Lambert-Sigisbert Adam

Lambert-Sigisbert Adam | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 October 1700 |

| Occupation | Sculptor |

Lambert-Sigisbert Adam (10 October 1700) was a French sculptor born in 1700 in Nancy. The eldest son of sculptor Jacob-Sigisbert Adam, he was known as Adam l’aîné ("the elder") to distinguish him from his two sculptor brothers Nicolas-Sébastien Adam, known as "Adam le jeune" ("the younger"), and François Gaspard Balthazar Adam. His sister Anne Adam married Thomas Michel, an undistinguished sculptor, and became the mother of famous sculptor Claude Michel, known as Clodion, who received his early training in the studio of his uncle Lambert-Sigisbert.

Life and career

[edit]In 1723 Adam received the Prix de Rome for study at the French Academy in Rome, which gave him a year scholarship in Rome, where he studied the works of the greats including Bernini and restored with much ability and late-Baroque freedom of interpretation a disparate group of fragmentary Roman sculptures to form a much-admired ensemble depicting Achilles and the Daughters of Lycomedes[1] that was purchased by the French Ambassador to the Holy See, Cardinal Melchior de Polignac, and was purchased from his estate by Frederick the Great for Potsdam. For the ensemble Adam reworked draped torsos of Apollo Musagetes type for the figures of Odysseus and Achilles. The head of Achilles was modeled on the antiquarian Philipp von Stosch, "a notorious spy, homoerotic fop and gem collector" [2] Adam was elected a member of the Roman artists' guild, the Accademia di San Luca in 1732.[3]

He was a pensionnaire of the academy in 1732 when he was one of the 16 sculptors and designers who submitted plans for the new Trevi Fountain. His design was unanimously accepted, and the processes by which the decision was reversed in favor of Nicola Salvi and his student Luigi Vanvitelli are not altogether clear. Roman reaction against a foreigner receiving the commission seems to have played a part, as they in the interim selected then rejected Florentine sculptor Alessandro Galilei,[4] and in a letter of 1741 Adam wrote that not having received prior permission to compete from the director of the French Academy, Charles Wleughels, he was recalled home to Paris in 1733 as punishment.[5]

Adam was thirty-seven when, on his election to the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, he exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1737 the model of the colossal group of The Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite that was afterwards (1740) cast in lead for the central fountain in the Bassin de Neptune at Versailles, and it made his reputation;[6] thereafter he found much employment in the decoration of the royal residences and in garden sculpture and fountains.[7] He also restored with much ability the 12 statues (Lycomedes) found in the so-called Villa of Marius in Rome, and was elected a member of the Academy of St Luke.[8]

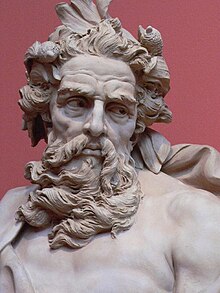

The dramatic realization of his figure of Neptune (illustration, below right) might lead one to expect that he would have been in demand for portrait busts; in fact, aside from the bust of the portraitist Hyacinthe Rigaud (1726), and two versions of the young Louis XV as Apollo,[9] none have been identified.

The work of the brothers Adam was too boldly Berniniesque in style to win the approval of the sculptors and critics of the following generation, that found its principal protagonists in Edmé Bouchardon and Jean-Baptiste Pigalle.[8] Pierre-Jean Mariette expressed the new taste in his severe criticism of the eldest of the Adam brothers:

- "This artist put into everything that he did a savage and barbarous taste and only rendered himself noted because one imagined that no one knew how to carve out marble as he did, and, to demonstrate it, he worked in such manner that everything formed hollows in his works. Thus do his figures have more the air of rockwork than of anything else at all."[10]

Two works

[edit]Two of his most important works were executed for Frederick the Great in Prussia. Mariette remarked of Adam's Hunting and Fishing, being sent to Frederick, that they "will not have lacked for admirers in a country where one does not yet completely know the value of beautiful and noble simplicity."[11]

The volume of a suite of etchings by various hands, after Adam's drawings, titled Recueil de sculptures antiques Grecques et Romaines[12] (Paris, 1754) represented a group of antiquities as broadly restored by Adam that he hoped to be able to sell. They remained in his possession and appear in the inventory of his atelier at No 4, rue Basse du Rempart, which was compiled at his death.[13]

Important works

[edit]Among his more important works are:

- The Virgin Appearing to St Andrew Corsini 1732, a relief for Pope Clement XII’s Cappella Corsini, San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome.

- Nymphs and Tritons

- Hunter with Lion in his Net, a relief for the chapel of St Adelaide

- The Seine and the Marne (1733–34) in stone for Antoine Le Pautre's grand cascade at the Château de Saint-Cloud[14]

- The Triumph of Neptune stilling the Waves 1737, reception piece for the academy (Musée du Louvre).

- Hunting and Fishing, marble groups for Sanssouci

- Mars embraced by Love

- The enthusiasm of Poetry

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the episode, part of the "prequel" to the Iliad, Odysseus by a ruse discovers young Achilles hidden among the daughters of Lycomedes.

- ^ Seymour Howard, "Some Eighteenth-Century 'Restored' Boxers" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56 (1993, pp. 238-255) p. 245. In the nineteenth century, after K. Levezow published the group (Levezow, Über die Familie des Lykomedes Berlin 1804), the head of Stosch was lost, Howard relates (1993:245:note 35).

- ^ His reception piece, a bust expressive of Sorrow, remains in the Accademia's collection.

- ^ "Art Now and then: Lambert-Sigisbert Adam". 22 November 2014.

- ^ A. Thirion, Les Adams et Clodion, (Paris) 1885:57, noted in Hereward Lester Cooke Jr., "The Documents Relating to the Fountain of Trevi" The Art Bulletin 38.3 (September 1956, pp. 149-173) p. 155. Adam's competition drawings appear not to have survived.

- ^ His brother Nicolas-Sébastien collaborated with him in the project.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Adam, Lambert Sigisbert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 172.

- ^ Terence Hodgkinson, "A Bust of Louis XV by Lambert Sigisbert Adam" The Burlington Magazine 94 No. 587 (February 1952), pp. 37-41, describes the terracotta bust (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) that was exhibited in a plaster cast at the Salon of 1741 and the marble exhibited in 1745 and retouched and dated 1749, in the collection of Baron Maurice de Rothschild.

- ^ Cet artiste mettoit dans tout ce qu'il faisoit un gout sauvage et barbare et ne se faisoit regarder que parcequ'on imaginoit que personne ne scavoit fouiller le marbre comme lui, et, pour le persuader, il faisoit en sorte que tout formait trous dans son ouvrages. Aussi ses figures ont-elles plutost l'air de rochers que de tout autre chose. (Mariette's Abecedario, quoted Hodgkinson 1952:40

- ^ "...n'auront pas manqué d'admirateurs dans un pays ou l'on ne connoit pas encore tout a fait le prix de la belle et noble simplicité" (Quoted by Hodginson 1952:40).

- ^ "Collection of Antique sculpture, Greek and Roman".

- ^ Hodgkinson 1952:38. For the changing taste in what was considered acceptable in restoring Roman sculpture after mid-century, see Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and Alessandro Albani.

- ^ The group was reproduced for the Château de Pomponne, doubtless in the nineteenth century (Peter Fusco, reviewing Allan Braham and Peter Smith, François Mansart in The Art Bulletin 58.2 (June 1976), p. 301.

External links

[edit]- Lambert-Sigisbert Adam in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website