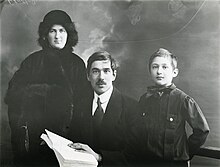

Korney Chukovsky

Korney Chukovsky | |

|---|---|

On July 1958. | |

| Born | Nikolay Vasilyevich Korneychukov 31 March 1882 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 28 October 1969 (aged 87) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, translator, literary critic, journalist |

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky (Russian: Корне́й Ива́нович Чуко́вский, IPA: [kɐrˈnʲej ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ tɕʊˈkofskʲɪj] ; 31 March NS 1882 – 28 October 1969) was one of the most popular children's poets in the Russian language.[1] His catchy rhythms, inventive rhymes and absurd characters have invited comparisons with the American children's author Dr. Seuss.[2][3] Chukovsky's poems Tarakanische ("The Monster Cockroach"), Krokodil ("Crocodile"), Telefon ("The Telephone"), Chukokkala, and Moydodyr ("Wash-'em-Clean") have been favorites with many generations of Russophone children. Lines from his poems, in particular Telefon, have become universal catch-phrases in the Russian media and everyday conversation. He adapted the Doctor Dolittle stories into a book-length Russian poem as Doctor Aybolit ("Dr. Ow-It-Hurts"), and translated a substantial portion of the Mother Goose canon into Russian as Angliyskiye Narodnyye Pesenki ("English Folk Rhymes"). He also wrote very popular translations of Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, Rudyard Kipling, O. Henry, and other authors,[4] and was an influential literary critic and essayist.

Early life

[edit]Originally named Nikolay Vasilyevich Korneychukov (Russian: Николай Васильевич Корнейчуков), the writer reworked his original family name into his now familiar pen-name while working as a journalist at Odessa News in 1901. He was born in Saint Petersburg as the illegitimate son of Yekaterina Osipovna Korneychukova and of Emmanuil Solomonovich Levenson, a man from a wealthy Russian Jewish family (his legitimate grandson was mathematician Vladimir Rokhlin). Levenson's family did not permit his marriage to Korneychukova, and the couple was eventually forced to separate. Korneychukova moved to Odessa with her two children, Nikolay and his sister Marussia.[5] Levenson supported them financially for some time, until his marriage to another woman. Nikolay studied at the Odessa gymnasium, where one of his classmates was Vladimir Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Later, the gymnasium expelled Nikolay for his "low origin" (a euphemism for illegitimacy). He had to obtain his secondary-school and university diplomas by correspondence.

He taught himself English and, in 1903–05, he served as the London correspondent of an Odessa newspaper, although he spent most of his time at the British Library instead of in the parliamentary press gallery. Back in Russia, Chukovsky started translating English works and published several analyses of contemporary European authors, which brought him in touch with leading personalities of Russian literature and secured the friendship of Alexander Blok. Chukovsky's English was not idiomatic - he had taught himself to speak it by reading and he thus pronounced English words in a distinctly odd manner, and it was difficult for people to understand him in England.[6] His influence on Russian literary society of the 1890s is immortalized by satirical verses of Sasha Chorny, including Korney Belinsky (an allusion to the famous critic Vissarion Belinsky (1811–1848)). Korney Chukovsky published several notable literary titles, including From Chekhov to Our Days (1908), Critique stories (1911) and Faces and masks (1914). He also published a satirical magazine called Signal (1905–1906) and was arrested for "insulting the ruling house", but was acquitted after six months of investigative incarceration.

Later life and works

[edit]

It was at that period that Chukovsky produced his first fantasies for children. The girl from his famous fairy tale poem "Crocodile" was inspired by Lyalya, daughter of his long-time friend, publisher Zinovii Grzhebin.[7] A bibliographical sketch for Chukovsky in The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia and Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature characterized "Crocodile", along with other Chukovsky's verse tales as follows, "clockwork rhythms and air of mischief and lightness in effect dispelled the plodding stodginess that had characterized pre-revolutionary children's poetry."[8] Subsequently, they were adapted for theatre and animated films, with Chukovsky as one of the collaborators. Sergei Prokofiev and other composers even adapted some of his poems for opera and ballet. His works were popular with emigre children as well, as Vladimir Nabokov's complimentary letter to Chukovsky attests.

During the Soviet period, Chukovsky edited the complete works of Nikolay Nekrasov and published From Two to Five (1933), a popular guidebook to the language of children.

As his diaries attest, Chukovsky used his popularity to help the authors persecuted by the regime including Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Alexander Galich and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[citation needed] He was the only Soviet writer who officially congratulated Boris Pasternak on winning the Nobel Prize.

At one point his fantastic writings for children (Bibigon, Moydodyr, Barmaley from Doctor Aybolit, etc.) were under severe criticism. Nadezhda Krupskaya was an initiator of this campaign against "Chukovshshina",[9] but criticism also came also from children's writer Agniya Barto.[citation needed]

Chukovsky extensively wrote about the translation process and critiqued other translators. In 1919, he co-wrote with Nikolai Gumilev a brochure called Printsipy khudozhestvennogo perevoda (English: Principles of Artistic Translation). In 1920, Chukovsky revised it, and he substantially rewrote and expanded it numerous times throughout his life without Gumilev.[10] Chukovsky's subsequent revisions were done in 1930 (re-titling it Iskusstvo perevoda [English: The Art of Translation]), 1936, 1941 (re-titling it Vysokoe iskusstvo [English: A High Art]), 1964, and his final revision was published in his Collected Works in 1965–1967.[11] In 1984, Lauren G. Leighton published her English translation of Chukovsky's final revision, and titled it The Art of Translation: Kornei Chukovsky's A High Art.

Starting in the 1930s, Chukovsky lived in the writers' village of Peredelkino near Moscow, where he is now buried.

For his works on the life of Nekrasov he was awarded a Doktor nauk in philology. He also received the Lenin Prize in 1962 for his book, Mastery of Nekrasov and an honorary doctorate from University of Oxford in 1962.

Family

[edit]

On May 26, 1903, Chukovsky married Maria (Maria Borisovna Chukovskaya) née Goldfeld, daughter of Aron-Ber and Tauba.

His daughter, Lydia Chukovskaya (1907–1996), is remembered as a noted writer, memoirist, philologist and lifelong assistant and secretary of the poet Anna Akhmatova.

His son, Nikolai Chukovsky (1904–1965) was a writer and translator.

His son Boris (1910—1941 went missing in action during World War II.

His daughter Maria (1920–1931), affectionately called "Mura", a character in some of his children's poems and stories, died in her childhood from tuberculosis.

Mathematician Vladimir Abramovich Rokhlin was his nephew.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Daria Aminova, Korney Chukovsky: The children’s author who wrote against all odds, rbth.com. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Russia Profile - Print edition". Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Madrid, Anthony (19 February 2020). "Russia's Dr. Seuss". The Paris Review. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Матусова, Олена (2 February 2016). "Рідна мова Корнія Чуковського – українська". Радіо Свобода.

- ^ Goloperov, Vadim (25 November 2016). "Korney Chukovsky: Odessa's Famous And Also Unknown Writer". The Odessa Review. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Ippolitov 2003.

- ^ An unsigned bibliographical sketch for Chukovsky in:

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia, 1993, p. 300

- Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature, 1995, p. 242

- ^ «Полная безыдейность, переходящая в идейность обратного порядка» Борьба с «чуковщиной»

- ^ Leighton, Lauren G. (1984). "The Translator's Introduction". The Art of Translation: Kornei Chukovsky's A High Art. By Chukovsky, Kornei. The University of Tennessee Press. p. xxxi. ISBN 9780870494055.

- ^ Leighton, Lauren G. (1984). "The Translator's Introduction". The Art of Translation: Kornei Chukovsky's A High Art. By Chukovsky, Kornei. The University of Tennessee Press. pp. xxxi–xxxii. ISBN 9780870494055.

Sources

[edit]- Ippolitov, S. S. (2003). "Гржебин Зиновий Исаевич (1877 1929)" [Grzhebin Zinovii Isaevich (1877 1929)]. Новый Исторический Вестник (in Russian) (9). The New Historical Bulletin: 143–166.

External links

[edit]Works by Chukovsky

[edit]- Popular works by Chukovsky, at Ryfma.com (in Russian)

- Живой как жизнь ('Alive as life itself'), a humorous and anti-prescriptivist discussion of the Russian language (in Russian)

- Selected works of Chukovsky, at the Stikhiia poetry archive (in Russian)

Works about Chukovsky

[edit]- Chukfamily.ru Materials about three generations of the Chukovsky family: Korney, Lidiya and Elena (in Russian)

- Biography of Chukovsksy (in Russian)

- "On the 120th Anniversary of Chukovsky's Birth", by essayist Dmitrii Bykov (in Russian)

- 1882 births

- 1969 deaths

- Writers from Saint Petersburg

- People from Sankt-Peterburgsky Uyezd

- Russian people of Jewish descent

- Writers from the Russian Empire

- Recipients of the Lenin Prize

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Children's poets

- Literary translators

- English–Russian translators

- Translators from English

- Translators of Oscar Wilde

- Translators of William Shakespeare

- Soviet children's writers

- Soviet essayists

- Soviet literary historians

- Soviet male poets

- Soviet male writers

- Deaths from hepatitis