Gallup Korea. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "M*A*S*H s04e14 Episode Script G518 - Mail Call, Again". springfieldspringfield.co.uk. 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ We Didn't Start the Fire. BillyJoel.com. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Appleman, Roy E. (1998). South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Fields, David. Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Exceptionalism, and the Division of Korea. University Press of Kentucky, 2019, 264 pages, ISBN 978-0813177199.

- Lew, Yong Ick. The Making of the First Korean President: Syngman Rhee's Quest for Independence (University of Hawai'i Press; 2013). Scholarly biography; 576 pages.

- Shin, Jong Dae, Christian F. Ostermann, and James F. Person (2013). North Korean Perspectives on the Overthrow of Syngman Rhee. Washington, D.C.: North Korea International Documentation Project.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Syngman Rhee and Kim Ku, a 7 volume biography of Rhee and Kim Ku by Son Sae-il.

External links

[edit]- Syngman Rhee's FBI files hosted at the Internet Archive

- Syngman Rhee

- 1875 births

- 1965 deaths

- 19th-century Korean people

- Burials at Seoul National Cemetery

- Conservatism in South Korea

- Converts to Methodism

- Exiled politicians

- Far-right politics in South Korea

- First Republic of Korea

- George Washington University alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- House of Yi

- South Korean expatriates in China

- Korean nationalists

- Korean torture victims

- Liberal Party (South Korea) politicians

- Members of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

- People from Haeju

- People from North Hwanghae Province

- People of the Cold War

- Politicide perpetrators

- Presidents of South Korea

- Prime ministers of Korea

- Princeton University alumni

- Sadaejuui

- South Korean anti-communists

- South Korean expatriates in the United States

- South Korean Methodists

- Speakers of the National Assembly (South Korea)

- South Korean people of North Korean origin

- Perpetrators of political repression in South Korea

- Foreign nationals imprisoned in Japan

- Recipients of the Grand Order of Mugunghwa