Spotted hyena

| Spotted hyena Temporal range: ~Early Pleistocene-Present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| At Etosha National Park, Namibia | |

| Whooping recorded in Umfolozi Game Reserve, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Hyaenidae |

| Genus: | Crocuta |

| Species: | C. crocuta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crocuta crocuta (Erxleben, 1777)

| |

| |

| range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy[2]

| |

The spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), also known as the laughing hyena,[3] is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus Crocuta, native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUCN due to its widespread range and large numbers estimated between 27,000 and 47,000 individuals.[1] The species is, however, experiencing declines outside of protected areas due to habitat loss and poaching.[1] Populations of Crocuta, usually considered a subspecies of Crocuta crocuta, known as cave hyenas, roamed across Eurasia for at least one million years until the end of the Late Pleistocene.[4] The spotted hyena is the largest extant member of the Hyaenidae, and is further physically distinguished from other species by its vaguely bear-like build,[5] rounded ears,[6] less prominent mane, spotted pelt,[7] more dual-purposed dentition,[8] fewer nipples,[9] and pseudo-penis. It is the only placental mammalian species where females have a pseudo-penis and lack an external vaginal opening.[10]

The spotted hyena is the most social of the Carnivora in that it has the largest group sizes and most complex social behaviours.[11] Its social organisation is unlike that of any other carnivore, bearing closer resemblance to that of cercopithecine primates (baboons and macaques) with respect to group size, hierarchical structure, and frequency of social interaction among both kin and unrelated group-mates.[12] However, the social system of the spotted hyena is openly competitive rather than cooperative, with access to kills, mating opportunities and the time of dispersal for males depending on the ability to dominate other clan-members. Females provide only for their own cubs rather than assist each other, and males display no paternal care. Spotted hyena society is matriarchal; females are larger than males, and dominate them.[13]

The spotted hyena is a highly successful animal, being the most common large carnivore in Africa. Its success is due in part to its adaptability and opportunism; it is primarily a hunter but may also scavenge, with the capacity to eat and digest skin, bone and other animal waste. In functional terms, the spotted hyena makes the most efficient use of animal matter of all African carnivores.[14] The spotted hyena displays greater plasticity in its hunting and foraging behaviour than other African carnivores;[15] it hunts alone, in small parties of 2–5 individuals or in large groups. During a hunt, spotted hyenas often run through ungulate herds to select an individual to attack. Once selected, their prey is chased over a long distance, often several kilometres, at speeds of up to 60 kilometres per hour (37 mph).[16]

The spotted hyena has a long history of interaction with humanity; depictions of the species exist from the Upper Paleolithic period, with carvings and paintings from the Lascaux and Chauvet Caves.[17] The species has a largely negative reputation in both Western culture and African folklore. In the former, the species is mostly regarded as ugly and cowardly, while in the latter, it is viewed as greedy, gluttonous, stupid, and foolish, yet powerful and potentially dangerous. The majority of Western perceptions on the species can be found in the writings of Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, though in relatively unjudgmental form. Explicit, negative judgments occur in the Physiologus, where the animal is depicted as a hermaphrodite and grave-robber.[18] The IUCN's hyena specialist group identifies the spotted hyena's negative reputation as detrimental to the species' continued survival, both in captivity and the wild.[18][19]

Etymology and naming

[edit]The spotted hyena's scientific name Crocuta was once widely thought to be derived from the Latin loanword crocutus, which translates as 'saffron-coloured one', in reference to the animal's fur colour. This was proven to be incorrect, as the correct spelling of the loanword would have been Crocāta, and the word was never used in that sense by Graeco-Roman sources. Crocuta actually comes from the Ancient Greek word Κροκόττας (krokottas), which is derived from the Sanskrit koṭṭhâraka, which in turn originates from kroshṭuka (both of which were originally meant to signify the golden jackal). The earliest recorded mention of Κροκόττας is from Strabo's Geographica, where the animal is described as a mix of wolf and dog native to Ethiopia.[20]

From Classical antiquity until the Renaissance, the spotted and striped hyena were either assumed to be the same species, or distinguished purely on geographical, rather than physical, grounds. Hiob Ludolf, in his Historia aethiopica, was the first to clearly distinguish the Crocuta from Hyaena on account of physical and geographical grounds, though he never had any first hand experience of the species, having gotten his accounts from an Ethiopian intermediary.[3] Confusion still persisted over the exact taxonomic nature of the hyena family in general, with most European travelers in Ethiopia referring to hyenas as "wolves". This partly stems from the Amharic word for hyena, ጅብ (jɨbb), which is linked to the Arabic word ذئب (dhiʾb) 'wolf'.[22]

The first detailed first-hand descriptions of the spotted hyena by Europeans come from Willem Bosman and Peter Kolbe. Bosman, a Dutch tradesman who worked for the Dutch West India Company at the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) from 1688 to 1701, wrote of Jakhals, of Boshond (jackals or woodland dogs) whose physical descriptions match the spotted hyena. Kolben, a German mathematician and astronomer who worked for the Dutch East India Company in the Cape of Good Hope from 1705 to 1713, described the spotted hyena in great detail, but referred to it as a "tigerwolf", because the settlers in southern Africa did not know of hyenas, and thus labelled them as "wolves".[23]

Bosman and Kolben's descriptions went largely unnoticed until 1771, when the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant used the descriptions and his personal experience with a captive specimen as a basis for consistently differentiating the spotted hyena from the striped in his Synopsis of Quadrupeds. The description given by Pennant was precise enough to be included by Johann Erxleben in his Systema regni animalis by simply translating Pennant's text into Latin. Crocuta was finally recognised as a separate genus from Hyaena in 1828.[24]

Taxonomy, origins and evolution

[edit]

Unlike the striped hyena, for which a number of subspecies were proposed in light of its extensive modern range, the spotted hyena is a genuinely variable species, both temporally and spatially. Its range once encompassed almost all of Africa and Eurasia, and displayed a large degree of morphological geographic variation, which led to an equally extensive set of specific and subspecific epithets. It was gradually realised that all of this variation could be applied to individual differences in a single subspecies. In 1939, biologist L Harrison Matthews demonstrated through comparisons between a large selection of spotted hyena skulls from Tanzania that all the variation seen in the then recognised subspecies could also be found in a single population, with the only set of characters standing out being pelage (which is subject to a high degree of individual variation) and size (which is subject to Bergmann's Rule). When fossils are taken into consideration, the species displayed even greater variation than it does in modern times, and a number of these named fossil species have since been classed as synonymous with Crocuta crocuta, with firm evidence of there being more than one species within the genus Crocuta still lacking.[25]

The ancestors of the genus Crocuta diverged from Hyaena (the genus of striped and brown hyenas) 10 million years ago.[26][27] The ancestors of the spotted hyena probably developed social behaviours in response to increased pressure from other predators on carcasses, which forced them to operate in teams. At one point in their evolution, spotted hyenas developed sharp carnassials behind their crushing premolars; this rendered waiting for their prey to die no longer a necessity, as is the case for brown and striped hyenas, and thus they became pack hunters as well as scavengers. They began forming increasingly larger territories, necessitated by the fact that their prey was often migratory and long chases in a small territory would have caused them to encroach into another clan's land.[8] It has been theorised that female dominance in spotted hyena clans could be an adaptation in order to successfully compete with males on kills, and thus ensure that enough milk is produced for their cubs.[13] Another theory is that it is an adaptation to the length of time it takes for cubs to develop their massive skulls and jaws, thus necessitating greater attention and dominating behaviours from females.[28]

Both Björn Kurtén and Camille Arambourg promoted an Asiatic origin for the species; Kurtén focussed his arguments on the Plio-Pleistocene taxon Crocuta sivalensis from the Siwaliks,[29] a view defended by Arambourg, who nonetheless allowed the possibility of an Indo-Ethiopian origin.[30] This stance was contested by Ficarelli and Torre, who referred to evidence of the spotted hyena's presence from African deposits dating from the early Pleistocene, a similar age to the Asian C. sivalensis.[31] Modern scholarship supports an African origin for the genus, with the earliest fossils of the genus Crocuta dating to the early Pliocene of Africa, around 3.63 to 3.85 million years ago.[32]

The earliest known fossil record of Crocuta crocuta in Africa is from the Cradle of Humankind, specifically from the Sterkfontein Member 4 which is dated approximately 2.1 million years ago in minimum, and it is also common in deposits dated between 2 to 1.5 million years ago.[33] Analysis of the mitochondrial genomes of Eurasian Crocuta (cave hyena) specimens shows no clear separation from African lineages. It also suggests that modern spotted hyena populations descend from a widely ranging Afro-Eurasian population that was only recently reduced in range to Africa exclusively.[34] However, analysis of the full nuclear genome suggests that Late Pleistocene African and Eurasian Crocuta populations were largely separate, having estimated to have diverged from each other around 2.5 million years ago, closely corresponding to the age of the earliest Crocuta specimens in Eurasia, which are around 2 million years ago from China. The nuclear genome results also suggest that the European and Asian populations were distinct from each other, but were more closely related to each other overall than to African Crocuta populations. Analysis of the nuclear genome suggests that there had been interbreeding between African and Eurasian populations for some time after the split, which likely explains the discordance between the nuclear and mitochondrial genome results, with the mitochondrial genomes of African and European Crocuta more closely related to each other than to Asian Crocuta, suggesting gene flow between the two groups after the split between the Asian and European populations.[32]

Its appearance in Europe and China coincided with the decline and eventual extinction of Pachycrocuta brevirostris, the giant short-faced hyena. As there is no evidence of environmental change being responsible, it is likely that the giant short-faced hyena became extinct due to competition with the spotted hyena.[35]

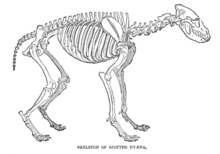

Description

[edit]Anatomy

[edit]

The spotted hyena has a strong and well-developed neck and forequarters, but relatively underdeveloped hindquarters. The rump is rounded rather than angular, which prevents attackers coming from behind from getting a firm grip on it.[36] The head is wide and flat with a blunt muzzle and broad rhinarium. In contrast to the striped hyena, the ears of the spotted hyena are rounded rather than pointed. Each foot has four digits, which are webbed and have short, stout and blunt claws. The paw-pads are broad and flat, with the whole undersurface of the foot around them being naked. The tail is relatively short, being 300–350 mm (12–14 in) long,[6] and resembles a pompom in appearance.[5] Unusually among hyaenids, and mammals in general, the female spotted hyena is considerably larger than the male.[37] Both sexes have a pair of anal glands which open into the rectum just inside the anal opening. These glands produce a white, creamy secretion which is pasted onto grass stalks by everting the rectum. The odour of this secretion is strong, smelling of boiling cheap soap or burning, and can be detected by humans several metres downwind.[38] The spotted hyena has a proportionately large heart, constituting close to 1% of its body weight, thus giving it great endurance in long chases. In contrast, a lion's heart makes up only 0.45–0.57 percent of its body weight.[39] The now extinct Eurasian populations were distinguished from the modern African populations by their shorter distal extremities and longer humerus and femur.[40]

The skull of the spotted hyena differs from that of the striped hyena by its much greater size and narrower sagittal crest. For its size, the spotted hyena has one of the most powerfully built skulls among the Carnivora.[41] The dentition is more dual purposed than that of other modern hyena species, which are mostly scavengers; the upper and lower third premolars are conical bone-crushers, with a third bone-holding cone jutting from the lower fourth premolar. The spotted hyena also has its carnassials situated behind its bone-crushing premolars, the position of which allows it to crush bone with its premolars without blunting the carnassials.[8] Combined with large jaw muscles and a special vaulting to protect the skull against large forces, these characteristics give the spotted hyena a powerful bite which can exert a pressure of 80 kgf/cm2 (1140 lbf/in²),[42] which is 40% more force than a leopard can generate.[43] The jaws of the spotted hyena outmatch those of the brown bear in bone-crushing ability,[44] and free ranging hyenas have been observed to crack open the long bones of giraffes measuring 7 cm in diameter.[45] A 63.1 kg (139 lb) spotted hyena is estimated to have a bite force of 565.7 newtons at the canine tip and 985.5 newtons at the carnassial eocene.[46] One individual in a study was found to exert a bite force of 4,500 newtons on the measuring instruments.[47]

Dimensions

[edit]The spotted hyena is the largest extant member of the Hyaenidae.[48] Adults measure 95–165.8 cm (37.4–65.3 in) in body length, and have a shoulder height of 70–91.5 cm (27.6–36.0 in).[49] Adult male spotted hyenas in the Serengeti weigh 40.5–55.0 kg (89.3–121.3 lb), while females weigh 44.5–63.9 kg (98–141 lb). Spotted hyenas in Zambia tend to be heavier, with males weighing on average 67.6 kg (149 lb), and females 69.2 kg (153 lb).[37] Exceptionally large weights of 81.7 kg (180 lb)[8] and 90 kg (200 lb)[49] are known. It has been estimated that adult members of the now extinct Eurasian populations weighed 102 kg (225 lb).[50]

Fur

[edit]Fur colour varies greatly and changes with age.[36] Unlike the fur of the striped and brown hyena, that of the spotted hyena consists of spots rather than stripes and is much shorter, lacking the well defined spinal mane of the former two species.[7] The base colour generally is a pale greyish-brown or yellowish-grey on which an irregular pattern of roundish spots is superimposed on the back and hind quarters. The spots, which are of variable distinction, may be reddish, deep brown or almost blackish. The spots vary in size, even on single individuals, but are commonly 20 mm (0.79 in) in diameter. A less distinct spot pattern is present on the legs and belly but not on the throat and chest. Some research groups (such as Ngorongoro Crater Hyena Project[51] and MSU Hyena Project[52]) often use the spot patterns to help identify individual hyenas. A set of five, pale and barely distinct bands replace the spots on the back and sides of the neck. A broad, medial band is present on the back of the neck, and is lengthened into a forward facing crest. The crest is mostly reddish-brown in colour. The crown and upper part of the face is brownish, save for a white band above both eyes, though the front of the eyes, the area around the rhinarium, the lips and the back portion of the chin are all blackish. The limbs are spotted, though the feet vary in colour, from light brown to blackish. The fur is relatively sparse and consists of two hair types; moderately fine underfur (measuring 15–20 mm (0.59–0.79 in)) and long, stout bristle hairs (30–40 mm (1.2–1.6 in)).[6] European Paleolithic rock art depicting the species indicates that the Eurasian populations retained the spots of their modern-day African counterparts.[17]

Female genitalia

[edit]

The genitalia of the female closely resembles that of the male; the clitoris is shaped and positioned like a penis, a pseudo-penis, and is capable of erection. The female also possesses no external vagina (vaginal opening), as the labia are fused to form a pseudo-scrotum. The pseudo-penis is traversed to its tip by a central urogenital canal, through which the female urinates, copulates and gives birth.[54][55] The pseudo-penis can be distinguished from the males' genitalia by its somewhat shorter length, greater thickness, and more rounded glans.[10][56][57] In both males and females, the base of the glans is covered with penile spines.[58][59] The formation of the pseudo-penis appears largely androgen independent, as the pseudo-penis appears in the female fetus before differentiation of the fetal ovary and adrenal gland.[10] When flaccid, the pseudo-penis is retracted into the abdomen, and only the prepuce is visible. After giving birth, the pseudo-penis is stretched, and loses many of its original aspects; it becomes a slack-walled and reduced prepuce with an enlarged orifice with split lips.[41]

Behaviour

[edit]Social behaviour

[edit]Spotted hyenas are social animals that live in large communities (referred to as "clans") which can consist of at most 80 individuals.[60] Group-size varies geographically; in the Serengeti, where prey is migratory, clans are smaller than those in the Ngorongoro Crater, where prey is sedentary.[61] Spotted hyena clans are more compact and unified than wolf packs, but are not as closely knit as those of African wild dogs.[62]

Females usually dominate males, including in cases where low-ranking females generally dominate over high-ranking males, but they will also occasionally co-dominate with a male.[63] There have also been cases in which a clan has been led by a male rather than a female.[64] Cubs take the rank directly below their mothers at birth. So when the matriarch passes away (or, in rare instances, disperses into another clan[65]), their youngest female cub will take over as matriarch. It is typical for females to remain with their natal clan, thus large clans usually contain several matrilines, whereas males typically disperse from their natal clan at the age of 2½ years. Höner et al. say that when a male co-dominates with a female or is otherwise able to lead, this is because the male was born to the matriarch of the clan and has taken the rank directly below his mother.[63][66]

The clan is a fission–fusion society, in which clan-members do not often remain together, but may forage in small groups.[67] High-ranking hyenas maintain their position through aggression directed against lower-ranking clan-members.[9] Spotted hyena hierarchy is nepotistic; the offspring of dominant females automatically outrank adult females subordinate to their mother.[68] However, rank in spotted hyena cubs is greatly dependent on the presence of the mother; low-ranking adults may act aggressively toward higher-ranking cubs when the mother is absent. Although individual spotted hyenas only care for their own young, and males take no part in raising their young, cubs are able to identify relatives as distantly related as great-aunts. Also, males associate more closely with their own daughters rather than unrelated cubs, and the latter favor their fathers by acting less aggressively toward them.[12]

Spotted hyena societies are more complex than those of other carnivorous mammals, and are remarkably similar to those of cercopithecine primates in respect to group size, structure, competition and cooperation. Like cercopithecine primates, spotted hyenas use multiple sensory modalities, recognise individual conspecifics, are conscious that some clan-mates may be more reliable than others, recognise third-party kin and rank relationships among clan-mates, and adaptively use this knowledge during social decision making. Also, like cercopithecine primates, dominance ranks in hyena societies are not correlated with size or aggression, but with ally networks.[9][12] In this latter trait, the spotted hyena further show parallels with primates by acquiring rank through coalition. However, rank reversals and overthrows in spotted hyena clans are rare.[9] The social network dynamics of spotted hyenas are determined by multiple factors.[69] Environmental factors include rainfall and prey abundance; individual factors include preference to bond with females and with kin; and topological effects include the tendency to close triads in the network. Female hyenas are more flexible than males in their social bonding preferences.[69] Higher ranking adult spotted hyenas tend to have higher telomere length and higher levels of some immune defense proteins in their blood serum.[70][71]

Territory size is highly variable, ranging from less than 40 km2 in the Ngorongoro Crater to over 1,000 km2 in the Kalahari. Home ranges are defended through vocal displays, scent marking and boundary patrols.[67] Clans mark their territories by either pasting or pawing in special latrines located on clan range boundaries. Spotted hyenas use scent gland secretions to distinguish between members of their own clan and members of neighboring clans. Within the same clan, differences in scent gland compositions can help individuals differentiate the reproductive states and sex of their members. One study analyzed the scent gland secretions of several hyenas belonging to three different clans and discovered a high degree of similarity in fatty acid composition among members of the same clans, while hyenas of different clans had more dissimilar scent gland secretions.[72] Further studies have proposed a symbiotic relationship between spotted hyenas and their scent gland bacteria, where the differences in fatty acids can be attributed to fermentation by different microbes.[73] Clan boundaries are usually respected; hyenas chasing prey have been observed to stop dead in their tracks once their prey crosses into another clan's range. Hyenas will however ignore clan boundaries in times of food shortage. Males are more likely to enter another clan's territory than females are, as they are less attached to their natal group and will leave it when in search of a mate. Hyenas travelling in another clan's home range typically exhibit bodily postures associated with fear, particularly when meeting other hyenas. An intruder can be accepted into another clan after a long period of time if it persists in wandering into the clan's territory, dens or kills.[74]

Mating, reproduction, and development

[edit]The spotted hyena is a non-seasonal breeder, though a birth peak does occur during the wet season. Females are polyestrous, with an estrus period lasting two weeks.[75] Like many feliform species, the spotted hyena is promiscuous, and no enduring pair bonds are formed. Members of both sexes may copulate with several mates over the course of several years.[55] Males will show submissive behaviour when approaching females in heat, even if the male outweighs his partner.[76] Females usually favour younger males born or joined into the clan after they were born. Older females show a similar preference, with the addition of preferring males with whom they have had long and friendly prior relationships.[77] Passive males tend to have greater success in courting females than aggressive ones.[78] Copulation in spotted hyenas is a relatively short affair,[76] lasting 4–12 minutes,[59] and typically only occurs at night with no other hyenas present.[76] The mating process is complicated, as the male's penis enters and exits the female's reproductive tract through her pseudo-penis rather than directly through the vagina, which is blocked by the false scrotum and testes. These unusual traits make mating more laborious for the male than in other mammals, and also make forced copulation physically impossible.[54][55] The female retracts her clitoris before the male's penis enters it by sliding beneath it, an operation facilitated by the penis's upward angle. The hyenas then adopt a typical mammalian mating posture[55][79] and usually lick their genitals for several minutes after mating.[80] Copulation may be repeated multiple times during a period of several hours.[55]

The length of the gestation period tends to vary greatly, but the average length is 110 days.[75] In the final stages of pregnancy, dominant females provide their developing offspring with higher androgen levels than lower-ranking mothers do. The higher androgen levels – the result of high concentrations of ovarian androstenedione – are thought to be responsible for the extreme masculinization of female behavior and morphology.[81] This has the effect of rendering the cubs of dominant females more aggressive and sexually active than those of lower ranking hyenas; high ranking male cubs will attempt to mount females earlier than lower ranking males.[82] The average litter consists of two cubs, with three occasionally being reported.[75] Males take no part in the raising of young.[83] Giving birth is difficult for female hyenas, as the females give birth through their narrow clitoris, and spotted hyena cubs are the largest carnivoran young relative to their mothers' weight.[84] During parturition, the clitoris ruptures to facilitate the passage of the young, and may take weeks to heal.[67]

Cubs are born with soft, dark brown hair, and weigh 1.5 kg on average.[85] Unique among carnivorous mammals, spotted hyenas are also born with their eyes open and with 6–7 mm long canine teeth and 4 mm long incisors. Also, cubs will attack each other shortly after birth. This is particularly apparent in same sexed litters, and can result in the death of the weaker cub.[84] This neonatal siblicide kills an estimated 25% of all hyenas in their first month. Male cubs which survive grow faster and are likelier to achieve reproductive dominance, while female survivors eliminate rivals for dominance in their natal clan.[79] Lactating females can carry 3–4 kg (6.6–8.8 lb) of milk in their udders.[68] Spotted hyena milk has the highest protein and fat content of any terrestrial carnivore.[67][86] Cubs will nurse from their mother for 12–16 months, though they can process solid food as early as three months.[87] Mothers do not regurgitate food for their young.[88] Females are protective of their cubs, and will not tolerate other adults, particularly males, approaching them. Spotted hyenas exhibit adult behaviours early in life; cubs have been observed to ritually sniff each other and mark their living space before the age of one month. Within ten days of birth, they are able to move at considerable speed. Cubs begin to lose the black coat and develop the spotted, lighter coloured pelage of the adults at 2–3 months. They begin to exhibit hunting behaviours at the age of eight months, and will begin fully participating in group hunts after their first year.[87] Spotted hyenas reach sexual maturity at the age of three years. The average lifespan in zoos is 12 years, with a maximum of 25 years.[89]

Denning behaviour

[edit]

The clan's social life revolves around a communal den. While some clans may use particular den sites for years, others may use several different dens within a year or several den sites simultaneously.[67] Spotted hyena dens can have more than a dozen entrances, and are mostly located on flat ground. The tunnels are usually oval in section, being wider than they are high, and narrow down from an entrance width of ½–1 metre (1.6–7.7 ft) to as small as 25 cm (9.8 in). In the rocky areas of East Africa and Congo, spotted hyenas use caves as dens, while those in the Serengeti use kopjes as resting areas in daylight hours. Dens have large bare patches around their entrances, where hyenas move or lie down on. Because of their size, adult hyenas are incapable of using the full extent of their burrows, as most tunnels are dug by cubs or smaller animals. The structure of the den, consisting of small underground channels, is likely an effective anti-predator device which protects cubs from predation during the absence of the mother. Spotted hyenas rarely dig their own dens, having been observed for the most part to use the abandoned burrows of warthogs, springhares and jackals. Faeces are usually deposited 20 metres (66 feet) away from the den, though they urinate wherever they happen to be. Dens are used mostly by several females at once, and it is not uncommon to see up to 20 cubs at a single site.[90] The general form of a spotted hyena den is tunnel-shaped, with a spacious end chamber used for sleeping or breeding. This chamber measures up to 2 metres (6.6 feet) in width, the height being rather less.[91] Females generally give birth at the communal den or a private birth den. The latter is primarily used by low status females to maintain continual access to their cubs, as well as ensure that they become acquainted with their cubs before transferral to the communal den.[67]

Intelligence

[edit]Compared to other hyenas, the spotted hyena shows a greater relative amount of frontal cortex which is involved in the mediation of social behavior. Studies strongly suggest convergent evolution in spotted hyena and primate intelligence.[12] A study done by evolutionary anthropologists demonstrated that spotted hyenas outperform chimpanzees on cooperative problem-solving tests; captive pairs of spotted hyenas were challenged to tug two ropes in unison to earn a food reward, successfully cooperating and learning the maneuvers quickly without prior training. Experienced hyenas even helped inexperienced clan-mates to solve the problem. In contrast, chimps and other primates often require extensive training, and cooperation between individuals is not always as easy for them.[92] The intelligence of the spotted hyena was attested to by Dutch colonists in 19th-century South Africa, who noted that hyenas were exceedingly cunning and suspicious, particularly after successfully escaping from traps.[93] Spotted hyenas seem to plan on hunting specific species in advance; hyenas have been observed to engage in activities such as scent marking before setting off to hunt zebras, a behaviour which does not occur when they target other prey species.[94] One of the signs of social intelligence is the ability to have a keen olfactory sense or nasal recognition. Spotted hyenas have unique scent signatures that help them distinguish themselves from other clans and/or individuals (i.e., males or females conspecific), which enables them to mark their territories with secretions from their scent glands.[95] Also, spotted hyenas have been recorded to utilise deceptive behaviour, including giving alarm calls during feeding when no enemies are present, thus frightening off other hyenas and allowing them to temporarily eat in peace. Similarly, mothers will emit alarm calls when attempting to interrupt attacks on their cubs by other hyenas.[12]

Responses to stress

[edit]Spotted hyenas are a good subject for studying the causes and consequences of stress because of the behavioral plasticity they exhibit to respond to their variable and unpredictable environment [96]. The hormonal and behavioral responses of spotted hyenas to a variety of stressful stimuli can shed light on how they will adapt in the future and how other gregarious, group-living species may respond to similar stressors [96][97].

Stress responses are often measured using corticosteroid levels non-invasively in hyenas, through the analysis of fecal or salivary glucocorticoid samples [98]. While corticosteroids typically fluctuate in predictable patterns across life-history states, spotted hyenas exhibit hormonal and corresponding behavioral responses to unpredictable social, environmental, and anthropogenic stressors [96].

Social stress

Aggression, social stability, and social connectedness play an important role in reinforcing hierarchies in spotted hyena clans, and social interactions can modulate stress levels [98][99]. In particular, being the target of aggression or experiencing social instability impose stress on spotted hyenas [98][100]. Exhibiting aggression, or experiencing social connectedness as juveniles can both immediately decrease stress, and reduce stress during later-life stages [98][101].

Environmental stress

Reductions in food and available foraging environments cause significant stress in wild spotted hyenas [100]. These challenges are exasperated by the increased unpredictability of migratory patterns in hyena prey resulting from climate related changes in the lengths of wet and dry seasons [102]. Spotted hyenas are responding by foraging over longer distances, which increases energy expenditure, and consequently the stress associated with lactation for nursing females [100]. Increased foraging range also invokes social stress from encroaching on other hyena clans' territories in search of prey [96][100].

Anthropogenic stress

While spotted hyenas typically show a range of innovative behavior, such as hiding in vegetative cover to avoid cattle herders, that help them cope with unpredictable environments, innovation is less common in urban swelling hyenas [97][100][103][104]. The consequences of this reduction in innovative behavior are not clear, though innovative behavior can modulate fitness trade-offs, like increased reproductive success with decreased offspring survival, in spotted hyenas [105].

Ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]

The spotted hyena is the most carnivorous member of the Hyaenidae.[13] Unlike its brown and striped cousins, the spotted hyena is primarily a predator; this has been shown since the 1960s.[106] One of the earliest studies to demonstrate their hunting abilities was done by wildlife ecologist Hans Kruuk, and he showed through a 7-year study of hyena populations in the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater that spotted hyenas hunt as much as lions, with later studies showing this tendency in many other areas of Africa. There are however large differences between populations, depending on their habitat, available prey species and the presence of other predators.[107] Thus the estimated contribution from hunting to their diet ranges from at least half up to 98%, the remainder being from scavenging.[108]

Wildebeest are the most commonly taken medium-sized ungulate prey item in both Ngorongoro and the Serengeti, with zebra and Thomson's gazelles, coming close behind.[109] Cape buffalo are rarely attacked due to differences in habitat preference, though adult bulls have been recorded to be taken on occasion.[110] In Kruger National Park, blue wildebeest, cape buffalo, plains zebra, greater kudu and impala are the spotted hyena's most important prey, while giraffe, impala, wildebeest and zebra are its major food sources in the nearby Timbavati area. Springbok and kudu are the main prey in Namibia's Etosha National Park, and springbok in the Namib. In the southern Kalahari, gemsbok, common eland, lechwe, waterbuck, wildebeest and springbok are the principal prey. In Chobe, the spotted hyena's primary prey consists of migratory zebra and resident impala. In Kenya's Masai Mara, 80% of the spotted hyena's prey consists of topi and Thomson's gazelle, save for during the four-month period when zebra and wildebeest herds migrate to the area. Bushbuck, suni and buffalo are the dominant prey items in the Aberdare Mountains, while Grant's gazelle, gerenuk, sheep, goats and cattle are likely preyed upon in northern Kenya.

Unlike other large African carnivores, spotted hyenas do not preferentially prey on any species, and only African buffalo and giraffe are significantly avoided. Spotted hyenas prefer prey with a body mass range of 56–182 kg (123–401 lb), with a mode of 102 kg (225 lb).[111] When hunting medium to large sized prey, spotted hyenas tend to select certain categories of animal; young animals are frequently targeted, as are old ones, though the latter category is not so significant when hunting zebras, due to their aggressive anti-predator behaviours.[112] Small prey is killed by being shaken in the mouth, while large prey is eaten alive.[113]

Enemies and competitors

[edit]Lions

[edit]

Where spotted hyenas and lions occupy the same geographic area, the two species occupy the same ecological niche, and are thus in direct competition with one another. In some cases, the extent of dietary overlap can be as high as 68.8%.[111] Lions typically ignore spotted hyenas, unless they are on a kill or are being harassed by them. There exists a common misconception that hyenas steal kills from lions, but most often it is the other way around,[114] and lions will readily steal the kills of spotted hyenas. In the Ngorongoro Crater, it is common for lions to subsist largely on kills stolen from hyenas. Lions are quick to follow the calls of hyenas feeding, a fact demonstrated by field experiments, during which lions repeatedly approached whenever the tape-recorded calls of hyenas feeding were played.[115]

When confronted on a kill by lions, spotted hyenas will either leave or wait patiently at a distance of 30–100 metres until the lions have finished eating.[116] In some cases, spotted hyenas are bold enough to feed alongside lions, and may occasionally force lions off a kill.[117] This mostly occurs during the nighttime, when hyenas are bolder.[118] Spotted hyenas usually prevail against groups of lionesses unaccompanied by males if they outnumber them 4:1.[119] In some instances they were seen to have taken on and routed two pride males while outnumbering them 5:1.[120]

The two species may act aggressively toward one another even when there is no food at stake.[118] Lions may charge at hyenas and maul them for no apparent reason; one male lion was filmed killing two hyenas on separate occasions without eating them,[121] and lion predation can account for up to 71% of hyena deaths in Etosha. Spotted hyenas have adapted to this pressure by frequently mobbing lions which enter their territories.[122] Experiments on captive spotted hyenas revealed that specimens with no prior experience with lions act indifferently to the sight of them, but will react fearfully to the scent.[123]

Other felids

[edit]Although cheetahs and leopards preferentially prey on smaller animals than those hunted by spotted hyenas, hyenas will steal their kills when the opportunity presents itself. Cheetahs are usually easily intimidated by hyenas, and put up little resistance,[124] while leopards, particularly males, may stand up to hyenas. There are records of some male leopards preying on hyenas.[125] Hyenas are nonetheless dangerous opponents for leopards; there is at least one record of a young adult male leopard dying from a sepsis infection caused by wounds inflicted by a spotted hyena.[126]

Canids

[edit]

Spotted hyenas will follow packs of African wild dogs to appropriate their kills. They will typically inspect areas where wild dogs have rested and eat any food remains they find. When approaching wild dogs at a kill, solitary hyenas will approach cautiously and attempt to take off with a piece of meat unnoticed, though they may be mobbed by the dogs in the attempt. When operating in groups, spotted hyenas are more successful in pirating dog kills, though the dog's greater tendency to assist each other puts them at an advantage against spotted hyenas, who rarely work in unison. Cases of dogs scavenging from spotted hyenas are rare. Although wild dog packs can easily repel solitary hyenas, on the whole, the relationship between the two species is a one sided benefit for the hyenas,[127] with wild dog densities being negatively correlated with high hyena populations.[128]

Medium-sized canids like Black-backed and side-striped jackals, and African wolves will feed alongside hyenas, though they will be chased if they approach too closely. Spotted hyenas will sometimes follow jackals and wolves during the gazelle fawning season, as jackals and wolves are effective at tracking and catching young animals. Hyenas do not take to eating wolf flesh readily; four hyenas were reported to take half an hour in eating a golden wolf. Overall, the two animals typically ignore each other when there is no food or young at stake.[129]

Other competitors

[edit]Spotted hyenas dominate other hyena species wherever their ranges overlap. Brown hyenas encounter spotted hyenas in the Kalahari, where the brown outnumber the spotted. The two species typically encounter each other on carcasses, which the larger spotted species usually appropriate. Sometimes, brown hyenas will stand their ground and raise their manes while emitting growls. This usually has the effect of seemingly confusing spotted hyenas, which will act bewildered, though they will occasionally attack and maul their smaller cousins. Similar interactions have been recorded between spotted and striped hyenas in the Serengeti.[130]

Though they readily take to water to catch and store prey, spotted hyenas will avoid crocodile-inhabited waters,[131] and usually keep a safe distance from Nile crocodiles. Recent observations shows that African rock pythons can hunt adult spotted hyenas.[132]

Communication

[edit]Body language

[edit]

Spotted hyenas have a complex set of postures in communication. When afraid, the ears are folded flat, and are often combined with baring of the teeth and a flattening of the mane. When attacked by other hyenas or by wild dogs, the hyena lowers its hindquarters. Before and during an assertive attack, the head is held high with the ears cocked, mouth closed, mane erect and the hindquarters high. The tail usually hangs down when neutral, though it will change position according to the situation. When a high tendency to flee an attacker is apparent, the tail is curled below the belly. During an attack, or when excited, the tail is carried forward on the back. An erect tail does not always accompany a hostile encounter, as it has also been observed to occur when a harmless social interaction occurs. Although they do not wag their tails, spotted hyenas will flick their tails when approaching dominant animals or when there is a slight tendency to flee. When approaching a dominant animal, subordinate spotted hyenas will walk on the knees of their forelegs in submission.[133] Greeting ceremonies among clan-members consist of two individuals standing parallel to each other and facing opposite directions. Both individuals raise their hind legs and lick each other's anogenital area.[67] During these greeting ceremonies, the penis or pseudo-penis often becomes erect, in both males and females. Erection is usually a sign of submission, rather than dominance, and is more common in males than in females.[134]

Vocalisations

[edit]It is said that feasting Hyaenas engage in violent fights, and there is such a croaking, shrieking and laughing at such times that a superstitious person might really think all the inhabitants of the infernal regions had been let loose.

— Alfred Brehm (1895)[135]

The spotted hyena has an extensive vocal range, with sounds ranging from whoops, fast whoops, grunts, groans, lows, giggles, yells, growls, soft grunt-laughs, loud grunt-laughs, whines and soft squeals. The loud who-oop call, along with the maniacal laughter, are among the most recognisable sounds of Africa. Typically, high-pitched calls indicate fear or submission, while loud, lower-pitched calls express aggression.[136] The pitch of the laugh indicates the hyena's age, while variations in the frequency of notes used when hyenas make noises convey information about the animal's social rank.[137]

Dr. Hans Kruuk compiled the following table on spotted hyena calls in 1972:[138]

| Name | Vocalization | Sound description | Posture | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whoop | A series of 6–9 (sometimes 15) calls lasting 2–3 seconds each and spaced 2–10 seconds apart. The general tone is an "oo" tone which begins in a low pitch and ends with a high note. This sound can be heard more than 5 km away. | Usually done standing, with the mouth opened slightly and the head bent down | Used by both sexes when alone or in a group, and appears to be done spontaneously without external cause | |

| Fast whoop | Similar to the whoop, but higher pitched and with shorter intervals | Tail is either horizontal or high with the ears cocked. Often done while running, with the mouth bent down | Used with other hyenas present just before the onset of an attack, often during a dispute over a kill with lions or other hyenas | |

| Grunt | A soft, low-pitched growling sound which lasts several seconds. | The mouth is closed, and the posture aggressive. | Emitted on the approach of another, unwelcome hyena, and may be followed by chasing | |

| Groan | Similar to above, but more "ooo" sounding and higher in pitch | Before and during meeting ceremonies | ||

| Low | "Ooo" sound with a usually low pitch and lasts several seconds | The mouth is slightly open with the head horizontal. | Like the fast whoop, but with less tendency to attack | |

| Giggle | A series of loud, high-pitched "hee-hee-hee" sounds usually lasting less than 5 seconds. | Running in a fleeing posture with the mouth slightly open | When attacked or chased, usually over a kill | |

| Yell | A loud, high pitched call lasting several seconds | As with the giggle | As with the giggle, but when actually being bitten | |

| Growl | A loud, rattling, low pitched sound lasting several seconds, with an "aa" and "oh" quality | Defensive posture | When under attack, preceding a retaliatory bite | |

| Soft grunt-laugh | A rapid succession of low pitched, soft sounding staccato grunts lasting several seconds | The mouth is closed or slightly open with a fleeing posture and the tail horizontal or high and the ears cocked | When fleeing in surprise from a lion, man or when attacking large prey | |

| Loud grunt-laugh | Louder than the soft grunt-laugh, though still not particularly loud, and often lasts more than 5 minutes | The mouth is the same as in the soft grunt-laugh, but with the tail high and ears cocked | In encounters with lions or other hyena clans | |

| Whine | Loud, high pitched, rapid, drawn out "eeee" sounding squeals | The mouth is slightly open with the head and tail hanging low | Mostly used by cubs when following a female before suckling, or when thwarted from getting food | |

| Soft squeal | Same as above, but softer and without the staccato quality | The mouth is slightly open with the ears flattened and the head tilted to one side with the teeth bared | Used by both cubs and adults encountering a clan-mate after a long separation |

Diseases and parasites

[edit]Spotted hyenas may contract brucellosis, rinderpest[citation needed] and anaplasmosis. They are vulnerable to Trypanosoma congolense, which is contracted by consuming already infected herbivores, rather than through direct infection from tsetse flies.[139] It is known that adult spotted hyenas in the Serengeti have antibodies against rabies, canine herpes, canine brucellosis, canine parvovirus, feline calicivirus, leptospirosis, bovine brucellosis, rinderpest and anaplasmosis. During the canine distemper outbreak of 1993–94, molecular studies indicated that the viruses isolated from hyenas and lions were more closely related to each other than to the closest canine distemper virus in dogs. Evidence of canine distemper in spotted hyenas has also been recorded in the Masai Mara. Exposure to rabies does not cause clinical symptoms or affect individual survival or longevity. Analyses of several hyena saliva samples showed that the species is unlikely to be a rabies vector, thus indicating that the species catches the disease from other animals rather than from intraspecifics. The microfilaria of Dipetalonema dracuneuloides have been recorded in spotted hyenas in northern Kenya. The species is known to carry at least three cestode species of the genus Taenia, none of which are harmful to humans. It also carries protozoan parasites of the genus Hepatozoon in the Serengeti, Kenya and South Africa.[140] Spotted hyenas may act as hosts in the life-cycles of various parasites which start life in herbivores; Taenia hyaenae and T. olnogojinae occur in hyenas in their adult phase. Trichinella spiralis are found as cysts in hyena muscles.[139]

Range, habitat and population

[edit]The spotted hyena's distribution once ranged in Europe from the Iberian Peninsula to the Urals, where it remained for at least one million years.[4] Remains have also been found in the Russian Far East, and it has been theorised that the presence of hyenas there may have delayed the colonisation of North America.[141] During the Last Glacial Maximum, the spotted hyena also roamed Southeast Asia.[142] The causes of the species' extinction in Eurasia are still largely unknown.[4] In Western Europe at least, the spotted hyena's extinction coincided with a decline in grasslands 12,500 years ago. Europe experienced a massive loss of lowland habitats favoured by spotted hyenas, and a corresponding increase in mixed woodlands. Spotted hyenas, under these circumstances, would have been outcompeted by wolves and humans which were as much at home in forests as in open lands, and in highlands as in lowlands. Spotted hyena populations began to shrink roughly 20,000 years ago, completely disappearing from Western Europe between 14 and 11,000 years ago, and earlier in some areas.[143]

Historically, the spotted hyena was widespread throughout Sub-Saharan Africa. It is present in all habitats save for the most extreme desert conditions, tropical rainforests and the top of alpine mountains. Its current distribution is patchy in many places, especially in West Africa. Populations are concentrated in protected areas and surrounding land. There is a continuous distribution over large areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Namibia and the Transvaal Lowveld areas of South Africa.[144] During the 1770s and 1780s the species was still widespread in southern and western South Africa, being recorded on the Cape Peninsula and Cape Flats, and near present-day Somerset West, Riviersonderend, Mossel Bay, George, Joubertina, Gamtoos River, Jansenville, Cannon Rocks, Alice, Onseepkans and Augrabies Falls.[145]

The species dwells in semi-deserts, savannah, open woodland, dense dry woodland, and mountainous forests up to 4,000 m in altitude. It is scarce or absent in tropical rainforests and coastal areas. Its preferred habitats in west Africa include the Guinea and Sudan savannahs, and is absent in the belt of dense coastal forest. In the Namib Desert, it occurs in riverine growth along seasonal rivers, the sub-desertic pro-Namib and the adjoining inland plateau. In ideal habitats, the spotted hyena outnumbers other large carnivores, including other hyena species. However, the striped and brown hyena occur at greater densities than the spotted species in desert and semi-desert regions.[146] Population densities based on systematic censuses vary substantially, from 0.006 to 1.7 individuals per km2.[1]

Relationships with humans

[edit]Cultural depictions

[edit]

In Africa, the spotted hyena is usually portrayed as an abnormal and ambivalent animal, considered to be sly, brutish, necrophagous and dangerous. It further embodies physical power, excessiveness, ugliness, stupidity, as well as sacredness. Spotted hyenas vary in their folkloric and mythological depictions, depending on the ethnic group from which the tales originate. It is often difficult to know whether or not spotted hyenas are the specific hyena species featured in such stories, particularly in West Africa, as both spotted and striped hyenas are often given the same names.[147] In west African tales, spotted hyenas symbolise immorality, dirty habits, the reversal of normal activities, and other negative traits, and are sometimes depicted as bad Muslims who challenge the local animism that exists among the Beng in Côte d'Ivoire. In East Africa, Tabwa mythology portrays the spotted hyena as a solar animal that first brought the sun to warm the cold earth.[147]

Spotted hyenas feature prominently in the rituals of certain African cultures. In the Gelede cult of the Yoruba people of Benin and Southwest Nigeria, a spotted hyena mask is used at dawn to signal the end of the èfè ceremony. As the spotted hyena usually finishes the meals of other carnivores, the animal is associated with the conclusion of all things. Among the Korè cult of the Bambara people in Mali, the belief that spotted hyenas are hermaphrodites appears as an ideal in-between in the ritual domain. The role of the spotted hyena mask in their rituals is often to turn the neophyte into a complete moral being by integrating his male principles with femininity. The Beng people believe that upon finding a freshly killed hyena with its anus everted, one must plug it back in, for fear of being struck down with perpetual laughter. They also view spotted hyena faeces as contaminating, and will evacuate a village if a hyena relieves itself within village boundaries.[147] In Harar, Ethiopia, spotted hyenas are regularly fed by the city's inhabitants, who believe the hyenas' presence keeps devils at bay, and associate mystical properties such as fortune telling to them.[148]

As several distinguished authors of the present age have undertaken to reconcile the world to the Great Man-Killer of Modern times; as Aaron Burr has found an apologist, and almost a eulogist; and as learned commentators have recently discovered that even Judas Iscariot was a true disciple, we are rather surprised to find that someone has not undertaken to render the family of Hyenas popular and amiable in the eyes of mankind. Certain it is, that few marked characters in history have suffered more from the malign inventions of prejudice[149]

Traditional Western beliefs about the spotted hyena can be traced back to Aristotle's Historia Animalium, which described the species as a necrophagous, cowardly and potentially dangerous animal. He further described how the hyena uses retching noises to attract dogs. In On the Generation of Animals, Aristotle criticised the erroneous belief that the spotted hyena is a hermaphrodite (which likely originated from the confusion caused by the masculinised genitalia of the female), though his physical descriptions are more consistent with the striped hyena. Pliny the Elder supported Aristotle's depiction, though he further elaborated that the hyena can imitate human voices. Additionally, he wrote how the hyena was held in high regard among the Magi, and that hyena body parts could cure different diseases, give protection and stimulate sexual desire in people.[18]

Natural historians of the 18th and 19th centuries rejected stories of hermaphroditism in hyenas, and recognised the differences between the spotted and striped hyena. However, they continued to focus on the species' scavenging habits, their potential to rob graves and their perceived cowardice. During the 20th century, Western and African stereotypes of the spotted hyena converged; in both Ernest Hemingway's Green Hills of Africa and Disney's The Lion King, the traits of gluttony and comical stupidity, common in African depictions of hyenas, are added to the Western perception of hyenas being cowardly and ugly.[18] After the release of The Lion King, hyena biologists protested against the animal's portrayal: one hyena researcher sued Disney studios for defamation of character,[150] and another – who had organized the animators' visit to the University of California's Field Station for Behavioural Research, where they would observe and sketch captive hyenas[18] – suggested boycotting the film.[151]

Livestock predation

[edit]When targeting livestock, the spotted hyena primarily preys upon cattle, sheep and goats,[11] though hyenas in the southern parts of Tigray Region of Ethiopia preferentially target donkeys.[152] Reports of livestock damage are often not substantiated, and hyenas observed scavenging on a carcass may be mistaken for having killed the animal. The rate at which the species targets livestock may depend on a number of factors, including stock keeping practices, the availability of wild prey and human-associated sources of organic material, such as rubbish. Surplus killing has been recorded in South Africa's eastern Cape Province. Attacks on stock tend to be fewer in areas where livestock is corralled by thorn fences and where domestic dogs are present. One study in northern Kenya revealed that 90% of all cases of livestock predation by hyenas occurred in areas outside the protection of thorn fences.[11]

Attacks on humans and grave desecration

[edit]Like most mammalian predators, the spotted hyena is typically shy in the presence of humans, and has the highest flight distance (up to 300 metres) among African carnivores. However, this distance is reduced during the night, when hyenas are known to follow people closely.[153] Although spotted hyenas do prey on humans in modern times, such incidents are rare. However, attacks on humans by spotted hyenas are likely to be underreported.[154] Man-eating spotted hyenas tend to be large specimens; a pair of man-eating hyenas, responsible for killing 27 people in Mlanje, Malawi, in 1962, were weighed at 72 and 77 kg (159 and 170 lb) after being shot.[155] Victims of spotted hyenas tend to be women, children and sick or infirm men,[156] and there are numerous cases of biologists in Africa being forced up trees to escape them.[155] Attacks occur most commonly in September, when many people sleep outdoors, and bush fires make the hunting of wild game difficult for hyenas.[154][155]

In 1903, Hector Duff wrote of how spotted hyenas in the Mzimba district of Angoniland would wait at dawn outside people's huts and attack them when they opened their doors.[157] In 1908–09 in Uganda, spotted hyenas regularly killed sufferers of African sleeping sickness as they slept outside in camps.[156] Spotted hyenas are widely feared in Malawi, where they have been known to occasionally attack people at night, particularly during the hot season when people sleep outside. Hyena attacks were widely reported in Malawi's Phalombe plain, to the north of Michesi Mountain. Five deaths were recorded in 1956, five in 1957 and six in 1958. This pattern continued until 1961 when eight people were killed.[157] During the 1960s, Flying Doctors received over two dozen cases of hyena attacks on humans in Kenya.[158] An anecdotal 2004 news report from the World Wide Fund for Nature indicates that 35 people were killed by spotted hyenas during a 12-month period in Mozambique along a 20 km stretch of road near the Tanzanian border.[154]

Although attacks against living humans are rare, the spotted hyena readily feeds on human corpses. In the tradition of the Maasai[158] and the Hadza,[159] corpses are left in the open for spotted hyenas to eat. A corpse rejected by hyenas is seen as having something wrong with it, and liable to cause social disgrace, therefore it is not uncommon for bodies to be covered in fat and blood from a slaughtered ox.[158] In Ethiopia, hyenas were reported to feed extensively on the corpses of victims of the 1960 attempted coup[160] and the Red Terror.[161] Hyenas habituated to scavenging on human corpses may develop bold behaviours towards living people; hyena attacks on people in southern Sudan increased during the Second Sudanese Civil War, when human corpses were readily available to them.[162]

Urban hyenas

[edit]In some parts of Africa, spotted hyenas have begun to frequent metropolitan areas, where groups or "clans" of the animals have become a menace. The Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is estimated to have up to a thousand resident hyenas which survive by scavenging rubbish tips and preying on feral dogs and cats. There have also been attacks on homeless people. In 2013, a baby boy was killed by hyenas after being snatched from his mother as she camped near the Hilton Hotel. Some 40 of the animals were reportedly seen alongside a fence bordering the British Embassy compound. In December 2013, a cull was organised and marksmen killed ten hyenas which had occupied wasteland near the city centre.[163]

Hunting and use in traditional medicine

[edit]

The spotted hyena has been hunted for its body parts for use in traditional medicine,[164] for amusement,[18] and for sport, though this is rare, as the species is generally not considered attractive.[164][152] There is fossil evidence of humans in Middle Pleistocene Europe butchering and presumably consuming spotted hyenas.[165] Such incidences are rare in modern Africa, where most tribes, even those known to eat unusual kinds of meat, generally despise hyena flesh.[153]

Several authors during the Scramble for Africa attested that, despite its physical strength, the spotted hyena poses no danger to hunters when captured or cornered. It was often the case that native skinners refused to even touch hyena carcasses, though this was not usually a problem, as hyena skins were not considered attractive.[156][166]

In Burkina Faso, the hyena's tail is used for medicinal and magical purposes. In Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal, the animals' whole body is harvested for bushmeat and medicine. In Malawi and Tanzania, the genitalia, nose tips and tails are used for traditional medicine. In Mozambique, traditional healers use various spotted hyena body parts, particularly the paws.[164] Oromo hunters typically go through ritual purification after killing hyenas.[167] Kujamaat hunters traditionally treat the spotted hyenas they kill with the same respect due to deceased tribal elders, to avoid retribution from hyena spirits acting on behalf of the dead animal.[147]

During the early years of Dutch colonisation in southern Africa, hyenas (referred to as "wolves" by the colonists) were especially susceptible to trapping, as their predilection for eating carrion, and lack of caution about enclosed spaces, worked against them. A feature of many frontier farms was the wolwehok (hyena trap), which was roughly constructed from stone or wood and baited with meat. The trap featured a trap-door, which was designed to shut once the bait was disturbed.[168] In the Cape Colony, spotted hyenas were often hunted by tracking them to their dens and shooting them as they escaped. Another hunting method was to trap them in their dens and dazzle them with torchlight, before stabbing them in the heart with a long knife.[93]

When chased by hunting dogs, spotted hyenas often attack back, unless the dogs are of exceptionally large, powerful breeds. James Stevenson-Hamilton wrote that wounded spotted hyenas could be dangerous adversaries for hunting dogs, recording an incident in which a hyena managed to kill a dog with a single bite to the neck without breaking the skin.[169] Further difficulties in killing spotted hyenas with dogs include the species' thick skin, which prevents dogs from inflicting serious damage to the animal's muscles.[170]

Spotted hyenas in captivity and as pets

[edit]

From a husbandry point of view, hyenas are easily kept, as they have few disease problems and it is not uncommon for captive hyenas to reach 15–20 years of age. One study of the hyena immune system showed that captive hyenas had lower levels for immune defenses than hyenas from the wild population that was used to establish the captive population.[171] Nevertheless, the spotted hyena was historically scantily represented in zoos, and was typically obtained to fill empty cages until more prestigious species could be obtained. In subsequent years, animals considered to be more charismatic were allocated larger and better quality facilities, while hyenas were often relegated to inferior exhibits.

In modern times, the species faces spatial competition from more popular animals, especially large canids. Also, many captive individuals have not been closely examined to confirm their sexes, thus resulting in non-breeding pairs often turning out to be same-sexed individuals. As a result, many captive hyena populations are facing extinction.[172]

During the 19th century, the species was frequently displayed in travelling circuses as oddities. Alfred Brehm wrote that the spotted hyena is harder to tame than the striped hyena, and that performing specimens in circuses were not up to standard.[173] Sir John Barrow described how spotted hyenas in Sneeuberge were trained to hunt game, writing that they were "as faithful and diligent as any of the common domestic dogs".[174]

In Tanzania, spotted hyena cubs may be taken from a communal den by witchdoctors to increase their social status.[158] An April 2004 BBC article described how a shepherd living in the small town of Qabri Bayah about 50 kilometres from Jigjiga, Ethiopia managed to use a male spotted hyena as a livestock guardian dog, suppressing its urge to leave and find a mate by feeding it special herbs.[175] If not raised with adult members of their kind, captive spotted hyenas will exhibit scent marking behaviours much later in life than wild specimens.[85]

Although easily tamed, spotted hyenas are exceedingly difficult to house train,[176] and can be destructive; a captive, otherwise perfectly tame, specimen in the Tower of London managed to tear an 8-foot (2.4 m) long plank nailed to its recently repaired enclosure floor with no apparent effort.[177] During the research leading to the composition of his monograph The Spotted Hyena: A Study of Predation and Social Behavior, Hans Kruuk kept a tame hyena he named Solomon.[106] Kruuk found Solomon's company so congenial, he would have kept him, but Solomon had an insatiable taste for "cheese in the bar of the tourist lounge and bacon off the Chief Park Warden's breakfast table", and no door could hold him back, so Solomon was obliged to live out his days in the Edinburgh Zoo.[178]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bohm, T.; Höner, O.R. (2015). "Crocuta crocuta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T5674A45194782. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T5674A45194782.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Funk 2010, pp. 55–56

- ^ a b c Varela, Sara (2010). "Were the Late Pleistocene climatic changes responsible for the disappearance of the European spotted hyena populations? Hindcasting a species geographic distribution across time" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (17–18): 2027–2035. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.2027V. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ a b Estes 1998, p. 290

- ^ a b c Rosevear 1974, pp. 355–357

- ^ a b Rosevear 1974, p. 353

- ^ a b c d Macdonald 1992, pp. 134–135

- ^ a b c d Drea CM, Frank LG (2003) The social complexity of spotted hyenas. In: Animal Social Complexity: Intelligence, Culture, and Individualized Societies (eds de Waal FBM, Tyack PL). pp. 121–148, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ^ a b c Glickman SE, Cunha GR, Drea CM, Conley AJ and Place NJ. (2006). Mammalian sexual differentiation: lessons from the spotted hyena. Archived 22 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Trends Endocrinol Metab 17:349–356.

- ^ a b c Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e Holekamp, KE; Sakai, ST; Lundrigan, BL (2007). "Social intelligence in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 362 (1480): 523–538. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1993. PMC 2346515. PMID 17289649.

- ^ a b c Estes 1992, pp. 337–338

- ^ Kingdon 1988, p. 262

- ^ Kingdon 1988, p. 264

- ^ Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 33

- ^ a b Spassov, N.; Stoytchev, T. (2004). "The presence of cave hyaena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea) in the Upper Palaeolithic rock art of Europe" (PDF). Historia Naturalis Bulgarica. 16: 159–166. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Glickman, Stephen (1995). "The Spotted Hyena from Aristotle to the Lion King: Reputation is Everything – In the Company of Animals", Social Research, Volume 62

- ^ Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 92 & 101

- ^ Funk 2010, pp. 52–54

- ^ Funk 2010, p. 134

- ^ Wade, D. W. (2006). "Hyenas and Humans in the Horn of Africa" (PDF). The Geographical Review. 96 (4): 609–632. Bibcode:2006GeoRv..96..609G. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2006.tb00519.x. S2CID 162339018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Funk 2010, pp. 57–58

- ^ Funk 2010, pp. 58–59

- ^ Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 16

- ^ Rohland, N; Pollack, JL; Nagel, D; Beauval, C; Airvaux, J; Paabo, S; Hofreiter, M (2005). "The population history of extant and extinct hyenas". Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 (12): 2435–2443. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi244. PMID 16120805.

- ^ Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 1

- ^ Watts, Heather E.; Tanner, Jamie B.; Lundrigan, Barbara L.; Holekamp, Kay E. (2009). "Post-weaning maternal effects and the evolution of female dominance in the spotted hyena". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1665): 2291–2298. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0268. PMC 2677617. PMID 19324728.

- ^ Kurtén 1968, pp. 69–72

- ^ Gilbert, W. Henry; Asfaw, Berhane (2008), Homo erectus: pleistocene evidence from the Middle Awash, Ethiopia, Volume 1 of Middle Awash series, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-25120-2. p. 99.

- ^ Ficarelli, G.; D. Torre. (1970), "Remarks on the taxonomy of hyaenids". Palaeontographia Italica 66:13–33.

- ^ a b Westbury, Michael V.; Hartmann, Stefanie; Barlow, Axel; Preick, Michaela; Ridush, Bogdan; Nagel, Doris; Rathgeber, Thomas; Ziegler, Reinhard; Baryshnikov, Gennady; Sheng, Guilian; Ludwig, Arne; Wiesel, Ingrid; Dalen, Love; Bibi, Faysal; Werdelin, Lars (13 March 2020). "Hyena paleogenomes reveal a complex evolutionary history of cross-continental gene flow between spotted and cave hyena". Science Advances. 6 (11): eaay0456. Bibcode:2020SciA....6..456W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay0456. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7069707. PMID 32201717.

- ^ Reynolds, S.C. (2010). "Where the Wild Things Were: Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Carnivores in the Cradle of Humankind (Gauteng, South Africa) in Relation to the Accumulation of Mammalian and Hominin Assemblages". Journal of Taphonomy. 8 (2–3): 233–257. S2CID 131601883.

- ^ Sheng, Gui-Lian; Soubrier, Julien; Liu, Jin-Yi; Werdelin, Lars; Llamas, Bastien; Thomson, Vicki A.; Tuke, Jonathan; Wu, Lian-Juan; Hou, Xin-Dong; Chen, Quan-Jia; Lai, Xu-Long; Cooper, Alan (29 October 2014). "Pleistocene C hinese cave hyenas and the recent E urasian history of the spotted hyena, C rocuta crocuta". Molecular Ecology. 23 (3): 522–533. Bibcode:2014MolEc..23..522S. doi:10.1111/mec.12576. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 24320717. Retrieved 8 February 2024 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Kurtén, Björn (1988) On evolution and fossil mammals, Columbia University Press, pp. 238–242, ISBN 0-231-05868-3

- ^ a b Kruuk 1972, p. 209

- ^ a b Kruuk 1972, p. 211

- ^ Kruuk 1972, p. 222

- ^ Schaller 1976, p. 248

- ^ Dockner, M. (2006). Comparison of Crocuta crocuta crocuta and Crocuta crocuta spelaea through computer tomography. (Masters Thesis).

- ^ a b Rosevear 1974, pp. 357–358

- ^ Macdonald 1992, p. 118

- ^ Hunter, Luke & Hinde, Gerald (2005) Cats of Africa, Struik, ISBN 1-77007-063-X

- ^ Savage, R. J. G. (1955) Giant deer from Lough Beg. The Irish Naturalists’ Journal 11d: 1–6.

- ^ Tanner, Jaime B, Dumont, Elizabeth, R., Sakai, Sharleen T., Lundrigan, Barbara L & Holekamp, Kay E. (2008), Of arcs and vaults: the biomechanics of bone-cracking in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, 95, 246–255.

- ^ Christiansen and Stephen Wroe, Bite Forces and Evolutionary Adaptations to Feeding Ecology in Carnivores, Ecology, Vol. 88, No. 2

- ^ Binder, Wendy J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (2000). "Development of Bite Strength and Feeding Behaviour in Juvenile Spotted Hyenas (Crocuta crocuta)". Journal of Zoology. 252 (3): 273–83. doi:10.1017/s0952836900000017. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 2

- ^ a b Kingdon 1988, p. 260

- ^ Meloro, Carlo (2007), Plio-Pleistocene large carnivores from the Italian peninsula: functional morphology and macroecology Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II" Dottorato di Ricerca in Scienze della Terra Geologia del Sedimentario "XX Ciclo"

- ^ "Hyena Project". Hyena Project. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Magazine Article". MSU Alumni. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Schmotzer, B. & Zimmerman, A. (15 April 1922). von Eggeling, H. (ed.). "Über die weiblichen Begattungsorgane der gefleckten Hyäne" [About the female sexual organs of the spotted hyena]. Anatomischer Anzeiger (in German). 55 (12/13). Jena, DEU: Gustav Fischer: 257–264, esp. 260. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

Anatomischer Anzeiger: Centralblatt für die gesamte wissenschaftliche Anatomie [Anatomical Gazette: Central Journal for the whole of Scientific Anatomy].

- ^ a b Kruuk 1972, p. 210

- ^ a b c d e Szykman, M.; Van Horn, R. C.; Engh, A.L.; Boydston, E. E.; Holekamp, K. E. (2007). "Courtship and mating in free-living spotted hyenas" (PDF). Behaviour. 144 (7): 815–846. Bibcode:2007Behav.144..815S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.630.5755. doi:10.1163/156853907781476418. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ Cunha, Gerald R.; et al. (2003). "Urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben): a functional histological study" (PDF). Journal of Morphology. 256 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1002/jmor.10085. PMID 12635111. S2CID 26473002.

- ^ Cunha, Gerald R., et al. "The ontogeny of the urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben)." Biology of reproduction 73.3 (2005): 554–564.

- ^ Drea, C. M., et al. "Androgens and masculinization of genitalia in the spotted hyaena." J. Reprod. Fertil 113 (1998): 117–127.

- ^ a b Estes, Richard (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- ^ Kruuk 1972, p. 7

- ^ Kruuk 1972, pp. 240–241

- ^ Kruuk 1972, pp. 276–278

- ^ a b Vullioud, Colin; Davidian, Eve; Wachter, Bettina; Rousset, François; Courtiol, Alexandre; Höner, Oliver P. (19 November 2018). "Social support drives female dominance in the spotted hyaena". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 71–76. Bibcode:2018NatEE...3...71V. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0718-9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 30455441. S2CID 53875904.

- ^ Davidian, Eve; Höner, Oliver (2021). "A king among queens". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 19 (10): 573. Bibcode:2021FrEE...19..573D. doi:10.1002/fee.2441. ISSN 1540-9309. S2CID 244830346.

- ^ Van Horn, Russell C.; McElhinny, Teresa L.; Holekamp, Kay E. (29 August 2003). "Age Estimation and Dispersal in the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta)". Journal of Mammalogy. 84 (3): 1019–1030. doi:10.1644/BBa-023. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ East, Marion L.; Höner, Oliver P.; Wachter, Bettina; Wilhelm, Kerstin; Burke, Terry; Hofer, Heribert (1 May 2009). "Maternal effects on offspring social status in spotted hyenas". Behavioral Ecology. 20 (3): 478–483. doi:10.1093/beheco/arp020. ISSN 1045-2249.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mills & Hofer 1998, p. 36

- ^ a b Macdonald 1992, p. 138

- ^ a b Ilany, A; Booms, AS; Holekamp, KE (2015). "Topological effects of network structure on long-term social network dynamics in a wild mammal". Ecology Letters. 18 (7): 687–695. Bibcode:2015EcolL..18..687I. doi:10.1111/ele.12447. PMC 4486283. PMID 25975663.

- ^ Lewin, N. (25 February 2015). "Socioecological variables predict telomere length in wild spotted hyenas". Biology Letters. 11 (2): 20140991. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0991. PMC 4360110. PMID 25716089.

- ^ Flies, A.S. (30 September 2016). "Socioecological predictors of immune defenses in a wild spotted hyenas". Functional Ecology. 30 (9): 1549–1557. Bibcode:2016FuEco..30.1549F. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12638. PMC 5098940. PMID 27833242.

- ^ Burgener, Nicole; East, Marion L; Hofer, Heribert; Dehnhard, Martin (2008), "Do Spotted Hyena Scent Marks Code for Clan Membership?", Chemical Signals in Vertebrates 11, New York, NY: Springer New York, pp. 169–177, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-73945-8_16, ISBN 978-0-387-73944-1, retrieved 27 November 2023

- ^ Theis, Kevin R.; Venkataraman, Arvind; Dycus, Jacquelyn A.; Koonter, Keith D.; Schmitt-Matzen, Emily N.; Wagner, Aaron P.; Holekamp, Kay E.; Schmidt, Thomas M. (11 November 2013). "Symbiotic bacteria appear to mediate hyena social odors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (49): 19832–19837. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019832T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306477110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3856825. PMID 24218592.

- ^ Kruuk 1972, pp. 251–265

- ^ a b c Kruuk 1972, pp. 27–31

- ^ a b c Kruuk 1972, pp. 230–233

- ^ LiveScience Staff (15 August 2007) "How Hyenas Avoid Incest".

- ^ "It's a dog's life – aggressive male hyenas fail to impress the girls". innovations-report.com. 14 May 2003.

- ^ a b Estes 1998, p. 293