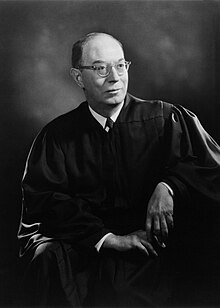

Henry Friendly

Henry Friendly | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Senior Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |||||||||||||

| In office April 15, 1974 – March 11, 1986 | |||||||||||||

| Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |||||||||||||

| In office July 20, 1971 – July 3, 1973 | |||||||||||||

| Preceded by | J. Edward Lumbard | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Irving Kaufman | ||||||||||||

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |||||||||||||

| In office September 10, 1959 – April 15, 1974 | |||||||||||||

| Appointed by | Dwight D. Eisenhower | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Harold Medina | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Ellsworth Van Graafeiland | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born | Henry Jacob Friendly July 3, 1903 Elmira, New York, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Died | March 11, 1986 (aged 82) New York City, U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Suicide by drug overdose | ||||||||||||

| Political party | Republican[1] | ||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Sophie Pfaelzer Stern

(m. 1930) | ||||||||||||

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB) | ||||||||||||

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977) | ||||||||||||

Henry Jacob Friendly (July 3, 1903 – March 11, 1986) was an American jurist who served as a federal circuit judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1959 to 1986, and as the court's chief judge from 1971 to 1973.[2] Friendly was one of the most prominent U.S. judges of the 20th century,[3] and his opinions are some of the most cited in federal jurisprudence.[4][5]

Early life

[edit]Friendly was born in Elmira, New York, on July 3, 1903, the only child of a middle class German-Jewish family.[6] He was descended from Southern German dairy farmers in Wittelshofen, Bavaria, that had adopted the surname of Freundlich. Josef Myer Freundlich (1803–1880), Friendly's great-grandfather, was a prosperous farmer whose estate burned down in 1831; after being denied help by his neighbors because he was Jewish, Josef grew affluent from livestock dealing. Heinrich Freundlich, Friendly's grandfather, immigrated to the United States in 1852 to avoid conscription and anglicised the surname to Friendly. Heinrich worked as a businessman in Cuba, New York, beginning as a peddler. He progressed to own a carriage factory before the birth of Friendly's father, Myer Friendly,[a] who migrated to Elmira in his youth.[8]

Friendly demonstrated precocious abilities in reading and diction at a young age. By age seven, he had an ability to read any book intended for adults. His mother, Leah Hallo, was a serious and reserved bardolater skilled at contract bridge with an excellent memory. She played an intimate role in his upbringing, devoting herself to raising her son and taking him to see evening performances of Gilbert and Sullivan; Friendly later recalled, "there was absolutely nothing she wouldn't have done for me."[9] His father, by contrast, was strict and distant with a penchant for perfection, impressing high standards of work upon him. Their marriage was initially an unhappy one, with Leah leaving at one point to move in with her sister, although Myer eventually persuaded her to return.[10] "We didn't have a very close family," Friendly remembered.[11]

The Friendlys resided in the primarily Christian, western side of Elmira, opposite of the eastern Jewish community. They held various civic positions in town, lived comfortably, and were known as active members of the local German-Jewish population.[12] A monograph in Elmira commemorates Friendly's grandfather, a generous donor to the Jewish community, as "one of the leading men of Elmira in the late nineteenth century."[9] Though not devoutly religious, the family attended a Reform temple alongside other German Jews and held a bar mitzvah for their only son.[13] As he grew older, however, Henry found no redeeming qualities in organized religion.[14]

Friendly was a docile and obedient child who gained a reputation for earnest behavior.[11] Outside of school, he frequented the outdoors, often walking to Mark Twain's study,[b] and visited a great-aunt who played scores of Richard Wagner. He committed himself to reading avidly and enjoyed playing baseball despite being overweight and unathletic. Myer, a sportsman and fisherman, took his son on forays that Henry would ultimately come to reject, which disappointed Myer. Henry also lacked dexterity; after puncturing his hand with a pencil, he lost function of his left-hand little finger and contracted a serious case of blood poisoning. Eye problems developed during boyhood, which would advance to retinal detachment in 1936, further complicated his health. Once they followed into adulthood, surgeries and hospitalizations were complicated necessities.[16]

It was at Elmira that Friendly developed core personal values, learning to value culture and responsibility. He experienced his first serious exposure to law as a young teenager while serving as an expert witness in a breach of warranty trial. By means of a friend's father, a lawyer, he learned to respect law and societal boundaries. However, his reclusivity, combined with a lack of close relationships, contributed to emotional issues that persisted over the course of his life. He made few friends, and the lack of communication with others exacerbated his social awkwardness.[17] Letters written to his mother demonstrated a sincere affection but were aloof, idealistic, and devoid of intimacy.[18]

Education

[edit]

Although he missed periods of school on family vacations, Friendly skipped three grades,[19] taking interests in American history and English literature—namely English writers George Eliot and William Makepeace Thackeray—though avoided science. He was a distinguished student at the Elmira Free Academy, where he was chosen to be valedictorian and editor-in-chief of the academy's newspaper, The Vindex.[20] He admired the local public school system and remembered the "very devoted and dedicated teachers who worked for a pittance."[15] When Friendly graduated in 1919, the scores he attained in the New York Regents Examinations were the highest ever recorded.[15]

At age sixteen, Friendly matriculated at Harvard College, drawn by the school's expansive catalogue. He was a taciturn undergraduate who lacked social skills,[c] yet immersed himself with a focus in history, philosophy, and government, achieving superlative grades every year. He enjoyed the intellectual challenges of understanding history, a pursuit reinforced by Harvard's modern approach that emphasized the field's intellectual and political aspects.[22] Indicating his standing as one of eight top students of the class, Friendly's performance won him election to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. His successes in the classroom were noticed by peers. Classmate Albert Gordon, a future businessman, later reflected upon his reputation: "we thought of him not only as the smartest in the class but the smartest at Harvard College."[23]

A particular interest in European history led Friendly to take courses under prominent scholars Charles Homer Haskins, Archibald Cary Coolidge, and Frederick Jackson Turner.[21] He was exposed to government under president Abbott Lowell,[23] then European diplomatic history under William Langer.[24] In his junior year, he earned second honors for the Bowdoin Prize with a paper examining Italian statesmen Camillo Benso and Giuseppe Garibaldi.[25] Next year, Friendly took inspiration from medievalist Charles Howard McIlwain, whose course in medieval England he credited with being "by all odds the greatest educational experience I had at Harvard College."[26] The historian broadened his knowledge of Latin and stressed the need to interpret documents as they were originally understood, a lesson adopted by Friendly when he ascended to the bench years later.[27] A paper for McIlwain's course, "Church and State in England under William the Conqueror," won Friendly first place for the Bowdoin Prize and recognition among the faculty, who told him it could easily be accepted as a doctoral dissertation.[28] History professor Frederick Merk, who judged one exam answer given by Friendly as worthy of publication in an academic journal, assured him of an appointment to the university's faculty.[29] He graduated first in his class in 1923, summa cum laude, "importuned to continue on for a doctorate."[30]

Postgraduate years

[edit]Studies in Europe

[edit]Inspired by McIlwain, Friendly contemplated an academic life.[31] He intended to pursue a Ph.D. in medieval history after graduation, confounding his parents' wishes for him to enroll in Harvard Law School. After Harvard awarded Friendly a prestigious Shaw traveling fellowship for abroad study, he notified his parents of his ambitions for a doctorate; both parents then steered connections to contact Judge Julian Mack,[d] informing him "about this dreadful thing that was about to occur."[33] Following his recommendation, they arranged for Friendly to meet law professor Felix Frankfurter with the aim of dissuading him from pursuing a career in history. Frankfurter convinced Friendly to follow through the fellowship, which enabled postgraduate studies in Europe for a year,[e] then tentatively attend the Law School.[35][f]

From 1923 until 1924, Friendly sojourned in Europe. He witnessed the alarming inflation and social unrest that grappled the Weimar Republic, then traveled to Amsterdam and thirdly to Paris, where he attended the École pratique des hautes études for a few months, presenting a French paper on 14th century parliament. He found the lectures on law there unimpressive, admitting that "between the two, I much preferred history...if anything could give one a distaste for law that was it."[36] After stopping in Italy, his studies led him to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England. With the year "moderately successful" though still "somewhat dissatisfied," Friendly returned to the United States and entered Harvard Law School.[37]

Law school

[edit]In 1925, Harvard Law School was a growing institution which expanded to house 1,440 students. Under dean Christopher Columbus Langdell, the school devised the "case method" of teaching which concentrated on actively engaging students in a Socratic dialogue. On his very first day at the Law School, Friendly made a tangible impact that built his confidence and recognition.[38] In one lecture, Manley Ottmer Hudson, his torts professor, asked in what language an early English case was written. After students guessed wrongly, Hudson then prompted Friendly, who successfully identified it as archaic Law French. A skeptical Hudson went to the archives and produced the original medieval text, which Friendly proceeded to translate for the class. "So that really made my reputation at the Harvard Law School, on the first day," he recalled.[39][g]

Although he was not enrolled in any of his classes, Friendly was frequently invited by Frankfurter to join him. The professor made the young student one of his favorites, and it was due to Frankfurter that Friendly grew interested in federal jurisdiction and emerging field of administrative law. Other professors, struck by Friendly's command over the material, praised his ability.[41] They included Thomas Reed Powell, a proponent of legal realism, as well as formalists Samuel Williston and Joseph Beale, who often had to contend with novel theories by Zechariah Chafee and Roscoe Pound.[42] After one examination, Calvert Magruder, Friendly's first-year teacher in contract law, left him a congratulatory note: "[I have] never run across as beautiful [an exam] book as yours in Contracts... [nor one with your] sense of values and emphasis, the logical construction of your answers, your compactness & facility of expression."[43]

Friendly finished first in his class his first year and was honored as a member of the Harvard Law Review. He was elected the journal's president his second year,[h] writing to his parents, "it is certainly the greatest honor in the Law School, except for the Fay Diploma—which is awarded at the end of three years, and I am particularly gratified in that very few Jews have ever held the office."[45] Never before had he worked harder than during his time on the Law Review. With Herbert Brownell Jr., the editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal, he drafted the first edition of The Bluebook.[46]

Along with the existing commitments to the law review, Friendly was an active member of the Ames Moot Court Competition, where he won the Marshall Prize for its best brief. Despite investing less time to schoolwork, he also came first in his class his second year.[47] That summer, he received an invitation from Frankfurter, who was teaching at Columbia Law School, to join him in New York City. Frankfurter had been living there with Emory Buckner; feeling that teaching would not sufficiently occupy him, he arranged for Friendly, along with classmates James Landis and Thomas Corcoran, to room together in the city. The group would make acquaintances with distinguished jurists Learned Hand, Augustus Noble Hand, Julian Mack, and Charles Culp Burlingham. After Buckner requested the assistance of two "bright young men," Frankfurter sent Friendly and Corcoran to aid him with his prosecution of Harry Daugherty at the New York U.S. Attorney's office.[48]

In 1927, Friendly graduated as class president with an LL.B., summa cum laude.[49] His academic record was the best in the history of the school, with the achievements he amassed earning him a "legendary" status that became "part of the lore of the university."[50] Every honor the school had to offer was bestowed upon him.[51] He achieved the highest numerical average of any Harvard Law student in the 20th century,[52] and was the first graduate of the university to receive his law degree with summa distinction.[i][51] The Fay Diploma,[j] the Law School's most distinguished decoration, was also awarded to him,[57] as was both Sears Prizes, given usually to two who achieved the highest first and second year grades.[58] Even though his performance suggested otherwise, Friendly found his experience at Harvard Law School unrewarding. He thought highly of the case method but rarely enjoyed the faculty instruction. Criminal law, taught by Pound, bored him, as did Beale. "After a few thrilling months with Williston and Hudson at the beginning of the first year, everything seemed to slide," he wrote to Frankfurter.[59] For the rest of his life, Friendly seriously doubted his decision choosing law over history.[60]

Clerkship under Brandeis

[edit]

In Friendly's second year, Frankfurter notified him of his decision to appoint him as a law clerk to Justice Louis Brandeis on the Supreme Court.[61] Brandeis was aware of Friendly's intellectual achievements at Harvard; both he and Frankfurter foresaw a career for Friendly in the legal academy.[61] In Friendly's third year, Frankfurter changed course. He suggested that Friendly delay the clerkship to remain at Harvard for a fourth year to study, teach, and research for him.[62] Friendly declined, tired of law school. Buckner advised him to immediately proceed to the clerkship then be a practitioner.[63] The competing interests of Brandeis, Frankfurter, and Buckner struggled over the future of Friendly's career, quarreling over a life in the academy or in the private practice of law.[64][k] Ultimately, Friendly forewent a postgraduate year.[65] He decided to begin with Brandeis in the fall after graduation, and traveled to Washington, D.C., where a front-page story by The Christian Science Monitor described their association as "the two highest Harvard Law men to work together."[66]

The clerkship with Brandeis had a lasting impact on Friendly.[67][l] He admired the justice's encyclopedic knowledge of the law and held a deep respect for his intellect.[66] Brandeis, who spent long, isolated hours away from his clerk working, championed judicial restraint and often chose to defer to the legislatures.[69] Both obsessed over issues of federal jurisdiction, with Friendly helping Brandeis to avoid decision on those grounds as a "jurisdiction hound."[70] He recalled that Brandeis would think autonomously to form his own opinions: "neither bitter personal attack nor temporary defeat could shake Brandeis’ faith in the future, provided men would continue to fight."[69]

Playing important roles in complicated cases under Brandeis would aid Friendly in private practice and as a judge.[69] Notwithstanding the little time they spent together, both he and the justice viewed each other highly.[71] Brandeis, in a telephone with Frankfurter, declared, "If I had another man like Friendly, I would not have to do a lick of work myself."[68] Friendly praised Brandeis as knowing "more law than almost the rest of the Court together" and titled him as "an absolutely superb technician: really the best in cases like complicated Interstate Commerce Commission cases."[72] The most prominent case of the term had been Olmstead v. United States (1928), challenging government wiretapping, in which Friendly convinced the justice to remove from his dissent an erroneous passage which described television as being able to "peer into the inmost recesses of the home."[73] He would be among Brandeis's most highly ranked clerks, along with Dean Acheson, Paul Freund, and Willard Hurst.[74] When he left, Brandeis wrote Frankfurter regarding Irving Goldsmith, Friendly's replacement: "Goldsmith will have a hard time as the successor to Friendly."[75]

Private practice

[edit]While still a clerk for Brandeis, Friendly received an offer to be an associate professor at Harvard Law School, which the justice pressed him to accept, as he often wished for his clerks to enter academia or public life. Between a choice to assume the professorship or enter private practice, Friendly chose the latter, becoming an associate in the prominent white-shoe law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner, Howland & Ballantine (now Dewey Ballantine) in September 1928.[76] He was willing to sacrifice pay for a career in history, though did not share the same enthusiasm for legal scholarship and declined to be a professor. He had also explored the possibility of joining the Interstate Commerce Commission but became determined to work privately in New York. A practice in law offered independence and financial stability, qualities which he yearned.[77]

Elitism and antisemitism had been pervasive in law firms. His record at Harvard Law School made him a natural candidate for any New York firm, but antisemitism undermined Friendly's choices.[79] Root, Clark was among the few firms in Wall Street to hire Jews in addition to having a Jewish partner, a characteristic which attracted him: "it was the only place in New York that a Jew could get a job."[80] He interviewed also at Sullivan & Cromwell, which also permitted Jews, though turned down an offer after undergoing a series of interviews, suspecting them to be predicated on antisemitic beliefs and due only to his having been president of the Harvard Law Review.[81]

For 31 years, Friendly stayed in private practice, where his speciality evolved into a combination of administrative, common-carrier, and appellate law.[82][83] After passing the New York bar in 1928, the reputation he developed during his years as an attorney from 1928 to 1959 proved outstanding.[1] He had begun in September 1928 at Root, Clark, where he eventually was made a partner on January 2, 1937.[84][2]

The firm first assigned him as an assistant to Grenville Clark, a senior partner who had suffered a nervous breakdown, with the intent that Friendly's aid and experience might reinvigorate him. Clark had been a prominent corporate lawyer, a fellow graduate of Harvard Law School, and nominee of the Nobel Peace Prize.[85] Friendly's assistance, however, failed to improve his health. After months of uneventful work under Clark, Elihu Root Jr.[m] reassigned Friendly to a case representing Pan American-Grace Airways and its president, Juan Trippe. Friendly would assume control of the company's legal affairs with Root's consent not long afterward, primarily tasked with handling its contracts and diplomatic relationships. In 1929, he began a romantic relationship with Sophie Stern, daughter of future Judge Horace Stern, and the couple married on September 4, 1930.[87] It was his first serious relationship with a woman.[88]

In 1931, Brandeis once again urged Friendly to join the faculty of Harvard Law School, this time with the additional support of Frankfurter, Roscoe Pound, Calvert Magruder, and Edward Morgan. When Friendly refused in order to remain in private practice, Brandeis and Frankfurter attempted to get him to join the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) as its assistant general counsel the next year at the invitation of Eugene Meyer. He turned down this office also, a decision which came as a disappointment to Frankfurter.[89] The Law School continued to make repeated requests for Friendly to join its faculty, all of which were ultimately unsuccessful.[90]

From 1931 until 1933, John Marshall Harlan II, a senior associate[91] at Root, Clark, was embroiled with a case representing the will of the late heirless Ella Virginia von Echtzel Wendel. Wendel, a wealthy recluse who was the sole owner of about $100 million of real estate,[92] left a substantial fortune of $40–50 million to unknown next of kin. Hundreds of claimants—many fraudulent—arose to inherit a part of the estate. Friendly was a prime assistant to Harlan, proving false the claim of a prominent candidate, and whose extensive research into the claimant's forgeries led to the dissolve of several other parties' cases.[93] He would recall of the case:

John Harlan and I often remarked to each other that the Wendel Estate litigation was the most enjoyable forensic experience of our lives. It combined the elements of drama with—what is not always available—the financial resources needed to do a thoroughly professional job.[94]

Pan Am and Cleary, Gottlieb

[edit]Friendly was responsible for Pan Am's congressional affairs, spending much of his time in Washington, D.C., litigating contracts. He accompanied Trippe in his role as a legal advisor and sat adjacent to him in conference meetings. During World War II, Pan Am underwent rapid expansion, some of which were facilitated by Congressional funds appropriated in an agreement to use the company's airfields as a staging ground for the war effort. Friendly and Pan Am lawyer John Cobb Cooper sought to gain an advantage over the U.S. Department of War in dictating its terms—their effective efforts later came under scrutiny in a Senate investigation led by Missouri Senator Harry S. Truman, one which ultimately found no wrongdoing.[95]

With fellow associate Leo Gottlieb, Friendly began considering leaving Root, Clark to start a new firm. The two left in 1945, forming Cleary, Gottlieb, Friendly & Cox (now Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton),[n] and were joined by a number of the firm's associates and partners.[97] The departure of a substantial portion of its lawyers caused a serious split in Root, Clark; though the firm was damaged, it left on good terms with the newly formed Cleary, Gottlieb.[98] Cleary, Gottlieb's immediate success dispelled Friendly's initial financial fears amidst a declining postwar economy.[99]

Friendly brought Pan Am and New York Telephone to the new firm. In 1946, the former appointed Friendly as its general counsel and vice president, a position he would serve in until 1959.[100][101] In working for both Cleary, Gottlieb and Pan Am simultaneously, he was split between commuting to the firm in Wall Street and the Pan Am headquarters located in the Chrysler Building. Cleary, Gottlieb grew quickly, and it would attract high-profile clients such as Bing Crosby, Albert Einstein,[102] the French government, and Sherman Fairchild. George W. Ball, who had joined the firm at its invitation, left to serve as United States Under Secretary of State and, later, United States Ambassador to the United Nations. Elihu Root Jr. and Grenville Clark, formerly of Dewey, Ballantine, resigned their positions to join Cleary, Gottlieb as of counsel.[103]

While working for Pan Am, Friendly proved himself to be a skilled litigator, adept in cross-examination. In a case involving the company, Trans World Airlines (TWA), and American Overseas Airlines (AOA),[104] Friendly's cross-examination of multiple airline executives revealed contradictory statements which were refuted by internal data. On one occasion, his employment of a sometimes aggressive, unapologetic approach in questioning led to an objection by counsel, though Friendly refused to recant his methods. The case, which concerned Pan Am's acquisition of the AOA,[105] also involved James M. Landis, former Dean of Harvard Law School, who had a personal feud with both Friendly and Trippe; Landis represented the TWA in its efforts to compete against Pan Am for the purchase of the AOA. Friendly's cross-examination of Landis led to the upholding of Pan Am's acquisition by the Civil Aeronautics Board, and President Harry Truman's signed approval on July 10, 1950, unexpectedly gave Pan Am the benefit of additional access to airways which it did not ask for. TWA appealed the controversial decision by Truman to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which in turn upheld Friendly's arguments and struck down the appeal.[106]

The majority of Friendly's appellate litigation would be in the service of Pan Am, though in 1956 he won a New York Court of Appeals case for the New York Telephone Company against the Public Service Commission. He also successfully distinguished himself in oral argument at the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, where he argued before Judge Calvert Magruder, who had previously been among those to recommend Friendly to join the Harvard Law faculty. In 1959, Trippe approached Friendly to strike a contract with Howard Hughes for the purchase of six Boeing jets. With Raymond Cook,[107] Hughes' lawyer, Friendly's efforts to clear the contract ensured its survival amidst a bond issue with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The $40 million deal was one of the hastiest Friendly drafted and would be one of his last acts in private practice.[108]

Nomination to the Second Circuit

[edit]Upon the election of President Dwight D. Eisenhower's in 1952, Friendly sought a possible judicial appointment. Decades of having been in private practice had begun to take a toll on his mental health; cases for Pan Am before the CAB grew monotonous and unsatisfying. Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr., with whom Friendly worked with during his days at Harvard Law, began searching for potential candidates to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. It was recommended that Friendly take up a preliminary appointment on the district court, but he eschewed a position, having previously attended it as a disappointed spectator.[109]

I think there have been not more than two occasions during the long period I have served as a judge when I have felt it permissible to write a letter in favor of anyone for judicial appointment. However, I feel so strongly that the Second Circuit would be greatly benefitted by the appointment of Mr. Henry J. Friendly that I cannot forbear writing you to express my hope that you may see fit to fill the vanacy now existing in the Circuit by selecting him. I have not the slightest doubt that as a Circuit Judge he would be an addition to our court, as great as, if not greater than, anyone else you could choose; not only because of his unblemished reputation and high scholarship, but because of his balanced wisdom and wide outlook.

Friendly's performance in private practice bore little influence on his being a viable candidate. His specialized practice in administrative law was known only to a select group of fellow lawyers in New York, and he had appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court twice, losing both cases. Additionally, the legal bouts against Landis and TWA received limited media coverage, nor was he an active member of academia, having turned a career as a professor down years prior. He was primarily distinguished by his exceptional performance at Harvard Law School, his clerkship for Justice Brandeis, and the reputation he accrued during his years in practice.[111]

In 1954, John Marshall Harlan II was appointed by Eisenhower to the U.S. Supreme Court to replace Justice Robert Jackson, leaving his position on the Second Circuit vacant. Felix Frankfurter and Learned Hand soon emerged as vocal supporters of Friendly to fill the seat, though ultimately the position went to J. Edward Lumbard. Friendly lobbied friends, colleagues, and close aides—including Louis M. Loeb and State Senator Thomas C. Desmond—in the case another vacancy arose. The unexpected development of a cataract in his left eye nearly endangered his candidacy, though symptoms abated following a successful eye surgery.[112] He was once again passed over when Judge Jerome Frank died in 1957. In spite of Frankfurter's vehement support for Friendly, Frank's seat was filled by Leonard P. Moore.[113]

On October 23, 1957, Brownell Jr. resigned as Attorney General and was replaced by William P. Rogers,[114] who soon received letters from Frankfurter when Judge Harold Medina announced his retirement in January 1958. The Association of the Bar of the City of New York supported Friendly's candidacy to take Medina's seat and the American Bar Association appraised him as "exceptionally well qualified."[115] The candidates to fill the seat of Medina also included Irving Kaufman, who had the bipartisan backing of both the state's Democrats and prominent Republicans, which Friendly lacked. Kaufman attempted to reinforce his platform by seeking the additional endorsement of Learned Hand, but Hand avoided doing so, using his law clerk, Ronald Dworkin, as a means of evading a potential meeting. In 1959, political support shifted towards Friendly as a compromise candidate and he was further bolstered by a public endorsement by Learned Hand soon after. On March 10, 1959, Eisenhower nominated Friendly to the U.S. Senate, a move praised by The New York Times and The Washington Post.[116] Frankfurter's voiced support to Minority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson, who in turn convinced Senator Thomas Dodd to send the hearing notice, ensured Friendly's confirmation on September 9.[117]

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

[edit]Friendly received his commission to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals on September 10, 1959.[100] He was 56 years old.[118] Justice John Marshall Harlan II swore him in on September 29, 1959, at the United States Courthouse (now the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse) in Manhattan.[119] Friendly joined just four other active judges on the court: Chief Judge Charles Edward Clark, alongside the conservative Lumbard, liberal Sterry R. Waterman, and the more conservative Leonard P. Moore. They were of similar age, experience, and party. Both Lumbard and Moore had been Wall Street lawyers with service as U.S. attorneys, and the former was especially conservative in matters of criminal law. The fact that they never met in person to discuss cases contributed to Friendly's feeling that the court lacked a sense of mutual respect and intellectual discourse.[120]

Despite his initial reservations, Friendly established himself as being complaisant and sensitive to his colleagues, incorporating suggestions from the other judges whenever possible.[121] Lumbard was elevated to chief judge towards the end of the year, and the Court's efficiency and affability improved.[122] Former Connecticut congressman J. Joseph Smith was Eisenhower's final appointment, arriving in 1960.[120] Present but inactive judges included senior Harold Medina, and the celebrated but aged Learned Hand.[123] Friendly came to accept Hand, who attended periodically before dying in 1961, as beyond his prime years.[123] Though formidable, the Court was less respected than it had been under Hand's tenure, when its composition included Augustus Hand and Jerome Frank.[122]

Friendly was apprehensive about his judicial ability and was initially beset by self-doubt in writing opinions. He first arrived on the bench on October 6, 1959, and erroneously ruled in favor of the government in United States v. New York, New Haven & Hartford R.R. The case, which was on appeal, concerned the Interstate Commerce Commission and fell under the Expediting Act, which in turn required the case to bypass the court of appeals directly to Supreme Court.[124] Wary of another mistake, Friendly began taking a strictly literal interpretation of laws. Regarding his indecisiveness over one decision, he told Learned Hand of his fears; Hand exclaimed, "Damn it, Henry, make up your mind. That's what they're paying you to do!"[125]

He would continue to serve as a judge for the rest of his life, assuming senior status on April 15, 1974. He served as a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States, where he was its chief judge from 1971 to 1973, and was also a presiding judge of the Special Railroad Court from 1974 to 1986. His judicial service was terminated on March 11, 1986, due to his death.[100]

During his tenure, Friendly would pen over 1,000 judicial opinions while remaining active as a scholarly writer.[126] He wrote extensively in law reviews, publishing works that were considered seminal in multiple fields and extraordinary in combination with his existing workload as an appellate judge.[127][6]

Legacy

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

In a ceremony following Friendly's death, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said, "In my 30 years on the bench, I have never known a judge more qualified to sit on the Supreme Court." At the same ceremony, Justice Thurgood Marshall called Friendly "a man of the law."[128] In a letter to the editor of The New York Times following Friendly's obituary, Judge Jon O. Newman called Friendly "quite simply the pre-eminent appellate judge of his era" who "authored the definitive opinions for the nation in each area of the law that he had occasion to consider."[5] In a statement after Friendly's death, Wilfred Feinberg, the 2nd Circuit's chief judge at the time, called Friendly "one of the greatest Federal judges in the history of the Federal bench."[5] Judge Richard A. Posner described Friendly as "the most distinguished judge in this country during his years on the bench" and "the most powerful legal reasoner in American history."[129][5] Akhil Amar called Friendly the greatest American judge of the 20th century. Amar also cited Friendly as a major influence on Chief Justice John Roberts.[130]

Honors

[edit]Friendly was a member of the Harvard Board of Overseers from 1964 to 1969, and was also a member of the executive committee of the American Law Institute. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Award in Law in 1978.[131] He was awarded numerous honorary degrees, including a Doctor of Laws by Northwestern University in 1973, and a Doctor of Humane Letters and LL.D. from Harvard.

Harvard Law School has a professorship named after Friendly. Paul C. Weiler, a Canadian constitutional law scholar, held it from 1993 to 2006;[132] William J. Stuntz, a scholar of criminal law and procedure, held it from 2006 until his death in March 2011.[133] The professorship is currently held by Carol S. Steiker, a specialist in criminal justice policy and capital punishment.[134] The Federal Bar Council awarded Friendly a Certificate of Distinguished Judicial Service posthumously in 1986.[135] The Henry J. Friendly Medal, established by the American Law Institute, was named in memory of Friendly and endowed by his former law clerks;[136] Justice Sandra Day O'Connor received the award in 2011.[137]

Personal life

[edit]Friendly was a member of the Republican Party.[138][139][140]

Family and marriage

[edit]Sophie Pfaelzer Stern, Friendly's wife, was a member of a Philadelphia Jewish family and educated at Swarthmore College and Fordham University. Following their marriage, the newly-wed couple traveled to Italy and Paris for their honeymoon.[141] Both Friendly and Stern shared a close relationship, and they had two children—David and Joan—by January 1937 and a third, Ellen, soon after.[142] As their marriage progressed, it became complicated and grew unintimate later in his life.[143]

Work engrossed Friendly, and he had a largely estranged relationship with his children, seeing them only during the summer.[144] He was also extremely reserved, showed both little emotion and signs of physical affection to his children, and was uninterested in their personal affairs. He sought to maintain an excessively formal environment, often retiring to study alone.[145] Joan Friendly Goodman, his second-eldest child,[146][147] remembered Friendly's tentative bond:

What he experienced he had difficulty expressing and because he expressed so little the feelings never were shaped, modulated, refined. . . . I knew what he wanted, but couldn't express himself [...] He was slightly gruff, too loud, used his voice rather than a caress to wake me, but I knew it was his way of saying I want to care for you. I saw the intent behind the deed when the gesture failed. He was always on the verge of giving vent to tenderness but, except in his letters, rarely able to do so.[148]

Health

[edit]Friendly was a natural pessimist and demonstrated some symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder. He harbored feelings of hopelessness in addition to experiencing bouts of extreme sadness, though not to the extent of impairing his diligence.[149]

Friendly's father, Myer, died at age 76 on December 28, 1938,[150] in a local hospital at St. Petersburg, Florida; he was a longtime winter resident in the city.[151][o] His father's death of a blood clot precipitated Friendly's lifelong fear of a stroke and concern for his own health.[152] Friendly's wife died of cancer in 1985.[153]

Death

[edit]After Sophie's death from colon cancer on March 11, 1985, Friendly began to think seriously about committing suicide. Her death had been unexpected; she had been healthy and vigorous, while he had always been pessimistic and burdened with health issues. Friendly died by suicide at age 82 on March 11, 1986, in his Park Avenue apartment in New York City;[139] multiple prescription bottles were at his side.[154] Police said they found three notes in the apartment: one addressed to his resident maid and two unaddressed notes. In all three notes, Friendly talked about his distress at his wife's death, his declining health and his failing eyesight, according to a police spokesman.[139] They had been married for 55 years. He was survived by a son and two daughters.[139]

Law clerks

[edit]Throughout Friendly's tenure on the Second Circuit, competition among third-year law students to be selected as one of his law clerks was intense. Besides a clerkship on the Supreme Court, a Friendly clerkship was the most coveted. For his first eight years on the bench, the judge hired exclusively from Harvard Law School, later taking students from other law schools based on the recommendation of professors.[155]

Extrajudicial writings

[edit]Books

[edit]- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1, 1962). The Federal Administrative Agencies: The Need for a Better Definition of Standards. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674295506.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1967). Benchmarks. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226265308.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1968). "Remarks by Judge Henry J. Friendly". In Sutherland, Arthur E. (ed.). The Path of Law from 1967. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674657854.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1971). The Dartmouth College Case and the Public-Private Penumbra. Vol. 12. University of Texas Press. ASIN B0006C3JQY. LCCN 71-627370.

- Schwartz, Bernard; Wade, H. W. R. (1972). Legal Control of Government: Administrative Law in Britain and the United States. Foreword by Henry J. Friendly. Oxford University Press (Clarendon). ISBN 978-0019825313.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1973). Federal Jurisdiction: A General View. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231037419.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1975). "Grenville Clark: Legal Preceptor". In Dimond, Mary Clark; Cousins, Norman; Clifford, J. Garry (eds.). Memoirs of a Man: Grenville Clark. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393087161.

Journals

[edit]- Friendly, Henry J. (February 1928). "The Historic Basis of Diversity Jurisdiction". Harvard Law Review. 41 (4): 483–510. doi:10.2307/1330049. JSTOR 1330049.

- Friendly, Henry J. (March 1932). "Review of The Interstate Commerce Commission by I. L. Sharfman, Vols. I, II". Harvard Law Review. 45 (5): 941–945. doi:10.2307/1332048. JSTOR 1332048.

- Friendly, Henry J. (November 1934). "Some Comments on the Corporate Reorganizations Act". Harvard Law Review. 48 (1): 39–81. doi:10.2307/1331740. JSTOR 1331740.

- Friendly, Henry J. (November 1935). "Review of The Interstate Commerce Commission by I. L. Sharfman, Part III. Volume A". Harvard Law Review. 49 (1): 163–166. doi:10.2307/1333250. JSTOR 1333250.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1936). "Amendment of the Railroad Reorganization Act". Columbia Law Review. 36 (1): 27–59. doi:10.2307/1116239. JSTOR 1116239.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1937). "Review of Brandeis: The Personal History of an American Ideal by Alfred Lief". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 85 (3): 330–332. doi:10.2307/3309092. JSTOR 3309092.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1939). "Review of Chapter Ten: Corporate Reorganization under the Federal Statute by Luther D. Swanstrom". Harvard Law Review. 52 (3): 540–542. doi:10.2307/1334371. JSTOR 1334371.

- Friendly, Henry J. (March 1939). "Review of A Treatise on Aviation Law by Henry G. Hotchkiss". Harvard Law Review. 52 (5): 860–862. doi:10.2307/1333462. JSTOR 1333462.

- Friendly, Henry J. (November 1940). "Review of La Responsabilité Civile Dans les Transports Aériens Intérieurs et Internationaux by Jean van Houtte". Harvard Law Review. 54 (1): 169–171. doi:10.2307/1333389. JSTOR 1333389.

- Friendly, Henry J.; Tondel Jr., Lyman M. (1940). "Relative Treatment of Securities in Railroad Reorganizations under Section 77". Law & Contemporary Problems. 7 (3). Duke Law School: 420–437. doi:10.2307/1189702. JSTOR 1189702.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1943). "Review of International Air Transport and National Policy by Oliver James Lissitzyn". Harvard Law Review. 56 (4): 656–659. doi:10.2307/1334437. JSTOR 1334437.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1947). "Review of Brandeis: A Free Man's Life by Alpheus Thomas Mason". The Yale Law Journal. 56 (2): 423–426. doi:10.2307/793018. JSTOR 793018.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1960). "Mr. Justice Brandeis: The Quest for Reason". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 108 (7): 985–999. doi:10.2307/3310209. JSTOR 3310209.

- Friendly, Henry J. (April 1960). "A Look at the Federal Administrative Agencies". Columbia Law Review. 60 (4): 429–446. doi:10.2307/1120305. JSTOR 1120305.

- Friendly, Henry J. (December 1961). "Reactions of a Lawyer Newly Become Judge" (PDF). The Yale Law Journal. 71 (2): 218–238. doi:10.2307/794327. JSTOR 794327.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1961). "Review of The Common Law Tradition Deciding Appeals by Karl N. Llewellyn". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 109 (7): 1040–1056. doi:10.2307/3310673. JSTOR 3310673.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1961). "Review of The Law and Its Compass, 1960 Rosenthal Lectures, Northwestern University School of Law by Cyril J. Radcliffe". Journal of Legal Education. 14 (2). Association of American Law Schools: 275–277. JSTOR 42891433.

- Friendly, Henry J. (December 1962). "Judge Learned Hand: An Expression from the Second Circuit". Brooklyn Law Review. 29 (1): 6–15.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1962). "The Federal Administrative Agencies: The Need for Better Definition of Standards". Harvard Law Review. 75 (7): 1263–1318. doi:10.2307/1338547. JSTOR 1338547.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1963). "The Gap in Lawmaking—Judges Who Can't and Legislators Who Won't". Columbia Law Review. 63 (5): 787–807. doi:10.2307/1120530. JSTOR 1120530.

- Friendly, Henry J. (August 11, 1963). "Review of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes—The Proving Years, 1870–1882 by Mark de Wolfe Howe". The New York Times Book Review.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1964). "Mr. Justice Frankfurter and the Reading of Statutes". In Mendelson, Wallace (ed.). Felix Frankfurter, the Judge. Reynal & Hitchcock. ASIN B00178T5I2.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1964). "In Praise of Erie—And of the New Federal Common Law". New York University Law Review. 39 (3): 383–422.

- Friendly, Henry J. (October 1965). "The Bill of Rights as a Code of Criminal Procedure" (PDF). California Law Review. 53 (4): 929–956. doi:10.2307/3478984. JSTOR 3478984.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Winter 1965). "On Entering the Path of the Law". University of Chicago Law School Record. 13 (1). University of Chicago Law School: 17–22.

- Friendly, Henry J. (August 1965). "Satisfaction, Yes — Complacency, No!". American Bar Association Journal. 51 (8): 715–720. JSTOR 25723310.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1965). "Mr. Justice Frankfurter". Virginia Law Review. 51 (4): 552–556. JSTOR 1071549.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1965). "Review of The Courts, the Public and the Law Explosion by Harry W. Jones, ed". New York Law Forum. 11. New York Law School.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1965). "Review of The Commission and the Common Law: A Study in Administrative Interpretation by Arnold H. Bennett". Syracuse Law Review. 16.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Summer 1966). "Review of The American Jury by Harry Kalven, Jr., Hans Zeisel, Thomas Callahan, Philip Ennis". University of Chicago Law Review. 33 (4): 884–889. doi:10.2307/1598515. JSTOR 1598515.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1967). "The Idea of a Metropolitan University Law School". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 19 (1): 7–16.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Fall 1968). "The Fifth Amendment Tomorrow: The Case for Constitutional Change". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 37 (4): 671–726.

- Friendly, Henry J. (November 1968). "The 'Limited Office' of the Chenery Decision". Administrative Law Review. 21 (1). American Bar Association: 1–9. JSTOR 40691094.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1968). "Review of The Unpublished Opinions of Mr. Justice Brandeis by Alexander Bickel, ed". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 106 (5): 766–769. doi:10.2307/3310388. JSTOR 3310388.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1968). "Review of Anatomy of the Law by Lon L. Fuller". Duquesne Law Review. 7.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1969). "A Federal Court of Administrative Appeals?". Case & Comment. 74. Rochester, New York.

- Friendly, Henry J. (April 1969). "Chenery Revisited: Reflections on Reversal and Remand of Administrative Orders". Duke Law Journal. 1969 (2): 199–225. doi:10.2307/1371428. JSTOR 1371428.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Winter 1969–70). "Time and Tide in the Supreme Court". Connecticut Law Review. 2 (2): 213–221.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Autumn 1970). "Is Innocence Irrelevant? Collateral Attack on Criminal Judgments". University of Chicago Law Review. 38 (1): 142–172. doi:10.2307/1598963. JSTOR 1598963.

- Friendly, Henry J. (December 1971). "Mr. Justice Harlan, as Seen by a Friend and Judge of an Inferior Court". Harvard Law Review. 85 (2): 382–389. JSTOR 1339738.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1970). "Judicial Control of Discretionary Administrative Action". Journal of Legal Education. 23 (1). Association of American Law Schools: 63–69. JSTOR 42892042.

- Friendly, Henry J. (September 1971). "Review of Learned Hand's Court by Marvin Schick". Political Science Quarterly. 86 (3). Oxford University Press: 470–476. doi:10.2307/2147916. JSTOR 2147916.

- Friendly, Henry J. (October 24, 1972). "Remarks of Chief Judge Friendly". In Memoriam: Honorable John Marshall Harlan. Washington, D.C.: Proceedings of the Bar and Officers of the Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 13–17.

- Friendly, Henry J. (March 1972). "Judge Paul R. Hays". Columbia Law Review. 72 (3): 445–446. doi:10.2307/1121408. JSTOR 1121408.

- Friendly, Henry J. (March 1972). "The "Law of the Circuit" and All That". St. John's Law Review. 46 (3): 406–413.

- Friendly, Henry J. (September 1972). "Review of History of the Supreme Court of the United States by Paul A. Freund; Vol. I: Antecedents and Beginnings to 1801 by Julius Goebel Jr.; Vol. VI: Reconstruction and Reunion, 1864-88, Part One by Charles Fairman". Political Science Quarterly. 87 (3). Oxford University Press: 439–447. doi:10.2307/2149210. JSTOR 2149210.

- Friendly, Henry J. (June 1973). "Erwin N. Griswold—Some Fond Recollections". Harvard Law Review. 86 (8): 1365–1368. JSTOR 1340027.

- Friendly, Henry J. (January 1973). "Review of Judgments: Essays on American Constitutional History by Leonard W. Levy". Columbia Law Review. 73 (1): 179–182. doi:10.2307/1121345. JSTOR 1121345.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1973). "Empirical Approaches to Judicial Behavior: Of Voting Blocs, and Cabbages and Kings". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 42 (4): 673–678.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1973). "The United States Courts of Appeals 1972–73 Term—Criminal Law and Procedure" (PDF). Georgetown Law Journal (Preface). 62 (2): 401–403.

- Friendly, Henry J. (April 1974). "Averting the Flood by Lessening the Flow". Cornell Law Review. 59 (4): 634–657.

- Friendly, Henry J. (April 1974). "New Trends in Administrative Law". Maryland Bar Journal. 61 (3): 9–16.

- Friendly, Henry J. (June 1975). "Some Kind of Hearing". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 123 (6): 1267–1317. doi:10.2307/3311426. JSTOR 3311426.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1975). "Edward Weinfeld, The Ideal Judge". New York University Law Review. 50.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1976). "Review of Administrative Law by Bernard Schwartz". New York University Law Review. 51.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1976). "Review of Police Discretion by Kenneth Culp Davis". University of Chicago Law Review. 44 (1): 255–259. doi:10.2307/1599266. JSTOR 1599266.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1976). "The Federal Courts". N.Y.U. Bicentennial Conference of American Law.

- Friendly, Henry J. (May 1977). "Federalism: A Foreword" (PDF). The Yale Law Journal. 86 (6): 1019–1034. doi:10.2307/795701. JSTOR 795701.

- Friendly, Henry J. (November 1, 1978). "The Courts and Social Policy: Substance and Procedure". University of Miami Law Review. Meyer Lecture Series. 33 (1): 21–42.

- Friendly, Henry J. (June 1978). "In Praise of Herbert Wechsler". Columbia Law Review. 78 (5): 974–981. doi:10.2307/1121888. JSTOR 1121888.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1980). "Review of Administrative Law Treatise by Kenneth Culp Davis". Hofstra Law Review. 8 (2): 471–484.

- Friendly, Henry J. (March 1981). "Thoughts about Judging". Michigan Law Review. 79 (4): 634–641. doi:10.2307/1288287. JSTOR 1288287.

- Friendly, Henry J. (Fall 1982). "Indiscretion About Discretion". Emory Law Journal. 31 (4): 747–784.

- Friendly, Henry J. (June 1982). "The Public-Private Penumbra—Fourteen Years Later". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 130 (6): 1289–1295. doi:10.2307/3311971. JSTOR 3311971.

- Friendly, Henry J. (July 1983). "Ablest Judge of His Generation". California Law Review. 71 (4): 1039–1044. JSTOR 3480188.

- Friendly, Henry J. (1985). "From a Fellow Worker on the Railroads". Tulane Law Review. 60 (2): 244–255.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ President of the Friendly Boot and Shoe Company.[7]

- ^ Twain's octagonal study, located in Elmira, was his place of work for Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. The writer had married Olivia Langdon Clemens, a native of Elmira, and the two owned a house in the town. After her death, Twain no longer inhabited his Elmira retreat.[15]

- ^ Future mathematician Marshall Stone, a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon and a classmate, never encountered him during the college's social events.[21]

- ^ Mack was a Jewish judge Leah had met in Chicago.[32]

- ^ The Shaw traveling fellowship allowed a student 14 months of study in European universities.[34]

- ^ Frankfurter reasoned he could study "medieval history, civil law, or nothing at all" during the fellowship, then leave to study medieval history should he dislike the experience.[32]

- ^ Friendly would later learn that Frankfurter had orchestrated Hudson's questioning beforehand.[40]

- ^ Friendly was president of Volume 40 of the Harvard Law Review during the 1926–1927 term. The following year, he was succeeded by Erwin Griswold, whom he mentored, for Volume 41.[44]

- ^ Justice Louis Brandeis graduated from Harvard Law School in 1877 with approximately a 95 average, compared to Friendly's average of 86. Comparatively, a student who received an 80 average was expected to be first in their class with highest honors.[53] However, in the 46 years between Brandeis' and Friendly's tenure at the law school, the university had changed its grading system. Friendly biographer David M. Dorsen notes "some controversy over whether Friendly or Brandeis had the highest average in the history of the law school."[54] Once adjusted for the changes in the grading system, Friendly's academic record was higher than that of Brandeis, and thus the highest in the law school's history.[55]

- ^ Awarded based on the law student with the highest combined grade point average during the three years of study.[56]

- ^ Frankfurter saw Buckner's intrusion as obstructing the true purpose of the clerkship: to prepare Friendly for academia.[63] The professor wrote to Buckner, "What surprises me about all the lawyers with whom Friendly talked in New York, and even about your comments to him, is that you did not treat Friendly as a very special case—a man of truly extraordinary talents, under no pressure of immediacies, still very young and potential of very great things in all sorts of ways.... Don't you think it is terribly important that there be deposited in an unusually talented person like Friendly thoughts and reflections, not merely with reference to his success in New York during the next five or ten years, but that he should keep in mind what would equip him for the rest of his life as a civilized, reflective mind, with a deep inner life, instead of becoming as narrow and as sterile as are all but a negligible few of the leading members of the present day bar?"[64]

- ^ Friendly placed Brandeis highest in his rating of judges—above both Learned Hand and Frankfurter—later in his life.[68]

- ^ Son of 41st U.S. Secretary of War and 38th U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root. He was the principal founder of Root, Clark & Bird (expanded later to Root, Clark, Buckner, Howland & Ballantine).[86]

- ^ When Friendly became a founding partner of the firm, the firm's title would also be changed to Cleary, Gottlieb, Friendly, Steen & Hamilton, "the name most remember."[96]

- ^ Myer left a sizeable inheritance to his children and relatives upon his death. Among them, Friendly received the largest share at $305,156.[150]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kahn 2003, p. 274.

- ^ a b Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1721.

- ^ Margolick, David (April 24, 1992). "An Unusual Court Nominee, Judging by His Family". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Davis 2012, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d Newman, Jon O. (March 24, 1986). "From Learned Hand To Henry Friendly". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Davis & Gladden 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Kahn 2003, p. 273.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 1, 5–6.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 6–7.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 5–6, 8.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 8–9.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 59, 140.

- ^ a b c Dorsen 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 6, 9–10.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 10–12.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Hare, Jim (November 16, 2019). "Elmira History: EFA grad went on to have a distinguished career on the federal bench". Star-Gazette. Elmira, NY. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 9–10; Keeffe 1968–1969, p. 316; Keeffe 1961, p. 319.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 11–14.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1716.

- ^ "HONORARY MEMBERS OF HARVARD PHI BETA KAPPA: Chapter Honors Louis A. Coolidge and Several Professors—New Members in Course". The Boston Globe. June 19, 1922. p. 4. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 13–17.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 16–17.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, pp. 1715–1716; Dorsen 2011, p. 602; Boudin, Dorsen & DeJulio 2013, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 13; Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1715; Dorsen & Peppers 2021, p. 240.

- ^ Boudin, Dorsen & DeJulio 2013, p. 169–170.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1168.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 20; Siegel 2017, p. 116.

- ^ "YOUTH WINS HIGH HONORS: Henry Friendly of St. Petersburg Is Graduated from Harvard". St. Petersburg Times. August 9, 1923. p. 9. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 20–21.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1168–1169.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 20–24; Davis 2012, p. 342; Boudin, Dorsen & DeJulio 2013, p. 170.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1169.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Boudin, Dorsen & DeJulio 2013, p. 170.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 23–24.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1720.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 25, 71.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 1, 24; Lucas 2017, pp. 430–431

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 25; Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1717.

- ^ "WON HARVARD'S FIRST LLB SUMMA CUM LAUDE: Henry J. Friendly of Elmira, N Y, Had Marvelous Record in College and Law School". The Boston Globe. June 24, 1927. p. 14. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Davis & Gladden 2014, p. 64; Dorsen 2012, p. xiii; Harvard Law Review 1986, pp. 1713, 1716; Kahn 2003, p. 273; Leval 2012, p. 258; Boudin 2007, p. 977; Siegel 2017, pp. 116, 126.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1170.

- ^ Subrahmanyam, Divya (November 26, 2012). "A conversation on the legal legacy of Judge Henry Friendly". Harvard Law Today. Harvard Law School. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Brains—Both Have Plenty: U. S. Supreme Court Gets Harvard Law School's Two Best Scholars". The Columbia Record. Columbia, South Carolina. September 28, 1927. p. 6. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 27, xiii.

- ^ Lichtman, Steven B. (2012). "Review of Henry Friendly: Greatest Judge of His Era". Law and Politics Book Review. 22 (10): 499–502.

- ^ Caplan, Lincoln (January–February 2016). "Rhetoric and Law: The double life of Richard Posner, America's most contentious legal reformer". Harvard Magazine. Harvard University. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "Over 200 Undergraduates Gain Honors in Graduation Awards: Number of Degrees Awarded Is Largest Ever—Law School for First Time Gives Summa". The Harvard Crimson. Harvard University. June 23, 1927. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Snyder 2022, p. 67.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, pp. 1716–1717; Snyder 2010, p. 1169.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1169; Dorsen 2012, p. 27.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1171.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 26.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1172.

- ^ a b Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1717.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1717–1718.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, pp. 28–29; Snyder 2010, pp. 1174–1175.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1189–1190.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Dorsen 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1179.

- ^ Lucas 2017, p. 431.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 28–29; Lucas 2017, p. 431.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 29–30.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1175.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1177.

- ^ Dorsen & Peppers 2021, p. 240; Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1721.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 31–32, 34.

- ^ Siegel 2017, p. 124.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1191.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1191–1192.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 32–33.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 34, 81.

- ^ Boudin, Dorsen & DeJulio 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 34, 44.

- ^ Clifford, John Garry. "Clark, Grenville (1882-1967)". Harvard Square Library. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Elihu Root Jr., Lawyer, Is Dead; Statesman's Son a Civic Leader; Arts Patron and Yachtsman Received Truman Medal — Leading La Guardia Backer". The New York Times. August 28, 1967. p. 31. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 32, 34–37.

- ^ Dorsen & Peppers 2021, p. 241.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1718.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 37–38; Siegel 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 34.

- ^ "Ella Wendel Dies; Last of Her Family: Huge Realty Holdings Valued at $100,000,000 Are Left With No Kin to Claim Them". The New York Times. March 15, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 38–41.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 47–48, 60.

- ^ Dorsen & Peppers 2021, p. 240.

- ^ "Henry Friendly Partner in New Law Firm". Star-Gazette. January 5, 1946. p. 3. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ "George Cleary, 90, Law Firm Founder". The New York Times. March 27, 1981.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 50–52.

- ^ a b c Henry Friendly at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1712.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 60, 66–67.

- ^ "Debate An Air Merger: The CAB Hears Attorneys For Two Lines". The Kansas City Times. March 2, 1950. p. 23. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Overseas Airline Dispute Aired". Albuquerque Journal. March 2, 1950. p. 19. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 61–66.

- ^ "Hughes Tool Co, Divests Itself Of Northeast Airline Holdings; Miami Lawyer Is Nominated for 3 Fears as Trastee of Slock in the Carrier". The New York Times. October 8, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 67–69.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 71–72.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 75; Gunther 1994, p. 650.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 72–73; Lucas 2017, p. 433

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 73.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 73–74.

- ^ "Mr. Brownell Resigns". The New York Times. October 25, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1201.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, pp. 74–77; Gunther 1994, pp. 651–652.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1713.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 85.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 114–115.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 84, 115.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 114.

- ^ a b Dorsen 2012, p. 115.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 82–83.

- ^ Brecher 2014, p. 1181.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (June 10, 1986). "A Solemn Tribute To Henry Friendly, A Quiet Giant Of The Appeals Bench". The New York Times.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. xiii.

- ^ Akhil Amar (June 29, 2021). "Amarica's Constitution: Know the Nine You Will". PodBean (Podcast). Publisher. Event occurs at 31:30. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Harvard Law Review 1986, p. 1721–1722.

- ^ "Paul C. Weiler, Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law, Emeritus". Harvard Law School. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ "William J. Stuntz". Harvard Law School. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ "Carol S. Steiker". Harvard Law School.

- ^ Metro Datelines (November 27, 1986). "Honors for 4 Judges And Ex-Prosecutor". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ "Henry J. Friendly Medal". The American Law Institute. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "Law school's namesake, Justice O'Connor, receives Friendly Medal". ASU News. October 21, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 75, 242, 250.

- ^ a b c d Norman, Michael (March 12, 1986). "Henry J. Friendly, Federal Judge In Court Of Appeals, Is Dead At 82". The New York Times.

- ^ Grunwald, Michael; Goldstein, Amy (July 24, 2005). "Few have felt beat of Roberts's political heart". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 36–37, 44.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 56.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 44, 57.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 53–55.

- ^ Goodman 1984, p. 10.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 57.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 53–54.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 52–54, 342.

- ^ a b "M.J. Friendly Estate Valued At $530,028". Star-Gazette. February 16, 1940. p. 3. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "M. H. Friendly Succumbs Here: Winter Resident of City 19 Years". St. Petersburg Times. December 29, 1938. p. 2. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 44.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Elkin, Larry (March 11, 1986). "Veteran Appeals Court Judge Found Dead With Suicide Note". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Dorsen 2012, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Dorsen 2012, p. 361.

- ^ a b c d Dorsen 2012, p. 362.

- ^ a b c d Dorsen 2012, p. 363.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dorsen 2012, p. 364.

- ^ a b c d Dorsen 2012, p. 365.

- ^ a b c d e Dorsen 2012, p. 366.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gunther, Gerald (1994). Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-58807-0.

- Kahn, Ronald (2003), "Henry Jacob Friendly (1903–1986)", in Vile, John R. (ed.), Great American Judges: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, Santa Barbara: ABC–CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-989-8

- Nelson, William E. (Fall 2006). The Legalist Reformation: Law, Politics, and Ideology in New York, 1920–1980. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5504-1.

- Dorsen, David M. (2012). Henry Friendly, Greatest Judge of His Era. Foreword by Richard Posner. Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674064935. ISBN 9780674064935. S2CID 159335898.

- Posner, Richard A. (October 7, 2013). Reflections on Judging. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674725089.

- Boudin, Michael (2013). "Judge Henry Friendly and the Mirror of Constitutional Law". In Dorsen, Norman; DeJulio, Catherine (eds.). The Embattled Constitution. New York, NY: New York University Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814770122.001.0001. ISBN 9780814770122.

- Domnarski, William (2016). Richard Posner (1st ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199332311.

- Biskupic, Joan (2019). The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465093274.

- Dorsen, David M. (2021). "Clerking for a Giant: Henry Friendly and His Law Clerks". In Peppers, Todd C. (ed.). Of Courtiers and Princes: Stories of Lower Court Clerks and Their Judges. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813944609. OCLC 1225548992.

- Snyder, Brad (August 23, 2022). Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment. New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-1324004875.

Journals

[edit]- Keeffe, Arthur John (March 1961). "Practicing Lawyer's guide to the current Law Magazines". American Bar Association Journal. 47 (3): 319–320. JSTOR 25721532.

- Keeffe, Arthur John (1968–1969). "In Praise of Joseph Story, Swift v. Tyson and "The" True National Common Law". American University Law Review. 18 (2).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Leventhal, Harold (June 1975). "Federal Jurisdiction: A General View". Columbia Law Review (Review). 75 (5): 1009–1019. doi:10.2307/1121560. JSTOR 1121560.

- Currie, David P. (1984). "On Blazing Trials: Judge Friendly and Federal Jurisdiction". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1): 5–9.

- Wisdom, John Minor (1984). "Views of a Friendly Observer". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1): 63–77.

- Goodman, Frank (1984). "Judge Friendly's Contributions to Securities Law and Criminal Procedure: "Moderation is All"". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1).

- Pollak, Louis H. (1984). "In Praise of Friendly". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1): 39–62.

- McGowan, Carl (December 1984). "The Judges' Judge". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1): 34–38. JSTOR 3311861.

- Boudin, Michael (December 1984). "Memoirs in a Classical Style". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 133 (1): 1–4.

- Ackerman, Bruce A.; Feinberg, Wilfred; Freund, Paul; Griswold, Erwin N.; Loss, Louis; Posner, Richard A.; Rakoff, Todd (June 1986). "In Memoriam: Henry J. Friendly". Harvard Law Review. 99 (8): 1709–1727. JSTOR 1341207.

- Gewirtz, Paul (1986–1987). "Commentary: A Lawyer's Death" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 100 (2053): 2053–2056. doi:10.2307/1341200. JSTOR 1341200.

- Irene Merker Rosenberg, Irene; Rosenberg, Yale L. (December 1991). "Guilt: Henry Friendly Meets the MaHaRaL of Prague". Michigan Law Review. 90 (3): 604–625. doi:10.2307/1289465. JSTOR 1289465.

- Sachs, Margaret V. (January 1997). "Judge Friendly and the Law of Securities Regulation: The Creation of a Judicial Reputation". Southern Methodist University Law Review. 50 (3): 777–823.

- Randolph, A. Raymond (April 1999). "Administrative Law and the Legacy of Henry J. Friendly" (PDF). New York University Law Review. 74 (1): 1–17.

- A. Raymond Randolph (2006). "Before Roe v. Wade: Judge Friendly's Draft Abortion Opinion" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. 29 (3): 1035–1062.

- Breen, Daniel (2007). "Avoiding Wild Blue Yonders: The Prudentialism of Henry J. Friendly and John Roberts". South Dakota Law Review. 52 (1): 73–135.

- Boudin, Michael (October 2007). "Madison Lecture: Judge Henry Friendly and the Mirror of Constitutional Law" (PDF). New York University Law Review. 82 (4): 975–996.

- Peppers, Todd C. (2009). "Isaiah and His Young Disciples: Justice Brandeis and His Law Clerks". Journal of Supreme Court History. 34 (75): 75–97. doi:10.1353/sch.2009.0022.

- Snyder, Brad (December 8, 2010). "The Judicial Genealogy (and Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts". Ohio State Law Journal. 71 (1149). SSRN 1722362.

- Boudin, Michael (December 2010). "Judge Henry Friendly and the Craft of Judging". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 159 (1): 1–15. JSTOR 41039020.

- Domnarski, William (July 2011). "The Correspondence of Henry Friendly and Richard A. Posner 1982-86". The American Journal of Legal History. 51 (3): 395–416. doi:10.1093/ajlh/51.3.395. JSTOR 41345371.

- Dorsen, David M. (2011). "Judges Henry J. Friendly and Benjamin Cardozo: A Tale of Two Precedents". Pace Law Review. 31 (2): 599–626. doi:10.58948/2331-3528.1778.

- Boudin, Michael (2012). "Friendly, J., Dissenting". Duke Law Journal. 61 (4): 881–901. JSTOR 41353736.

- Davis, Frederick T. (2012). "On Becoming a Great Judge: The Life of Henry J. Friendly" (PDF). Texas Law Review. 91 (8): 339–343.

- Leval, Pierre N. (2012). "Remarks on Henry Friendly: On the Award of the Henry Friendly Medal to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor" (PDF). The Green Bag. 15 (257).

- Coombs, Mary I. (2012). "Henry Friendly: The Judge, the Man, the Book" (PDF). Texas Law Review. 91 (331): 331–345.

- Edelman, Peter (2012). "Henry Friendly: As Brilliant as Expected but Less Predictable" (PDF). Texas Law Review. 91 (331): 345–351.

- Brecher, Aaron P. (2014). "Some Kind of Judge: Henry Friendly and the Law of Federal Courts". Michigan Law Review. 112 (6).

- Snyder, Brad (2014). "The Former Clerks Who Nearly Killed Judicial Restraint" (PDF). Notre Dame Law Review. 89 (5): 2129–2154.

- Sippel, Richard L. (December 2014). "Review of Henry Friendly: Greatest Judge of His Era by David M. Dorsen" (PDF). The Federal Lawyer: 76–82.

- Davis, John J.; Gladden, Lesley B. (2014). "The Bill of Rights as a Code of Criminal Procedure: Judge Henry Friendly's Prescient Prediction" (PDF). Cumberland Law Review. 45 (9): 63–90.

- Dorf, Michael C. (Autumn 2016). "Divergent Paths: The Academy and the Judiciary [Review]". Journal of Legal Education. 66 (1). Association of American Law Schools: 186–202. JSTOR 26402426.

- Lucas, Tory L. (June 20, 2017). "Henry J. Friendly: Designed to Be a Great Federal Judge". Drake Law Review. 65 (422). SSRN 2989733.

- Siegel, Andrew M. (2017). "The Myth of Merit: The Garland Nomination, the Friendly Legacy, and the Slipperiness of Appellate Court Qualifications". Savannah Law Review. 4 (1): 113–128.

- Witt, John Fabian (2017). "Adjudication in the Age of Disagreement". Fordham Law Review. 86 (1): 149–162.

- Bloomfield, Alan (2017). "Review of Henry Friendly: Greatest Judge of His Era by David M. Dorsen". The Oral History Review. 44 (1): 138–140. doi:10.1093/ohr/ohw086. JSTOR 26427537.

- Joshi, Ashish; Breyer, Stephen (Winter 2017). "A Report from the Front: An Interview with Justice Stephen G. Breyer". Litigation. Beyond Borders. 43 (2). American Bar Association: 17–22. JSTOR 26402033.

- Halper, Thomas (December 30, 2019). "Henry Friendly and the Incorporation of the Bill of Rights". British Journal of American Legal Studies. 8 (2): 236–247. doi:10.2478/bjals-2019-0012.

External links

[edit]- Henry Jacob Friendly at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Reminiscences of Henry Jacob Friendly 1960 — Columbia University

- Merrick Garland receives the 2022 Henry J. Friendly Medal

- Remarks on Henry Friendly on the award of the Henry Friendly Medal to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor

- 1903 births

- 1986 suicides

- 1986 deaths

- 20th-century American judges

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- Law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- People from Elmira, New York

- Lawyers from New York City

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Suicides in New York City

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower

- People associated with Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton