Sudama

| Sudama | |

|---|---|

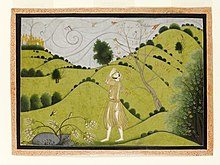

Sudama bows at the glimpse of Krishna's golden palace in Dvaraka. ca 1775-1790 painting. | |

| Texts | Puranas |

| Genealogy | |

| Spouse | Sushila[1] |

Sudama (Sanskrit: सुदामा, romanized: Sudāmā),[2] also known as Kuchela (Sanskrit: कुचेल, romanized: Kucela),[3] is a childhood friend of the Hindu deity Krishna. The story of his visit to Dvaraka to meet his friend is featured in the Bhagavata Purana.

In their legend, Sudama and Krishna study together as children at Sandipani's ashrama, believed to have been at Ujjain. Leading a life of abject poverty, Sudama's wife urges him to go to Krishna, and request his assistance. Carrying some handfuls of parched rice as a gift, Sudama visits his old friend at Dvaraka, who receives him with honour. After discerning Sudama's unrevealed poverty, Krishna creates various luxurious palaces for his friend where his hut had stood, which the former sees when he returns home.[4]

Legend

[edit]In one iteration of his legend, Sudama, along with Tulasi, are stated to have once resided in Krishna's own abode, Goloka, before a curse by Radha forced them to be born on earth.[5]

Accordingly, Sudama was born into a poor Brahmin family. He received his education as a pupil of Sandipani, who was also the preceptor of Krishna. While Sudama had only known poverty, his friend Krishna was from a royal family of Yaduvamsha lineage. Despite this difference in socioeconomic status, they were educated in the same way. According to one story, Krishna and Sudama were sent to the forest to get firewood for a havana. As they reached forest it started raining heavily and boys were stuck in forest for the whole night. Next Day early morning when the rain stopped guru and guru patni along with whole gurukul disciples went to the forest in search of two boys. [6] Despite this incident, their friendship did not waver. However, upon reaching adulthood, while Krishna became the ruler of Dvaraka, and became reputed for his deeds, Sudama remained a humble and impoverished villager.

The Bhagavata Purana narrates that eventually, Sudama's starving wife implored her husband to visit Krishna and tell him of his impoverishment, stating that as the refuge of his devotees and a patron of Brahmins, he would no doubt shower his old friend with great wealth. Despite his reluctance to seek help from Krishna, Sudama agreed, if only to see the deity, which would accrue punya. He asked his wife if there was anything he could bring his friend as a gift, and she was able to procure four handfuls of parched and beaten rice for him to take to Dvaraka. He entered the palace of Krishna, and found the deity seated on a couch with his favourite queen, Rukmini. Overjoyed at the sight of his old friend, Krishna made him sit on his own couch, and washed his feet, according to custom. He offered his friend a number of refreshments and smeared his body with pastes and perfumes. Rukmini herself attended on him, holding a whisk, to the astonishment of the women of the palace. Krishna and Sudama conversed about their boyhood days at the ashrama of Sandipani. Krishna recounted an incident when the duo were once tasked with bringing fuel from the forest during a great storm, wandering aimlessly as they held each other's hands, until their preceptor found them. The deity jovially asked his friend if he had brought any presents for him. Ashamed of what he had brought, Sudama did not respond. Being omniscient, Krishna declared that the grains of parched rice that had been brought to him were his favourite food, and swallowed one grain of it. Rukmini prevented him from having anymore, for the abundance of her consort's act overwhelmed the world. After spending the night in the palace, the Brahmin begun his journey back home, feeling small because he had been ashamed to ask for anything, but also content because he had obtained a darshana of the deity. He decided that Krishna had been merciful to deny him of wealth. Sudama returned to find that his humble hut had been transformed into several seven-storied palaces, filled with beautiful gardens and parks. He was welcomed by splendid musicians and singers. Delighted, his wife rushed to embrace him, looking like the goddess Lakshmi herself as she cried tears of joy. The flabbergasted Brahmin entered his house, finding that it resembled Svarga itself with its facilities and opulence. Sudama exulted in the generosity of the deity, for having smiled upon him during his time of misfortune. His wife and he enjoyed the worldly pleasures they had been blessed with without attachment, and grew even more devoted to Krishna.[7]

The generosity of Krishna and his friendship with Sudama is associated with the celebration of the festival of Akshaya Tritiya.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Khorana, Meena (1991). The Indian Subcontinent in Literature for Children and Young Adults: An Annotated Bibliography of English-language Books. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313254895.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (7 May 2018). "Sudama, Sudāmā: 13 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (19 August 2016). "Kucela, Kucelā, Ku-cela: 12 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (18 April 2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin UK. p. 1184. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- ^ Pintchman, Tracy (18 August 2005). Guests at God's Wedding: Celebrating Kartik among the Women of Benares. State University of New York Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7914-8256-8.

- ^ Narayan, Kirin (22 November 2016). Everyday Creativity: Singing Goddesses in the Himalayan Foothills. University of Chicago Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-226-40756-2.

- ^ Gita Press. Bhagavata Purana Gita Press. pp. 453–460.

- ^ Singh, K. V. (25 November 2015). Hindu Rites and Rituals: Origins and Meanings. Penguin UK. p. 39. ISBN 978-93-85890-04-8.