Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

| Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Landouzy–Dejerine muscular dystrophy, FSHMD, FSH |

| |

| A diagram showing the muscles commonly affected by FSHD | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Neurology, neuromuscular medicine |

| Symptoms | Facial weakness, scapular winging, foot drop |

| Complications | Chronic pain, dry eyes, and shoulder instability; less commonly retinal disease, scoliosis, and respiratory insufficiency |

| Usual onset | Ages 15 – 30 years |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Typically classified by genetic cause (FSHD1, FSHD2). Sometimes classified by disease manifestation (eg, infantile-onset) |

| Causes | Genetic (inherited or new mutation) |

| Risk factors | Male sex, extent of genetic mutation |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing |

| Differential diagnosis | Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (especially calpainopathy), Pompe disease, mitochondrial myopathy, polymyositis[2] |

| Management | Physical therapy, bracing, reconstructive surgery |

| Medication | Clinical trials ongoing |

| Prognosis | Progressive, unaffected life expectancy |

| Frequency | Up to 1/8,333[2] |

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a type of muscular dystrophy, a group of heritable diseases that cause degeneration of muscle and progressive weakness. Per the name, FSHD tends to sequentially weaken the muscles of the face, those that position the scapula, and those overlying the humerus bone of the upper arm.[2][3] These areas can be spared, and muscles of other areas usually are affected, especially those of the chest, abdomen, spine, and shin. Almost any skeletal muscle can be affected in advanced disease. Abnormally positioned, termed 'winged', scapulas are common, as is the inability to lift the foot, known as foot drop. The two sides of the body are often affected unequally. Weakness typically manifests at ages 15–30 years.[4] FSHD can also cause hearing loss and blood vessel abnormalities at the back of the eye.

FSHD is caused by a genetic mutation leading to deregulation of the DUX4 gene.[5] Normally, DUX4 is expressed (i.e., turned on) only in select human tissues, most notably in the very young embryo. In the remaining tissues, it is repressed (i.e., turned off).[6][7] In FSHD, this repression fails in muscle tissue, allowing sporadic expression of DUX4 throughout life. Deletion of DNA in the region surrounding DUX4 is the causative mutation in 95% of cases, termed "D4Z4 contraction" and defining FSHD type 1 (FSHD1).[8] FSHD caused by other mutations is FSHD type 2 (FSHD2). For disease to develop, also required is a 4qA allele, which is a common variation in the DNA next to DUX4. The chances of a D4Z4 contraction with a 4qA allele being passed on to a child is 50% (autosomal dominant);[2] in 30% of cases, the mutation arose spontaneously.[4] Mutations of FSHD cause inadequate DUX4 repression by unpacking the DNA around DUX4, making it accessible to be copied into messenger RNA (mRNA). The 4qA allele stabilizes this DUX4 mRNA, allowing it to be used for production of DUX4 protein.[9] DUX4 protein is a modulator of hundreds of other genes, many of which are involved in muscle function.[2][5] How this genetic modulation causes muscle damage remains unclear.[2]

Signs, symptoms, and diagnostic tests can suggest FSHD; genetic testing usually provides definitive diagnosis.[2] FSHD can be presumptively diagnosed in an individual with signs/symptoms and an established family history. No intervention has proven effective for slowing progression of weakness.[10] Screening allows for early detection and intervention for various disease complications. Symptoms can be addressed with physical therapy, bracing, and reconstructive surgery such as surgical fixation of the scapula to the thorax.[11] FSHD affects up to 1 in 8,333 people,[2] putting it in the three most common muscular dystrophies with myotonic dystrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[12][13] Prognosis is variable. Many are not significantly limited in daily activity, whereas a wheel chair or scooter is required in 20% of cases.[14] Life expectancy is not affected, although death can rarely be attributed to respiratory insufficiency due to FSHD.[15]

FSHD was first distinguished as a disease in the 1870s and 1880s when French physicians Louis Théophile Joseph Landouzy and Joseph Jules Dejerine followed a family affected by it, thus the initial name Landouzy–Dejerine muscular dystrophy. Their work is predated by descriptions of probable individual FSHD cases.[16][17][18] The significance of D4Z4 contraction on chromosome 4 was established in the 1990s. The DUX4 gene was discovered in 1999, found to be expressed and toxic in 2007, and in 2010 the genetic mechanism causing its expression was elucidated. In 2012, the gene most frequently mutated in FSHD2 was identified. In 2019, the first drug designed to counteract DUX4 expression entered clinical trials.[19]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Classically, weakness develops in the face, then the shoulder girdle, then the upper arm.[10] These muscles can be spared and other muscles usually are affected. The order of muscle involvement can cause the appearance of weakness "descending" from the face to the legs.[10] Distribution and degree of muscle weakness is extremely variable, even between identical twins.[20][21] Musculoskeletal pain is very common, most often described in the neck, shoulders, lower back, and the back of the knee.[22][4] Fatigue is also common.[4] Muscle weakness usually becomes noticeable on one side of the body before the other, a hallmark of the disease.[14] The right shoulder and arm muscles are more often affected than the left upper extremity muscles, independent of handedness.[23]: 139 [24][25][26] Otherwise, neither side of the body has been found to be at more risk. Classically, symptoms appear in those 15–30 years of age, although adult onset can also occur.[4] Infantile-onset (also called early-onset), defined as onset of before age 10, occurs in 10% of affected individuals.[10] FSHD1 with a very large D4Z4 deletion (EcoRI 10-11 kb) is more strongly associated with infantile onset and severe weakness.[27] Absence or near absence of symptoms is not uncommon, approaching up to 30% of mutation-carrying individuals in select FSHD1 families.[10] On average, FSHD2 presents 10 years later than FSHD1.[28] Otherwise, FSHD1 and FSHD2 are indistinguishable on the basis of weakness.[27] Disease progression is slow, and long static phases, in which no progression is apparent, is not uncommon.[29] Less commonly, individual muscles rapidly deteriorate over several months.[2] The symptom burden of FSHD is typically more severe than it is perceived to be by those without the disease.[30][31][32][33]

Face

[edit]Weakness of the muscles of the face is the most distinguishing sign of FSHD.[4] It is typically the earliest sign, although it is rarely the initial complaint.[4] At least mild facial weakness can be found in 90% or more with FSHD.[29][24] One of the most common deficits is inability to close the eyelids, which can result in sleeping with the eyelids open and dry eyes.[4] The implicated muscle is the orbicularis oculi muscle.[4] Another common deficit is inability to purse the lips, causing inability to pucker, whistle, or blow up a balloon.[4] The implicated muscle is the orbicularis oris muscle.[4] A third common deficit is inability raise the corners of the mouth, causing a "horizontal smile," which looks more like a grin.[4] Responsible is the zygomaticus major muscle.[4]

Weakness of facial muscles contributes to difficulty pronouncing words.[34] Facial expressions can appear diminished, arrogant, grumpy, or fatigued.[4] Muscles used for chewing and moving the eyes are not affected.[24][14] Difficulty swallowing is not typical, although can occur in advanced cases, which is at least in part due to facial muscle weakness.[35][34] FSHD is generally progressive, but it is not established whether facial weakness is progressive or stable throughout life.[36]

Shoulder, chest, and arm

[edit]

After the facial weakness, weakness usually develops in the muscles of the chest and those that span from scapula to thorax. Symptoms involving the shoulder, such as difficulty working with the arms overhead, are the initial complaint in 80% of cases.[24][14] Predominantly, the serratus anterior and middle and lower trapezii muscles are affected;[4] the upper trapezius is often spared.[14] Trapezius weakness causes the scapulas to become downwardly rotated and protracted, resulting in winged scapulas, horizontal clavicles, and sloping shoulders; arm abduction is impaired. Serratus anterior weaknesss impairs arm flexion, and worsening of winging can be demonstrated when pushing against a wall. Muscles spanning from the scapula to the arm are generally spared, which include deltoid and the rotator cuff muscles.[37][38] The deltoid can be affected later on, especially the upper portion.[4]

Severe muscle wasting can make bones and spared shoulder muscles very visible, a characteristic example being the "poly-hill" sign elicited by arm elevation.[4] The first "hill" or bump is the upper corner of scapula appearing to "herniate" up and over the rib cage. The second hill is the AC joint, seen between a wasted upper trapezius and wasted upper deltoid. The third hill is the lower deltoid, distinguishable between the wasted upper deltoid and wasted humeral muscles.[4] Shoulder weakness and pain can in turn lead to shoulder instability, such as recurrent dislocation, subluxation, or downward translation of the humeral head.[39]

Also affected is the chest, particularly the parts of the pectoralis major muscle that connect to the sternum and ribs. The part that connects to the clavicle is less often affected. This muscle wasting pattern can contribute to a prominent horizontal anterior axillary fold.[40][4] Beyond this point the disease does not progress further in 30% of familial cases.[24][14] After upper torso weakness, weakness can "descend" to the upper arms (biceps muscle and, particularly, the triceps muscle).[24] The forearms are usually spared, resulting in an appearance some compare to the fictional character Popeye,[4] although when the forearms are affected in advanced disease, the wrist extensors are more often affected.[24]

Lower body and trunk

[edit]After the upper body, weakness can next appear in either the pelvis, or it "skips" the pelvis and involves the tibialis anterior (shin muscle), causing foot drop. One author considers the pelvic and thigh muscles to be the last group affected.[24] Pelvic weakness can manifest as a Trendelenburg's sign.[4] Weakness of the back of the thigh (hamstrings) is more common than weakness of the front of the thigh (quadriceps).[4] In more severe cases, especially infantile FSHD, there can be anterior pelvic tilt, with associated hyperextension of the knees.[41]

Weakness can also occur in the abdominal muscles and paraspinal muscles, which can manifest as a protuberant abdomen and lumbar hyperlordosis.[2][4] Abdominal weakness can cause inability to do a sit-up or the inability to turn from one side to the other while lying on one's back.[4] Of the rectus abdominis muscle, the lower portion is preferentially affected, manifesting as a positive Beevor's sign.[4][2] In advanced cases, neck extensor weakness can cause the head to lean towards the chest, termed head drop.[24]

Non-muscular

[edit]

The most common non-musculoskeletal manifestation of FSHD is abnormalities in the small arteries (arterioles) in the retina. Tortuosity of the arterioles is seen in approximately 50% of those with FSHD. Less common arteriole abnormalities include telangiectasias and microaneurysms.[42][43] These abnormalities of arterioles usually do not affect vision or health, although a severe form of it mimics Coat's disease, a condition found in about 1% of FSHD cases and more frequently associated with large 4q35 deletions.[2][44] High-frequency sensorineural hearing loss can occur in those with large 4q35 deletions, but otherwise is no more common compared to the general population.[2] Large 4q35 deletion can lead to various other rare manifestations.[45]

Scoliosis can occur, thought to result from weakness of abdominal, hip extensor, and spinal muscles.[46][47] Conversely, scoliosis can be viewed as a compensatory mechanism to weakness.[46] Breathing can be affected, associated with kyphoscoliosis and wheelchair use; it is seen in one-third of wheelchair-using patients.[2] However, ventilator support (nocturnal or diurnal) is needed in only 1% of cases.[2][48] Although there are reports of increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias, general consensus is that the heart is not affected.[14]

Genetics

[edit]

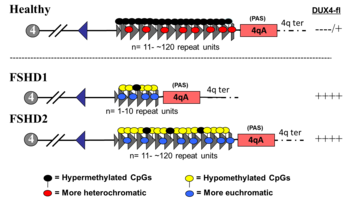

The genetics of FSHD is complex.[2] FSHD and the myotonic dystrophies have unique genetic mechanisms that differ substantially from the rest of genetic myopathies.[49] The DUX4 gene is the focal point of FSHD genetics. Normally, full-length DUX4 protein (DUX4-fl) is expressed during early embryogenesis, in testicular tissue of adults, and in the thymus; in all other tissues it is repressed.[50] In FSHD, within muscle tissue there is failure of DUX4 repression and continued production of DUX4-fl protein, which is toxic to muscles.[2][8][50] The mechanism of failed DUX4 repression is hypomethylation of DUX4 and its surrounding DNA on the tip of chromosome 4 (4q35), allowing transcription of DUX4 into messenger RNA (mRNA). Several mutations can result in disease, upon which FSHD is sub-classified into FSHD type 1 (FSHD1) and FSHD type 2 (FSHD2).[27] Disease can only result when a mutation is present in combination with select, commonly found variations of 4q35, termed haplotype polymorphisms, which are roughly dividable into the groups 4qA and 4qB.[51] A 4qA haplotype polymorphism, often referred to as a 4qA allele, is necessary for disease, as it contains a polyadenylation sequence that allows DUX4 mRNA to resist degradation long enough to be translated into DUX4 protein.[8]

DUX4 and the D4Z4 repeat array

[edit]

| CEN | centromeric end | TEL | telomeric end |

| NDE box | non-deleted element | PAS | polyadenylation site |

| triangle | D4Z4 repeat | trapezoid | partial D4Z4 repeat |

| white box | pLAM | gray boxes | DUX4 exons 1, 2, 3 |

| arrows | |||

| corner | promoters | straight | RNA transcripts |

| black | sense | red | antisense |

| blue | DBE-T | dashes | dicing sites |

DUX4 resides within the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array, which is a DNA sequence composed of a variable number of tandemly repeated large DNA segments (ie, repeats). The D4Z4 repeat array is located at the tip of the large arm of chromosome 4, abbreviated as '4q35'.[52] Each D4Z4 repeat is 3.3 kilobase pairs (kb) long and is the site of epigenetic regulation, containing both heterochromatin and euchromatin structures.[53][54] In FSHD, the heterochromatin structure is lost, becoming euchromatin,[53] which consists of less methylation of DNA, and altered methylation of histones.[55] Histone methylation patterns differ slightly between FSHD1 and FSHD2.[55]

The subtelomeric region of chromosome 10q contains a tandem repeat structure highly homologous (99% identical) to 4q35,[8][51] containing "D4Z4-like" repeats with protein-coding regions identical to DUX4 (D10Z10 repeats and DUX4L10, respectively).[8][56] Because 10q usually lacks a polyadenylation sequence, it is usually not implicated in disease. However, chromosomal rearrangements can occur between 4q and 10q repeat arrays, and involvement in disease is possible if a 4q D4Z4 repeat and polyadenylation signal are transferred onto 10q,[57][8][58] or if rearrangement causes FSHD1.

D4Z4 repeat array types are subclassified into 4qA and 4qB alleles, with only 4qA alleles causing disease. 4qA alleles are defined by a specific sequence of DNA immediately downstream to the D4Z4 repeat array: a 260 base pair region named pLAM, followed by a 6,200 base pair beta satellite region.[9][59] 4qA and 4qB alleles, together, are able to be subdivided into at least 17 types,[51] based on the DNA upstream from the D4Z4 repeat array, the presence/absence of restriction enzyme sites within D4Z4, the size of the last D4Z4 repeat element, and the DNA present downstream to the D4Z4 repeat array.[59] For example, the most common 4qA allele, 4A161, has 161 nucleotides in the region upstream from the D4Z4 repeat array,[27] and can in turn be subdivided into 4A161S and 4A161L (short and long), which are characterized by a flanking D4Z4 repeat units of 300 nucleotides and 1,900 nucleotides, respectively.[59]

DUX4 consists of three exons. Exons 1 and 2 are in each repeat; only exon 1 encodes for DUX4 protein. Exon 3 is in the pLAM region telomeric to the last partial repeat,[8][7] and it can vary in length depending on the type of 4qA allele.[60] A polyadenylation signal is within exon 3. Because exon 3 and its containing polyadenylation signal are not contained within each D4Z4 repeat, only the last D4Z4 repeat of a D4Z4 repeat array can encode a stable mRNA transcript for the production of DUX4 protein.[50] These transcripts can be spliced several different ways to form mature RNA. One of these transcripts encode only a portion of DUX4 protein, termed DUX4-s (DUX4-short).[50] DUX4-s is found in low amounts in a variety of healthy tissues, including healthy muscle; its function is not entirely clear.[50] The remaining transcript versions encode the full length of DUX4 protein (DUX4-fl), differing only in the noncoding regions.[50] Only certain versions of these DUX4-fl encoding mature RNAs are implicated in FSHD.[50] Beyond just the DUX4 region, multiple RNA transcripts are produced from the D4Z4 repeat array, both sense and antisense, some of which might be degraded in areas to produce si-like small RNAs.[27] Some transcripts that originate centromeric to the D4Z4 repeat array at the non-deleted element (NDE), termed D4Z4 regulatory element transcripts (DBE-T), could play a role in DUX4 derepression.[27][61] One proposed mechanism is that DBE-T leads to the recruitment of the trithorax-group protein Ash1L, an increase in H3K36me2-methylation, and ultimately de-repression of 4q35 genes.[62]

DNA methylation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSHD1 | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| FSHD2* | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| *Chromatin profiles not fully characterized for DNMT3B mutation[55] | ||||

FSHD1

[edit]FSHD involving deletion of D4Z4 repeats (termed 'D4Z4 contraction') on 4q is classified as FSHD1, which accounts for 95% of FSHD cases.[2] Typically, chromosome 4 includes between 11 and 150 D4Z4 repeats.[53][8] In FSHD1, there are 1–10 D4Z4 repeats.[8] The number of repeats is roughly inversely related to disease severity. Namely, those with 8–10 repeats tend to have the mildest presentations, sometimes with no symptoms; those with 4–7 repeats have moderate disease that is highly variable; and those with 1–3 repeats are more likely to have severe, atypical, and early-onset disease.[63] Deletion of the entire D4Z4 repeat array does not result in FSHD because then there are no complete copies of DUX4 to be expressed, although other birth defects result.[64][8] One contracted D4Z4 repeat array with an adjoining 4qA allele is sufficient to cause disease, so inheritance is autosomal dominant. De novo (new) mutations are implicated in 10–30% of cases,[4] up to 40% of which exhibit somatic mosaicism.[14] In an individual with mosaic FSHD, the severity of disease is correlated to the proportion of their cells carrying the mutation.[14]

It has been proposed that FSHD1 undergoes anticipation, a phenomenon primarily associated with trinucleotide repeat disorders in which disease manifestation worsens with each subsequent generation.[65] As of 2019, more detailed studies are needed to definitively show whether or not anticipation occurs.[66] If anticipation does occur in FSHD, the mechanism is different than that of trinucleotide repeat disorders, since D4Z4 repeats are much larger than trinucleotide repeats, an underabundance of repeats (rather than overabundance) causes disease, and the repeat array size in FSHD is stable across generations.[67]

FSHD2

[edit]FSHD with a D4Z4 array repeat size of 11 or greater is classified as FSHD2, which constitutes 5% of FSHD cases.[2] A 4qA allele is still required, and its adjacent D4Z4 repeat array is typically borderline shortened, with less than 30 repeats. A deactivating mutation of one of several DNA methylation genes is required for FSHD2, which contributes to hypomethylation of a borderline shortened D4Z4 repeat array, at which the genetic mechanism converges with FSHD1.[68][10] At least 85% of FSHD2 cases involve mutations in the gene SMCHD1 (structural maintenance of chromosomes flexible hinge domain containing 1) on chromosome 18.[10] Specific mutations of SMCHD1 are also associated with Bosma arhinia and microphtalmia syndrome.[55] Another cause of FSHD2 is mutation in DNMT3B (DNA methyltransferase 3B).[69][70] Mutations in DNMT3B can also cause ICF syndrome.[55] As of 2020, early evidence indicates that a third cause of FSHD2 is mutation of the LRIF1 gene, which encodes the protein ligand-dependent nuclear receptor-interacting factor 1 (LRIF1).[71] LRIF1 is known to interact with the SMCHD1 protein.[71] As of 2019, it is presumed that mutation of additional, unidentified genes can cause FSHD2.[2]

For FSHD2 associated with SMCHD1 or DNMT3B mutation, only one allele needs to be abnormal. These FSHD2-causative genes are not located next to the required D4Z4 array/4qA allele within the genome, and are thus inherited independently, resulting in a biallelic digenic inheritance pattern. For example, one parent without FSHD can pass on an SMCHD1 mutation, and the other parent, also without FSHD, can pass on a borderline-shortened D4Z4/4qA allele, bearing a child with FSHD2.[68][70] For FSHD2 associated with LRIF1 mutation, both LRIF1 alleles need to be mutated, which theoretically yields an even more complex inheritance pattern, termed trialleic digenic.[71][72]

Two ends of a disease spectrum

[edit]FSHD1 and FSHD2 have been traditionally viewed as separate entities with distinct genetic causes (albeit, the downstream genetic mechanisms merge).[73] Alternatively, the genetic causes of FSHD1 and FSHD2 can be viewed as risk factors, each contributing to an FSHD disease spectrum.[73] Not rarely, an affected individual seems to have contributions from both.[63] For example, in those with FSHD2, although they have do not have a 4qA allele with D4Z4 repeat number less than 11, they still have one less than 30 (shorter than the upper limit seen in the general population), suggesting that a large number of D4Z4 repeats can prevent the effects of an SMCHD1 mutation.[63][10] Further studies may be needed to determine the upper limit of D4Z4 repeats in FSHD2.[63]

In those with FSHD1 and FSHD2, that is, having 10 or fewer repeats with an adjacent 4qA allele and an SMCHD1 mutation, the disease manifests more severely, illustrating that the effects of each mutation are additive.[74] A combined FSHD1/FSHD2 presentation is most common in those with 9–10 repeats. A possible explanation is that a sizable portion of the general population has 9–10 repeats with difficult to detect or no disease, yet with the additive effect of an SMCHD1 mutation, symptoms are severe enough for a diagnosis to be made.[63] The 9–10 repeat size can be considered as an overlap zone between FSHD1 and FSDH2.[63]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Molecular

[edit]

As of 2020, there seems to be a consensus that aberrant expression of DUX4 in muscle is the cause of FSHD.[75] DUX4 is expressed in extremely small amounts, detectable in 1 out of every 1000 immature muscle cells (myoblast), which appears to increase after myoblast maturation, in part because the cells fuse as they mature, and a single nucleus expressing DUX4 can provide DUX4 protein to neighboring nuclei from fused cells.[76]

It remains an area of active research how DUX4 protein causes muscle damage.[77] DUX4 protein is a transcription factor that regulates many other genes. Some of these genes are involved in apoptosis, such as p53, p21, MYC, and β-catenin, and indeed it seems that DUX4 protein makes muscle cells more prone to apoptosis. Other DUX4 protein-regulated genes are involved in oxidative stress, and indeed it seems that DUX4 expression lowers muscle cell tolerance of oxidative stress. Variation in the ability of individual muscles to handle oxidative stress could partially explain the muscle involvement patterns of FSHD. DUX4 protein downregulates many genes involved in muscle development, including MyoD, myogenin, desmin, and PAX7, and indeed DUX4 expression has shown to reduce muscle cell proliferation, differentiation, and fusion. DUX4 protein regulates a few genes that are involved in RNA quality control, and indeed DUX4 expression has been shown to cause accumulation of RNA with subsequent apoptosis.[75] Estrogen seems to play a role in modifying DUX4 protein effects on muscle differentiation, which could explain why females are lesser affected than males, although it remains unproven.[78]

The cellular hypoxia response has been reported in a single study to be the main driver of DUX4 protein-induced muscle cell death. The hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are upregulated by DUX4 protein, possibly causing pathologic signaling leading to cell death.[79]

Another study found that DUX4 expression in muscle cells led to the recruitment and alteration of fibrous/fat progenitor cells, which helps explain why muscles become replaced by fat and fibrous tissue.[76]

A single study implicated RIPK3 in DUX4-mediated cell death.[80]

Muscle histology

[edit]

Unlike other muscular dystrophies, early muscle biopsies show only mild degrees of fibrosis, muscle fiber hypertrophy, and displacement of nuclei from myofiber peripheries (central nucleation).[27] More often found is inflammation.[27] There can be endomysial inflammation, primarily composed of CD8+ T-cells, although these cells do not seem to directly cause muscle fiber death.[27] Endomysial blood vessels can be surrounded by inflammation, which is relatively unique to FSHD, and this inflammation contains CD4+ T-cells.[27] Inflammation is succeeded by deposition of fat (fatty infiltration), then fibrosis.[81][27] Individual muscle fibers can appear whorled, moth-eaten, and, especially, lobulated.[82]

Muscle involvement pattern

[edit]Why certain muscles are preferentially affected in FSHD remains unknown. There are multiple trends of involvement seen in FSHD, possibly hinting at underlying pathophysiology. Individual muscles can weaken while adjacent muscles remain strong.[83] The right shoulder and arm muscles are more often affected than the left upper extremity muscles, a pattern also seen in Poland syndrome and hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy; this could reflect a genetic, developmental/anatomic, or functional-related mechanism.[24][25] The deltoid is often spared, which is not seen in any other condition that affects the muscles around the scapula.[36]

Medical imaging (CT and MRI) have shown muscle involvement not readily apparent otherwise[37]

- A single MRI study shows the teres major muscle to be commonly affected.[38]

- The semimembranosus muscle, part of the hamstrings, is commonly affected,[25][84][85] deemed by one author to be "the most frequently and severely affected muscle."[2]

- Of the quadriceps muscles, the rectus femoris is preferentially affected[84]

- Of the gastrocnemius, the medial section is preferentially affected;[84][85]

- The iliopsoas, a hip flexor muscle, is very often spared.[85][2]

Retinopathy

[edit]Tortuosity of the retinal arterioles, and less often microaneurysms and telangiectasia, are commonly found in FSHD.[42] Abnormalities of the capillaries and venules are not observed.[42] One theory for why the arterioles are selectively affected is that they contain smooth muscle.[42] The degree of D4Z4 contraction correlates to the severity of tortuosity of arterioles.[42] It has been hypothesized that retinopathy is due to DUX4-protein-induced modulation of the CXCR4–SDF1 axis, which has a role in endothelial tip cell morphology and vascular branching.[42]

Diagnosis

[edit]

FSHD can be presumptively diagnosed in many cases based on signs, symptoms, and/or non-genetic medical tests, especially if a first-degree relative has genetically confirmed FSHD.[10] Genetic testing can provide definitive diagnosis.[4] In the absence of an established family history of FSHD, diagnosis can be difficult due to the variability in how FSHD manifests.[86]

Genetic testing

[edit]Genetic testing is the gold standard for FSHD diagnosis, as it is the most sensitive and specific test available.[2] Commonly, FSHD1 is tested for first.[2] A shortened D4Z4 array length (EcoRI length of 10 kb to 38 kb) with an adjacent 4qA allele supports FSHD1.[2] If FSHD1 is not present, commonly FSHD2 is tested for next by assessing methylation at 4q35.[2] Low methylation (less than 20%) in the context of a 4qA allele is sufficient for diagnosis.[2] The specific mutation, usually one of various SMCHD1 mutations, can be identified with next-generation sequencing (NGS).[87]

Assessing D4Z4 length

[edit]Measuring D4Z4 length is technically challenging due to the D4Z4 repeat array consisting of long, repetitive elements.[88] For example, NGS is not useful for assessing D4Z4 length, because it breaks DNA into fragments before reading them, and it is unclear from which D4Z4 repeat each sequenced fragment came.[4] In 2020, optical mapping became available for measuring D4Z4 array length, which is more precise and less labor-intensive than southern blot.[89] Molecular combing is also available for assessing D4Z4 array length.[90] These methods, which physical measure the size of the D4Z4 repeat array, require specially prepared high quality and high molecular weight genomic DNA (gDNA) from serum, increasing cost and reducing accessibility to testing.[91]

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was the first genetic test developed and is still used as of 2020, although it is being phased out by newer methods. It involves dicing the DNA with restriction enzymes and sorting the resulting restriction fragments by size using southern blot. The restriction enzymes EcoRI and BlnI are commonly used. EcoRI isolates the 4q and 10q repeat arrays, and BlnI dices the 10q sequence into small pieces, allowing 4q to be distinguished.[4][51] The EcoRI restriction fragment is composed of three parts: 1) 5.7 kb proximal part, 2) the central, variable size D4Z4 repeat array, and 3) the distal part, usually 1.25 kb.[92] The proximal portion has a sequence of DNA stainable by the probe p13E-11, which is commonly used to visualize the EcoRI fragment during southern blot.[51] The name "p13E-11" reflects that it is a subclone of a DNA sequence designated as cosmid 13E during the human genome project.[93][94] Considering that each D4Z4 repeat is 3.3 kb, and the EcoRI fragment contains about 5 kb of DNA that is not part of the D4Z4 repeat array, the number of D4Z4 units can be calculated.[78]

- D4Z4 repeats = (EcoRI length - 5) / 3.3

Sometimes 4q or 10q will have a combination of D4Z4 and D4Z4-like repeats due to DNA exchange between 4q and 10q, which can yield erroneous results, requiring more detailed workup.[51] Sometimes D4Z4 repeat array deletions can include the p13E-11 binding site, warranting use of alternate probes.[51][95]

Assessing methylation status

[edit]Methylation status of 4q35 is traditionally assessed after FSHD1 testing is negative. Methylation sensitive restriction enzyme (MSRE) digestion showing hypomethylation has long been considered diagnostic of FSHD2.[91] Other methylation assays have been proposed or used in research settings, including methylated DNA immunoprecipitation and bisulfite sequencing, but are not routinely used in clinical practice.[96][91] Bisulfite sequencing, if validated, would be valuable due to it being able to use lower quality DNA sources, such as those found in saliva.[91]

Auxiliary testing

[edit]

Other tests can support the diagnosis of FSHD, although they are all less sensitive and less specific than genetic testing.[97][4] Nonetheless, they can rule out similar-appearing conditions.[14]

- Creatine kinase (CK) blood level is often ordered when muscle damage is suspected. CK is an enzyme found in muscle, leaking into the blood when muscles become damaged. In FSHD, CK level is normal to mildly elevated,[2] never exceeding five times the upper limit of normal.[4]

- Electromyogram (EMG) measures the electrical activity in the muscle. EMG can show nonspecific signs of muscle damage or irritability.[2]

- Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) measures the how fast signals travel along a nerve. The nerve signals are measured with surface electrodes (similar to those used for an electrocardiogram) or needle electrodes. FSHD does not affect nerve conduction velocity; abnormal nerve conduction would point towards a neuropathy rather than myopathy.[citation needed]

- Muscle biopsy is the surgical removal and examination of a small piece of muscle, usually from the arm or leg. Microscopy and a variety of biochemical tests are used for examination. Findings in FSHD are nonspecific, such as presence of white blood cells or variation in muscle fiber size. This test is rarely indicated.[2]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sensitive for detecting muscle damage, even in mild cases. T1-weighted MRI imaging can visualize fatty infiltration of muscles, and T2-weighted MRI imaging can visualize muscle edema.[citation needed] MRI can help differentiate FSHD from other muscle diseases on the basis of the pattern of muscles involved, directing genetic testing.[37][38]

- Ultrasound (US) can be used in the evaluation of muscles.[98] US is effective at identifying fatty infiltration or scarring of muscles due to FSHD, manifesting as increased echogenicity (appearing brighter on ultrasound imaging).[98] Advantages of US, compared to MRI or computed tomography, include low cost and no radiation exposure. However, US has poorer evaluation of deeper muscles, and ultrasonic findings tend to be more operator-dependent.[98]

- Computed tomography (CT) imaging is not routinely used for muscle imaging due to significant radiation exposure and inferior characterization of soft tissues (ie, parts of the body other than bone).[98] However, muscle that is incidentally imaged by CT can appear atrophied and lower density, because fat is less dense than muscle.[98] CT has limited ability to detect the inflammatory changes of muscle that MRI can detect.[98]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Included in the differential diagnosis of FSHD are limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (especially calpainopathy),[2] scapuloperoneal myopathy,[99] mitochondrial myopathy,[2] Pompe disease,[2] and polymyositis.[2] Calpainopathy and scapuloperoneal myopathy, like FSHD, present with scapular winging.[99] Features that suggest FSHD are facial weakness, asymmetric weakness, and lack of benefit from immunosuppression medications.[2] Features the suggest an alternative diagnosis are contractures, respiratory insufficiency, weakness of muscles controlling eye movement, and weakness of the tongue or throat.[14]

Management

[edit]No pharmacologic treatment has proven to significantly slow progression of weakness or meaningfully improve strength.[100][2][10]

Screening and monitoring of complications

[edit]The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends several medical tests to detect complications of FSHD.[100] A dilated eye exam to look for retinal abnormalities is recommended in those newly diagnosed with FSHD; for those with large D4Z4 deletions, an evaluation by a retinal specialist is recommended yearly.[101][2] A hearing test is recommended for individuals with early-onset FSHD prior to starting school, or for any other FSHD-affected individual with symptoms of hearing loss.[101][2] Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is recommended in those newly diagnosed to establish baseline pulmonary function,[2] and recurrently for those with pulmonary insufficiency symptoms or risks.[101][2] Routine screening for heart conditions, such as through an electrocardiogram (EKG) or echocardiogram (echo), is considered unnecessary in those without symptoms of heart disease.[100]

Physical and occupational therapy

[edit]Aerobic exercise has been shown to reduce chronic fatigue and decelerate fatty infiltration of muscle in FSHD.[102][103] Physical activity in general might slow disease progression in the legs.[10] The AAN recommends that people with FSHD engage in low-intensity aerobic exercise to promote energy levels, muscle health, and bone health.[2] Moderate-intensity strength training appears to do no harm, although it has not been shown to be beneficial.[104] Physical therapy can address specific symptoms; there is no standardized protocol for FSHD. Anecdotal reports suggest that appropriately applied kinesiology tape can reduce pain.[105] Occupational therapy can be used for training in activities of daily living (ADLs) and to help adapt to new assistive devices. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to reduce chronic fatigue in FSHD, and it also decelerates fatty infiltration of muscle when directed towards increasing daily activity.[102][103]

Braces are often used to address muscle weakness. Scapular bracing can improve scapular positioning, which improves shoulder function, although it is often deemed as ineffective or impractical.[106] Ankle-foot orthoses can improve walking, balance, and quality of life.[107]

Pharmacologic management

[edit]No pharmaceuticals have definitively proven effective for altering the disease course.[100] Although a few pharmaceuticals have shown improved muscle mass in limited respects, they did not improve quality of life, and the AAN recommends against their use for FSHD.[100]

Reconstructive surgery

[edit]Scapular winging is amenable to surgical correction, namely operative scapular fixation. Scapular fixation is restriction and stabilization of the position of the scapula, putting it in closer apposition to the rib cage and reducing winging. Absolute restriction of scapular motion by fixation of the scapula to the ribs is most commonly reported.[108] This procedure often involves inducing bony fusion, called arthrodesis, between the scapula and ribs. Names for this include scapulothoracic fusion, scapular fusion, and scapulodesis. This procedure increases arm active range of motion, improves arm function, decreases pain, and improves cosmetic appearance.[109][110] Active range of motion of the arm increases most in the setting of severe scapular winging with an unaffected deltoid muscle;[11] however, passive range of motion decreases. In other words, the patient gains the ability to slowly raise their arms to 90+ degrees, but they lose the ability to "throw" their arm up to a full 180 degrees.[2] The AAN states that scapular fixation can be offered cautiously to select patients after balancing these benefits against the adverse consequences of surgery and prolonged immobilization.[100][10]

Another form of operative scapular fixation is scapulopexy. "Scapulo-" refers to the scapula bone, and "-pexy" is derived from the Greek root "to bind." Some versions of scapulopexy accomplish essentially the same result as scapulothoracic fusion, but instead of inducing bony fusion, the scapula is secured to the ribs with only wire, tendon grafts, or other material. Some versions of scapulopexy do not completely restrict scapular motion, examples including tethering the scapula to the ribs, vertebrae, or other scapula.[108][111] Scapulopexy is considered to be more conservative than scapulothoracic fusion, with reduced recovery time and less effect on breathing.[108] However, they also seem more susceptible to long-term failure.[108] Another form of scapular fixation, although not commonly done in FSHD, is tendon transfer, which involves surgically rearranging the attachments of muscles to bone.[108][112][113] Examples include pectoralis major transfer and the Eden–Lange procedure.

Various other surgical reconstructions have been described. Upper eyelid gold implants have been used for those unable to close their eyes.[114] Drooping lower lip has been addressed with plastic surgery.[115] Ability to smile can theoretically be restored with a tendon transfer, with donors such as a portion of the temporalis muscle, although evidence is lacking in FSHD.[116] Select cases of foot drop can be surgically corrected with tendon transfer, in which the tibialis posterior muscle is repurposed as a tibialis anterior muscle, a version of this being called the Bridle procedure.[117][118][105] Severe scoliosis caused by FSHD can be corrected with spinal fusion; however, since scoliosis might be a compensatory change in response to muscle weakness, correction of spinal alignment can result in further impaired muscle function.

- Scapular winging management

-

Kinesiology tape applied across the scapulas

-

A cloth brace to hold the scapulas in retraction to reduce shoulder symptoms, such as collarbone pain

-

Scapula-to-scapula scapulopexy, pre- and post-operation. The scapulas are tethered together into a retracted position with an Achilles tendon graft, which, in this case, rendered the rhomboid major muscles distinguishable.

Prognosis

[edit]Genetics partially predicts prognosis.[100] Those with large D4Z4 repeat deletions (with a remaining D4Z4 repeat array size of 10–20 kbp, or 1–4 repeats) are more likely to have severe and early disease, as well as non-muscular symptoms.[100] Those who have the genetic mutations of both FSHD1 and FSHD2 are more likely to have severe disease.[74] It has also been observed that D4Z4 shortening is less and disease manifestation is milder when a prominent family history is present, as opposed to a new mutation.[119] In some large families, 30% of those with the mutation had no noticeable symptoms, and 30% of those with symptoms did not progress beyond facial and shoulder weakness.[24] Women tend to develop symptoms later in life and have less severe disease courses.[113]

Remaining variations in disease course are attributed to unknown environmental factors. A single study found that disease course is not worsened by tobacco smoking or alcohol consumption, common risk factors for other diseases.[120]

Pregnancy

[edit]Pregnancy outcomes are overall good in mothers with FSHD; there is no difference in rate of preterm labor, rate of miscarriage, and infant outcomes.[121] However, weakness can increase the need for assisted delivery.[121]

A single review found that weakness worsens, without recovery, in 12% of mothers with FSHD during pregnancy, although this might be due to weight gain or deconditioning.[121]

Epidemiology

[edit]The prevalence of FSHD ranges from 1 in 8,333 to 1 in 15,000.[2] The Netherlands reports a prevalence of 1 in 8,333, after accounting for the undiagnosed.[122] The prevalence in the United States is commonly quoted as 1 in 15,000.[15]

After genetic testing became possible in 1992, average prevalence was found to be around 1 in 20,000, a large increase compared to before 1992.[123][24][122] However, 1 in 20,000 is likely an underestimation, since many with FSHD have mild symptoms and are never diagnosed, or they are siblings of affected individuals and never seek definitive diagnosis.[122]

Race and ethnicity have not been shown to affect FSHD incidence or severity.[15]

Although the inheritance of FSHD shows no predilection for biological sex, the disease manifests less often in women, and even when it manifests in women, they on average are less severely affected than affected males.[15] Estrogen has been suspected to be a protective factor that accounts for this discrepancy. One study found that estrogen reduced DUX4 activity.[124] However, another study found no association between disease severity and lifetime estrogen exposure in females. The same study found that disease progression was not different through periods of hormonal changes, such as menarche, pregnancy, and menopause.[125]

History

[edit]The first description of a person with FSHD in medical literature appears in an autopsy report by Jean Cruveilhier in 1852.[16][17] In 1868, Duchenne published his seminal work on Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and as part of its differential was a description of FSHD.[126][17] First in 1874, then with a more commonly cited publication in 1884, and again with pictures in 1885, the French physicians Louis Landouzy and Joseph Dejerine published details of the disease, recognizing it as a distinct clinical entity, and thus FSHD is sometimes referred to as Landouzy Dejerine disease.[18][17] In their paper of 1886, Landouzy and Dejerine drew attention to the familial nature of the disorder and mentioned that four generations were affected in the kindred that they had investigated.[127] Formal definition of FSHD's clinical features did not occur until 1952 when a large Utah family with FSHD was studied. Beginning about 1980 an increasing interest in FSHD led to increased understanding of the great variability in the disease and a growing understanding of the genetic and pathophysiological complexities. By the late 1990s, researchers were finally beginning to understand the regions of chromosome 4 associated with FSHD.[53]

Since the publication of the unifying theory in 2010, researchers continued to refine their understanding of DUX4. With increasing confidence in this work, researchers proposed the first a consensus view in 2014 of the pathophysiology of the disease and potential approaches to therapeutic intervention based on that model.[27]

Alternate and historical names for FSHD include the following:

- facioscapulohumeral disease[23]

- faciohumeroscapular [citation needed]

- Landouzy–Dejerine disease[23] (or 'syndrome'[127] or 'type of muscular dystrophy'[23])

- Erb-Landouzy-Dejerine syndrome[citation needed]

Chronology of important FSHD-related genetic research

[edit]| 1861 | Person with muscular dystrophy depicted by Duchenne. Based on the muscles involved, this person could have had FSHD. |

| 1884 | Landouzy and Dejerine describe a form of childhood progressive muscle atrophy with a characteristic involvement of facial muscles and distinct from pseudohypertrophic (Duchenne's MD) and spinal muscle atrophy in adults.[128]

Two brothers with FSHD followed by Landouzy and Dejerine Photograph of one brother at age 21. The right scapula is protracted, downwardly rotated, and laterally displaced. Drawing of another brother at age 17. Visible is lumbar hyperlordosis. The upper arm and pectoral muscles appear atrophied. |

| 1886 | Landouzy and Dejerine describe progressive muscular atrophy of the scapulo-humeral type.[129] |

| 1950 | Tyler and Stephens study 1249 individuals from a single kindred with FSHD traced to a single ancestor and describe a typical Mendelian inheritance pattern with complete penetrance and highly variable expression. The term facioscapulohumeral dystrophy is introduced.[130] |

| 1982 | Padberg provides the first linkage studies to determine the genetic locus for FSHD in his seminal thesis "Facioscapulohumeral disease."[23] |

| 1987 | The complete sequence of the Dystrophin gene (Duchenne's MD) is determined.[131] |

| 1991 | The genetic defect in FSHD is linked to a region (4q35) near the tip of the long arm of chromosome 4.[132] |

| 1992 | FSHD, in both familial and de novo cases, is found to be linked to a recombination event that reduces the size of 4q EcoR1 fragment to < 28 kb (50–300 kb normally).[93] |

| 1993 | 4q EcoR1 fragments are found to contain tandem arrangement of multiple 3.3-kb units (D4Z4), and FSHD is associated with the presence of < 11 D4Z4 units.[92]

A study of seven families with FSHD reveals evidence of genetic heterogeneity in FSHD.[133] |

| 1994 | The heterochromatic structure of 4q35 is recognized as a factor that may affect the expression of FSHD, possibly via position-effect variegation.[134]

DNA sequencing within D4Z4 units shows they contain an open reading frame corresponding to two homeobox domains, but investigators conclude that D4Z4 is unlikely to code for a functional transcript.[134][135] |

| 1995 | The terms FSHD1A and FSHD1B are introduced to describe 4q-linked and non-4q-linked forms of the disease.[136] |

| 1996 | FSHD Region Gene1 (FRG1) is discovered 100 kb proximal to D4Z4.[137] |

| 1998 | Monozygotic twins with vastly different clinical expression of FSHD are described.[20] |

| 1999 | Complete sequencing of 4q35 D4Z4 units reveals a promoter region located 149 bp 5' from the open reading frame for the two homeobox domains, indicating a gene that encodes a protein of 391 amino acid protein (later corrected to 424 aa[138]), given the name DUX4.[139] |

| 2001 | Investigators assessed the methylation state (heterochromatin is more highly methylated than euchromatin) of DNA in 4q35 D4Z4. An examination of SmaI, MluI, SacII, and EagI restriction fragments from multiple cell types, including skeletal muscle, revealed no evidence for hypomethylation in cells from FSHD1 patients relative to D4Z4 from unaffected control cells or relative to homologous D4Z4 sites on chromosome 10. However, in all instances, D4Z4 from sperm was hypomethylated relative to D4Z4 from somatic tissues.[140] |

| 2002 | A polymorphic segment of 10 kb directly distal to D4Z4 is found to exist in two allelic forms, designated 4qA and 4qB. FSHD1 is associated solely with the 4qA allele.[141]

Three genes (FRG1, FRG2, ANT1) located in the region just centromeric to D4Z4 on chromosome 4 are found in isolated muscle cells from individuals with FSHD at levels 10 to 60 times greater than normal, showing a linkage between D4Z4 contractions and altered expression of 4q35 genes.[142] |

| 2003 | A further examination of DNA methylation in different 4q35 D4Z4 restriction fragments (BsaAI and FseI) showed significant hypomethylation at both sites for individuals with FSHD1, non-FSHD-expressing gene carriers, and individuals with phenotypic FSHD relative to unaffected controls.[143] |

| 2004 | Contraction of the D4Z4 region on the 4qB allele to < 38 kb does not cause FSHD.[144] |

| 2006 | Transgenic mice overexpressing FRG1 are shown to develop severe myopathy.[145] |

| 2007 | The DUX4 open reading frame is found to have been conserved in the genome of primates for over 100 million years, supporting the likelihood that it encodes a required protein.[146]

Researchers identify DUX4 mRNA in primary FSHD myoblasts and identify in D4Z4-transfected cells a DUX4 protein, the overexpression of which induces cell death.[138] DUX4 mRNA and protein expression are reported to increase in myoblasts from FSHD patients, compared to unaffected controls. Stable DUX4 mRNA is transcribed only from the most distal D4Z4 unit, which uses an intron and a polyadenylation signal provided by the flanking pLAM region. DUX4 protein is identified as a transcription factor, and evidence suggests overexpression of DUX4 is linked to an increase in the target paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PITX1).[147] |

| 2009 | The terms FSHD1 and FSHD2 are introduced to describe D4Z4-deletion-linked and non-D4Z4-deletion-linked genetic forms, respectively. In FSHD1, hypomethylation is restricted to the short 4q allele, whereas FSHD2 is characterized by hypomethylation of both 4q and both 10q alleles.[148]

Splicing and cleavage of the terminal (most telomeric) 4q D4Z4 DUX4 transcript in primary myoblasts and fibroblasts from FSHD patients is found to result in the generation of multiple RNAs, including small noncoding RNAs, antisense RNAs and capped mRNAs as new candidates for the pathophysiology of FSHD.[149] Mechanism proposed of DBE-T (D4Z4 Regulatory Element transcript) leading to de-repression of 4q35 genes.[62] |

| 2010 | A unifying genetic model of FSHD is established: D4Z4 contractions only cause FSHD when in the context of a 4qA allele due to stabilization of DUX4 RNA transcript, allowing DUX4 expression.[8] Several organizations including The New York Times highlighted this research[150][151]

Francis Collins, who oversaw the first sequencing of the Human Genome with the National Institutes of Health stated:[150]

Daniel Perez, co-founder of the FSHD Society, hailed the new findings saying:[151]

The MDA stated that:[citation needed]

One of the report's co-authors, Silvère van der Maarel of the University of Leiden, stated that[citation needed]

DUX4 is found actively transcribed in skeletal muscle biopsies and primary myoblasts. FSHD-affected cells produce a full-length transcript, DUX4-fl, whereas alternative splicing in unaffected individuals results in the production of a shorter, 3'-truncated transcript (DUX4-s). The low overall expression of both transcripts in muscle is attributed to relatively high expression in a small number of nuclei (~ 1 in 1000). Higher levels of DUX4 expression in human testis (~100 fold higher than skeletal muscle) suggest a developmental role for DUX4 in human development. Higher levels of DUX4-s (vs DUX4-fl) are shown to correlate with a greater degree of DUX-4 H3K9me3-methylation.[7] |

| 2012 | Some instances of FSHD2 are linked to mutations in the SMCHD1 gene on chromosome 18, and a genetic/mechanistic intersection of FSHD1 and FSHD2 is established.[68]

The prevalence of FSHD-like D4Z4 deletions on permissive alleles is significantly higher than the prevalence of FSHD in the general population, challenging the criteria for molecular diagnosis of FSHD.[152] When expressed in primary myoblasts, DUX4-fl acted as a transcriptional activator, producing a > 3-fold change in the expression of 710 genes.[153] A subsequent study using a larger number of samples identified DUX4-fl expression in myogenic cells and muscle tissue from unaffected relatives of FSHD patients, per se, is not sufficient to cause pathology, and that additional modifiers are determinants of disease progression.[154] |

| 2013 | Mutations in SMCHD1 are shown to increase the severity of FSHD1.[74]

Transgenic mice carrying D4Z4 arrays from an FSHD1 allele (with 2.5 D4Z4 units), although lacking an obvious FSHD-like skeletal muscle phenotype, are found to recapitulate important genetic expression patterns and epigenetic features of FSHD.[155] |

| 2014 | DUX4-fl and downstream target genes are expressed in skeletal muscle biopsies and biopsy-derived cells of fetuses with FSHD-like D4Z4 arrays, indicating that molecular markers of FSHD are already expressed during fetal development.[156]

Researchers "review how the contributions from many labs over many years led to an understanding of a fundamentally new mechanism of human disease" and articulate how the unifying genetic model and subsequent research represent a "pivot-point in FSHD research, transitioning the field from discovery-oriented studies to translational studies aimed at developing therapies based on a sound model of disease pathophysiology." They describe the consensus mechanism of pathophysiology for FSHD as an "inefficient repeat-mediated epigenetic repression of the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array on chromosome 4, resulting in the variegated expression of the DUX4 retrogene, encoding a double-homeobox transcription factor, in skeletal muscle."[27] |

| 2020 | Voice of the Patient Report released documenting FSHD's impacts on daily life as conveyed by about 400 patients during an FDA externally led Patient-Focused Drug Development meeting, which was held on June 29, 2020.[32][30][31][33] |

Past pharmaceutical development

[edit]Early drug trials, before the pathogenesis involving DUX4 was discovered, were untargeted and largely unsuccessful.[19] Compounds were trialed with goals of increasing muscle mass, decreasing inflammation, or addressing provisional theories of disease mechanism.[19] The following drugs failed to show efficacy:

- Prednisone, a steroid, based on its antiinflammatory properties and therapeutic effect in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[157]

- Oral albuterol, a β2 agonist, on the basis of its anabolic properties. Although it improved muscle mass and certain measures of strength in those with FSHD, it did not improve global strength or function.[158][159][160] Interestingly, β2 agonists were later shown to reduce DUX4 expression.[161]

- Diltiazem, a calcium channel blocker, on the bases of anecdotal reports of benefit and the theory that calcium dysregulation played a part in muscle cell death.[162]

- MYO-029 (stamulumab), an antibody that inhibits myostatin, was developed to promote muscle growth. Myostatin is a protein that inhibits the growth of muscle tissue.[163]

- ACE-083, a TGF-β inhibitor, was developed to promote muscle growth.[164]

Society and culture

[edit]Media

[edit]- In the Amazon Video series The Man in the High Castle, Obergruppenführer John Smith's son, Thomas, is diagnosed with Landouzy–Dejerine syndrome.[165]

- In the biography Stuart: A Life Backwards, the protagonist was affected by muscular dystrophy,[166] presumably FSHD.[citation needed]

- Good Bad Things, an independent film about an entrepreneur afflicted with FSHD and his journey of transformation, self-acceptance and discovery. The movie premiered at the 2024 Slamdance Film Festival[167][168]

- The Lost Voice, a short film featuring Tristram Ingham who lives with FSHD. Ingham used Apple's Personal Voice feature to recreate his voice and use it to read a children's book titled The Lost Voice for International Day of Persons with Disabilities in 2023.[169]

Patient and research organizations

[edit]- The FSHD Society (named "FSH Society" until 2019)[170] was founded in 1991 on the East Coast by two individuals with FSHD, Daniel Perez and Stephen Jacobsen.[171][172] The FSHD Society claims to have advocated for the standardization of the disease name facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and its abbreviation FSHD.[170] The FSHD Society claims to have raised funding for seed grants for FSHD research and co-wrote the MD-CARE Act of 2001, which provided federal funding for all muscular dystrophies.[171][172] The FSHD Society has grown into the world's largest grassroots organization advocating for patient education and scientific and medical research for FSHD.[173][174] One notable spokesperson for FSHD Society has been Max Adler, an actor on the TV series Glee.[175]

- Friends of FSH Research is a research-oriented nonprofit organization founded in 2004 by Terry and Rick Colella from Kirkland, Washington, after their son was diagnosed with FSHD.[176][177][178][179]

- The FSHD Global Research Foundation was founded in 2007 by Bill Moss in Australia, a former Macquarie Bank executive affected by FSHD.[180][181][182] It is currently directed by Moss's daughter.[181] It was named Australian charity of the year for 2017.[181] It is the largest funder of FSHD medical research outside of the United States as of 2018.[182]

- FSHD EUROPE was founded in 2010.[183] Spanning multiple countries in Europe, it has launched the European Trial Network.[183]

Notable cases

[edit]- Chip Wilson is a Canadian billionaire and founder of Lululemon. He has pledged 100 million Canadian dollars to research through the venture 'Solve FSHD'.[184]

- Chris Carrino is the radio voice of the Brooklyn Nets. He founded the Chris Carrino Foundation for FSHD, oriented towards research funding.[185]

- Madison Ferris is an American actress with FSHD who was the first wheelchair user to play a lead on Broadway.[186][187]

- Morgan Hoffmann is an American professional golfer. He started the Morgan Hoffmann Foundation, oriented towards research funding.[188]

- Arnold Gold (1925–2024) was a pediatric neurologist, founder of the Arnold P. Gold Foundation, and creator of white coat ceremonies. Gold focused on patient-centered care and humanism.[189]

Research directions

[edit]Pharmaceutical development

[edit]After achieving consensus on FSHD pathophysiology in 2014, researchers proposed four approaches for therapeutic intervention:[27]

- enhance the epigenetic repression of the D4Z4

- target the DUX4 mRNA, including altering splicing or polyadenylation;

- block the activity of the DUX4 protein

- inhibit the DUX4-induced process, or processes, that leads to pathology.

Small molecule drugs

Most drugs used in medicine are "small molecule drugs," as opposed to biologic medical products that include proteins, vaccines, and nucleic acids. Small molecule drugs can typically be taken by ingestion, rather than injection.

- Losmapimod, a selective inhibitor of p38α/β mitogen-activated protein kinases, was identified by Fulcrum Therapeutics as a potent suppressor of DUX4 in vitro.[191] Results of a phase IIb clinical trial, revealed in June 2021, showed statistically significant slowing of muscle function deterioration. Further trials are pending.[192][193]

- Casein kinase 1 (CK1) inhibition has been identified by Facio Therapies, a Dutch pharmaceutical company, to repress DUX4 expression and is in preclinical development. Facio Therapies claims that CK1 inhibition leaves myotube fusion intact, unlike BET inhibitors, p38 MAPK inhibitors, and β2 agonists.[194][195]

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is the administration of nucleotides to treat disease. Multiple types of gene therapy are in the preclinical stage of development for the treatment of FSHD.

- Antisense therapy utilizes antisense oligonucleotides that bind to DUX4 messenger RNA, inducing its degradation and preventing DUX4 protein production[196][197]. Phosphorodiamidate morpholinos, an oligonucleotide modified to increase its stability, have been shown to selectively reduce DUX4 and its effects; however, these antisense nucleotides have poor ability to penetrate muscle.[2]

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs) directed against DUX4, delivered by viral vectors, have shown to reduce DUX4, protect against muscle pathology, and prevent loss of grip strength in mouse FSHD models.[2] Arrowhead pharmaceuticals is developing an RNA interference therapeutic against DUX4, named ARO-DUX4, and intends to file for regulatory clearance in third quarter of 2021 to begin clinical trials.[198][199][200]

- Genome editing, the permanent alteration of genetic code, is being researched. One study tried to use CRISPR-Cas9 to knockout the polyadenylation signal in lab dish models, but was unable to show therapeutic results.[201]

Potential drug targets

- Inhibition of the hyaluronic acid (HA) pathway is a potential therapy. One study found that many DUX4-induced molecular pathologies are mediated by HA signaling, and inhibition of HA biosynthesis with 4-methylumbelliferone prevented these molecular pathologies.[202]

- P300 inhibition has shown to inhibit the deleterious effects of DUX4[203]

- BET inhibitors have been shown to reduce DUX4 expression.[161]

- Antioxidants could potentially reduce the effects of FSHD. One study found that vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc gluconate, and selenomethionine supplementation increased endurance and strength of the quadriceps, but had no significant benefit on walking performance.[204] Further study is warranted.[2]

Outcome measures

[edit]Ways of measuring the disease are important for studying disease progression and assessing the efficacy of drugs in clinical trials.

- Reachable workspace uses the Kinect motion sensing system to compare range of reach before and after a therapeutic clinical trial.[205]

- Quality of life can be measured with questionnaires, such as the FSHD Health Index.[206][2]

- How the disease affects daily activities can measured with questionnaires, such as the FSHD‐Rasch‐built overall disability scale (FSHD-RODS)[207] or FSHD composite outcome measure (FSHD-COM).[208]

- Electrical impedance myography is being studied as a way to measure muscle damage.[2]

- Muscle MRI is useful for assessment of all the muscles in the body. Muscles can be scored based on the degree of fat infiltration.[2]

References

[edit]- ^

The sources listed below differ on pronunciation of the 'u' in 'scapulo'. A 'long u' sound in an unstressed nonfinal syllable is often reduced to a schwa and varies by speaker.

- "Facioscapulohumeral". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- "Facioscapulohumeral". Medical Dictionary, Farlex and Partners, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw Wagner KR (December 2019). "Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophies". CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 25 (6): 1662–1681. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000801. PMID 31794465. S2CID 208531681.

- ^ Stedman T (1987). Webster's New World/Stedman's Concise Medical Dictionary (1 ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 230. ISBN 0-13-948142-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Mul K, Lassche S, Voermans NC, Padberg GW, Horlings CG, van Engelen BG (June 2016). "What's in a name? The clinical features of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Practical Neurology. 16 (3): 201–207. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2015-001353. PMID 26862222. S2CID 4481678.

- ^ a b Kumar V, Abbas A, Aster J, eds. (2018). Robbins Basic Pathology (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier. p. 844. ISBN 978-0-323-35317-5.

- ^ De Iaco A, Planet E, Coluccio A, Verp S, Duc J, Trono D (June 2017). "DUX-family transcription factors regulate zygotic genome activation in placental mammals". Nature Genetics. 49 (6): 941–945. doi:10.1038/ng.3858. PMC 5446900. PMID 28459456.

- ^ a b c Snider L, Geng LN, Lemmers RJ, Kyba M, Ware CB, Nelson AM, Tawil R, Filippova GN, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ, Miller DG (28 October 2010). "Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: incomplete suppression of a retrotransposed gene". PLOS Genetics. 6 (10): e1001181. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001181. PMC 2965761. PMID 21060811.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lemmers RJ, van der Vliet PJ, Klooster R, Sacconi S, Camaño P, Dauwerse JG, Snider L, Straasheijm KR, van Ommen GJ, Padberg GW, Miller DG, Tapscott SJ, Tawil R, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM (19 August 2010). "A Unifying Genetic Model for Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy" (PDF). Science. 329 (5999): 1650–3. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1650L. doi:10.1126/science.1189044. hdl:1887/117104. PMC 4677822. PMID 20724583. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-05.

- ^ a b Lemmers RJ, Wohlgemuth M, van der Gaag KJ, et al. (November 2007). "Specific sequence variations within the 4q35 region are associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81 (5): 884–94. doi:10.1086/521986. PMC 2265642. PMID 17924332.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mul K (1 December 2022). "Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 28 (6): 1735–1751. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000001155. PMID 36537978. S2CID 254883066.

- ^ a b Eren İ, Birsel O, Öztop Çakmak Ö, Aslanger A, Gürsoy Özdemir Y, Eraslan S, Kayserili H, Oflazer P, Demirhan M (May 2020). "A novel shoulder disability staging system for scapulothoracic arthrodesis in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy". Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 106 (4): 701–707. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2020.03.002. PMID 32430271.

- ^ Theadom A, Rodrigues M, Roxburgh R, Balalla S, Higgins C, Bhattacharjee R, Jones K, Krishnamurthi R, Feigin V (2014). "Prevalence of muscular dystrophies: a systematic literature review". Neuroepidemiology. 43 (3–4): 259–68. doi:10.1159/000369343. hdl:10292/13206. PMID 25532075. S2CID 2426923.

- ^ Mah JK, Korngut L, Fiest KM, Dykeman J, Day LJ, Pringsheim T, Jette N (January 2016). "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on the Epidemiology of the Muscular Dystrophies". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 43 (1): 163–77. doi:10.1017/cjn.2015.311. PMID 26786644. S2CID 24936950.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tawil R, Van Der Maarel SM (July 2006). "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy" (PDF). Muscle & Nerve. 34 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1002/mus.20522. PMID 16508966. S2CID 43304086.

- ^ a b c d Statland JM, Tawil R (December 2016). "Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 22 (6, Muscle and Neuromuscular Junction Disorders): 1916–1931. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000399. PMC 5898965. PMID 27922500.

- ^ a b Cruveilhiers J (1852–1853). "Mémoire sur la paralysie musculaire atrophique". Bulletins de l'Académie de Médecine. 18: 490–502, 546–583.

- ^ a b c d Rogers MT (2004). "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: historical background and literature review". In Upadhyaya M, Cooper DN (eds.). FSHD facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: clinical medicine and molecular cell biology. BIOS Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-85996-244-0.

- ^ a b Landouzy L, Dejerine J (1885). Landouzy L, Lépine R (eds.). "De la myopathie atrophique progressive (myopathie sans neuropathie débutant d'ordinaire dans l'enfance par la face)". Revue de Médecine (in French). 5. Felix Alcan: 253–366. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Cohen J, DeSimone A, Lek M, Lek A (October 2020). "Therapeutic Approaches in Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 27 (2): 123–137. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.09.008. PMC 8048701. PMID 33092966.

- ^ a b Tupler R, Barbierato L, et al. (Sep 1998). "Identical de novo mutation at the D4F104S1 locus in monozygotic male twins affected by facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) with different clinical expression". Journal of Medical Genetics. 35 (9): 778–783. doi:10.1136/jmg.35.9.778. PMC 1051435. PMID 9733041.

- ^ Tawil R, Storvick D, Feasby TE, Weiffenbach B, Griggs RC (February 1993). "Extreme variability of expression in monozygotic twins with FSH muscular dystrophy". Neurology. 43 (2): 345–8. doi:10.1212/wnl.43.2.345. PMID 8094896. S2CID 44422140.

- ^ Pandya S, Eichinger K. "Physical Therapy for Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy" (PDF). FSHD Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Padberg GW (1982-10-13). Facioscapulohumeral disease (Thesis). Leiden University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Padberg GW (2004). "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: a clinician's experience". In Upadhyaya M, Cooper DN (eds.). FSHD Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy: Clinical Medicine and Molecular Cell Biology. BIOS Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-85996-244-0.

- ^ a b c Rijken NH, van der Kooi EL, Hendriks JC, van Asseldonk RJ, Padberg GW, Geurts AC, van Engelen BG (December 2014). "Skeletal muscle imaging in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, pattern and asymmetry of individual muscle involvement". Neuromuscular Disorders. 24 (12): 1087–96. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2014.05.012. PMID 25176503. S2CID 101093.

- ^ Bergsma A, Cup EH, Janssen MM, Geurts AC, de Groot IJ (February 2017). "Upper limb function and activity in people with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: a web-based survey". Disability and Rehabilitation. 39 (3): 236–243. doi:10.3109/09638288.2016.1140834. PMID 26942834. S2CID 4237308.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tawil R, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ (10 June 2014). "Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: the path to consensus on pathophysiology". Skeletal Muscle. 4 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/2044-5040-4-12. PMC 4060068. PMID 24940479.

- ^ Jia FF, Drew AP, Nicholson GA, Corbett A, Kumar KR (2 October 2021). "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2: an update on the clinical, genetic, and molecular findings". Neuromuscular Disorders. 31 (11): 1101–1112. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2021.09.010. PMID 34711481. S2CID 238246093.

- ^ a b Upadhyaya M, Cooper D, eds. (March 2004). FSHD Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy: Clinical Medicine and Molecular Cell Biology. BIOS Scientific Publishers. ISBN 0-203-48367-7.

- ^ a b The FDA held an externally-led Patient-Focused Drug Development meeting with about 400 FSHD patients on June 29, 2020, resulting in a seminal document called the "Voice of the Patient Report." The report captures the impact of FSHD on the daily lives of those with the disease as conveyed by the patients themselves. While FSHD is often perceived to be "mild," the report shows that over 80% of patients report being "moderately" or "severely" limited in daily activities.

- Society F. "FSHD Society releases Voice of the Patient Report on FSH muscular dystrophy". PRWeb. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Society F. "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy community speaks to the FDA". PRWeb. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Voice of the Patient Forum - Patient-Focused Drug Development Meeting, 29 June 2020, retrieved 2024-01-31

- ^ a b Overman D (2020-11-13). "People Living with FSHD Tell Their Stories in New Report". Rehab Management. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Mul K, Berggren KN, Sills MY, McCalley A, van Engelen B, Johnson NE, Statland JM (26 February 2019). "Effects of weakness of orofacial muscles on swallowing and communication in FSHD". Neurology. 92 (9): e957 – e963. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007013. PMC 6404471. PMID 30804066.

- ^ Wohlgemuth M, de Swart BJ, Kalf JG, Joosten FB, Van der Vliet AM, Padberg GW (27 June 2006). "Dysphagia in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Neurology. 66 (12): 1926–8. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000219760.76441.f8. PMID 16801662. S2CID 7695047.

- ^ a b "A giant of FSHD research shares his "regrets"". FSHD Society. Way Back Machine. 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

Another striking aspect of FSHD is that muscles weakness seems to vary so much from patient to patient. Nonetheless, "there is a highly characteristic pattern of muscle weakness, otherwise we would never have been able to recognize FSHD as a specific disease," Padberg said. "Strong deltoid muscle does not occur in any other condition that involves weakness of scapular stabilizers. No other muscle disease with shoulder girdle involvement has this pattern." Unfortunately, "an explanation is beyond our grasp as we don't know how muscle are laid down" during the early stages of human gestation.

- ^ a b c Tasca G, Monforte M, Iannaccone E, Laschena F, Ottaviani P, Leoncini E, Boccia S, Galluzzi G, Pelliccioni M, Masciullo M, Frusciante R, Mercuri E, Ricci E (2014). "Upper girdle imaging in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e100292. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0292T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100292. PMC 4059711. PMID 24932477.

- ^ a b c Gerevini S, Scarlato M, Maggi L, Cava M, Caliendo G, Pasanisi B, Falini A, Previtali SC, Morandi L (March 2016). "Muscle MRI findings in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". European Radiology. 26 (3): 693–705. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3890-1. PMID 26115655. S2CID 24650482.

- ^ Faux-Nightingale A, Kulshrestha R, Emery N, Pandyan A, Willis T, Philp F (September 2021). "Upper limb rehabilitation in fascioscapularhumeral dystrophy (FSHD): a patients' perspective". Archives of Rehabilitation Research and Clinical Translation. 3 (4): 100157. doi:10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100157. ISSN 2590-1095. PMC 8683863. PMID 34977539.

- ^ Pandya S, King WM, Tawil R (1 January 2008). "Facioscapulohumeral Dystrophy". Physical Therapy. 88 (1): 105–113. doi:10.2522/ptj.20070104. PMID 17986494.

- ^ Liew WK, van der Maarel SM, Tawil R (2015). "Facioscapulohumeral Dystrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders of Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence. pp. 620–630. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-417044-5.00032-9. ISBN 978-0-12-417044-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Goselink R, Schreur V, van Kernebeek CR, Padberg GW, van der Maarel SM, van Engelen B, Erasmus CE, Theelen T (2019). "Ophthalmological findings in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy". Brain Communications. 1 (1): fcz023. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcz023. PMC 7425335. PMID 32954265.

- ^ Padberg GW, Brouwer OF, de Keizer RJ, Dijkman G, Wijmenga C, Grote JJ, Frants RR (1995). "On the significance of retinal vascular disease and hearing loss in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Muscle & Nerve. 18 (S13): S73 – S80. doi:10.1002/mus.880181314. hdl:2066/20764. S2CID 27523889.

- ^ Lindner M, Holz FG, Charbel Issa P (2016-04-27). "Spontaneous resolution of retinal vascular abnormalities and macular oedema in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 44 (7): 627–628. doi:10.1111/ceo.12735. ISSN 1442-6404. PMID 26933772. S2CID 204996841.

- ^ Trevisan CP, Pastorello E, Tomelleri G, Vercelli L, Bruno C, Scapolan S, Siciliano G, Comacchio F (December 2008). "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: hearing loss and other atypical features of patients with large 4q35 deletions". European Journal of Neurology. 15 (12): 1353–8. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02314.x. PMID 19049553. S2CID 26276887.

- ^ a b Eren İ, Abay B, Günerbüyük C, Çakmak ÖÖ, Şar C, Demirhan M (February 2020). "Spinal fusion in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy for hyperlordosis: A case report". Medicine. 99 (8): e18787. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000018787. PMC 7034682. PMID 32080072.

- ^ Huml RA, Perez DP (2015). "FSHD: The Most Common Type of Muscular Dystrophy?". Muscular Dystrophy. pp. 9–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17362-7_3. ISBN 978-3-319-17361-0.

- ^ Wohlgemuth M, van der Kooi EL, van Kesteren RG, van der Maarel SM, Padberg GW (2004). "Ventilatory support in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Neurology. 63 (1): 176–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.543.2968. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000133126.86377.e8. PMID 15249635. S2CID 31335126.

- ^ Dowling JJ, Weihl CC, Spencer MJ (November 2021). "Molecular and cellular basis of genetically inherited skeletal muscle disorders". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 22 (11): 713–732. doi:10.1038/s41580-021-00389-z. PMC 9686310. PMID 34257452. S2CID 235822532.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jagannathan S (1 May 2022). "The evolution of DUX4 gene regulation and its implication for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1868 (5): 166367. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166367. PMC 9173005. PMID 35158020.