Non liquet

In law, a non liquet (commonly known as "lacuna in the law") is any situation for which there is no applicable law. Non liquet translates into English from the Latin as "it is not clear".[1] According to Cicero, the term was applied during the Roman Republic to a verdict of "not proven" if the guilt or innocence of the accused was "not clear".[2] Strictly, a finding of non liquet could result in a decision that the matter will always remain non-justiciable, but a lacuna denotes within that concept a lacking and so that the matter should in future be governed by law.

Loopholes are a subset of lacunae.

A lacuna is any specific matter about which no law exists, but a body of public, judicial or academic opinion believes it should exist to address a particular issue (often described as "unregulated" or "wholly inadequately regulated" activities or areas). A loophole where properly defined, by contrast, denotes that a set of laws addressing a certain issue exists but can be circumvented (or is being exploited) because of a technical defect in the law.

Related legal interpretative rules

[edit]Related legal interpretative rules include the purposive rule and the mischief rule of some Commonwealth countries such as in the law of England and Wales as to decidedly-unclear legislation (Acts or Regulations).

In short, the wording will be interpreted if dictionaries and grammar allow to plug the gaps in the law as the state instrument (or ruling) intended.

Relationship to development of common law

[edit]All cases that establish a new rule or exception fill lacunae in the existing law.

If it is in a higher court in the jurisdiction, each of the decisions is thereafter considered to be a binding precedent. In England and Wales, if the decision is in or below the various divisions of the High Court, it is of persuasive precedent value.[3]

Wider scope of morality

[edit]

Moral principles and norms are broader than the intended reach of any system of laws (jurisdiction), which permits human autonomy and diversity of thinking or action:

“It would not be correct to say that every moral obligation involves a legal duty; but every legal duty is founded on a moral obligation.”[4]

If the one-to-one relationship is accepted, that defines a definitive master set from which the subset, all true legal lacunae (as opposed to semantic omissions), is contained.

International law forums

[edit]A non liquet applies to facts with no answer from the governing system of law. It is prominent in international law as global forums such as the International Court of Justice and United Nations ad hoc tribunals, which are reluctant to invent or to mould law heavily to redress a moral-legal lacuna. One last resort in substantively deciding disputes is to seek the system to embrace accepted (lowest common denominator) procedural or non-controversial law of civilized nations. An instance is the Case Concerning Barcelona Traction, Light, and Power Company, Ltd, which took the doctrine of estoppel into international law. Such out-of-constrained confines (ex aequo et bono) jurisdiction has been heavily limited or ruled out by most treaty contracting parties as to their substantive obligations. Rather than use the term non-justiciable, the forum may flag up that it would like the clarity to decide on such matters in future by stating it is non liquet. Luhmann criticises such indecision as opposed to the paradigm of law being a complete (and autonomous) system.[5]

English jurisprudence holds that municipal courts enforcing international law are not constrained to declare an area non liquet.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Black's Law Dictionary (8th ed. 2004)

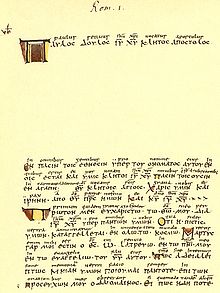

- ^ See Charton T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary, liqueo[1] and Cic. Clu. 18.76. Deinde homines sapientes et ex vetere illa disciplina iudiciorum, qui neque absolvere hominem nocentissimum possent, neque eum de quo esset orta suspicio pecunia oppugnatum, re illa incognita, primo condemnare vellent, non liquere dixerunt.[2]

- ^ Precedent in English Law, 4th Ed., Rupert Cross (Sir), p. 121

- ^ The Lord Chief Justice (Lord Coleridge) in giving the leading judgment in R v Instan (1893) 1 QB 450

- ^ Luhmann, Law as a Social System (Oxford, 2004), at p. 281.

- ^ Nourse LJ to that effect in [1988] 3 WLR 1118 : 80 ILR 135