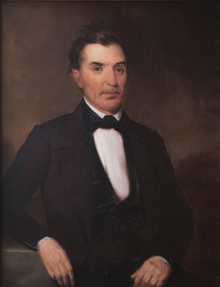

Jourdan Saunders

Jourdan Saunders | |

|---|---|

| Born | Jourdan Michaux Saunders 1796 |

| Died | March 19, 1875 (aged 79) Near Warrenton, Virginia, US |

| Partner | Mary Wilkins |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Romulus Mitchell Saunders (half-brother) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | Tennessee militia |

| Years of service | 1814–1815 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 2nd Regiment of Mounted Gunmen |

| Conflict | |

Jourdan Michaux Saunders (1796 – March 19, 1875) was an American domestic slave trader and farmer, noted for his partnership with Franklin & Armfield. Born to a slave-owning family in Caswell County, North Carolina, his father died soon after a move to Smith County, Tennessee, leaving Saunders with a significant inherited estate. As a young man during the War of 1812, he volunteered in the Tennessee militia, seeing service at the Battle of New Orleans. He entered the slave trade in October 1827 as part of a business partnership with David Burford, founding the firm J. M. Saunders and Company and choosing Fauquier County, Virginia as a base of operations.

After significant early losses, he was able to impress Isaac Franklin after a successful New Orleans sale, and entered into a business affiliation with Franklin & Armfield. Saunders was tasked with acquiring slaves to be shipped to Louisiana. Following a wave of legislation restricting interstate trading in the aftermath of Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion, Franklin & Armfield and their associates managed to circumvent Louisiana trade restrictions, resulting in considerable profits. Saunders ultimately shipped hundreds of enslaved people to Franklin & Armfield, although he fell into financial difficulties as the firm entered large amounts of debt and became temporarily unable to reimburse Saunders. He withdrew from the industry over the mid-to-late 1840s, retiring to his Fauquier County estate alongside his mixed-race mistress, Mary Wilkins, and their four children. He never legally recognized his children as his own, although all except James (who had served in the Colored Troops during the Civil War) received his inheritance. In March 1875, Saunders died of heart disease at his estate.

Early life

[edit]Jourdan Saunders was born in early 1796 to William and Nancy Cunningham Saunders, slave-owners from Caswell County, North Carolina. He had three older half-siblings from his father's previous marriage, including future congressman Romulus Mitchell Saunders, and two younger siblings. Soon after his birth, his family moved to what would become Smith County, Tennessee. His father died in 1803, dividing his property among his wife and children. Jourdan inherited around 175 acres (71 ha) of land and several slaves. Nancy Saunders remarried to Richard Alexander several years later.[1]

Military service

[edit]During the later stages of the War of 1812, he enrolled in the Tennessee militia.[2] On September 20, 1814, he enrolled in the 2nd Regiment of Mounted Gunmen at Dixon Springs under Colonel Thomas Williamson. He was mustered at Fayetteville in October and served for seven months, seeing service as a private in John Coffee's brigade in the Battle of New Orleans. He was discharged in April 1815.[3]

Slave trade

[edit]J. M. Saunders and Company

[edit]

In late October 1827, Saunders and David Burford began a business partnership, founding a slave-trading firm named J. M. Saunders and Company.[4][5] Burford, primarily occupied by political work in Smith County, Tennessee, provided advice and capital for the operation, with Saunders actively purchasing and transporting slaves.[5][6] After several months of scouting locations, Saunders chose Fauquier County, Virginia, renting an office in the county seat of Warrenton. He began purchasing slaves in late May 1828, paying commission fees to agents who searched the rural countryside for slave sales. Saunders himself traveled to Winchester for further slave purchases. By July, he had acquired a total of 22 slaves, including men, women, and children, kept in the Old Fauquier County Jail after payments by Saunders.[7]

Saunders began his first journey to the Deep South in mid-July 1828, intending to sell the 22 people in southern Louisiana. The slaves were forced to walk alongside Saunders' carriage handcuffed or tied together over the 1100 mile journey. He had timed his arrival considerably earlier than most other traders, intending to beat other traders to the market. However, he arrived in Louisiana in late August or September, several months prior to the main slave trading season, which peaked in the winter following the end of harvest. He recorded no sales in New Orleans, the main trading hub of the region, and likely sold the slaves on credit to sugar planters in rural parishes of the state. Saunders was ultimately able to sell all but one slave (who absconded) but likely lost considerable amounts of money on the venture.[8]

In 1829, Saunders switched to transporting slaves by sea to New Orleans. He purchased 16 slaves in the late summer and autumn; one man managed to escape and go into hiding, while another cut off much of his hand with an axe while attempting to escape from a tree he had been tied to by Saunders. Saunders and 14 slaves traveled to Louisiana aboard the brig United States, departing from Alexandria, Virginia and reaching Louisiana in mid-November. The whereabouts of the escaped slave had been discovered the day before setting sail, and Saunders hired agents to attempt to capture the fugitive in order to recuperate some of his continued financial losses. Soon after arriving in Virginia, he was able to sell seven young slaves for a considerable profit to Isaac Franklin of Franklin & Armfield, the largest slave-trading firm in the country. He was able to collect debts owed in Louisiana and sell the remainder of his ten slaves to various buyers in St. Mary Parish, leaving the company with a $10,000 (equivalent to $290,000 in 2023) profit.[9][10]

Affiliation with Franklin & Armfield

[edit]Soon after Saunders finished his sales in Louisiana, Saunders purchased a total of 26 additional slaves from Franklin, and was able to make a significant profit by selling them across rural Louisiana. Franklin, seeing him as a skilled and reputable trader, approached him on a business partnership. Under the terms of the agreement, Franklin would manage sales at New Orleans and Natchez, his partner John Armfield would handle shipping from Alexandria, while Saunders would focus on acquiring additional slaves in Virginia. Saunders was one of 7 or 8 affiliates of Franklin & Armfield in the broader Chesapeake region.[11]

Saunders' sales continued to expand. Franklin was able to quickly sell slaves acquired by Saunders, grossing over $18,000 (equivalent to $520,000 in 2023) in the 1830–1831 season. However, sales had begun to decline, with Franklin writing to Saunders in the spring of 1831 that "times are extremely dull, indeed much worse than I ever saw them in my life."[12] Despite Franklin urging caution, Saunders continued making large purchases of slaves, having sent 17 slaves to Franklin & Armfield by September 1831.[13]

Bypassing trade restrictions in Louisiana

[edit]

Fear of revolts following Nat Turner's 1831 slave rebellion sparked a wave of slave regulations. The Louisiana State Legislature outlawed the interstate slave trade in November 1831, allowing only limited exceptions, such as for planters permanently moving to Louisiana alongside their slaves. Shortly prior to the law taking effect, John Armfield had met with Saunders and several other agents in a self-described "Council of War" in Alexandria, laying the groundwork for a plan to bypass the new legislation through legal loopholes and fraudulent bills of sale. By falsifying receipts and financial documentation, the company passed off sales made in Louisiana as ones made in Virginia or Tennessee. Slaves were also sold "at sea", with buyers in New Orleans purchasing the slaves while the ship was en route, thereby introducing their own property into the state, outlined in the legislation as a legal exception.[14]

The scheme was successful. Saunders earned a massive profit, used to purchase enslaved people in Virginia at deflated prices. The Louisiana market had been largely abandoned by other slave traders, especially smaller operations. Franklin & Armfield and their associates were able to violate the Louisiana legislation and create a significant windfall, capitalized on by Saunders. Armfield himself reported that he was "much pleased with the passage of the law."[15][16] Before the New Orleans operations were largely abandoned in favor of Natchez, Saunders had sent 68 slaves to the region, without any real competition. Although Saunders continued business relations with his initial partner Burford, he no longer needed to rely on his funding. Saunders refused to accept Burfords' requests for slaves for his personal plantation, writing that doing so would likely upset his connections with Franklin & Armfield.[17]

Setbacks and withdrawal from business

[edit]Although the following seasons were less lucrative, Saunders continued to profit from a booming slave market. Significant plantation expansion following the Indian removal and the Trail of Tears led to large purchases of slaves. Additionally, an active banking sector allowed for easy access to loans, increasing the number of farmers able to acquire slaves. While a corresponding rise in competition in Virginia slave trading increased prices, the growing demand in the Deep South kept the industry profitable. Saunders shipped around a hundred individuals during the 1832–1833 season.[18][16]

Saunders initially dismissed Burford's claims in October 1832 of cholera outbreaks and slave deaths among coffles, but a significant cholera epidemic spread across the South over the following months, leading to the deaths of nine enslaved people, including four children, and significantly reduced profit for the company. In April 1833, Saunders purchased an acre lot in central Warrenton, likely serving as an office and residence, as well as a holding pen for slaves. He had purchased and shipped around 100 people during the 1833–1834 season, stopping only when he had exhausted his cash reserves.[19]

By late 1834, Franklin & Armfield had entered over $100,000 (equivalent to $2,860,000 in 2023) in debt, and had become completely unable to supply a cash settlement to Saunders. He refused offers of payment in the form of loans, instead opting to continue partnership with the company for another year in hopes of repayment. Saunders scaled down operations, purchasing only 15 slaves for the company in the fall of 1834. Armfield, also wishing to leave the industry, cancelled his partnership with Saunders in December 1834. A final payment to Saunders, worth around $10,000 (equivalent to $290,000 in 2023) was considerably delayed, and likely delivered in a mixture of cash and commercial paper. Saunders would occasionally consider re-entering the trade, but in 1847 would attest that he had not purchased slaves since 1840.[20]

Later life and death

[edit]A supporter of Andrew Jackson since the early 1830s,[21] Saunders continued his support for the Democratic Party throughout the 1840s, serving in county government and chairing local Democratic conventions.[22]

Saunders began a relationship with Mary Wilkins (b. 1815) in the early 1840s, recording her as a "housekeeper" on census forms. Although marked as white on the 1860 US census, she registered as a Free Negro in 1847 and was recorded as "nearly white". Saunders and Wilkins had four children together: James (b. 1843), Frank (b. 1845), Sallie (b. 1847), and Lillie Saunders (b. 1854).[23][24] In 1851, they moved to a large 186-acre property several miles outside of Warrenton, a grain farm Saunders named Mountain View.[25] During the American Civil War, his oldest son James fled the South due to Unionist sentiments. He later joined the Union Army as part of the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment, before returning to Virginia after the war to work on the family farm.[26]

Jourdan Saunders died of heart disease at his farm in Fauquier County on March 19, 1875.[27][28] Saunders never formally acknowledged his children as his own, although most received some money from inheritance. Arrangements were made for his daughters to inherit his farm after Mary's death. James Saunders received no inheritance whatsoever.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 231.

- ^ Clay, Robert Y. (Fall 1999). "War of 1812 Pension Records: Jourdon M. Saunders". Smith County Historical Society Newsletter. 11 (4): 127–128.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 232.

- ^ a b Purcell 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 234.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 232–234.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 235–238.

- ^ Jones, William D. (Fall 2021). "Beyond New Orleans: Forced Migrations To, From, and In Louisiana, 1820–1860". Louisiana History. 62 (4): 445. JSTOR 27095320.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 242.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 243–244.

- ^ a b Sublette 2015, p. 484.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 246–248.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 248–252.

- ^ Sublette 2015, p. 460.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 253.

- ^ Fauquier County, Virginia register of free negroes, 1817–1865. Midland, Virginia: Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County. 1993. p. 128.

- ^ Rothman 2022, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 254.

- ^ Rothman 2022, p. 255.

- ^ a b Rothman 2022, pp. 254–256.

- ^ "Obituary". Alexandria Gazette. March 29, 1875. p. 2. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Purcell, Aaron D. (Summer 2005). "A Spirit for Speculation: David Burford, Antebellum Entrepreneur of Middle Tennessee". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 64 (2): 90–109. JSTOR 42631252.

- Rothman, Joshua D. (May 2022). "The American Life of Jourdan Saunders, Slave Trader". Journal of Southern History. 88 (2): 227–256. doi:10.1353/soh.2022.0054.

- Sublette, Ned (October 2015). The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613748237.