Queer art

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2020) |

Queer art, also known as LGBT+ art or queer aesthetics, broadly refers to modern and contemporary visual art practices that draw on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and various non-heterosexual, non-cisgender imagery and issues.[1][2][3] While by definition there can be no singular "queer art", contemporary artists who identify their practices as queer often call upon "utopian and dystopian alternatives to the ordinary, adopt outlaw stances, embrace criminality and opacity, and forge unprecedented kinships and relationships."[4] Queer art is also occasionally very much about sex and the embracing of unauthorised desires.[4]

Queer art is highly site-specific, with queer art practices emerging very differently depending on context, the visibility of which possibly ranging from being advocated for, to conversely being met with backlash, censorship, or criminalisation.[5] With sex and gender operating differently in various national, religious, and ethnic contexts, queer art necessarily holds varied meanings.[5]

While historically, the term 'queer' is a homophobic slur from the 1980s AIDS crisis in the United States, it has been since re-appropriated and embraced by queer activists and integrated into many English-speaking contexts, academic or otherwise.[4] International art practices by LGBT+ individuals are thus often placed under the umbrella term of 'queer art' within English-speaking contexts, even though they emerge outside the historical developments of the gender and identity politics of the United States in the 1980s.

'Queer art' has also been used to retroactively refer to the historic work of LGBT+ artists who practiced at a time before present-day terminology of 'lesbian', 'gay', 'bisexual' and 'trans' were recognised, as seen deployed in the 2017 exhibition by Tate, Queer British Art 1861–1967.[6] The term "queer" is situated in the politics of non-normative, gay, lesbian and bisexual communities, though it is not equivalent to such categories, and remains a fluid identity.[4]

Adhering to no particular style or medium, queer art practices may span performance art, video art, installation, drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, film, glass, and mixed media, among many others.[7]

Beginnings

[edit]Early queer-coded art

[edit]In A Queer Little History of Art, art historian Alex Pilcher notes that across the history of art, biographical information about queer artists are often omitted, downplayed or else interpreted under the assumption of a heterosexual identity.[8] For instance, "[t]he same-sex partner becomes the 'close friend.' The artistic comrade is made out as the heterosexual love interest", with "gay artists diagnosed as 'celibate,' 'asexual,' or 'sexually confused.'"[8]

During the interwar period, greater acceptance towards queer individuals could be seen in artistic urban centers such as Paris and Berlin.[7] In 1920s New York, speakeasies in Harlem and Greenwich Village welcomed gay and lesbian clients, and cafés and bars across Europe and Latin America, for instance, became host to artistic groups which allowed gay men to be integrated into the development of mainstream culture.[7] During this period, artists still developed visual codes to signify queerness covertly. Art historian Jonathan David Katz writes of Agnes Martin's abstract paintings as "a form of queer self-realization" which produces the tense, unreconciled equilibrium of her paintings such as in Night Sea (1963), speaking to her identity as a closeted lesbian.[9]

Katz has further interpreted the use of iconography in Robert Rauschenberg's combine paintings, such as a picture of Judy Garland in Bantam (1954) and references to the Ganymede myth in Canyon (1959), as allusions to the artist's identity as a gay man.[10] Noting Rauschenberg's relationship with Jasper Johns, art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon interprets Johns' monochrome encaustic White Flag (1955) in relation to the artist's experiences as a gay man in a repressive American society.[7] Graham-Dixon notes that "if [Johns] admitted he was gay he could go to jail. With White Flag he was saying America 'was the land where [...] your voice cannot be heard. This is the America we live in; we live under a blanket. We have a cold war here. This is my America.'"[7]

In 1962, the US had begun to decriminalise sodomy, and by 1967 the new Sexual Offences Act in the United Kingdom meant that consensual sex between men was no longer illegal.[7] However, many queer individuals still faced pressure to remain closeted, worsened by the Hollywood Production Code which censored and banned depictions of "sex perversion" from films produced and distributed in the US up until 1968.[7]

The director Rosa von Praunheim has made more than 100 films on queer topics since the late 1960s, some of which have been evaluated internationally. Some films are considered milestones in queer cinema. Von Praunheim is internationally recognized as an icon of queer cinema.[11]

Stonewall riots (1969)

[edit]A key turning point in attitudes towards the LGBT community would be marked by the Stonewall riots. At the early morning hours of June 28, 1969 in New York City, patrons of the gay tavern Stonewall Inn, other Greenwich Village lesbian and gay bars, and neighbourhood street people fought back when the police became violent during a police raid. This became a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the LGBT+ community, and the riots are widely considered to constitute one of the most important events leading to the gay liberation movement.[12][13][14]

The first Pride Parade was held a year after the riots, with marches now held annually across the world. Queer activist art, through posters, signs, and placards, served as a significant manifestation of queer art from this time.[7] For example, photographer Donna Gottschalk would be photographed by photojournalist Diana Davies at the first pride parade in 1970 in New York City, with Gottschalk defiantly holding a sign that read "I am your worst fear I am your best fantasy."[15]

Formulation of 'queer' identity

[edit]AIDS epidemic (1980s to early 1990s)

[edit]

In 1980s, the HIV/AIDS outbreak ravaged both the gay and arts communities. In the context of the US, journalist Randy Shilts would argue in his book, And the Band Played On, that the Ronald Reagan administration put off handling the crisis due to homophobia, with the gay community being correspondingly distrustful of early reports and public health measures, resulting in the infection of hundreds of thousands more. In a survey conducted on doctors from mid to late 1980s, a large number indicated that they did not have an ethical obligation to treat or care for patients with HIV/AIDS.[16] Right-wing journalists and tabloid newspapers in the US and UK stoked anxieties about the transmission of HIV by stigmatizing gay men.[7] Activist groups were a significant source of advocacy for legislation and policy change, with, for instance, the formation of ACT-UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power in 1987.

Many artists at the time thus acted in their capacity as activists, demanding to be heard by the government and medical institutions alike.[7] The Silence=Death Project, a six-person collective, drew from influences such as feminist art activism group, Guerrilla Girls, to produce the iconic Silence = Death poster, which was wheatpasted across the city and used by ACT-UP as a central image in their activist campaign.[17][18] Collective Gran Fury, which was established in 1988 by several members of ACT-UP, served as the organization's unofficial agitprop creator, producing guerrilla public art that drew upon the visual iconography of commercial advertisements, as seen in Kissing Doesn't Kill: Greed and Indifference Do (1989). Lesbian feminist art activist collective fierce pussy would also be founded in 1991, committed to art action in association with ACT-UP.[19]

Keith Haring notably deployed his practice to generate activism and advocate for awareness about AIDS in the final years of his life, as seen with the poster Ignorance = Fear (1989), or the acrylic on canvas painting Silence = Death (1989), both of which invoke the iconic poster and motto.[20][21]

Beyond the framework of activist art, photographer Nan Goldin would document this period of New York City in her seminal work, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which encompassed a 1985 slide show exhibition and a 1986 artist's book publication of photographs taken between 1979 and 1986, capturing post-Stonewall gay subculture of the time.[22][23] In 1989, British artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien would release his film work Looking for Langston, which celebrated black gay identity and desire through a nonlinear narrative that drew from 1920s Harlem Renaissance in New York as well as then-current contexts of the 1980s, with Robert Mapplethorpe's controversial photographs of black gay men shown in the film, for example.[24]

Félix González-Torres would create works into the early 1990s that responded to the AIDS crisis that continued to ravage the gay community. González-Torres' Untitled (1991) featured six black-and-white photographs of the artist's empty double bed, enlarged and posted as billboards throughout Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens in the winter of 1991.[25] A highly personal point-of-view made public, it underscored the absence of a queer body, with the work on display after a time when González-Torres' lover, Ross Laycock, had died from AIDS-related complications in January 1991.[25]

Re-appropriation of 'queer' and identity politics

[edit]Throughout the 1980s, the homophobic term of abuse, 'queer', began being widely used, appearing from sensationalised media reports to countercultural magazines, at bars and in zines, and showing up at alternative galleries and the occasional museum.[7] The concept was thus integrated into the academy, and re-appropriated as a form of pride by queer activists.[4]

From the spring of 1989, a coalition of Christian groups and conservative elected officials waged a media war on government funding of "obscene" art, objecting that money from a National Endowment for the Arts grant went to queer artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Karen Finley, stoking a culture war.[26] Mapplethorpe's 1988 retrospective, The Perfect Moment, which exhibited the photographer's portraits, interracial figure studies, and flower arrangements, would be a catalyst for the debate. Known for his black-and-white celebrity portraits, self-portraits, portraits of people involved in BDSM, and homoerotic portraits of black nude men, the explicit sexual imagery of Mapplethorpe's work sparked a debate on what taxpayer's money should fund.[25] US law would prevent federal money from being used to "promote, encourage or condone homosexual activities," which also led to AIDS programs being defunded.[7] From 1987, the central government in the UK would ban local councils from using public funds to "promote homosexuality".[7]

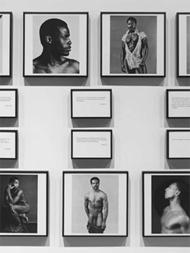

American conceptual artist Glenn Ligon provided an artistic response that critiqued both the conservative ideology that stoked the culture wars and Mapplethorpe's problematic imagery of queer black men.[27] Responding to Mapplethorpe's The Black Book (1988), a photographic series of homoerotic nude black men that failed to consider the subjects within broader histories of racialised violence and sexuality, Ligon created the work Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991-1993).[25] Shown at the 1993 Whitney Biennial, Ligon framed every page of Mapplethorpe's book in its original order, installing them in two rows on a wall, between them inserting around seventy framed texts relating to race from diverse sources, such as historians, philosophers, religious evangelists, activists, and curators.[25] By suggesting Mapplethorpe's work to be a projection of fears and desires upon the black male body, Ligon demonstrates the entanglement of sex, race, and desire, part of his larger practice of investigating the construction of black identity through words and images.[25]

Identity politics would thus further develop in response to right-wing, conservative and religious groups' attempts to suppress queer voices in public. Within the framework of identity politics, identity functions "as a tool to frame political claims, promote political ideologies, or stimulate and orient social and political action, usually in a larger context of inequality or injustice and with the aim of asserting group distinctiveness and belonging and gaining power and recognition."[28] Activist group the Gay Liberation Front would propose queer identity as a revolutionary form of social and sexual life that could disrupt traditional notions of sex and gender. More recently, however, critics have questioned the effectiveness of an identity politics consistently operates as a self-defined, oppositional "other".[7]

Running parallel with queer art are the discourses of feminism, which had paved the way for sex-positive queer culture and attempts to dismantle oppressive patriarchal norms.[7] For instance, the work of Catherine Opie operates strongly within a feminist framework, further informed by her identity as a lesbian woman, though she has stated that queerness does not entirely define her practice or ideas.[25] Opie's photography series, Being and Having (1991), involved capturing her friends in close-up frontal portraits, with assertive gazes against yellow backgrounds.[25] These subjects were chosen from Opie's group of friends, all of whom did not abide neatly by traditional gender categories.[25] Details such as adhesive visibly used to attach fake facial hair on female bodied people foregrounded the performative nature of gender.[25]

During the 1990s in Beijing, Chinese artist Ma Liuming would be involved with the Beijing East Village art community, founded in 1993.[29] In 1994, he would stage the performance art piece Fen-Ma + Liuming's Lunch (1994). The performance featured the artist assuming the persona of a transgender woman named Fen-Ma Liuming, who would prepare and serve steamed fish for the audience while completely nude, eventually sitting down and attaching a large laundry tube to her penis, sucking and breathing on the other end of the tube.[29] Ma would be arrested for such performances, and in 1995, police forced the artists to move out of Beijing's East Village, with Ma beginning to work outside China.[29]

The 21st century

[edit]Since the 2000s, queer practices continue to develop and be documented internationally, with a sustained emphasis on intersectionality,[25] where one's social and political identities such as gender, race, class, sexuality, ability, among others, might come together to create unique modes of discrimination and privilege.

Notable examples include New York and Berlin-based artist, filmmaker, and performer Wu Tsang, who re-imagines racialised, gendered representations, with her practice concerned with hidden histories, marginalised narratives, and the act of performing itself.[30] Her video work, WILDNESS (2012) constructs a portrait of a Latino Los Angeles LGBT bar, the Silver Platter, integrating elements of fiction and documentary to portray Tsang's complex relationship with the bar.[31] It further explores the impact of gentrification and a changing city on the bar's patrons, who are predominantly working class, Hispanic, and immigrant.[31]

Canadian performance artist Cassils is known for their 2012 body of work, Becoming An Image, which involves a performance where they direct a series of blows, kicks, and attacks to a 2000-pound clay block in total darkness, while the act is illuminated only by the flashes from a photographer.[32] The final photographs depict Cassils in an almost primal state, sweating, grimacing, and flying through the air as they pummel clay blocks, placing an emphasis on the physicality of their gender non-conforming and transmasculine body.[32][33] Another example includes New York-based artist, writer, performer, and DJ Juliana Huxtable, part of the queer arts collective, House of Ladosha, the artist exhibited her photographs with her poetry at the New Museum Triennial, with works such as Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm) from her Universal Crop Tops for All the Self Canonized Saints of Becoming series.[25] In it, Huxtable inhabits a futuristic world wherein she is able to reimagine herself apart from the trauma of her childhood, where she was assigned the male gender while being raised in a conservative Baptist home in Texas.[25]

Furthermore, while queer artists such as Zanele Muholi and Kehinde Wiley have had mid-career survey exhibitions at major museums, an artist's identity, gender and race are more commonly discussed than sexuality.[25] Wiley's sexuality, for instance, was not highlighted in his Brooklyn Museum retrospective.[25]

Spectrosynthesis – Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now

[edit]In 2017, a travelling show on Asian LGBTQ art, Spectrosynthesis – Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now, debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, Taiwan.[34] Coming shortly after the Taiwanese High Court's decision towards legalising same-sex marriage in May 2017, this would be one of the earliest art exhibitions to specifically focus on LGBTQ issues in a government-run institution in Asia.[35] The show exhibited 22 artists from Taiwan, China, Hong Kong and Singapore with a total of 51 artworks.[35] It would feature art-historical works by Shiy De-jinn, Martin Wong, Tseng Kwong Chi, and Ku Fu-sheng alongside a collection of newer works mostly created after 2010 by artists such as Samson Young, Wu Tsang, and Ming Wong.[35]

The second iteration of the show, Spectrosynthesis II – Exposing Tolerance: LGBTQ Art in Southeast Asia, was held at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, Thailand in 2019.[36][37] It would feature over 50 artists such as Dinh Q. Lê, Danh Võ, and Ren Hang, with new commissions from Samak Kosem and Sornrapat Patharakorn, Balbir Krishan, David Medalla, Arin Rungjang, Anne Samat, Jakkai Siributr and Chov Theanly, with a greater emphasis of artists from Southeast Asia.[36][37]

Queer art and public space

[edit]Queer practices have a noted relationship to public space, from the wheatpasted activist posters of the 1980s and 1990s, to murals, public sculpture, memorials, and graffiti. From Jenny Holzer's Truism posters of the 1970s, to David Wojnarowicz's graffiti in the early 1980s, public space served as a politically significant venue for queer artists to display their work after years of suppression.[7]

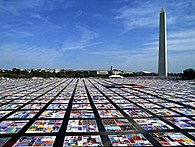

A significant example is the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt conceived by activist Cleve Jones. A continually-growing piece of public art, it allows people to commemorate loved ones lost to the disease through quilt squares. It was first displayed in 1987 during the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., covering an area larger than a football field.[7] Presently, people continue to add panels honouring names of lost friends, and the project has grown into various incarnations around the world, also winning a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, and raising $3 million for AIDS service organisations.[7]

Criticism

[edit]In attempting to conceive of queer art as a whole, one risks domesticating queer practices, smoothening over the radical nature and specificity of individual practices.[4] Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord further argue that with the new-found acceptance of the term "queer", it runs the risk of being recuperated as "little more than a lifestyle brand or niche market", with what was once rooted in radical politics now mainstream, thus removing its transformative potential.[7]

Lastly, limiting queer art too closely within the contexts of US and UK events excludes the varied practices of LGBT+ individuals beyond those geographies, as well as various conceptions of queerness across cultures. However, it is more than that and queer culture is widespread outside the assumed demographic.

References

[edit]- ^ Cooper, Emmanuel (1996). "Queer Spectacle". In Horne, Peter; Lewis, Reina (eds.). Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures. London: Routledge. pp. 13–28. ISBN 9780415124683.

- ^ "Queer Aesthetics". Tate. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Lord, Catherine; Meyer, Richard (2013). Art and Queer Culture. London; New York: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0714849355.

- ^ a b c d e f Getsy, David J. (2016). Queer: Documents of Contemporary Art. London; Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press. pp. 12–23. ISBN 978-0-85488-242-7.

- ^ a b Meyer, Richard (25 March 2019). "'Making art about queer sexuality is itself a kind of protest,' says Art & Queer Culture co-author Richard Meyer". Phaidon. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Clare, Barlow (2017). "Queer British Art 1861-1967". Tate. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ingram, Sarah (2018). "Queer Art". The Art Story. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b Pilcher, Alex (2017). A Queer Little History of Art. London: Tate. ISBN 978-1849765039.

- ^ Katz, Jonathan David (2010). "The Sexuality of Abstraction: Agnes Martin". In Lynne, Cooke; Kelly, Karen (eds.). Agnes Martin (Dia Foundation Series). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 135–159. ISBN 978-0300151053.

- ^ Meyer, Richard (February 2018). "Rauschenberg, with Affection". San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Germany's most famous gay rights activist: Rosa von Praunheim". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "Brief History of the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement in the U.S". University of Kentucky. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Nell Frizzell (June 28, 2013). "Feature: How the Stonewall riots started the LGBT rights movement". Pink News UK. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ "Stonewall riots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ Alleyne, Allyssia (21 September 2018). "The unsung photographer who chronicled 1970s lesbian life". CNN Style. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Link, Nathan (April 1988). "Concerns of Medical and Pediatric House Officers about Acquiring AIDS from their Patients". American Journal of Public Health: 445–459.

- ^ Emmerman, James (July 13, 2016). "After Orlando, the Iconic Silence = Death Image Is Back. Meet One of the Artists Who Created It". Slate.

- ^ Finkelstein, Avram (November 22, 2013). "Silence Equals Death Poster". New York Public Library.

- ^ "Fierce Pussy collection 1991-1994". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Haring, Keith, Götz Adriani, and Ralph Melcher. Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001. Print.

- ^ "Bio (archived)". The Keith Haring Foundation. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ^ Beyfus, Drusilla (26 Jun 2009). "Nan Goldin: unafraid of the dark". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Bracewell, Michael (14 November 1999). "Landmarks in the Ascent of Nan". The Independent. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ Dolan Hubbard (2004), "Langston Hughes: A Bibliographic Essay", in S. Tracy (2004), A Historical Guild to Langston Hughes, pp. 216-217, Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Burk, Tara (4 November 2015). "Queer Art: 1960s to the Present". Art History Teaching Resources. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Imperfect Moments: Mapplethorpe and Censorship Twenty Years Later" (PDF). Institute of Contemporary Art. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Meyer, Richard. "Glenn Ligon", in George E. Haggerty and Bonnie Zimmerman (eds), Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2. New York: Garland Publishing, 2000.

- ^ Vasiliki Neofotistos (2013). "Identity Politics". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Fritsch, Lena (2015). "Fen Ma + Liuming's Lunch I". Tate. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Wu Tsang - MacArthur Foundation". www.macfound.org. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ^ a b "WILDNESS". Electronic Arts Intermix. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Becoming an Image". Cassils. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "About". Cassils. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ "Spectrosynthesis - Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now". MoCA Taipei. 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Li, Alvin (15 December 2017). "Spectrosynthesis – Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now". Frieze. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "SPECTROSYNTHESIS II – Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia". Bangkok Art and Culture Centre. 22 November 2019. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b Rappolt, Mark (1 April 2020). "'Spectrosynthesis II – Exposure of Tolerance': LGBTQ in Southeast Asia at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre". ArtReview. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Lord, Catherine; Meyer, Richard (2013). Art and Queer Culture. New York: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0714849355.

- Getsy, David J. (2016). Queer: Documents of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262528672.

- Barlow, Clare (2017). Queer British Art: 1867-1967. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1849764520.

- Petit Dit Duhal, Quentin (2024). Art queer. Histoire et théorie des représentations LGBTQIA+, Joinville-le-Pont: Double ponctuation. ISBN 978-2-490855-61-2.

- Lewis, Reina; Horne, Peter (1996). Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415124689.

External links

[edit]- Queer Lives and Art by Tate (archived here)

- Queer Art by Sarah Ingram at The Art Story (archived here)

- Queer Art: 1960s to the Present by Tara Burk at Art History Teaching Resources (archived here)