The Horseman on the Roof

| The Horseman on the Roof | |

|---|---|

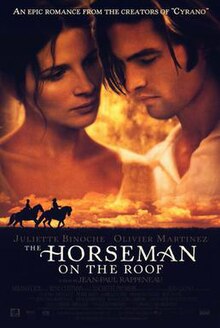

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jean-Paul Rappeneau |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Horseman on the Roof by Jean Giono |

| Produced by | Bernard Bouix |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Jacques Weber |

| Cinematography | Thierry Arbogast |

| Edited by | Noëlle Boisson |

| Music by | Jean-Claude Petit |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | AMLF |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $26,8 million[1] |

| Box office | $23,2 million[1] |

The Horseman on the Roof (French: Le hussard sur le toit) is a 1995 French film directed by Jean-Paul Rappeneau and starring Juliette Binoche and Olivier Martinez. Based on the 1951 French novel Le hussard sur le toit by Jean Giono, the film follows the adventures of a young Italian nobleman in France raising money for the Italian revolution against Austria during a time of cholera. The Italian struggle for independence and the cholera pandemic in southern France in 1832 are historical events. The film received César Awards in 1996 for Best Cinematography and Best Sound, as well as eight César Award nominations for Best Film, Best Costume Design, Best Actress, Best Director, Best Editing, Best Music, Best Production Design, and Most Promising Actress.

Plot

[edit]In July 1832, Italian patriots hiding out in Aix, France, are betrayed by one of their own, and Austrian agents are on their trail. One patriot, Giacomo, is dragged away and executed. His wife runs off to warn their friend, Angelo Pardi (Olivier Martinez), a young Italian nobleman in France raising money for the Italian revolution against Austrian Empire. As the agents descend on his apartment, Angelo escapes into the countryside.

At Meyrargues, Angelo looks for his compatriot and childhood friend, Maggionari, and then continues on to another village, where he writes to his mother, "Always fleeing. When can I fight and show what your son can do?" His mother purchased his commission as a colonel in the Piedmont Hussars, and he's never seen battle. Angelo encounters Maggionari, who turns out to be the traitor. When the Austrian agents arrive, Angelo fights them off and escapes.

The next day, Angelo enters a village ravaged by a cholera epidemic. The sight of the corpses abandoned to the scavenging crows sickens him. He meets a country physician, who shows him how to treat cholera victims by vigorously rubbing alcohol on the skin. Angelo continues north, passing a small village where corpses are being burned. He meets a young woman and two children and accompanies them to the outskirts of Manosque. The young woman, who is a tutor and lover of books, gives him a copy of Rinaldo and Armida as a parting gift.

While in Manosque, Angelo is captured by a paranoid mob who accuse him of poisoning the town fountain. He is taken to the authorities, who soon abandon their posts in fear. Angelo searches for a compatriot, but encounters the Austrian agents. Angelo eludes them, and with sword in hand, fights his way through the hysterical mob and escapes across the rooftops. From his refuge above the town, Angelo watches one of the agents chased down and beaten to death, and later watches the piles of corpses being burned in the night.

To escape the rain, Angelo enters a dwelling where he is discovered by Countess Pauline de Théus (Juliette Binoche). Apologizing for his presence, Angelo reassures her that he is a gentleman. Pauline offers him food and drink, and soon he falls asleep from exhaustion. The following morning, Pauline is gone and Angelo joins the forced evacuation of the town. In the hills outside Manosque, Angelo meets his compatriot, Giuseppe, who possesses money raised for the Italian resistance, but which cannot now be delivered because of the quarantine and roadblocks. Angelo agrees to deliver the money to Milan using backroads. Before leaving, he encounters the traitor, Maggionari, who attempts to kill Angelo before succumbing to cholera.

Angelo and Pauline meet again, and she joins him in a daring river escape. At Les Mées, rather than head east toward the Italian border, Angelo accompanies Pauline north toward her castle near Gap. Angelo insists it is his duty, so they set off through the countryside, avoiding the plague-ridden towns. Forced to camp out in the open, romantic feelings develop between the two, but Angelo remains gallant. Asked if he comes from a military family, Angelo reveals he never knew his father, saying, "He came to Italy with Napoleon, then left." Everything he learned in life came from his mother.

The next day, they travel to a heavily garrisoned village where they visit a friend of Pauline's husband and learn that he returned to Manosque to search for her. Determined to find her husband, Pauline leaves Angelo and rides off. Angelo follows, only to see her captured by the militia, who take her into quarantine at a convent. Knowing if she stays there she will die, Angelo surrenders to the militia in order to rescue her. Pauline understands he's risked his life again for her. Angelo orchestrates another daring escape by setting fire to the convent. Impressed by Angelo's bravery and intelligence, Pauline promises to trust the young Piedmont Hussard, saying, "I'll obey you like a soldier." Their mutual affection continues to grow as they make their way toward her castle at Théus.

As night descends, they seek shelter from the rain in a small abandoned mansion, where they warm themselves at the fireplace and drink wine. Pauline conveys her feelings for him, but Angelo remains a gentleman. Pauline recounts how she met her husband, forty years her senior. She was a sixteen-year-old country doctor's daughter when she found him near death with a bullet in his chest. Her father saved his life, and she tended to him for days, nursing him back to health. When he recovered, he left without revealing his identity, but six months later, he returned and asked for her hand in marriage—revealing he was a Count with extensive property.

Angelo prepares to leave, but Pauline decides to stay in the mansion for the night. As she climbs the staircase, she collapses showing symptoms of cholera. Angelo rushes her to the fireplace, rips the clothing from her body, and vigorously rubs alcohol on her skin—tending to her throughout the night trying to save her life. In the morning, Angelo is awakened by Pauline's frail but loving touch. Soon they are back on the road, completing the last few miles to Pauline's castle, where they are met by her husband, Count Laurent de Théus. Angelo leaves and returns to Italy to fight in the revolution.

One year later, Pauline returns to Aix where everything appears as it once was—but the cholera has taken a heavy toll. She looks for the house near the Bishop's Palace where Angelo stayed. She writes letters to Angelo, inquiring after his condition. Another year passes, and Pauline finally receives a letter from Angelo at the castle. She walks off alone to read it, while the Count watches from a window, knowing Angelo's memory would not fade. Pauline looks east towards the snow-covered Alps that separate her from Italy and Colonel Angelo Pardi, the young gallant officer who once saved her life.[2]

Cast

[edit]- Juliette Binoche as Pauline de Théus

- Olivier Martinez as Angelo Pardi

- Pierre Arditi as Monsieur Peyrolle

- François Cluzet as The Doctor

- Jean Yanne as Le Colporteur

- Claudio Amendola as Maggionari

- Isabelle Carré as The Tutor

- Carlo Cecchi as Giuseppe

- Christiane Cohendy as Madame Peyrolle

- Yolande Moreau as Madame Rigoard

- Daniel Russo as Monsieur Rigoard

- Paul Freeman as Laurent de Theus

- Richard Sammel as Franz

- Jean-Marie Winling as Alexandre Petit

- Nathalie Krebs as Madame Barthelemy

- Laura Marinoni as Carla

- Christophe Odent as Monsieur Barthelemy

- Hervé Pierre as Brig. Maugin

- Jacques Sereys as The Old Man

- Élisabeth Margoni as The Farmer's Wife

- Gérard Depardieu as The Inspector (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Principal photography began from 16 May 1994 to 17 November 1994. [3]

Filming locations

[edit]- Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (party at the beginning)

- Avignon, Vaucluse, France (exteriors)

- Beaucaire, Gard, France (procession scene)

- Châteauneuf-Miravail, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France (exteriors)

- Cucuron, Vaucluse, France (exteriors)

- Forcalquier, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France

- Fort des Têtes, Briançon, Hautes-Alpes, France (fort scenes)

- Gorges de la Méouge, Hautes-Alpes, France (exteriors)

- Manosque, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France

- Menthon-Saint-Bernard, Haute-Savoie, France (final castle scene)

- Montbonnot-Saint-Martin, Isère, France (final scene)

- Noyers-sur-Jabron, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France (chapel scene)

- Plateau des Fraches, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France

- Relais Saint-Pons, Aix-en-Provence, Bouches-du-Rhône, France (river where Giuseppe is executed)

- Saint-Albin-de-Vaulserre, Isère, France (castle scene)

- Saint-Pierre-Avez, Hautes-Alpes, France (exteriors)

- Saint-Vincent-sur-Jabron, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France (exteriors)

- Salérans, Hautes-Alpes, France (exteriors)

- Savournon, Hautes-Alpes, France (exteriors)

- Sisteron, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France (exteriors)

- Ventavon, Hautes-Alpes, France

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]In his review in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars, calling it "a rousing romantic epic about beautiful people having thrilling adventures in breathtaking landscapes." Ebert went on to write, "It's a grand entertainment, intelligently written, well-researched."[4]

In his review in The New York Times, Stephan Holden wrote, "The movie aspires to an epic grandeur that is at once sweepingly romantic and contemporary in the lightness of its touch. Although that goal proves elusive, the film will still leave you dazzled with its vision of a beautiful world cleft by disaster."[5]

In his review in Reel Views, James Berardinelli wrote, "This is a wonderful spectacle, and, with all the action and adventure, it's an undeniably enjoyable romp. Even those who typically shun France's more artistic fare will be entertained by this big-budget feature. Not counting the subtitles, it's the kind of thing that Hollywood would be proud of. There's nothing in this film that American audiences can't relate to."[6]

In his San Francisco Chronicle review, Peter Stack wrote, "The Horseman on the Roof is a lush, grandly designed film with an impossibly good-looking couple at its center. The romantic story is played out against some of France's most enchanting countryside."[7]

On the aggregate reviewer website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a 63% positive rating from critics based on 19 reviews.[8]

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| César Award, 1996 | Best Cinematography | Thierry Arbogast | Won |

| Best Sound | Pierre Gamet, Jean Goudier, Dominique Hennequin |

Won | |

| Best Actress | Juliette Binoche | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Franca Squarciapino | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Jean-Paul Rappeneau | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Noëlle Boisson | Nominated | |

| Best Film | Jean-Paul Rappeneau | Nominated | |

| Best Music Written for a Film | Jean-Claude Petit | Nominated | |

| Best Production Design | Jacques Rouxel, Ezio Frigerio, Christian Marti |

Nominated | |

| Most Promising Actress | Isabelle Carré | Nominated | |

| Nastro d'Argento, 1997 | Silver Ribbon for Best Costume Design | Franca Squarciapino | Won |

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Le hussard sur le toit". JP's Box Office. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Jean-Paul Rappeneau (Director) (2003). The Horseman on the Roof (DVD). New York City: Miramax. Archived from the original on 2019-03-08. Retrieved 2018-06-29.

- ^ "The Horseman on the Roof".

- ^ Ebert, Roger (May 24, 1996). "The Horseman on the Roof". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (May 17, 1996). "The Horseman on the Roof". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "The Horseman On the Roof". Reel Views. Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ Stack, Peter (May 24, 1996). "Horseman Delivers Headlong Gallic Dash". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ "The Horseman on the Roof". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 26 September 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1995 films

- 1990s French films

- 1990s French-language films

- 1990s historical adventure films

- 1990s Italian-language films

- 1995 multilingual films

- Films about infectious diseases

- Films based on works by Jean Giono

- Films directed by Jean-Paul Rappeneau

- Films scored by Jean-Claude Petit

- Films set in France

- Films set in the 1830s

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography César Award

- Films with screenplays by Jean-Claude Carrière

- Films with screenplays by Jean-Paul Rappeneau

- French adventure films

- French historical adventure films

- French multilingual films

- French romance films