Jumbo

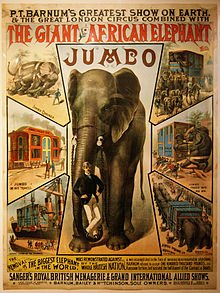

Jumbo and his keeper Matthew Scott(Circus poster, c. 1882) | |

| Species | African bush elephant |

|---|---|

| Sex | Male |

| Born | December 25, 1860[1] Sudan |

| Died | September 15, 1885 (aged 24) St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Various |

| Occupation | Zoo and circus attraction |

| Years active | 1862–1885 in captivity |

| Owner | |

| Weight | 6.15 metric tons (6.78 short tons)[2] |

| Height | 3.23 m (10 ft 7 in);[2] 13 ft 1 in (3.99 m) as promoted by Barnum |

| Cause of death | Railway accident |

Jumbo (December 25, 1860 – September 15, 1885), also known as Jumbo the Elephant and Jumbo the Circus Elephant, was a 19th-century male African bush elephant born in Sudan. Jumbo was exported to Jardin des Plantes, a zoo in Paris, and then transferred in 1865 to London Zoo in England. Despite public protest, Jumbo was sold to P. T. Barnum, who took him to the United States for exhibition in March 1882.

The elephant's name spawned the common word "jumbo", meaning large in size.[3] Examples of his lexical impact are phrases like "jumbo jet", "jumbo shrimp", and "jumbotron". Jumbo's shoulder height has been estimated to have been 3.23 metres (10 ft 7 in) at the time of his death,[2] and was claimed to be about 4 m (13 ft 1 in) by Barnum. "Jumbo" has been the mascot of Tufts University for over one hundred years.

History

[edit]Jumbo was born around December 25, 1860, in Sudan,[1] and after his mother was killed by poachers, the infant Jumbo was captured by Sudanese elephant poacher Taher Sheriff and German big-game poacher Johann Schmidt.[1] The calf was sold to Lorenzo Casanova, an Italian animal dealer and explorer. Casanova transported the animals that he had bought from Sudan north to Suez, and then across the Mediterranean Sea to Trieste.

This collection was sold to Gottlieb Christian Kreutzberg's "Menagerie Kreutzberg" in Germany.[4] Soon after, the elephant was imported to France and kept in the Paris zoo Jardin des Plantes. In 1865, he was transferred to the London Zoo and arrived on 26 June.[5] In the following years, Jumbo became a crowd favorite due to his size, and would give rides to children on his back, including those of Queen Victoria.

While in London, Jumbo broke both tusks, and when they regrew, he ground them down against the stonework of his enclosure.[5] His keeper in London was Matthew Scott, whose 1885 autobiography details his life with Jumbo.[5]

In 1882, Abraham Bartlett, superintendent of the London zoo, sparked national controversy with his decision to sell Jumbo to the American entertainer Phineas T. Barnum of the Barnum & Bailey Circus for £2,000 (US$10,000).[4] This decision came as a result of concern surrounding Jumbo's growing aggression and potential to cause a public disaster. The sale of Jumbo, however, sent the citizens of London into a panic, because they viewed the transaction as an enormous loss for the British empire. 100,000 school children wrote to Queen Victoria begging her not to sell the elephant.[a]

John Ruskin, a fellow of the Zoological Society, wrote in The Morning Post in February 1882: "I, for one of the said fellows, am not in the habit of selling my old pets or parting with my old servants because I find them subject occasionally, perhaps even "periodically," to fits of ill temper; and I not only "regret" the proceedings of the council, but disclaim them utterly, as disgraceful to the city of London and dishonourable to common humanity."[6] Despite a lawsuit against the Zoological Gardens alleging the sale was in violation of multiple zoo bylaws, and the zoo's attempt to renege on the sale, the court upheld the sale.[4] Matthew Scott elected to go with Jumbo to the United States.[5] The London-based newspaper The Daily Telegraph begged Barnum to lay down terms on which he would return Jumbo; however, no such terms existed in the eyes of Barnum.

In New York, Barnum exhibited Jumbo at Madison Square Garden, earning enough in three weeks from the enormous crowds to recoup the money he spent to buy the animal.[4][7] In the 31-week season, the circus earned $1.75M, largely due to its star attraction.[4] On May 17, 1884, Jumbo was one of Barnum's 21 elephants that crossed the Brooklyn Bridge to demonstrate that it was safe, a year after 15 people died during a stampede precipitated by fear that the bridge might collapse.[8] On July 6, 1885, Jumbo was paraded in Saint John, New Brunswick, celebrating his first appearance in Canada.[9]

Death

[edit]

Jumbo died at a railway classification yard in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada, on September 15, 1885. In those days, the circus crisscrossed North America by train. St. Thomas was the perfect location for a circus because many rail lines converged there. Jumbo and the other animals had finished their performances that night, and as they were being led to their box car, a train came down the track. Jumbo was hit and mortally wounded, dying within minutes.[11][12][13]

Barnum told the (possibly fictional) story that Tom Thumb, a young circus elephant, was walking on the railroad tracks and Jumbo was attempting to lead him to safety. Barnum claimed that the locomotive hit and killed Tom Thumb before it derailed and hit Jumbo, and other witnesses supported Barnum's account. According to newspapers, the freight train hit Jumbo directly, killing him, while Tom Thumb suffered a broken leg.[14][15]

Many metallic objects were found in the elephant's stomach, including English pennies, keys, rivets, and a police whistle.[b]

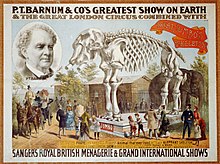

Ever the showman, Barnum had portions of his star attraction separated, to have multiple sites attracting curious spectators. After touring with Barnum's circus,[17] the skeleton was donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where it remains.[18][19] The elephant's heart was sold to Burt Green Wilder of Cornell University, and had been lost by the 1940s.[20] Jumbo's hide was stuffed by William J. Critchley and Carl Akeley, both of Ward's Natural Science, who stretched it during the mounting process; the mounted specimen traveled with Barnum's circus for two years.[17]

Barnum eventually donated the stuffed Jumbo to Tufts University, where it was displayed at P.T. Barnum Hall there for many years. The hide was destroyed in a fire in April 1975.[18] Ashes from that fire, which are believed to contain the elephant's remains, are kept in a 14-ounce Peter Pan Crunchy Peanut Butter jar in the office of the Tufts athletic director, while his taxidermied tail, removed during earlier renovations, resides in the holdings of the Tufts Digital Collections and Archives.[13] Jumbo is the official Tufts University athletic mascot.[21]

Legacy

[edit]Remaining in the United Kingdom are statues and other memorabilia of Jumbo. The elephant – or rather his statuette in the Natural History Museum – was made holotype of Richard Lydekker's proposed subspecies (Loxodonta africana rothschildi) for the large elephants of the eastern Sahel. Modern authorities do not recognize this (or any other subspecies of African bush elephants), considering its purportedly diagnostic large size and peculiarly shaped ears to be individual variation.

While Jumbo's hide resided at Tufts' P.T. Barnum Hall, a superstition held that dropping a coin into a nostril of the trunk would bring good luck on an examination or sports event.[21] Although the hide was destroyed by a major fire,[18] Jumbo remains the mascot of Tufts, and representations of the elephant are featured prominently throughout the campus.[21]

A life-sized statue of the elephant was erected in 1985 in St. Thomas, Ontario, to commemorate the centennial of the elephant's death. It is located on Talbot Street on the west side of the city. In 2006 the Jumbo statue was inducted into the North America Railway Hall of Fame in the category of "Railway Art Forms & Events" as having local significance.[22] St. Thomas's Railway City Brewery sells an IPA beer named Dead Elephant.

Jumbo was the inspiration of the nickname of the 19th-century Jumbo Water Tower in the town of Colchester in Essex, England.[23]

Jumbo is referenced by a plaque outside the old Liberal Hall, now a Wetherspoons pub, in Crediton, United Kingdom.[1]

Lucy the Elephant, a six-story structure in Margate City, New Jersey, was modeled after Jumbo.[24] Built by James V. Lafferty in 1881, Lucy is the oldest surviving roadside tourist attraction in America and a National Historic Landmark. Lafferty also made other Jumbo-shaped structures, including Elephantine Colossus, on Coney Island.[25]

Jumbo has been lionized on a series of sheet-music covers from roughly 1882–83. The four-colour lithograph of Jumbo was created by Alfred Concanen of England, with the music title "Why Part With Jumbo",[c] a song by the lion comique of Victorian British music halls, G. H. MacDermott. It pictured children zoo visitors riding, somewhat precariously, on Jumbo's back. Multiple American lithographic music covers were done, including by J. H. Bufford's Sons.

Canadian folk singer James Gordon wrote the song "Jumbo's Last Ride", which recounts the story of Jumbo's life and death. It is on his 1999 CD Pipe Street Dreams.[27]

Canadian professional ice hockey player Joe Thornton (b. 1979) from St. Thomas, Ontario is nicknamed Jumbo Joe as a homage to Jumbo.[28]

The 1941 animated film Dumbo released by Walt Disney Animation Studios was inspired by the story of Jumbo and is regarded as one of the greatest animated films of all time. Despite the film being fictional, many people have speculated that Jumbo might have been the title character's father.[29]

Examination of Jumbo's skeleton

[edit]

A television program about Jumbo, Attenborough and the Giant Elephant, presented by the naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough, was transmitted on BBC One in the United Kingdom on 10 December 2017.[5] An international team of scientists examined the skeleton and found:

- Jumbo's molar teeth were malformed and out of line as a result of a long-term soft diet that did not wear his molar teeth down enough, obstructing the forward eruptive movement of the next molar.

- Jumbo's nightly rages were probably caused by toothache, rather than musth, as his keeper thought at the time.

- A post mortem photograph of Jumbo shows skin abrasions consistent with an illustration produced just after his death of the freight train hitting him on a hip from behind as he was being led across to his traveling carriage, and said that the likeliest cause of death was internal bleeding from his injuries.

- Examination of Jumbo's limb bones showed overgrown tendon attachment areas consistent with a long-term history of being overloaded at his work.

- Jumbo was still growing at the time of his death, as is normal for African male elephants of his age, and might eventually have attained the size claimed by Barnum.

See also

[edit]- The Greatest Show on Earth, a movie based on the story of the Barnum and Bailey Circus

- History of elephants in Europe

- List of individual elephants

References

[edit]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The Elephant War (1960) by Gillian Avery is a historical novel featuring the protest movement based in Oxford.

- ^ "A postmortem revealed his stomach to contain 'a hat-full' of English pennies, gold and silver coins, stones, a bunch of keys, lead seals from railway trucks, trinkets of metal and glass, screws, rivets, pieces of wire and a police whistle."[16]

- ^ Full title: "Why Part With Jumbo, the Pet of the Zoo"; by: George Barnham (composer); G. H. Macdermott (lyricist); Ernest J. Symons (composer)[26]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Chambers, Paul (2008). Jumbo the greatest elephant in the world (1st US ed.). Hanover, N.H.: Steerforth Press. p. PT14. ISBN 978-1586421533.

- ^ a b c Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950.

- ^ "Jumbo (adj.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "The Life of Jumbo the Elephant" (PDF). St. Thomas Public Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Attenborough And The Giant Elephant". Media Centre. UK: BBC. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Complete works of John Ruskin, Vol 34 Page 560.http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/depts/ruskinlib/stormcloud and http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/depts/ruskinlib/Works%20of%20John%20Ruskin

- ^ "Madison Square Garden I" on Ballpark.com

- ^ McCullough, David (2012). The Great Bridge: the epic story of the building of the Brooklyn Bridge (Updated ed.). London: Simon & Schuster. pp. 431, 543. ISBN 978-1451683233.

- ^ Goss, David (2010). Saint John, 1877-1980. Charleston, SC : Arcadia Pub. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7385-7222-2. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Maeda. "A Portion Of Jumbo The Elephant's Tail At Tufts University". Getty Images. Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Friday January 5, 2018 Full Text Transcript". CBC Radio.

- ^ David Suzuki. "Jumbo: The Life Of An Elephant Superstar". CBC.

- ^ a b Susan Wilson (Spring 2002). "An Elephant's Tale". Tufts Magazine. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015.

- ^ Brennan, Pat (2010-09-08). "Jumbo the elephant leaves a big legend in southern Ontario". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ^ "Jumbo's Death", The Globe, September 17, 1885, p. 1.

- ^ Meredith, Martin (2009). Elephant Destiny: Biography of an Endangered Species in Africa. PublicAffairs. p. 117. ISBN 978-0786728381. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Jumbo: From Our Special Collections". University of Rochester Libraries. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Immolation Of Jumbo", American Heritage, Vol. 26, Issue 6, October 1975.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (22 January 1993). "Barnum's Jumbo Is Back In Museum's Center Ring". New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Guide to the Jumbo the Elephant Material". Cornell Rare Manuscript Collections. 2001. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ a b c "Jumbo the Elephant, Tufts' Mascot". Tufts University. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ The North America Railway Hall of Fame | Inductee: The Jumbo Statue

- ^ "Column: Rev John, Jumbo and another remarkable story in Colchester's history". Gazette. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Ensslin, John C. "Jersey Icons: Lucy the Elephant". northjersey.com. www.northjersey.com. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "The World's Greatest Elephant - Lucy The Elephant". Lucy The Elephant. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- ^ Barnham (Composer), George; MacDermott (Lyricist), G. H.; Symons (Composer), Ernest J. "Why Part With Jumbo, the Pet of the Zoo". Levy Sheet Music Collection. JScholarship. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Jumbo's Last Ride". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Rea, Kyle (July 10, 2010). "St. Thomas honours its hockey hero with banner". St. Thomas Journal. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

The nickname is a homage to Jumbo, the famous elephant killed in St. Thomas 125 years ago.

- ^ "Barnum, Jumbo & Dumbo!". The Barnum Museum. 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2021-05-05.

General and cited references

[edit]- Chambers, Paul. Jumbo: The Greatest Elephant in the World, Andre Deutsch, 2007. ISBN 978-0-233-00222-4

- Harding, Les. Elephant Story: Jumbo and P.T. Barnum Under the Big Top. McFarland, 2000. ISBN 0-7864-0632-1

- Knowles, Sebastian D. G. At Fault: Joyce and the Crisis of the Modern University. The Florida James Joyce Series, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2018. ISBN 978-0-813-05692-0

- McClellan, Andrew. "P. T. Barnum, Jumbo the Elephant, and the Barnum Museum of Natural History at Tufts University," Journal of the History of Collections, Volume 24, Issue 1, 1 March 2012, Pages 45–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhr001

- Nicholls, Henry (11 Nov. 2013). "Jumbo the Elephant: the Afterlife". The Guardian.

- Scott, Matthew (1885). The autobiography of Matthew Scott. Bridgeport, Conn.: Trow's printing and bookbinding Co.

- Sutherland, John. Jumbo: The Unauthorised Biography of a Victorian Sensation, Aurum Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1781312445

External links

[edit]- 1942 photo of the 'stuffed' Jumbo at the Barnum Museum

- Jumbo Images from the PT Barnum Collection at Tufts University

- The Story of Jumbo's Death Archived 2018-06-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Jumbo memorial in St. Thomas, ON, Canada

- Jumbo in typical trade card advertising.

- The North America Railway Hall of Fame

- Autobiography of Matthew Scott, Jumbo's Keeper; also Jumbo's Biography at Faded Page (Canada)

- 1860 animal births

- 1885 animal deaths

- Accidental deaths in Ontario

- Individual African elephants

- Circus animals

- Railway accident deaths in Canada

- Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

- Tufts University

- Individual animals in the United Kingdom

- Individual animals in France

- Individual elephants in the United States