Akala (rapper)

Akala | |

|---|---|

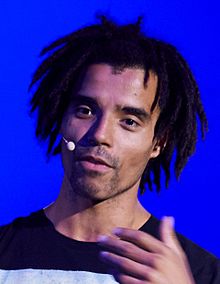

Akala in 2014 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Kingslee James McLean Daley |

| Born | 1 December 1983 [1] Crawley, West Sussex, England [1] |

| Origin | Kentish Town, London, England |

| Genres | British hip hop |

| Occupation(s) | Rapper, writer and activist |

| Years active | 2003–present |

| Labels | Immovable Ltd (Illa State Records) |

| Website | akalamusic |

Kingslee James McLean Daley (born 1 December 1983),[1] known professionally as Akala, is an English rapper, writer and activist from Kentish Town, London. In 2006, he was voted the Best Hip Hop Act at the MOBO Awards[2] and has been included on the annual Powerlist of the 100 most influential Black British people in the UK, most recently making the 2021 edition.[3][4]

Early life and education

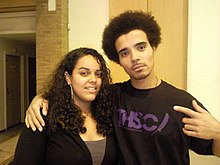

[edit]Daley was born in Crawley, West Sussex,[1] in 1983 to a Scottish mother and Jamaican father who separated before he was born, and grew up with his mother in Kentish Town, north London.[5][6] He has recalled the day he realised that his mother was white,[7] and was embarrassed by her whiteness.[8] His mother had educated him about black history and introduced him to radical black thinkers, yet there would always remain a racial dimension to those relationships.[9] Daley's older sister is rapper Ms. Dynamite.

His stepfather was a stage manager at the Hackney Empire theatre, and he often visited it before his teens.[10] His mother enrolled him in a pan-African Saturday school, about which he states "I benefited massively from a specifically black community-led self-education tradition that we don't talk about very much because it doesn't fit with the image [of black families]".[11] When accepting honorary degrees, he thanked "the entire Caribbean pan-African community that helped me through school and encouraged an intellectual curiosity and self development from a very young age."[12]

At age six, Daley's state primary school put him in a special needs group for pupils with learning difficulties and English as a second language.[10] He attended Acland Burghley School for secondary education. Daley saw a friend attacked with a meat cleaver to the skull when he was 12, and carried a knife himself for a period.[11] He went on to achieve ten GCSEs and took maths a year early. He has said he "was in the top 1 per cent of GCSEs in the country. [I] got 100 per cent in [my] English exam."[11] As a teenager, Daley focused on football, being on the schoolboy books of both West Ham United and AFC Wimbledon, and dropped out of college.[10] He is a fan of Arsenal.[13] Daley did not attend university, but has said he often envies those who do.[14]

Daley has two honorary degrees in recognition of his educational work. On 23 June 2018, he received an honorary doctorate from Oxford Brookes University as a Doctor of Art.[15] On 31 July 2018, he received an honorary degree from Brighton University.[16]

Musical career

[edit]2003–2009: Early years and breakthrough

[edit]

Daley got his stage name from Acala, a Buddhist term for "immovable",[17] and started releasing music in 2003 from his own independent music label, Illa State Records. He released his first mixtape, The War Mixtape, in 2004.[18]

In 2006, he released his first album, It's Not a Rumour. This proved to be his breakthrough album, containing the single "Shakespeare" (a reference to his self-proclaimed title "The Black Shakespeare") which made the BBC Radio 1 playlist.[19] His work was recognised with the MOBO Award for Best Hip Hop Act.[20] Additionally in 2006, a mixtape, A Little Darker, was released under the name "Illa State", featuring Akala and his sister, Ms. Dynamite, as well as cameo appearances by many other artists.[21]

Daley appeared for a live session on BBC Radio 1Xtra where he was challenged to come up with a rap containing as many Shakespeare play titles as he could manage, he wrote and performed a minute-long rap containing 27 different Shakespeare play titles in under half an hour and later recorded these lyrics in the studio and turned it into the single "Comedy Tragedy History".[22]

In 2007, Daley released his second album, Freedom Lasso, containing the "Comedy Tragedy History" track. The song "Love in my Eyes" heavily sampled Siouxsie and the Banshees' song "Love in a void" with the voice of Siouxsie Sioux.[23] In 2008, The War Mixtape Vol. 2 was released, along with an EP of acoustic remixes.[24]

2010–present: Doublethink, Knowledge Is Power, and beyond

[edit]

Daley's third studio album, DoubleThink, was released in 2010, and holds a strong theme of George Orwell's popular novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.[25] DoubleThink contains tracks such as "Find No Enemy" and "Yours and My Children" detailing some of the sights he saw on his trip to Brazil.[26] In November 2010, Daley headlined a live performance at the British Library, to launch the "Evolving English" exhibition and featured performances by British poet Zena Edwards, comedian Doc Brown and British rapper Lowkey which also included Daley taking part in a hip hop panel discussion alongside Saul Williams, U.S professor MK Asante and Lowkey.[27][28] Daley appeared on Charlie Sloth's show on Radio 1Xtra on 18 July 2011, performing "Fire in the Booth", and after the great reception it received he returned again in May 2012 and provided "Part 2".[29]

In May 2012, Daley released a two-part mixtape, Knowledge Is Power, containing "Fire in the Booth", and followed the release with a promotional tour in the autumn of 2012.[citation needed] In March 2013, Daley announced via his social media feeds that his fourth album would be released in May 2013, pushing back the future EP The Ruin of Empires to later in 2013.[citation needed] His fourth album, The Thieves Banquet, was released on 27 May 2013, including the songs "Malcolm Said It", "Maangamizi" and "Lose Myself" (feat. Josh Osho).[30]

Live performances

[edit]

In 2007, Daley was the first hip hop artist to perform his own headline concert in Vietnam.[31] He has performed at various U.K. festivals, including V Festival, Wireless, Glastonbury, Reading and Leeds Festivals, Parklife, Secret Garden Party and Isle of Wight, and has supported artists such as Christina Aguilera,[32] MIA,[33] Richard Ashcroft,[34] Audiobullys,[35] DJ Shadow,[36] The Gotan Project[37] and Scratch Perverts on their U.K/European tours.[38]

In 2008, Daley featured at the South by Southwest music festival in Texas[39] and in 2010 he toured the UK with Nas and Damian Marley on the "Distant Relatives" tour, which included the British rapper Ty.[40]

In November 2010, Daley embarked on his own headline tour of the UK, with 20 dates overall.[41] He was present at the "One Love:No Borders Hip Hop" event held in Birmingham, England in April 2011, with Iron Braydz from London, Lowkey, Logic and other up-and-coming UK artists.[42] In August 2012, he performed at the Outlook Festival[43] and in November 2012, he performed at the second edition of NH7 Weekender music festival in Pune, India.[44]

Writing

[edit]Natives

[edit]In May 2018, Daley published Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire. The book is part biography, and part polemic on race and class. The overall ideological framework of the book is a pragmatic, socialist-oriented Pan-Africanism that claims to seek the liberation of all humanity from oppression and exploitation. At the same time, Daley highlights what he believes are shared problems faced by African communities worldwide in what he describes as a global system of imperialism.[45]

Daley attributes his escape from poverty not to personal exceptionalism but to the vagaries and chaotic injustice of race, class and privilege.[46] Daley asserts that Britain is not a meritocracy where the barriers of race and class can be simply overcome through hard work and perseverance. He explains his success as the absurd and unexpected consequence of an unequal system that allows the rise of a few while leaving behind the many, no matter how brilliant they are. He claims several times in the book that some of his friends could have been academics or scientists if the obstacles of what he terms 'structural racism' and 'class oppression' had not been there.[47]

Visions

[edit]In 2016[48] Akala published a graphic novel/comic book called Visions. Akala's own comic deals with his interests, and references. It is a semi-autobiographical journey into magical realism, which begins with him smashing a television with a teapot, then takes us through altered states of consciousness, reincarnation, hallucinations, and themes of indigenous spiritualities and ancestral memory.

Political views

[edit]In June 2016, Daley supported Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn after mass resignations from his cabinet and a leadership challenge. He tweeted: "The way these dickhead Labour MP's [sic] are snaking @jeremycorbyn eediat ting."[49]

In May 2017, he endorsed Corbyn in the 2017 UK general election. He wrote in The Guardian: "So why will I be voting now? Jeremy Corbyn. It's not that I am naïve enough to believe that one man (who is, of course, powerless without the people that support him) can fundamentally alter the nature of British politics, or that I think that if Labour wins that the UK will suddenly reflect his personal political convictions, or even that I believe that the prime minister actually runs the country. However, for the first time in my adult life, and perhaps for the first time in British history, someone I would consider to be a fundamentally decent human being has a chance of being elected."[50]

In November 2019, along with 34 other musicians, Daley signed a letter endorsing Corbyn in the 2019 UK general election with a call to end austerity.[51][52]

Daley acknowledges institutionalised racism: "My analysis of institutionalised racism is not 'oh, this is an excuse to fail' – quite the opposite. The earlier you're aware of the hurdles, the easier they are to jump over."[11]

Lectures, speeches and interviews

[edit]Lectures

[edit]Daley has given guest lectures at East 15 Acting School, University of Essex, Manchester Metropolitan University,[53] Sydney University,[54] Sheffield Hallam University,[55] Cardiff University, and the International Slavery Museum,[56] as well as a workshop on songwriting at the School of Oriental and African Studies.[57] He has also spoken at the Oxford Union.[58] He has also been involved in campaigns to "decolonise" the curriculum including giving a talk at the University of Leicester.[59]

Activism

[edit]The Hip-hop Shakespeare Company

[edit]Founded in 2009 by Daley, The Hip-hop Shakespeare Company (THSC) is a music theatre production company aimed at exploring the social, cultural and linguistic parallels between the works of William Shakespeare and that of modern day hip-hop artists.

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]| Album Information |

|---|

It's Not a Rumour

|

Freedom Lasso

|

DoubleThink

|

The Thieves Banquet

|

Knowledge Is Power II[60]

|

Compilation

[edit]| Album Information |

|---|

10 Years of Akala[61]

|

EPs

[edit]| EP Information |

|---|

Acoustic Remixes - EP[62]

|

Visions - EP[63]

|

Mixtapes

[edit]| Mixtape Information |

|---|

The War Mixtape

|

A Little Darker (with Ms. Dynamite)

|

The War Mixtape Vol. 2

|

Knowledge Is Power Volume 1

|

Singles

[edit]- "Welcome to England" (2003)

- "War" (2004)

- "Roll Wid Us" (2005) – UK No. 72[64]

- "Bullshit" (2005)

- "The Edge" (featuring Niara) (2006)

- "Dat Boy Akala" (featuring Low Deep) (2006)

- "Shakespeare" (2006)

- "Doin' Nuffin" / "Hold Your Head Up" (2006)

- "Bit By Bit" (2007)

- "Freedom Lasso" (2007)

- "Where I'm From" (2007)

- "Comedy Tragedy History" (2008)

- "XXL" (2010)

- "Yours and My Children" (2010)

- "Find No Enemy" (2011)

- "Lose Myself" (featuring Josh Osho) (2013)

- "Mr. Fire in the Booth" (2015)

- "Giants" (featuring Kabaka Pyramid & Marshall) (2016)

Songs used in other media

[edit]- The song "Roll Wid Us", was used in the 2006 British film Kidulthood.

- The song "The Edge", from It's Not A Rumour, was used in the NBA 2K10 video game.

- The song "Shakespeare" was used on a Channel 4 advert for their Street Summer.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Akala contact information". bookingagentinfo.com. 2020.

- ^ Chris True. "Akala". AllMusic.

- ^ Mills, Kelly-Ann (25 October 2019). "Raheem Sterling joins Meghan and Stormzy in top 100 most influential black Brits". mirror. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Lavender, Jane (17 November 2020). "Lewis Hamilton ends incredible year top of influential Black Powerlist 2021". mirror. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Kate Mossman, "Akala: Dynamite by any other name...", The Observer, 2 June 2013.

- ^ Brian Rose, "Fight the Power — Akala and the Power of the Word" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, London Real Academy, 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Natives". Socialist Review. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Akala: 'As I grew up, I became embarrassed by my mother's whiteness'". The Guardian. 26 May 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Akala's race polemic nominated for James Tait Black literary prize | Scotland". The Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Akala biography". Last.fm. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Subashini, Dr (3 April 2019). "Akala: "I don't enjoy explaining that black people are human beings"". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Akala receives honorary doctorate | The Voice Online". Archive.voice-online.co.uk. 24 June 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Spoilt for choice". Sky Sports. 16 February 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Akala". Brighton.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

He told graduates: "I can't lie, I often envy those of you who do get to go, people like you … who are about to remake the world, or at least this country. That's how serious these four years are. What will you do with the time you spent here and the education you have been privileged to be loaned by the rest of society?

- ^ siriusgibson (27 September 2018). "Video: Akala's graduation speech". The magazine for Oxford Brookes alumni, supporters and friends. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Bastable, Bex (27 July 2018). "Albion boss to receive honorary doctorate from Brighton University". Brighton & Hove Independent. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Akala interview on "The Situation" website". Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ "Akala (2) - The War Mixtape". Discogs. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Webb, Adam. "BBC - Music - Review of Akala - It's Not a Rumour". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "MOBO Awards 2006 | MOBO Organisation". www.mobo.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Akala (2) & Ms. Dynamite - A Little Darker EP". Discogs. 2006.

- ^ "BBC Two - Shakespeare Live! From the RSC - Akala". BBC. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Macpherson, Alex (27 September 2007). "CD: Akala, Freedom Lasso". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Akala Releases His Long Awaited Mixtape Entitled The War Mixtape Vol 2". Top40-Charts.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Akala: Doublethink Interview (video)". The Orwell Foundation. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Andrews, Charlotte Richardson (9 July 2014). "Brit-hop: 10 of the best". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Love, Emma (26 November 2010). "Hip-hop deciphered at the British Library". The Independent. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Evolving English One Language Many Voices80". The British Library. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Akala – Fire in the Booth Part 2". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ Ali, Syed Hamad (19 September 2013). "English rapper Akala unplugged". gulfnews.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Akala". BBC. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Interview:Akala". The National Student. BigChoiceGroup Ltd. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ DBarry. "Top British rapper Akala performs workshops on Darling Downs". Daily Mercury. NewsCorp, The Mackay Printing and Publishing Company Pty Ltd. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Richard Ashcroft Online : Biography". www.richardashcroftonline.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Audio Bullys + Akala (De Zwerver)". Out.be (in French). Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "DJ Shadow + Akala + Stateless @ Brixton Academy, London | Live Music Reviews". musicOMH. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Gotan Project @ Brixton Academy, London | Live Music Reviews". musicOMH. 3 November 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Pistols, Dub. "Award winning hip hop artist Akala joins Dub Pistols in the studio". Dub Pistols. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Savlov, Marc. "How the West Was Won". www.austinchronicle.com. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "UK Music News: Ty and Akala Official Support Acts for Nas and Damien Marley 'distant Relatives' UK Tour". MAD NEWS UK. 31 May 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Pledger, Paul. "UK grime rapper Akala announces an XXL live tour for November 2010 and new album". Allgigs. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "March 30, 2011". Daily Urban Newz. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Outlook Festival 2012". Clash Magazine. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Singh, Nirmika (1 November 2012). "Rapper Akala combines Shakespearean verses and sonnets". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Book review: Akala - Natives - Invent the FutureInvent the Future". Invent-the-future.org. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ David Olusoga. "Natives by Akala review – the hip-hop artist on race and class in the ruins of empire | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Natives". Socialist Review. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ lovereading4kids.co.uk. "Books By Akala - Author". lovereading4kids.co.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The way these dickhead Labor MP's are snaking @jeremycorbyn eediat ting". Twitter. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "By choice, I've never voted before. But Jeremy Corbyn has changed my mind". The Guardian. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Musicians backing Jeremy Corbyn's Labour". The Guardian. 25 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Gayle, Damien (25 November 2019). "Stormzy backs Labour in election with call to end austerity". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ "Bringing hip hop to the lecture theatre". Manchester Metropolitan University. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Akala and Artists in conversation". Sydney University. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "From hip-hop theatre to lecture theatre". Sheffield Hallam University. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Slavery Remembrance Day 2016 talk". National Museums Liverpool. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ "SOAS Writing Week". School of Oriental and African Studies. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Akala, Full Address and Q&A, Oxford Union". Oxford Union official YouTube channel. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Decolonising Our Curriculum With AKALA | Leicester Info". interests.me. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Knowledge Is Power, Vol. 2". iTunes. 30 March 2015.

- ^ "10 Years of Akala". iTunes. 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Acoustic Remixes - EP". iTunes. 13 October 2008.

- ^ "Visions - EP". iTunes. 28 July 2017.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 18. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

External links

[edit]- 1983 births

- Living people

- British anti-racism activists

- Black British male rappers

- English people of Jamaican descent

- Labour Party (UK) people

- People from Kentish Town

- Political music artists

- Rappers from the London Borough of Camden

- English people of Scottish descent

- Writers from the London Borough of Camden