Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons | |

|---|---|

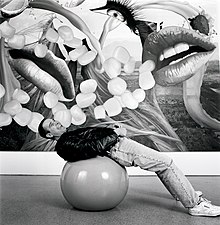

Koons in 2014 | |

| Born | Jeffrey Lynn Koons January 21, 1955 |

| Education | School of the Art Institute of Chicago Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore |

| Known for | Artist |

| Notable work | Rabbit (1986) Puppy (1992) Balloon Dog (1994–2000) |

| Spouses | |

| Website | jeffkoons |

Jeffrey Lynn Koons (/kuːnz/; born January 21, 1955)[1] is an American artist recognized for his work dealing with popular culture and his sculptures depicting everyday objects, including balloon animals produced in stainless steel with mirror-finish surfaces. He lives and works in both New York City and his hometown of York, Pennsylvania. His works have sold for substantial sums, including at least two record auction prices for a work by a living artist: US$58.4 million for Balloon Dog (Orange) in 2013[2] and US$91.1 million for Rabbit in 2019.[3][4]

Critics come sharply divided in their views of Koons. Some view his work as pioneering and of major art-historical importance. Others dismiss his work as kitsch, crass, and based on cynical self-merchandising. Koons has stated that there are no hidden meanings or critiques in his works.[5][6]

Early life

[edit]Koons was born in York, Pennsylvania, to Henry Koons and Nancy Loomis. His father[7] was a furniture dealer and interior decorator. His mother was a seamstress.[8] When he was nine years old, his father would place old master paintings that Koons copied and signed in the window of his shop in an attempt to attract visitors.[9] As a child he went door-to-door after school selling gift-wrapping paper and candy to earn pocket money.[10] As a teenager he revered Salvador Dalí so much that he visited him at the St. Regis Hotel in New York City.[11]

Koons studied painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore before transferring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied from 1975 to 1976.[12][13] While a student at the Art Institute, Koons met the artist Ed Paschke, who became a major influence and for whom Koons worked as a studio assistant in the late 1970s.[14] He lived in Lakeview, and then in the Pilsen neighborhood at Halsted Street and 19th Street.[15]

After college, Koons moved to New York in 1977[16] and worked at the membership desk of the Museum of Modern Art[17] while establishing himself as an artist. During this time, he dyed his hair red and often wore a pencil mustache, after Salvador Dalí.[16] In 1980, he became licensed to sell mutual funds and stocks and began working as a Wall Street commodities broker at First Investors Corporation. After a summer with his parents in Sarasota, Florida, where he briefly worked as a political canvasser, Koons returned to New York and found a new career as a commodities broker, first at Clayton Brokerage Company and then at Smith Barney.[16]

Work

[edit]Following his graduation from the Art Institute in Chicago in 1976, Koons made his way to New York City. There, he moved away from creating representations of his personal fantasies and began to explore objective art, commerce, and politics.[18] He rose to prominence in the mid-1980s as part of a generation of artists who explored the meaning of art in a newly media-saturated era with his Pre-new The New series.[19][18]With recognition came the establishment of a factory-like studio located in a loft at the corner of Houston Street and Broadway in New York in SoHo. It was staffed with over 30 assistants, each assigned to a different aspect of producing his work—in a similar mode as Andy Warhol's Factory. Koons's work is produced using a method known as art fabrication.[20] Until 2019, Koons had a 1,500 m2 (16,000 sq ft) studio factory near the old Hudson rail yards[21] in Chelsea employing 90 to 120[21] assistants to produce his work.[8] More recently, Koons has downsized staffing and shifted to more automated forms of production and relocated to a much smaller studio space.[22] He now uses technology to create his artistic references on computers and color-corrects them until he is satisfied with the results.[23] To ensure consistency, Koons implemented a color-by-numbers system, so that each of his assistants[24] could execute his canvases and sculptures as if they had been done "by a single hand".[7] Throughout his career, he has consistently explored themes such as consumerist behavior, seduction, banality, and childhood, among others.[25]

Early Works and Inflatables

[edit]Jeff Koons first began experimenting with the use of ready-made objects and modes of display in his apartment in 1976. His fascination with the extravagant world of luxurious goods and their more affordable counterparts led him to collect items like toys, metallic finishes, leopard skin, and porcelain.[18] Between 1977 and 1979 Koons produced four separate artworks, which he later referred to as Early Works. In 1978 he began working on his Inflatables series, consisting of inflatable flowers and a rabbit of various heights and colors, positioned along with mirrors.[26] Koons drew inspiration from Robert Smithson's emphasis on display and connected his work to his father's furniture store displays. He documented his work through photography, using it as a means of exploring different installation techniques.[18]

The Pre-New, The New, and Equilibrium series

[edit]Since 1979 Koons has produced work within series.[27] His early work was in the form of conceptual sculpture, an example of which is The Pre-New, a series of domestic objects attached to light fixtures, resulting in strange new configurations. Another example is The New, a series of vacuum-cleaners, often selected for brand names that appealed to the artist like the iconic Hoover, which he had mounted in illuminated Perspex boxes. Koons first exhibited these pieces in the window of the New Museum in New York in 1980. He chose a limited combination of vacuum cleaners and arranged them in cabinets accordingly, juxtaposing the verticality of the upright cleaners with the squat cylinders of the "Shelton Wet/Dry drum" cleaners. At the museum, the machines were displayed as if in a showroom, and oriented around a central red fluorescent lightbox with just the words "The New" written on it as if it were announcing some new concept or marketing brand.[28] They were shown again in a major solo show at Jeff Koons: The New Encased Works at Daniel Weinberg Gallery in 1987.[29]

Another example for Koons's early work is The Equilibrium Series (1983), consisting of one to three basketballs floating in distilled water, a project the artist had researched with the help of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman.[7] The Total Equilibrium Tanks are completely filled with distilled water and a small amount of ordinary salt, to assist the hollow balls in remaining suspended in the centre of the liquid. In a second version, the 50/50 Tanks, only half the tank is filled with distilled water, with the result that the balls float half in and half out of the water.[30] In addition, Koons conceived and fabricated five unique works for the Encased series (1983–1993/98), sculptures consisting of stacked sporting balls (four rows of six basketballs each, and one row of six soccer balls) with their original cardboard packaging in glass display case.[31] Also part of the Equilibrium series are posters featuring basketball stars in Nike advertisements and 10 bronze objects, representing lifesaving gear.

Statuary series

[edit]In 1986, Jeff Koons introduced the Statuary series, featuring ten pieces that reimagined his earlier inflatable series from the 1970s. The series aimed to illustrate how art often mirrors self-perception and evolves into decorative expression by presenting a panoramic view of society. The sculptures drew inspiration from historical figures like Louis XIV and Bob Hope, as well as other art historical themes and sources. Through Statuary, Koons redirected his artistic focus toward the concept of artistic taste and the societal role of art.[32][18] He incorporated some readymade objects, including the inflatable rabbit, and transformed them into highly polished stainless-steel pieces. This led to the creation of one of his most iconic works, Rabbit (1986).[18]

There are three identical versions of Rabbit. One version was previously part of art collector Stefan Edlis's personal collection, but it now resides as a gift at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and another in The Broad Museum in Los Angeles.[33] In May 15, 2019, Jeff Koons set a record for most expensive piece sold by a living artist, for the sale of "Rabbit". The third version of the piece was sold at Christie's Auction House for US$80 million which. After including auctioneer's fees, the final sale price of "Rabbit" was US$91,075,000.[3][4]

The Rabbit has since returned to its original soft form, and many times larger at more than 50 feet high, taken to the air. On October 15, 2009, the giant metallic monochrome color rabbit used during the 2007 Macy's Thanksgiving day parade[34] was put on display for Nuit Blanche in the Eaton Centre in Toronto.[35] The other objects of the series combine objects Koons found in souvenir shops and baroque imagery, thereby playing with the distinction between low art and high art.[36]

Luxury and Degradation series and Kiepenkerl

[edit]First shown in Koons's eponymous exhibitions at the short-lived International With Monument Gallery, New York, and at Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1986, the Luxury and Degradation series is a group of works thematically centered on alcohol.[37] This group included a stainless steel travel cocktail cabinet, a Baccarat crystal decanter and other hand-made renderings of alcohol-related paraphernalia, as well as reprinted and framed ads for drinks such as Gordon's Gin ("I Could Go for Something Gordon's"), Hennessy ("Hennessy, The Civilized Way to Lay Down the Law"), Bacardi ("Aquí... el gran sabor del ron Bacardi"), Dewars ("The Empire State of Scotch"), Martell ("I Assume You Drink Martell") and Frangelico ("Stay in Tonight" and "Find a Quiet Table")[38] in seductively intensified colors on canvas[8] Koons appropriated these advertisements and revalued them by recontextualizing them into artworks. They "deliver a critique of traditional advertising that supports Baudrillard's censorious view of the obscene promiscuity of consumer signs".[39] Another work, Jim Beam – J.B. Turner Engine (1986), is based on a commemorative, collectible in bottle in the form of a locomotive that was created by Jim Beam; however, Koons appropriated this model and had it cast in gleaming stainless-steel.[40] The train model cast in steel titled Jim Beam – Baggage Car (1986) even contains Jim Beam bourbon.[41][42] With the Luxury and Degradation series Koons interfered into the realms of the social. He created an artificial and gleaming surface which represented a proletarian luxury. It was interpreted as seduction by simulation because it was fake luxury. Being the producer of this deception brought him to a kind of leadership, as he commented himself.[43]

The same material of stainless steel was used for the statue of Kiepenkerl. After being rebuilt in the 1950s, the figure of the itinerant trader was replaced by Jeff Koons in 1987 for the decennial Skulptur Projekte exhibition. Standing on a central square in Münster, the statue retained a certain cultural power as a nostalgic symbol of the past.[44] During the production process, the foundry where the piece was being made wanted to knock the ceramic shell off too soon, which resulted in the piece being bent and deformed. Koons decided to bring in a specialist and give the piece "radical plastic surgery." After this experience he felt liberated: "I was now free to work with objects that did not necessarily pre-exist. I could create models."[45]

Banality series

[edit]Koons then moved on to the Banality series. For this project he engaged workshops in Germany and Italy that had a long tradition of working in ceramic, porcelain, and wood.[16] The series culminated in 1988 with Michael Jackson and Bubbles, a series of three life-size gold-leaf plated porcelain statues of the sitting singer cuddling Bubbles, his pet chimpanzee. Three years later, one of these sold at Sotheby's New York for US$5.6 million.[46] Two of these sculptures are now at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) in downtown Los Angeles. The statue was included in a 2004 retrospective at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art in Oslo which traveled a year later to the Helsinki City Art Museum. It also featured in his second retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, in 2008. The statue is currently part of the collection at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art at Tjuvholmen in Oslo.[47] His work Christ and the Lamb (1988) has been analyzed as an acknowledgment and critique of the spiritual and meditative power of the Rococo.[48]

Anticipating a less than generous critical response to his 1988 Banality series exhibition, with all of his new objects made in an edition of three,[49] allowing for simultaneous, identical shows at galleries in New York, Cologne, and Chicago, Koons devised the Art Magazine Ads series (1988–1989).[50] Placed in Artforum, Art in America, Flash Art, and Art News, the ads were designed as promotions for his own gallery exhibitions.[51] Koons also issued Signature Plate, an edition for Parkett magazine, with a photographic decal in colors on a porcelain plate with gold-plated rim.[52] Arts journalist Arifa Akbar reported for The Independent that in "an era when artists were not regarded as 'stars', Koons went to great lengths to cultivate his public persona by employing an image consultant". Featuring photographs by Matt Chedgey, Koons placed "advertisements in international art magazines of himself surrounded by the trappings of success" and gave interviews "referring to himself in the third person".[20]

Made in Heaven series

[edit]In 1989, the Whitney Museum and its guest curator Marvin Heiferman asked Koons to make an artwork about the media on a billboard[7] for the show "Image World: Art and Media Culture". The billboard was meant as an advertisement for an unmade movie, entitled Made in Heaven.[53] Koons employed his then-wife Ilona Staller ("Cicciolina") as a model in the shoot that formed the basis of the resulting work for the Whitney, Made in Heaven (1990–1991).[54] Including works with such titles as Dirty Ejaculation and Ilonaʼs Asshole, the series of enormous grainy[55] photographs printed on canvas, glassworks, and sculptures portrayed Koons and Staller in highly explicit sexual positions and created considerable controversy. The paintings of the series reference art from the Baroque and Rococo periods—among others, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher—and also draw upon the breakthroughs of early modern painters as Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet.[56]

The series was first shown at the 1990 Venice Biennale.[57] Koons reportedly destroyed much of the work when Staller took their son Ludwig with her to Italy.[58] In celebration of Made in Heaven's 20th anniversary, Luxembourg & Dayan chose to present a redux edition of the series.[56][59][55] The Whitney Museum also exhibited several of the photographs on canvas in their 2014 retrospective.

Puppy

[edit]

Koons was not among the 44 American artists selected to exhibit their work in Documenta 9 in 1992,[60] but was commissioned by three art dealers to create a piece for nearby Arolsen Castle in Bad Arolsen, Germany. The result was Puppy, a 43 ft (13 m) tall topiary sculpture of a West Highland White Terrier puppy, executed in a variety of flowers (including Marigolds, Begonias, Impatiens, Petunias, and Lobelias)[61] on a transparent color-coated chrome stainless steel substructure. The self-cleaning flowers would grow for the specific length of time that the piece was exhibited.[62] The size and location of Puppy -the courtyard of a baroque palace- acknowledged the mass audience.[63] After the outbreak that followed his Made in Heaven series, Koons decided to make "an image that communicated warmth and love to people."[64] In 1995, in a co-venture between Museum of Contemporary Art, Kaldor Public Art Projects and Sydney Festival,[65] the sculpture was dismantled and re-erected at the Museum of Contemporary Art on Sydney Harbour on a new, more permanent, stainless steel armature with an internal irrigation system. While the Arolsen Puppy had 20,000 plants, the Sydney version held around 60,000.[66]

The piece was purchased in 1997 by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and installed on the terrace outside the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.[67] Before the dedication at the museum, an Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) trio disguised as gardeners attempted to plant explosive-filled flowerpots near the sculpture,[68] but was foiled by Basque police officer Jose María Aguirre, who then was shot dead by ETA members.[69][70] Currently the square in which the statue is placed bears the name of Aguirre. In the summer of 2000, the statue traveled to New York City for a temporary exhibition at Rockefeller Center.[61]

Media mogul Peter Brant and his wife, model Stephanie Seymour, commissioned Koons to create a duplicate of the Bilbao statue Puppy (1993) for their Connecticut estate, the Brant Foundation Art Study Center.[71] In 1998, a miniature version of Puppy was released as a white glazed porcelain vase, in an edition of 3000.[72]

Celebration series

[edit]

Koons's Celebration was to honor the ardently hoped-for return of Ludwig from Rome [citation needed] . The series, consisting of a series of large-scale sculptures and paintings of balloon dogs, Valentine hearts, diamonds, and Easter eggs, was conceived in 1994. Some of the pieces are still being fabricated.[citation needed] Each of the 20 different sculptures in the series comes in five differently colored "unique versions",[74] including the artist's cracked Egg (Blue) which won the 2008 Charles Wollaston Award for the most distinguished work in the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition.[75] The Diamond pieces were created between 1994 and 2005, made of shiny stainless steel seven-feet wide.[76]

Created in an edition of five versions, his later work Tulips (1995–2004) consists of a bouquet of multicolor balloon flowers blown up to gargantuan proportions (more than 2 m (6.6 ft) tall and 5 m (16 ft) across).[77] Koons started to work on Balloon Flower in 1995.[78]

Koons was pushing to finish the series in time for a 1996 exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, but the show was ultimately canceled because of production delays and cost overruns.[79] When "Celebration" funding ran out, the staff was laid off, a crew of two: Gary McCraw, Koons's studio manager, who had been with him since 1990, and Justine Wheeler, an artist from South Africa, who had arrived in 1995 and eventually took charge of the sculpture operation. The artist convinced his primary collectors Dakis Joannou, Peter Brant, and Eli Broad, along with dealers Jeffrey Deitch, Anthony d'Offay, and Max Hetzler, to invest heavily in the costly fabrication of the Celebration series at Southern California-based Carlson & Company (including his Balloon Dog and Moon series),[79][80] and later, at Arnold, a Frankfurt-based company. The dealers funded the project in part by selling works to collectors before they were fabricated.[81]

In 2006, Koons presented Hanging Heart, a 9-foot-tall highly polished, steel heart, one of a series of five differently colored examples, part of his Celebration series.[82] Large sculptures from that series were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2008. Later additions to the series include Balloon Swan (2004–2011), an 11.5-foot (3.5-meter), stainless-steel bird,[83] Balloon Rabbit (2005–2010), and Balloon Monkey, all for which children's party favors are reconceived as mesmerizing monumental forms.[84]

The series also includes, in addition to sculptures, sixteen[85] oil paintings.[86]

Easyfun and Easyfun-Ethereal

[edit]

Commissioned by the Deutsche Guggenheim in 1999, Koons created the first seven paintings of the new series, Easyfun, comprising paintings and wall-mounted sculptures.[87] In 2001, Koons undertook a series of paintings, Easyfun-Ethereal, using a collage approach that combined bikinis, food, and landscapes painted under his supervision by assistants.[88] The series eventually expanded to twenty-four paintings.[87]

Split-Rocker

[edit]In 2000, Koons designed Split-Rocker, his second floral sculpture made of stainless steel, soil, geotextile fabric, and an internal irrigation system, which was first shown at the Palais des Papes in Avignon, France. Like Puppy, it is covered with around 27,000 live flowers,[89] including petunias, begonias, impatiens, geraniums and marigolds.[90] Weighing 150 tons and soaring over 37 feet high, Split-Rocker is composed of two halves: one based on a toy pony belonging to one of Koons's sons, the other based on a toy dinosaur. Together, they form the head of a giant child's rocker. Koons produced two editions of the sculpture. As of 2014, he owns one of them;[90] the other is displayed at Glenstone in Maryland.[89] At Glenstone, Split-Rocker is in bloom from mid-May to mid-October, and requires daily caretaking during that period.[91] In summer 2014 Split-Rocker was installed at Rockefeller Plaza in New York City for several months in coincidence with the opening of Koons's retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Popeye and Hulk Elvis series

[edit]Paintings and sculptures from the Popeye series, which Koons began in 2002, feature the cartoon figures of Popeye and Olive Oyl.[92] One such item is a stainless steel reproduction of a mass-market PVC Popeye figurine.[93] The artist will also make use of inflatable animals again, this time in combination with ladders, trashcans and fences. To create these sculptures, the toys get a layer of coating after finding the right shape. Then a hard copy is made and sent to the foundry to be cast in aluminium. Back in the studio the sculptures are painted in order to achieve the shiny look of the original inflatables.[94] For these surrealist installations, Acrobat in particular, Koons got inspiration from the Chicago Imagist H.C. Westermann.[95] The Popeye sculpture was purchased by billionaire Steve Wynn for $28 million and it is displayed outside the casino entrance at Wynn's Encore Boston Harbor hotel and casino property.[96]

Hulk Elvis is a work series by Koons created between 2004 and 2014.[97] The works range from precision-machined bronze sculptures—inspired by an inflatable of the popular comic book hero and extruded in three dimensions—to large-scale oil paintings.[98] The work series' title combines the popular comic book hero Hulk with the pop icon Elvis. The triple image of the Hulk figure recalls Andy Warhol's silk-screen printing Triple Elvis (1963), regarding both the multiplication and the posture of the Hulk figure.[99]

According to the artist, the Hulk Elvis series with its strong, heroic image of the Hulk represents "a very high-testosterone body of work".[100] Koons also perceives the series as "a bridge between East and West", since a parallel might be drawn between the comic book hero Hulk and Asian guardian Gods.[101]

The three-dimensional works Hulk (Friends) and Hulks (Bell) (both 2004–2012) feature apparently inflatable Incredible Hulks that weigh almost a ton each and are made of bronze and wood.[102] The sculpture Hulk (Organ) (2004–2014) includes a fully functional musical instrument whose potential deep sounds match the figure's powerful and masculine appearance.[103]

The series' paintings are collages made of several photoshop layers. The images range from abstract landscapes to elements of American iconography (trains, horses, carriages) and comprise characters such as the Hulk or an inflatable plastic monkey.[100] The landscape paintings often have explicit or implicit sexual content. For example, a recurrent crude line drawing of a vulva refers to Courbet's L'Origine du monde (1866).[104]

The Hulk Elvis series has been exhibited at a number of international art venues such as the Gagosian Gallery in London (2007), the Gagosian Gallery in Hong Kong, China (2014) and the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, Austria (2015).[105]

Antiquity series

[edit]In 2008, Jeff Koons started working on his Antiquity series, delving into themes of the portrayal of eros, fertility, and feminine beauty across the history of art.[106][107] At the center of each scene in the Antiquity paintings (2009–2013) is a famous ancient or classical sculpture, meticulously rendered in oil paint and scaled to the same size as the sculptures. The equally detailed backdrops include an Arcadian vision.[84] Koons makes use of contemporary technology, including CT scans and digital imaging, to produce the metal sculptures. He reinterprets historical figures through the creation of balloon-like sculptures, such as the Metallic Venus, and by integrating representative figures and characters from comic books.[106][108]

Referring to the ancient Roman marble statue Callipygian Venus, Metallic Venus (2010–2012) was made of high chromium stainless steel with transparent color coating and live flowering plants.[102]

In Ballerinas (2010–2014), Koons depicts figurines of dancers, derived from decorative porcelain works designed by Ukrainian artist Oksana Zhnikrup, at the imposing scale of classical sculpture.[109][110][111][112]

Gazing Ball series

[edit]In this series presented at Gagosian Gallery in 2015, Koons has taken 35 masterpieces, including Manet's Déjeuner sur l'Herbe, Géricault's Raft of the Medusa and Rembrandt's Self-Portrait Wearing a Hat, had them repainted in oil on canvas, and added a little shelf, painted as if it had sprouted directly from the image. Each work includes a blue glass gazing ball that sits on a painted aluminum shelf attached to the front of the painting. Both viewer and painting are reflected in the gazing ball.[113][114]

Gazing Ball takes its name from the mirrored spherical ornaments frequently found on lawns, gardens, and patios around Koons's childhood home in Pennsylvania.[115] After creating Gazing Ball paintings, Koons also made several white sculptures from the Greco-Roman era along with everyday utilitarian objects encountered in today's suburban and rural landscape, such as mailboxes and a birdbath.

Apollo series

[edit]In June 2022, Dakis Jouannou commissioned Koons to create an artwork for his space at DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, on the Greek island of Hydra. Koons created the series Apollo, including a sculpture titled Apollo Wind Spinner (2020–2022), a 9.1 meter (30-foot) wide reflective wind spinner above the Slaughterhouse art space. The walls within the Slaughterhouse have been transformed by using as the base the ancient frescoes from Boscoreale, near Pompeii. The exhibition includes several other new works including a pair of bronze Nike sneakers, Gazing Ball Tripod (2020–2022), and Plato's Solid Forms Wind Spinners (2020–2022).[116]

Recent work

[edit]For the 2007–2008 season in the Vienna State Opera, Koons designed the large-scale picture (176 sqm) Geisha as part of the exhibition series "Safety Curtain", conceived by museum in progress.[117] Koons worked with American pop performer Lady Gaga on her 2013 studio album Artpop, including the creation of its cover artwork featuring a sculpture he made of Lady Gaga.[118] In September 2014, the bi-annual arts and culture publication GARAGE Magazine published Koons's first ever digital artwork for the front of its print edition. The piece, titled Lady Bug, is an augmented reality sculpture that can only be viewed on mobile devices through a GARAGE Magazine app, which allows viewers to explore the piece from a variety of angles as if standing on top of it.[119]

In 2012, Koons bought Advanced Stone Technologies, an offshoot of the non-profit Johnson Atelier Technical Institute of Sculpture's stone division. He moved the high-tech stone workshop from New Jersey to a larger, 60,000 sq ft (5,600 m2) space near Morrisville, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The facility exists solely to fabricate Koons's works made of stone.[120]

In 2013 Koons created the sculpture Gazing Ball (Farnese Hercules), which was inspired by the Farnese Hercules.[121] The sculpture is made from white plaster and can be interpreted as perpetuating colorism in how we view the ancient world.[121]

Other projects

[edit]In 1999, Koons commissioned a song about himself on Momus's album Stars Forever.[122]

A drawing similar to his Tulip Balloons was placed on the front page of the Internet search engine Google. The drawing greeted all who visited Google's main page on April 30, 2008, and May 1, 2008.[123][124]

In 2006 Koons appeared on Artstar, an unscripted television series set in the New York art world. He had a minor role in the 2008 film Milk playing state assemblyman Art Agnos.[125]

In September 2012, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo gave Koons the task of helping to review the designs for a new Tappan Zee Bridge.[126]

In 2019, Koons unveiled Bouquet of Tulips, an 11-meter high commemorative sculpture in Paris modelled on the Statue of Liberty, honoring the victims of the November 2015 attacks.[127][128]

In February 2024, a SpaceX rocket carrying 125 of Koon's stainless steel miniature moon sculptures departed from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The sculptures, named after historical figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and Billie Holiday, were part of a larger project involving a lunar lander designed by Intuitive Machines. The lander, which also carried NASA equipment, reached the Moon on February 22.[129] Koons, inspired by President Kennedy's vision of space exploration, saw this project as a way to inspire society. This endeavor, which included plans for larger sculptures on Earth and corresponding NFTs, aimed to be the first authorized artwork on the moon, protected under the Artemis Accords.[130]

Curating

[edit]Koons acted as curator of an Ed Paschke exhibition at Gagosian Gallery, New York, in 2009.[131] He also curated an exhibition in 2010 of works from the private collection of Greek billionaire Dakis Joannou at the New Museum in New York City. The exhibition, Skin Fruit: Selections from the Dakis Joannou Collection, generated debate concerning cronyism within the art world as Koons is heavily collected by Joannou and had previously designed the exterior of Joannou's yacht Guilty.[132][133]

BMW Art Car

[edit]

Koons was the artist named to design the seventeenth in the series of BMW "Art Cars". His artwork was applied to a race-spec E92 BMW M3, and revealed to the public at The Pompidou Centre in Paris on June 2, 2010.[134] Backed by BMW Motorsport, the car then competed at the 2010 24 Hours of Le Mans in France.[135]

Collaborations

[edit]In 1989, Koons and fellow artist Martin Kippenberger worked together on an issue of the art journal Parkett; the following year, Koons designed an exhibition poster for Kippenberger.[136]

In 2013, Koons collaborated with American singer-songwriter and performance artist Lady Gaga for her third studio album, ARTPOP.[137] The album cover depicts a nude sculpture of Gaga made by Koons behind a blue ball sculpture, and pieces of other art works in the background such as Birth of Venus painted by Sandro Botticelli, which inspired Gaga's image through the new era, including in her music video for "Applause" and the performance of the song at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards.[138] The image of the cover was revealed piece-by-piece in a social marketing campaign where her fans had to tweet the Twitter hashtag "#iHeartARTPOP" to unlock it.[139] The song "Applause" itself includes the lyrics "One second I'm a Koons, then suddenly the Koons is me."

In April 2017, Koons collaborated with the French luxury fashion house Louis Vuitton for the "Masters Collection" and designed a series of handbags and backpacks featuring the reproductions of his favorite masterpieces by the Old Masters, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, Vincent van Gogh, Peter Paul Rubens and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Later that year he presented another handful of bags and accessories featuring the reproductions of works by Claude Monet, J. M. W. Turner, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin and François Boucher.[140] The prices range from $585 for a key chain to $4,000 for the large carryall.[141] he also collaborated with singer Cupcakke multiple times in 2019.

Wine

[edit]Koons has also produced some fine wine-related commissions. In December 2012, Chateau Mouton Rothschild announced that Koons was the artist for their 2010 vintage label – a tradition that was started in 1946. Other artists to design labels include Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró, amongst others.[142] In August 2013, Dom Pérignon released their 2004 vintage, with a special edition done by Koons, as well as a made-to-order case called the 'Balloon Venus'. This has a recommended retail price of €15,000.[citation needed]

Charity

[edit]From February 15 to March 6, 2008, Koons donated a private tour of his studio to the Hereditary Disease Foundation for auction on Charitybuzz.[citation needed] From his limited-edition 2010 Tulip designs for Kiehl's Crème de Corps, a portion of the proceeds went to the Koons Family Institute, an initiative of the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children.[21] Since his relationship with the International Centre began, Koons has given over US$4.3 million to the Institute that bears his family's name.[143]

Exhibitions

[edit]Since a 1980 window installation at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, Koons's work has been widely exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions. In 1986, he appeared in a group show with Peter Halley, Ashley Bickerton, Ross Minoru Lang and Meyer Vaisman at Sonnabend Gallery in New York. In 1997, the parisian Galerie Jerome de Noirmont organized his first solo show in Europe. His Made in Heaven series was first shown at the Venice Biennale in 1990.[57]

As a young artist, Koons was included in many exhibitions curated by Richard Milazzo including The New Capital at White Columns in 1984, Paravision at Postmasters Gallery in 1985, Cult and Decorum at Tibor De Nagy Gallery in 1986, Time After Time at Diane Brown Gallery in 1986, Spiritual America at CEPA in 1986, and Art at the End of the Social at The Rooseum, Malmö, Sweden in 1988. These exhibitions would be alongside other notable artists such as Ross Bleckner, Joel Otterson, and Kevin Larmon.[144]

His museum solo shows include the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (1988), Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (1993), Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin (2000), Kunsthaus Bregenz (2001), the Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli (2003), and a retrospective survey at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo (2004), which traveled to the Helsinki City Art Museum (2005). In 2008, the Celebration series was shown at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, and on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[145]

Considered as his first retrospective in France, the 2008 exhibition of 17 Koons sculptures at the Château de Versailles also marked the first ambitious display of a contemporary American artist organized by the château. The New York Times reported that "several dozen people demonstrated outside the palace gates" in a protest arranged by a little-known, right-wing group dedicated to French artistic purity. It was also criticized that ninety percent of the US$2.8 million in financing for the exhibition came from private patrons, mainly François Pinault.[146]

The May 31 – September 21, 2008, Koons retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago,[8][147][148] which was widely publicized in the press, broke the museum's attendance record with 86,584 visitors.[149][150] The exhibition included numerous works from the MCA collection, along with recent paintings and sculptures by the artist. The retrospective exhibition reflects the MCA's commitment to Koons's work as it presented the artist's first American survey in 1988.[151] For the final exhibition in its Marcel Breuer building, the Whitney Museum is planning to present a Koons retrospective in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Centre Pompidou, Paris.[152]

In July 2009, Koons had his first major solo show in London, at the Serpentine Gallery. Entitled Jeff Koons: Popeye Series, the exhibit included cast aluminum models of children's pool toys and "dense, realist paintings of Popeye holding his can of spinach or smoking his pipe, a red lobster looming over his head".[153]

In May 2012, Koons had his first major solo show in Switzerland, at the Beyeler Museum in Basel, entitled Jeff Koons. Shown are works from three series: The New,Banality and Celebration as well as the flowered sculpture Split-Rocker.[154]

Also in 2012, Jeff Koons. The Painter at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt focussed primarily on the artist's development as a painter, while in the show Jeff Koons. The Sculptor at the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt, the sculptures by Jeff Koons entered enter into dialogues with the historical building and a sculpture collection spanning five millennia.[155] Together, both shows form the largest showing of Koons's work to date.[156][157]

The artist enjoyed a 2014 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Scott Indrisek, writing for ARTINFO.com, described it as "brash, fairly entertaining, and as digestible as a pack of M&Ms".[158]

In 2019 an exhibition called Jeff Koons at the Ashmolean was held at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, United Kingdom.[159]

Recognition

[edit]Koons received the BZ Cultural Award from a local Berlin newspaper in 2000 and the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture in 2001. He was named a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 2002 and then promoted to Officier in 2007.[160] He received an honoroary doctorate from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2008.[161] He was given the 2008 Wollaston Award from the Royal Academy of Arts in London.[57] In 2013 he received the U.S. State Department's Medal of Arts.[162] In 2014, Koons received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Wayne Thiebaud during the International Achievement Summit in San Francisco.[163][164][165] In 2017 he accepted the annual Honorary Membership Award for Outstanding Contribution to Visual Culture from the Edgar Wind Society, University of Oxford.[166] Made Honorary Professor of Sculpture of the Fine Arts Academy of Carrara, at the 250th anniversary celebration ceremony at the Academy of Fine Arts, Carrara, Italy [April 16, 2019][167]

Art market

[edit]Koons is widely collected in America and Europe, where some collectors acquire his work in depth. Eli Broad has 24 pieces, and Dakis Joannou owns some 38 works from all stages of the artist's career.[74]

Koons has been represented by dealers such as Mary Boone (1979–1980), Sonnabend Gallery (1986–2021),[168] Galerie Max Hetzler, Jérôme de Noirmont and Gagosian Gallery. The exclusive right to the primary sale of the "Celebration" series was long held by Gagosian Gallery, his dominant dealer for many years. Since 2021, Pace Gallery has been representing Koons exclusively worldwide.[169]

Many of Koons's works have been sold privately at auctions. His auction records have primarily been achieved from his sculptures (especially those from his Celebration series), whereas his paintings are less popular.[170] In 2001, one of his three Michael Jackson and Bubbles porcelain sculptures sold for US$5.6 million. On November 14, 2007, Hanging Heart (Magenta/Gold) from the collection of Adam Lindemann, one of five in different colors, sold at Sotheby's New York for US$23.6 million becoming, at the time, the most expensive piece by a living artist ever auctioned.[82] It was bought by the Gagosian Gallery in New York, which the previous day had purchased another Koons sculpture, Diamond (Blue), for US$11.8 million from Christie's London.[171] Gagosian appears to have bought both Celebration series works on behalf of Ukrainian steel oligarch Victor Pinchuk.[172] In July 2008, his 11-foot (3.3 meter) Balloon Flower (Magenta) (1995–2000) from the collection of Howard and Cindy Rachofsky also sold at Christie's London for an auction record of US$25.7 million. In total, Koons was the top-selling artist at auction with €81.3 million of sales in the year to June 2008.[173]

During the late 2000s recession, however, art prices plummeted and auction sales of high-value works by Koons dropped 50 percent in 2009.[173] A violet Hanging Heart sold for US$11 million in a private sale.[174] However prices for the artist's earlier Luxury and Degradation series appear to be holding up. The Economist reported that Thomas H. Lee, a private-equity investor, sold Jim Beam J.B. Turner Train (1986) in a package deal brokered by Giraud Pissarro Segalot for more than US$15 million.[175] In 2012, Tulips (1995–2004) brought a record auction price for Koons at Christie's, selling to a telephone bidder for US$33.6 million, well above its high US$25 million estimate.[176] At Christie's in 2015, the oil on canvas Triple Elvis (2009) set a world auction record for a painting by the artist, selling for $8,565,000, over $5 million more than the previous high.[177] Koons's stainless steel Rabbit (1986) sold for $91.1 million at auction in 2019, making it the most expensive work sold by a living artist at auction.[169]

In 2018, billionaire art collector Steven Tananbaum brought a lawsuit against Koons and Gagosian Gallery for failing to deliver three sculptures, Balloon Venus, Eros and Diana, for which he paid $13 million.[178] Soon after, Hollywood producer Joel Silver filed a similar lawsuit against Gagosion and Koons for failure to deliver an $8 million sculpture in 2014. Both lawsuits were settled in 2019 and 2020.[179]

Classification

[edit]Among curators and art collectors and others in the art world, Koons's work is labeled as Neo-pop or Post-Pop as part of a 1980s movement in reaction to the pared-down art of Minimalism and Conceptualism in the previous decade. Koons resists such comments: "A viewer might at first see irony in my work ... but I see none at all. Irony causes too much critical contemplation".[180] Koons rejects any hidden meaning in his artwork.[181]

He has caused controversy by the elevation of unashamed kitsch into the high-art arena, exploiting more throwaway subjects than, for example, Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans. His work Balloon Dog (1994–2000) is based on balloons twisted into shape to make a toy dog.

Theorist Samito Jalbuena wrote, "From the beginning of his controversial career, Koons overturned the traditional notion of art inside and out. Focusing on banal objects as models, he questioned standards of normative values in art, and, instead, embraced the vulnerabilities of aesthetic hierarchies and taste systems."[182]

Evaluation and influence

[edit]Koons has received polarized reactions to his work. Critic Amy Dempsey described his Balloon Dog as "an awesome presence ... a massive durable monument".[183] Jerry Saltz at artnet.com has commented on being "wowed by the technical virtuosity and eye-popping visual blast" of Koons's art.[184] Koons was among the names in Blake Gopnik's 2011 list "The 10 Most Important Artists of Today", with Gopnik arguing, "Even after 30 years, Koons's mashups of high and low—a dog knotted from balloons, then enlarged into a public monument; a life-size bust of Michael Jackson and his chimp in gold-and-white porcelain—still feel significant."[185]

Mark Stevens of The New Republic dismissed him as a "decadent artist [who] lacks the imaginative will to do more than trivialize and italicize his themes and the tradition in which he works... He is another of those who serve the tacky rich".[186] Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times saw "one last, pathetic gasp of the sort of self-promoting hype and sensationalism that characterized the worst of the 1980s" and called Koons's work "artificial", "cheap", and "unabashedly cynical".[187]

In an article comparing the contemporary art scene with show business, critic Robert Hughes wrote that Koons is

an extreme and self-satisfied manifestation of the sanctimony that attaches to big bucks. Koons really does think he's Michelangelo and is not shy to say so. The significant thing is that there are collectors, especially in America, who believe it. He has the slimy assurance, the gross patter about transcendence through art, of a blow-dried Baptist selling swamp acres in Florida. And the result is that you can't imagine America's singularly depraved culture without him.[188]

Hughes placed Koons's work just above that of Seward Johnson and was quoted in a New York Times article as having stated that comparing their careers was "like debating the merits of dog excrement versus cat excrement".[189]

He has influenced younger artists such as Damien Hirst[20] (for example, in Hirst's Hymn, an 18 ft (5.5 m) version of a 14 in (0.36 m) anatomical toy), Jack Daws,[190] Matthieu Laurette[191] and Mona Hatoum.[citation needed] In turn, his extreme enlargement of mundane objects owes a debt to Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. Much of his work also was influenced by artists working in Chicago during his study at the Art Institute, including Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke and H. C. Westermann.[192]

In 2005, he was elected as a Fellow to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[193]

Copyright infringement litigation

[edit]Koons has been sued several times for copyright infringement over his use of pre-existing images, the original works of others, in his work. In Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld a judgment against him for his use of a photograph of puppies as the basis for a sculpture, String of Puppies.[194]

Koons also lost lawsuits in United Features Syndicate, Inc. v. Koons, 817 F. Supp. 370 (S.D.N.Y. 1993), and Campbell v. Koons, No. 91 Civ. 6055, 1993 WL 97381 (S.D.N.Y. April 1, 1993).[citation needed]

He won one lawsuit, Blanch v. Koons, No. 03 Civ. 8026 (LLS), S.D.N.Y., November 1, 2005 (slip op.),[195] affirmed by the Second Circuit in October 2006, brought over his use of a photographic advertisement as source material for legs and feet in a painting, Niagara (2000). The court ruled that Koons had sufficiently transformed the original advertisement so as to qualify as a fair use of the original image.[196]

In 2015, Koons faced allegations he used photographer Mitchel Gray's 1986 photo for Gordon's Gin in one of his Luxury and Degradation paintings without permission or compensation.[197]

In 2018, a French court ruled that his 1988 work Fait d'Hiver, which depicts a pig standing over a woman who is lying on her back, had copied an advertisement for a clothing chain and found Koons and the Centre Pompidou guilty of infringing photographer Franck Davidovici's copyright.[198] This decision was upheld in 2021 on appeal. The result is that the work, owned by Foundazione Prada, cannot be displayed in France and the museum and artist cannot display photographic reproductions online (without a penalty of €600 per day). In addition, the museum and artist were ordered to jointly pay €190,000 and the book company €14,000.[199]

In 2019, a French court ruled that his work 1988 Naked, which depicts a little boy offering flowers to a little girl, both of whom are naked, had infringed on the copyright of a 1975 postcard photograph by French artist Jean-Francois Bauret.[198]

Koons has also accused others of copyright infringement, claiming that a bookstore in San Francisco infringed his copyright in Balloon Dogs by selling bookends in the shape of balloon dogs.[200] Koons dropped the lawsuit after the bookstore's lawyer filed a motion for declaratory relief stating, "As virtually any clown can attest, no one owns the idea of making a balloon dog, and the shape created by twisting a balloon into a dog-like form is part of the public domain".[201]

A Koons sculpture of a ballerina resembles the piece Ballerina Lenochka created by the Ukrainian artist Oksana Zhnykrup in 1974.[202]

In a 2021 complaint filed at the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, artist Michael Hayden who made a sculpture in 1988 of a serpent wrapped around a rock for Ilona Staller claimed that Koons unlawfully used the sculpture in his works.[203]

ICMEC's Koons Family Institute on International Law and Policy

[edit]Koons is a member of the board of directors of the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC), a global nonprofit organization that combats child sexual exploitation, child pornography, and child abduction.[204] In 2007, Koons, along with his wife Justine, founded the ICMEC Koons Family Institute on International Law and Policy.[205]

Following the end of his first marriage in 1994 to Hungarian-born Italian actress Ilona Staller, Staller left for Italy with their two-year-old son in violation of a US court order.[206][207] Koons spent five years pursuing his parental rights. The Italian Supreme Court ruled in favor of Staller. Koons subsequently established the Koons Family Institute.[208] In 2008, Staller filed suit against Koons for failure to pay child support.[209]

Personal life

[edit]While a student at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Koons fathered a daughter, Shannon Rodgers. The couple put the child up for adoption. Rodgers reconnected with Koons in 1995.[210] Koons has said that the adoption "helped make me want to have more visibility so that my daughter could find me. I always hoped that we could reconnect."[210]

In 1991, he married Hungarian-born naturalized-Italian pornography star Ilona Staller (Cicciolina) who at the time was a member of the Italian Parliament (1987–1992). Koons collaborated with Staller for the "Made in Heaven" paintings and sculptures in various media, with the hopes of making a film. While maintaining a home in Manhattan, Koons and Staller lived in Munich.[211] In 1992, they had a son, Ludwig. The marriage ended soon afterward amid allegations that Koons had subjected Staller to physical and emotional abuse.[212]

Koons later married Justine Wheeler, an artist and former employee who began working in Koons's studio in 1995. As of June 2009[update], the couple have four children together.[213] In January 2009, the family were living in an Upper East Side townhouse.[214]

Koons donated $50,000 to Correct the Record, a Super PAC which supported Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign in June 2016.[215]

Film and video

[edit]- Jeff Koons: the Banality Work by Jeff Koons, Paul Tschinkel, Sarah Berry. Videorecording produced by Inner Tube Video and Sonnabend Gallery (New York, NY), 1990.

- His Balloon Dog (Red) sculpture was one of the artworks brought to life in the 2009 film Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian.

- The Price of Everything, directed by Nathaniel Kahn and produced by Jennifer Blei Stockman, Debi Wisch and Carla Solomon, and distributed by HBO Documentary Films, 2018.

- He contributed to the Cupcakke song "Squidward's Nose" which gained popularity on social media app TikTok.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Famous birthdays for Jan. 21: Geena Davis, Luke Grimes". UPI. January 21, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (November 12, 2013). "At $142.4 Million, Triptych Is the Most Expensive Artwork Ever Sold at an Auction". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koons' $91M 'Rabbit' sculpture sets new auction record". CNN. May 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Tully, Kathryn (June 26, 2014). "The Most Expensive Art Ever Sold At Auction: Christie's Record-Breaking Sale". Forbes. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ^ Galenson, David (October 2006). "You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster". Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research: 25. doi:10.3386/w12599. S2CID 193985522,

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) citing Koons, The Jeff Koons Handbook. - ^ "Jeff Koons brings pop art revolution to Versailles". YouTube. September 16, 2008. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Wood, Gaby (June 3, 2007). "The wizard of odd". The Observer. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Schjeldahl, Peter (June 2, 2008). "Funhouse: A Jeff Koons retrospective". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Angelika Muthesius: Jeff Koons. Cologne 1992. p. 12.

- ^ Gayford, Martin. "Selling Candy to the Masses: Koons talks about sex, pleasure and future works" Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Apollo, March 1, 2008. Retrieved on June 9, 2009.

- ^ Rawsthorn, Alice (February 7, 2019). "Mr Big Stuff: Jeff Koons At Work And Play". Esquire. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Jeff Koons". The Huffington Post. July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Jeff Koons at SAIC | School of the Art Institute of Chicago". www.saic.edu. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Randy (February 24, 2010). "The Koons Collection". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Metz, Nina (May 25, 2008). "Jeff Koons' Manhattan home is mixture of beautiful and mundane". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Sischy, Ingrid (October 3, 2007). "Koons, High and Low". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons. New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker. 1981 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Koons, Jeff; Holzwarth, Hans Werner; Siegel, Katy, eds. (2007). Jeff Koons. Hong Kong Köln London Los Angeles, Calif. Madrid Paris Tokyo: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-4944-6.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Tulips (1995–2004) Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Guggenheim Bilbao.

- ^ a b c Akbar, Arifa (November 16, 2007). "Koons Most Expensive Living Artist at Auction". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Davies, Lucy (June 18, 2012). "Is Jeff Koons having a laugh?". The Telegraph. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Schneider, Tim (January 17, 2019). "Who Needs Assistants When You Have Robots? Jeff Koons Lays Off Dozens in a Move Toward a Decentralized, Automated Studio Practice". Artnet. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ Art21 (March 7, 2024). Jeff Koons in "Fantasy" - Season 5 - "Art in the Twenty-First Century" | Art21. Retrieved May 16, 2024 – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Powers, John (August 17, 2012). "I Was Jeff Koons's Studio Serf". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons: highlights of 25 years. New York, C & M Arts. 2004. ISBN 9780974424910.

- ^ Hans Werner Holzwarth: Jeff Koons. Cologne 2009. pp. 70–72.

- ^ Artist Rooms Jeff Koons, March 19 − July 3, 2011 Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

- ^ Jeff Koons, New Hoover Convertibles, New Shelton Wet/Drys 5-Gallon, Double Decker (1986) Christie's Post War And Contemporary Art Evening Sale, May 13, 2008.

- ^ "The New: Encased Works". Jeff Koons. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Three Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (Two Dr J Silver Series, Spalding NBA Tip-Off) (1985) Tate Collection.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Encased – Five Rows (6 Spalding Scottie Pippen Basketballs, 6 Spalding Shaq Attaq Basketballs, 6 Wilson Supershot Basketballs, 6 Wilson Supershot Basketballs, 6 Franklin 6034 Soccerballs), 1983–1993[permanent dead link] Phillips de Pury & Company, London.

- ^ Koons, Jeff; Bonami, Francesco; Warren, Lynne (2008). Jeff Koons. Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago, Ill.). Chicago : New Haven: Museum of Contemporary Art ; In association with Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14194-8. OCLC 260294279.

- ^ Freeman, Nate (April 19, 2019). "Why Jeff Koons's "Rabbit" Could Sell for up to $70 Million". Artsy. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (November 23, 2007). "A Bunny Balloon Sheds Its Steel Skin". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Milroy, Sarah (October 2, 2009). "Jeff Koons explains his Nuit Blanche Rabbit Balloon". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Hans Werner Holzworth: Jeff Koons. Cologne 2009. pp. 219–222.

- ^ "Exhibitions". Daniel Weinberg Gallery. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Jim Beam-Box Car (1986) Christie's Post War And Contemporary Art Evening Sale, May 13, 2008.

- ^ Joan Gibbons: Art and Advertising. London 2005. p. 150.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Jim Beam – J.B. Turner Engine (1986) Christie's Post War and Contemporary Evening Sale, May 13, 2009.

- ^ "Jeff Koons, Jim Beam – Baggage Car". www.christies.com. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ "Jeff Koons Artwork: Jim Beam – Baggage Car". Jeff Koons. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ Andrew Renton, "Jeff Koons and the Art of Deal: Marketing (as) Sculpture", Performance Magazine 61/ 1990. p. 25.

- ^ Hans Werner Holzwarth: Jeff Koons. Cologne 2009. pp. 242–243.

- ^ Angelika Muthesius: Jeff Koons. Cologne 1992. p. 23.

- ^ "Jackson sculpture breaks record". BBC News. May 16, 2001. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Michael Jackson and Bubbles". Astrup Fearnley Museet. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Gauvin Alexander Bailey, The Spiritual Rococo: Decor and Divinity from the Salons of Paris to the Missions of Patagonia (Farnham, 2014): 310–11.

- ^ Brenson, Michael (December 18, 1988). "Gallery View: Greed Plus Glitz, with a Dollop of Innocence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons". Astrup Fearnley Museet. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008.

- ^ Jeff Koons Archived October 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Signature Plate (Parkett 19) (1988) Christie's Prints & Multiples, February 7–8, 2008, New York.

- ^ Hans Werner Holzwarth: Jeff Koons. Cologne 2009. p. 306.

- ^ Anthony, Andrew (October 15, 2011). "The Koons show". The Observer. London. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Roberta (October 13, 2010). "That Was No Lady, That Was My Wife". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "On the 20th anniversary of Jeff Koons' "Made in Heaven" series, major paintings to go on view in New York". Luxembourg + Co. August 24, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Jeff Koons[permanent dead link], Guggenheim Collection.

- ^ Wolff, Rachel (February 6, 2009). "A Towhouse Full of High-Art Smut". New York Magazine. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Robert C. (January 2011). "Tumescent Follies, Inflated Money, and Kitschy Sex". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (July 5, 1992). "ART VIEW; How Much Is That Doggy in the Courtyard?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Jeff Koons: Puppy, June 6 – September 5, 2000 Archived April 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Public Art Fund.

- ^ Angelika Muthesius: Jeff Koons. Cologne 1992. p. 32.

- ^ Hans Werner Holzwarth: Jeff Koons. Cologne 2009. pp. 375–376.

- ^ Angelika Muthesius: Jeff Koons. Cologne 1992. p. 33.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales – Archive – 1995 Jeff Koons". archive.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales – Archive – 1995 Jeff Koons". archive.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Gil, Lorena (October 14, 2007). "En el corazón de Puppy". El Correo (in European Spanish). Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Robinson, Walter (October 14, 1997). "Terror attack at Gugg Bilbao". Artnet. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Izarra, J.; Herrero, R. (October 14, 1997). "Atentado frustrado contra el Guggenheim". El Mundo. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ^ Muñoz, Juan Miguel (October 20, 1997). "Un sindicato policial dice que personas con antecedentes trabajaban en el Guggenheim". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Jason Edward. "Peter Brant and Stephanie Seymour put their contemporary art collection on show", The Art Newspaper, April 8, 2009.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Puppy (vase) (1998), Sale 3019, The Jan & Monique des Bouvrie Collection, Amsterdam, September 6, 2011.

- ^ "François Pinault foundation – Palazzo Grassi Venice | Palazzo Grassi". February 19, 2014. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "Inflatable investments". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Wollaston Award Announcement Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sandler, Linda (September 25, 2013). "Jeff Koons's 'Blue Diamond' for Sale at Christie's New York". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Tulips (1995–2004) Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Guggenheim Bilbao.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Balloon Flower (Magenta) Christie's Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Sale, June 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Finkel, Jori (April 27, 2008). "At the Ready When Artists Think Big". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Young, Paul (January 9, 2008). "Those Fabulous Fabricators and Their Finish Fetish". LA Weekly. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Kelly Devine (May 1, 2005). "The Selling of Jeff Koons". ARTnews.com. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koon's Hanging Heart Sets Record At Auction" Archived October 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Culturekiosque, November 15, 2007.

- ^ "Sexy contemporary antiquities". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koons: New Paintings and Sculpture, 555 West 24th Street, New York, May 9 – June 29, 2013". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons: Cracked Egg (Blue), Davies Street, London, October 2 – December 22, 2006". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons's giant Easter Egg with bow in Boijmans, 22 February 2012 – 2015 Archived May 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koons: Easyfun-Ethereal, 555 West 24th Street, New York, March 10 – April 21, 2018". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons, May 13 – September 29, 2012 Archived May 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Fondation Beyeler, Basel.

- ^ a b Spivack, Miranda S. (June 24, 2013). "Rales family unveils plans for major new Glenstone museum in Potomac". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Vogel, Carol (May 29, 2014). "A Jeff Koons Sculpture Is Coming to 30 Rock". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Honker, Carmen (June 15, 2022). "Glenstone's Jeff Koons Sculpture Has 24,000 Plants and One Seriously Dedicated Caretaker". Washingtonian. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Jeff Koons: Popeye Series, 2 July – 13 September 2009 Serpentine Gallery, London.

- ^ "Did Jeff Koons Just Make $28 Million By Plagiarizing A Dark Horse Popeye Toy?". May 15, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ Francesco Bonami: Jeff Koons. Chicago 2008. p. 99.

- ^ Francesco Bonami: Jeff Koons. Chicago 2008. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Miller, Joshua (May 31, 2019). "An early look at the Encore casino's millions of dollars' worth of art". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "Jeff Koons Artwork". Jeff Koons. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Jeff Koons: Hulk Elvis, Hong Kong, November 6 – December 20, 2014". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Francesco Bonami: Jeff Koons. Chicago 2008. p. 109. ISBN 978-0300141948

- ^ a b Sooke, Alastair (June 9, 2007). "Face to face with the incredible hulk of American contemporary art". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ McHugh, Fionnuala (November 20, 2014). "Jeff Koons brings artworks to Hong Kong". www.scmp.com. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koons Fashions Venus's Buttocks in Shiny Steel". Bloomberg.com. June 24, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons. Hulk Elvis". Wall Street International. October 31, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Koons, Jeff; Rothkopf, Scott (2009). Jeff Koons. Hulk Elvis. Exhibition Catalogue (1 June – 27 July 2007, Gagosian Gallery in London). New York: Rizzoli. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8478-3359-7.

- ^ "Current and Upcoming Solo Exhibitions". Jeff Koons. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Jeff Koons: New Paintings and Sculpture, 555 West 24th Street, New York, May 9–June 29, 2013". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Antiquity - - Series - Two Palms". www.twopalms.us. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Koons, Jeff; Rothkopf, Scott; Whitney Museum of American Art; Centre Georges Pompidou; Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, eds. (2014). Jeff Koons: a retrospective. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. ISBN 978-0-300-19587-3.

- ^ "Jeff Koons, Beverly Hills, April 27 – August 18, 2017". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Надувна балерина Кунса у Нью-Йорку – це "законна копія"". nv.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ "US artist Jeff Koons, controversies and complaints". France 24. May 16, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Gatten, Emma (May 25, 2017). "Jeff Koons accused of copying Ukrainian artist's work". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ "Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Paintings, West 21st Street, New York, November 9 – December 23, 2015". Gagosian. April 12, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Needham, Alex (November 9, 2015). "Jeff Koons on his Gazing Ball Paintings: 'It's not about copying'". the Guardian. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball". David Zwirner. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "JEFF KOONS: APOLLO | DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art | Athens | Greece". deste.gr. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Eiserner Vorhang 2007/2008". museum in progress (in Austrian German). Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Backplane". LittleMonsters. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Sokol, Zach (September 2, 2014). "Jeff Koons Is Releasing His First Piece Of Digital Art". www.vice.com. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Rachel Corbett (March 3, 2015), Koons at cutting edge with giant stone mills Archived March 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ a b Hinds, Aimee (June 23, 2020). "Hercules in White: Classical Reception, Art and Myth". The Jugaad Project. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- ^ "AllMusic Review by Jason Ankeny". AllMusic. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Guest Doodle by Jeff Koons". Google.com. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ April 30 is Queen's Day in the Netherlands.

- ^ Delahoyde, Steve. "Jeff Koons Makes a Surprising Turn as an Actor in Milk" Archived December 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Media Bistro, December 8, 2008.

- ^ Kaplan, Thomas (September 19, 2012). "Seeking an Artist's Touch for the New Tappan Zee Bridge". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Gareth Harris (November 22, 2016), Jeff Koons unveils plans for a memorial to the victims of the Paris terror attacks The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "Jeff Koons Artwork: Bouquet of Tulips". Jeff Koons. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Marcia Dunn (February 23, 2024). "Private lander makes first US moon landing in more than 50 years". Associated Press. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Small, Zachary (February 15, 2024). "Jeff Koons Sculptures Hitch Ride on SpaceX Rocket to the Moon". The New York Times.

- ^ "Ed Paschke: Curated by Jeff Koons, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, March 18 – April 24, 2010". Gagosian. April 24, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Larocca, Amy (February 26, 2010). "61 Minutes With Dakis Joannou". New York Magazine. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Fontevecchia, Agustino. "Dakis Joannou's Mega Yacht 'Guilty' By Jeff Koons And Ivana Porfiri, An Act Of Calculated Irreverence". Forbes. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ "BMW Art Car by Jeff Koons to race at Le Mans 24 hour". AUSmotive.com. June 7, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Liberman, Jonny (February 2, 2010). "BMW picks Jeff Koons as artist for next Art Car". Autoblog. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Yablonsky, Linda (April 21, 2015). "A Christie's Auction Brings Together the Art, and History, of Jeff Koons and Martin Kippenberger". T Magazine. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Pasori, Cedar (July 12, 2013). "Lady Gaga Announces ARTPOP Collaborations With Jeff Koons, Marina Abramovic, Inez & Vinoodh, and Robert Wilson". Complex. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Popjustice (October 7, 2013). "Lady Gaga has unveiled the 'ARTPOP' artwork • Popjustice". Popjustice. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Lady Gaga [@ladygaga] (October 7, 2013). "Album cover can be unlocked in 30 min by trending #iHeartARTPOP ! I'll be in the bathroom throwing up #iHeartPanicAttack #WheresMyInhaler" (Tweet). Retrieved May 30, 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Louis Vuitton

- ^ Tai, Cordeila (April 11, 2017). "Louis Vuitton x Jeff Koons Is Here to Tantalize Art (and Handbag) Lovers". The Fashion Spot. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Shaw, Lucy (December 17, 2012). "Jeff Koons designs Mouton 2010 label". The Drinks Business. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Melanie Grayce West (May 24, 2012), Pooling Resources to Fight Child Abuse and Abduction Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Milazzo, Richard. "Peter Nadin". Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2014. Peter Nadin: An Odyssey of the Mark in Painting. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ "Jeff Koons on the Roof". www.metmuseum.org. 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (September 10, 2008). "At the Court of the Sun King, Some All-American Art". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Freudenheim, Tom L. (August 30, 2008). "A Tarnished Jeff Koons". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Hester, Jessica (June 3, 2008). "Kitsch master Koons unveils MCA retrospective". The Chicago Maroon. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Conrad, Marissa (December 2008). "The Innovator". Chicago Social. Chicago: 140.

- ^ "Jeff Koons". Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ "Jeff Koons at Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago". Artdaily. 2008. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (May 10, 2012). "Before Whitney's Move, a Koons Retrospective". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (July 2, 2009). "Koons and a Sailor Man in London". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Enrico (May 14, 2012). "Jeff Koons at Fondation Beyeler". Vernissage TV. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Koons. The Painter". Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (in German). August 6, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Thornton, Sarah (June 22, 2012). "Sarah Thornton on Jeff Koons at the Schirn Kunsthalle and Liebieghaus". Artforum International. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Koons, Jeff; Ulrich, Matthias; Brinkmann, Vinzenz; Pissarro, Joachim; Hollein, Max; Liebieghaus; Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (2012). Jeff Koons : the painter & the sculptor. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz. ISBN 978-3-7757-3371-7. OCLC 794364561.

- ^ Indrisek, Scott. "All Aboard The 'Great Koonsian Adventure'", June 26, 2014.

- ^ "CURRENT AND UPCOMING SOLO EXHIBITIONS". Jeff Koons. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ "Conceptual Artist Jeff Koons to Speak at UNLV Dec. 10". November 25, 2002. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Past Speakers and Honorary Degree Recipients". School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Smithsonian Magazine, December 2013, pg. 4.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "2014 Summit Photo: Internationally acclaimed artist and member of the Academy's Class of 2014, Jeff Koons, discusses his artwork". Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Wayne Thiebaud Biography and Interview Photo: Council member Wayne Thiebaud presents the American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award to contemporary art phenomenon Jeff Koons at the 2014 International Achievement Summit in San Francisco". Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "The Edgar Wind Society, University of Oxford". Archived from the original on November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Biography – Awards and Honors". Jeff Koons. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (December 6, 2012). "'Inventing Abstraction' at MoMA, Collaboration With WQXR". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Pogrebin, Robin (April 26, 2021). "Jeff Koons Moves to Pace Gallery". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Georgina Adam (June 15, 2012), Things that go pop: Jeff Koons's seesaw market The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Segal, David (November 14, 2007). "Reflective Surface". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Thornton, Sarah. "Recipe for a Record Price", The Art Newspaper, No. 191, May 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Reyburn, Scott (December 29, 2009). "Koons, Hirst Prices Drop 50%; May Take Next Decade to Recover". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (April 25, 2009). "More Artworks Sell in Private in Slowdown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Crossing to safety". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (November 15, 2012). "Relentless Bidding, and Record Prices, for Contemporary Art at Christie's Auction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Jeff Koons, Triple Elvis (2009) Christie's Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale, May 13, 2015, New York.

- ^ Sutton, Benjamin (April 19, 2018). "Collector Who Paid $13M Sues Jeff Koons and Gagosian". Hyperallergic. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Dafoe, Taylor (February 3, 2020). "Billionaire Steven Tananbaum Settles with Gagosian, Ending a Bitter Lawsuit Over Three Long-Delayed Jeff Koons Sculptures". Artnet. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Galenson, David W. (2009). Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art, p. 176. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 052111232X, 9780521112321.

- ^ Arthur C. Danto: Unnatural Wonders. Essays from the Gap Between ARt and Life. New York 2005. 286–302.

- ^ Jalbuena, Samito (November 11, 2014). "Jeff Koons lands in Asia for first major show in Hong Kong". BusinessMirror. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Dempsey, Amy (ed.). Styles, Schools and Movements, Thames & Hudson, 2002.

- ^ Saltz, Jerry (December 16, 2003). "Breathing leassons". www.artnet.com. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Gopnik, Blake (June 5, 2011). "The 10 Most Important Artists of Today". Newsweek. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Stevens, Mark. "Adventures in the Skin Trade", The New Republic, January 20, 1992.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael. "Jeff Koons", The New York Times, November 29, 1991.

- ^ Hughes, Robert. "Showbiz and the Art World", The Guardian, 30 June 2004.

- ^ Wadler, Joyce (October 12, 2006). "After Calamity, a Critic's Soft Landing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Hackett, Regina (August 15, 2003). "Life's flaws inspire Jack Daws' wicked sense of play". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "New Hoover Celebrity IV". Jeffkoons.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Everything's Here: Jeff Koons and His Experience of Chicago". MCA Chicago. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ "Academy Elects 225th Class of Fellows and Foreign Honorary Members, Including Scholars, Scientists, Artists, Civic, Corporate and Philanthropic Leaders". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. April 26, 2005.

- ^ "String of Puppies". Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Client Alert – crash test". CLL. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 263 (2d Cir. 2006).

- ^ Chung, Andrew (December 15, 2015). "Artist Jeff Koons sued for copyright infringement over gin ad photo". Reuters. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "French court upholds plagiarism ruling against Jeff Koons". France 24. AFP. December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ Greenberger, Alex (February 24, 2021). "Jeff Koons, Centre Pompidou Lose Appeal on French Fashion Ad Plagiarism Suit". ARTnews. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (February 4, 2011). "Jeff Koons' balloon-dog claim ends with a whimper". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Allen, Emma (January 21, 2011). "6 Hilarious Zingers From the Balloon-Dog Freedom Suit Filed Against Jeff Koons". www.artinfo.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Jeff Koons accused of copying Ukrainian artist's work". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ Brittain, Blake (December 2, 2021). "Pop artist Jeff Koons sued over adult film set prop". Reuters. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "ICMEC Board Members". icmec.org. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015.

- ^ "The Koons Family Institute on International Law & Policy". ICMEC. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015.

- ^ Sischy, Ingrid (June 16, 2014). "Has Jeff Koons Become a Pillar of the Art Establishment?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Tammy Duffy (July 11, 2014). "Jeff Koons: Retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art NYC". The Trentonian.