Krishnaism

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

Krishnaism is a term used in scholarly circles to describe large group of independent Hindu traditions—sampradayas related to Vaishnavism—that center on the devotion to Krishna as Svayam Bhagavan, Ishvara, Para Brahman, who is the source of all reality, not simply an avatar of Vishnu.[1][note 1] This is its difference from such Vaishnavite groupings as Sri Vaishnavism, Sadh Vaishnavism, Ramaism, Radhaism, Sitaism etc.[3] There is also a personal Krishnaism, that is devotion to Krishna outside of any tradition and community, as in the case of the saint-poet Meera Bai.[3] Leading scholars do not define Krishnaism as a suborder or offshoot of Vaishnavism, considering it at least a parallel and no less ancient current of Hinduism.[3][4]

The teachings of the Bhagavad Gita can be considered as the first Krishnaite system of theology. Krishnaism originated in the late centuries BCE from the followers of the heroic Vāsudeva Krishna, which amalgamated several centuries later, in the early centuries CE, with the worshipers of the "divine child" Bala Krishna and the Gopala-Krishna traditions of monotheistic Bhagavatism. These non-Vedic traditions in Mahabharata canon affiliate itself with ritualistic Vedism in order to become acceptable to the orthodox establishment. Krishnaism becomes associated with bhakti yoga and bhakti movement in the Medieval period.

The most remarkable Hindu scriptures for the Krishnaites became Bhagavad Gita, Harivamsa (appendix to the Mahabharata), Bhagavata Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana and Garga Samhita.

History

[edit]Overview

[edit]

Krishnaism originates in the first millennium BCE, as the theological system of the Bhagavad Gita,[3][5] initially focusing on the worship of the heroic Vāsudeva Krishna in the region of Mathura, the "divine child" Bala Krishna and Gopala-Krishna.[note 2] It is closely related to, and find its origin in, Bhagavatism.[7]

Krishnaism is a non-Vedic tradition in origin, but it further developed its appeal towards orthodox believers through the syncretism of these traditions with the Mahabharata epic. In particular Krishnaism incorporated more or less superficially the Vedic supreme deity Vishnu, who appears in the Rigveda.[note 3] Krishnaism further becomes associated with bhakti yoga in the Medieval period.

Ancient traditions. Northern India

[edit]Krishnaite theology and cult originate in the first millennium BCE in the Northern India. The theology of the Bhagavad Gita (around 3rd–2nd centuries BCE) was the first Krishnaite theological system, if, according to Friedhelm Hardy, to read Gita as itself and not in the light of the Mahabharata frame with Vishnu-focussed doctrine.[3] There is no concept of the avatara, which was introduced only in 4th or 5th century CE. There is Krishna as an eternal himself, unmanifest Vishnu.[3] As Krishna says:

Whenever dharma suffering a decline, I emit myself [into the physical world]

— Bhagavad Gita 4.7[3]

Early Krishnaism already flourished several centuries BCE with the cult of the heroic Vāsudeva Krishna in and around the region of Mathura,[3][12][13][14] which, several centuries later, was amalgamated with the cult of the "divine child" Bala Krishna and the Gopala traditions.[12][15] While Vishnu is attested already in the Rigveda as a minor deity, the development of Krishnaism appears to take place via the worship of Vasudeva in the final centuries BCE. But, in accordance with Dandekar, the "Vasudevism" marks the beginning of Vaishnavism in whole. In other words, Krishnaism, according to Dandekar, is not an offshoot of Vaishnavism, but, on the contrary, the cult of Vishnu and his avatars is the later transformation of Krishnaism-Bhagavatism.[note 4] This earliest phase was established in the time of Pāṇini (4th century BCE) who, in his Astadhyayi, explained the word vasudevaka as a bhakta (devotee) of Vasudeva.[16][17][18][19] At that time, Vāsudeva was already considered as a demi-God, as he appears in Pāṇini's writings in conjunction with Arjuna as an object of worship, since Pāṇini explains that a vāsudevaka is a devotee (bhakta) of Vāsudeva.[17][20][21]

A branch which flourished with the decline of Vedism was centred on Krishna, the deified tribal hero and religious leader of the Yadavas.[22] Worship of Krishna, the deified tribal hero and religious leader of the Yadavas, took denominational form as the Pancaratra and earlier as Bhagavata religions. This tradition has at a later stage merged with the tradition of Narayana.[7]

The character of Gopala Krishna is often considered to be non-Vedic.[23]

By the time of its incorporation into the Mahabharata canon during the early centuries CE, Krishnaism began to affiliate itself with Vedism in order to become acceptable to orthodoxy, in particular aligning itself with Rigvedic Vishnu.[6] At this stage that Vishnu of the Rig Veda was assimilated into Krishnaism and became the equivalent of the Supreme God.[22] The appearance of Krishna as one of the Avatars of Vishnu dates to the period of the Sanskrit epics in the early centuries CE. The Bhagavad Gita was incorporated into the Mahabharata as a key text for Krishnaism.[24]

Early medieval traditions. Southern and Eastern India

[edit]

By the Early Middle Ages, Krishnaism had risen to a major current of Vaishnavism.[6]

According to Friedhelm Hardy,[note 5] there is evidence of early "southern Krishnaism," despite the tendency to allocate the Krishna-traditions to the Northern traditions.[25] South Indian texts show close parallel with the Sanskrit traditions of Krishna and his gopi companions, so ubiquitous in later North Indian text and imagery.[27] Early writings in Dravidian culture such as Manimekalai and the Cilappatikaram present Krishna, his brother, and favourite female companions in the similar terms.[27] Hardy argues that the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana is essentially a Sanskrit "translation" of the bhakti of the Tamil alvars.[28]

Devotion to southern Indian Mal (Thirumal) may be an early form of Krishnaism, since Mal appears as a divine figure, largely like Krishna with some elements of Vishnu.[29] The alvars, whose name can be translated "sages" or "saints", were devotees of Mal. Their poems show a pronounced orientation to the Vaishnava, and often Krishna, side of Mal. But they do not make the distinction between Krishna and Vishnu on the basis of the concept of the avatars.[29] Yet, according to Hardy the term "Mayonism" should be used instead of "Krishnaism" when referring to Mal or Mayon.[25]

At the same ages, in East India, the Jagannathism (a.k.a. Odia Vaishnavism) was origined as the cult of the god Jagannath (lit. ''Lord of the Universe'')—an abstract form of Krishna.[30] Jagannathism is a regional, previously state, temple-centered version of Krishnaism,[3][31] where Lord Jagannath is understood as a principal god, Purushottama and Para Brahman, but can also be regarded as a non-sectarian syncretic Vaishnavite and pan-Hindu cult.[32] According to the Vishnudharma Purana (c. 4th century), Krishna is woshipped in the form of Purushottama in Odra (Odisha).[33] The Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha is particularly significant within the tradition and one of the major pilgrimage destinations for Hindus since about 800 CE, later became a centre of attraction for a number of both Krishnaite and other Vaishnava acharyas,[34] and a place where for the first time the famous poem Gita Govinda was introduced into the liturgy.[35]

Vaishnavism in the 8th century came into contact with the Advaita doctrine of Adi Shankara. Vasudeva has been interpreted by Adi Shankara, using the earlier Vishnu Purana as a support, as meaning the "supreme self" or Vishnu, dwelling everywhere and in all things.[36]

At this period emerged one of key texts for Krishnaites, the Bhagavata Purana, that promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna.[37] In it one reads:

Kṛṣņa is Bhagavān himself

— Bhagavata Purana 1.3.28[3]

Another notable bouquet of glory of Krishna was the poems in Sanskrit, possibly by Bilvamangala from Kerala, the Balagopala Stuti ("The Childhood of Krishna")[38] and the Shree Krishna Karnamrutam (also called Lilasuka, "Playful parrot"), that later became a favorite text of the Bengali acharya Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.[3][39]

High and late medieval traditions

[edit]

This is the most important period, it was at this time that Krishnaism acquired the form in which its traditions exist to nowadays. The bhakti movement of the high and later Middle Ages Hinduism emerges in the 9th or 10th century, and is based (its Krishnaite form) on the Bhagavata Purana, Narada Bhakti Sutra, and other scriptures. In North and East India, Krishnaism gave rise to various Medieval movements.[40] Early Bhakti Krishnaite pioneers include a Telugu-origin philosopher Nimbarkacharya (12th or 13th century CE), a founder of the first Bhakti-era Krishnaite Nimbarka Sampradaya (a.k.a. Kumara sampradaya),[41] and his an Odisha-born friend, poet Jayadeva, author of Gita Govinda.[42][43][44] Both promoted Radha Krishna to be the supreme lord while the ten incarnations are his forms.[41][45] Nimbarka more than any other acharyas gave Radha a place as a deity.[46]

Since 15th century in Bengal and Assam flourished Tantric variety of Krishnaism—Vaishnava-Sahajiya linked to the Bengali poet Chandidas, as well as related to it Bauls—where Krishna is the inner divine aspect of man and Radha is the aspect of woman.[47] Chandidas' Shrikrishna Kirtana, a poem on Krishna and Radha, depicts them as divine couple, but in human love.[48]

The other 15th–16th centuries Bhakti poet-sants – Vidyapati, Meera Bai, Surdas, Swami Haridas, as well as Narsinh Mehta (1350–1450), who preceded all of them, also wrote about Radha and Krishna love.[49]

The most emerged Krishnaite guru-acharyas of 15th–16th centuries were Vallabhacharya in Braj, Sankardev in Assam, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in Bengal. They developed their own schools, namely Pushtimarg sampradaya of Vallabha,[50] Gaudiya Vaishnavism, a.k.a. Chaitanya Sampradaya (rather, Chaitanya was an inspirator with no formal successors),[51] with Krishna and his chief consort and shakti Radha as the supreme god, and Ekasarana Dharma tradition of Sankardev who worship only Krishna, that started under the influence of the Odia cult of Jagannath.[46][52][53]

In the Western Indian state of Maharashtra, saint poets of the Warkari tradition such as Dnyaneshwar, Namdev, Janabai, Eknath, and Tukaram promoted the worship of Vithoba, a local form of Krishna, from the late of the 13th century until the late 18th century.[54] Before the Warkari sampradaya, Krishna devotion (Pancha-Krishna, i.e. five Krishnas) became well established in Maharashtra due to the rise of Mahanubhava Panth founded by the 13th-century Gujarati acharya Chakradhara.[55] Both schools, Warkari and Mahanubhava, venerated Krishna and his wife Rukmini (Rakhumai).[3]

In 16th century in Mathura region, offshoot of Krishnaism is established as Radha Vallabha Sampradaya by the Braj-language poet-sant Hith Harivansh Mahaprabhu and who emphasized devotion to Radha as the ultimate supreme deity.[56]

Modern times

[edit]

The Pranami Sampradaya (Pranami Panth) emerged in the 17th century in Gujarat, based on the Krishna-focussed syncretist Hindu-Islamic teachings of a Sindh-born Devchandra Maharaj (1581–1655) and his famous successor, Mahamati Prannath (1618–1694).[57]

During the 18th century at Kolkata existed the Sakhībhāvakas community, whose members ware female dress in order to identify themselves with the gopis, companions of Radha.[3]

In non-Indo-Aryan Manipur region, after a short period of Ramaism penetration, Gaudiya Vaishnavism spread, especially from beginning the second quarter of the 18th century (Manipuri Vaishnavism, the lineage of Natottama Thakura).[58]

In the 1890s in Bengal, Mahanam Sampradaya emerged as an offshoot of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. Prabhu Jagadbandhu was considered a new incarnation of Krishna, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Nityananda by his followers.[59]

At the beginning of the 20th century the first attempts at a Krishnaite mission in the West began. A pioneer of American mission has become Baba Premananda Bharati (1858–1914) from the circle of mentioned Prabhu Jagadbandhu.[60] Baba Bharati founded in 1902 the short-lived "Krishna Samaj" society in New York City and built a temple in Los Angeles.[61][62] He was an author of the first full-length treatment of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in English Sree Krishna—the Lord of Love (New York, 1904);[63] the author sent the book to Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, who was intrigued and used text for composition his notable A Letter to a Hindu.[64] Baba Bharati's followers later formed several organisations in US, including now defunct the Order of Living Service and the AUM Temple of Universal Truth.[62]

Within Gaudiya Vaishnavism in 20th century was also established the reform Gaudiya Math and its largest worldwide successor, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (a.k.a. Hare Krishna Movement), formed in New York by acharya A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.[3]

There is the number of neo-Hindu Krishnaite organisations only partially related to traditional sampradayas, such as Jagadguru Kripalu Parishat, Jagadguru Kripaluji Yog, and westernezed Science of Identity Foundation.

Krishnaite authors continue to create major theological and poetic works. For instance, the Shri Radhacharita Mahakavyam—the 1980s epic poem of Kalika Prasad Shukla that focuses on devotion to Krishna as the universal lover—"one of the rare, high-quality works in Sanskrit in the twentieth century."[65]

List of living Krishnaite traditions

[edit]Krishnaism is mainly subdivided into three categories[66] –

- Exclusive worship of Krishna as supreme god or as incarnation of Vishnu.

- Exclusive worship of Radha as original shakti of Krishna or Vishnu.

- Worship of Radha Krishna conjointly.

|

Radha Krishna as the Supreme[3]

|

Krishna with Rukmini as the Supreme[3]

|

Krishna as the Supreme

|

Remark: Radha Vallabh Sampradaya is conditionally Krishnaite, representing such current as Radhaism, due to the worship of Radha as the supreme deity, where Krishna is only her most intimate servant.[3][68]

Beliefs

[edit]

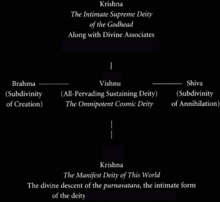

Krishnaism and Vaishnavism

[edit]The term "Krishnaism" has been used to describe the schools, related to Vaishnavism, but focused on Krishna, while "Vishnuism/Vaishnavism" may be used for traditions focusing on Vishnu in which Krishna is an avatar, rather than a transcended Supreme Being.[69][70] At the same time, Friedhelm Hardy does not at all define Krishnaism as a suborder or offshoot of Vaishnavism, considering it a parallel and no less ancient current of Hinduism.[3] And, in accordance with Dandekar, the "Vasudevism" (the Vasudeva cult) is the beginning stage of Vaishnavism, hence, Krishnaism was basis for later Vaishnavism.[note 6] Vishnuism believes in Vishnu as the supreme being, manifested himself as Krishna, thence Krishnaites assert Krishna to be Svayam Bhagavan (lit. 'Sanskrit: 'The Fortunate and Blessed One Himself'), Ishvara, the Para Brahman in human form,[71][note 7][note 8][note 9][75] that manifested himself as Vishnu. As such Krishnaism is believed to be one of the early attempts to make philosophical Hinduism appealing to the masses.[76] In common language the term Krishnaism is not often used, as many prefer a wider term "Vaishnavism", which appeared to relate to Vishnu, more specifically as Vishnu-ism.

Krishnaism is often also called Bhagavatism, after the Bhagavata Purana which asserts that Krishna is "Bhagavan Himself," and subordinates to itself all other forms: Vishnu, Narayana, Purusha, Ishvara, Hari, Vāsudeva, Janardana, and so on.[note 10]

Krishna

[edit]Vaishnavism is a monotheistic religion, centered on the devotion of Vishnu and his avatars. It is sometimes described as a "polymorphic monotheism", since there are many forms of one original deity, with Vishnu taking many forms. In Krishnaism this deity is Krishna—often together with his consort Radha as deity Radha Krishna[78]—sometimes referred as intimate deity — as compared with the numerous four-armed forms of Narayana or Vishnu.[79]

Krishna is also worshiped across many other traditions of Hinduism. Krishna is often described as having the appearance of a dark-skinned person and is depicted as a young cowherd boy playing a flute or as a youthful prince giving philosophical direction and guidance, as in the Bhagavad Gita.[80]

Krishna and the stories associated with him appear across a broad spectrum of different Hindu philosophical and theological traditions, where it is believed that God appears to his devoted worshippers in many different forms, depending on their particular desires. These forms include the different avataras of Krishna described in traditional Vaishnavite texts, but they are not limited to these. Indeed, it is said that the different expansions of the Svayam bhagavan are uncountable and they cannot be fully described in the finite scriptures of any one religious community.[81][82] Many of the Hindu scriptures sometimes differ in details reflecting the concerns of a particular tradition, while some core features of the view on Krishna are shared by all.[83]

Common scriptures

[edit]

The most remarkable Hindu scriptures for the Krishnaites became Bhagavad Gita,[3][84][85] Harivamsa (appendix to the Mahabharata),[86][87] and Bhagavata Purana (especially the 10th Canto).[88][89][90][91] While every tradition of Krishnaism has its own canon, in all Krishna is accepted as a teacher of the path in the scriptures Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavata Purana—"the Bible of Krishnaism".[92][93][94][95][note 11]

As Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita, establishing the basis of Krishnaism himself:

- "And of all yogins, he who full of faith worships Me, with his inner self abiding in Me, him, I hold to be the most attuned (to me in Yoga)."[97]

- "After attaining Me, the great souls do not incur rebirth in this miserable transitory world, because they have attained the highest perfection."[98]

In Gaudiya Vaishnava, Vallabha Sampradaya, Nimbarka sampradaya and the old Bhagavat school, Krishna is believed to be fully represented in his original form in the Bhagavata Purana, that at the end of the list of avataras concludes with the following assertion:[99]

All of the above-mentioned incarnations are either plenary portions or portions of the plenary portions of the Lord, but Sri Krishna is the original Personality of Godhead (Svayam Bhagavan).[100]

Not all commentators on the Bhagavata Purana stress this verse, however a majority of Krishna-centered and contemporary commentaries highlight this verse as a significant statement.[101] Jiva Goswami has called it Paribhasa-sutra, the "thesis statement" upon which the entire book or even theology is based.[102][103]

In another place of the Bhagavata Purana (10.83.5–43) those who are named as wives of Krishna all explain to Uraupadi how the 'Lord himself' (Svayam Bhagavan, Bhagavata Purana 10.83.7) came to marry them. As they relate these episodes, several of the wives speak of themselves as Krishna's devotees.[104] In the tenth canto the Bhagavata Purana describes svayam bhagavans Krishna's childhood pastimes as that of a much-loved child raised by cowherds in Vrindavan, near to the Yamuna River. The young Krishna enjoys numerous pleasures, such as thieving balls of butter or playing in the forest with his cowherd friends. He also endures episodes of carefree bravery protecting the town from demons. More importantly, however, he steals the hearts of the cowherd girls (Gopis). Through his magical ways, he multiplies himself to give each the attention needed to allow her to be so much in love with Krishna that she feels at one with him and only desires to serve him. This love, represented by the grief they feel when Krishna is called away on a heroic mission and their intense longing for him, is presented as models of the way of extreme devotion (bhakti) to the Supreme Lord.[105]

Edwin F. Bryant describes the synthesis of ideas in Bhagavata Purana 10th Book as:

The tenth book promotes Krishna as the highest absolute personal aspect of godhead — the personality behind the term Ishvara and the ultimate aspect of Brahman.[106]

- Other common scriptures

- Brahma Vaivarta Purana is one of major Puranas, that centers around Krishna and Radha, identifying Krishna as the Supreme Being and asserting that all deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, Ganesha are incarnations of Him;[3]

- Gita Govinda is a poem of Jayadeva that firstly considers the cult Radha Krishna,[42][43][3][44] where Krishna speaks to Radha:

O woman with desire, place on this patch of flower-strewn floor your lotus foot,

And let your foot through beauty win,

To me who am the Lord of All, O be attached, now always yours.

O follow me, my little Radha.— Jayadeva, Gita Govinda[42]

- Narayaniyam is Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri's poem as a summary of the Bhagavata Purana.

- Padma Purana deals a big part with Krishnaism, which is mostly the same as the theme of Brahma Vaivarta Purana, mainly Krishna's greatness begins at the later half of the fifth Canto.[107]

- Garga Samhita is a detailed Vaishnavite scripture written by sage Garga on the life events of Radha Krishna. It is the earliest text available which associates the festival of Holi with them.[108][109][110]

Philosophy and theology

[edit]

A wide range of theological and philosophical ideas are presented through Krishna in Krishnaite texts. The teachings of the Bhagavad Gita can be considered as the first Krishnaite system of theology in terms of Bhakti yoga.[3]

The Bhagavata Purana synthesizes an Vedanta, Samkhya, and devotionalized Yoga praxis framework for Krishna but one that proceeds through loving devotion to Krishna.[106]

Bhedabheda became a main kind of Krishnaite philosophy, which teaches that the individual self is both different and not different from the ultimate reality. It predates the positions of nondualism (namely Vishishtadvaita of Ramanuja) and dualism (Dvaita of Madhvacharya). Among medieval Bhedabheda thinkers are Nimbarkacharya, who founded the Dvaitadvaita school),[112] as well as Jiva Goswami, a saint from Gaudiya Vaishnavism, described Krishna theology in terms of Achintya Bheda Abheda philosophical school.[113]

Krishna theology is presented in a pure monism (Advaita Vedanta framework by Vallabhacharya, who was the founder of Shuddhadvaita school of philosophy.[114]

The acharya-founders of the remaining Krishnaite sampradayas did not create new schools of philosophy, following the old ones or nor attaching importance to philosophical speculations. Thus, the philosophical base of the Warkari and Mahanubhava traditions is the Dvaitin, and Ekasarana Dharma is the Advaitin. And the Radha-vallabha Sampradaya prefers to remain unaffiliation with any philosophical positions and declines to produce theological and philosophical commentaries, basing on pure bhakti, divine love.[115]

Practices

[edit]Maha-mantra

[edit]

A mantra is a sacred utterance. The most basic and known it among the Krishnaites—Mahā-mantra ("Great Mantra")—is a 16-word mantra in Sanskrit which is mentioned in the Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa Upaniṣad:[116][117]

Hare Rāma Hare Rāma

Rāma Rāma Hare Hare

Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa

Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare— Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa Upaniṣad

Its variety within Gaudiya Vaishnavism looks as:

Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa

Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare

Hare Rāma Hare Rāma

Rāma Rāma Hare Hare

The Maha-mantra Radhe Krishna of Nimbarka Sampradaya is as follows:

Rādhe Kṛṣṇa Rādhe Kṛṣṇa

Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Rādhe Rādhe

Rādhe Shyām Rādhe Shyām

Shyām Shyām Rādhe Rādhe

Kirtan

[edit]

A characteristic part of spiritual practice, in almost all traditions of Krishnaism, is a kirtan, a collective musical performance with chanting of the glories of God.

The Marathi Varkari saint Namdev used the kirtan form of singing to praise the glory of Vithoba (Krishna). Marathi kirtan is typically performed by one or two main performers, called "kirtankar", accompanied by harmonium and tabla. It involves singing, acting, dancing, and story-telling. The naradiya kirtan popular in Maharashtra is performed by a single kirtankar, and contains the poetry of saints of Maharashtra such as Dnyaneshwar, Eknath, Namdev and Tukaram.[118]

In Vrindavan of Braj region, a kirtan accords the Hindustani classical music. Vallabha launched a kirtan singing devotional movement around the stories of baby Krishna and his early childhood.[119] And "Samaj-Gayan" is the Radha-vallabha Sampradaya's collective style of hymn singing by the Hindustani classical forms "dhrupad" and "dhamar".[120]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu popularized adolescent the love between Radha and Krishna based extatic public san-kirtan in Bengal, with Hare Krishna mantra other songs and dances, wherein the love between Radha and Krishna was symbolized as the love between one's soul and God.[119]

Sankardev in Assam helped establish satras (temples and monasteries) with kirtan-ghar (also called namghar), for singing and dramatic performance of Krishna-related theology.[121]

Holy places

[edit]

The three main pilgrimage sites related to Krishna circuit are "48 kos parikrama of Kurukshetra" in Haryana state, "Vraja Parikrama" at Mathura in Uttar Pradesh and "Dwarka Parkarma" (Dwarkadish yatra) at Dwarkadhish Temple in Gujarat.

Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh, is often considered to be a holy place by majority of traditions of Krishnaism. It's a center of Krishna worship and the area includes places like Govardhana and Gokula associated with Krishna from time immemorial. Many millions of bhaktas or devotees of Krishna visit these places of pilgrimage every year and participate in a number of festivals that relate to the scenes from Krishna's life on Earth.[96][123][124]

On the other hand, Goloka is considered the eternal abode of Krishna, Svayam Bhagavan according to some Krishnaite schools, including Gaudiya Vaishnavism. The scriptural basis for this is taken in Brahma Samhita and Bhagavata Purana.[125]

The Dwarkadhish Temple (Dwarka, Jujarat) and the Jagannath Temple (Puri, Odisha) are particularly significant in Krishnaism, and are regarded have been two of the four major pilgrimage destinations for most Hindus as the Char Dham pilgrimage sites.[34]

Demography

[edit]

There are adherents of Krishnaism in all strata of Indian society, but a tendency has been revealed, for example, Bengal Gaudiya Vaishnavas belong to the lower middle castes, while the upper castes as well as lowest castes and tribes are Shaktas.[126]

Krishnaism has a limited following outside of India, especially associated with 1960s counter-culture, including a number of celebrity followers, such as George Harrison, due to its promulgation throughout the world by the founder-acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.[127][128][129] The first Hindu member of the United States Congress Tulsi Gabbard is follower of the Krishnaite organisation Science of Identity Foundation.[130][131]

Krishnaism and Christianity

[edit]Debaters have often alleged a number of parallels between Krishnaism and Christianity, originating with Kersey Graves' The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors claiming 346 parallels between Krishna and Jesus,[132] theorizing that Christianity emerged as a result of an import of pagan concepts upon Judaism. Some 19th- to early 20th-century scholars writing on Jesus Christ in comparative mythology (John M. Robertson, Christianity and Mythology, 1910) even sought to derive both traditions from a common predecessor religion.[note 12]

Gallery of key Krishnaite temples

[edit]-

Dwarkadhish Temple, Dwarka, Gujarat

-

Jagannath Temple, Puri, Odisha

-

Govind Dev Ji Temple, Jaipur, Rajasthan

-

Vithoba Temple, Maharashtra

-

Radha Damodar Temple, Junagadh, Gujarat

-

Guruvayur Temple, Guruvayur, Kerala

-

Udupi Sri Krishna Matha, Udupi, Karnataka

-

Ukhra Mahanta Asthal, West Bengal

-

Rasmancha, Bishnupur, West Bengal

-

Lalji Temple, Kalna

-

Ningthoukhong Gopinath Temple, Manipur

-

Yogapith Temple, Mayapur

-

Gour Nitai Temple, Gaudiya Math, Kolkata

-

Madhupur Satra, West Bengal

-

Barpeta Satra, Assam

-

Athkheliya Namghar, Golaghat, Assam

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The term Kṛṣṇaism, then, can be used to summarize a large group of independent systems of beliefs and devotion that developed over more than two thousand years ..."[2]

- ^ "Present day Krishna worship is an amalgam of various elements. According to historical testimonies Krishna-Vāsudeva worship already flourished in and around Mathura several centuries before Christ. A second important element is the cult of Krishna Govinda. Still later is the worship of Bala-Krishna, the Divine Child Krishna — a quite prominent feature of modern Krishnaism. The last element seems to have been Krishna Gopijanavallabha, Krishna the lover of the Gopis, among whom Radha occupies a special position. In some books Krishna is presented as the founder and first teacher of the Bhagavata religion."[6]

- ^ "Non-Vedic in origin and development, Kṛṣṇaism now sought affiliation with Vedism so that it could become acceptable to the still not inconsiderable orthodox elements among the people. That is how Viṣṇu of the Ṛgveda came to be assimilated—more or less superficially—into Kṛṣṇaism."[8]

- ^ "The origin of Vaiṣṇavism as a theistic sect can by no means be traced back to the Ṛgvedic god Viṣṇu. In fact, Vaiṣṇavism is in no sense Vedic in origin. (...) Strangely, the available evidence shows that the worship of Vāsudeva, and not that of Viṣṇu, marks the beginning of what we today understand by Vaiṣṇavism. This Vāsudevism, which represents the earliest known phase of Vaiṣṇavism, must already have become stabilized in the days of Pāṇini (sixth to fifth centuries bce)."[4]

- ^ Friedhelm Hardy in his Viraha-bhakti analyses the history of Krishnaism, specifically all pre-11th-century sources starting with the stories of Krishna and the gopi, and Mayon mysticism of the Vaishnava Tamil saints, Sangam Tamil literature and Alvars' Krishna-centered devotion in the rasa of the emotional union and the dating and history of the Bhagavata Purana.[25][26]

- ^ "The origin of Vaiṣṇavism as a theistic sect can by no means be traced back to the Ṛgvedic god Viṣṇu. In fact, Vaiṣṇavism is in no sense Vedic in origin. (...) Strangely, the available evidence shows that the worship of Vāsudeva, and not that of Viṣṇu, marks the beginning of what we today understand by Vaiṣṇavism. This Vāsudevism, which represents the earliest known phase of Vaiṣṇavism, must already have become stabilized in the days of Pāṇini (sixth to fifth centuries bce)."[4]

- ^ "(...) After attaining to fame eternal, he again took up his real nature as Brahman. The most important among Visnu's avataras is undoubtedly Krsna, the black one, also called Syama. For his worshippers he is not an avatara in the usual sense, but Svayam Bhagavan, the Lord himself."[72]

- ^ "On the touch-stone of this definition of the final and positive characteristic of Sri Krsna as the Highest Divinity as Svayam-rupa Bhagavan."[73]

- ^ "The Bengal School identifies the Bhagavat with Krishna depicted in the Shrimad-Bhagavata and presents him as its highest personal God."[74]

- ^ "It becomes clear that the personality of Bhagvan Krishna subordinates to itself the titles and identities of Vishnu, Narayana, Purusha, Ishvara, Hari, Vasudeva, Janardana etc. The pervasive theme, then, of the Bhagavata Puran is the identification of Bhagavan with Krishna."[77]

- ^ "..Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavata Purana, certainly the most popular religious books in the whole of India. Not only was Krsnaism influenced by the identification of Krsna with Vishnu, but also Vaishnavism as a whole was partly transformed and reinvented in the light of the popular and powerful Krishna religion. Bhagavatism may have brought an element of cosmic religion into Krishna worship; Krishna has certainly brought a strongly human element into Bhagavatism. ... The center of Krishna-worship has been for a long time Brajbhumi, the district of Mathura that embraces also Vrindavana, Govardhana, and Gokula, associated with Krishna from the time immemorial. Many millions of Krishna bhaktas visit these places ever year and participate in the numerous festivals that reenact scenes from Krshnas life on Earth."[96]

- ^ "John M. Robertson wrote a learned treatise entitled "Christ and Krishna", and in that work he argued that there was no direct contact between Krishnaism and Christianity; but that both sects were derived from an earlier common source."[133]

References

[edit]- ^ Mullick 1898; Hein 1986, pp. 296–317; Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392; Flood 1996, p. 117; Matchett 2001; Bryant 2007, p. 381.

- ^ Hardy 1987, p. 392.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392.

- ^ a b c Dandekar 1987, p. 9499.

- ^ See also: Stewart 2010

- ^ a b c Klostermaier 2005, p. 206.

- ^ a b Welbon 1987.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea, ed. (1987). The Encyclopedia of religion. Vol. 15. MacMillan. p. 170.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence, 2016.

- ^ Srinivasan, Doris (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Brill. p. 215. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8.

- ^ a b Basham 1968, pp. 667–670.

- ^ Hudson 1983.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 4.

- ^ Hein 1986, pp. 296–317.

- ^ Goswami 1956.

- ^ a b Flood 1996, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. Brill Academic. pp. 211–220, 236. ISBN 90-04-10758-4.

- ^ Christopher Austin (2018). Diana Dimitrova and Tatiana Oranskaia (ed.). Divinizing in South Asian Traditions. Taylor & Francis. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-1-351-12360-0.

- ^ Malpan, Varghese (1992). A Comparative Study of the Bhagavad-gītā and the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola on the Process of Spiritual Liberation. Gregorian Biblical BookShop. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-88-7652-648-0.

- ^ "The affix vun comes in the sense of "this is his object of veneration" after the words 'Vâsudeva' and 'Arjuna'", giving Vâsudevaka and Arjunaka. Source: Aṣṭādhyāyī 2.0 Panini 4-3-98

- ^ a b "Vaishnava". philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ Ramkrishna Gopal Bhandarkar, Ramchandra Narayan Dandekar (1976). Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar as an Indologist: A Symposium. India: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 38–40.

- ^ G. Widengren (1997). Historia Religionum: Handbook for the History of Religions – Religions of the Present. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 270. ISBN 90-04-02598-7.

- ^ a b c Hardy 1981.

- ^ "Book review: Friedhelm Hardy, Viraha Bhakti: The Early History of Krishna Devotion in South India. Oxford University Press, Nagaswamy 23 (4): 443 — Indian Economic & Social History Review". ier.sagepub.com. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ a b Monius, Anne E. "Dance Before Doom. Krishna In The Non-Hindu Literature of Early Medieval South India" in Beck 2005, pp. 139–149

- ^ Norman Cutler (1987) Songs of Experience: The Poetics of Tamil Devotion, p. 13

- ^ a b "Devotion to Mal (Mayon)". philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ a b Mukherjee 1981; Eschmann, Kulke & Tripathi 1978; Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392; Rajaguru 1992; Guy 1992, pp. 213–230; Starza 1993; Kulke & Schnepel 2001; Miśra 2005, chapter 9. Jagannāthism.

- ^ Mukherjee 1981.

- ^ Miśra 2005, p. 97, chapter 9. Jagannāthism.

- ^ Starza 1993, p. 76.

- ^ a b Bryant 2007, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Datta 1988, pp. 1419–1420.

- ^ Ganguli translation of Mahabharata, Chapter 148

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Archer 2004, 5.3. Later Poetry.

- ^ Stewart 2010, p. 303.

- ^ Lorenzen 1995.

- ^ a b c Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392; Clémentin-Ojha 1990, pp. 327–376; Ramnarace 2014; Vemsani 2016, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Archer 2004, 5.2. The Gita Govinda.

- ^ a b Love Song of the Dark Lord: Jayadeva's Gītagovinda 1977.

- ^ a b Datta 1988, pp. 1414–1423.

- ^ "Nimbarka". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ a b Datta 1988, p. 1415.

- ^ a b Basu 1932; Dasgupta 1962; Das 1988; Hine 2003; Hayes 2005, pp. 19–32; Sardella & Wong 2020, part 2.

- ^ Stewart 1986, pp. 152–154; Dalal 2010, p. 385, Shrikrishna Kirtana.

- ^ Archer 2004, 5.3. Later Poetry; Hardy 1987, pp. 387–392; Hawley 2005; Rosenstein 1997; Schomer & McLeod 1987; Sivaramkrishna & Roy 1996.

- ^ a b White & Redington 1990, pp. 373–374; Redington 1992, pp. 287–294; Patel 2005, pp. 127–136.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1925; De 1960; Chakravarti 1985; Elkman 1986; Rosen 1994; Chatterjee 1995, pp. 1–14; Gupta 2007; Stewart 2010; Gupta 2014.

- ^ a b Sarma 1966; Murthy 1973; Medhi 1978; Neog 1980; Bryant 2007, chapter 6.

- ^ Dalal 2010, pp. 373–374.

- ^ a b Iwao 1988, pp. 183–197; Glushkova 2000, pp. 47–58.

- ^ a b Feldhaus 1983; Dalal 2010, Mahanubhava.

- ^ a b White 1977; Snell 1991; Brzezinski 1992, pp. 472–497; Rosenstein 1998, pp. 5–18; Beck 2005, pp. 65–90.

- ^ a b Khan 2002; Dalal 2010, Pranami Panth; Toffin 2012, pp. 249–254.

- ^ Singh 2004, pp. 125–132.

- ^ Carney 2020, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Carney 2020, pp. 135–136, 140–143.

- ^ Carney 2020, pp. 152.

- ^ a b Jones & Ryan 2007, pp. 79–80, Baba Premanand Bharati.

- ^ Carney 2020, p. 140.

- ^ Carney 2020, p. 154.

- ^ Dalal 2010, p. 384, Shri Radhacharita Mahakavyam.

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1885). The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: Commercial, Industrial and Scientific, Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures (3rd ed.). London: B. Quaritch. p. 62.

- ^ Carney 2020, pp. 140–143.

- ^ Beck 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Matchett 2001.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 309.

- ^ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (1997). The Charles Strong Trust Lectures, 1972–1984. Crotty, Robert B. Brill. p. 109. ISBN 978-90-04-07863-5.

- ^ Indian Philosophy & Culture. Vol. 20. Institute of Oriental Philosophy (Vrindāvan, India), Institute of Oriental Philosophy, Vaishnava Research Institute, contributors. The Institute. 1975. p. 148.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ De 1960, p. 113.

- ^ McDaniel 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Wilson, Bill; McDowell, Josh (1993). The best of Josh McDowell: a ready defense. Nashville: T. Nelson. pp. 352–353. ISBN 0-8407-4419-6.

- ^ Sheridan 1986, p. 53.

- ^ Banerjee 1993.

- ^ Scheweig 2004, pp. 13–17

- ^ Elkman 1986.

- ^ "Chaitanya Charitamrita Madhya 20.165". Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ Richard Thompson, Ph. D. (December 1994). "Reflections on the Relation Between Religion and Modern Rationalism". ISKCON Communications Journal. 1 (2). Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ Mahony, W.K. (1987). "Perspectives on Krsna's Various Personalities". History of Religions. 26 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1086/463085. JSTOR 1062381. S2CID 164194548.

- ^ Bryant 2007, Chapter 2.

- ^ Rosen 2007.

- ^ Matchett 2001, pp. 44–64.

- ^ Bryant 2007, Chapter 3.

- ^ Vaudeville 1962, pp. 31–40.

- ^ Miller 1975, pp. 655–671.

- ^ Bryant 2003.

- ^ Bryant 2007, Chapter 4.

- ^ James Mulhern (1959) A History of Education: A Social Interpretation p. 93

- ^ Franklin Edgerton (1925) The Bhagavad Gita: Or, Song of the Blessed One, India's Favorite Bible pp. 87–91

- ^ Charlotte Vaudeville has said, it is the 'real Bible of Krsnaism'.

- ^ Matchett 2001, p. 107.

- ^ a b Klostermaier 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Radhakrishan(1970), ninth edition, Blackie and son India Ltd., p.211, Verse 6.47

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. "Bhaktivedanta VedaBase: Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Verse 8.15". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network (ISKCON). Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- ^ Matchett 2001, p. 153 Bhag. Purana 1.3.28 :ete cāṁśa-kalāḥ puṁsaḥ kṛṣṇas tu bhagavān svayam :indrāri-vyākulaṁ lokaṁ mṛḍayanti yuge yuge

- ^ 1.3.28 Archived 3 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Swami Prabhupada, A.C. Bhaktivedanta. "Srimad Bhagavatam Canto 1 Chapter 3 Verse 28". Bhaktivedanta Book Trust. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Sri Krishna". www.stephen-knapp.com. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ^ Dhanurdhara Swami (2000). Waves of Devotion. Bhagavat Books. ISBN 0-9703581-0-5.

- ^ "Waves of Devotion". www.wavesofdevotion.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2008. In Hari-namamr†a-vyakarana, Jiva Gosvami defines paribhasa-sutra as aniyame niyama-karini paribhasa: "A paribhasa-sutra implies a rule or theme where it is not explicitly stated." In other words, it gives the context in which to understand a series of apparently unrelated statements in a book.

- ^ Matchett 2001, p. 141

- ^ Matchett 2001, 10th canto transl.

- ^ a b Bryant 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Padma Purana Patala Khanda Fifth Canto, Motilal Bansaridas Publisher's Book 5 page 1950.

- ^ Lavanya Vemsani (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- ^ Danavir Goswami; Kusakratha Dasa, eds. (2006). Kr̥ṣṇa Comes to Earth (Śrī Garga-saṃhitā: Ist canto, pt. 2. ch. 7-13). Rupanuga Vedic College. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Varadpande, M. L. (2007). Love in Ancient India. Wisdom Tree. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-81-8328-217-8.

- ^ Elkman 1986; Gupta 2007; Bryant 2007, pp. 373–378.

- ^ Ramnarace 2014.

- ^ Elkman 1986; Gupta 2007; Bryant 2007, pp. 373–378; Gupta 2014.

- ^ Bryant 2007, pp. 479–480.

- ^ Beck 2005, pp. 67, 74.

- ^ Beck 1993, p. 199.

- ^ "Contents of the Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa Upaniṣad". 16 April 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Ranade, Ashok D. (2000). Kosambi, Meera (ed.). Intersections: socio-cultural trends in Maharashtra. London: Sangam. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-0863118241.

- ^ a b Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–112, 148–149. ISBN 978-1-139-91561-8.

- ^ Beck 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Bernier, Ronald M. (1997). Himalayan Architecture. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-8386-3602-2.

- ^ Vemsani 2016, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Pauwels 2003, pp. 124–180.

- ^ Hawley 2020, front matter.

- ^ Schweig 2005, p. 10.

- ^ McDermott, Rachel Fell (2005). "Bengali religions". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion: 15 Volume Set. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit, Mi: MacMillan Reference USA. pp. 824–832. ISBN 0-02-865735-7.

- ^ Brooks 1989.

- ^ Giuliano, Geoffrey (1997). Dark horse: the life and art of George Harrison. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-306-80747-5.

- ^ Schweig 2005.

- ^ What Does Tulsi Gabbard Believe?, Kelefa Sanneh, The New Yorker, Oktober 30, 2017.

- ^ Tulsi Gabbard Had a Very Strange Childhood, Kerry Howley, New York Intelligencer, Juni 11, 2019.

- ^ The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors by Kersey Graves

- ^ Jackson, John (1985). Christianity Before Christ. American Atheist Press. pp. 166. ISBN 0-910309-20-5.

Bibliography

[edit]- Archer, W. G. (2004) [1957]. The Loves of Krishna in Indian Painting and Poetry. Mineola, NY: Dover Publ. ISBN 0-486-43371-4.

- Banerjee, Samanta (1993). Appropriation of a Folk-heroine: Radha in Medieval Bengali Vaishnavite Culture. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. ISBN 8185952086.

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1968). "Review: Krishna: Myths, Rites, and Attitudes by Milton Singer; Daniel H. H. Ingalls". The Journal of Asian Studies. 27 (3): 667–670. doi:10.2307/2051211. JSTOR 2051211. S2CID 161458918.

- Basu, M. M. (1932). The Post-Caitanya Sahajiya Cult of Bengal. Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press.

- Beck, Guy L. (1993). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Studies in Comparative Religion. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0872498557.

- Beck, Guy L. (2005). "Krishna as Loving Husband of God: The Alternative Krishnology of the Rādhāvallabha Sampradaya". In Guy L. Beck (ed.). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 65–90. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1.

- Brooks, Charles R. (1989). The Hare Krishnas in India. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069100031X.

- Bryant, Edwin F. (2003). Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God; Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa, Book X; with Chapters 1, 6 and 29–31 from Book XI. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0140447997.

- Bryant, Edwin F., ed. (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6.

- Brzezinski, J. K. (1992). "Prabodhānanda, Hita Harivaṃśa and the Rādhārasasudhānidhi". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 55 (3): 472–497. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00003669. JSTOR 620194. S2CID 161089313.

- Carney, Gerald T. (2020). "Baba Premananda Bharati: his trajectory into and through Bengal Vaiṣṇavism to the West". In Ferdinando Sardella; Lucian Wong (eds.). The Legacy of Vaiṣṇavism in Colonial Bengal. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. Milton, Oxon; New York: Routledge. pp. 135–160. ISBN 978-1-138-56179-3.

- Chakravarti, Ramakanta (1985). Vaiṣṇavism in Bengal, 1486–1900. Calcutta: Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar.[permanent dead link]

- Chatterjee, Asoke (1995). "Srimadbhagavata and Caitanya-Sampradaya". Journal of the Asiatic Society. 37 (4): 1–14.

- Clémentin-Ojha, Catherine (1990). "La renaissance du Nimbarka Sampradaya au XVIe siècle. Contribution à l'étude d'une secte Krsnaïte". Journal Asiatique (in French). 278: 327–376. doi:10.2143/JA.278.3.2011219.

- Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Dandekar, R. N. (1987) [Rev. ed. 2005]. "Vaiṣṇavism: An Overview". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14. New York: MacMillan.

- Das, Sri Paritosh (1988). Sahajiyā Cult of Bengal and Pancha Sakhā Cult of Orissa. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.[permanent dead link]

- Dasgupta, Shashibhusan (1962) [1946]. Obscure Religious Cults as a Background to Bengali Literature (2nd rev. ed.). Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Datta, Amaresh, ed. (1988). "Gitagovinda". Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Devraj to Jyoti. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 1414–1423. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- De, Sushil Kumar (1960). Bengal's contribution to Sanskrit literature & studies in Bengal Vaisnavism. Indian studies, past & present. Calcutta: K.L. Mukhopadhyaya. OCLC 580601204.

- Elkman, Stuart Mark (1986). Jīva Gosvāmin's Tattvasandarbha: A Study on the Philosophical and Sectarian Development of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Movement. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120801873.

- Eschmann, Anncharlott; Kulke, Hermann; Tripathi, Gaya Charan, eds. (1978) [Rev. ed. 2014]. The Cult of Jagannath and the regional tradition of Orissa. South Asian Studies, 8. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 9788173046179.

- Feldhaus, Anne (1983). The religious system of the Mahānubhāva sect: the Mahānubhāva Sūtrapāṭha. South Asian studies, 12. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 9780836410051.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Glushkova, Irina (2000). "Norms and Values in the Varkari Tradition". In Meera Kosambi (ed.). Intersections: Socio-cultural Trends in Maharashtra. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 47–53. ISBN 81-250-1878-6.

- Goswami, Kunja Govinda (1956). A study of Vaiṣṇavism from the advent of the Sungas to the fall of the Guptas in the light of epigraphic, numismatic and other archaeological materials. Calcutta: Oriental Book Agency. ISBN 8120801873.[permanent dead link]

- Gupta, Ravi M. (2007). The Chaitanya Vaishnava Vedanta of Jiva Gosvami: When Knowledge Meets Devotion. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40548-5.

- Gupta, Ravi M., ed. (2014). Caitanya Vaiṣṇava Philosophy: Tradition, Reason and Devotion. Surray: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754661771.

- Guy, John (1992). "New evidence for the Jagannatha sect in seventeenth century Nepal". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 3rd Ser. 2 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1017/S135618630000239X. S2CID 162316166.

- Hardy, Friedhelm E. (1987). "Kṛṣṇaism". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 8. New York: MacMillan. pp. 387–392. ISBN 978-0-02897-135-3 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- Hardy, Friedhelm E. (1981). Viraha-Bhakti: The Early Development of Kṛṣṇa Devotion in South India. Oxford University South Asian Studies Series. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-564916-8.

- Hawley, John Stratton (2005). Three Bhakti Voices. Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195670851.

- Hawley, John Stratton (2020). Krishna's Playground: Vrindavan in the 21st Century. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190123987.

- Hayes, Glen Alexander (2005). "Contemporary Metaphor Theory and Alternative Views of Krishna and Rādhā in Vaishnava Sahajiyā". In Guy L. Beck (ed.). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 19–32. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1.

- Hein, Norvin (1986). "A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla". History of Religions. 25 (4): 296–317. doi:10.1086/463051. JSTOR 1062622. S2CID 162049250.

- Hine, Phil (2003). "For the Love of God: Variations of the Vaisnava School of Krishna Devotion". Ashé Journal. 2 (4).

- Hudson, D. (1983). "Vasudeva Krsna in Theology and Architecture: A Background to Srivaisnavism". Journal of Vaiṣṇava Studies (2).

- Iwao, Shima (June–September 1988). "The Vithoba Faith of Maharashtra: The Vithoba Temple of Pandharpur and Its Mythological Structure" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 15 (2–3). Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture: 183–197. ISSN 0304-1042. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- Jones, Constance A.; Ryan, James D. (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- Kennedy, Melville T. (1925). The Chaitanya Movement: A Study of the Vaishnavism of Bengal. The Religious Life of India. Calcutta: Association Press; Humphery Milford; Oxford University Press.

- Khan, Dominique-Sila (2002). The Pranami Faith: Beyond "Hindu" and "Muslim". Yoginder Sikand.

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2005). A Survey of Hinduism (3rd ed.). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-7081-4.

- Kulke, Hermann; Schnepel, Burkhard, eds. (2001). Jagannath Revisited: Studying Society, Religion, and the State in Orissa. Studies in Orissan society, culture, and history, 1. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-386-4.

- Lorenzen, David N. (1995). Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2025-6.

- Love Song of the Dark Lord: Jayadeva's Gītagovinda. Translated by Miller, Barbara Stoler. New York: Columbia University Press. 1977. ISBN 0231040288.

- McDaniel, June (2005). "Folk Vaishnavism and Ṭhākur Pañcāyat: Life and status among village Krishna statues". In Guy L. Beck (ed.). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. pp. 33–42. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1.

- Matchett, Freda (2001). Krsna, Lord or Avatara? the relationship between Krsna and Visnu: in the context of the Avatara myth as presented by the Harivamsa, the Visnupurana and the Bhagavatapurana. Surrey: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1281-X.

- Medhi, Kaliram (1978). Satyendranath Sarma (ed.). Studies in the Vaiṣṇava Literature & Culture of Assam. Assam Sahitya Sabha.

- Miller, Barbara S. (1975). "Rādhā: Consort of Kṛṣṇa's Vernal Passion". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 95 (4): 655–671. doi:10.2307/601022. JSTOR 601022.

- Miśra, Narayan (2005). Durga Nandan Mishra (ed.). Annals and Antiquities of the Temple of Jagannātha. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-747-8.

- Mukherjee, Prabhat (1981) [1940]. The History of Medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120602293.

- Mullick, Bulloram (1898). Krishna and Krishnaism. Calcutta: S.K. Lahiri & Co.

- Murthy, H.V. Sreenivasa (1973). Vaisnavism of Samkaradeva and Ramanuja: A Comparative Study. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Neog, Maheswar (1980). Early History of the Vaiṣṇava Faith and Movement in Assam: Śaṅkaradeva and His Times. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Patel, Gautam E. (2005). "Concept of God According to Vallabhacarya". In Ramkaran Sharma (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian Wisdom. Vol. 2. New Delhi; Varanasi: MacMillan. pp. 127–136.

- Pauwels, Heidi (2003). "Paradise Found, Paradise Lost: Hariram Vyas's Love for Vrindaban and what Hagiographers made of it". In Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara (ed.). Pilgrims, Patrons, and Place: Localizing Sanctity in Asian Religions. Asian Religions and Society Series. Vancouver, Toronto. pp. 124–180.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rajaguru, S.N. (1992). Inscriptions of Jagannath Temple and Origin of Sri Purusottam Jagannath. Vol. 1–2. Puri: Shri Jagannath Sanskrit Vishvavidyalaya.

- Ramnarace, Vijay (2014). Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa's Vedāntic Debut: Chronology & Rationalisation in the Nimbārka Sampradāya (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh.

- Redington, James D. (1992). "Elements of a Vallabhite Bhakti-synthesis". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 112 (2): 287–294. doi:10.2307/603707. JSTOR 603707.

- Rosen, Steven J. (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Contemporary Scholars Discuss the Gauḍīya Tradition. Foreword by E. C. Dimock (2nd ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120812352.

- Rosen, Steven J. (2007). Krishna's Song: A New Look at the Bhagavad Gita. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313345531.

- Rosenstein, Lucy (1998). "The Rādhāvallabha and the Haridāsā Samprādayas: A Comparison". Journal of Vaishnava Studies. 7 (1): 5–18.

- Rosenstein, Ludmila L. (1997). "The Devotional Poetry of Svami Haridas". A Study of Early Braj Bhasa Verse. Groningen Oriental Studies, 12. Groningen: Egbert Forsten.

- Sardella, Ferdinando; Wong, Lucian, eds. (2020). The Legacy of Vaiṣṇavism in Colonial Bengal. Routledge Hindu Studies Series. Milton, Oxon; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-56179-3.

- Sarma, Satyendranath (1966). The Neo-Vaiṣṇavite Movement and the Satra Institution of Assam. Gauhati University. OCLC 551510205.

- Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H., eds. (1987). The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Berkeley Religious Studies Series. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3.

- Schweig, Graham M. (2005). Dance of Divine Love: The Rڄasa Lڄilڄa of Krishna from the Bhڄagavata Purڄana, India's classic sacred love story. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11446-3.[permanent dead link]

- Sheridan, Daniel (1986). The Advaitic Theism of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Singh, Kunj Bihari (2004) [1963]. "Manipur Vaishnavism: A Sociological Interpretation". In Rowena Robinson (ed.). Sociology of Religion in India. Themes in Indian Sociology, 3. New Delhi: Sage Publ. India. pp. 125–132. ISBN 0-7619-9781-4.

- Sivaramkrishna, M.; Roy, Sumita, eds. (1996). Poet-Saints of India. New Delhi: Sterling Publ. ISBN 81-207-1883-6.

- Snell, Rupert (1991). The Eighty-four Hymns of Hita Harivaṃśa: An Edition of the Caurāsī Pada. Delhi; London: Motilal Banarsidass; School of Oriental and African Studies. ISBN 81-208-0629-8.

- Starza, O. M. (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art and Cult. Studies in South Asian culture, 15. Leiden; New York; Köln: Brill. ISBN 90-04-09673-6.

- Stewart, Tony K. (1986). "Singing the Glory of Lord Krishna: The "Srikrsnakirtana"". Asian Ethnology. 45 (1). JSTOR 1177851.

- Stewart, Tony K. (2010). The Final Word: The Caitanya Caritāmṛta and the Grammar of Religious Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539272-2.

- Toffin, Gérard (2012). "The Power of Boundaries: Transnational Links among Krishna Pranamis of India and Nepal". In John Zavos; et al. (eds.). Public Hinduisms. New Delhi: Sage Publ. India. pp. 249–254. ISBN 978-81-321-1696-7.

- Vaudeville, Ch. (1962). "Evolution of Love-Symbolism in Bhagavatism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 82 (1): 31–40. doi:10.2307/595976. JSTOR 595976.

- Vemsani, Lavanya (2016). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names. Santa Barbara, Ca; Denver, Co; Oxford: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- Welbon, G. R. (1987). "Vaiṣṇavism: Bhāgavatas". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-02897-135-3.

- White, Charles S. J. (1977). The Caurāsī Pad of Śri Hit Harivaṃś: Introduction, Translation, Notes, and Edited Braj Bhaṣa. Asian studies at Hawaii, 16. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 9780824803599. ISSN 0066-8486.

- White, Charles S. J.; Redington, James D. (1990). "Vallabhacarya on the Love Games of Krsna". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 110 (2): 373–374. doi:10.2307/604565. JSTOR 604565.

Further reading

[edit]- Anand, D. (1992). Krishna: The Living God of Braj. New Delhi: Shakti Malik Abhinav Publ. ISBN 81-7017-280-2.

- Bhattacharya, Sunil Kumar (1996). Krishna-cult in Indian Art. New Delhi: M. D. Publ. Pvt. ISBN 81-7533-001-5.

- Case, Margaret H. (2000). Seeing Krishna: The Religious World of a Brahman Family in Vrindavan. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513010-3.

- Couture, André (2006). The emergence of a group of four characters (Vasudeva, Samkarsana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha) in the Harivamsa: points for consideration. Journal of Indian Philosophy 34,6. pp. 571–585.

- Das, Kalyani (1980). Early Inscriptions of Mathurā: A Study. Punthi Pustak.[permanent dead link]

- Majumdar, Asoke Kumar (July–October 1955). "A Note on the Development of Radha Cult". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 36 (3/4): 231–257. JSTOR 44082959.

- Mishra, Baba (1999). "Radha and her contour in Orissan culture" in Orissan history, culture and archaeology. In Felicitation of Prof. P.K. Mishra. Ed. by S. Pradhan. (Reconstructing Indian History & Culture 16). New Delhi; pp. 243–259.

- Nash, J. (2012). "Re-examining Ecological Aspects of Vrindavan Pilgrimage". In L. Manderson; W. Smith; M. Tomlinson (eds.). Flows of Faith. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 105–121. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2932-2_7. ISBN 978-94-007-2931-5.

- Singer, M. (1966). Krishna: Myths, Rites, and Attitudes. Honolulu: East-West Center Press.

- Sinha, K.P. (1997). A critique of A.C. Bhaktivedanta. Calcutta.