Lascaux: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 3 edits by 202.171.172.90 identified as vandalism to last revision by Purslane. (TW) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The cave was discovered on September 12, 1940 by four teenagers, Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas, as well as Marcel's dog, Robot.<ref name="cave_art"> |

The cave was discovered hello who is borat?(in funny voice)on September 12, 1940 by four teenagers, Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas, as well as Marcel's dog, Robot.<ref name="cave_art"> |

||

{{citation |

{{citation |

||

|title=Cave Art |

|title=Cave Art |

||

Revision as of 04:09, 20 April 2010

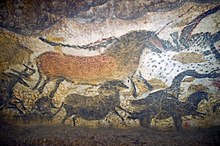

Lascaux is the setting of a complex of caves in southwestern France famous for its Paleolithic cave paintings. The original caves are located near the village of Montignac, in the Dordogne département. They contain some of the best-known Upper Paleolithic art. These paintings are estimated to be 17,000 years old. They primarily consist of realistic images of large animals, most of which are known from fossil evidence to have lived in the area at the time. In 1979, Lascaux was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list along with other prehistoric sites in the Vézère valley.[1]

History

The cave was discovered hello who is borat?(in funny voice)on September 12, 1940 by four teenagers, Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas, as well as Marcel's dog, Robot.[2] The cave complex was opened to the public in 1948.[3] By 1955, the carbon dioxide produced by 1,200 visitors per day had visibly damaged the paintings. The cave was closed to the public in 1963 in order to preserve the art. After the cave was closed, the paintings were restored to their original state, and were monitored on a daily basis. Rooms in the cave include The Great Hall of the Bulls, the Lateral Passage, the Shaft of the Dead Man, the Chamber of Engravings, the Painted Gallery, and the Chamber of Felines.

Lascaux II, a replica of two of the cave halls — the Great Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery — was opened in 1983, 200 meters from the original.[2] Reproductions of other Lascaux artwork can be seen at the Centre of Prehistoric Art at Le Thot, France.

Since 1998 the cave has been beset with a fungus, variously blamed on a new air conditioning system that was installed in the caves, the use of high-powered lights, and the presence of too many visitors.[4] As of 2008, the cave contained black mold which scientists were and still are trying to keep away from the paintings. In January 2008, authorities closed the cave for three months even to scientists and preservationists. A single individual was allowed to enter the cave for 20 minutes once a week to monitor climatic conditions. Now only a few scientific experts are allowed to work inside the cave and just for a few days a month but the efforts to remove the mold have taken a toll, leaving dark patches and damaging the pigments on the walls.[5]

The images

The cave contains nearly 2,000 figures, which can be grouped into three main categories — animals, human figures and abstract signs. Notably, the paintings contain no images of the surrounding landscape or the vegetation of the time[6]. Most of the major images have been painted onto the walls using mineral pigments, although some designs have also been incised into the stone. Many images are too faint to discern, while others have deteriorated.

Over 900 can be identified as animals, and 605 of these have been precisely identified. There are also many geometric figures. Of the animals, equines predominate, with 364 images. There are 90 paintings of stags. Also represented are cattle and bison, each representing 4-5% of the images. A smattering of other images include seven felines, a bird, a bear, a rhinoceros, and a human. Among the most famous images are four huge, black bulls or aurochs in the Hall of the Bulls. There are no images of reindeer, even though that was the principal source of food for the artists.[7]

The most famous section of the cave is The Great Hall of the Bulls where bulls, equines and stags are depicted. But it is the four black bulls that are the dominant figures among the 36 animals represented here. One of the bulls is 17 feet (5.2 m) long — the largest animal discovered so far in cave art. Additionally, the bulls appear to be in motion.[8]

A painting referred to as "The Crossed Bison" and found in the chamber called the Nave is often held as an example of the skill of the Paleolithic cave painters. The crossed hind legs show the ability to use perspective in a manner that wasn't seen again until the 15th century.

In recent years new research has suggested that the Lascaux paintings may incorporate prehistoric star charts. Dr Michael Rappenglueck of the University of Munich argues that some of the non-figurative dot clusters and dots within some of the figurative images correlate with the constellations of Taurus, The Pleiades and the grouping known as the "Summer Triangle"[9]. Based on her own study of the astronomical significance of Bronze Age petroglyphs in the Vallée des Merveilles[10] and her extensive survey of other prehistoric cave painting sites in the region — most of which appear to have been specifically selected because the interiors are illuminated by the setting sun on the day of the winter solstice — French researcher Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewiez has further proposed that the gallery of figurative images in the Great Hall represents an extensive star map and that key points on major figures in the group correspond to stars in the main constellations as they appeared in the Paleolithic[11][12].

An alternative hypothesis proposed by David Lewis-Williams following work with similar art of the San people of Southern Africa is that this type of art is spiritual in nature relating to visions experienced during ritualistic trance-dancing. These trance visions are a function of the human brain and so are independent of geographical location. Nigel Spivey, a professor of classic art and archeology at the University of Cambridge, has further postulated in his series, How Art Made the World, that dot and lattice patterns overlapping the representational images of animals are very similar to hallucinations provoked by sensory-deprivation. He further postulates that the connections between culturally important animals and these hallucinations led to the invention of image-making, or the art of drawing. Further extrapolations include the later transference of image-making behavior from the cave to megalithic sites, and the subsequent invention of agriculture to feed the site builders.

Applying to the Lascaux paintings the iconographic method of analysis (studying position, direction and size of the figures; organization of the composition; painting technique; distribution of the color planes; research of the image center), Thérèse Guiot-Houdart endeavoured to comprehend the symbolic function of the animals, to identify the theme of each image and finally to reconstitute the canvas of the myth illustrated on the rockwalls[13].

See also

- Pre-historic art

- List of archaeological sites sorted by country

- European archaeology

- List of caves

- Cave painting

References

- ^ Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley, UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ^ a b Bahn, Paul G. (2007), Cave Art, Frances Lincoln, pp. 81–85, ISBN 0711226555

- ^

Littlewood, Ian (2002, 2005), A Timeline History of FRANCE, Barnes & Noble, p. 296, ISBN 0-7607-7975-9

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Lichfield, John (12 July 2008), "Six months to save Lascaux", The Independent

- ^ Moore, Molly (1 July 2008), "Debate Over Moldy Cave Art Is a Tale of Human Missteps", Washington Post (requires free registration)

- ^ The Cave of Lascaux official website — Themes

- ^ Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists, Knopf, New York, NY, USA, 2006. 1-4000-4348-4, pp. 96-97

- ^ Gregory Curtis, The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists, Knopf, New York, NY, USA, 2006. 1-4000-4348-4, p. 102

- ^ Whitehouse, David (9 August 2000), Ice Age star map discovered, BBC News

- ^ Archeociel: Vallée des Merveilles

- ^ Archeociel : Chantal Jègues Wolkiewiez

- ^ "The Lascaux Cave: A Prehistoric Sky-Map

- ^ [T. Guiot-Houdart, Lascaux et les mythes, Périgueux 2004, ed. Pilote 24 (356 p., 8 col.ill., numerous schemata)]

Further reading

- Curtis, Gregory (2006). The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. New York, New York, USA: Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4348-4.

- Lewis-Williams, David (2004). The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28465-2.

- Bataille, Georges (2005). The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture. New York, New York: Zone Books. ISBN 1-890951-55-2.

- Joseph Nechvatal, "Immersive Excess in the Apse of Lascaux", Technonoetic Arts 3, no3. 2005

- Brigitte and Gilles Delluc, Discovering Lascaux, Sud Ouest edit., Bordeaux, 2006

External links

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Lascaux Cave Official Lascaux Web site, from the French Ministry of Culture.

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Lascaux Cave some info on the cave and more links

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Lascaux Cave — Saving Beauty notes on damage inflicted on the cave, adapted from Time Magazine 2006/5/29

- Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Save Lascaux Official website of the International Committee for the Preservation of Lascaux.