Mahmud Barzanji

| Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji شێخ مهحموود | |

|---|---|

| Şêx Mehmûdê Berzencî Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji[1] | |

| |

| King of Kurdistan | |

| Reign | September 1921 - July 1924 |

| Predecessor | Office established |

| Born | 1878 Sulaymaniyah, Mosul Vilayet, Ottoman Iraq, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 9 October 1956 (aged 77–78) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Burial | Sulaymaniyah, Iraqi Kurdistan, Iraq |

| Issue | Baba Ali Shaikh Mahmood (son, 1912–1996) |

| Rebellious leader | |

| Allegiance | Azadî - Society for the Rise of Kurdistan |

| Service | Barzanji Battalion |

| Battles / wars | |

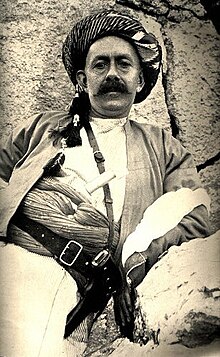

Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji, also known as Mahmud Hafid Zadeh (1878 in Sulaymaniyah – October 9, 1956 in Baghdad) was a Kurdish leader of a series of Kurdish uprisings against the British Mandate of Iraq.[2] He was sheikh of a Qadiriyah Sufi family of the Barzanji clan from the city of Sulaymaniyah, which is now in Iraqi Kurdistan. He was named King of Kurdistan during several of these uprisings.[2]

When the British Mandate of Mesopotamia was established in what is now Iraq after World War I, the British sought a suitable means of governing the Kurdish north. In 1918, following the tribal government in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of what is now Pakistan, then part of British India, the British appointed Barzaniji as governor over the Kurds in Sulaimaniyah.[3] However, the determination of Barzanji was not in the interests of all Kurds, as the rivalry between tribes and orders was great.[4]

Early life and descent

[edit]Mahmud Barzanji was born 1878 in Sulaymaniyah as the son of parents who belonged to the Barzanji clan. Barzanji‘s family also were Sufi Qadiriyya, of which he later became sheikh.[5] Sheikh Mahmud was also appointed Governor of the former sanjak of Duhok from 1911 to 1919.[6]

Political commitment

[edit]

First struggles with Ottoman politics

[edit]The Kurdish nationalist struggle first emerged in the late 19th century when a unified movement demanded the establishment of a Kurdish state. Revolts occurred sporadically, but only decades after the Ottoman centralist policies of the 19th century began did the first modern Kurdish nationalist movement emerge with an uprising led by a Kurdish landowner and head of the powerful Shemdinan family, Sheikh Ubeydullah.[7] In 1880 Ubeydullah demanded political autonomy or outright independence for Kurds and the recognition of a Kurdistan state without interference from Turkish or Persian authorities."[8] The uprising against Qajar Persia and the Ottoman Empire was ultimately suppressed by the Ottomans, and Ubeydullah, along with Sheikh Mahmud and other notables, was exiled to Istanbul.[9] After World War I, the British and other Western powers occupied parts of the Ottoman Empire. Plans made with the French in the Sykes–Picot Agreement designated Britain as the mandate power.[10] The British were able to form their own borders to their pleasure to gain an advantage in this region.[11] The British had firm control of Baghdad and Basra and the regions around these cities mostly consisted of Shiite and Sunni Arabs.[12] Western powers (particularly the United Kingdom) fighting the Turks promised the Kurdish tribal leaders (under them Sheikh Mahmud) that they would act as guarantors for Kurdish freedom,[13] a promise they subsequently broke.[14] One particular organization, the Society for the Elevation of Kurdistan (Kürdistan Teali Cemiyeti) was central to the forging of a distinct Kurdish identity. It took advantage of period of political liberalization in during the Second Constitutional Era (1908–1920) of Turkey to transform a renewed interest in Kurdish culture and language into a political nationalist movement based on ethnicity.[9] Around the start of the 20th century Russian anthropologists encouraged this emphasis on Kurds as a distinct ethnicity, suggesting that the Kurds were a European race (compared to the Asiatic Turks) based on physical characteristics and on the Kurdish language (which forms part of the Indo-European language-group).[15] While these researchers had ulterior political motives (to sow dissent in the Ottoman Empire) their findings were embraced and still accepted today by many.[16][17]

Strivings for an independent Kurdish state

[edit]In 1921, the British appointed Faisal I the King of Iraq. It was an interesting choice because Faisal had no local connections, as he was part of the Hashemite family in Western Arabia.[18] As events were unfolding in the southern part of Iraq, the British were also developing new policies in northern Iraq, which was primarily inhabited by Kurds, and was known as Greater Kurdistan in the Paris (Versailles) Peace Conference of 1919. The borders that the British formed had the Kurds between central Iraq (Baghdad) and the Ottoman lands of the north.

The Kurdish people of Iraq lived in the mountainous and terrain of the Mosul Vilayet. It was a difficult region to control from the British perspective because of the terrain and tribal loyalties of the Kurds. There was much conflict after the Great War between the Ottoman government and British on how the borders should be established. The Ottomans were unhappy with the outcome of the Treaty of Sèvres, which allowed the Great War victors control over much of the former Ottoman lands through the distribution of formerly Ottoman territory as League of Nations mandates.

In particular, the Turks felt that the Mosul Vilayet was theirs because the British had illegally conquered it after the Mudros Armistice, which had ended hostilities in the war.[19] With the discovery of oil in northern Iraq, the British were unwilling to relinquish the Mosul Vilayet.[20] Also, it was to the British advantage to have the Kurds play a buffer role between themselves and the Ottoman Empire. All that led to the importance of Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji.

The British government promised the Kurds during the First World War that they would receive their own land to form a Kurdish state. However, the British government did not keep their promise at the end of the war, leading to resentment among the Kurds.[21] There was mistrust on the part of the Kurds. In 1919, uneasiness began to evolve in the Kurdish regions because they were unhappy with their current situation and in their dealings with the British government. The Kurds revolted a year later.

The British government attempted to establish a Kurdish protectorate in the region and so appointed a popular leader of the region,[22] which was how Mahmud became governor of southern Kurdistan.

Mahmud was a very ambitious Kurdish national leader and promoted the idea of Kurds controlling their own state and gaining independence from the British. As Charles Tripp relates, the British appointed him governor of Sulaimaniah in southern Kurdistan as a way of gaining an indirect rule in this region. The British wanted this indirect rule with the popular Mahmud at the helm, which they believed would give them a face and a leader to control and calm the region. However, with a little taste of power, Mahmud had ambitions for more for himself and for the Kurdish people. He was declared "King of Kurdistan" and claimed to be the ruler of all Kurds, but the opinion of Mahmud among Kurds was mixed because he was becoming too powerful and ambitious for some.[23]

Mahmud hoped to create Kurdistan and initially the British allowed Mahmud to pursue has ambitions because he was bringing the region and people together under indirect British control. However, by 1920 Mahmud, to British displeasure, was using his power against the British by arresting British officials in the Kurd region and starting uprisings against the British.[24] As historian Kevin McKierman writes, "The rebellion lasted until Mahmud was wounded in combat, which occurred on the road between Kirkuk and Sulaimaniah. Captured by British forces, he was sentenced to death but later imprisoned in a British fort in Lahore."[25] Mahmud remained in India until 1922.

Rise to power

[edit]

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in October 1918, Barzanji sought to break away from the Ottomans and create an autonomous southern Kurdistan under British supervision. He was elected as the head of government by a council of Kurdish notables in the Sulaimaniya region, and as soon as the British captured Kirkuk (25 October 1918[26]) he captured Ottoman troops present in his district and declared the end of Ottoman rule, pledging allegiance to Britain. Other Kurdish regions followed suit, such as Rania and Keuisenjaq.[27]

The Ottoman position was that the region was still legally under their rule, despite the armistice. (Further information: Mosul Question) They did not recognize the Kurdish state. In contrast, British officials on the ground chose to accept Kurdish cooperation, despite officially lacking a well-defined policy on southern Kurdistan.[27]

Mahmud Barzanji was designated by the British as governor of Kurdish area B, which extended from south of the Lesser Zab River to the old Ottoman-Persian frontier.[28] Barzanji attempted to expand his influence outside his designated region, and used British subsidies, provided for salaries and to assist recovery from the ravages of war, in order to consolidate his power base, buying the loyalty of chieftains.[28] This led to deteriorating relations with the British, setting the stage for an eventual revolt.[28]

On 23 May 1919, a few months after being appointed governor of Sulaymaniyah, Barzanji raised 300 tribal fighters, expelled British supervisors and proclaimed himself "Ruler of all Kurdistan", initiating the first of the Mahmud Barzanji revolts.[29] Early in the rebellion, the Kurds saw some success with the successful ambush of a light British column that strayed beyond Chamchamal. On both sides of the border, tribes proclaimed themselves for Shaykh Mahmud.[29]

British involvement was restricted to a role of supervision, and the local government retained autonomy in regards to matters relating to judiciary and revenue.[30] Edward Noel was appointed by Arnold Wilson as political officer responsible for supervision.[30]

Tribal fighters from both Iran and Iraq quickly allied themselves with Sheykh Mahmud as he became more successful in opposing British rule. According to McDowall, the Sheykh's forces "were largely Barzinja tenantry and tribesmen, the Hamavand under Karim Fattah Beg, and disaffected sections of the Jaf, Jabbari, Sheykh Bizayni and Shuan tribes".[31]

Among the supporters of Sheykh Mahmud was also the 16-year-old Mustafa Barzani, who was to become the future leader of the Kurdish nationalist cause and a commander of the Peshmerga forces. Barzani and his men, following the orders of Barzani tribal Shekyh Ahmed Barzani, crossed the Piyaw Valley to join Sheykh Mahmud Barzanji. Even though they were ambushed several times on the way, Barzani and his men managed to reach Sheykh Mahmud's location, however were too late to aid the revolt.[32] The Barzani fighters were only a part of the Sheykh's 500-person force.

As the British became aware of the sheykh's growing political and military power, they were forced to respond militarily, and two brigades defeated the 500-strong Kurdish force in the Bazyan Pass[33] on 18 June, and occupied Halabja on the 28th, ending the Kurdish state and defeating the rebellion.[34][35]

Sheykh Mahmud's exile

[edit]Sheykh Mahmud Barzanji was arrested and sent into exile to India in 1921.[36] Mahmud's fighters continued to oppose British rule after his arrest. Although no longer organized under one leader, this intertribal force was "actively anti-British", engaging in hit-and-run attacks, killing British military officers, and participating in another – left the Turkish ranks to join the Kurdish army.[37]

Return and second revolt

[edit]

With the exile of the Sheikh in India, Turkish nationalists in the crumbling Ottoman Empire were causing a great deal of trouble in the Kurdish regions of Iraq. The Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal, were riding high in the early 1920s after their victory against Greece and were looking to take that momentum into Iraq and take back Mosul which began the Mosul question. With the British in direct control of northern Iraq after the exile of Sheikh Mahmud, the area was becoming increasingly hostile for the British officials due to the threat from Turkey. The region was led by the Sheikh's brother, Sheikh Qadir, who was not capable of handling the situation and was seen by the British as an unstable and unreliable leader.

Sir Percy Cox, a British military official and administrator to the Middle East especially Iraq, and Winston Churchill, a British politician, were at odds on whether to release the Sheikh from his exile and bring him back to reign in northern Iraq. That would allow the British to have better control over the hostile but important region. Cox argued that the British could gain authority in a region they recently evacuated, and the Sheikh was the only hope of gaining back a stable region.[38] Cox was aware of the dangers of bringing back the Sheikh, but he was also aware that one of the main reasons for the unrest in the region was the growing perception that the earlier promises of autonomy would be abandoned and the British would bring the Kurdish people under direct rule of the Arab government in Baghdad. The Kurdish dream of an independent state was growing less likely which caused conflict in the region.[39] Bringing the Sheikh back was their only chance of a peaceful Iraqi state in the region and against Turkey.

Cox agreed to bring back the Sheikh and name him governor of southern Kurdistan. On December 20, 1922, Cox also agreed to a joint Anglo-Iraqi declaration that would allow a Kurdish government if they were able to form a constitution and agree on boundaries. Cox knew that with the instability in the region and the fact that there were many Kurdish groups it would be nearly impossible for them to come to a solution.[40] Upon his return, Mahmud proceeded to pronounce himself King of the Kingdom of Kurdistan. The Sheikh rejected the deal with the British and began working in alliance with the Turks against the British. Cox realized the situation and in 1923 he denied the Kurds any say in the Iraqi government and withdrew his offer of their own independent state. The Sheikh was the king until 1924 and was involved in uprisings against the British until 1932, when the Royal Air Force and British-trained Iraqis were able to capture the Sheikh again and exile him to southern Iraq.[40][41]

Sheikh Mahmud resigned signed a peace accord with the new Iraqi government, returning from the underground to the independent Iraq in 1932.[42]

World War II

[edit]In May 1941, Barzanji staged a brief revolt in northern Iraq after the Rashid Ali coup of April 1941 before the British eventually occupied Sulaymaniyah on 6 June 1941. He hoped that the British would grant him an independent Kurdistan, but this never culminated.[43]

Death and legacy

[edit]He ultimately died in 1956 with his family. He is still remembered today with displays of him around Iraqi Kurdistan and especially in Sulaimaniah. He is a hero to the Kurdish people to this day, as he is thought of as an pioneering Kurdish nationalist who fought for the independence and respect of his people.[44] He is regarded as a pioneer for many future Kurd leaders.[45]

An academic source published by the University of Cambridge has stated: "Kurdish nationalists in the diaspora, as long-distance nationalist actors, have played a crucial role in the development of Kurdish nationalism both inside and outside the region. They strongly hold on to a Kurdish identity and promote the territoriality of this unified nation in which one of their motives is Sheikh Mahmuds personality and reachments. In line with the contemporary international normative framework, they use the rhetoric of suffering, the incidents of human rights abuses and their right to statehood to influence the way host states, other states, international organizations, scholars, journalists and the international media perceive their case and the actions of their home states. They promote the idea that Kurdistan is one country artificially divided among regional states and that this dividedness is the source of Kurdish suffering."[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sicker, Martin (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275968939.

- ^ a b Dana, Charles A.; Dunn, Joe P. (2015). "A Death in Dohuk: Roger C. Cumberland, Mission and Politics Among the Kurds in Northern Iraq, 1923-1938". Journal of Third World Studies. 32 (1): 245–271. ISSN 8755-3449. JSTOR 45178577.

- ^ Dockstader, Jason; Mûkrîyan, Rojîn (2022). "Kurdish liberty". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 48 (8): 1174–1196. doi:10.1177/01914537211040250.

- ^ Natali, Denise (2004). "Ottoman Kurds and emergent Kurdish nationalism". Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 13 (3): 383–387. doi:10.1080/1066992042000300701. S2CID 220375529.

- ^ Eskander, Saad (2000). "Britain's Policy in Southern Kurdistan: The Formation and the Termination of the First Kurdish Government, 1918–1919". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (2): 139–163. doi:10.1080/13530190020000501. S2CID 144862193.

- ^ Eskander, Saad (2000). "Britain's Policy in Southern Kurdistan: The Formation and the Termination of the First Kurdish Government, 1918–1919". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (2): 139–163. doi:10.1080/13530190020000501. S2CID 144862193.

- ^ Natali 2005, p. 6

- ^ Ozoglu, Hakan. Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries. Feb 2004. ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5. Pg 75.

- ^ a b Natali, Denise (2004). "Ottoman Kurds and emergent Kurdish nationalism". Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 13 (3): 383–387. doi:10.1080/1066992042000300701. S2CID 220375529.

- ^ Fromkin, David (1 September 2001). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. Henry Holt and Company.

- ^ BBC (25 April 2018). "Iraqi Kurdistan profile". BBC News.

- ^ Natali 2005, p. 26

- ^ Dockstader, Jason; Mûkrîyan, Rojîn (2022). "Kurdish liberty". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 48 (8): 1174–1196. doi:10.1177/01914537211040250.

- ^ Natali 2005, p. 26

- ^ Laçiner, Bal; Bal, Ihsan. "The Ideological And Historical Roots Of Kurdist Movements In Turkey: Ethnicity Demography, Politics". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 10 (3): 473–504. doi:10.1080/13537110490518282. S2CID 144607707. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Natali 2005, p. 14

- ^ Natali 2005, p. 9

- ^ Hashemites Family. "Hashemites". www.alhussein.jo.

- ^ Oltoman Empire. "The Mosul Vilayet". www.researchgate.net.

- ^ Hale, William M. (2000). Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774-2000. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780714650715.

- ^ World WAR I. "BRITISH LIES IN THE WORLD WAR I". www.worldfuturefund.org.

- ^ İki Hükümet Bir Teşkilat. "History" (PDF). www.historystudies.net.

- ^ Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq. Cambridge Press, 2007. Page 33-34

- ^ Lortz, Michael. "The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga"[permanent dead link], Willing to face Death: A History of Kurdish Military Forces - the Peshmerga - from the Ottoman Empire to Present-Day Iraq, 2005-10-28. Pages 10–11

- ^ McKierman, Kevin. The Kurds. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006. Page 31

- ^ Moberly, James (1927). HISTORY OF THE GREAT WAR BASED ON OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS. THE CAMPAIGN IN MESOPOTAMIA 1914-1918. Vol. 4. His Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 276.

- ^ a b Eskander, Saad. "Britain's Policy Towards The Kurdish Question, 1915-1923" (PDF). etheses.lse.ac.uk. pp. 49–57, 182.

- ^ a b c McDowall, David (1997). A Modern History of the Kurds. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-1-86064-185-5.

- ^ a b McDowall, David (1997). A Modern History of the Kurds. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 155–160. ISBN 978-1-86064-185-5.

- ^ a b Eskander, Saad. "Britain's Policy Towards The Kurdish Question, 1915-1923" (PDF). etheses.lse.ac.uk. pp. 49–57, 182.

- ^ McDowall, David (2007) [1996]. "The Kurds, Britain and Iraq". A Modern History of the Kurds (3rd ed.). I.B. Tauris. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0.

- ^ Lortz, Michael G. (2005). "Chapter 1: Introduction: The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga" (PDF). Willing to Face Death: A History of Kurdish Military Forces — the Peshmerga — from the Ottoman Empire to Present-Day Iraq (Thesis). Florida State University. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ McDowall, David (1997). A Modern History of the Kurds. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 155–160. ISBN 978-1-86064-185-5.

- ^ Kilic, Ilhan (2018). Britain's Kurdish Policy and Kurdistan 1918 -1923 (PDF). School of History of the University of East Anglia. pp. 182–183.

- ^ Eskander, Saad. "Britain's Policy Towards The Kurdish Question, 1915-1923" (PDF). etheses.lse.ac.uk. p. 55.

In summer 1919, this state was disposed of, after the British suppressed a Kurdish rebellion.

- ^ Lortz, Michael G. (2005). "Chapter 1: Introduction: The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga" (PDF). Willing to Face Death: A History of Kurdish Military Forces — the Peshmerga — from the Ottoman Empire to Present-Day Iraq (Thesis). Florida State University. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Prince, J. (1993), "A Kurdish State in Iraq" in Current History, January.

- ^ Olson, Robert. The Emergence of Kurdish Nationalist and the Sheikh Sa'id Rebellion, 1880–1925. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989. Pages 60–61

- ^ Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq. Cambridge Press, 2007. Page 53

- ^ a b McKierman, Kevin. The Kurds. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006. Page 32

- ^ Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq. Cambridge Press, 2007. Page 66

- ^ Lortz, Michael G. (2005). "Chapter 1: Introduction: The Kurdish Warrior Tradition and the Importance of the Peshmerga" (PDF). Willing to Face Death: A History of Kurdish Military Forces — the Peshmerga — from the Ottoman Empire to Present-Day Iraq (Thesis). Florida State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Disney, Jr., Donald Bruce. "THE KURDISH NATIONALIST MOVEMENT AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES," (PDF). apps.dtic.mil. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-06-16. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ "Kurdish People Fast Facts". CNN Library.

- ^ Nakhoul, Samia. "Iraqi Kurdish leader says no turning back on independence bid". U.S.

- ^ Kaya, Zeynep N. (2020). Mapping Kurdistan: Territory, Self-Determination and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-108-47469-6.

Sources

[edit]- Natali, Denise (2005). The Kurds and the State: Evolving National Identity in Iraq, Turkey, And Iran. NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3084-5.

- Özoğlu, Hakan (2004). Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5.

- Schaller, Dominik J.; Zimmerer, Jürgen (March 2008), "Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies—introduction", Journal of Genocide Research, 10 (1): 7–14, doi:10.1080/14623520801950820, S2CID 71515470

External links

[edit]- Ethnic Cleansing and the Kurds

- The Rebellion of Sheikh Mahmmud Barzanji, in German

- The Kingdom of Kurdistan

- Footnotes to History (Kurdistan, Kingdom of)

- Sheik Mahmmud Barzanji