Stabiae

Wall painting from Stabiae, 1st century AD | |

| Location | Castellammare di Stabia, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Southern Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°42′11″N 14°29′56″E / 40.70306°N 14.49889°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Pompei, Ercolano e Stabia |

| Website | Sito Archeologico di Stabiae (in Italian and English) |

Stabiae (Latin: [ˈstabɪ.ae̯]) was an ancient city situated near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia and approximately 4.5 km southwest of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, and being only 16 km (9.9 mi) from Mount Vesuvius, it was largely buried by tephra ash in the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in this case at a shallower depth of up to 5 m.[1]

Stabiae is most famous for the Roman villas found near the ancient city which are regarded as some of the most stunning architectural and artistic remains from any Roman villas.[2] They are the largest concentration of excellently preserved, enormous, elite seaside villas known in the Roman world. The villas were sited on a 50 m high headland overlooking the Gulf of Naples.[3][4] Although it was discovered before Pompeii in 1749, unlike Pompeii and Herculaneum, Stabiae was reburied by 1782 and so failed to establish itself as a destination for travellers on the Grand Tour.

Many of the objects and frescoes taken from these villas are now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

History

[edit]

The settlement at Stabiae arose from as early as the 7th century BC due to the favourable climate and its strategic and commercial significance as evocatively documented by materials found in the vast necropolis discovered in 1957 on via Madonna delle Grazie, situated between Gragnano and Santa Maria la Carità. The necropolis of over 300 tombs containing imported pottery of Corinthian, Etruscan, Chalcidian and Attic origin clearly shows that the town had major commercial contacts.[5] The necropolis, covering an area of 15,000 m2 (160,000 sq ft), was used from the 7th to the end of the 3rd century BC and shows the complex population changes with the arrival of new peoples, such as the Etruscans, which opened up new contacts.[6]

Stabiae had a small port which by the 6th century BC had already been overshadowed by the much larger port at Pompeii. It later became an Oscan settlement[7] and it appears that the Samnites later took over the Oscan town in the 5th century.

With the arrival of the Samnites the city suffered a sudden social and economic slowdown in favour of the development of nearby Pompeii, as shown by the almost total absence of burials: however, when the influence of the Samnites became more marked in the middle of the 4th century BC Stabiae began a slow recovery,[8] so much so that it was necessary to build two new necropoles, one discovered in 1932 near the Mediaeval Castle, the other in Scanzano. A sanctuary, probably dedicated to Athena, was built in the locality of Privati.[9]

It then became part of the Nucerian federation, adopting its political and administrative structure and becoming its military port, although it enjoyed less autonomy than Pompeii, Herculaneum and Sorrento; in 308 BC, after a long siege, it was forced to surrender in the Samnite wars against the Romans.

The earliest Roman evidence is coins from Rome and Ebusus found in the sanctuary of Privati dating back to the 3rd century BC probably brought in by merchants.[10] During the Punic Wars Stabiae supported Rome against the Carthaginians with young men in the fleet of Marcus Claudius Marcellus, according to Silius Italicus who wrote:

- Irrumpit Cumana ratis, quam Corbulo ducato lectaque complebat Stabiarum litore pubes.

The location of the early city of Stabiae is still to be identified but it was most probably a fortified town of some importance, since when conflict with the Romans reached a head during the Social War (91–88 BC), the Roman general Sulla did not simply occupy the town on 30 April 89 BC but destroyed it. Its location is said to be delimited by the Scanzano gorge and the San Marco stream which partly eroded its walls.

Roman Period

[edit]

The Roman author and admiral Pliny the Elder recorded that the town was rebuilt after the Social Wars and became a popular resort for wealthy Romans. He reported that there were several miles of luxury villas built along the edge of the headland, all enjoying panoramic views out over the bay.[4] The villas that can be visited today come from the time between the destruction of Stabiae by Sulla in 89 BC and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.[7]

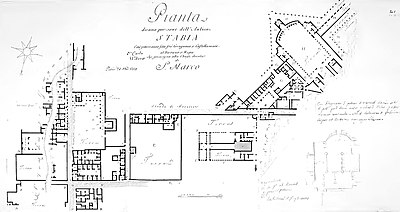

In 1759 Karl Weber identified and described part of the city near the Villa San Marco which extended over about 45000 m2. He found five paved streets intersecting at right angles, the forum, a temple on a podium, a gymnasium, tabernae with arcades, pavements and small private houses.

In the plain around Stabiae was the Ager Stabianus, the land administered by the city and an agricultural area in which about 60 villae rusticae have been identified: farmhouses that vary from 400 to 800 m2, from which intensive agriculture took advantage of the fertility of the soil, and which included production and processing of agricultural products with wine and olive presses, threshing floors and storehouses,[11] making the owners wealthy, considering the villas' thermal baths and frescoed rooms.[12]

Stabiae established itself as a luxury residential centre, so much so that Cicero wrote in a letter to his friend Marcus Marius Gratidianus:

- "For I doubt not that in that study of yours, from which you have opened a window into the Stabian waters of the bay, and obtained a view of Misenum, you have spent the morning hours of those days in light reading"[13]

The phenomenon of the construction of the luxury villas along the entire coast of the Gulf of Naples in this period was such that Strabo also wrote:

- "The whole gulf is quilted by cities, buildings, plantations, so united to each other, that they seem to be a single metropolis."[14]

Stabiae was also well known for the quality of its spring water according to Columella, which was believed to have medicinal properties.

- Fontibus et Stabiae celebres (Stabiae is also famous for its springs).[15]

The Eruption of 79 AD

[edit]In 62 AD the city was hit by a violent earthquake that affected the whole region, causing considerable damage to the buildings and creating the need for restoration work, which was never finished.[citation needed]

According to a letter written by his nephew,[16][non-primary source needed] Pliny the Elder was at the other side of the bay in Misenum when the eruption of 79 AD started. He sailed by galley across the bay, partly to observe the eruption more closely, and partly to rescue people from the coast near the volcano.[citation needed]

Pliny died at Stabiae the following day. This coincides with the arrival of the sixth and largest pyroclastic surge of the eruption caused by the collapse of the eruption plume.[17][full citation needed][verification needed] The very diluted outer edge of this surge reached Stabiae and left two centimetres of fine ash on top of the immensely thick aerially-deposited tephra which further protected the underlying remains.[citation needed][verification needed]

Post-eruption

[edit]

Unlike Pompeii, the eruption did not end human activity as about 40 years later the road to Nuceria was rebuilt, as its 11th milestone recovered from the cathedral site shows. Also Publius Papinius Statius (c. 45–96) asked in a poem for his wife to join him in what he called "Stabias renatas" (Stabiae reborn).[18] It continued to be an important centre for trade as the surrounding agricultural area needed a port and that of Stabiae was restored whilst that of Pompeii had been destroyed. In the 2nd c. AD new necropoles were created at Grotta S.Biagio (below the Villa Arianna), Santa Maria la Carità and Pimonte.

After the Crisis of the Third Century the city decreased in importance. Between the third and fourth centuries, as demonstrated by the discovery of a sarcophagus, were the first traces of a Christian community.[19] The fifth century saw the formation of the diocese with the first bishops Orso and Catello. In the 5th century it was known as a centre of the Benedictine Order.

Archaeology

[edit]

The archaeological remains at Stabiae were originally discovered in 1749 by Cavaliere Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre, an engineer working for King Charles VII of Naples.[20] These ruins were partially excavated by Alcubierre with help from Karl Weber between 1749 and 1775.[20] Weber was the first to make detailed architectural drawings and delivered them to the court of Naples. He proposed the systematic unearthing of the buildings and their display on site, in their context. In 1759 Weber partially identified and described part of the old city that extended over an area of about 45000 m2.[21] The ruins that had been excavated, however, were reburied.

A second excavation campaign until 1782 was assisted by the architect Franceso La Vega after Weber's death. He diligently collected all the preceding material to reconstruct the history of the excavations. He introduced new concepts for the first time about context, emphasising direct observation of ancient buildings in their landscape or in their historical and archaeological context. In seven years at Stabiae La Vega resumed excavations in some villas built on the plateau of Varanium[22] already partially excavated, the Villa del Pastore, Villa Arianna and Second Complex and extended research to a large number of villae rusticae in the ager stabianus and made precise reports. However he could not persuade the court to keep excavated buildings exposed and avoid their backfilling. So excavation of Stabiae continued with the usual technique of digging and backfilling.[23] The location of Stabiae was again widely forgotten.

In 1950[4] when Libero D'Orsi, an enthusiastic amateur, brought to light some rooms of Villa San Marco[24] and Villa Arianna[25] with the help of the maps from the Bourbon excavations, and also Villa Petraro, a domus found by chance in 1957 (in the commune of Santa Maria la Carità) but then reburied after a few years of study.[26] He also found parts of a residential area of the city about 300 m from Villa San Marco including remains of houses, shops, and parts of the macellum[27] to which roads from the port converged.[28] These remains were again reburied. News of the finds quickly attracted important visitors and nobility from all over Europe. Some of the most important frescoes were detached to allow better conservation and almost 9000 finds collected were housed locally. His work finally stopped in 1962 following lack of funds.[29]

The site was declared an archaeological protected area in 1957.

Sporadically, numerous remains of villas and necropolises were found; as when Villa Carmiano (now in commune of Gragnano) was excavated in 1963 then reburied; in 1967 part of the "Second Complex" and the Villa del Pastore resurfaced and was reburied in 1970;[30] in 1974 a villa belonging to the ager stabianus was discovered located in the current municipality of Sant'Antonio Abate but whose excavation has not yet been completed.[31] In addition other villas, especially rural ones, were discovered throughout the ager stabianus, especially between Santa Maria la Carità and Gragnano and all were reburied.

In 1980 the violent earthquake of Irpinia caused huge damage to the villas and destroyed part of the colonnade of the upper peristyle of Villa San Marco.[32] It caused the closure of the excavations to the public. Nevertheless, in 1981 part of the courtyard of Villa Arianna was found, inside which were two agricultural wagons, one of which was restored and put on view to the public. In the rest of the eighties and nineties, only maintenance and restoration works were carried out, except for a few important events, such as the discovery of substructures at Villa Arianna in 1994 and the gymnasium in 1997.[33] The archaeological site was reopened to the public in 1995.

The year 2004 saw an Italian-American collaboration between the Superintendency of Archaeology of Pompeii, the region of Campania and the University of Maryland to form the non-profit Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation (RAS) whose goal was to restore and build an archaeological park.[34]

The year 2006 was eventful: following clearance on the Varano hill, rooms belonging to the Villa of Anteros and Heracles, already discovered by the Bourbons in 1749, but reburied and lost, were brought to light. In July the RAS revealed the upper peristyle of Villa San Marco and in its south-east corner Stabiae's first human skeleton was also found, probably a fugitive who fell victim to falling debris.[35]

In 2008 Villa San Marco and Villa Arianna were re-explored and in the former three cubicula were uncovered areas behind the peristyle and two latrines, and a garden was brought to light, with the latter part of the great peristyle looking directly over the sea.

In 2009 new excavations brought to light a Roman road running along the northern perimeter of Villa San Marco. It is a paved road that connected the town of Stabiae with the seashore below: across this artery is a gate to the city and along the walls are a myriad of graffiti and small drawings in charcoal. On the other side of the road, a baths area of a new villa was discovered, partly explored in the Bourbon era. A Roman road also led to the entrance of a domus belonging to the "Ager stabianus". In May 2010 a villa dating to the first century was discovered during the work to double the railway track of the Torre Annunziata-Sorrento line of the Circumvesuviana, between the stations of Ponte Persica and Pioppaino.

From 2011 to 2014, Columbia University and H2CU (Centro Interuniversitario per la Formazione Internazionale) have been excavating in the Villa San Marco, investigating it as a Roman elite structure and the pre-79 AD history of the site.[36]

In 2019 excavations in the Piazza Unità d'Italia unearthed an Augustan or Julio-Claudian building and a 4th-century building.[37][19]

Villas

[edit]

Among the many villas found at Stabiae are firstly large leisure villas (villa otium) without agricultural buildings such as:

- Villa San Marco

- Villa Arianna

- the Second Complex

- Villa del Pastore

- Villa del Fauno (or of Anteros and Heracles)

and secondly residential villas with agricultural sections (villa rustica) such as:

- Villa del Petraro

- Villa Carmiano (Villas A and B)

- Villa Sant'Antonio Abate

- Villa Medici

- Villa del Filosofo (of the Philosopher)

- Villa Marchetti

- Villa detto Carmiano in Masseria Buonodono

- Villa Petrellune

- Villas in Ogliaro

- Casa dei Miri

- Villa Sassole

Villa San Marco

[edit]

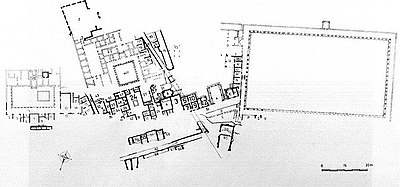

One of the largest villas ever discovered in Campania, it measured more than 11,000 m2,[4] although only half has been excavated. It was being renovated at the time of the eruption as shown by building materials present and displaced artefacts. Nevertheless, it was lavishly decorated with frescoes, with stucco work, floor mosaics and wall mosaics all of very high artistic quality, many of which were removed and are now held in museums.

This villa derived its name from a nearby chapel that existed in the 18th century. It was the first to be explored in the excavations in Bourbon times between 1749 and 1754.[38] The villa was re-buried after the removal of its furnishings and of the better-preserved frescoes. Excavations were resumed in 1950 by Libero d’Orsi and O. Elia of the Archaeological Superintendency.[39]

The villa was built at least in part on a 6th c. BC platform that may have levelled the ground on the hill.[40] Construction started at the latest in Augustus' reign and was significantly enlarged with the garden and swimming pool under Claudius.[41] The owner's name is not exactly known but it could belong to a certain Narcissus, a freedman, on the basis of stamps found on tiles, or to the Virtii family who had tombs not far away.

It has an entrance atrium (44) containing a pool, a oecus triclinaris (banqueting hall) (16) with views of the bay, and several colonnaded courtyards. There are also many other small rooms, a kitchen and two internal gardens. This villa is also important because it has provided frescoes, sculptures, mosaics and architecture, which show styles and themes comparable to those found in Pompeii and Herculaneum.[42]

The great peristyle (9) is surrounded by a long porch with a central pool (15) of 36×7 m which at the end has a nymphaeum (64,65) that has yet to be explored, decorated with frescoes depicting Neptune, Venus and several athletes, that were removed by the Bourbons and are now at the Naples museum and the Condé Museum in Chantilly, France. In the peristyle garden large plane trees grew and their root cavities were found; just as with the casts of humans these cavities were filled with plaster to make casts and archaeologists have also calculated that their age ranged from 75 to 100 years.

The villa has an even larger second peristyle on the southern side, partially excavated, approximately 140m long, with arcades supported by spiral columns which collapsed during the 1980 Irpinia earthquake: the ceilings are painted with scenes depicting Melpomene, the Apotheosis of Athena etc. In this peristyle was a sundial found during the excavation in a deposit as the villa at the time of the eruption was under renovation; the sundial was subsequently placed in its original position.

The baths of the villa are of considerable size on a triangular plot. The remains of the frescoes show they were finely decorated with depictions of large pendulous branches. Access to the baths is via an atrium, painted with wrestlers and boxers, followed by apodyterium, tepidarium, frigidarium, palaestra and caldarium: the pool in the caldarium, accessible by stone steps, is 7x5m and 1.5m deep. In excavations in the pool, part of the bottom was removed exposing a large brick furnace heating a large bronze boiler which was removed in 1798 by Lord Hamilton to be transported to London, but during the trip the Colossus was shipwrecked. The caldarium was covered with marble slabs. From the baths there are a number of ramps connecting the villa with the shore.

Art from Villa San Marco

[edit]-

Fresco of woman with tray

-

Fresco of winged figure

-

Fresco of a tree

-

Fresco detail of a planisphere (Antiquarium)

-

Skyphos in obsidian with incastonatura (Naples Museum)

Villa Arianna

[edit]

Named for the fresco depicting Dionysus saving Ariadne from the island of Dia (a mythological name for Naxos), this villa is particularly famous for its frescoes, many of which depict light, winged figures. Notably some of the most exquisite and famous Roman frescoes were found in bedrooms 23 to 26 on Weber's plan, the latter room having an especially fine decor with 18 outstanding frescoes.[43]

It is the oldest villa d'otium (a leisure villa) in Stabiae, dating back to the 2nd century BC.[44] The villa was extended over the course of 150 years. It is skilfully designed so that the residential quarters take advantage of the panorama along the ridge overlooking the Bay of Naples. It occupies an area of about 11000 sqm. of which only 2500 have been excavated. Some of the rooms were lost as a result of landslides on the slope.

Another feature is its private tunnel system that links the villa from its location on the ridge to the sea shore, which was probably only between 100 and 200 metres away from the bottom of the hill in Roman times. The shoreline has since changed, leaving the site further inland than it was in antiquity.[45]

It was first excavated between 1757 and 1762[46] when the villa was called the "First Complex" to distinguish it from the "Second Complex", from which it is separated by a narrow alley. The excavations were resumed by D'Orsi in 1950. In 2008 the large peristyle, one of the largest of any Roman villa at 370m in length, was brought to light almost completely, along with new rooms, columns and windows.

Layout

[edit]It has a complex plan, the result of several expansions of the building and was conveniently divided into four sections: the atrium, the thermal baths, the triclinium and the peristyle.

The "Tuscan" atrium, dating back to the late Republican age, is paved with white-black mosaic and has wall frescoes, often female figures and palmettes on a black and red background attributable to the third style. At the centre of the atrium is an impluvium while all around are numerous rooms: two of these, placed at the ends of the entrance of the atrium, preserve decorations that imitate architectures such as Ionic columns that support the coffered ceiling belonging to the second style.

In the other rooms the most important frescoes of all of Stabiae were found, all removed in the Bourbon era and preserved in the National Archaeology Museum of Naples. They include the Flora or Primavera found in 1759; it has a size of only 38x22 cm and dates to the first century BC: the fresco represents the Greek nymph Flora, understood by the Romans as the goddess of Spring, turning round in the act of collecting a flower, an allegory of purity, all on a pale-green background; Flora is certainly the best known work of Stabiae, so much so that it has become its symbol, not only in Italy, but also abroad.

Another work of great importance is the "Seller of cupids", found in 1759, also dating to the first century BC, which represents a woman in the act of selling a cupid to a girl: this fresco was already famous across Europe in the 18th century, influencing neoclassical taste and was copied on porcelain, prints, lithographs and paintings.

The triclinium directly overlooks the edge of the hill and dates from Nero's reign. On the centre of the rear wall is the fresco found in 1950 of the myth of Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus on the island of Naxos in the arms of Hypno escorted by Dionysus (represented with hawk eyes).

The bath area is smaller than the other villas in Stabiae, nevertheless there is an apsed calidarium with bath, a tepidarium and a frigidarium. In 2009 a large garden of 110x55 m was found, considered as the best preserved in the world, as the traces of the plants present at the time are still clearly visible.[47] There are also numerous service areas such as the kitchen, a fishpond, a masonry staircase leading to the first floor and a stable, where two agricultural carts were found,[48] one of which has been restored and on show to the public: this wagon has two large wheels made of iron and wood; in the immediate vicinity the skeleton of a horse with its hind legs raised was found, having become frightened by the eruption. The horse's name, Repentinus, is also known from an inscription in the stable.

-

Fresco showing a woman looking in a mirror as she dresses (or undresses) her hair, from the Villa of Arianna at Stabiae (Castellammare di Stabia), Naples National Archaeological Museum

-

Fresco depicting a seated woman, from the Villa Arianna at Stabiae, Naples National Archaeological Museum

-

Nereid on sea-horse

-

Nereid on sea-panther

-

Duck, Roman fresco from Villa Arianna, Naples Museum

-

Cupid seller

-

Roman cart

The Second Complex

[edit]

The so-called Second Complex is a villa otium located on the edge of the Varano hill between the Villa del Pastore and Villa Arianna and separated by a narrow alley from the latter which because of its proximity is often confused as the same villa. The site was explored for the first time in 1762 by Karl Weber, in 1775 by Pietro La Vega and finally in 1967 by Libero D'Orsi: only about 1000 m2 has been brought to light.

The villa consists of two areas, the oldest around the peristyle which was built around the first century BC and the later part, probably widening or emerging out of an existing structure, dating back to the imperial age. The peristyle has a portico on three sides and different areas including an oecus (lost following a landslide), and several scenic areas that looked out on the sea. On the west side there is a square fish pond with lead pipes and water spouts. The south side is a pseudoportico adorned with columns resting on a wall, behind which lies the baths that includes a caldarium with a bathtub, a tepidarium also with tub and garden and a laconicum with domed roof and a kitchen. On the north side next to Ariana Villa are a triclinium, and a cubiculum.

Most of the villa's objects were taken away by the Bourbons, as well as part of the black and white geometric tessellated pavement; however, the black walls in the third style are well preserved.

-

Second Complex

-

Fresco, Villa Arianna

-

Fragments from Second Complex

Villa del Pastore

[edit]

"Villa of the Shepherd" in English, this villa gets its name from a small statue of a shepherd that was discovered at this site. The villa, at 19,000 m2 area, is one of the very largest ever discovered and is even larger than Villa San Marco with many rooms, large baths and luxurious gardens. It lacks, however, any domestic rooms suggesting that it may not have been a residence. One hypothesis is that it is instead a valetudinarium[49] (health spa or a sort of domestic hospital and infirmary for sick slaves) to allow people to take advantage of the famous spring waters of Stabiae.

The villa stands on the edge of the plateau Varano with a panoramic view, a short distance from Villa Arianna. It was explored three times: its discovery dates back to 1754 to 1759 when Karl Weber brought to light a large garden; the second campaign under Pietro la Vega was carried out between 1775 and 1778; the third and final exploration dates to 1967–68 when the villa was rediscovered following the discovery of a perimeter wall after removal of a layer of lapilli on agricultural land. This excavation was funded by the landowner and the superintendent at the time tried to expropriate church land in the area between Villa Arianna and Villa San Marco in order to combine the areas of the villas of Stabiae. While waiting for the permit, the villa was re-buried in 1970 to prevent it from ruin. As a result of various bureaucratic problems related to the expropriation, the villa remains buried and has not yet been fully excavated.[50]

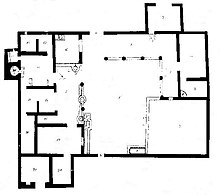

The Villa del Pastore dates from between the eighth century BC and 79 AD. It is divided into two parts: a large outdoor area and a series of residential rooms. The garden area is bordered to the south by the semicircular wall, while on the north is a 140m long cryptoporticus which runs parallel to a colonnade on a slightly lower level. At the centre of the garden is a swimming pool (natatio) with marble staircase. In the centre of the semicircular alcove was found the statue that gives the villa its name, of marble, 65 cm tall in Hellenistic style and is an old shepherd dressed in hides, carrying on his shoulders a kid, with a basket with grapes and bread on his left hand while in the right hand is a hare. Also in the garden to the south west is a porch 10x2m portico paved with black and white mosaic. Also a small square nymphaeum was found in the centre of which was placed a marble labrum.

The second part of the villa has fifteen rooms around a central courtyard, on the north side of which lies the baths area in which is located an apodyterium, a steam bath, a kitchen and a vestibule.

The villa is spread over three levels as revealed by recent landslides, including a number of substructures which had the dual function of containment of the hill and as the villa's support base. Like the other villas nearby, it was directly connected to the sea by a series of ramps sloping toward the beach.

Villa of Anteros and Heracles

[edit]

Situated on the Varano plateau, this villa otium (also known as the Villa del Fauno or Villa Chapel San Marco) is situated on the border between Castellammare di Stabia and Gragnano, a few meters from Villa San Marco.[51] It was the first Stabian villa to be excavated during the Bourbon excavations of the ancient town in 1749 and was explored again by Karl Weber in 1779. After being investigated and plundered of all items considered of value it was reburied.

The site was lost until 2006 when a group of volunteers clearing the Varano ridge witnessed a landslide which brought to light various structures, including a doorway and the hinge of a door. After the initial enthusiasm and initiatives to recover the remains, lack of funds has led to villa becoming overgrown again.

Most of what is known of the villa derives from the descriptions of the Bourbons.

In the southwest corner of a small peristyle were the remains of a lararium. In the niche was the figure of a young Julio-Claudian woman with a brooch, perhaps Livia or Antonia Minor, adorned with curly hair and now held in the Naples museum (inv. 6193). An altar was found next to it and on the wall above it was a plaque about 1.5m wide in red letters from the Augustan or Tiberian era that read:[52]

- ANTEROS L HERACLIO SUMMAR MAG LARIB ET FAMIL D D

It reports the dedication of a gift, perhaps the altar itself, to the Lares and the Familia by the freedman Anteros and the servant Heracleus, an employee of the administration of finance, both magistratus, officials of the cult.

They had the tasks of keeping the documents of the village, collecting taxes and organising festivals. Also discovered was a large number of scales and coins, sometimes in gold.

A cameo depicting a woman, perhaps Venus, holding a branch was also found.

From the excavation journal and the detailed plan of La Vega, the villa was composed of three parts: the service area around the small peristyle with a statue-fountain of a Faun lying on a stone, which gave the villa its name and which seems out of place. To the west is a symmetrical sector with reception and living rooms decorated with paintings and mosaic floors. To the south is a triple portico with double row of columns, of which the lower side along the panoramic edge of about 46 m was excavated. The 18th c. documentation shows it was a villa otium owing to its large size (almost 6000 m2). Its position and resemblance to the neighbouring Villa San Marco also suggests it was an imperial property.

Villa Petraro

[edit]The villa[53] is located on Via Cupa S. Marco, Petraro, on the border with Santa Maria la Carità. The villa was on the Sarno plain, a wooded area close to the Roman paved road between Stabia and Nuceria.

It was discovered in 1957 during industrial lapilli extraction and its exploration continued until 1958, followed by Libero D'Orsi, when after stripping it of frescoes and the best artworks it was reburied.[54]

It comprised an estate with a working farm dating from before AD 14.[55] When the eruption struck it was being renovated and being converted to a villa otium, as evidenced by heaps of building decoration materials, probably because of its situation overlooking the sea. Among the finds were blown-glass bottles, terracotta jugs and an oil press.

It had a large courtyard with cryptoporticus, an oven and a well. The rooms branch off from the central area: there are workspaces, triclinia, cubicula and six ergastula, or cells for slaves.

Following the renovation, the eastern part of the villa was equipped with a spa composed of a calidarium with a barrel-vaulted roof, a frigidarium in which new pools were under construction, a tepidarium equipped with clay pipes for heating the room, a furnace and an apodyterium, the changing room.[56] The decorative panels represented bucolic scenes, river gods, cupids and mythological representations such as Pasifae with Narcissus reflected in the water, Psyche, a Satyr with goat and a Satyr with rhyton; however, most of the walls of the villa had been covered with white plaster as well as twenty-five unfinished fine stucco panels.[54]

-

Unfinished stucco panels

Villa Carmiano (Villa A)

[edit]The villa was one of two nearby in Carmiano, Gragnano, excavated by Libero D'Orsi from 1963 but re-buried in 1998. Many fine frescoes were found and removed for preservation.[57]

It is a rustic villa of the ager stabianus located just under a kilometre from the plateau of Varano. It has an area of 400 m2 and dates from the end of the 1st c. BC. The quality of the paintings indicates that the owner was a wealthy farmer.[58] The most important works come from the triclinium such as the representation of Neptune and Amymone, Bacchus and Ceres and the Triumph of Dionysus.

The entrance includes a dog's kennel. The atrium has a lararium dedicated to Minerva. The service rooms include a wine press, tank for the collection of the must and a wine cellar with twelve dolia with a total capacity of seven thousand litres. The rooms used for the storage of the crop and tools for working the land are paved in clay, while the residential areas such as the triclinium, finely decorated with paintings in Flavian art, has tiled floors.

A seal with the letters MAR . A . S found during excavations may record the first name of the patron MAR, followed by the initial of the gens (family) A and then the word S(ervi).

-

Triumph of Dionysus

-

Villa Sant'Antonio Abate

[edit]This is a villa rustica in Casa Salese in the upper part of Sant'Antonio Abate and was in the outskirts of the ager stabianus on the border with Pompeii and Nuceria. It was discovered in 1974 and provided important information on Roman life. Having never been excavated before, not even by the Bourbons, it contained a great variety of objects.[59] It is thought that only one wing of the villa was brought to light. In 2009, a restoration and recovery project was approved for €40,000.

The villa dates to the Augustus-Tiberius era and is probably built around a square courtyard. The area found is a large room near the perimeter wall with a small farmyard enclosed by lower walls and three square-base columns as part of a portico in the entrance to the villa, decorated with images of animals, plants and masks.

Villa Medici

[edit]

Named after its locality, it was explored by la Vega in 1781–2. The villa has a rectangular plan with a courtyard in the centre with six columns frescoed in red, a dolium, a well and a basin with a canal that served as a drinking trough for animals. From the courtyard there are a series of rooms such as the kitchen with oven, a latrine, an apotheca[60] (upstairs store-room) where fruits were collected and laid on a straw bed[61] and a torcularium (a shed or out-house where the presses for oil or wine were worked[62]), which in turn gives access to a large frescoed room with a yellow plinth and red stripes while the upper part has green bands on a dark background with drawings of flowers and leaves. In this room were found a cup, a bell and an axe. There is also a wine cellar.

Villa del Filosofo

[edit]

It was found in 1778 and owes its name to the discovery of a ring adorned with a carved cornelian depicting the bust of a philosopher. The villa had not been disturbed since the eruption in 79 and many portable objects were found including the ring and an ivory needle with Venus, agricultural tools, terracotta objects, candelabra, bronze vases and the skeleton of a horse.[63]

It is located near the Villa Casa dei Miri and the great villas of Stabiae.

The villa was built around a courtyard with a windowed cryptoporticus on the north and arcades on the south and east sides, while in the centre there is a tufa altar and a well for water collection. Around the courtyard are rooms for residential and farming use. There is a spa area paved with a white mosaic with a dolphin in black entwining a rudder, while the walls are frescoed with paintings of animals and masks. One of the most beautiful frescoes represents Venus.

Villa Marchetti

[edit]The villa Marchetti located in Santa Maria La Carità was a very large villa, over 2000 sqm. where, in addition to the cultivation of grapes (wooden poles were found for the vineyard), horses and cattle were bred, cereals were grown, and the production cycle was completed with the mill and cooking in the ovens. Cheese was probably produced, as evidenced by a bronze boiler. Large lead pipes and hydraulic valves, found near the villa and along the roads (for example in the current Piazza Trivione and throughout the Carmiano area), are testimony to the extent of services in use. A housing block for 14 slaves was found.

Villa detto Carmiano in Masseria Buonodono

[edit]

The part of the villa shown in red was excavated in 1762 while the rest was done in 1781.[64] It was centred around a peristyle and an olive mill was found in the torcularium.[65] Several agricultural implements were found including hoes, a hammer and amphorae.

Villa Casa dei Miri

[edit]This is a villa rustica excavated in 1779–80 and is near the villas of otium of ancient Stabia. It is divided into residential and the rustic areas; the living area consists of an entrance portico with three columns, in which a staircase leads to the upper floor and divides the entrance from a small atrium. Around this are several rooms and a doorway into a large peristyle with twenty columns, with frescoed walls and floors decorated with mosaics and marble opus sectile. There are also thermal baths.[66]

The agricultural part includes a series of rooms mainly for the production of oil as evidenced by the discovery of two oil presses with a tank. There is also a farmyard in which an unusual terracotta pot was found, divided into various compartments used to fatten dormice, one of the favourite foods of the Romans.[63]

Temples

[edit]

The almost total absence of temples in the central Stabiae area suggests that these were most likely razed to the ground during the occupation of Sulla: however, some remains suggest the presence of various sacred structures such as a temple dedicated to Hercules, Diana, Athena, Cybele and most importantly the Genius Stabianum.

The temple of Hercules was located on the rock of Rovigliano (Petra Herculis), a limestone islet about 200 metres from the coast. The name Rovigliano derives either from an ancient Roman family name, the gens Rubilia or from the consul Rubelio, owner of the rock, or from the Latin term robilia the leguminous plants which grew abundantly in the ager area. Few traces of the temple of Hercules survived but include a wall in opus reticulatum, and a bronze statue representing Hercules which has since been lost.

The temple of Diana was located in the hamlet of Pozzano at the southern end of the ager stabianus on the hill near the basilica of the Madonna di Pozzano. In 1585 remnants were found in the church garden including an altar with deer heads, flowers and fruits, which is now kept in the Villa San Marco.

The temple of Athena was brought to light in 1984 in the Privati area, on the banks of the Rivo Calcarella, over an area of about 200 square metres. The temple dates from the Samnite period, probably built around the 4th century BC and contained a large quantity of artifacts. Among the most important finds found in this temple is a relief of the head of Hercules, of Hellenistic inspiration, made between the fourth and third century BC.

The temple of Cybele was discovered in 1863, in Trivione, Gragnano, during widening of a road.

The temple of the Genius Stabianum was brought to light in 1762 and after its exploration reburied. It is supposed to be between the hill of Varano and Santa Maria Charity. A plaque commemorated that the temple was restored after the earthquake of 62 and that the work had been carried out by Caesius Daphnus.

Necropoles

[edit]Several necropoles have been identified and explored in the area of Ager Stabianus, in particular those along the roads that lead to Pompeii, Nocera and Sorrento. The most important are located near Madonna delle Grazie, Gragnano and in the hilly ancient area of Castellammare di Stabia near the Medieval Castle and the cathedral. These necropoles have many children's tombs, testifying to high infant mortality.[67]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio; Anna Maria Sodo, Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Cultura e archeologia da Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006. ISBN 88-8090-126-5 p. 117-118

- ^ Stabiae: Master Plan 2006, the Archaeological Superintendancy of Pompeii, School of Architecture of the University of Maryland, The Committee of Stabiae Reborn

- ^ "San Diego Museum of Art exhibition on Stabiae". Archived from the original on 10 February 2006.

- ^ a b c d Restoring Stabiae website

- ^ "Homepage – Pompeii Sites Portale Ufficiale Parco Archeologico di Pompei". Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Homepage – Pompeii Sites Portale Ufficiale Parco Archeologico di Pompei". 9 March 2024.

- ^ a b Felice Senatore (2003). Stabiae: Dalla preistoria alla guerra greco-gotica. Edizioni Spano. ISBN 88-88226-15-X.

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio and Anna Maria Sodo, Stabia: history and architecture: p. 13. 250th anniversary of the Stabiae excavations 1749–1999, Rome, The Hermes of Bretschneider, 2004, ISBN 978-88-826-5201-2 .

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio, Anna Maria Sodo and Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Culture and Archeology from Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, p. 16. Longobardi Editore, 2006, ISBN 88-8090-126-5

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio, Anna Maria Sodo and Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Culture and Archeology from Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006, ISBN 88-8090-126-5. p.16

- ^ Giuseppe Cosenza, Stabia , Trani, Tipografica Editrice Vecchi, 1907.

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio; Anna Maria Sodo, Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Cultura e archeologia da Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006. ISBN 88-8090-126-5 p. 23

- ^ Cicero, Letter XIX: ad familiares 7.1

- ^ Strabo Geography 5.4.8

- ^ Columella, Libri X, de cultu hortorum 133

- ^ "Account of Pliny's death, in Latin and English". Archived from the original on 17 October 2006.

- ^ Francis, Peter & Oppenheimer, Clive (2004). Volcanoes. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199254699.[page needed]

- ^ Statius, Silvae 3.5, 104: Ad Uxorem Claudiam

- ^ a b "Castellammare di Stabia. Torneranno sottoterra i reperti archeologici emersi in Piazza Unità d'Italia durante gli scavi per il parcheggio". Positanonews (in Italian). 25 September 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ a b Parslow, Christopher Charles (1995). Rediscovering Antiquity: Karl Weber and the Excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47150-8.

- ^ Gardelli, Paolo. Stabiae and the Beginning of European Archaeology: From Looting to Science. Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art: Collection of articles. Vol. 8. Ed. S. V. Mal’tseva, E. Iu. Staniukovich-Denisova, A. V. Zakharova. St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg Univ. Press, 2018, pp. 681–690.

- ^ "Opening Archaeological Museum of Castellammare di Stabia Libero D'Orsi". Pompeii Sites. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Gardelli, Paolo. Stabiae and the Beginning of European Archaeology: From Looting to Science. Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art: Collection of articles. Vol. 8. Ed. S. V. Mal’tseva, E. Iu. Staniukovich-Denisova, A. V. Zakharova. St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg Univ. Press, 2018, pp. 686

- ^ "Villa San Marco". Pompeii Sites. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Villa Arianna". Pompeii Sites. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Libero D'Orsi, Antonio Carosella; Vincenzo Cuccurullo, The excavations of Stabiae: excavation newspaper, Rome, Quasar, 1996, ISBN 88-7140-104-2

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia, Rome, Editori Laterza, 1982. p. 323

- ^ Giuseppe Di Massa, the territory of Gragnano in antiquity and the ager stabianus, pp. 1–48. http://www.centroculturalegragnano.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Il-Territorio-di-Gragnano-nell%E2%80%99antichit%C3%A0-e-l%E2%80%99Ager-Stabianus.pdf Archived 25 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Homepage – Pompeii Sites Portale Ufficiale Parco Archeologico di Pompei". Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio e Anna Maria Sodo, Stabia: storia e architettura: 250º anniversario degli scavi di Stabiae 1749-1999, Roma, L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2004, ISBN 978-88-826-5201-2. p 31

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompei, Ercolano, Stabia, Roma, Editori Laterza, 1982. p. 331

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompei, Ercolano, Stabia, Roma, Editori Laterza, 1982. p. 326

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio e Anna Maria Sodo, Stabia: storia e architettura: 250º anniversario degli scavi di Stabiae 1749-1999, Roma, L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2004, ISBN 978-88-826-5201-2. p. 30

- ^ "Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation | Onlus foundation".

- ^ Archemail 2006: The Peristyle of Villa San Marco in Stabiae (NA), The chronicle and photos of the discovery https://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_c?depth=1&hl=en&prev=search&rurl=translate.google.com&sl=it&sp=nmt4&u=https://web.archive.org/web/20131019153951/http://www.archemail.it/stabia1.htm&usg=ALkJrhht3E3d9Oh-fByku8_GrbJ_sk1_Bw

- ^ The 2012 Excavation Season at the Villa San Marco, Stabiae: Preliminary Field Report1 Taco T. Terpstra www.fastionline.org/docs/FOLDER-it-2013-286.pdf. Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179)

- ^ "Castellammare di Stabia, la sua vita dopo l'eruzione". turismo.it (in Italian). Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ M. Ruggiero: Degli Scavi di Stabiae dal 1749 al 1782, 1881

- ^ Pompeiisites.org

- ^ Taco T. Terpstra. The 2011 Field Season at the Villa San Marco, Stabiae: Preliminary Report on the Excavations, The Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179)

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio; Anna Maria Sodo, Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Cultura e archeologia da Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006. ISBN 88-8090-126-5 p. 26

- ^ "villa san marco stabiae p1". Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Antiquity Recovered: The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum, editor Victoria C. Coates Gardner, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007 ISBN 0892368721

- ^ Antonio Ferrara, Castellammare di Stabia – Short guide to the excavations of Stabiae, Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2005

- ^ Howe, Thomas N. A Most Fragile Art Object: Interpreting and Presenting the Strolling Garden of the Villa Arianna, Stabiae. In: Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art: Collection of articles. Vol. 8. Ed. S. V. Mal’tseva, E. Iu. Staniukovich-Denisova, A. V. Zakharova. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg Univ. Press, 2018, pp. 691–700ISSN 2312-2129.

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia, Rome, Editori Laterza, 1982. p. 315

- ^ "Archemail l'archeologia in Campania – Gruppo Archeologico Napoletano ONLUS – Il notiziario archeologico della Campania". Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ La Villa di Arianna http://www.comune.castellammare-di-stabia.napoli.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=511:la-villa-di-arianna&catid=70:siti-archeologici

- ^ "Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Valetudinarium". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio, Anna Maria Sodo, Stabiae – Archaeological Guide to Villas , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006, ISBN 88-8090-125-7

- ^ "Villa of Anteros and Hercules – AD79eruption". sites.google.com. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ PAOLA MINIERO: Ville scavate nel Settecento nel territorio di Stabiae, Città vesuviane: antichità e fortuna: il suburbio e l'agro di Pompei, Ercolano, Oplontis e Stabiae, Roma: Treccani editrice, 2015

- ^ Thesis: The rustic villa in Petraro nell'Ager stabianus, Andrea Paduano, 2015, University of Salerno

- ^ a b "Villa Petraro – AD79eruption". sites.google.com. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ A. Pesce, ed., In Stabiano (Castellammare di Stabia: Longobardi, 2005), 62

- ^ "Villa Petraro (Stabiae – Campania)". romanoimpero.com. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Villa Gragnano Localita Carmiano". pompeiiinpictures.com. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio; Anna Maria Sodo, Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Cultura e archeologia da Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, Longobardi Editore, 2006. ISBN 88-8090-126-5 p 36

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompei, Ercolano, Stabia , Roma, Editori Laterza, 1982. p 331

- ^ "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), APOTHE´CA". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompei, Ercolano, Stabia , Roma, Editori Laterza, 1982. p 330

- ^ "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), TORCULARIUM". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ a b Giuseppe Di Massa, Il Territorio di Gragnano nell'antichità e l'ager stabianus (PDF), pp. 41 http://www.centroculturalegragnano.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Il-Territorio-di-Gragnano-nell%E2%80%99antichit%C3%A0-e-l%E2%80%99Ager-Stabianus.pdf Archived 25 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Napoli, p. 347-8

- ^ Villa detto Carmiano in Masseria Buonodono https://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/VF/Villa_008%20Gragnano%20Carmiano%20masseria%20Buonodono.htm

- ^ Arnold De Vos; Mariette De Vos, Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia, Rome, Editori Laterza, 1982. p. 328

- ^ Giovanna Bonifacio, Anna Maria Sodo and Gina Carla Ascione, In Stabiano – Culture and Archeology from Stabiae , Castellammare di Stabia, p. 16. Longobardi Editore, 2006, ISBN 88-8090-126-5 p 18

External links

[edit]- Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation site

- Stabiae – Comprehensive site on the eruption of 79 AD Archived 27 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Herculaneum/Pompeii/Stabiae Website Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Video Villa San Marco

- Romano-Campanian Wall-Painting Archived 7 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Castellammare di Stabia

- Archaeological sites in Campania

- Coastal towns in Campania

- Destroyed populated places

- Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD

- Former populated places in Italy

- National museums of Italy

- Pompeii (ancient city)

- Populated places established in the 1st millennium BC

- Populated places disestablished in the 1st century

- Roman sites of Campania

- Roman towns and cities in Italy

- Tourist attractions in Campania