Kabwe 1

14°27′36″S 28°25′34″E / 14.460°S 28.426°E

Replica (Museum Mauer, Germany) | |

| Common name | Kabwe 1 |

|---|---|

| Species | Homo heidelbergensis (Homo rhodesiensis) |

| Age | 324-274 ka |

| Date discovered | 1921 |

| Discovered by | Tom Zwiglaar |

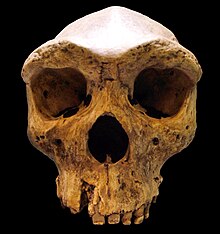

Kabwe 1, also known as Broken Hill Man or Rhodesian Man, is a nearly complete archaic human skull discovered in 1921 at the Kabwe mine, Zambia (at the time, Broken Hill mine, Northern Rhodesia). It dates to around 300,000 years ago, possibly contemporaneous with modern humans and Homo naledi. It was the first archaic human fossil discovered in Africa. Kabwe 1 was found near an exceptionally well-preserved tibia and femoral fragment, and potentially other bones whose provenance is uncertain. The fossils were sent to the British Museum, where English palaeontologist Sir Arthur Smith Woodward described them as a new species: Homo rhodesiensis. Kabwe 1 is now often classified as H. heidelbergensis. Zambia is negotiating with the UK for repatriation of the fossil.

Kabwe 1 is characterised by a massive brow ridge (supraorbital torus), low and long forehead, a prominence at the back of the skull, thickened bone, and a proportionally narrow lower face. The tibia may have belonged to someone about 179–184 cm (5 ft 10 in – 6 ft 0 in) and 63–81 kg (139–179 lb) in life, one of the biggest size estimations of an archaic human. Kabwe 1 presents severe tooth decay, possibly caused by overloading of the teeth, age, and lead poisoning, which may have become septic and ultimately lead to its death.

Kabwe 1 is associated with Middle Stone Age tools made of quartz, possibly the Lupemban culture. Kabwe 1 may have inhabited a cavern and butchered mainly large hoofed mammals. The Kabwe site probably featured miombo woodlands and dambos, like in recent times.

Research history

[edit]Discovery

[edit]

In 1902, engineer T. D. Davey discovered a major lead-zinc deposit in Northern Rhodesia[a] and named it Broken Hill, possibly in reference to the Australian lead-zinc Broken Hill ore deposit. He claimed the six kopjes (hills) in the area, and mining commenced in 1904 under the authority of the Broken Hill Mining Company. In 1906, when mining reached full-scale production, excavators dug into what is now known as the "Bone Cavern" in No. 1 Kopje, yielding animals bones and stone tools.[2] On June 17, 1921,[3] Swiss miner Tom Zwiglaar discovered a human skull at the back of the cavern when his "black boy" struck it with a pickaxe.[4] Miners mistook a mineralised calcitic deposit as mummified skin.[5] More fossils were reported the next year,[6] and Czech-American anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička discovered more in 1925.[7]

Like other fossils discovered at the site, the managing director of the company — Ross Macartney — sent the human remains to the British Museum.[8] In 1921, English palaeontologist Sir Arthur Smith Woodward made a short preliminary report, and the skeleton was described by English osteologist William Plane Pycraft in 1928.[9]

This was the first archaic human ever discovered in Africa, and at this point in time, many scientists had not expected to find such a specimen in this part of the world. The discovery elicited much scientific attention.[3]

Provenance

[edit]

Before mining operations, No. 1 Kopje was 50–60 ft (15–18 m) high with a depression in the middle. The Bone Cavern was at ground level, and the water table about 30 ft (9.1 m) below. When it was open, the cavern may have been 120–150 ft (37–46 m) east to west. The cavern may have been inhabited intermittently by humans and hyenas.[10] The skull was found in a mass of lead. The first account of the skull's discovery was published in 1921 by the Assistant Electrometallurgist W. E. Harris, who erroneously reported it came from a depth beneath the water table. This error was corrected by a site map earlier published in The Illustrated London News.[6]

At first, all human remains were reported to have been found together. In 1928, British palaeontologist Francis Arthur Bather suggested that the entire skeleton had actually been found, but most of it was destroyed before its significance was understood.[6] In 1929, Kenyan fossil hunter Louis Leakey interviewed miners working at the time, and concluded that the skull was found in isolation, and workers subsequently searched the dumps for more fossils; because only lead-mining was happening at Broken Hill at the time, the other fossils must have originated from younger zinc deposits higher up. Therefore, it was possible the skull and the other fossils belonged to two different species.[11] Similarly, when Hrdlička investigated the matter in 1930, Zwiglaar told him he found a human leg bone about 3 ft (91 cm) from the skull, but no other human remains.[12]

To test the provenance of the fossils, in 1947 the UK Government Chemist J. A. C. McClelland spectrographically measured the fossils' levels of lead, zinc, and vanadium. He found that the skull was instead the only fossil that contained more zinc than lead, and similarly there is an unpublished record in the archives of the British Museum which reported that the skull was originally encrusted in hemimorphite (a zinc silicate). The skull may have occupied a zinc pocket within a lead carbonate mass. Because all other fossils have high amounts of lead, all the fossils probably did originate from the older lead deposits.[6] Still, it is unclear if the unprovenanced fossils can be associated with the same species represented by Kabwe 1.[13]

The provenanced fossil specimens are:[14]

- E.686 (the skull)

- E.691 (left tibia)

- E.M.793 (femoral shaft)

The other unprovenanced fossils are:[14]

- E.897 (skull fragment)

- E.687 (right maxilla)

- E.898 (distal right humerus)

- E.719 (right hip bone)

- E.720 (right hip bone)

- E.688 (sacrum)

- E.907 (proximal right femur)

- E.689 (proximal left femur)

- E.6891 (distal left femur)

- E.690 (left femoral diaphysis)

Hrdlička described the unprovenanced fossils as anatomically the same as modern humans. He was hesitant to assign them to the same species as Kabwe 1.[15] In 1986, British physical anthropologist Chris Stringer noted at least one archaic feature on E.719, indicating that at least some of the unprovenanced fossils may represent an archaic human.[14]

Age

[edit]

Because of the uncertain provenance and the destruction of the site due to mining activity, determining a precise age for the Kabwe fossils has been problematic.[5] They at first were assumed to date to the Late Pleistocene because they were found with animals still alive today, and were associated with early Middle Stone Age tools. In 1973, American palaeontologist Richard Klein redated the Middle Stone Age (and therefore the Kabwe material) to the late Middle Pleistocene.[b] Biostratigraphic studies in the early 2000s drew comparisons with Olduvai Gorge and Elandsfontein, and similarly suggested a Middle Pleistocene age — maybe 500,000 years old. Kabwe 1 is also anatomically comparable to other African fossils better constrained to the early to mid Middle Pleistocene.[13]

Using electron spin resonance dating (ESR) of dentin adhering to tooth enamel fragments, and laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry of the inner and outer surfaces of a fragment of the base of the occipital bone of Kabwe 1, a 2020 study calculated an age of 298,000 ± 34,000 years for the former, and 301,000 ± 37,000 years for the latter method. They offered a best estimate of 299,000 ± 25,000 years (the weighted mean). Congruently, using uranium–thorium dating and ESR dating of the sediment scraped off the skull in 1921, they calculated an upper age limit of 322,000 years. The interval opens the possibility that Kabwe 1 was a contemporary of the Moroccan Jebel Irhoud, the oldest identified modern human fossil, and the South African Homo naledi.[5]

Classification

[edit]

When first detailing the Kabwe fossils in 1921, Woodward compared the skull to those assigned to Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), namely La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1. He noted that while the face is similar (though "more simian in appearance"), the braincase aligns somewhat more closely with modern humans (H. sapiens), so he decided to name a new species: H. rhodesiensis. Woodward said this might revitalise the hypothesis that human evolution went through a Neanderthal phase, with H. rhodesiensis being the step after Neanderthal.[8] In other polycentric models, Kabwe 1 was believed to be the direct ancestor of modern South African bushmen, or "Australo-Melanesians" as a descendant of the Indonesian Solo Man.[17][18] H. rhodesiensis was the third fossil member of the genus Homo, after H. heidelbergensis (Mauer 1) named in 1907.[6]

In his 1928 description of the fossil material, Pycraft believed that the skull was more closely allied with chimpanzees and gorillas than Neanderthals, and the hip joint only permitted an apelike gait. He recommended placing the Kabwe fossils into a new genus as "Cyphanthropus[c] rhodesiensis".[19][20] Pycraft's description, comparisons, and inferences were criticised by British writer Frederick Gymer Parsons, who rejected "Cyphanthropus" later that year.[20]

...the whole description is so loaded with rarely used technical terms and turgid sentences about unessential things, that it would be difficult for an ordinary anthropologist to grasp...All this no doubt would have been pointed out and put right had Mr. Pycraft been granted the help of a colleague trained in human anatomy...

— Frederick Gymer Parsons, 1928[20]

By the mid-20th century, human taxonomy was in turmoil, with several species and genera described on the basis of a single specimen. In 1950, German-American evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, surveying a "bewildering diversity of names", subsumed human fossils into three species of Homo: "H. transvaalensis" (the australopithecines), H. erectus, and H. sapiens, as had been broadly recommended by various priors. Mayr defined these species as a sequential lineage, with each species evolving into the next (chronospecies). For Kabwe, he recommended subspecific distinction at most as H. sapiens rhodesiensis.[21] Though Mayr's recommendations became popular, this left H. erectus and H. sapiens poorly defined.[22]

Kabwe 1 was widely classified under the umbrella of "archaic H. sapiens" (or H. sapiens sensu lato), a population which would eventually lead to anatomically modern H. sapiens (sensu stricto).[23] In 1974, British physical anthropologist Chris Stringer recommended reviving H. heidelbergensis defined by namely Kabwe 1, the Greek Petralona 1, the Ethiopian Bodo cranium, and the French Arago 21[d] ( a "Euro-African hypodigm"). Though this became a popular designation, in 2000, American anthropologists Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks argued that H. heidelbergensis should be reserved for only the direct ancestors of Neanderthals. They recommended reviving H. rhodesiensis to house African Middle Pleistocene fossils they believed were directly ancestral to modern humans.[16][22] As the age of human fossils became better resolved, it was discovered that modern humans existed at the same time as Kabwe 1 and other divergent specimens.[5] H. rhodesiensis is now usually considered to be a junior synonym of H. heidelbergensis.[25]

A 2021 phylogeny of some Middle Pleistocene fossils using tip dating:[26]

Description

[edit]

Skull

[edit]The Kabwe 1 skull measures 20.6 cm × 14.6 cm (8.1 in × 5.7 in) at maximum length x breadth.[27] It is exceptionally well preserved,[28] but part of the cranial vault and base are missing on the right side. The frontal bone (forehead) is long and low, the brow ridge (supraorbital torus) is tall and massive, and there is a big prominence at the back of the skull. The parietal bones are flat unlike H. erectus, the temporal lines are distinct especially towards the front, and the temporal fossa is small. There is moderate postorbital constriction. The frontal lobes extend only into the farthest back margins of the orbits (eye sockets).[23] The skull is notably thicker than modern human skulls and many other Middle Pleistocene fossils, but comparable to Petralona 1 and H. ergaster (African H. erectus).[28]

The orbits are square shaped and far apart. The bottom margins of the orbits slope down and out ("aviator glasses"). The piriform aperture (nose hole) and lower face are proportionally small, though in absolute size quite large. The cheekbones are relatively weak. The teeth are worn down and preserve little anatomical landmarks. The second and third molars are about the same size, and the third molar smaller.[23] Like many other specimens classified as H. heidelbergensis, the frontal and paranasal sinuses are extensive,[28] which may be a response to how well the thick supraorbital torus distributes biting strain across the skull, leading to bone resorption in low-strain regions.[29]

The brain volume was about 1,280 cc (78 cu in). The frontal lobes are asymmetrical, with the right projecting slightly farther forward and down, which is normally seen in right-handed people. The brain was long and low, unlike that of Neanderthals or modern humans, but still diverging from H. erectus.[28]

Postcranium

[edit]Among the postcranial (aside from the skull) material discovered in Kabwe, only the long tibia and possibly a femoral shaft are known to be directly associated with the skull. The tibia is one of the best preserved human tibiae predating the Late Pleistocene. The femoral material by and large agree with modern rather than archaic human anatomy, though are somewhat larger and thicker. The Kabwe tibial plateau (where the femur rests) is similarly large, like other Middle Pleistocene humans, indicating higher baseline body mass loads on the legs than modern humans. The Kabwe tibia may have belonged to someone who was about 179–184 cm (5 ft 10 in – 6 ft 0 in) and 63–81 kg (139–179 lb), the higher size estimates assuming a stocky build. This is one of the tallest height estimates of an archaic human.[13]

Compared to Bodo and Neanderthals, the Kabwe humerus has a narrower olecranon fossa (where the humerus connects with the ulna) and thicker adjacent pillars, better aligning with H. ergaster and most modern humans.[30]

The hip bone and socket generally align with what can be seen in modern humans, if somewhat more robust. In E.719, the cortical bone (hard outer layer of bone) is thicker and the ilium flares out laterally (towards the sides), causing a triangular prominence near the hip socket (acetabulocristal buttress) much like the older Olduvai Hominin 28 (either H. habilis or H. ergaster) and Arago 44. E.720 does not preserve this archaic feature.[14]

Pathology

[edit]Out of the 15 preserved teeth in Kabwe 1, 10 of them have cavities, 4 of which so severe that the tooth crown is destroyed (right and left 2nd premolar P4, right third molar M3, and left first molar M1). There is moderate-to-advanced gum disease. The surviving crowns are extremely worn, causing periapical periodontitis, alveolar bone destruction, hypercementosis, and cavities between the teeth. The front teeth are more heavily worn than the back, probably caused by an overbite. No other Pleistocene human fossil exhibits such severe tooth decay. The pathology may have resulted from regular overloading of the teeth, as well as xerostomia (dry mouth) due to possibly age and lead poisoning.[31]

These oral wounds seem to have become septic, causing septic arthritis of the tibia, mastoiditis (a middle ear infection), and abscess formation on the mastoid part of the temporal bone. The mastoid abscess may have progressed down the neck and into the chest, leading to death.[32]

Culture

[edit]

The Kabwe site yielded white quartz pieces that have chipped, cut, or scraped edges, which suggests that they were used as stone tools.[33] Hrdlička postulated that some of the animal bones, horns, and ivory were used as digging implements; and large quartzite pebbles (probably brought to the site from a far away source) were used to smash open bones to access the bone marrow.[33] Some perforated pieces of animal bone were also suggested to represent bone tools, but could also be explained by natural processes. In 1959, surveying what survived of the collection at that time (which are now lost), British archaeologist John Desmond Clark suggested the technology falls in the Middle Stone Age, possibly the Lupemban culture. This is because some of the tools are somewhat leaf-shaped (blades) — which may indicate the usage of the Levallois technique — and some may have been retouched to make one end blunt (backed tools) — characteristic of the culture.[34]

In 1907, in the first description of fossil material from Kabwe, Frederic Philip Mennell and E. C. Chubb (who were working for the Bulawayo Museum) concluded that fossils were accumulated by carnivore and human activity.[35] Hrdlička noted that every large animal fossil from Kabwe — including of carnivores and larger birds — had been broken into pieces, which he believed was done by the cavern inhabitants to access the bone marrow.[36] The large mammal fauna of Kabwe is mostly represented by hoofed animals. It includes: the lion, brown hyena, serval, leopard, slender mongoose, Machairodus, warthog, African elephant, African wild ass, Burchell's zebra, black rhinoceros, Sivatherium, kudu, common eland, cape buffalo, damalisk, wildebeest, and gerenuk. Clark noted in 1959 that other African Middle Pleistocene sites commonly feature similar herbivores with evidence of butchery.[37]

The small mammal fauna, probably accumulated by barn owls, indicate a similar biome to today, with all 24 rodent species except one (the lesser dwarf shrew) still found in the area today. Before mining operations degraded the area, Kabwe featured dambos (shallow wetlands) and miombo woodlands. The area can have dry seasons lasting up to 7 months.[38]

In 1947, Clark reported a non-naturally occurring, 60 mm (2.4 in), red-stained, spheroid piece of hematite (an iron oxide), which he believed was purposefully processed by the inhabitants. The occurrence of red hematite is relatively common in the Middle Stone Age, and may indicate symbolic thinking using red pigments, though this is unverifiable.[39]

Repatriation

[edit]When Zambia became independent in 1964, the name of the mine and nearby mining town changed from Broken Hill to Kabwe, meaning "place of smelting", in reference to pre-colonial iron metallurgy in the area.[2] Following the United Nation's 1973 resolution "Restitution of works of art to countries victims of expropriation", on April 30, 1974, the Zambian National Monuments Commission (NMC) formally requested the British Museum provide information on how Kabwe 1 was acquired, stored, and anything pertinent to a discussion on its return to Zambia. The British Museum responded on June 6 that it was donated by the Rhodesia Broken Hill Development Company, "who had been in the habit of presenting to the Museum with interesting paleontological specimens for a number of years." The NMC replied with a formal request of the return of Kabwe 1 because its removal without a permit violated the Bushman-Relics Protection Act, 1911. After the British Museum denied the request, Zambia attempted to petition the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee on the basis of the UNESCO 1970 Convention, which failed as the UK was not part of UNESCO at the time. The UK denied subsequent requests on the grounds that Kabwe 1 is more secure in the museum's collection, and better accessible to the world in London than Zambia, as an artefact of world heritage. In 2002, the Bizot group (a meeting of the world's largest museums) made a similar opinion on the repatriation of artefacts acquired during colonial times.[40]

In May 2018, at a meeting of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, British delegates agreed to negotiations with Zambia regarding eventual repatriation of Kabwe 1, accompanied by agreements regarding access to the skull and associated scans and digital data by researchers.[1]

See also

[edit]- Blombos Cave

- Florisbad Skull

- List of caves in South Africa

- Recent African origin of modern humans

- Skhul and Qafzeh hominins

Notes

[edit]- ^ Northern Rhodesia was named after British mining magnate Cecil Rhodes.[1]

- ^ At first, the African Middle Stone Age was thought to be "cultural backwater" as a contemporary of the European Upper Palaeolithic, but archaeologists in the 1970s discovered it was actually contemporary with the European Middle Palaeolithic.[16]

- ^ Meaning "stooping man", from Ancient Greek κυφός + ἄνθρωπος[13]

- ^ In 2015, French palaeoanthropologist Marie-Antoinette de Lumley recommended classifying the Arago material as H. erectus tautavelensis, resurrecting the taxon she and her husband Henry erected in 1979[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Balter, Michael (2019-02-18). "Zambia's Most Famous Skulls Might Finally Be Headed Home". www.theatlantic.com. The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ a b Southwood, M.; Cairncross, B.; Rumsey, M. S. (2019). "Minerals of the Kabwe ("Broken Hill") Mine, Central Province, Zambia". Rocks & Minerals. 94 (2): 115–118. doi:10.1080/00357529.2019.1530038.

- ^ a b Hrdlička 1930, p. 98.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e Grün, R.; Pike, A.; McDermott, F.; Eggins, S.; Mortimer, G.; Aubert, M.; Kinsley, L.; Joannes-Boyau, R.; Rumsey, M.; Denys, D.; Brink, J.; Clark, T.; Stringer, C. (2020). "Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution". Nature. 580: 372–375. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2165-4.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, J. D.; Oakley, K. P.; Wells, L. H.; McClelland, J. A. C. (1947). "New Studies on Rhodesian Man". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 77 (1): 7–10. doi:10.2307/2844533. JSTOR 2844533.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 113.

- ^ a b Woodward, A. S. (1921). "A New Cave Man from Rhodesia, South Africa". Nature. 108: 371–372. doi:10.1038/108371a0.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 116.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Leakey, L. S. B. (1935). "The Findings of the Broken Hill Skull". The Stone Age Races of Kenya. Oxford University Press. pp. 680–681.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, pp. 105.

- ^ a b c d Trinkaus, E. (2009). "The Human Tibia from Broken Hill, Kabwe, Zambia". PaleoAnthropology: 145–165. ISSN 1545-0031.

- ^ a b c d Stringer, C. B. (1986). "An archaic character in the Broken Hill innominate E. 719". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 71 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330710114.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b McBrearty, S.; Brooks, A. S. (2000). "The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior". Journal of Human Evolution. 39: 480–481. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435.

- ^ Keith, A. (1944). "Evolution of Modern Man (Homo sapiens)". Nature. 153: 742. doi:10.1038/153742a0.

- ^ Curnoe, D. (2011). "A 150-Year Conundrum: Cranial Robusticity and Its Bearing on the Origin of Aboriginal Australians". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011: 2–3. doi:10.4061/2011/632484. PMC 3039414. PMID 21350636.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c Parsons, F. G. (1928). "British Museum (Natural History) Rhodesian Man and Associated Remain". Nature. 122 (3082): 798–800. doi:10.1038/122798a0.

- ^ Mayr, E. (1950). "Taxonomic categories in fossil hominids". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 15 (0): 109–118. doi:10.1101/SQB.1950.015.01.013.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, J. H.; Tattersall, I. (2010). "Fossil evidence for the origin of Homo sapiens". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 143 (S51): 99–103. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21443. PMID 21086529.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, J. H.; Tattersall, I. (2003). The Human Fossil Record. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 108–111. doi:10.1002/0471722715.ch2. ISBN 978-0-471-31928-3.

- ^ de Lumley, M.-A. (2015). "L'homme de Tautavel. Un Homo erectus européen évolué. Homo erectus tautavelensis" [Tautavel Man. An evolved European Homo erectus. Homo erectus tautavelensis]. L'Anthropologie (in French). 119 (3): 342–344. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2015.06.001.

- ^ Sarmiento, E.; Pickford, M. (2022). "Muddying the muddle in the middle even more". Evolutionary Anthropology. 31 (5): 237–239. doi:10.1002/evan.21952. PMID 35758530. S2CID 250071605.

- ^ Ni, Xijun; Ji, Qiang; Wu, Wensheng; Shao, Qingfeng; Ji, Yannan; Zhang, Chi; Liang, Lei; Ge, Junyi; Guo, Zhen; Li, Jinhua; Li, Qiang; Grün, Rainer; Stringer, Chris (2021). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. ISSN 2666-6758. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Balzeau, A.; Buck, L. T.; Albessard, L.; Becam, G.; Grimaud-Hervé, D.; Rae, T. C.; Stringer, C. B. (2017). "The Internal Cranial Anatomy of the Middle Pleistocene Broken Hill 1 Cranium". PaleoAnthropology: 130–133. doi:10.4207/PA.2017.ART107. ISSN 1545-0031.

- ^ Godinho, R. M.; O'Higgins, P. (2018). "The biomechanical significance of the frontal sinus in Kabwe 1 (Homo heidelbergensis)". Journal of Human Evolution. 114: 141–153. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.10.007.

- ^ Carretero, J. M.; Haile-Selassie, Y.; Rodriguez, L.; Arsuaga, J. L. (2009). "A partial distal humerus from the Middle Pleistocene deposits at Bodo, Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Anthropological Science (117): 24. doi:10.1537/ase.070413.

- ^ Lucy, S. A. (2014). "The oral pathological conditions of the Broken Hill (Kabwe) 1 cranium". International Journal of Paleopathology. 7. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2014.06.005.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 121.

- ^ a b Hrdlička 1930, p. 140.

- ^ Barham, L.; Llona, A.; Stringer, C. (2002). "Bone tools from Broken Hill (Kabwe) cave, Zambia, and their evolutionary significance". Before Farming. 2002 (2): 1–16. doi:10.3828/bfarm.2002.2.3.

- ^ Mennell, F. P.; Chubb, E. C. (1907). "On an African Occurrence of Fossil Mammalia Associated with stone Implements". Geological Magazine. 4 (10): 443–448. doi:10.1017/S0016756800133849.

- ^ Hrdlička 1930, p. 112.

- ^ Clark, J. D. (1959). "Further Excavations at Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 89 (2): 225–230. doi:10.2307/2844270.

- ^ a b Avery, D. M. (2016). "Micromammals from the type site of Broken Hill Man (Homo rhodesiensis) near Kabwe, Zambia: a historical note". Historical Biology. 30 (1–2): 276–283. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1297434.

- ^ Barham, L. S. (2002). "Systematic Pigment Use in the Middle Pleistocene of South‐Central Africa". Current Anthropology. 43 (1): 181–190. doi:10.1086/338292.

- ^ Lusonda, F. B. (2013). "Decolonising the Broken Hill Skull: Cultural Loss and a Pathway to Zambian Archaeological Sovereignty". African Archaeological Review. 30 (2): 208–216. doi:10.1007/s10437-013-9134-3.

Sources

[edit]- Hrdlička, A. (1930). "The skeletal remains of early man". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 83 (1): 98–144.