Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

| Cube of Zoroaster | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Former names | Bon-Khanak (Sassanian era) |

| Alternative names | Kornaykhaneh Naggarekhaneh |

| General information | |

| Type | Tower, stone chamber |

| Location | Marvdasht, Iran |

| Construction started | First half of sixth century B.C., Achaemenid era |

| Owner | Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Iran |

| Website | |

| http://www.persepolis.ir/ | |

Ka'ba-ye Zartosht (Persian: کعبه زرتشت), also called the Cube of Zoroaster, is a rectangular stepped stone structure in the Naqsh-e Rustam compound beside Zangiabad village in Marvdasht county in Fars, Iran. The Naqsh-e Rustam compound also incorporates memorials of the Elamites, the Achaemenids and the Sasanians.

The Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is 46 metres (151 ft) from the mountain, situated exactly opposite Darius II's mausoleum. It is rectangular and has only one entrance door. The material of the structure is white limestone. It is about 12 metres (39 ft) high, or 14.12 metres (46.3 ft) if including the triple stairs, and each side of its base is about 7.30 metres (24.0 ft) long. Its entrance door leads to the chamber inside via a thirty-stair stone stairway. The stone pieces are rectangular and are simply placed on top of each other, without the use of mortar; the sizes of the stones varies from 0.48 by 2.10 by 2.90 metres (1 ft 7 in by 6 ft 11 in by 9 ft 6 in) to 0.56 by 1.08 by 1.10 metres (1 ft 10 in by 3 ft 7 in by 3 ft 7 in), and they are connected to each other by dovetail joints.

Etymology

[edit]The structure was built in the Achaemenid era and there is no information of the name of the structure in that era. It was called Bon-Khanak in the Sassanian era; the local name of the structure was Naggarekhaneh (naggar "keep/hold" + -e "of" + khaneh "house"). The phrase Ka'ba-ye Zartosht has been used for the structure from the fourteenth century into the contemporary era.

Various views and interpretations have been proposed for the purpose of the chamber, but none of them can be accepted with certainty. Some consider the tower a fire temple and a fireplace, and believe that it was used for igniting and worshiping the holy fire. Another theory is that it is the mausoleum of one of the Achaemenid shahs or grandees, due to its similarity to the Tomb of Cyrus and some mausoleums of Lycia and Caria. Other Iranian scholars believe the stone chamber to be a structure for the safekeeping of royal documents and holy or religious books, but the chamber of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is too small for this purpose. Other less noticed theories, such as its being a temple for the goddess Anahita or a solar calendar, have also been mentioned.

In the Sassanian era, three inscriptions were written in the three languages Sassanian Middle Persian, Arsacid Middle Persian and Greek on the northern, southern and eastern walls of the tower.[1] One of them belongs to Shapur I the Sassanian, and another to the priest Kartir. According to Walter Henning, "These inscriptions are the most important historical documents from the Sassanian era."[2] The Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is a beautiful structure: its proportions, lines and external beauty are based on well-executed architectural principles.[3]

Currently, the structure is part of the Naqsh-e Rustam compound and owned by the Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Iran.

Name

[edit]

Alireza Shapur Shahbazi believes that the phrase Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is relatively new and inaccurate, originating around the fourteenth century.[citation needed] When the structure was discovered by the Europeans, its local name was Karnaykhaneh or Naggarekhaneh; the Europeans considered it a special site for worshiping fire, since the inside of the structure was blackened by smoke, and because they mistook the Zoroastrians for fire-worshipers, they attributed the place to them and named it the Zoroastrians' fire temple. As the shape of the structure was cuboid and the black stones that were placed on the white background of its walls resembled the Black Stone, the Muslims' Kaaba, it became famous as Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, the Kaaba of Zoroaster.[2]

The Encyclopedia Iranica explains about the name of the structure: "Ka'ba-ye Zartosht has probably acquired its name in the fourteenth century, the time that the ruined ancient sites in the whole Iran were attributed to characters in the Quran or Shahnameh. This does not mean that the place has been Zoroaster's mausoleum and there is also no report of the pilgrims' travels there for pilgrimage."[4]

Due to the discovery of Kartir's inscription on its walls, it is revealed that the name of the structure in the Sasanian era was Bon Khaanak, meaning the Cold Foundation, as the inscription reads:[5] "This Cold Foundation will belong to you. Act as the best way you see suitable that will delight our gods and purpose (implying Shapur I)." There is no knowledge of the name of the structure in any earlier periods.[2]

Ibn al-Balkhi has mentioned the name of the area of Naqsh-e Rustam and its mountain as Kuhnebesht, and has considered that the reason behind its naming was that the book Avesta was held there.[6] The word Dezhnebesht or Dezhkatibehs might have also been used for the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.[5]

Attributes

[edit]

Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is cuboid in shape, and has only one entrance door, which leads inside its chamber by means of a stone stairway. There are four blind windows on each of its sides.[7] The stone used is white marbly limestone, and there are dentate shelves of black stone on its walls. The limestone blocks were brought from Mount Sivand, where they were quarried in a place called Na'l Shekan ("horseshoe breaker"), to Naqsh-e Rustam to build the Ka'ba.[5] These blocks were chiselled into large, mostly rectangular pieces and are put in place atop each other without using mortar; in some places, such as the rooftop, the stones are connected to each other by dovetail joints.[8] The size of the stones varies from 2.90 by 2.10 by 0.48 metres (9 ft 6 in by 6 ft 11 in by 1 ft 7 in) to 1.10 by 1.08 by 0.56 metres (3 ft 7 in by 3 ft 7 in by 1 ft 10 in); however in the west wall, there is a flat stone that is 4.40 metres (14 ft 5 in) long.[2]

Four large rectangular pieces of stone form the ceiling/roof, placed along an east–west axis. Each of those stones are 7.30 metres (24.0 ft) long, connected to each other by dovetail joints, and the chipping method used to form them has given the roof the shape of a short pyramid. The anathyrosis style is used here in placing the stones atop each other, but no accurate order is retained in the 'ranking' of the stones. In some places, 20 rows, and in others 22 rows of stones are placed, and this continues to the ceiling. Wherever the original builders discovered any flaw in the main stone, the flawed area was removed and filled in with delicate joints, some of which still remain.[2]

To prevent the finished building from becoming too simple or monochrome, its creators added two architectural diversities: firstly, forming double-edged shelves from one or two flat plates of grey-black stone and placing them on the walls; secondly, carving small rectangular pits into the upper and middle sections of the outer walls that give a more delicate appearance to the tower's faces. The black stones were probably brought from Mount Mehr in Persepolis, and installed on the walls in three rows:[2]

- High on the walls just below the ceiling, a small rectangular shelf in the northern side, and two similar shelves on each of the other sides

- Three metres (9.8 ft) below the ceiling, two large square shelves on three sides and one small rectangular shelf on the northern side

- Six metres (20 ft) below the ceiling, two medium-sized rectangular shelves on three sides and one large rectangular on the northern side

Stairway

[edit]

A thirty-stair stairway (each stair is 2 to 2.12 metres (6 ft 7 in to 6 ft 11 in) long, 26 centimetres (10 in) wide and 26 centimetres (10 in) high) is placed in the middle of the northern wall, reaching the threshold of the entrance doorway. Thus, the intention was for the Ka'ba to look like a three-floor tower that has seven doors or hatches on each floor; but only one hatch has been made into a true door, while the others are left as holeless blind windows.[2]

The structure stands on a three-tiered platform. The first tier is 27 centimetres (11 in) above the ground, and the tower is 14.12 metres (46 ft 4 in) high including the triple tiers or stairs of its platform. The base is square-shaped, with each side approximately 7.30 metres (24.0 ft) long. The ceiling of the structure is smooth and flat on the inside, but its roof has a bilateral slope that begins from the line in the middle of the rooftop on the outside, creating the pyramid-like appearance previously mentioned. The doorway is 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) high and 87 centimetres (34 in) wide and at one point had a very heavy two-panel door which is now missing. There are carved-out notches for the upper and lower heels of each door panel in the stone frame which are visible to modern observers.[9] Some have assumed that the door would have been made of wood, but a stone door, very similar to the remains of the one found in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, exists in Solomon's Prison in Pasargadae, which indicates that both doors were made of stone.[10] The doorway leads to a single interior room. This space is quadrangular, has an area of 3.74 by 3.72 metres (12.3 by 12.2 ft), and is 5.5 metres (18 ft) high, with the thickness of its walls being between 1.54 and 1.62 metres (5 ft 1 in and 5 ft 4 in).[2]

History

[edit]

The Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is undoubtedly from the Achaemenid era. Much of the available evidence shows that it was built in the early Achaemenid era; the most important evidence for this dating is as follows:[2]

- Using black stone on a white background is one of the features of Pasargadian architecture.

- The dovetail joints are found mostly in the periods of Darius I and Xerxes I, and the way the stones are aligned is similar to the primary structures of Persepolis.

- The doorway and door of the structure is similar to those of the Achaemenid shahs' mausoleums, all of which have used the design of Darius I's mausoleum.

- The masonry, which lacks mortar or ordering, resembles the first parts of the platform of Persepolis that were constructed in Darius I's period. Especially, the inscription on the lower part of the southern wall of Persepolis is almost the same size as the stones forming the ceiling of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.

Carsten Niebuhr, who had visited the structure in 1765, writes: "Opposite the mountain that has the mausoleums and petroglyphs of Rostam's braveries, a small structure is built of white stone that is covered by only two pieces of large stones."[9] Jane Dieulafoy, who visited Iran in 1881, also reports in her travel journal: "...and then we saw a quadrilateral structure that was placed opposite the walls of the cliff. Each of its surfaces was like those of the ruined structure that we had seen in the Palvar desert..."[9]

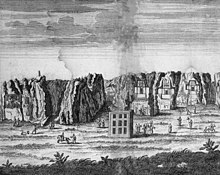

The first illustrations of the structure were made in the seventeenth century by European tourists like Jean Chardin, Engelbert Kaempfer and Cornelis de Bruijn in their travel books; but the first scientific description and excavation reports of the structure were done by Erich Friedrich Schmidt that had pictures and illustrated blueprints.[4][11]

The Naqsh-e Rustam compound was first investigated and probed along with the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht structure by Ernst Herzfeld in 1923.[11] Additionally, the compound was probed by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago under the leadership of Erich Schmidt in several seasons between 1936 and 1939, finding important works like the Middle Persian version of the Great Inscription of Shapur I, which was written on the wall of the structure.[11]

Purpose

[edit]

The purpose or usage of the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht structure has always been controversial between archaeologists and researchers and various views and interpretations have been stated about its application; but what makes its interpretation even more difficult, is the existence of a similar structure in Pasargadae, which makes one evaluate every probability with its circumstances too and consider a similar interpretation for both.[12] Some archaeologists have believed the structure to be a mausoleum;[4] and some others like Roman Ghirshman and Schmidt have said that Ka'ba-ye Zartosht was a fire temple in which the holy fire was placed and it was used during religious ceremonies.[13] Another group including Henry Rawlinson and Walter Henning believe that the structure was the treasury and the place for keeping religious documents and Avesta.[2][12] A small group believes the structure to be the temple of Anahita and believes that the goddess's statue was kept in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.[14][15] Heleen Sancisi Weerdenburg believes the building to be a structure constructed by Darius I for coronation;[4] and Shapur Shahbazi believes that Ka'ba-ye Zartosht was an Achaemenid mausoleum that was used as a site for the treasury of religious documents in the Sasanian era.[2]

Erich Friedrich Schmidt says about the importance of the structure:[2]

The outstanding effort that was necessary for creating this architectural masterpiece, was only used for building a single and dark chamber. Besides, the fact that they did or could close the only entrance door of a structure with a heavy and two-panel door, makes it clear that its content should be kept safe from robbery and pollution.

Fireplace

[edit]Engelbert Kaempfer first proposed the assumption of being a fire temple or fireplace; and following him, James Justinian Morier and Robert Ker Porter supported the view in the early nineteenth century. The southwestern corner of the chamber is blackened by smoke; and has caused the assumption that the holy fire was glowing in there.[2]

In the following years, Ferdinand Justi, Ghirshman, Schmidt and some others supported the hypothesis of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht being a fireplace. One of the reasons of this group is that Darius I says in the Behistun Inscription (First column, 63): "...I rebuilt the temples that Gaumata had destroyed. I returned the pastures, flocks, slaves and houses that Gaumata had taken to the people..."[17] Thus, there were some "temples" in the periods of Cyrus II and Cambyses II that Gaumata destroyed and Darius rebuilt them the same way; and since "Solomon's Prison" in Pasargadae is belonging to the first Achaemenid era and destroyed, and its exact copy was built in Naqsh-e Rustam in Darius's period, it should be concluded that those two structures are the mentioned temples in the Behistun Inscription; and since any temple in Persia during Darius's period could not be anything other than the holy fire, those were all fireplaces;[2] besides, Ka'ba-ye Zartosht has been conserved well even after the Achaemenid era and was not surrounded by soil and stones; and in the beginning of the Sasanian era, Shapur I composed the most important document of the Sasanian history on it and Kartir wrote a religious document on it. These show that the structure was religiously important. On the other hand, a structure is drawn on the coins of some Persian kings like those of Otophradates I that is a fireplace and the royal fire was kept above or inside it; and since the structure has a two-stair platform and its two doors are like Ka'ba-ye Zartosht and the center of the Persian kingdom was also in the city of Istakhr, it is the very Ka'ba-ye Zartosht that is drawn on their coins; and on the ceiling of this structure are put three fireboxes and the Persian king is standing in a praying posture in front of it.[2][18]

However, these reasons can not be true, for "Ayadana" only means "worshiping place" and a worshiping place is not necessarily a temple; and on the other hand, if you want to say that the people worshiped in this place, it is not true, for the Ka'ba is so small that the compound within can not fit more than two persons.[13] Furthermore, according to Herodotus (section "On the Customs of the Persians"), the Persians, even in his time, had no temples or statues of gods. Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin in Iranica identifies the ayadana as podiums.[19]

Additionally, in Achaemenid seals and on their mausoleums, it is seen that the fireboxes containing the royal fire were placed in the free space; and the royal fire was taken before the king in a portable firebox. A remarkable point that Herzfeld, Sami and Mary Boyce have made is that it seems improbable to have spent all that price and effort to keep the fire in a dark and holeless room that needed the door open for the fire to ignite.[2] Because fire requires oxygen and the inside of the Ka'ba is built in a way that even an oil lamp can not glow more than a few hours when the door and the large stone entrance are sealed.[13] The chamber does not have an exit way for smoke while its entrance door has always been sealed.[4][12]

The structure on the coins of Persian kings can not be Ka'ba-ye Zartosht; for the mentioned picture on the coins was not higher than 2 metres (6 ft 7 in), had a two-stair platform and no stairway is seen below its doorway; its entrance door is much larger relative to the structure than that of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht; its ceiling has no steepness, enough to be put three fireboxes on; there is no distance between its doorway and the ceiling; it has no crowns or portals; and the dents showing the heads of its arrows are not more than six. These features generally contradict with those of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.[2]

Mausoleum

[edit]

Most of the researchers assume the tower as the mausoleum of one of the Achaemenid shahs. Since it is very similar to the Tomb of Cyrus and some of the mausoleums of Lycia and Caria in shape, solidness of architecture and having a small room with a very heavy door, it is considered a mausoleum. Welfram Klyse and David Stronach believe that the Achaemenid structures in Pasargadae and Naqsh-e Rustam might have been influenced by Urartian art in the tower-like temples of Urartu.[20] Aristobulus, one of the retainers of Alexander III of Macedon, mentions the structure known as "Solomon's Prison" as "the tower-like mausoleum" while describing Pasargadae;[21] and if the mentioned structure is presumed the mausoleum of one of the Achaemenid shahs, due to its similarity to the structure Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, and as Franz Heinrich Weißbach and Alexander Demandt have explained, the structure should inevitably be considered belonging to another one of the Achaemenid shahs. Besides that, Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is a near to the mausoleums that were built at the same time; and all of them were later separated from the other parts of Naqsh-e Rustam by a chain of fortifications, indicating that they were all originally the same type and had similar applications. In other words, all of them, including they very Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, were mausoleums of Achaemenid grandees.[2][4]

Some other reasons can be stated for Ka'ba-ye Zartosht being a mausoleum; one is the triad and heptad units that are seen in the Achaemenid mausoleums. For example, the three-tomb chambers of the mausoleums connect them to making Ka'ba-ye Zartosht three-floor and its platform having three stairs;[4] and the seven hatches of each floor of the structure remarks the Seven Persian Noblemen on the mausoleums and the Tomb of Cyrus having seven floors.[2]

However the probations done do not confirm the idea and the writings carved on the walls of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht have no indication to the existence of a mausoleum or tomb either.[4]

Treasury

[edit]The idea of the structure being a treasury was first stated by Rawlinson in 1871. Rawlinson's reasons were the accurate architecture and the proper size of the chamber, its sole door being heavy and solid and that it was difficult to reach inside the structure. Walter Henning presented the theory with newer reasons. One of his reasons is about the inscriptions carved on the rim of the chamber; there is a large inscription by Shapur I on the walls of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht; and below that inscription, there is a writing by Kartir[22] that states in its second line: "This "bon khanak" will be yours; do with it as you believe is better for the gods and us."[23] Some historians conclude that it means the place was used for keeping religious bills, flags and documents.[13] While describing landmarks in Istakhr, Ibn-al Balkhi mentioned the site with the title "Kuh-Nefesht" or "Kuh-Nebesht" and said that the Avesta was kept there.[24] Henning believed that Ibn-al Balkhi meant the very Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.[25] However, there is to date no scholarly consensus. Some argue that the chamber of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht is too small to keep the Avesta and other religious books and royal flags; a wider and larger site was necessary for such an intention. In addition, some point out the relatively remote location of the structure suggests another use, as the various palaces of the Achaemenid shahanshahs as well as other official and governmental buildings would be better suited for keeping the Avesta and royal flags.

Side view

[edit]In the recent years, Reza Moradi Ghiasabadi has presented a new interpretation of the structure by doing field research and considers it an observatory and a solar calendar and believes that the blind windows, the stairs opposite the entrance door and the construct have been a timer or a solar index for measuring the rotation of the sun and subsequently keeping the record of the year and counting the years and extracting calendars and detecting the first days of each solar month and summer and winter solstices and spring and fall equinoxes. He concludes that the beginning of each solar month could be detected by observing the shadows formed on the blind windows.[26]

However, this theory can not be completely true; and one of the reasons that can be stated to refute the theory is that the direction of the geographic North of each region could be different from the direction of the magnetic North. The orbital inclination of the magnetic North from the geographic North is about 2.5 degrees in the Naqsh-e Rustam compound; and the magnetic orbital inclination of the structure is 18 degrees to the West relative to the magnetic North based on Schmidt's calculations. Therefore, the inclination of the structure relative to the geographic North will be about 15.5 degrees; meanwhile Ghiasabadi has considered the 18 degrees as the inclination of the structure from the geographic North.[27]

Inscriptions by Shapur I and Kartir

[edit]

On 1 June 1936, following the probations by the digging department of The University of Chicago Oriental Institute, some inscriptions were found on the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht structure that belonged to Shapur I and the priest Kartir;[14][28] Shapur's Inscription is written in the three languages Greek (70 lines), Arsacid Middle Persian (30 lines) and Sassanian Middle Persian (35 lines) on three sides of the structure; and Kartir's Inscription, which is in 19 lines in Sassanian Middle Persian language, is below Shapur's.[2]

In Shapur's Inscription, which should be considered the "Revolution Resolution" of the Sassanian dynasty,[29] he first introduces himself and mentions the regions he ruled and then describes the Persian-Roman Wars and indicates the defeat and death of Marcus Antonius Gordianus, after whom the Roman forces proclaimed Marcus Julius Philippus the emperor; and the latter paid Shapur a compensation equal to half a million gold dinars for reprieve and returned to his homeland. Following that, Shapur has described his battle with the Romans along with an elaborate list of the Roman states from which he had gathered the forces. The battle, which was for Armenia, was the largest defeat that the Sassanians inflicted upon the Romans.[30] Shapur then adds that "I apprehended Caesar Valerian myself, by my own hands." and mentions the names of the lands that he conquered in that battle. He then appreciates the power of God for giving him the power for victory and launches a lot of fire temples for his satisfaction to remark the names of the people who were involved in establishing the Sassanian government in front of the fire and finally advises the successors to strive for divine work and charity affairs.[2] The inscription is historically considered very interesting and one of first class proofs of the Sassanian era;[29] and one of the most important documents of the period for the limits and spans of the Sassanian Persian borders.[31] In addition, the inscription is the last time that the Greek alphabet and language is used in Persian inscriptions.[14]

Kartir's Inscription, which is situated below the Sassanian Middle Persian inscription of Shapur's, is written during Bahram II's reign and around 280 A.D.[2] He first introduces himself and then mentions his ranks and titles during the periods of the previous kings and says that he had the Herbad title during Shapur I's period and was appointed as "the grand master of all priests by Shahanshah Shapur I" and had the honor of receiving a hat and a belt by the shahanshah in Hormizd I's period and has achieved an increasing power and acquired the nickname "The Priest of Ahura Mazda, the god of gods".[9][31] Then, Kartir mentions his religious activities like fighting other religions such as Christianity, Manichaeism, Mandaeism, Judaism, Buddhism and Zoroastrian heresy and remarks founding fire temples and allocation of donations for them.[9] He also talks about correcting the priests that were, in his opinion, perverted and mentions the list of the states that were conquered by Persia during Shapur I's period and eventually the inscription ends with a prayer.[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Henning. The Middle Persian Inscriptions.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Shahbazi. The Illustrated Description of Naqsh-e Rustam.

- ^ Behnam. Naqsh-e Rustam and the Coronations of the Sassanian Kings.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gropp. "KAʿBA-YE ZARDOŠT". In Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ a b c Sami. The Most Important and Large Writing from the Sasanian Empire Era.

- ^ Ibn al-Balkhi. Fārs-Nāma.

- ^ Behnam. Naqsh-e Rustam in the Coronations of the Sasanian Kings.

- ^ ""The Ka'bah-i-Zardusht". University of Chicago Oriental Institute".

- ^ a b c d e Rajabi. Kartir and His Inscription in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.

- ^ Sami. The Sasanian Civilization.

- ^ a b c Schmidt. The treasury of Persepolis and other discoveries in the homeland of the Achaemenians.

- ^ a b c Lendering. Naqš-i Rustam.

- ^ a b c d Behnam. Naqsh-e Rustam and the Coronations of Sasanian Kings.

- ^ a b c "University of Chicago Oriental Institute". Archived from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ^ Farehvashi. Iranvij.

- ^ Sarfaraz and Avarzamani. Persian Coins: Since the Beginning until the Zand Era.

- ^ Sharpp. The Commands of the Achaemenid Shahanshahs.

- ^ Nafisi. The History of the Civilization of Sasanian Persia.

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ Fisher, W.B. The Cambridge History of Iran.

- ^ Arrian. The Anabasis of Alexander – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Tafazzoli. The History of Persian Literature Before Islam.

- ^ Yarshater. Kartir's Inscriptions.

- ^ Ibn-al Balkhi. Fars-Nameh.

- ^ Sami. The Most Important and Largest Writing from the Sassanian Empire Era.

- ^ Ghiasabadi. The Calendarial and Astronomic Structures.

- ^ Riazi. The Criticism of Moradi Ghiasabadi's Theory about the Astronomic Application of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht.

- ^ Nafisi. The History of the Sassanian Persian Civilization.

- ^ a b Bayani. The Parthian Dusk and the Sassanian Dawn.

- ^ Shahbazi. "SHAPUR I". In Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ a b Eshraghi. Introduction of Religion in the Sassanian Government.

- ^ Tafazzoli. The History of Persian Literature before Islam.

Bibliography

[edit]- Boyce, Mary (1975), "On the Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (3): 454–465, doi:10.2307/599356, JSTOR 599356

- Frye, Richard N. (1974), "Persepolis Again", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 33 (4): 383–386, doi:10.1086/372376, S2CID 222453940

- Gropp, Gerd (2004), "Ka'ba-ye Zardošt", Encyclopaedia Iranica, OT 7, New York: iranica.com

- Goldman, Bernard (1965), "Persian Fire Temples or Tombs?", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 24 (4): 305–308, doi:10.1086/371824, S2CID 162207461

- Herzfeld, Ernst (1935), Archaeological History of Iran, London: H. Milford/OUP

- "KARTIR KZ.; Royal inscription found on the Kabah of Zartusht. An account of how Zoroastrianism was propagated beyond Iranian territories during the Third Century, and other religions suppressed". avesta.org. AVESTA – Zoroastrian Archives. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1472425522.

External links

[edit]- A guided tour of Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, YouTube (1 min 34 sec).

- Buildings and structures completed in the 1st millennium BC

- Marvdasht complex

- Achaemenid architecture

- Naqsh-e Rustam

- Achaemenid Empire

- Buildings and structures in Fars province

- Sasanian inscriptions

- Middle Persian

- Parthian language

- Religion in the Sasanian Empire

- Cuboids

- Buildings and structures on the Iran National Heritage List