Israel Kamakawiwoʻole

Israel Kamakawiwoʻole | |

|---|---|

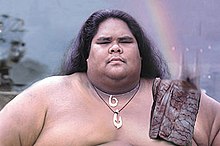

Kamakawiwoʻole in 1993 | |

| Born | Israel Kaʻanoʻi Kamakawiwoʻole May 20, 1959 Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, U.S. |

| Died | June 26, 1997 (aged 38) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1976-1997 |

| Children | 1 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | Mountain Apple Company |

Israel Kaʻanoʻi Kamakawiwoʻole[a] (May 20, 1959 – June 26, 1997), also called Braddah IZ or just simply IZ, was a Native Hawaiian musician and singer. He achieved commercial success and popularity outside of Hawaii with his 1993 studio album, Facing Future. His medley of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World" was released on his albums Ka ʻAnoʻi and Facing Future, and was subsequently featured in various media. The song has had 358 weeks on top of the World Digital Songs chart, making it the longest-leading number-one hit on any of the Billboard song charts. Kamakawiwoʻole is regarded as one of the greatest musicians from Hawaii and is the most successful musician from the state.[2][3]

Along with his ukulele playing and incorporation of other genres, such as jazz and reggae, Kamakawiwoʻole remains influential on Hawaiian music.[4] He was named "The Voice of Hawai‘i" by NPR in 2010.[5]

Early life

[edit]Israel Kaʻanoʻi Kamakawiwoʻole was born at Kuakini Medical Center on May 20, 1959, in Honolulu to Henry "Hank" Kaleialoha Naniwa Kamakawiwoʻole Jr. and Evangeline "Angie" Leinani Kamakawiwoʻole, who worked at a popular Waikiki nightclub. His mother was the manager while his father was a bouncer; his father also drove a sanitation truck at the U.S. Navy shipyard at Pearl Harbor.[6] The notable Hawaiian musician Moe Keale was Kamakawiwoʻole's uncle and a major musical influence. Kamakawiwoʻole was raised in the community of Kaimuki, where his parents had met and married.

Kamakawiwoʻole began playing music with his older brother, Henry Kaleialoha Naniwa Kamakawiwoʻole III ("Skippy"), and cousin Allen Thornton, at age 11 after being exposed to the music of Hawaiian entertainers of the time such as Peter Moon, Palani Vaughan, Keola Beamer and Don Ho, who frequented the establishment where Kamakawiwoʻole's parents worked. Hawaiian musician Del Beazley spoke of the first time he heard Kamakawiwoʻole perform, when, while playing for a graduation party, the whole room fell silent on hearing him sing.[7] Kamakawiwoʻole remained in Hawaii as his brother Skippy entered the Army in 1971 and his cousin Allen moved to the mainland in 1976.

In his early teens, Kamakawiwoʻole studied at Upward Bound (UB) of the University of Hawaii at Hilo and his family moved to Mākaha. There, Kamakawiwoʻole met Louis Kauakahi, Sam Gray, and Jerome Koko.[8] Together with Skippy, they formed the Makaha Sons of Niʻihau. A part of the Hawaiian Renaissance, the band's blend of contemporary and traditional styles gained in popularity as they toured Hawaii and the mainland United States, releasing fifteen successful albums. Kamakawiwoʻole's aim was to make music that stayed true to the typical sound of traditional Hawaiian music. His cousin Bill Keale is also a musician.

Music career

[edit]The Makaha Sons of Niʻihau recorded No Kristo in 1976 and released several more albums, including Hoʻoluana, Kahea O Keale, Keala, Makaha Sons of Niʻihau and Mahalo Ke Akua.

The group became Hawaii's most popular contemporary traditional group with breakout albums 1984's Puana Hou Me Ke Aloha and its follow-up, 1986's Hoʻola. Kamakawiwoʻole's last recorded album with the group was 1991's Hoʻoluana. It remains the group's top-selling CD.[citation needed] In 1982, Skippy died at age 28 of a heart attack.[9] Later that year, Kamakawiwoʻole married his childhood sweetheart Marlene. They had a daughter named Ceslie-Ann "Wehi" Kamakawiwoʻole (born c. 1983).

In 1990, Kamakawiwoʻole released his first solo album Ka ʻAnoʻi, which won awards for Contemporary Album of the Year and Male Vocalist of the Year from the Hawaiʻi Academy of Recording Arts (HARA). Facing Future was released in 1993 by The Mountain Apple Company. It featured a version of his most popular song, the medley "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World" (listed as "Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World"), along with "Hawaiʻi '78", "White Sandy Beach", "Maui Hawaiian Sup'pa Man", and "Kaulana Kawaihae". The decision to include a cover of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" was said to be a last-minute one by Kamakawiwoʻole's producer Jon de Mello and Kamakawiwoʻole.[10] Facing Future debuted at No. 25 on Billboard magazine's Top Pop Catalogue chart. On October 26, 2005, Facing Future became Hawaiʻi's first certified platinum album, selling more than a million CDs in the United States, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.[11] On July 21, 2006, BBC Radio 1 announced that "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World (True Dreams)" would be released as a single in America.

In 1994, Kamakawiwoʻole was voted favorite entertainer of the year by the Hawaiʻi Academy of Recording Arts (HARA). E Ala E (1995) featured the political title song "ʻE Ala ʻE" and "Kaleohano", and N Dis Life (1996) featured "In This Life" and "Starting All Over Again".

In 1997, Kamakawiwoʻole was again honored by HARA at the annual Na Hoku Hanohano Awards for Male Vocalist of the Year, Favorite Entertainer of the Year, Album of the Year, and Island Contemporary Album of the Year. He watched the awards ceremony from a hospital room.

The posthumously released album Alone in Iz World (2001) debuted at No. 1 on Billboard's World Chart and No. 135 on Billboard's Top 200, No. 13 on the Top Independent Albums Chart, and No. 15 on the Top Internet Album Sales charts. In November 2012, Honolulu magazine ranked it as the third-greatest Hawaii album of the 21st century.[12]

Kamakawiwoʻole's album Facing Future was the first Hawaii album to be certified gold.[13]

Support of Hawaiian rights

[edit]Kamakawiwoʻole was known for promoting Hawaiian rights and Hawaiian independence, both through his lyrics, which often stated the case for independence directly and through his own actions.[14] For example, the lyric in his song "Hawaiʻi '78": "The life of this land is the life of the people/and that to care for the land (malama ʻāina) is to care for the Hawaiian culture", is a statement that many consider summarizing his Hawaiian ideals.[15] The state motto of Hawaiʻi is a recurring line in the song and encompasses the meaning of his message: "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono" (proclaimed by King Kamehameha III when Hawaiʻi regained sovereignty in 1843. It can be roughly translated as: "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness").[16]

Kamakawiwoʻole used his music to promote awareness of his belief that a second-class status had been pushed onto fellow natives by the tourism industry.[17]

Later life

[edit]In the 1990s, Kamakawiwoʻole became a born-again Christian. In 1996, he was baptized at the Word of Life Christian Center in Honolulu and spoke publicly about his beliefs at the Na Hoku Hanohano Awards. Kamakawiwoʻole also recorded the song "Ke Alo O Iesu" (Hawaiian: The Presence of Jesus).[18]

Death

[edit]Kamakawiwoʻole struggled with obesity throughout his life,[19] at one point weighing 757 pounds (343 kg) while standing 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) tall.[20] Kamakawiwoʻole endured several hospitalizations because of his weight.[20] With chronic medical problems including respiratory and cardiac issues, Kamakawiwoʻole died at age 38 in the Queen's Medical Center in Honolulu at 12:18 a.m. on June 26, 1997, from respiratory failure.[20]

On July 10, 1997, the Hawaiian flag flew at half-staff for Kamakawiwoʻole's funeral. His koa wood casket lay at the state capitol building in Honolulu, making him the third person (and the only non-government official) to be so honored. Approximately 10,000 people attended his funeral. Thousands of fans gathered as his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean at Mākua Beach on July 12.[21] According to witnesses, many people commemorated him by honking their car and truck horns on all Hawaiian highways that day. Scenes from the funeral and scattering of Kamakawiwoʻole's ashes were featured in official music videos of "Over the Rainbow", released posthumously by Mountain Apple Company. As of June 2024[update], the two official video uploads of the song, as featured on YouTube by Mountain Apple Company Inc, have collectively received over 1.56 billion views.[22][23]

On September 20, 2003, hundreds paid tribute to Kamakawiwoʻole as a bronze bust of him was unveiled at the Waianae Neighborhood Community Center on Oʻahu. His widow, Marlene Kamakawiwoʻole, and sculptor Jan-Michelle Sawyer were present for the dedication ceremony.[24]

Legacy

[edit]On December 6, 2010, NPR named Kamakawiwoʻole as "The Voice of Hawaii" in its 50 great voices series.[7]

On March 24, 2011, Kamakawiwoʻole was honored with the German national music award Echo. The music managers Wolfgang Boss and Jon de Mello accepted the trophy in his stead.[25]

A 2014 Pixar short film, Lava, features two volcanoes as the main characters. Kamakawiwoʻole's cover of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and his style of music were James Ford Murphy's partial inspiration for the short film.[26]

On May 20, 2020, Google Doodle published a page in celebration of Kamakawiwoʻole's 61st birthday. It featured information about his life, musical career, and impact on Hawaii. Included was a two-minute cartoon video with Kamakawiwoʻole's cover of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" playing as the background and imagery of Hawaii. The section of the page explaining the inspiration of the Doodle says that "The Doodle is full of places in Hawaiʻi that had special significance for Israel: the sunrise at Diamond Head, Mākaha Beach, the Palehua vista, the flowing lava and volcanic landscape of the Big Island, the black sand beach at Kalapana and the Waiʻanae coast."[27]

"Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World"

[edit]Kamakawiwoʻole's recording of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World" gained notice in 1999 when an excerpt was used in the TV commercials for eToys.com (later part of Toys "R" Us). The full song was featured in the movies K-Pax, Meet Joe Black, Finding Forrester, Son of the Mask, 50 First Dates, Fred Claus, Letters to Santa and IMAX: Hubble 3D.[28] It was also featured in TV series ER, Between The Lions, Scrubs, Cold Case, Glee, South Pacific, Lost, Storm Chasers, the UK original version of Life on Mars, and in Modern Family, among others.[29]

In 1988, a friend of Kamakawiwoʻole called a Honolulu recording studio owned by Milan Bertosa at 3:00 a.m. with a request that Kamakawiwoʻole be allowed to come in to make a recording. Bertosa was about to shut down, but told the friend that Kamakawiwoʻole could come if he was able to make it within 15 minutes. In a 2011 interview, Bertosa recalled, "In walks the largest human being I had seen in my life. Israel was probably like 500 pounds. And the first thing at hand is to find something for him to sit on." A security guard gave Kamakawiwoʻole a large steel chair. "Then I put up some microphones, do a quick sound check, roll tape, and the first thing he does is 'Somewhere Over the Rainbow.' He played and sang, one take, and it was over."[7] Five years later, Bertosa was working as an engineer at Mountain Apple Company when Iz was making a solo album there. Bertosa remembered the old demo tape and introduced it to de Mello, who remarked: "Israel was really sparkly, really alive." The original 1988 acoustic version of the song was released with the 1993 Facing Future album.[30]

"Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World" reached No. 12 on Billboard's Hot Digital Tracks chart the week of January 31, 2004 (for the survey week ending January 18, 2004). It had passed two million paid downloads in the US by September 27, 2009, and then sold three million in the U.S. as of October 2, 2011.[31] And, as of October 2014, the song has sold more than 4.2 million digital copies.[32] The song is the longest-leading number-one hit on any of the Billboard song charts, having spent 358 weeks on top of the World Digital Songs chart.[33]

On July 8, 2007, Kamakawiwoʻole debuted at No. 44 on the Billboard Top 200 Album Chart with "Wonderful World", selling 17,000 units.[34]

In April 2007, "Over the Rainbow" entered the UK charts at No. 68, and eventually climbed to No. 46, spending ten weeks in the Top 100 over a two-year period.

In October 2010, following its use in a trailer for the TV channel VOX[35] and on a TV advertisement—for Axe deodorant (which is itself a revival of the advertisement originally aired in 2004)[36]—it hit No. 1 on the German singles chart, was the number-one seller single of 2010[37] and was eventually certified 2× Platinum in 2011.[38]

As of November 1, 2010, "Over the Rainbow" peaked at No. 6 on the OE3 Austria charts, which largely reflects airplay on Austria's government-operated Top 40 radio network.[39] It also peaked at No.1 in France and Switzerland in late December 2010.

On December 21, 2020, the official music video for "Over the Rainbow" reached a billion views on YouTube.[40]

In 2021, the song was inducted into the National Recording Registry as part of the heritage in American recorded sound.[41]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Ka ʻAnoʻi (1990)

- Facing Future (1993)

- E Ala E (1995)

- N Dis Life (1996)

Compilation albums

[edit]- IZ in Concert: The Man and His Music (1998)

- Alone in IZ World (2001)

- Wonderful World (2007)

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: The Best of Israel Kamakawiwoʻole (2011)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hawaiian pronunciation: [kəˌmɐkəˌvivoˈʔole]; meaning 'the fearless eye, the bold face'[1]

References

[edit]- ^ "Biography". The Official Site of Israel IZ Kamakawiwo`ole – This is the place for everything IZ Music, Stories, Videos. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "18 Of The Greatest And Most Famous Musicians From Hawaii". February 6, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ West, Macey (April 11, 2023). "20 Famous Musicians From Hawaii - Singersroom.com". Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Gordon, Mike; Creamer, Beverly; Harada, Wayne. "The Legacy: A Voice Of Hawai'i and Hawaiians". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Kamakawiwo, Israel (December 6, 2010). "Israel Kamakawiwo'ole: The Voice Of Hawaii". NPR. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Holub, Rona L. (2008). Kamakawiwo'ole, Israel Ka'ano'i (1959–1997), singer, musician, and activist for Hawaiian rights and sovereignty. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1803801. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Archived from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c Montagne, Renee (March 9, 2011). "Israel Kamakawiwo'ole: The Voice of Hawaii". NPR. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ "Article by Jay Hartwell of the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa". hawaii.edu. May 26, 1991. Archived from the original on August 21, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Ozzi, Dan (June 26, 2017). "20 Years Ago, Hawai'i Lost Its Greatest Musical Icon". Vice. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^

Guerin, Ada (June 6, 2006). "Chasing Rainbows". The Hollywood Reporter – International Edition. 394 (32). Los Angeles, CA, USA: Prometheus Global Media: M419. ISSN 0018-3660. Retrieved October 10, 2012. (subscription required)

Guerin, Ada (June 6, 2006). "Chasing Rainbows". The Hollywood Reporter – International Edition. 394 (32). Los Angeles, CA, USA: Prometheus Global Media: M419. ISSN 0018-3660. Retrieved October 10, 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ "Brudda Iz's Facing Future goes platinum, a first for Hawaii". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. October 6, 2005.

- ^ Kanai, Maria; Keany, Michael; Thompson, David (September 18, 2012). "The 25 Greatest Hawaii Albums of the New Century". Honolulu magazine. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Bolante, Ronna; Keany, Michael (June 1, 2004). "The 50 Greatest Hawai'i Albums of All Time". Honolulu magazine. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Carroll, Rick. Iz: Voice of the People. Honolulu, Hawai'i: Bess, 2006. Print.

- ^ Israel Kamakawiwo'ole. "Hawai'i '78." Facing Future. Mountain Apple Company, 1993. MP3.

- ^ "Hawaii State Motto Ua Mau Ke Ea O Ka Aina I Ka Pono The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness". Netstate.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ Tranquada, Jim (2012). The Ukulele: a History. University of Hawaii Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8248-3544-6.

- ^ Adamski, Mary (July 10, 1997). "Isles bid aloha, not goodbye, to 'Brudda Iz'". Starbulletin.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Rick (2006). Iz: Voice of the People. Bess Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-57306-257-2.

- ^ a b c Kekoa Enomoto, Catherine; Kakesako, Gregg K. (June 26, 1997). "'IZ' Will Always Be". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Adamski, Mary (July 10, 1997). "Isles Bid Aloha, not Goodbye, to 'Brudda Iz'". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ "OFFICIAL Somewhere over the Rainbow – Israel "IZ" Kamakawiwo'ole". Mountain Apple Company Inc. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "OFFICIAL – Somewhere Over the Rainbow 2011 – Israel "IZ" Kamakawiwo'ole". Mountain Apple Company Inc. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "Sculpture's Debut Honors 'Braddah IZ'". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. September 21, 2003. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Starauflauf Bei der Echo-Verleihung in Berlin" [Star-Studded Echo Awards Ceremony in Berlin]. Badische Zeitung (in German). March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "5 questions with Disney/Pixar's 'LAVA' director James Ford Murphy". KHON2. November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Israel Kamakawiwoʻole's 61st Birthday". Google.com. May 20, 2020. Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ "IMAX: Hubble 3D – Toronto Screen Shots". March 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Grant, Kim; Bendure, Glenda; Clark, Michael; Friary, Ned; Gorry, Conner; Yamamoto, Luci (2005). Lonely Planet Hawaii (7th ed.). Lonely Planet Publications. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-74059-871-2.

- ^ Burgos, Annalisa (January 7, 2023). "Hawaii music industry mourns death of award-winning engineer Milan Bertosa". Hawaii News Now. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Week Ending Oct. 2, 2011. Songs: Gone But Not Forgotten

- ^ Trust, Gary (October 21, 2014). "Ask Billboard: The Weird Connections Between Mary Lambert & Madonna". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "World Digital Song Sales". Billboard. August 27, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ Artist Chart History – Israel Kamakawiwo'ole, Billboard

- ^ Heller, Andreas (June 2011). "Herr der Goldtruhen" [Lord of the Chests of Gold]. Folio. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Lynx – Getting Dressed Commercial Song Israel Kamakawiwo'ole – Somewhere Over the Rainbow". YouTube. November 24, 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ "Musik-Jahrescharts: 'Sanfter Riese' und der Graf setzen sich durch – media control" [Music charts of the year: 'Gentle giant' and der Graf]. media-control.de (in German). January 6, 2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Israel Kamakawiwo'ole; 'Over the Rainbow')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- ^ "oe3.ORF.at / woche 42/2010". Charts.orf.at (in German). October 25, 2010. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ "Somewhere Over the Rainbow' by Israel Kamakawiwoʻole Reaches 1 Billion YouTube Views". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ "Bruddah Iz songs to be added to Library of Congress National Recording Registry". KHON. April 2021. Archived from the original on March 15, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Sources

- Carroll, Rick (2006). IZ: Voice of the people. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Bess Press. ISBN 978-1-57306-257-2. OCLC 71325451.

- Kois, Dan (2010). Facing Future. 33⅓. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826429056. OCLC 676695887.

External links

[edit]- 1959 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American singers

- American Christians

- American male songwriters

- Burials at sea

- Christians from Hawaii

- Converts to Christianity

- Deaths from respiratory failure

- Ukulele players from Hawaii

- Mountain Apple Company artists

- Musicians from Honolulu

- Na Hoku Hanohano Award winners

- Native Hawaiian musicians

- Native Hawaiian nationalists

- Respiratory disease deaths in Hawaii

- Singers from Hawaii

- Songwriters from Hawaii

- 20th-century American songwriters