Kosta Pećanac

vojvoda Kosta Pećanac | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Константин Миловановић |

| Birth name | Konstantin Milovanović |

| Nickname(s) | Pećanac |

| Born | 1879 Dečani, Kosovo Vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | May–June 1944 (aged 65) Nikolinac, German occupied territory of Serbia |

| Place of burial | On the road between Soko Banja – Knjaževac |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1903–1912 1912–1918 1941–1944 |

| Rank | vojvoda |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | |

Konstantin "Kosta" Milovanović Pećanac (Serbian Cyrillic: Константин "Коста" Миловановић Пећанац; 1879–1944) was a Serbian and Yugoslav Chetnik commander (vojvoda) during the Balkan Wars, World War I and World War II. Pećanac fought on the Serbian side in both Balkan Wars and World War I, joining the forces of Kosta Vojinović during the Toplica uprising of 1917. Between the wars he was an important leader of Chetnik veteran associations, and was known for his strong hostility to the Yugoslav Communist Party, which made him popular in conservative circles. As president of the Chetnik Association during the 1930s, he transformed it into an aggressively partisan Serb political organisation with over half a million members. During World War II, Pećanac collaborated with both the German military administration and their puppet government in the German-occupied territory of Serbia.[1]

Just before the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the Yugoslav government provided Pećanac with funds and arms to raise guerrilla units in southern Serbia, Macedonia and Kosovo. He formed a detachment of about 300 men, mostly in the Toplica river valley in southern Serbia, which avoided destruction during the invasion. In the first three months after the surrender, Pećanac gathered more troops from Serb refugees fleeing Macedonia and Kosovo. However, his Chetniks fought only Albanian groups in the region, and did not engage the Germans. Following the uprising in the occupied territory in early July 1941, Pećanac quickly resolved to abandon resistance against the occupiers, and by the end of August had concluded agreements with the German occupation forces and the puppet government of Milan Nedić to collaborate with them and fight the communist-led Partisans. In July 1942, rival Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović arranged for the Yugoslav government-in-exile to denounce Pećanac as a traitor, and his continuing collaboration with the Germans ruined what remained of the reputation he had developed in the Balkan Wars and World War I.

The Germans rapidly realised that Pećanac's Chetniks, whose numbers had grown to 8,000, were inefficient and unreliable, and even the Nedić government had no confidence in them. They were completely disbanded by March 1943. Pećanac was interned by the Nedić regime for some time, and was killed by agents of Mihailović in May or June 1944.

Early life

[edit]Kosta Milovanović was born in a village near Dečani in 1879, although some sources mistakenly identify the year as 1871. His father Milovan was a guardian of the Visoki Dečani monastery. Pećanac's father and his brother Milosav fought in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. In 1883, both of his parents were killed in an attack by Albanians on the monastery. After that point, Pećanac was looked after by his uncle in the village of Đurakovac near Peć for an unknown amount of time.[2]

He arrived in Serbia in 1892 at the age of 14 and worked as a mercenary. When he was 21, he was called up for army service and served in the engineer corps, becoming a reserve officer. He later worked with the border gendarmerie near Vranje as a corporal. Pećanac was discharged at some point for reasons unknown and later joined the Chetniks. While serving with them he was given the nickname "Pećanac", derived from the name of the town in which he grew up.[3]

Macedonia and the Balkan Wars

[edit]In 1895, war broke out in Macedonia against the Ottoman Empire. Pećanac joined the Serbian Chetnik Organization in 1903, and fought against the Ottoman army in several significant battles including that of Šuplja Stena (near Pčinja) and Čelopek (near Staro Nagoričane).[4] The deacon of the Vladika of Žiča and commander (Serbo-Croatian: vojvoda, војвода) Jovan Grković-Gapon suggested awarding Pećanac the title of vojvoda; at a Christmas-day meeting in 1904, Pećanac received the title at the age of 25. In the period between 1905 and 1907, he led several major battles against the Ottoman army in the Skopje region.[5] In 1908, Pećanac married Sofia Milosavljević from the town of Aleksinac. He went on to father four children with her.[6] In 1910, as the struggles in Macedonia intensified, he left his children and pregnant wife, and returned to the battlefield.[7]

In the First Balkan War, fought from October 1912 to May 1913, Pećanac was mobilised in the Serbian Third Army, holding the rank of sergeant in the Morava Division. He took part in the defeat of the Albanians in Merdare, the Battle of Kumanovo and the capture of Metohija.[7] During the Second Balkan War, fought from 29 June to 10 August 1913, Pećanac is believed to have been stationed at the front at Kitka on Osogovo Mountain along the Zletovska and Bregalnica rivers. There, his division took part in the Battle of Bregalnica with the Bulgarians. After the Bulgarian attacks failed, they sent parliamentarians to seek a truce, but the Serbian side refused and the fighting continued. After his division had endured six days of heavy fighting, the Bulgarians were defeated at Grljani near Vinica.[8]

World War I

[edit]Following the disastrous end to the Serbian campaign in late 1915, Pećanac escaped to Corfu along with the retreating Serbian army and government, and ultimately joined the Salonika front. In 1915, Pećanac had received various medals for his "merit in fighting" including three gold medals for bravery, one for military virtue, and the Order of the Star of Karađorđe (4th Class) for his service in World War I and possibly also for his prior military accomplishments.[9]

In September 1916, the Serbian High Command sent then-Lieutenant Pećanac by air to Mehane (south-west of Niš in the Toplica region) to prepare a guerrilla uprising in support of a planned Allied offensive. There, Pećanac contacted several groups of guerrillas, known as comitadji. Pećanac joined forces with local leader Kosta Vojinović, and they both established headquarters on Mount Kopaonik. Rivalry quickly developed between the two leaders, mainly because Pećanac only had orders to prepare to support the planned Allied offensive, but Vojinović was conducting operations that might result in pre-emptive action by the Bulgarian occupation forces. Matters came to a head in January – February 1917 when the Bulgarians began conscripting local Serbs for military service. At a meeting of guerrilla leaders to discuss whether they should commence a general uprising, Pećanac was outvoted. However, events had overtaken the leaders, and they were essentially joining a popular uprising that was already underway. After guerrillas under Pećanac's command engaged the Bulgarians, he was hailed as a leader of the resistance, although he had serious reservations about the eventual outcome once the Bulgarians and Austro-Hungarians committed large numbers of troops to subdue the uprising. The guerrillas were closing on Niš in early March when the occupying forces went on the offensive. Pećanac advised his fighters to hide out in the woods and mountains, while Vojinović ordered his to fight to the death. By 25 March, the uprising had been crushed.[10] Pećanac's participation in the rebellion came at a great personal cost; three of his children died whilst in Bulgarian internment.[11]

In April 1917, Pećanac re-emerged with his guerrillas, attacking a railway station, destroying a bridge and raiding a Bulgarian village on the border. Pećanac avoided a further offensive by the occupation forces in July by disappearing into the mountains once again. After emerging for a short time, in September–October 1917 Pećanac again dispersed his guerrillas and infiltrated the Austro-Hungarian occupied zone, where he remained in hiding until mid-1918.[12] During his period in hiding, he met with the Kosovar Albanian leader Azem Galica to discuss joint actions against the occupation forces.[13]

Interwar period

[edit]Pećanac was the most prominent figure in the Chetnik movement during the interwar period.[14] During the 1920 Constitutional Assembly elections for the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Prime Minister Nikola Pašić sent Pećanac to the Sandžak with orders to intimidate the local Muslim population in the hope of keeping the turnout low.[15] In the same year, attempts by the Yugoslav government to disarm and conscript Kosovo Albanians were met by revolts. Pećanac was sent to Kosovo to form detachments made up of local Serbs to fight the rebels. This resulted in rebel attacks on Serb villages.[16]

Pećanac had a leading role in the Association against Bulgarian Bandits, an organisation that arbitrarily terrorised Bulgarians in the Štip region.[14] He also served as a commander with the Organization of Yugoslav Nationalists (ORJUNA).[17] In 1922, after the failed assassination of a prominent People's Radical Party member in the Deževa district, the authorities sent Pećanac and his Chetniks to fight Jusuf Mehonjić, who was behind the attempted assassination, and his unit of outlaws. In this action, Pećanac's Chetniks killed 28 Muslim inhabitants of the village of Starčevići near Tutin. They failed to catch Mehonjić, and ultimately Mehonjić's unit defeated Pećanac's Chetniks in a battle.[18] Pećanac was present as a member of parliament at the assassination of Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) leader Stjepan Radić and HSS deputies Pavle Radić and Đuro Basariček on 20 June 1928. Prior to the shooting, he was accused by HSS deputy Ivan Pernar of being responsible for a massacre of 200 Muslims in 1921.[19]

Pećanac became the president of the Chetnik Association in 1932.[20] By opening membership of the Chetnik Association to new younger members that had not served in World War I, he grew the organisation during the 1930s from a nationalist veterans' association focused on protecting veterans' rights to an aggressively partisan Serb political organisation with 500,000 members throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[21] During this period, Pećanac formed close ties with the far-right Yugoslav Radical Union government of Milan Stojadinović.[22] Pećanac was known for his hostility to the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, which made him popular with conservatives, especially those in Stojadinović's party.[23][24]

World War II

[edit]Shortly before the Axis invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941, Pećanac was requested by the Yugoslav Ministry of the Army and Navy to prepare for guerrilla operations and guard the southern area of Serbia, Macedonia, and Kosovo from pro-Bulgarians and pro-Albanians rebels. He was given money and weapons, and managed to arm several hundred men in the Toplica River valley in southern Serbia. Pećanac's force remained intact after the German occupation of Serbia and supplemented its strength from Serb refugees fleeing Macedonia and Kosovo. Pećanac's detachments fought against Albanian bands in the early summer of 1941.[20] At this time and for a considerable time after, only detachments under Pećanac were identified by the term "Chetnik".[25] With the rise of the communist Partisans, Pećanac gave up any interest in resistance and by late August reached agreements with both the Serbian puppet government and the German authorities to carry out attacks against the Partisans.[25][26]

While he was concluding arrangements with the Germans, on 18 August 1941 Pećanac received a letter from Draža Mihailović requesting an agreement be reached where Pećanac would control the Chetniks south of the Western Morava River while Mihailović would control the Chetniks in all other areas.[27] Pećanac declined his request and suggested that he might offer Mihailović the chief of staff position and recommended Mihailović's detachments disband and join his detachments. In the meantime, Pećanac had arranged for the transfer of several thousand of his Chetniks to the Serbian Gendarmerie to act as German auxiliaries.[28]

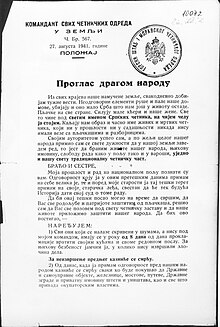

On 27 August, Pećanac issued an open "Proclamation to the Dear People", in which he portrayed himself as a defender and protector of Serbs and called "on detachments that have been formed without his approval" to come together under his command. He demanded that individuals hiding in the forests immediately return to their homes and that acts of sabotage against the occupiers cease or the perpetrators would face death.[29]

In September 1941, some of Pećanac's subordinates broke ranks to join with the Partisans in fighting the Germans and their Serbian auxiliaries. In the Kopaonik region, a previously loyal subordinate of Pećanac began attacking local gendarmerie stations and clashing with armed bands of Albanian Muslims. By the end of October, the Germans decided to stop arming the "unreliable" elements within Pećanac's Chetniks, and attached the remainder to their other Serbian auxiliary forces.[30] On November 16, German occupier held a meeting in Niš between representatives of Nedić's government and prominent Albanian collaborators from Kosovo to stop continuation of ethnic and religious violence between collaborationist groups. Albanian side blamed Serbian side as instigator of the conflict citing involvement of Pećanac's men on attack on Novi Pazar. Pećanac was forced to answer to quisling government's Minister of Interior Milan Aćimović and German representative. He said that his commander Mešan Đurović possibly participated in the attack and banned him from attacking Albanian forces in the region. In return, Germans guaranteed that Albanian forces will enter Serbian territory less often.[31]

On 7 October 1941, Pećanac sent a request to Milan Nedić, the head of the Serbian puppet government, for stronger organisation, supplies, arms, salary funds, and more. Over time, his requests were fulfilled and a German liaison officer was appointed at Pećanac's headquarters to help coordinate actions. According to German data, on 17 January 1942 a total of 72 Chetnik officers and 7,963 men were being provided for by the Serbian Gendarmerie Command. This fell short of the maximum authorised size of 8,745 men and included two or three thousand of Mihailović's Chetniks who were legalised in November 1941.[25] In the same month, Pećanac sought permission from the Italians for his forces to move into eastern Montenegro, but was refused over Italian concerns that the Chetniks would move into the Sandžak.[32]

In April 1942, the German Commanding General in Serbia, General der Artillerie (General) Paul Bader, issued orders giving unit numbers C–39 to C–101 to the Pećanac Chetnik detachments, which were put under the command of the local German division or area command post. These orders also required the deployment of a German liaison officer with all detachments engaged in operations, and limited their movement outside their assigned area. Supply of arms and ammunition was also controlled.[33] In July 1942, Mihailović arranged for the Yugoslav government-in-exile to denounce Pećanac as a traitor.[34] His continuing collaboration ruined what remained of the reputation he had developed in the Balkan Wars and World War I.[35]

The Germans soon found that Pećanac's units were inefficient, unreliable, and of little military use. Pećanac's Chetniks regularly clashed and had rivalries with other German auxiliaries, such as the Serbian State Guard and Serbian Volunteer Command, as well as with Mihailović's Chetniks.[36] The Germans and the puppet government commenced disbanding them in September 1942, and all but one were dissolved by the end of 1942. The last detachment was dissolved in March 1943. Pećanac's followers were dispersed to other German auxiliary forces, German labour units, and prisoner-of-war camps. Many deserted to join Mihailović. Nothing is known of Pećanac's activities in the months that followed except that he was interned for some time by the Serbian puppet government.[37]

Death

[edit]Accounts of Pećanac's capture and death vary. According to one account, Pećanac, four of his leaders and 40 of their followers were captured by forces loyal to Mihailović in February 1944. All were killed within days except Pećanac, who remained in custody to write his war memoirs before being executed on 5 May 1944.[36] Another source states he was assassinated on 6 June 1944 by Chetniks loyal to Mihailović.[38]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hehn 1971, p. 350; Pavlowitch 2002, p. 141, the official name of the occupied territory was the "Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia".

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003a.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003b.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003c.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003d.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003e.

- ^ a b Pavlović & Mladenović 2003f.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003g.

- ^ Pavlović & Mladenović 2003h.

- ^ Mitrović 2007, pp. 248–259.

- ^ Newman 2015, p. 108.

- ^ Mitrović 2007, pp. 261–273.

- ^ Malcolm 2002, p. 262.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 47.

- ^ International Crisis Group 8 April 2005.

- ^ Malcolm 2002, p. 274.

- ^ Newman 2012, p. 158.

- ^ Živković 2017, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Glenny 2012, p. 410.

- ^ a b Tomasevich 1975, p. 126.

- ^ Singleton 1985, p. 188.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Milazzo 1975, p. 19.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Tomasevich 1975, p. 127.

- ^ Roberts 1973, p. 21.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 128.

- ^ Milazzo 1975, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Živković 2017, p. 268.

- ^ Milazzo 1975, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 195.

- ^ Roberts 1973, p. 63.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2007, p. 59.

- ^ a b Lazić 2011, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, pp. 128, 195.

- ^ Tomasevich 1975, p. 260.

References

[edit]Books

[edit]- Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: 1804–2012. London, England: Granta Books. ISBN 978-1-77089-273-6.

- Lazić, Sladjana (2011). "The Collaborationist Regime of Milan Nedić". In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola (eds.). Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1.

- Malcolm, Noel (2002). Kosovo: A Short History. London, England: Pan. ISBN 978-0-330-41224-7.

- Milazzo, Matteo J. (1975). The Chetnik Movement & the Yugoslav Resistance. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1589-8.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

- Newman, John Paul (2012). "Paramilitary Violence in the Balkans". In Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John (eds.). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe After the Great War. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968605-6.

- Newman, John Paul (2015). Yugoslavia in the Shadow of War: Veterans and the Limits of State Building, 1903–1945. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10707-076-9.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History Behind the Name. London, England: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-476-6.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2007). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1973). Tito, Mihailović and the Allies 1941–1945. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0773-0.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Živković, Milutin D. (2017). Санџак 1941–1943 [Sandžak 1941–1943] (Doctoral) (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: University of Belgrade. OCLC 1242119546.

Journals

[edit]- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941–1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 13 (4). Edmonton: University of Alberta: 344–373. doi:10.1080/00085006.1971.11091249. JSTOR 40866373.

Online sources

[edit]- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (29 April 2003). "Rođen i odrastao u Turskom mraku" [Born and Raised in Turkish Darkness]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (30 April 2003). "Bežanje u Srbiju" [Fleeing to Serbia]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (4 May 2003). "Zakletva na hleb i revolver" [Oath on Bread and Revolver]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (5 May 2003). "Voskom zavaravali glad" [They Waxed Hunger with Wax]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian).

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (6 May 2003). "Sofija opčinila Kostu Pećanca" [Sofija Enchanted Kosta Pećanac]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (8 May 2003). "U ratu protiv Turske" [In the War against Turkey]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (11 May 2003). "Drugi balkanski rat" [The Second Balkan war]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Pavlović, Momčilo; Mladenović, Božica (12 May 2003). "Mobilizacija Srpske vojske" [Mobilization of the Serbian Army]. Glas javnosti (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- International Crisis Group (8 April 2005). "Serbia's Sandzak: Still Forgotten" (PDF). Crisis Group Europe Report. International Crisis Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- 1879 births

- 1944 deaths

- People from Deçan

- People from Kosovo vilayet

- Kosovo Serbs

- Chetnik personnel of World War II

- Serbian military personnel of World War I

- Serbian military personnel of the Balkan Wars

- Chetniks of the Macedonian Struggle

- Serbian anti-communists

- Serbian mercenaries

- Executed Serbian collaborators with Fascist Italy

- Executed Serbian collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Recipients of the Medal for Bravery (Serbia)

- Royal Serbian Army soldiers

- Emigrants from the Ottoman Empire to Serbia

- Pećanac Chetniks