LGBTQ movements

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBTQ people in society. Although there is not a primary or an overarching central organization that represents all LGBTQ people and their interests, numerous LGBTQ rights organizations are active worldwide. The first organization to promote LGBTQ rights was the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, founded in 1897 in Berlin.[4]

A commonly stated goal among these movements is equal rights for LGBTQ people, often focusing on specific goals such as ending the criminalization of homosexuality or enacting same-sex marriage. Others have focused on building LGBTQ communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society from biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. LGBTQ movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research.

Overview

[edit]

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

|

Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include (but are not limited to) challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm".[5] Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

As with other social movements, there is also conflict within and between LGBTQ movements, especially about strategies for change and debates over exactly who represents the constituency of these movements, and this also applies to changing education.[6] There is debate over the extent that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people, as well as others, share common interests and a need to work together. Leaders of the lesbian and gay movement of the 1970s, '80s and '90s often attempted to hide masculine lesbians, feminine gay men, transgender people, and bisexuals from the public eye, creating internal divisions within LGBTQ communities.[7] Roffee and Waling (2016) documented that LGBTQ people experience microaggressions, bullying and anti-social behaviors from other people within the LGBTQ community. This is due to misconceptions and conflicting views as to what entails "LGBT". For example, transgender people found that other members of the community were not understanding toward their own, individual, specific needs and would instead make ignorant assumptions, and this could cause health risks.[8] Additionally, bisexual people found that lesbian or gay people were not understanding or appreciative of bisexual sexuality. Evidently, even though most of these people would say that they stand for the same values as the majority of the community, there are still remaining inconsistencies even within the LGBTQ community.[9]

LGBTQ movements have often adopted a kind of identity politics that sees gay, bisexual, and transgender people as a fixed class of people; a minority group or groups, and this is very common among LGBTQ communities.[10] Those using this approach aspire to liberal political goals of freedom and equal opportunity, and aim to join the political mainstream on the same level as other groups in society.[11] In arguing that sexual orientation and gender identity are innate and cannot be consciously changed, attempts to change gay, lesbian, and bisexual people into heterosexuals ("conversion therapy") are generally opposed by the LGBTQ community. Such attempts are often based on religious beliefs that perceive gay, lesbian, and bisexual activity as immoral. Religion has, however, never been univocal opposed to either homosexuality, bisexuality or being transgender, usually treating sex between men and sex between women differently. As of today, numerous religious communities and many believers in various religions are generally accepting of LGBTQ rights.

However, others within LGBTQ movements have criticized identity politics as limited and flawed, elements of the queer movement have argued that the categories of gay and lesbian are restrictive, and attempted to deconstruct those categories, which are seen to "reinforce rather than challenge a cultural system that will always mark the non heterosexual as inferior."[12]

After the French Revolution the anticlerical feeling in Catholic countries coupled with the liberalizing effect of the Napoleonic Code made it possible to sweep away sodomy laws. However, in Protestant countries, where the church was less severe, there was no general reaction against statutes that were religious in origin. As a result, many of those countries retained their statutes on sodomy until late in the 20th century. However, some countries have still retained their statutes on sodomy. For example, in 2008 a case in India's High Court was judged using a 150-year-old reading that was punishing sodomy.[13]

History

[edit]Enlightenment era

[edit]In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, same-sex sexual behavior and cross-dressing were widely considered to be socially unacceptable, and were serious crimes under sodomy and sumptuary laws. There were, however, some exceptions. For example, in the 17th-century cross-dressing was common in plays, as evident in the content of many of William Shakespeare's plays and by the actors in actual performance (since female roles in Elizabethan theater were always performed by males, usually prepubescent boys).

Thomas Cannon wrote what may be the earliest published defense of homosexuality in English, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify'd (1749). Although only fragments of his work have survived, it was a humorous anthology of homosexual advocacy, written with an obvious enthusiasm for its subject.[14] It contains the argument: "Unnatural Desire is a Contradiction in Terms; downright Nonsense. Desire is an amatory Impulse of the inmost human Parts: Are not they, however, constructed, and consequently impelling Nature?"

Social reformer Jeremy Bentham wrote the first known argument for homosexual law reform in England around 1785, at a time when the legal penalty for buggery was death by hanging. His advocacy stemmed from his utilitarian philosophy, in which the morality of an action is determined by the net consequence of that action on human well-being. He argued that homosexuality was a victimless crime, and therefore not deserving of social approbation or criminal charges. He regarded popular negative attitudes against homosexuality as an irrational prejudice, fanned and perpetuated by religious teachings.[15] However, he did not publicize his views as he feared reprisal; his powerful essay was not published until 1978.

The emerging currents of secular humanist thought that had inspired Bentham also informed the French Revolution, and when the newly formed National Constituent Assembly began drafting the policies and laws of the new republic in 1792, groups of militant "sodomite-citizens" in Paris petitioned the Assemblée nationale, the governing body of the French Revolution, for freedom and recognition.[16] In 1791, France became the first nation to decriminalize homosexuality, probably thanks in part to Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, who was one of the authors of the Napoleonic Code. With the introduction of the Napoleonic Code in 1808, the Duchy of Warsaw also decriminalized homosexuality.[17]

In 1830, the new Penal Code of the Brazilian Empire did not repeat the title XIII of the fifth book of the "Ordenações Philipinas", which made sodomy a crime. In 1833, an anonymous English-language writer wrote a poetic defense of Captain Nicholas Nicholls, who had been sentenced to death in London for sodomy:

Whence spring these inclinations, rank and strong?

And harming no one, wherefore call them wrong?[16]

Three years later in Switzerland, Heinrich Hoessli published the first volume of Eros: Die Männerliebe der Griechen (English: "Eros: The Male Love of the Greeks"), another defense of same-sex love.[16]

Emergence of LGBT movement

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

In many ways, social attitudes to homosexuality became more hostile during the late Victorian era. In 1885, the Labouchere Amendment was included in the Criminal Law Amendment Act,[18] which criminalized 'any act of gross indecency with another male person'; a charge that was successfully invoked to convict playwright Oscar Wilde in 1895 with the most severe sentence possible under the Act.

The first person known to describe himself as a drag queen was William Dorsey Swann, born enslaved in Hancock, Maryland. Swann was the first American on record who pursued legal and political action to defend the LGBTQ community's right to assemble.[19] During the 1880s and 1890s, Swann organized a series of drag balls in Washington, D.C. Swann was arrested in police raids numerous times, including in the first documented case of arrests for female impersonation in the United States, on April 12, 1888.[20]

From the 1870s, social reformers began to defend homosexuality, but due to the controversial nature of their advocacy, kept their identities secret.[citation needed] The Uranian poets and prose writers, who sought to rehabilitate the love between men and boys and in doing so often appealed to Ancient Greece, formed a rather cohesive group with a well-expressed philosophy.[21] A secret British society called the Order of Chaeronea campaigned for the legalization of homosexuality. The society was founded in 1897 by George Cecil Ives, one of the earliest gay rights campaigners, who had been working for the end of oppression of homosexuals, what he called the "Cause".[22] Members included Oscar Wilde,[23] Charles Kains Jackson, Samuel Elsworth Cottam, Montague Summers, and John Gambril Nicholson. Ives met Wilde at the Authors' Club in London in 1892.[22] Wilde was taken by his boyish looks and persuaded him to shave off his mustache, and once kissed him passionately in the Travellers' Club.[citation needed] In 1893, Lord Alfred Douglas, with whom he had a brief affair, introduced Ives to several Oxford poets whom Ives also tried to recruit.

John Addington Symonds was a poet and an early advocate of male love. In 1873, he wrote A Problem in Greek Ethics, a work of what would later be called "gay history."[24] Although the Oxford English Dictionary credits the medical writer C.G. Chaddock for introducing "homosexual" into the English language in 1892, Symonds had already used the word in A Problem in Greek Ethics.[25]

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as Eudiades, which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems".[26] While the taboos of Victorian England prevented Symonds from speaking openly about homosexuality, his works published for a general audience contained strong implications and some of the first direct references to male-male sexual love in English literature. By the end of his life, Symonds' homosexuality had become an open secret in Victorian literary and cultural circles. In particular, Symonds' memoirs, written over a four-year period, from 1889 to 1893, form one of the earliest known works of self-conscious homosexual autobiography in English. The recently decoded autobiographies of Anne Lister are an earlier example in English.

Another friend of Ives was the English socialist poet Edward Carpenter. Carpenter thought that homosexuality was an innate and natural human characteristic and that it should not be regarded as a sin or a criminal offense. In the 1890s, Carpenter began a concerted effort to campaign against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, possibly in response to the recent death of Symonds, whom he viewed as his campaigning inspiration. His 1908 book on the subject, The Intermediate Sex, would become a foundational text of the LGBT movements of the 20th century. Scottish anarchist John Henry Mackay also wrote in defense of same-sex love and androgyny.

English sexologist Havelock Ellis wrote the first objective scientific study of homosexuality in 1897, in which he treated it as a neutral sexual condition. Called Sexual Inversion it was first printed in German and then translated into English a year later. In the book, Ellis argued that same-sex relationships could not be characterized as a pathology or a crime and that its importance rose above the arbitrary restrictions imposed by society.[27] He also studied what he called 'inter-generational relationships' and that these also broke societal taboos on age difference in sexual relationships. The book was so controversial at the time that one bookseller was charged in court for holding copies of the work. It is claimed that Ellis coined the term 'homosexual', but in fact he disliked the word due to its conflation of Greek and Latin.

These early proponents of LGBT rights, such as Carpenter, were often aligned with a broader socio-political movement known as 'free love'; a critique of Victorian sexual morality and the traditional institutions of family and marriage that were seen to enslave women. Some advocates of free love in the early 20th century, including Russian anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman, also spoke in defense of same-sex love and challenged repressive legislation.

An early LGBT movement also began in Germany at the turn of the 20th century, centering on the doctor and writer Magnus Hirschfeld. In 1897 he formed the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee campaign publicly against the notorious law "Paragraph 175", which made sex between men illegal. Adolf Brand later broke away from the group, disagreeing with Hirschfeld's medical view of the "intermediate sex", seeing male-male sex as merely an aspect of manly virility and male social bonding. Brand was the first to use "outing" as a political strategy, claiming that German Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow engaged in homosexual activity.[28]

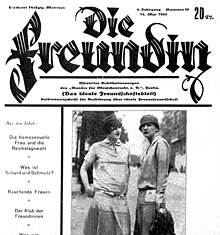

The 1901 book Sind es Frauen? Roman über das Dritte Geschlecht (English: Are These Women? Novel about the Third Sex) by Aimée Duc was as much a political treatise as a novel, criticizing pathological theories of homosexuality and gender inversion in women.[29] Anna Rüling, delivering a public speech in 1904 at the request of Hirschfeld, became the first female Uranian activist. Rüling, who also saw "men, women, and homosexuals" as three distinct genders, called for an alliance between the women's and sexual reform movements, but this speech is her only known contribution to the cause. Women only began to join the previously male-dominated sexual reform movement around 1910 when the German government tried to expand Paragraph 175 to outlaw sex between women. Heterosexual feminist leader Helene Stöcker became a prominent figure in the movement. Friedrich Radszuweit published LGBT literature and magazines in Berlin (e.g., Die Freundin).

Hirschfeld, whose life was dedicated to social progress for people who were transsexual, transvestite and homosexual, formed the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexology) in 1919. The institute conducted an enormous amount of research, saw thousands of transgender and homosexual clients at consultations, and championed a broad range of sexual reforms including sex education, contraception and women's rights. However, the gains made in Germany would soon be drastically reversed with the rise of Nazism, and the institute and its library were destroyed in 1933. The Swiss journal Der Kreis was the only part of the movement to continue through the Nazi era.

USSR's Criminal Code of 1922 decriminalized homosexuality.[30] This was a remarkable step in the USSR at the time – which was very backward economically and socially, and where many conservative attitudes towards sexuality prevailed. This step was part of a larger project of freeing sexual relationships and expanding women's rights – including legalizing abortion, granting divorce on demand, equal rights for women, and attempts to socialize housework. During Stalin's era, however, USSR reverted all these progressive measures – re-criminalizing homosexuality and imprisoning gay men and banning abortion.

In 1928, English writer Radclyffe Hall published a novel titled The Well of Loneliness. Its plot centers on Stephen Gordon, a woman who identifies herself as an invert after reading Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis, and lives within the homosexual subculture of Paris. The novel included a foreword by Havelock Ellis and was intended to be a call for tolerance for inverts by publicizing their disadvantages and accidents of being born inverted.[31] Hall subscribed to Ellis and Krafft-Ebing's theories and rejected (conservatively understood version of) Freud's theory that same-sex attraction was caused by childhood trauma and was curable.[32]

In the United States, several secret or semi-secret groups were formed explicitly to advance the rights of homosexuals as early as the turn of the 20th century, but little is known about them.[33] A better documented group is Henry Gerber's Society for Human Rights formed in Chicago in 1924, which was quickly suppressed.[34]

Homophile movement (1945–1969)

[edit]

Immediately following World War II, a number of homosexual rights groups came into being or were revived across the Western world, in Britain, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the Scandinavian countries and the United States. These groups usually preferred the term homophile to homosexual, emphasizing love over sex. The homophile movement began in the late 1940s with groups in the Netherlands and Denmark, and continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s with groups in Sweden, Norway, the United States, France, Britain and elsewhere. ONE, Inc., the first public homosexual organization in the U.S.,[35] was bankrolled by the wealthy transsexual man Reed Erickson. A U.S. transgender rights journal, Transvestia: The Journal of the American Society for Equality in Dress, also published two issues in 1952.

The homophile movement lobbied to establish a prominent influence in political systems of social acceptability. Radicals of the 1970s would later disparage the homophile groups for being assimilationist. Any demonstrations were orderly and polite.[36] By 1969, there were dozens of homophile organizations and publications in the U.S.,[37] and a national organization had been formed, but they were largely ignored by the media. A 1965 gay march held in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, according to some historians, marked the beginning of the modern gay rights movement. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, the LGBT youth organization Vanguard was formed by Adrian Ravarour to demonstrate for equality, and Vanguard members protested for equal rights during the months of April–July 1966, followed by the August 1966 Compton's riot, where transgender street prostitutes in the poor neighborhood of Tenderloin rioted against police harassment at a popular all-night restaurant, Gene Compton's Cafeteria.[38]

The Wolfenden Report was published in Britain on September 4, 1957, after publicized convictions for homosexuality of well-known men, including Edward Montagu-Scott, 3rd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu. Disregarding the conventional ideas of the day, the committee recommended that "homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence". All but James Adair were in favor of this and, contrary to some medical and psychiatric witnesses' evidence at that time, found that "homosexuality cannot legitimately be regarded as a disease, because in many cases it is the only symptom and is compatible with full mental health in other respects." The report added, "The law's function is to preserve public order and decency, to protect the citizen from what is offensive or injurious, and to provide sufficient safeguards against exploitation and corruption of others ... It is not, in our view, the function of the law to intervene in the private life of citizens, or to seek to enforce any particular pattern of behavior."

The report eventually led to the introduction of the Sexual Offences Bill 1967 supported by Labour MP Roy Jenkins, then the Labour Home Secretary. When passed, the Sexual Offenses Act decriminalized homosexual acts between two men over 21 years of age in private in England and Wales. The seemingly innocuous phrase 'in private' led to the prosecution of participants in sex acts involving three or more men, e.g. the Bolton 7 who were so convicted as recently as 1998.[39]

Bisexual activism became more visible toward the end of the 1960s in the United States. In 1966 bisexual activist Robert A. Martin (also known as Donny the Punk) founded the Student Homophile League at Columbia University and New York University. In 1967 Columbia University officially recognized this group, thus making them the first college in the United States to officially recognize a gay student group.[40] Activism on behalf of bisexuals in particular also began to grow, especially in San Francisco. One of the earliest organizations for bisexuals, the Sexual Freedom League in San Francisco, was facilitated by Margo Rila and Frank Esposito beginning in 1967.[40] Two years later, during a staff meeting at a San Francisco mental health facility serving LGBT people, nurse Maggi Rubenstein came out as bisexual. Due to this, bisexuals began to be included in the facility's programs for the first time.[40]

Gay Liberation movement (1969–1974)

[edit]The new social movements of the sixties, such as the Black Power and anti-Vietnam war movements in the US, the May 1968 insurrection in France, and Women's Liberation throughout the Western world, inspired many LGBT activists to become more radical,[36] and the Gay Liberation movement emerged towards the end of the decade. This new radicalism is often attributed to the Stonewall riots of 1969, when a group of gay men, lesbians, drag queens and transgender women at a bar in New York City resisted a police raid.[34]

Immediately after Stonewall, such groups as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists' Alliance (GAA) were formed. Their use of the word gay represented a new unapologetic defiance—as an antonym for straight ("respectable sexual behavior"), it encompassed a range of non-normative sexuality and sought ultimately to free the bisexual potential in everyone, rendering obsolete the categories of homosexual and heterosexual.[41][42] According to Gay Lib writer Toby Marotta, "their Gay political outlooks were not homophile but liberationist".[43] "Out, loud and proud," they engaged in colorful street theater.[44] The GLF's "A Gay Manifesto" set out the aims for the fledgling gay liberation movement, and influential intellectual Paul Goodman published "The Politics of Being Queer" (1969). Chapters of the GLF were established across the U.S. and in other parts of the Western world. The Front homosexuel d'action révolutionnaire was formed in 1971 by lesbians who split from the Mouvement Homophile de France.

The Gay liberation movement overall, like the gay community generally and historically, has had varying degrees of gender nonconformity and assimilationist platforms among its members. Early marches by the Mattachine society and Daughters of Bilitis stressed looking "respectable" and mainstream, and after the Stonewall Uprising the Mattachine Society posted a sign in the window of the club calling for peace. Gender nonconformity has always been a primary way of signaling homosexuality and bisexuality, and by the late 1960s and mainstream fashion was increasingly incorporating what by the 1970s would be considered "unisex" fashions. In 1970, the drag queen caucus of the GLF, including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, formed the group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), which focused on providing support for gay prisoners, housing for homeless gay youth and street people, especially other young "street queens".[45][46][47] In 1969, Lee Brewster and Bunny Eisenhower formed the Queens Liberation Front (QLF), partially in protest to the treatment of the drag queens at the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March.[47]

One of the values of the movement was gay pride. Within weeks of the Stonewall Riots, Craig Rodwell, proprietor of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in lower Manhattan, persuaded the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) to replace the Fourth of July Annual Reminder at Independence Hall in Philadelphia with a first commemoration of the Stonewall Riots. Liberation groups, including the Gay Liberation Front, Queens, the Gay Activists Alliance, Radicalesbians, and Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR) all took part in the first Gay Pride Week. Los Angeles held a big parade on the first Gay Pride Day. Smaller demonstrations were held in San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston.[48][49]

In the United Kingdom the GLF had its first meeting in the basement of the London School of Economics on October 13, 1970. Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter had seen the effect of the GLF in the United States and created a parallel movement based on revolutionary politics and alternative lifestyle.[50]

By 1971, the UK GLF was recognized as a political movement in the national press, holding weekly meetings of 200 to 300 people.[51] The GLF Manifesto was published, and a series of high-profile direct actions, were carried out.[52]

The disruption of the opening of the 1971 Festival of Light was the best organized of GLF action. The Festival of Light, whose leading figures included Mary Whitehouse, met at Methodist Central Hall. Groups of GLF members in drag invaded and spontaneously kissed each other; others released mice, sounded horns, and unveiled banners, and a contingent dressed as workmen obtained access to the basement and shut off the lights.[53]

In 1972, Sweden became the first country in the world to allow people who were transsexual by legislation to surgically change their sex and provide free hormone replacement therapy. Sweden also permitted the age of consent for same-sex partners to be at age 15, making it equal to heterosexual couples.[54]

Bisexuals became more visible in the LGBT rights movement in the 1970s. In 1972 a Quaker group, the Committee of Friends on Bisexuality, issued the "Ithaca Statement on Bisexuality" supporting bisexuals.[55]

The Statement, which may have been "the first public declaration of the bisexual movement" and "was certainly the first statement on bisexuality issued by an American religious assembly," appeared in the Quaker Friends Journal and The Advocate in 1972.[56][57][58]

In that same year the National Bisexual Liberation Group formed in New York.[59] In 1976 the San Francisco Bisexual Center opened.[59]tzerland started with Rosa von Praunheims movie It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives.

Easter 1972 saw the Gay Lib annual conference held in the Guild of Undergraduates Union (students union) building at the University of Birmingham.[60]

In May 1974 the American Psychiatric Association, after years of pressure from activists, changed the wording concerning homosexuality in the Sixth printing of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders from a "mental disorder" to that of a "sexual orientation disturbance". While still not a flattering description, it took gay people out of the category of being automatically considered mentally ill simply for their sexual orientation.[61][62]

By 1974, internal disagreements had led to the movement's splintering. Organizations that spun off from the movement included the London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard, Gay News, and Icebreakers. The GLF Information Service continued for a few further years providing gay related resources.[50] GLF branches had been set up in some provincial British towns (e.g., Bradford, Bristol, Leeds, and Leicester) and some survived for a few years longer. The Leicester group founded by Jeff Martin was noted for its involvement in the setting up of the local "Gayline", which is still active today and has received funding from the National Lottery. They also carried out a high-profile campaign against the local paper, the Leicester Mercury, which refused to advertise Gayline's services at the time.[63]

In Japan, LGBT groups were established in the 1970s.[64][65] In 1971, Ken Togo ran for the Upper House election.

LGBT rights movement (1974–present)

[edit]

1974–1986

[edit]From the radical Gay Liberation movement of the early 1970s arose a more reformist and single-issue Gay Rights movement, which portrayed gays and lesbians as a minority group and used the language of civil rights—in many respects continuing the work of the homophile period.[66] In Berlin, for example, the radical Homosexual Action West Berlin was eclipsed by the General Homosexual Working Group.[67]

Gay and lesbian rights advocates argued that one's sexual orientation does not reflect on one's gender; that is, "you can be a man and desire a man... without any implications for your gender identity as a man," and the same is true if you are a woman.[68] Gays and lesbians were presented as identical to heterosexuals in all ways but private sexual practices, and butch "bar dykes" and flamboyant "street queens" were seen as negative stereotypes of lesbians and gays. Veteran activists such as Sylvia Rivera and Beth Elliot were sidelined or expelled because they were transgender.

In 1974, Maureen Colquhoun came out as the first Lesbian Member of Parliament (MP) for the Labour Party in the UK. When elected she was married in a heterosexual marriage.[69]

In 1975, the groundbreaking film portraying homosexual gay icon Quentin Crisp's life, The Naked Civil Servant, was transmitted by Thames Television for the British Television channel ITV. The British journal Gay Left also began publication.[70] After British Home Stores sacked an openly gay trainee Tony Whitehead, a national campaign subsequently picketed their stores in protest.

In 1977, Harvey Milk was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors becoming the first openly gay man in the State of California to be elected to public office.[71] Milk was assassinated by a former city supervisor Dan White in 1978.[72]

In 1977, a former Miss America contestant and orange juice spokesperson, Anita Bryant, began a campaign "Save Our Children",[73] in Dade County, Florida (greater Miami), which proved to be a major setback in the Gay Liberation movement. Essentially, she established an organization which put forth an amendment to the laws of the county which resulted in the firing of many public school teachers on the suspicion that they were homosexual.

In 1979, a number of people in Sweden called in sick with a case of being homosexual, in protest of homosexuality being classified as an illness. This was followed by an activist occupation of the main office of the National Board of Health and Welfare. Within a few months, Sweden became the first country in the world to remove homosexuality as an illness.[74]

Between 1980 and 1988, the international gay community rallied behind Eliane Morissens, a Belgian lesbian who had been fired from her teaching post for coming out on television and bringing attention to employment discrimination.[75][76] The case prompted protests, articles, and fundraising events throughout Europe and the Americas.[77][78] Articles were carried in Toronto's The Body Politic,[79] the Gay Community News of Boston;[80] and the San Francisco Sentinel.[81] The French magazine Gai pied created a support network to organize demonstrations and launched a petition drive for subscribers and members of the International Gay Association (IGA) to call on the Council of Europe to renounce discrimination against homosexuals.[82] The International Lesbian Information Service (ILIS) published information in their newsletter about letter-writing campaigns, and organized fund-raisers and solidarity protests to help pay for Morissens' legal and personal expenses and bring attention to the case.[83] Both ILIS and IGA lobbied European teachers' unions in support of Morissens.[83][84] Though Morissens appealed the school board decision to the local council; the highest court in Belgium, Council of State; and the European Court of Human Rights, her termination was upheld at every level.[75] The LGBT community was disappointed in the outcome because each court of appeal refused to recognize or examine whether employment discrimination had occurred, accepting the employer's version of events, and narrowly examining freedom of expression.[77][85]

Lesbian feminism, which was most influential from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, encouraged women to direct their energies toward other women rather than men, and advocated lesbianism as the logical result of feminism.[86] As with Gay Liberation, this understanding of the lesbian potential in all women was at odds with the minority-rights framework of the Gay Rights movement. Many women of the Gay Liberation movement felt frustrated at the domination of the movement by men and formed separate organisations; some who felt gender differences between men and women could not be resolved developed "lesbian separatism," influenced by writings such as Jill Johnston's 1973 book Lesbian Nation. Organizers at the time focused on this issue. Diane Felix, also known as DJ Chili D in the Bay Area club scene, is a Latino American lesbian once joined the Latino American queer organization GALA. She was known for creating entertainment spaces specifically for queer women, especially in Latino American community. These places included gay bars in San Francisco such as A Little More and Colors.[87] Disagreements between different political philosophies were, at times, extremely heated, and became known as the lesbian sex wars,[88] clashing in particular over views on sadomasochism, prostitution and transsexuality. The term "gay" came to be more strongly associated with homosexual males.

In Canada, the coming into effect of Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1985 saw a shift in the gay rights movement in Canada, as Canadian gays and lesbians moved from liberation to litigious strategies. Premised on Charter protections and on the notion of the immutability of homosexuality, judicial rulings rapidly advanced rights, including those that compelled the Canadian government to legalize same-sex marriage. It has been argued that while this strategy was extremely effective in advancing the safety, dignity and equality of Canadian homosexuals, its emphasis of sameness came at the expense of difference and may have undermined opportunities for more meaningful change.[89]

Mark Segal, often referred to as the dean of American gay journalism, disrupted the CBS evening news with Walter Cronkite in 1973,[90] an event covered in newspapers across the country and viewed by 60% of American households, many seeing or hearing about homosexuality for the first time.

Another setback in the United States occurred in 1986, when the US Supreme Court upheld a Georgia anti-sodomy law in the case Bowers v. Hardwick. (This ruling would be overturned two decades later in "Lawrence v. Texas").

1987–2000

[edit]

AIDS pandemic

[edit]Some historians posit that a new era of the gay rights movement began in the 1980s with the emergence of AIDS. As gay men became seriously ill and died in ever-increasing numbers, and many lesbian activists became their caregivers, the leadership of many organizations was decimated. Other organizations shifted their energies to focus their efforts on AIDS.[35] This era saw a resurgence of militancy with direct action groups like AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), formed in 1987, as well as its offshoots Queer Nation (1990) and the Lesbian Avengers (1992). Some younger activists, seeing gay and lesbian as increasingly normative and politically conservative, began using queer as a defiant statement of all sexual minorities and gender variant people—just as the earlier liberationists had done with gay. Less confrontational terms that attempt to reunite the interests of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people also became prominent, including various acronyms like LGBT, LGBTQ, and LGBTI, where the Q and I stand for queer or questioning and intersex, respectively.

Warrenton "War Conference"

[edit]A "War Conference" of 200 gay leaders was held in Warrenton, Virginia, in 1988.[91] The closing statement of the conference set out a plan for a media campaign:[92][93]

First, we recommend a nation-wide media campaign to promote a positive image of gays and lesbians. Every —national, state, and local—must accept the responsibility. We must consider the media in every project we undertake. We must, in addition, take every advantage we can to include public service announcements and paid advertisements, and to cultivate reporters and editors of newspapers, radio, and television. To help facilitate this we need national media workshops to train our leaders. And we must encourage our gay and lesbian press to increase coverage of the national process. Our media efforts are fundamental to the full acceptance of us in American life. But they are also a way for us to increase the funding of our movement. A media campaign costs money, but ultimately it may be one of our most successful fund-raising devices.

The statement also called for an annual planning conference "to help set and modify our national agenda."[93] The Human Rights Campaign lists this event as a milestone in gay history and identifies it as where National Coming Out Day originated.[94]

On June 24, 1994, the first Gay Pride march was celebrated in Asia in the Philippines.[95] In the Middle East, LGBT organizations remain illegal, and LGBT rights activists face extreme opposition from the state.[96] The 1990s also saw the emergence of many LGBT youth movements and organizations such as LGBT youth centers, gay–straight alliances in high schools, and youth-specific activism, such as the National Day of Silence. Colleges also became places of LGBT activism and support for activists and LGBT people in general, with many colleges opening LGBT centers.[97]

The 1990s also saw a rapid push of the transgender movement, while at the same time a "sidelining of the identity of those who are transsexual." In the English-speaking world, Leslie Feinberg published Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come in 1992.[98] Gender-variant peoples across the globe also formed minority rights movements. Hijra activists campaigned for recognition as a third sex in India and Travesti groups began to organize against police brutality across Latin America while activists in the United States formed direct-confrontation groups such as the Transexual Menace.

21st century

[edit]Same-sex marriage

[edit]

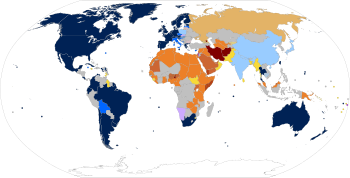

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression, not enforced |

Restrictions of association with arrests or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years[timeframe?] or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

As of 2025[update], same-sex marriages are recognized in Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay.[99]

The Netherlands was the first country to allow same-sex marriage in 2001. Following with Belgium in 2003 and Spain and Canada in 2005.[100] South Africa became the first African nation to legalize same-sex marriage in 2006, and is currently the only African nation where same-sex marriage is legal.[101][102] Despite this uptick in tolerance of the LGBT community in South Africa, so-called corrective rapes have become prevalent in response, primarily targeting the poorer women who live in townships and those who have no recourse in responding to the crimes because of the notable lack of police presence and prejudice they may face for reporting assaults.[102]

On 22 October 2009, the assembly of the Church of Sweden, voted strongly in favour of giving its blessing to homosexual couples,[103] including the use of the term marriage, ("matrimony").

Iceland became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage through a unanimous vote: 49–0, on 11 June 2010.[104] A month later, Argentina became the first country in Latin America to legalize same-sex marriage.

On 26 June 2015, in Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-to-4 that the Constitution requires that same-sex couples be allowed to marry no matter where they live in the United States.[105] With this ruling, the United States became the 17th country to legalize same-sex marriages entirely.[106]

Between 12 September and 7 November 2017, Australia held a national survey on the subject of same sex marriage; 61.6% of respondents supported legally recognizing same-sex marriage nationwide.[107] This cleared the way for a private member's bill to be debated in the federal parliament.

In 2019, Taiwan became the first country in Asia to allow same-sex marriage.[108][109][110] There has been a legal movement attempting to recognise marriage equality in Japan.[111][112]

Other rights

[edit]In 2003, in the case Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down sodomy laws in fourteen states, making consensual homosexual sex legal in all 50 states, a significant step forward in LGBT activism and one that had been fought for by activists since the inception of modern LGBT social movements.[113]

From November 6 to 9, 2006, The Yogyakarta Principles on application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity was adopted by an international meeting of 29 specialists in Yogyakarta,[114] the International Commission of Jurists and the International Service for Human Rights.[115]

During this same period, some municipalities have been enacting laws against homosexuality. For example, Rhea County, Tennessee, unsuccessfully tried to "ban homosexuals" in 2006.[116]

The 1993 "Don't ask, don't tell" law, forbidding homosexual people from serving openly in the United States military, was repealed in 2010.[117] This meant that gays and lesbians could now serve openly in the military without any fear of being discharged because of their sexual orientation. In 2012, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development's Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity issued a regulation to prohibit discrimination in federally-assisted housing programs. The new regulations ensure that the department's core housing programs are open to all eligible persons, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

The UN declaration on sexual orientation and gender identity gathered 66 signatures in the United Nations General Assembly on December 13, 2008.[118] In early 2014 a series of protests organized by Add The Words, Idaho, and former state senator Nicole LeFavour, some including civil disobedience and concomitant arrests,[119] took place in Boise, Idaho, which advocated adding the words "sexual orientation" and "gender identity" to the state's Human Rights act.[120][121][122]

On September 6, 2018, consensual gay sex was legalized in India by their Supreme Court.[123]

In June 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the 1964 Civil Rights Act could protect gay and transgender people from workplace discrimination. The Bostock v. Clayton County decision found that protections guaranteed on the basis of sex could extend to sexual orientation and identity in areas like housing and employment.[124] Democrats such as then-presidential candidate Joe Biden praised the decision.[124]

Today, by affirming that sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination are prohibited under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the Supreme Court has confirmed the simple but profoundly American idea that every human being should be treated with respect and dignity.

Due to a lack of federal protections, discrimination against LGBT people in public accommodation or the sale of goods and services by private businesses remains legal, leaving vulnerable those in more than half the states in the U.S.[125]

In October 2020, the Council of Europe's Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) Unit, along with the European Court of Human Rights, held a conference to mark the 70th anniversary of the European Convention on Human Rights on October 8, 2020. The entity announced launching an event called "A 'Living Instrument' for Everyone: The Role of the European Convention on Human Rights in Advancing Equality for LGBTI persons", focused on the progress achieved in equality for LGBTI persons in Europe through the European Convention mechanism.[126]

President Biden signed an executive order barring LGBTQ discrimination on his first day in office.[127] Later the same year, Biden reversed a Trump-era policy of banning transgender people from the military, authorized embassies to fly the pride flag, and officially recognized June as Pride Month.[128]

LGBT and human rights

[edit]Some people worry that gay rights conflict with individuals' freedom of speech,[129][130][131] religious freedoms in the workplace,[132][133] and the ability to run churches,[134] charitable organizations[135][136] and other religious organizations[137] that hold opposing social and cultural views to LGBT rights. There is also concern that religious organizations might be forced to accept and perform same-sex marriages or risk losing their tax-exempt status.[138][139][140][141]

Freedom of religion may, however, also protect LGBT people. As pointed out at the United Nations Human Rights Council in the 2023 formal report of the United Nations Independent Expert on sexual orientation and gender identity on the basis of the explanation in a 2020 article by human rights expert Dag Øistein Endsjø, adherents of denominations and belief systems who embrace LGBT-equality "can claim that anti-LGBT manifestations of religion (such as criminalization and discrimination) not only impinge upon the right of LGBT people to be free from violence and discrimination based on SOGI [sexual orientation and gender identity], but also violate the [pro-LGBT] denominations' own rights of freedom of religion". As pointed out in this article, freedom of religion also generally protects LGBT people against religious oppression, as freedom of religion also protects the “freedom ... not to hold religious beliefs and ... not to practise a religion”.[142] As the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief noted in 2017, “in certain States where religion has been given ‘official’ or privileged status, other fundamental rights of individuals – especially women, religious minorities and members of the LGBTI community – are disproportionately restricted or vitiated under threat of sanctions as a result of obligatory observation of State-imposed religious orthodoxy.”[143]

Public opinion

[edit]

LGBT movements are opposed by a variety of individuals and organizations.[144][145][146][147][148] They may have a personal, political or religious prejudice to gay rights, homosexual relations or gay people. Opponents say same-sex relationships are not marriages,[149] that legalization of same-sex marriage will open the door for the legalization of polygamy,[150] that it is unnatural[151] and that it encourages unhealthy behavior.[152][153] Some social conservatives believe that all sexual relationships with people other than an opposite-sex spouse undermines the traditional family[154] and that children should be reared in homes with both a father and a mother.[155][156] As society in some countries (mostly in Western Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Taiwan) has become more accepting of homosexuality, there therefore has also been the emergence of many groups that desire to end homosexuality; during the 1990s, one of the best known groups that was established with this goal is the ex-gay movement.

Eric Rofes author of the book, A Radical Rethinking of Sexuality and Schooling: Status Quo or Status Queer?, argues that the inclusion of teachings on homosexuality in public schools will play an important role in transforming public ideas about lesbian and gay individuals.[157] As a former teacher in the public school system, Rofes recounts how he was fired from his teaching position after making the decision to come out as gay. As a result of the stigma that he faced as a gay teacher he emphasizes the necessity of the public to take radical approaches to making significant changes in public attitudes about homosexuality.[157] According to Rofes, radical approaches are grounded in the belief that "something fundamental needs to be transformed for authentic and sweeping changes to occur. "The radical approaches proposed by Rofes have been met with strong opposition from anti-gay rights activists such as John Briggs. Former California senator, John Briggs proposed Proposition 6, a ballot initiative that would require that all California state public schools fire any gay or lesbian teachers or counselors, along with any faculty that displayed support for gay rights in an effort to prevent what he believe to be "the corruption of the children's minds".[158] The exclusion of homosexuality from the sexual education curriculum, in addition to the absence of sexual counseling programs in public schools, has resulted in increased feelings of isolation and alienation for gay and lesbian students who desire to have gay counseling programs that will help them come to terms with their sexual orientation.[157] Eric Rofes founder of youth homosexual programs, such as Out There and Committee for Gay Youth, stresses the importance of having support programs that help youth learn to identify with their sexual orientation.

David Campos, author of the book, Sex, Youth, and Sex Education: A Reference Handbook, illuminates the argument proposed by proponents of sexual education programs in public schools.[159] Many gay rights supporters argue that teachings about the diverse sexual orientations that exist outside of heterosexuality are pertinent to creating students that are well informed about the world around them. However, Campos also acknowledges that the sex education curriculum alone cannot teach youth about factors associated with sexual orientation but instead he suggests that schools implement policies that create safe school learning environments and foster support for LGBT youth.[160] It is his belief that schools that provide unbiased, factual information about sexual orientation, along with supportive counseling programs for these homosexual youth will transform the way society treats homosexuality.[160]

Many opponents of LGBT social movements have attributed their indifference toward homosexuality as being a result of the immoral values that it may instill in children who are exposed to homosexual individuals.[158] In opposition to this claim, many proponents of increased education about homosexuality suggest that educators should refrain from teaching about sexuality in schools entirely. In her book entitled "Gay and Lesbian Movement," Margaret Cruikshank provides statistical data from the Harris and Yankelovich polls which confirmed that over 80% of American adults believe that students should be educated about sexuality within their public school. In addition, the poll also found that 75% of parents believe that homosexuality and abortion should be included in the curriculum as well. An assessment conducted on California public school systems discovered that only 2% of all parents actually disapproved of their child being taught about sexuality in school.[161]

It had been suggested that education has a positive impact on support for same sex marriage. African Americans statistically have lower rates of educational achievement; however, the education level of African Americans does not have as much significance on their attitude towards same-sex marriage as it does on white attitudes. Educational attainment among whites has a significant positive effect on support for same-sex marriage, whereas the direct effect of education among African Americans is less significant. The income levels of whites have a direct and positive correlation with support for same-sex marriage, but African American income level is not significantly associated with attitudes toward same-sex marriage.[162]

Location also affects ideas towards same-sex marriage; residents of rural and southern areas are significantly more opposed to same-sex marriage in comparison to residents elsewhere. Gays and lesbians that live in rural areas face many challenges, including: sparse populations and the traditional culture held closely by the small population of most rural areas, generally hostile social climates towards gays relative to urban areas, and less social and institution support and access compared to urban areas.[163] In order to combat this problem that the LGBT community faces, social networks and apps such as Moovs have been created for "LGBT individuals with like-minds" that are "enabled to connect, share, and feel the heartbeat of the community as one."[164][165]

In a study conducted by Darren E. Sherkat, Kylan M. de Vries, and Stacia Creek at the Southern Illinois University Carbondale, researchers found that women tend to be more consistently supportive of LGBT rights than men and that individuals that are divorced or have never married are also more likely to grant marital rights to same-sex couples than married or widowed individuals. They also claimed that white women are significantly more supportive than white men, but there are no gender discrepancies among African Americans. The year in which one was born was also found to be a strong indicator of attitude towards same-sex marriage—generations born after 1946 are considerably more supportive of same-sex marriage than older generations. Finally, the study reported that statistically African Americans are more opposed to same-sex marriage than any other ethnicity.[162]

Studies show that Non-Protestant Christians are much more likely to support same-sex unions than Protestants; 63% of African Americans claim that they are Baptist or Protestant, whereas only 30% of white Americans are. Religion, as measured by individuals' religious affiliations, behaviors, and beliefs, has a lot of influence in structuring same-sex union attitudes and consistently influences opinions about homosexuality. The most liberal attitudes are generally reflected by Jews, liberal Protestants, and people who are not affiliated with religion. This is because many of their religious traditions have not "systematically condemned homosexual behaviors" in recent years. Moderate and tolerant attitudes are generally reflected by Catholics and moderate Protestants. And lastly, the most conservative views are held by Evangelical Protestants. Moreover, it is a tendency for one to be less tolerant of homosexuality if their social network is strongly tied to a religious congregation. Organized religion, especially Protestant and Baptist affiliations, espouse conservative views which traditionally denounce same-sex unions. Therefore, these congregations are more likely to hear messages of this nature. Polls have also indicated that the amount and level of personal contact that individuals have with homosexual individuals and traditional morality affects attitudes of same-sex marriage and homosexuality.[166]

References

[edit]- ^ Julia Goicichea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Whisnant, Clayton J. (2016). Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880–1945. Columbia University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-939594-10-5.

- ^ Bernstein, Mary (2002). "Identities and Politics: Toward a Historical Understanding of the Lesbian and Gay Movement". Social Science History. 26 (3): 531–581. doi:10.1017/S0145553200013080. JSTOR 40267789. S2CID 151848248.

- ^ Kitchen, Julian; Bellini, Christine (2012). "Addressing Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Issues in Teacher Education: Teacher Candidates' Perceptions". Alberta Journal of Educational Research. 58 (3): 444–460. doi:10.55016/ojs/ajer.v58i3.55632. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Bull, C., and J. Gallagher (1996) Perfect Enemies: The Religious Right, the Gay Movement, and the Politics of the 1990s. New York: Crown.[page needed]

- ^ Parker, Richard G. (June 2007). "Sexuality, Health, and Human Rights". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (6): 972–973. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.113365. PMC 1874191. PMID 17463362.

- ^ Roffee, James A.; Waling, Andrea (October 10, 2016). "Rethinking microaggressions and anti-social behaviour against LGBTIQ+ youth". Safer Communities. 15 (4): 190–201. doi:10.1108/SC-02-2016-0004.

- ^ Balsam, Kimberly F.; Molina, Yamile; Beadnell, Blair; Simoni, Jane; Walters, Karina (April 2011). "Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale". Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 17 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1037/a0023244. PMC 4059824. PMID 21604840.

- ^ One example of this approach is: Sullivan, Andrew (1997). Same-Sex Marriage: Pro and Con. New York: Vintage.[page needed]

- ^ Bernstein (2002)

- ^ "This Alien Legacy". Human Rights Watch. December 17, 2008.

- ^ Robinson, David M. (2006). Closeted writing and lesbian and gay literature: classical, early modern, eighteenth-century. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7546-5550-3.

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy (1978). "Offences Against One's Self". Journal of Homosexuality. 3 (4). Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Blasius, Mark and Phelan, Shane (eds.), 1997. "We Are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics", New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-90859-0

- ^ "Poland" (PDF). GLBTQ. 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "British Library". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Joseph, Channing Gerard (January 31, 2020). "The First Drag Queen Was a Former Slave". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Heloise Wood (July 9, 2018). "'Extraordinary' tale of 'first' drag queen to Picador". The Bookseller. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Dynes, Wayne R., ed. (2016). The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality. Volume II. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. p. 1353.

- ^ a b Ives, George Cecil. "George Cecil Ives: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". Harry Ransom Center.

- ^ McKenna, Neil (2003), "The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde: An Intimate Biography". (London: Century) ISBN 0-7126-6986-8

- ^ Katz. Love Stories. pp. 243–244.

- ^ DeJean, "Sex and Philology," p. 132, pointing to the phrase "homosexual relations" (here as it appears in the later 1908 edition).

- ^ Robert Aldrich (1993). The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art, and Homosexual Fantasy. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 9780415093125.

- ^ Das Konträre Geschlechtsgefühle. Leipzig, 1896. See White, Chris (1999). Nineteenth-Century Writings on Homosexuality. CRC Press. p. 66.

- ^ Domeier, Norman (2014). "The Homosexual Scare and the Masculinization of German Politics before World War I". Central European History. 47 (4): 737–759. doi:10.1017/S0008938914001903. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 43965084. S2CID 146627960.

- ^ Breger, Claudia (2005). "Feminine Masculinities: Scientific and Literary Representations of 'Female Inversion' at the Turn of the Twentieth Century". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 14 (1): 76–106. doi:10.1353/sex.2006.0004. S2CID 142942952.

- ^ Dan Healey (October 15, 2001). Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. University of Chicago Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-226-32233-9. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- ^ Faderman (1981), p. 320.

- ^ Doan, p. XIII.

- ^ Norton, Rictor, (2005), "The Suppression of Lesbian and Gay History"

- ^ a b Bullough, Vern, "When Did the Gay Rights Movement Begin?", April 18, 2005

- ^ a b Percy, William A. & William Edward Glover, 2005, Before Stonewall, November 5, 2005 Archived June 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Matzner, 2004, "Stonewall Riots Archived January 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Percy, 2005, "Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights" Archived August 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernadicou, August. "Adrian Ravarour". August Nation. The LGBTQ History Project. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ "Pride 2010: From section 28 to Home Office float, Tories come out in force", Helen Pidd, The Guardian, London, July 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Timeline: the bisexual health movement in the US". BiNetUSA. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Altman, D. (1971). Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. New York: Outerbridge & Dienstfrey.

- ^ Adam, B. D. (1987). The rise of a gay and lesbian movement. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- ^ Marotta, Toby (1981). The Politics of Homosexuality. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 68. ISBN 9780395294772.

- ^ Gallagher, John; Bull, Chris (1996). "Perfect Enemies". WashingtonPost.com.

- ^ Shepard, Benjamin Heim and Ronald Hayduk (2002) From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization. Verso. pp.156–160 ISBN 978-1859-8435-67

- ^ Feinberg, Leslie (September 24, 2006). "Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries". Workers World Party. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

Stonewall combatants Sylvia Rivera and Marsha "Pay It No Mind" Johnson ... Both were self-identified drag queens.

- ^ a b Stryker, Susan (2018). Transgender History: the roots of today's revolution (Second ed.). New York, NY: Seal Press. pp. 68, 77, 110. ISBN 9781580056892. OCLC 990183211.

- ^ Waters, Michael. "The First Pride Marches, in Photos". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Kaufman, David (June 16, 2020). "How the Pride March Made History". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Lucas, Ian (1998), OutRage!: an oral history, Cassell, pp. 2–3, ISBN 978-0-304-33358-5

- ^ Victoria Brittain (August 28, 1971). "An Alternative to Sexual Shame: Impact of the new militancy among homosexual groups". The Times. p. 12.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front (GLF)". Database of Archives of Non-Government Organisations. Archived from the original on March 16, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Gingell, Basil (September 10, 1971). "Uproar at Central Hall as demonstrators threaten to halt Festival of Light". The Times. p. 14.

- ^ Hanna Jedvik (March 5, 2007). "Lagen om könsbyte ska utredas". RFSU. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ "June 1972: The Ithaca Statement". BiMedia. February 10, 2012. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015.

- ^ Donaldson, Stephen (1995). "The Bisexual Movement's Beginnings in the 70s: A Personal Retrospective". In Tucker, Naomi (ed.). Bisexual Politics: Theories, Queries, & Visions. New York: Harrington Park Press. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-1-56023-869-0.

- ^ Highleyman, Liz (July 11, 2003). "PAST Out: What is the history of the bisexual movement?". LETTERS From CAMP Rehoboth. Vol. 13, no. 8. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Martin, Robert (August 2, 1972). "Quakers 'come out' at conference". The Advocate (91): 8.

- ^ a b "LGBT History Timeline". United Church of Christ. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ "Gay Birmingham Remembered – The Gay Birmingham History Project". Birmingham LGBT Community Trust. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

Birmingham hosted the Gay Liberation Front annual conference in 1972, at the chaplaincy at Birmingham University Guild of Students.

- ^ Mayes, Rick; Bagwell, Catherine; Erkulwater, Jennifer L. (2009). "The Transformation of Mental Disorders in the 1980s: The DSM-III, Managed Care, and "Cosmetic Psychopharmacology"". Medicating Children: ADHD and Pediatric Mental Health. Harvard University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-674-03163-0. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Spitzer, R.L. (1981). "The diagnostic status of homosexuality in DSM-III: a reformulation of the issues". Am J Psychiatry. 138 (2): 210–215. doi:10.1176/ajp.138.2.210. PMID 7457641.

- ^ Gay News (1978) No. 135; Peace News (January 13, 1978)

- ^ 「オトコノコのためのボーイフレンド」(1986)

- ^ LGBT social movements in Japan

- ^ Epstein, S. (1999). Gay and lesbian movements in the United States: Dilemmas of identity, diversity, and political strategy. in B. D. Adam, J. Duyvendak, & A. Krouwel (Eds.), "The global emergence of gay and lesbian politics" (pp. 30–90). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- ^ Hekman, Gert; Oosterhuis, Harry; Steakley, James (1995). "Leftist Sexual Politics and Homosexuality: A Historical Overview". Journal of Homosexuality. 29 (2): 1–40. doi:10.1300/J082v29n02_01. PMID 8666751.

- ^ David Valentine, "'I Know What I Am': The Category 'Transgender' in the Construction of Contemporary U.S. American Conceptions of Gender and Sexuality" (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2000), p. 190.

- ^ "Where are they now: Maureen Colquhoun". Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ The Knitting Circle Archived January 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – 'Gay Left Collective'

- ^ Friess, Steve (December 11, 2015). "The First Openly Gay Person to Win an Election in America Was Not Harvey Milk". bloomberg.com.

- ^ "Dan White Commits Suicide". The Washington Post. October 22, 1985. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Watch: The singer who helped launch the anti-gay rights movement". Timeline. December 14, 2017. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022.

- ^ Bergh, Frederick Quist (2001). "Jag känner mig lite homosexuell idag" [I feel a little gay today] (in Swedish). Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Council of Europe Staff (1992). "Case-law of the Commission: 2. Application No. 11389/85 Eliane Morissens v. Belgium". Yearbook of the European Convention on Human Rights, 1988. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 40–45. ISBN 978-0-7923-1787-6.

- ^ "Belgian High Court Backs Teacher's Firing". The Body Politic (112). Toronto, Ontario: Pink Triangle Press: 18. March 1985. ISSN 0315-3606. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Pastre, Geneviève (Spring 1982). "L'affaire Éliane Morissens, mise a la retraite d'office pour homosexualité" [The Éliane Morissens Case: Automatically Retired for Homosexuality]. Masques (in French) (13). Paris: Association Masques: 104–105. ISSN 0981-9614. Retrieved June 3, 2022 – via Gallica.

- ^ "Lesbienne krijgt steun" [Lesbian Gets Support]. Het Parool (in Dutch). No. 11348. Amsterdam, the Netherlands. January 22, 1982. p. 7. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ "Belgian Teacher Ends 38-Day Hunger Strike". The Body Politic (82). Toronto, Ontario: Pink Triangle Press: 20. April 1982. ISSN 0315-3606. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "Belgian Socialist Statement Tells Stand on Morrissens". Gay Community News. Vol. 9, no. 38. Boston, Massachusetts. April 17, 1982. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Lester, David (February 18, 1982). "Pickets Support Fired Belgian Teacher" (PDF). The Sentinel. Vol. 9, no. 7. San Francisco, California. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Pinhas, Luc (Fall 2011). "es ambivalences d'une entreprise de presse gaie: le périodique Gai Pied, de l'engagement au consumérisme" [The Ambivalences of a Gay Media Company: The Periodical Gai Pied, from Commitment to Consumerism] (PDF). Mémoires du livre / Studies in Book Culture (in French). 3 (1). Sherbrooke, Quebec: Groupe de recherches et d'études sur le livre au Québec. doi:10.7202/1007576ar. ISSN 1920-602X. OCLC 4894564457. S2CID 194089355. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Wilson, Ann Marie (January 2022). "Dutch Women and the Lesbian International". Women's History Review. 31 (1). Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge: 126–153. doi:10.1080/09612025.2021.1954338. ISSN 0961-2025. OCLC 9405931614. S2CID 240520862.

- ^ "The 1982 Congress of the International Gay Association adjourned..." United Press International. Boca Raton, Florida. April 12, 1982. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ Borghs, Paul (Fall 2016). "The Gay and Lesbian Movement in Belgium from the 1950s to the Present". QED. 3 (3). East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press: 29–70. doi:10.14321/qed.3.3.0029. ISSN 2327-1574. JSTOR 10.14321/qed.3.3.0029. OCLC 6951977288. S2CID 151750557.

- ^ Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. Signs, 5, 631–660.

- ^ Cassell, Heather. "Music's the life for Chili D." Bay Area Reporter. BAR Media Inc.

- ^ Lesbian Sex Wars Archived March 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, article by Elise Chenier from GLBTQ encyclopedia.

- ^ Lehman, M. (2005). Getting Gay Rights Straight.

- ^ Avery, Dan (June 5, 2012). "The Time Gay Activists Interrupted Walter Cronkite On The CBS Evening News". queerty.com. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Gay rights leaders gather in Virginia". United Press International. February 27, 1988.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin (September 19, 1989). "Gay Activists Divided on Whether to "Bring Out" Politicians". Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Final Statement of the War Conference, Airlie House, Warrenton, VA" (PDF). Cornell University Library. February 28, 1988.

- ^ "The History of Coming Out". Human Rights Campaign. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ "The first gay pride march in Asia". fridae.asia. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ AL (June 6, 2018). "How homosexuality became a crime in the Middle East". The Economist.

- ^ "List of Colleges with a LGBT Center". College Equality Index. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014.

- ^ Feinberg, Leslie. "Transgender Liberation: A movement whose time has come". Workers World. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Marriage Equality Around the World". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Eichler, Margrit. "Same-Sex Marriage in Canada".

- ^ "Empowering Spirits Foundation Applauds Passage of NH Marriage Equality Bill" (PDF). Empowering Spirits Foundation Press Release. June 3, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Toesland, Finbarr (April 2017). "Fighting for LGBT Rights in Nigeria". DIVA Magazine. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "Synod opened on same-sex marriages". DN.se. October 22, 2009. Archived from the original on December 26, 2009.

- ^ "Iceland's parliament unanimously approves gay marriage". PinkNews. June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Barnes, Robert (June 26, 2015). "Supreme Court rules gay couples nationwide have a right to marry". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (June 26, 2015). "What was the first country to legalize gay marriage?". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ Baidawi, Adam; Cave, Damien (November 14, 2017). "Australia Votes for Gay Marriage, Clearing Path to Legalization". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Taiwan gay marriage: Parliament legalises same-sex unions". BBC. May 17, 2019. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Taiwan legalizes same-sex marriage in historic first for Asia". CNN. May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Steger, Isabella (May 17, 2019). "In a first for Asia, Taiwan legalized same-sex marriage—with caveats". Quartz. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (June 8, 2023). "Japan court falls short of calling same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional". The Guardian.

- ^ "In Landmark Ruling, Court Says Japan's Ban On Same-Sex Marriage Is Unconstitutional". National Public Radio. March 17, 2021.

- ^ Cordova, Jeanne, When We Were Outlaws (2011) p 51-56.

- ^ "Foundation for Human Rights :: The Right to Equality and Non-discrimination – the Law". fhr.org.za. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "Yogyakarta Principles | International Commission of Jurists". March 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "Tenn. County Reverses On Gay Ban". CBS News. March 18, 2004. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Klapper, Ethan (July 19, 2013). "On This Day In 1993, Bill Clinton Announced 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell'". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "U.N. divided over gay rights declaration". Reuters. December 18, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ KTVB, KTVB.COM (February 4, 2014). "Lawyers donating their time to defend 'Add the Words' protesters". KTVB. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ AP (February 3, 2014). "Dozens of gay rights activists arrested in Idaho". USA TODAY. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ "Boise, Meridian, Nampa, Caldwell news by Idaho Statesman". Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ "Boise, Meridian, Nampa, Caldwell news by Idaho Statesman". Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Rajagopal, Krishnadas (September 6, 2018). "SC decriminalises homosexuality, says history owes LGBTQ community an apology". The Hindu.

- ^ a b Totenberg, Nina (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court Delivers Major Victory To LGBTQ Employees". NPR. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Idaho vs. United States | Population Trends over 1958-2021". Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "How the European Convention on Human Rights is advancing equality for LGBTI people". Council Of Europe. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ "Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation". White House. January 20, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Seddiq, Oma (June 1, 2021). "Biden formally recognizes LGBTQ Pride Month, restarting a tradition that Trump abandoned". Business Insider. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Gove, Michael (December 24, 2002). "I'd like to say this, but it might land me in prison". The Times. London. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008.

- ^ "Christian group likens Tory candidate review to witch hunt". CBC News. November 28, 2007. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007.

- ^ Kempling, Chris (April 9, 2008). "Conduct unbecoming a free society". National Post.[dead link]

- ^ Moldover, Judith (October 31, 2007). "Employer's Dilemma: When Religious Expression and Gay Rights Cross". New York Law Journal. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Ritter, Bob (January–February 2008). "Collision of religious and gay rights in the workplace". Humanist. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012.

- ^ "Bishop loses gay employment case". BBC News. July 18, 2007.

- ^ Beckford, Martin (June 5, 2008). "Catholic adoption service stops over gay rights". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ LeBlanc, Steve (March 10, 2006). "Catholic Charities to halt adoptions over issue involving gays". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009.

- ^ Mercer, Greg (April 24, 2008). "Christian Horizons rebuked: Employer ordered to compensate fired gay worker, abolish code of conduct". The Record. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ Gallagher, Maggie (May 15, 2006). "Banned in Boston:The coming conflict between same-sex marriage and religious liberty". Vol. 011, no. 33. Archived from the original on May 16, 2006. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ Capuzzo, Jill (August 14, 2007). "Church Group Complains of Civil Union Pressure". New York Times.

- ^ Capuzzo, Jill (September 18, 2007). "Group Loses Tax Break Over Gay Union Issue". New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Carrie (May 15, 2008). "LDS Church expresses disappointment in California gay marriage decision". Deseret News. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009.

- ^ United Nations Human Rights Council Freedom of religion or belief, and freedom from violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity: Report of the Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, 7 June 2023, § 162; Dag Øistein Endsjø “The other way around? How freedom of religion may protect LGBT rights”, The International Journal of Human Rights 24:10 (2020), pp. 1686-88; Buscarini and Others v. San Marino (1999), 24645/94, European Court of Human Rights, § 34; cf. United Nation Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 22, 1993, 2.

- ^ United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion and Belief, A/HRC/34/50, 17 January 2017, § 45.

- ^ Strauss, Lehman, Litt.D., F.R.G.S. "Homosexuality: The Christian Perspective" Archived April 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.