Joshua Wong

Joshua Wong | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

黃之鋒 | |||||||||||||

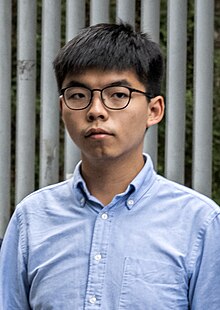

Wong in 2019 | |||||||||||||

| Secretary-General of Demosistō | |||||||||||||

| In office 10 April 2016 – 30 June 2020 | |||||||||||||

| Deputy | Agnes Chow Kwok Hei-yiu Chan Kok-hin | ||||||||||||

| Chairman | Nathan Law Ivan Lam | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Party dissolved | ||||||||||||

| Convenor of Scholarism | |||||||||||||

| In office 29 May 2011 – 20 March 2016 | |||||||||||||

| Deputy | Agnes Chow | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Merge into Demosistō | ||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born | Wong Chi-fung 13 October 1996 British Hong Kong | ||||||||||||

| Political party | Demosistō (2016–2020) | ||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | Scholarism (2012–2016) | ||||||||||||

| Education | Open University of Hong Kong | ||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃之鋒 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄之锋 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Joshua Wong Chi-fung (Chinese: 黃之鋒; Cantonese Yale: Wòhng Jīfūng; born 13 October 1996) is a Hong Kong pro-democracy activist and politician. He served as secretary-general of the pro-democracy party Demosistō until it disbanded following implementation of the Hong Kong national security law on 30 June 2020. Wong was previously convenor and founder of the Hong Kong student activist group Scholarism. Wong first rose to international prominence during the 2014 Hong Kong protests, and his pivotal role in the Umbrella Movement resulted in his inclusion in Time magazine's Most Influential Teens of 2014 and nomination for its 2014 Person of the Year; he was named one of the "world's greatest leaders" by Fortune magazine in 2015, and nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

In August 2017, Wong and two other democracy activists were convicted and jailed for their roles in the occupation of Civic Square at the incipient stage of the 2014 Occupy Central protests; in January 2018, Wong was convicted and jailed again for failing to comply with a court order for clearance of the Mong Kok protest site during the Hong Kong protests in 2014. He also played a major role in persuading U.S. members of Congress to pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act during the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. Wong was disqualified by the Hong Kong government from running in forthcoming District Council elections. In June 2020, he announced he would run for a Legislative Council seat in the upcoming election, and officially applied on 20 July 2020, before his nomination was invalidated on 30 July 2020 along with that of 11 other pro-democracy figures. In December 2020, Wong was convicted and jailed for more than a year over an unauthorised protest outside police headquarters in June 2019. In a national security trial in 2024, a Hong Kong court sentenced Wong to jail for 4 years and 8 months for subversion.

Early life and education

Wong was born in Hong Kong on 13 October 1996,[1] and was diagnosed with dyslexia in early childhood.[2][3] The son of middle-class couple Grace and Roger Wong,[4] Wong was raised as a Protestant Christian in the Lutheran tradition.[5][6] His early interest in social activism was influenced by his father, a retired IT professional,[7] who was a convener of a local anti-gay marriage initiative[8][9][10] and often took him to visit underprivileged communities.[11][12]

Wong studied at the United Christian College (Kowloon East),[13] a private Christian secondary school in Kowloon, and developed organisational and public speaking skills through involvement in church groups.[14] Wong pursued undergraduate studies at the Open University of Hong Kong, having enrolled in a bachelor's degree in political studies and public administration.[15][16] Due to his political activities, Wong took leave from his studies, and reportedly remained a student until 2019.[17]

Student activism (2010–2016)

Early activism

The 2010 anti-high speed rail protests were the first political protests in which Wong took part.[18]

On 29 May 2011, Wong and schoolmate Ivan Lam Long-yin established Scholarism, a student activist group.[19][20][21] The group began with simple means of protest, such as the distribution of leaflets against the newly announced moral and national education (MNE) curriculum.[14][22] In time, however, Wong's group grew in both size and influence, and in 2012 managed to organise a political rally attended by over 100,000 people.[14] Wong received widespread attention as the group's convenor.[23]

Role in 2014 Hong Kong protests

In June 2014, Scholarism drafted a plan to reform Hong Kong's electoral system to push for universal suffrage, under one country, two systems. His group strongly advocated for the inclusion of civic nomination in the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election.[18] Wong as a student leader started a class boycott among Hong Kong's students to send a pro-democracy message to Beijing.[24]

On 27 September 2014, Wong was one of the 78 people arrested by the police during a massive pro-democracy protest,[25] after hundreds of students occupied Civic Square in front of the Central Government Complex as a sign of protest against Beijing's decision on the 2014 Hong Kong electoral reform.[26][24] Unlike fellow protesters, only in response to a court order obtained by writ of habeas corpus was Wong released by police, after 46 hours in custody.[27][28]

During the protests, Wong stated: "Among all the people in Hong Kong, there is only one person who can decide whether the current movement will last and he is [Chief Executive of the region] Leung. If Leung can accept our demands ... (the) movement will naturally come to an end."[29] On 25 September 2014 the state-owned Wen Wei Po published an article which claimed that "US forces" had worked to cultivate Wong as a "political superstar".[30][31] Wong in turn denied every detail in the report through a statement that he subsequently posted online.[31] Wong also said that he was mentioned by name in mainland China's Blue Paper on National Security, which identified internal threats to the stability of Communist Party rule; quoting a line in V for Vendetta, he in turn said that "People should not be afraid of their government, the government should be afraid of their people."[24]

Wong was charged on 27 November 2014 with obstructing a bailiff clearing one of Hong Kong's three protest areas. His lawyer described the charge as politically motivated.[32][33] He was banned from a large part of Mong Kok, one of the protester-occupied sites, as one of the bail conditions.[34] Wong claimed that police beat him and tried to injure his groin as he was arrested, and taunted and swore at him while he was in custody.[35]

After Wong's appearance at Kowloon City Magistrates' Court on 27 November 2014, he was pelted with eggs by two assailants.[36] They were arrested and each fined $3,000 in August 2015, sentences which, on application for review by the prosecution, were subsequently enhanced to two weeks' imprisonment.[37][38]

On 2 December 2014, Wong and two other students began an indefinite hunger strike to demand renewed talks with the Hong Kong government. He decided to end the hunger strike after four days on medical advice.[39]

Aftermath of the Occupy protests

Wong was arrested and held for three hours on Friday, 16 January 2015, for his alleged involvement in offences of calling for, inciting and participating in an unauthorised assembly.[40]

The same month, an article appeared in the Pro-Beijing newspaper Wen Wei Po alleging that Wong had met with the US consul-general in Hong Kong Stephen M. Young during the latter's visit in 2011. It suggested that Wong had links with the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States, which had supposedly offered him military training by the US Army. Wong responded that the claims were pure fiction and "more like jokes."[41]

Wong was denied entry into Malaysia at Penang International Airport, on 26 May 2015, on the basis that he was considered "a threat to Malaysia's ties with China", largely due to his supposed "anti-China" stance in participating in the 2014 Hong Kong protests.[42]

On 28 June 2015, two days before a protest in favour of democracy, Wong and his girlfriend were attacked by an unknown man after watching a film in Mong Kok. The assault sent the two to hospital. Wong sustained injuries to his nose and eyes.[43] No one was arrested.[44][45][46][47]

On 19 August 2015, Wong was formally charged by the Hong Kong Department of Justice with inciting other people to join an unlawful assembly and also joining an unlawful assembly, alongside Alex Chow, the former leader of the Hong Kong Federation of Students.[48][49]

While travelling to Taiwan for a political seminar, "pro-China" protesters attempted to assault Wong at the arrival hall of Taoyuan's Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, necessitating police protection. It was later found that local gangsters were involved.[50][51]

Detention in Thailand

Wong was detained on arrival in Thailand on 5 October 2016. He had been invited to speak about his Umbrella Movement experience at an event marking the 40th anniversary of the Thammasat University massacre, hosted by Chulalongkorn University.[52]

A Thai student activist who invited Wong, Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal, said that Thai authorities had received a request from the Chinese government earlier regarding Wong's visit. His own request to see Wong was denied.[53]

After nearly 12 hours' detention, Wong was deported to Hong Kong.[52] Wong claimed that, upon detention, the authorities would say no more than that he had been blacklisted but, just prior to deportation, they had informed him that his deportation was pursuant to Sections 19, 22 and 54 of the Immigration Act B.E. 2522.[54][55]

Hong Kong Legislator Claudia Mo called the incident "despicable" and stated: "If this becomes a precedent it means it could happen to you or me at any time if somehow Beijing thinks you are a dangerous, unwelcome person".[55] Jason Y. Ng, a Hong Kong journalist and author, stated that Wong's detention showed "how ready Beijing is to flex its diplomatic muscles and [how it] expects neighbouring governments to play ball".[52]

Wong eventually spoke with a Thai audience from Hong Kong via Skype.[56]

Political career (2016–2020)

Founding of Demosistō

In April 2016, Wong founded a new political party, Demosistō, with other Scholarism leaders including Agnes Chow, Oscar Lai, and Umbrella activists, the original student activist group Scholarism having been disbanded. The party advocated for a referendum to be held to determine Hong Kong's sovereignty after 2047, the scheduled expiration of the one country, two systems principle enshrined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Hong Kong Basic Law. As the founding secretary-general of the party, Wong also planned to contest the 2016 Legislative Council election.[57] Wong was still only 19 and being below the statutory minimum age of 21 for candidacy, he filed an application (ultimately unsuccessful) for judicial review of the election law, in October 2015.[58] After his decision to found his own political party, Wong became a focus of criticism, especially on social networks.[59]

Role in 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests

Joshua Wong's release coincided with the ongoing protests against extradition bill.[60] Upon his release, Wong criticised the oppression of protesters by the Hong Kong police, and the extradition draft law as pro-Beijing and called for the Chief Executive of Hong Kong Carrie Lam to resign.[61]

Wong did not take part with the protesters who forcibly broke into the Hong Kong's parliamentary Legislative Council building on 1 July, but he explained the need behind the move. According to him, the reason behind people entering the Legislative Council is that the council is "never democratically elected by people".[62]

Wong was then arrested again on 29 August 2019 the day before a planned demonstration, which was not given city approval.[63]

On 9 September, Wong met with the German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas. The Chinese Foreign Ministry called this move "disrespectful of China's sovereignty and an interference in China's internal affairs".[64]

On 17 September, Wong and other student activists participated in a Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) commission in the United States Capitol. He said that the Chinese government should not grab all the economic benefit from Hong Kong, while attacking the freedom of Hong Kong. He also urged the U.S. Congress to pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang responded that the U.S. should not interfere in China's affairs.[65]

The Speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, met with Wong on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on 18 September. Chinese media sharply criticised Pelosi for this meeting, accusing her of "backing and encouraging radical activists."[66]

In October 2019, Wong met with Thai opposition politician Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit at the Open Future Festival.[67]: 74 Wong tweeted a picture of the two together, writing, "Under the hard-line authoritarian suppression, we stand in solidarity."[67]: 74 The Chinese embassy in Bangkok issued a statement referring to the incident as irresponsible.[67]: 75 Thanathorn issued a statement denying any relationship with Wong and stating that he supports China playing a bigger role both regionally and globally.[67]: 75

2019 District Councillor election controversy

On 29 October 2019, Joshua Wong was barred from running in forthcoming district council elections in the South Horizons West constituency by returning officer Laura Liang Aron, who temporarily took over for Dorothy Ma Chau Pui-fun (South Horizon West's returning officer) after the latter took sick leave. Many (including Joshua Wong himself) have accused the Chinese Central Government and the Hong Kong Government of pressuring Returning Officers into disqualifying Joshua Wong.[68]

National Security Law and the disbanding of Demosistō

On 30 June 2020, Wong, together with Agnes Chow and Nathan Law, announced respectively on Demosistō's Facebook page that they had quit the group in light of the risk of prosecution under the national security law enacted by China.[69][70] Hours later, the Demosistō organisation also announced on its blog that it was ceasing all activity, signing off with the message "We will meet again".[71][72]

2020 legislative election

In June 2020, Wong announced he would run for a Legislative Council seat in the upcoming election,[73] and officially applied on 20 July 2020,[74] before his nomination was invalidated on 30 July 2020 along with that of 11 other pro-democracy figures.[75]

Others

In June 2020 during the George Floyd protests, Wong voiced his support for the Black Lives Matter movement and opposition to police brutality in the United States.[76][77] In the same month, he also called American basketball player Lebron James "hypocritical" for only focusing on issues in the U.S. and staying silent regarding issues in China.[78][79]

Imprisonments

Imprisonment in 2017

Wong, along with two other prominent Hong Kong pro-democracy student leaders Nathan Law and Alex Chow, were jailed for six to eight months on 17 August 2017 for unlawful assembly (Wong and Law) and incitement to assemble unlawfully (Chow) at Civic Square, at the Central Government Complex in the Tamar site, during a protest that triggered the 79-day Occupy sit-ins of 2014. The sentences halted their political careers, as they would be barred from running for public office for five years.[80]

On the third anniversary of the 2014 protests, 28 September 2017, Wong started the first of a series of columns for The Guardian, written from the Pik Uk Correctional Institution, where he said that despite a dull and dry life there, he remained proud of his commitment to the movement.[81]

On 13 October 2017, Wong was convicted with 19 others of contempt of court for obstructing execution of the court's order for clearance of part of the Occupy Central protest zone in Mong Kok in October 2014. The order had been obtained by a public minibus association.[82]

On 14 November 2017, Wong, together with Ivan Lam, commenced an application for judicial review in the High Court challenging the constitutionality of the provision in the Legislative Council Ordinance preventing persons sentenced to terms of imprisonment exceeding three months from standing for office for five years from the date of conviction.[83]

On 18 January 2018, Wong was sentenced by Mr Justice Andrew H C Chan of the High Court to three months' imprisonment in respect of his October 2017 conviction for contempt of court. Nineteen other protesters convicted in respect of the same incident all received prison terms, though the terms were suspended for all but Wong and fellow protester Raphael Wong. As part of his reasoning, Chan expressed the view that, by November 2014, the protests had become pointless and their only effect was to impact the lives of "ordinary citizens" of the region.[84]

Imprisonment in 2019

Wong was sentenced to two months of prison on 16 May 2019, for his involvement in events on 26 November 2014 in Mong Kok, an area in Hong Kong, where demonstrators opposed the police during the Umbrella revolution.[85][86]

Joshua Wong was released on 17 June 2019, after just around a month time in jail because he had already served some time associated to this case back in 2018, thus adding up to a total of two months' term.[87]

Imprisonment beginning in 2020

On 24 September 2020, Wong was arrested when he reported to a police station regarding another case against him. He was charged with "unlawful assembly", which was related to his participation in the 2019 protest against a government ban on face masks, where he was said to have violated the anti-mask law of Hong Kong.[88] On 30 September, he was temporarily released by the court along with activist Koo Sze-yiu. The Principal Magistrate granted the two bail of HK$1,000 each, and imposed a travel ban on Wong at the prosecutors' request.[89]

On 23 November 2020, Wong appeared with Ivan Lam Long-yin and Agnes Chow Ting in the West Kowloon District Court, where they had been expected to stand trial over their roles in the anti extradition bill protest on 21 June 2019.[90] He was charged with organising an unauthorised assembly and of inciting others to take part in the event.[91][92] The three pleaded guilty, and were put in custody until sentencing at a court hearing scheduled for 2 December 2020. Before appearing in court, Wong had said the trio were prepared to face immediate jail terms, and hoped their stance would draw global attention to a criminal justice system he claimed was being "manipulated by Beijing".[93][94][95] Wong, together with Ivan Lam, was remanded to Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre.

On 2 December 2020, Wong was found guilty of organising and inciting unlawful assembly, but not guilty of taking part in it. He was sentenced to 1 year and 1 month in prison. West Kowloon Magistrate Wong Sze-lai, stated: "The defendants called on protesters to besiege the headquarters and chanted slogans that undermine the police force". Amnesty International condemned the sentencing, saying that the Chinese authorities "send a warning to anyone who dares to openly criticise the government that they could be next".[96][97]

It was reported in January 2021 that Wong's family had moved to Australia.[98]

On 29 January 2021, Wong pleaded guilty to two additional charges related to his involvement in a rally on Hong Kong Island on 5 October 2019: taking part in an unauthorised assembly and wearing a facial covering during an unauthorised assembly.[99]

On 13 April 2021, Wong was sentenced to four months in jail for unauthorised assembly and violating an anti-mask law.[100]

On 6 May 2021, the Hong Kong District Court sentenced Wong to ten more months in prison for participating in an unauthorised assembly to mark the 2020 anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. The judge who sentenced him said that "[T]he sentence should deter people from offending and re-offending in the future."[101]

On 17 April 2023, Wong was sentenced to further three months in prison after being convicted of disclosing personal details of a police officer who shot live rounds against a protester in Sai Wan Ho.[102]

The 2023 book Among the Braves by journalists Shibani Mahtani and Timothy McLaughlin states that Wong had requested U.S. political asylum in 2020 but, according to a National Security Council official, his bid was denied despite the risk of Wong being jailed because the State Department under Mike Pompeo had considered national interests in relation to China as having priority.[103][104]

International responses to the 2020 imprisonment

United States

US House of Representative Speaker Nancy Pelosi issued a statement saying "China's brutal sentencing of these young champions of democracy in Hong Kong is appalling."[105] Pelosi further called on the world to denounce "this unjust sentencing and China's widespread assault on Hong Kongers."[106] US Senator Marsha Blackburn also called the sentence destroying "any semblance of autonomy in Hong Kong."[107] In addition, US State Secretary Michael Pompeo decried the prison term in an official statement issued by the State department.[108]

United Kingdom

UK Foreign Minister Dominic Raab issued a statement urging "Hong Kong and Beijing authorities to bring an end to their campaign to stifle opposition" in response to the prison sentences of the three pro-democracy activists.[109]

Japan

Japan's government spokesperson Katsunobu Kato in a regular news conference expressed Japan's "increasingly grave concerns about the recent Hong Kong situation such as sentences against three including Agnes Chow".[110]

Taiwan

The Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC) issued a statement referencing to the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) that "the decision to imprison Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow, and Ivan Lam represents a failure by the Hong Kong government to protect the people's political rights and freedom of speech".[111]

Germany

Maria Adebahr, a Germany's foreign ministry spokesperson, stated that the prison terms are "another building block in a series of worrisome developments that we have seen in connection with human and civil rights in Hong Kong during the last year."[112]

Imprisonment under National Security Law

On 6 January 2021, Wong was among 53 members of the pro-democratic camp who were arrested under the national security law, specifically its provision regarding alleged subversion. The group stood accused of the organisation of and participation in the primaries of July 2020. Wong's home was searched while he was detained.[113] On 28 February 2021, Wong was formally charged, along with 46 others for subversion.[114]

In 2024, following a national security trial in Hong Kong, Wong was sentenced to jail for subversion.[115] The court sentenced Wong to jail for 4 years and 8 months for subversion.[116][117]

Books

- Unfree Speech: The Threat to Global Democracy and Why We Must Act, Now. With Jason Y. Ng. London: Penguin Books, 2020. Introduction by Ai Weiwei, Foreword by Chris Patten.[118]

In the media

Joshua Wong has appeared in several non-fiction films including:

- Lessons in Dissent, 2014

- Umbrella Revolution: History as Mirror Reflection, 2015

- Raise the Umbrellas, 2016

- Joshua: Teenager vs. Superpower, 2017

- Last Exit to Kai Tak, 2018

Awards

- The Times – Young Person of the year, 2014

- AFP – 10 Most influential people, 2014

- YAHOO Top Ten Search Ranking – No.1 (Hong Kong), 2014

- TIME – Person of the Year 2014 (Reader's Poll – 3rd place), 2014[32]

- Foreign Policy – 100 Leading Global Thinkers, 2014

- TIME – The 25 Most Influential Teens of 2014[32]

- TIME Cover (Asia Edition), 2014

- Fortune – World's 50 Greatest Leaders (10th place), 2015[119][120]

- Nobel Peace Prize 2018 nomination, with Nathan Law, Alex Chow and the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, by the United States' Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) (press release)

References

- ^ Sibree, Bron (29 January 2020). "In Unfree Speech, Joshua Wong writes, 'our struggle is your struggle'". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ 《黃之鋒:好學生重新定義》 Archived 30 April 2013 at archive.today, (in Chinese), Ming Pao, 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Joshua Wong, the 17-year-old battling Beijing for greater democracy in Hong Kong". The Straits Times. Asia. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ BBC News. Asia. 2 October 2014. Profile: Hong Kong student protest leader Joshua Wong Archived 26 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Moore, Malcolm. 2014. Portrait of Hong Kong's 17-year-old protest leader Archived 27 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 December 2014.: "He is a strict Christian, and his parents Grace and Roger are Lutherans."

- ^ Sagan, Aleksandra. 2 October 2014. "Joshua Wong: Meet the teen mastermind of Hong Kong's 'umbrella revolution Archived 11 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine". CBC News. Retrieved 10 December 2014.: "They raised him as a Christian – a religion he still identifies with. Wong recalls accompanying his father to visit some of the less fortunate in Hong Kong when he was much younger"

- ^ "Jailed Hong Kong activist Wong back in court on 21st birthday". Hong Kong Free Press. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ "周浩鼎與黃之鋒父站同一陣線" [Holden Chow and Father of Joshua Wong stand side by side]. Oriental Daily News (in Chinese). Hong Kong. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "言論似反同團體" [Speech like anti-gay organization]. Apple Daily (in Chinese). Hong Kong. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Chan, Holmes (2 August 2018). "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong distances self from father in stating support for LGBTQ equality". Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Moyer, Justin. 2014. "The teenage activist wunderkind who was among the first arrested in Hong Kong's Occupy Central Archived 12 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Leah Marieann Klett. 8 October 2014. ""Joshua Wong, Christian Student Leading Hong Kong Protests Will Continue To Fight For Democracy" Archived 9 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Gospel Herald. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Pedroletti, Par. 29, Sept. 2014. Les leaders de la mobilisation citoyenne à Hongkong Archived 3 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Le Monde. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Wong, Joshua (March–April 2015). "Scholarism on the March". New Left Review. 92. London, England. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Joshua Wong, the poster boy for Hong Kong protests". BBC News. BBC. 25 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Lee, Eddie (13 August 2014). "'I was never a top student': Scholarism leader Joshua Wong to study at Open University". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "政情:歷DQ兼坐監 羅冠聰終大學畢業" (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Oriental Press Group Limited. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b Chan, Yannie (15 May 2014). "Joshua Wong". HK Magazine. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Lee, Ada (10 September 2012). "Scholarism's Joshua Wong embodies anti-national education body's energy". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Lai, Alexis (30 July 2012). "'National education' raises furor in Hong Kong". Hong Kong: CNN International. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Hsieh, Steven (8 October 2012). "Hong Kong Students Fight for the Integrity of their Education". The Nation. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ "Scholarism The Alliance Against Moral & National Education" 基本資料 (in Chinese). Scholarism. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Scholarism's Joshua Wong embodies anti-national education body's energy". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Chan, Wilfred; Yuli Yang (25 September 2014). "Echoing Tiananmen, 17-year-old Hong Kong student prepares for democracy battle". CNN International. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Jacobs, Harrison (27 September 2014). "REPORT: Hong Kong's 17-Year-Old 'Extremist' Student Leader Arrested During Massive Democracy Protest". Business Insider. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri (26 September 2014). "Hong Kong police arrest pro-democracy student leader". Financial Times. Hong Kong. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Meet the 17-year-old face of Hong Kong's protests". USA Today. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014.

- ^ Chan, Kelvin (28 September 2014). "Hong Kong police use tear gas on protesters". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Calum MacLeod,"Meet The 17-Year-Old Leading Hong Kong's Protests" Archived 2 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, 2 October 2014

- ^ Branigan, Tania (1 October 2014). "Joshua Wong: the teenager who is the public face of the Hong Kong protests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ a b Steger, Isabella (25 September 2014). "Pro-Beijing Media Accuses Hong Kong Student Leader of U.S. Government Ties". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "Hong Kong Student Leader Joshua Wong Charged With Obstruction". Time. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Hong Kong protesters warned not to return to clash site". BBC. 1 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Joshua Wong banned from Mong Kok areas". RTHK. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (28 November 2014). "Hong Kong student leader considering suing police over arrest, says lawyer". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Lau, Chris; Lai, Ying-kit (27 November 2014). "Joshua Wong pelted with eggs outside court after being banned from Mong Kok". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Chan, Thomas (19 August 2015). "Pair who threw eggs at Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong in anti-Occupy Central protest fined HK$3,000 each". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Joshua Wong egg attackers get two-week jail terms". Hong Kong Economic Journal. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ Agence France Presse (6 December 2014). "Hong Kong student leader Joshua Wong calls off hunger strike". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "Hong Kong Student Leader Joshua Wong Questioned Over Pro-Democracy Protests". Time. 16 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ 29 June 2015. Joshua Wong dismisses Xinhua article on alleged CIA links Archived 21 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine. EJInsight

- ^ Ng, Joyce (26 May 2015). "Occupy student leader Joshua Wong 'a threat to Malaysia's ties with China', police chief admits". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Liu, Juliana. 2 August 2015. Joshua Wong: 'We had no clear goals' in Hong Kong protests Archived 7 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ^ 29 June 2015. Scholarism leader Joshua Wong, girlfriend attacked after movie Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. EJ Insight.

- ^ Lee, Jeremy. 29 June 2015. "Hong Kong student activist Joshua Wong and girlfriend injured after being attacked on street" Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Straits Times.

- ^ Ying-kit, Lai. 29 June 2015. "Attack on Hong Kong student leader Joshua Wong 'a threat to free speech'" Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. South China Morning Post.

- ^ Hong Kong student leader Joshua Wong in chilling assault Archived 9 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Yahoo News, 28 June 2015.

- ^ Master, Farah; Paul Tait (19 August 2015). "Key Hong Kong pro-democracy students charged after Occupy protests". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ 2 September 2015. Leader of Hong Kong democracy protests Joshua Wong to face trial Archived 5 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ^ "Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong under police protection in Taiwan after assault attempt". South China Morning Post. 8 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017.

Taiwan police ramped up protection for Hong Kong student activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung and a few pro-democracy lawmakers after a failed attempt by a pro-China protester to assault him as he arrived in the island state in the early hours [...] About 200 protesters from a pro-China group in Taiwan gathered at the arrival hall of Taipei's Taoyuan International Airport at midnight. They chanted slogans deriding Wong, and Hong Kong legislators Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Edward Yiu Chung-yim – who arrived on the same flight at 12.30am – as "independence scum", saying they were not welcome in Taiwan.

- ^ Coonan, Clifford (10 January 2017). "Hong Kong activist blames pro-Beijing forces after airport assault". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017.

Hong Kong pro-democracy leader Joshua Wong says an assault on him and fellow rights activist Nathan Law at the territory's airport was a co-ordinated attack by pro-Beijing elements angry at his group's calling for more self-determination [...] Mr Wong and Mr Law travelled to Taiwan with fellow lawmakers Edward Yiu and Eddie Chu for talks with Taiwan's pro-independence body, the New Power Party, raising hackles in Beijing. They were greeted by irate pro-China protesters in Taipei as they arrived for the forum.

- ^ a b c Cheung, Eric; Phillips, Tom; Holmes, Oliver (5 October 2016). "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong attacks Thailand after being barred 'at China's request'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Phillips, Tom; Malkin, Bonnie (5 October 2015). "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong detained in Thailand 'at China's request' – reports". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "Thai Immigration blacklists Joshua Wong as requested by China". The Nation. Bangkok, Thailand. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ a b Wong, Joshua (7 October 2016). "I'm a pro-democracy activist. Is that why Thailand chose to deport me?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "Joshua Wong considered 'persona non grata'". The Nation. Bangkok, Thailand. 8 October 2016. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Joshua Wong's party named 'Demosisto'". RTHK. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Wong, Alan (18 February 2016). "Hong Kong Students Who Protested Government Now Seek to Take Part in It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Jason Y. Ng. "Baptism of fire for Joshua Wong and his nascent political party" South China Morning Post. Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 29 de abril de 2016.

- ^ Cheng, Kris (17 June 2019). "Hong Kong democracy leader Joshua Wong released from prison, calls on Chief Exec. Carrie Lam to resign". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Hong Kong : le leader étudiant Joshua Wong réclame la démission de la cheffe de l'exécutif". Les Echos (in French). 1 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Hong Kong protests: Parliament 'never represented its people'". BBC. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "Joshua Wong arrested: Hong Kong pro-democracy activist". BBC. 30 August 2019. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019.

- ^ Hui Min Neo; Poornima Weerasekara (10 September 2019). "China fury as Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong meets German foreign minister". Hong Kong Free Press. AFP News. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Yong, Charissa (18 September 2019). "Hong Kong activists Joshua Wong, Denise Ho take cause to US Congress, urge pressure on Beijing". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "China accuses Pelosi of "interference" as battle rages to control narrative on Hong Kong". CBS News. 20 September 2019. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Han, Enze (2024). The Ripple Effect: China's Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-769659-0.

- ^ "Democracy activist Joshua Wong slams 'politically driven decision' to bar him from running in Hong Kong district council election". South China Morning Post. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Agnes Chow quit Demosisto". The Standard. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Lui, Percy Luen-tim (2024). "The Legislature". In Lam, Wai-man; Lui, Percy Luen-tim; Wong, Wilson (eds.). Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics (3rd ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9789888842872.

- ^ Ho, Kelly; Grundy, Tom (30 June 2020). "Joshua Wong's pro-democracy group Demosisto disbands hours after Hong Kong security law passed". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong security law: Minutes after new law, pro-democracy voices quit". BBC. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Mang, Carol; Chopra, Toby (19 June 2020). "Activist Joshua Wong says he plans to run for Hong Kong legislature". Reuters. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Democracy activist Joshua Wong launches bid for Hong Kong legislature". Reuters. 19 July 2020.

- ^ Ho, Kelly; Grundy, Tom; Creery, Jennifer (30 July 2020). "Hong Kong bans Joshua Wong and 11 other pro-democracy figures from legislative election". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Hillary Leung (12 June 2020). "The world has marched for black lives. Why hasn't Hong Kong?". Coconuts Media. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021.

- ^ Hong Kong's Joshua Wong backs Black Lives Matter, risks wrath of U.S. conservatives Ng Weng Hoong, Georgia Straight, 2 June 2020

- ^ Gaydos, Ryan (12 June 2020). "LeBron James 'hypocritical' for staying silent on Hong Kong's fight while supporting US social justice causes, activist says". Fox News. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022.

- ^ "LeBron James forms group to stop black voter suppression". CBS News, Agence France Presse. 11 June 2020.

- ^ Siu, Jasmine (17 August 2017). "Joshua Wong and other jailed Hong Kong student leaders see political careers halted". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Wong, Joshua (28 September 2017). "Prison is an inevitable part of Hong Kong's exhausting path to democracy". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Cheung, Karen (13 October 2017). "Democracy activists Lester Shum and Joshua Wong among 20 guilty of contempt over Mong Kok Occupy protest". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Cheung, Karen (14 November 2017). "Democracy activists Joshua Wong and Ivan Lam file legal challenge over ban on standing for office". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Cheng, Kris (18 January 2018). "Hong Kong democracy activists Joshua Wong and Raphael Wong jailed over Umbrella Movement site clearance". Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ "Hong Kong's Leader 'Strongly Objects' to Germany Over Activists' Political Asylum". Radio Free Asia. 24 May 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Lau, Chris (16 May 2019). "Occupy poster boy Joshua Wong returns to jail in Hong Kong despite winning appeal for lighter sentence". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Hong Kong’s Joshua Wong to be released from prison on Monday, party says

- ^ "Hong Kong police arrest pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong". DW News. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Wong, Brian (30 September 2020). "Hong Kong court grants activist Joshua Wong temporary release on unauthorised assembly, mask ban charges". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong anti-extradition protesters occupy roads at gov't and police HQ after vowing 'escalation'". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (2 December 2020). "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong jailed for 13 and a half months over protest". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin; May, Tiffany (2 December 2020). "Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow Are Sentenced to Prison Over Hong Kong Protest". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong opposition trio face jail after police HQ siege guilty pleas". South China Morning Post. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "3 Hong Kong Prominent Pro-Democracy Activists in Custody". Voice of America. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin; May, Tiffany (23 November 2020). "Joshua Wong Pleads Guilty Over 2019 Hong Kong Protest". New York Times. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong: Joshua Wong and fellow pro-democracy activists jailed". BBC News. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong, two others jailed over police HQ siege". South China Morning Post. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Family of jailed Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong moves to Australia". Kyodo News.

- ^ "Jailed activist Joshua Wong pleads guilty to charges from 2019 mask rally". South China Morning Post. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong jailed for four months for 2019 protest". Reuters. 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Hong Kong: Joshua Wong sentenced to 10 more months". Deutsche Welle. 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Leung, Kanis (17 April 2023). "Joshua Wong sentenced in another Hong Kong activism case". ABC News. AP. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Lee, Tim (9 November 2023). "Washington 'denied' Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong's asylum bid". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ McLaughlin, Timothy; Mahtani, Shibani (4 November 2023). "The Hong Kong Activist Who Called Washington's Bluff". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Pelosi Statement on Sentencing of Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Leaders". Speaker Nancy Pelosi. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Congress 'seriously concerned' about Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong – Pelosi". Reuters. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong jailed for anti-government protest". NBC News, Reuters. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "On the Political Persecution of Hong Kong Democracy Advocates". United States Department of State. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Possible, We Will Respond as Soon as. "Sentencing of 3 Hong Kong activists: Foreign Secretary's statement". GOV.UK. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Japan voices 'grave concerns' about jailing of Hong Kong activists". Reuters. 3 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Prison sentence against HK activists regrettable: Taiwan government". Taiwan OCAC News. 3 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Key Hong Kong activists jailed over police HQ protest". Associated Press. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "National security law: Hong Kong rounds up 53 pro-democracy activists". BBC. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Hong Kong charges 47 activists in largest use yet of new security law". BBC News. 1 March 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Koh, Ewe (19 November 2024). "Top Hong Kong pro-democracy leaders sentenced to jail". BBC.

- ^ Koh, Ewe (19 November 2024). "Top Hong Kong pro-democracy leaders sentenced to jail". BBC.

- ^ Gan, Chris Lau, Nectar (19 November 2024). "Joshua Wong shouts 'I love Hong Kong' as more than 40 leading democracy leaders handed lengthy prison terms in mass trial". CNN. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huang, Zhifeng, 1996– (18 February 2020). Unfree speech : the threat to global democracy and why we must act, now. Ng, Jason Y.,, Ai, Weiwei. [New York]. ISBN 978-0-14-313571-5. OCLC 1122800632.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Yik Fei, Lam . World's Greatest Leaders: 10: Joshua Wong Archived 27 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Fortune.

- ^ AFP. H.K.'s Joshua Wong among 'world's greatest leaders': Fortune. 27 March 2015. Yahoo! News.

- 1996 births

- Living people

- Hong Kong democracy activists

- Hong Kong Christians

- 2014 Hong Kong protests

- 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests

- Hong Kong Protestants

- Hong Kong people with disabilities

- Progressivism in China

- Chinese free speech activists

- Demosistō politicians

- Youth activists

- Hong Kong children

- Politicians with dyslexia

- Prisoners and detainees of Hong Kong

- Political prisoners held by Hong Kong

- People convicted under the Hong Kong national security law