Henri Rousseau

Henri Rousseau | |

|---|---|

Rousseau in 1907; photo by Dornac | |

| Born | Henri Julien Félix Rousseau 21 May 1844 Laval, France |

| Died | 2 September 1910 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Self-taught |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Sleeping Gypsy, Tiger in a Tropical Storm, The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope, Boy on the Rocks |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism, Naïve art, Primitivism |

| Signature | |

Henri Julien Félix Rousseau (French: [ɑ̃ʁi ʒyljɛ̃ feliks ʁuso]; 21 May 1844 – 2 September 1910)[1] was a French post-impressionist painter in the Naïve or Primitive manner.[2][3] He was also known as Le Douanier (the customs officer), a humorous description of his occupation as a toll and tax collector.[1] He started painting seriously in his early forties; by age 49, he retired from his job to work on his art full-time.[4]

Ridiculed during his lifetime by critics, he came to be recognized as a self-taught genius whose works are of high artistic quality.[5][6] Rousseau's work exerted an extensive influence on several generations of avant-garde artists.[4]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Rousseau was born in Laval, Mayenne, France, in 1844 into the family of a tinsmith; he was forced to work there as a young child.[7] He attended Laval High School as a day student, and then as a boarder after his father became a debtor and his parents had to leave the town upon the seizure of their house. Though mediocre in some of his high school subjects, Rousseau won prizes for drawing and music.[8]

After high school, he worked for a lawyer and studied law, but "attempted a small perjury and sought refuge in the army."[9] He served four years, starting in 1863. With his father's death, Rousseau moved to Paris in 1868 to support his widowed mother as a government employee.[citation needed]

In 1868, he married Clémence Boitard, his landlord's 15-year-old daughter, with whom he had six children (only one survived). In 1871, he was appointed as a collector of the octroi of Paris, collecting taxes on goods entering Paris. His wife died in 1888 and he married Josephine Noury in 1898.[citation needed]

Career

[edit]

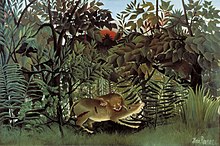

From 1886, he exhibited regularly in the Salon des Indépendants, and, although his work was not placed prominently, it drew an increasing following over the years. Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) was exhibited in 1891, and Rousseau received his first serious review when the young artist Félix Vallotton wrote: "His tiger surprising its prey ought not to be missed; it's the alpha and omega of painting." Yet it was more than a decade before Rousseau returned to depicting his vision of jungles.[4]

In 1893, Rousseau moved to a studio in Montparnasse where he lived and worked until his death in 1910.[10] In 1897, he produced one of his most famous paintings, La Bohémienne endormie (The Sleeping Gypsy).

In 1905, Rousseau's large jungle scene The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants near works by younger leading avant-garde artists such as Henri Matisse, in what is now seen as the first showing of The Fauves. Rousseau's painting may even have influenced the naming of the Fauves.[4]

In 1907, he was commissioned by artist Robert Delaunay's mother, Berthe, Comtesse de Delaunay, to paint The Snake Charmer.[citation needed]

Le Banquet Rousseau

[edit]When Pablo Picasso happened upon a painting by Rousseau being sold on the street as a canvas to be painted over, the younger artist instantly recognised Rousseau's genius and went to meet him. In 1908, Picasso held a half serious, half burlesque banquet in his studio at Le Bateau-Lavoir in Rousseau's honour.[1] Le Banquet Rousseau, "one of the most notable social events of the twentieth century," wrote American poet and literary critic John Malcolm Brinnin, "was neither an orgiastic occasion nor even an opulent one. Its subsequent fame grew from the fact that it was a colorful happening within a revolutionary art movement at a point of that movement's earliest success, and from the fact that it was attended by individuals whose separate influences radiated like spokes of creative light across the art world for generations."[11]

Guests at the banquet Rousseau included: Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Marie Laurencin, André Salmon, Maurice Raynal, Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, Leo Stein, and Gertrude Stein.[12]

Maurice Raynal, in Les Soirées de Paris, 15 January 1914, p. 69, wrote about "Le Banquet Rousseau".[13] Years later the French writer André Salmon recalled the setting of the illustrious banquet:

Here the nights of the Blue Period passed... here the days of the Rose Period flowered... here the Demoiselles d'Avignon halted in their dance to re-group themselves in accordance with the golden number and the secret of the fourth dimension... here fraternized the poets elevated by serious criticism into the School of the Rue Ravignan... here in these shadowy corridors lived the true worshippers of fire ... here one evening in the year 1908 unrolled the pageantry of the first and last banquet offered by his admirers to the painter Henri Rousseau called the Douanier.[11][12][14]

Retirement and death

[edit]After Rousseau's retirement in 1893, he supplemented his small pension with part-time jobs and work such as playing a violin in the streets. He also worked briefly at Le petit Journal, where he produced a number of its covers.[4]

An equally famous work by Rousseau, included in the collection of John Hay Whitney, is Tropical Forest with Monkeys, which was painted during the last months of his life. It shows one of his signature exotic landscapes, lush, tropical, and virgin. Many of the animals in Rousseau's images have human faces or attributes. The central monkeys in this painting hold green sticks from which strings appear to dangle, suggesting fishing poles and human leisure activities, thereby emphasizing the quasi-human experience of the animals. In this sense Rousseau's anthropomorphized primates can be seen not as true wild beasts, but rather as representing an escape from the "jungle" of Paris and the everyday grind of civilized life.[15]

Rousseau exhibited his final painting, The Dream, in March 1910, at the Salon des Independants.

In the same month Rousseau suffered a phlegmon in his leg, one which he ignored.[16] In August, when he was admitted to the Necker Hospital[17] in Paris where his son had died, he was found to have gangrene in his leg. After an operation, he died from a blood clot on 2 September 1910.

At his funeral, seven friends stood at his grave: the painters Paul Signac and Manuel Ortiz de Zárate; the artist couple Robert Delaunay and Sonia Terk; the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși; Rousseau's landlord Armand Queval, and Guillaume Apollinaire, who wrote the epitaph Brâncuși put on the tombstone:

We salute you Gentle Rousseau you can hear us.

Delaunay, his wife, Monsieur Queval and myself.

Let our luggage pass duty free through the gates of heaven.

We will bring you brushes paints and canvas.

That you may spend your sacred leisure in the

light and Truth of Painting.

As you once did my portrait facing the stars, lion and the gypsy.

Artistry

[edit]Paintings

[edit]

Rousseau claimed he had "no teacher other than nature",[3] although he admitted he had received "some advice" from two established Academic painters, Félix Auguste Clément and Jean-Léon Gérôme.[18] Essentially, he was self-taught and is considered to be a naïve or primitive painter.

His best-known paintings depict jungle scenes, even though he never left France or saw a jungle. Stories spread by admirers that his army service included the French expeditionary force to Mexico are unfounded. His inspiration came from illustrations in children's books[19] and the botanical gardens in Paris, as well as tableaux of taxidermy wild animals. During his term of service, he had also met soldiers who had survived the French expedition to Mexico, and he listened to their stories of the subtropical country they had encountered. To the critic Arsène Alexandre, he described his frequent visits to the Jardin des Plantes: "When I go into the glass houses and I see the strange plants of exotic lands, it seems to me that I enter into a dream."

Along with his exotic scenes there was a concurrent output of smaller topographical images of the city and its suburbs.

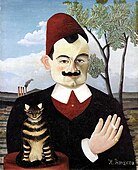

He claimed to have invented a new genre of portrait landscape, which he achieved by starting a painting with a specific view, such as a favourite part of the city, and then depicting a person in the foreground, most notably his early Myself, Portrait-Landscape (1890).

Criticism and recognition

[edit]Rousseau's flat, seemingly childish style was disparaged by many critics; people often were shocked by his work or ridiculed it.[6][20] His ingenuousness was extreme, and he always aspired, in vain, to conventional acceptance. Many observers commented that he painted like a child, but the work shows sophistication with his particular technique.[3][6]

Legacy

[edit]

Rousseau's work exerted an extensive influence on several generations of avant-garde artists, including Pablo Picasso, Jean Hugo, Fernand Léger Jean Metzinger, Max Beckmann, and the Surrealists. According to Roberta Smith, an art critic writing in The New York Times, "Beckmann’s amazing self-portraits, for example, descend from the brusque, concentrated forms of Rousseau’s portrait of the writer Pierre Loti."[4][21]

In 1911, a retrospective exhibition of Rousseau's works was shown at the Salon des Indépendants. His paintings were also shown at the first Blaue Reiter exhibition.[citation needed]

Critics have noted the influence of Rousseau on Wallace Stevens's poetry. See, for instance, Stevens's "Floral Decorations for Bananas" in the collection Harmonium.[citation needed]

The American poet Sylvia Plath was a great admirer of Rousseau, referencing his art, as well as drawing inspiration from his works in her poetry. The poem, "Yadwigha, on a Red Couch, Among Lilies" (1958), is based upon his painting, The Dream, whilst the poem "Snakecharmer" (1957) is based upon his painting The Snake Charmer.[22]

The song "The Jungle Line", by Joni Mitchell, is based upon a Rousseau painting.[23]

Underground comic artist Bill Griffith drew a four-page biographical sketch of Rousseau, A Couch in the Sun, which was included in issue #2 of the Arcade anthology.[citation needed]

The visual style of Michel Ocelot's 1998 animation film, Kirikou and the Sorceress, is partly inspired by Rousseau, particularly the depiction of the jungle vegetation.[24]

A Rousseau painting was used as an inspiration for the 2005 animated film Madagascar.[25]

Rousseau's 1908 painting Fight Between a Tiger and a Buffalo was used as the inspiration for a series of 2021 advertisements concerning the rebrand of Facebook into the metaverse company Meta.[26]

Exhibitions

[edit]Two major museum exhibitions of his work were held in 1984–85 (in Paris, at the Grand Palais; and in New York, at the Museum of Modern Art) and in 2001 (Tübingen, Germany). "These efforts countered the persona of the humble, oblivious naïf by detailing his assured single-mindedness and tracked the extensive influence his work exerted on several generations of vanguard artists," critic Roberta Smith wrote in a review of a later exhibition.[4]

A major exhibition of his work, "Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris", was shown at the Tate Modern from 3 November 2005 to 5 February 2006, organised by the Tate and the Musée d'Orsay, where the show also appeared. The exhibition, encompassing 48 of his paintings, was on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington from 16 July to 15 October 2006 and at the Grand Palais in Paris from 15 March to 19 June 2006.[27][28]

Gallery

[edit]-

A Carnival Evening, 1886, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA

-

Self Portrait, 1890, National Gallery Prague

-

Le Moulin (The Mill), c. 1896, Musée Maillol, Paris

-

Boy on the Rocks, 1895–1897, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897, MoMA, New York

-

La tour Eiffel peinte par Henri Rousseau, 1898, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

-

Self-portrait of the Artist with a Lamp, 1903

-

The Merry Jesters, 1906, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA

-

The Flamingoes, 1907, Private collection

-

The Snake Charmer, 1907, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

-

The Repast of the Lion, c.1907, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Exotic Landscape, 1908, Private collection

-

Fight Between a Tiger and a Buffalo, 1908, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

-

View of the Bridge in Sevres and the Hills of Clamart, Saint-Cloud and Bellevue with biplane, balloon and dirigible, 1908, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

-

In a Tropical Forest Combat of a Tiger and a Buffalo, 1908–1909, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

-

The Football Players, 1908, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Muse Inspiring the Poet (Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin), 1909, Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland

-

The Equatorial Jungle, 1909, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

Bouquet of Flowers, 1910, Tate Gallery, London

-

Pierre Loti, 1910, Kunsthaus Zürich, Switzerland

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Henri Rousseau biography Archived 24 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine at the Guggenheim

- ^ Artillerymen by Rousseau at the Guggenheim

- ^ a b c "Welcome to HenriRousseau.org – "Le Douanier" : The Life and Works of Henri Rousseau". Henrirousseau.org. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roberta Smith (14 July 2006) "Henri Rousseau: In imaginary jungles, a terrible beauty lurks" The New York Times. Accessed 14 July 2006

- ^ Rousseau at the National Gallery of Art

- ^ a b c Cornelia Stabenow (2001). Rousseau. Taschen. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-3-8228-1364-5.

- ^ Henri Rousseau biography, Princeton Archived 16 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Henri Rousseau, (1979), Dora Vallier

- ^ Karen Lee Spaulding (ed.) Masterworks at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, (1999), first published as 125 Masterpieces from the Collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (1987). Hudson Hills Press / Albright-Knox Art Gallery. p. 72. ISBN 978-1555951696

- ^ Tate Modern | Past Exhibitions | Henri Rousseau | Artistic Circle Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine at www.tate.org.uk

- ^ a b John Malcolm Brinnin, The Third Rose, Gertrude Stein and Her World, An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, Toronto, 1959

- ^ a b Richard R. Brettell; Chicago. Sara Lee Collection; Natalie Henderson Lee (1999). Monet to Moore: The Millennium Gift of Sara Lee Corporation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08134-3.

- ^ Ann Temkin (2012). Rousseau: The Dream. The Museum of Modern Art. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-87070-830-5.

- ^ Mark Antliff, Patricia Dee Leighten (2008) A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, University of Chicago Press

- ^ Rousseau, Henri (1910), Tropical Forest with Monkeys, retrieved 21 May 2024

- ^ Yann Le Pichon (1982) The World of Henri Rousseau. Phaidon Press Ltd. Oxford. ISBN 0-7148-2256-6

- ^ Werner Schmalenbach (2000). Henri Rousseau: Dreams of the Jungle. Prestel Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 3-7913-2409-8.

- ^ Cornelia Stabenow (2001). Rousseau. Taschen. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-3-8228-1364-5.

- ^ Shannon Porter (2015) Art History. (Symbolism, frame 57)

- ^ Henri Rousseau, 1844–1910 By Cornelia Stabenow page 10

- ^ Joann Moser (1985) "Pre-Cubist Works, 1904–1909" in Jean Metzinger in Retrospect. The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press. pp. 34, 35. ISBN 978-0874140385

- ^ "Sylvia Plath's artistic influences". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ The Jungle Line. jonimitchell.com

- ^ Michel Ocelot (25 August 2008). "Director's notes". Kirikou.net. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ^ Lisa Rosen (8 May 2005). "A jungle's classic roots: Capturing The Style For 'Madagascar' Meant Going Past The '50S To Artist Henri Rousseau". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "A Classic Painting Becomes a 3-D Music Video in Meta's Vision of the Metaverse". Muse by Clio. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Henri Rousseau". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Rousseau, Henri; Morris, Frances; Green, Christopher; Ireson, Nancy; Frèches-Thory, Claire (2006). Henri Rousseau: jungles in Paris. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-5699-5. OCLC 62741468.

Further reading

[edit]- Much of the information in this article was taken from Henri Rousseau Jungles in Paris, The Tate Gallery, pamphlet accompanying the 2005 exhibition.

- The Banquet Years, by Roger Shattuck (includes an extensive Rousseau essay)

- Henri Rousseau, 1979, Dora Vallier (general illustrated essay)

- Henri Rousseau, 1984, The Museum of Modern Art New York (essays by Roger Shattuck, Henri Béhar, Michel Hoog, Carolyn Lanchner, and William Rubin; includes excellent color plates and analysis)

External links

[edit]- Henrirousseau.org, 118 works by Henri Rousseau

- Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris, at the National Gallery of Art Archived 2 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Rousseau text written for young readers Brief introduction to the artist's life and art. Entry contains links to two large reproductions of Rousseau paintings in the National Gallery of Art, a 4th grade lesson relating Rousseau's paintings to ecology, and hands-on activities suitable for classroom or home study.

- Ten Dreams Galleries

- The Sleeping Gypsy in the MoMA Online Collection

- 1844 births

- 1910 deaths

- People from Laval, Mayenne

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- 20th-century French painters

- 20th-century French male artists

- French Post-impressionist painters

- Naïve painters

- Self-taught artists

- Burials at the Cimetière parisien de Bagneux

- 19th-century French male artists

- Deaths from thrombosis

- Deaths from surgical complications