Kansas City Police Department

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

| Kansas City Police Department (Missouri) | |

|---|---|

Patch of the Kansas City Police Department | |

Flag of Kansas City, Missouri | |

| Common name | Kansas City Police Department |

| Abbreviation | KCPD |

| Motto | To Serve and Protect |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | April 15, 1874 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Employees | 2,020 (2021) |

| Annual budget | $249 million (2021)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Kansas City, Missouri, Missouri, US |

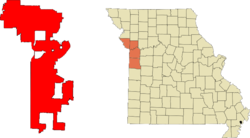

| |

| Map of Kansas City Police Department (Missouri)'s jurisdiction | |

| Legal jurisdiction | City of Kansas City, Missouri |

| Governing body | Governor of Missouri |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 1125 Locust Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106 |

| Police Officers | 1,098 (2023) |

| Corrections personnel and Civilian members | 500 Corrections (2023) |

| Police Commissioners responsible |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Stations | 6

|

| Facilities | |

| Detention Centers | 1 |

| Website | |

| Kansas City Police Department official website | |

The Kansas City Police Department (KCPD) is the principal law enforcement agency serving Kansas City, Missouri. Jackson County 16th Circuit Court Circuit Court Judge Jen Phillips swore in Stacey Graves as the 46th chief of police of the KCPD on December 15, 2022.[2] Graves, who served as head of the KCPD's Deputy Chief of the Patrol Bureau,[3] became the city's 46th police chief on December 15, 2022.[4]

History

[edit]The Kansas City Police Department was founded in 1874. George Caleb Bingham was the first president of the Board of Police Commissioners. The first Chief was Thomas M. Speers. From its inception the department was under the control of the Commissioners, appointed by the Missouri governor. In 1932 the police department came under local control for the first time during the Pendergast era. After significant corruption the Board was reinstated and around half of employees fired.[5][6] Following the St. Louis police return to home rule in 2013, Kansas City is the only major city in the country without local control of the police department.[7]

The Kansas City preventive patrol experiment was a landmark experiment carried out between 1972 and 1973 by the Kansas City Police Department. It was evaluated by the Police Foundation. It was designed to test the assumption that the presence (or potential presence) of police officers in marked cars reduced the likelihood of a crime being committed. It was the first study to demonstrate that research into the effectiveness of different policing styles could be carried out responsibly and safely.

KCPD is the largest city police agency in Missouri, based on number of employees, city population, and geographic area served.

The first black police chief of the KCPD is Darryl Forté who led the KCPD from 2011 to 2017. during his tenure, he sought to rectify racial problems within the department.[8]

From 2017 to 2022, the KCPD was led by Rick Smith, whose tenure was controversial.[9][8] In 2019, when a white officer shot a black man, Smith was heard in a video recording on the scene of the shooting describing the victim as a "bad guy".[9] The white officer was later convicted to six years of prison for involuntary manslaughter and armed criminal action.[9]

Racism

[edit]A 2022 investigation by the Kansas City Star found that there was rampant racism inside the KCPD. Current and former KCPD officers alleged that there was systematic racism and discrimination within the department which forced black officers out of the department.[8]

In 2022, the department had fewer black officers than it did decades ago.[8]

Controversies

[edit]Ryan Stokes killed 2013

[edit]In 2013, Ryan Stokes was fatally shot in the back during a foot chase in the Power and Light District after it was reported that he stole a mobile phone.[10] The officer that fired his weapon was initially awarded a certificate of commendation that was later revoked after it was discovered that some accounts of the incident were inaccurate.[11] A federal court ruled the officer is entitled to qualified immunity from a wrongful death lawsuit filed by the victim's family, as it was judged that the officer concluded he was in imminent danger despite Stokes being unarmed.[12] In 2020, Stokes' family appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court refused to hear the case, and upheld the verdict imposed by the previous court.[13][14] Justice Sonia Sotomayor objected to the decision not to hear the case, writing in her dissent opinion that the case “tells a disturbing story” and "the public is told ‘that palpably unreasonable conduct will go unpunished’ and surviving family members like Stokes’ daughter are told that their losses are not worthy of remedy.”[15]

Cameron Lamb killed 2019

[edit]Cameron Lamb was fatally shot by an officer while reversing his truck into a backyard garage following helicopter reports of a traffic disturbance in 2019. The officer involved was charged with involuntary manslaughter.[16][17]

Black Lives Matter protests 2020

[edit]A viral video in 2020 circulated on Twitter showing KCPD officers assaulting nonviolent protesters, bringing national attention to the department.[18]

Two officers were indicted in 2020 for felony assault committed during an arrest for trespassing that was recorded in a widely shared video.[19][20] The videographer was ticketed and convicted of failure to obey a lawful order after being told to stop recording; he was later pardoned by the mayor.[21]

During the 2020 George Floyd protests, KCPD fired chemical agents, such as pepper spray, at protesters.[22] In wake of these crowd control measures, civil rights groups have called for the resignation of Chief Smith, who defended the officers' actions.[23][24] An activist who was arrested after stepping off the sidewalk is suing the officers who used pepper spray on him and his daughter for excessive force.[25] An officer involved was later charged with misdemeanor assault for spraying pepper spray in the teen's face.[26] Over 150 protesters were arrested during the summer's events and all non-violent charges were dropped by city council ordinance.[27][28]

Shooting of Ralph Yarl and quick release of shooter

[edit]On April 13, 2023, 16-year old Ralph Yarl was shot while mistakenly approaching the home of Andrew D. Lester. Yarl went to the residence thinking it was the correct house to pickup his siblings. The accused shooter, Lester, was detained and released by KCPD hours later, while Yarl was hospitalized. Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas extended his sympathies to Yarl and his family as did Kansas City Police Chief Stacey Graves. Yarl's family retained civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump shortly after the shooting, who stated that there was "no excuse" for the release of the suspect and demanded swift action.[29][30]

On April 17, 2023, 85-year old Andrew Lester was arrested for the shooting. He is charged with armed criminal action and first-degree assault, which is the equivalent of attempted murder in Missouri.[31] The Clay County district attorney stated that there was a "racial component" to the shooting.[32]

Board of Commissioners

[edit] Logo of the Kansas City Police Department | |

| Formation | 1943 |

|---|---|

| Type | Civilian Oversight Board |

| Purpose | To oversee the Kansas City Police Department and set department policy and goals |

| Headquarters | 1125 Locust St. Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

Region served | Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

President-Commissioner | Nathan Garrett |

| Website | Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners |

The Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners is responsible for the operation of the KCPD. The Board sets policy, makes promotions, holds both closed and open meetings and coordinates with the Chief of Police in providing police services to the citizens. Four of the five members of the board are selected by the governor of the state of Missouri, following approval of the Missouri legislature, with the mayor serving as the fifth member. Commissioners serve four year terms, however they serve at the pleasure of the governor and can be replaced.

Rank structure

[edit]The Rank Structure of the Kansas City Missouri Police Department is as follows:

| Title | Insignia |

|---|---|

| Chief of Police | |

| Deputy Chief | |

| Major | |

| Captain | |

| Sergeant | |

| Police Officer | |

| Probationary Police Officer |

Equipment

[edit]The main sidearm used by the KCMO PD is the Glock 22 or Glock 23 both in .40 S&W. Officers also had the choice of choosing the Smith & Wesson Sigma but that is no longer chosen by officers as was the S&W 4026 (Smith & Wesson Model 4006) .40 S&W which had the KCMO PD Badge and KCPD engraved on the slide.[33]

KCPD currently owns and operates three MD 500 helicopters, purchased in 2012.[34] There is a heliport and maintenance facility on Manchester Trafficway, near the Truman Sports Complex. The helicopter unit began in 1967 with three Schweizer S300 rotocraft.

In 2016 a helicopter made an emergency landing on a northeast Kansas City street after experiencing a mechanical problem.[35]

Media

[edit]The Tactical Response Teams of KCPD was featured in A&E's reality series Kansas City SWAT.[36]

The Kansas City, Missouri Police Department has been portrayed in numerous episodes of the television show COPS.

The Homicide Unit of the Kansas City, Missouri Police Department was portrayed in the A&E Network's documentary series entitled The First 48.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- ^ "KCMO.gov". Kcmo.org. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- ^ "KC's new police chief is Deputy Chief Stacy Graves". July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Vowing to work to reduce crime, Stacy Graves is sworn in as Kansas City's police chief". kansascity.

- ^ "History".

- ^ "FAQ: Why Kansas City Doesn't Have 'Local Control' over Its Police Department and How That Could Change". 10 June 2020.

- ^ Greenblatt, Alan (28 August 2013). "After 152 Years, St. Louis Gains Control of Its Police Force". NPR.

- ^ a b c d "Racism in the KCPD: There's no thin blue line for Black officers, Star investigation finds". Kansas City Star. 2022.

- ^ a b c "Kansas City Police Chief Rick Smith announces he will retire in April, after controversial tenure". KCUR 89.3 - NPR in Kansas City. Local news, entertainment and podcasts. 2022-03-25. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ "Community questions 2013 police shooting". 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Award rescinded for officer who fatally shot man". 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Federal court grants KCPD officer immunity in Ryan Stokes shooting". 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Supreme Court rejects appeal in lawsuit brought by Ryan Stokes' family". 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Ryan Stokes - supremecourt.gov".

- ^ "Supreme Court rejects appeal in lawsuit brought by Ryan Stokes' family". 3 July 2023.

- ^ "KC police officer accused in death of Cameron Lamb gets help in defense".

- ^ "KCPD detective charged in Cameron Lamb's shooting". 18 June 2020.

- ^ Waldrop, Theresa (3 June 2020). "Video shows police pepper-spraying a protester. All he seemed to be doing was yelling". CNN. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Cronkleton, Robert A. (19 August 2020). "Two KC police officers plead not guilty in Breona Hill excessive-force arrest case". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Pre-trial conference held Wednesday in Breona Hill case".

- ^ "Kansas City man pardoned after filming woman's arrest that led to KCPD officers indicted". 5 June 2020.

- ^ Cummings, Ian (1 June 2020). "Photo shows Kansas City police officer pepper spray man in face". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Rice, Glenn E. (3 June 2020). "Civil rights groups say Kansas City police chief should resign". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Rice, Glenn E. and Kevin Hardy (3 June 2020). "Jackson County prosecutor is reviewing KCPD officers' use of pepper spray on protester". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Pepper-sprayed protester from viral video Tarence Maddox sues KCPD officers". 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Kansas City Police Officer Charged with Minor Assault During Protests Last Summer". 13 March 2021.

- ^ Moore, Katie (12 March 2021). "Kansas City police officer charged in pepper spray incident during summer protests". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "KC prosecutor dismisses over 200 charges against protesters for non-violent offenses".

- ^ Czachor, Emily Mae (April 17, 2023). "Shooting of Ralph Yarl, teen who mistakenly rang the wrong doorbell, sparks outrage". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ Headlee, Peyton (2023-04-17). "'We are praying for healing,' Hundreds march in support of 16-year-old boy shot after knocking on wrong door". KMBC. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ "565.050". revisor.mo.gov. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ Burnside, Tina; Mossburg, Cheri; Jackson, Amanda (April 17, 2023). "White homeowner accused of shooting Black teen who went to the wrong house in Kansas City will face 2 felony charges, officials announce". CNN. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ Image Reddit

- ^ "Helicopter Unit".

- ^ "KCPD helicopter makes emergency landing". 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Kansas City SWAT | TV Guide". TVGuide.com.