The Wild One

| The Wild One | |

|---|---|

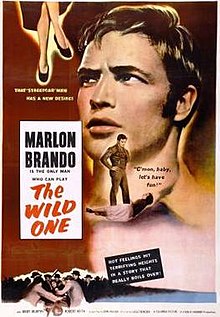

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | László Benedek |

| Screenplay by | John Paxton Ben Maddow |

| Based on | Cyclists' Raid 1951 story in Harper's by Frank Rooney |

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer |

| Starring | Marlon Brando Mary Murphy Robert Keith |

| Narrated by | Marlon Brando |

| Cinematography | Hal Mohr |

| Edited by | Al Clark |

| Music by | Leith Stevens |

Production company | Stanley Kramer Pictures Corp.[1] |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Wild One is a 1953 American crime film directed by László Benedek and produced by Stanley Kramer. The picture is most noted for the character of Johnny Strabler, portrayed by Marlon Brando, whose persona became a cultural icon of the 1950s. The Wild One is considered to be the original outlaw biker film, and the first to examine American outlaw motorcycle gang violence.[2][3][4] The supporting cast features Lee Marvin as Chino, truculent leader of the motorcycle gang "The Beetles".

The film's screenplay was based on Frank Rooney's short story "Cyclists' Raid", published in the January 1951 Harper's Magazine and anthologized in The Best American Short Stories 1952. Rooney's story was inspired by sensationalistic media coverage of an American Motorcyclist Association motorcycle rally that got out of hand on the Fourth of July weekend in 1947 in Hollister, California. The overcrowding, drinking and street stunting were given national attention in the July 21, 1947, issue of Life, with a possibly staged photograph of a wild drunken man on a motorcycle.[5] The events, conflated with the newspaper and magazine reports, Rooney's short story, and the film The Wild One are part of the legend of the Hollister riot.

Plot

[edit]The Black Rebels Motorcycle Club (BRMC), led by Johnny Strabler,[6][7] rides into Carbonville, California, during a motorcycle race and causes trouble. A member of the motorcycle club, Pidgeon, steals the second-place trophy (the first place one being too large to hide) and presents it to Johnny. After an altercation with a steward, a Highway Patrol policeman orders them to leave.

The bikers head to Wrightsville, which has only one elderly, conciliatory lawman, Chief Harry Bleeker, to maintain order. The residents are uneasy, but mostly willing to put up with their visitors. When their antics cause Art Kleiner to swerve and crash his car, he demands that something be done, but Harry is reluctant to act, a weakness that is not lost on the interlopers. This accident results in the gang having to stay longer in town, as one member called Crazy injured himself falling off his motorcycle. Although the young men become more and more boisterous, their custom is enthusiastically welcomed by Harry's brother Frank who runs the local cafe-bar, employing Harry's daughter, Kathie, and the elderly Jimmy.

Johnny meets Kathie and asks her out to a dance being held that night. Kathie politely turns him down, but Johnny's dark, brooding personality visibly intrigues her. When Mildred, another local girl, asks him, "What are you rebelling against, Johnny?", he answers "Whaddaya got?" Johnny is attracted to Kathie and decides to stay a while. However, when he learns that she is the policeman's daughter, he changes his mind. A rival biker club arrives. Their leader Chino bears a grudge against Johnny. Chino reveals the two groups used to be one large club before Johnny split it up. When Chino takes Johnny's trophy, the two start fighting and Johnny wins.

Meanwhile, local Charlie Thomas stubbornly tries to drive through; he hits a parked motorcycle and injures Meatball, one of Chino's bikers. Chino pulls Charlie out and leads both gangs to overturn his car. Harry starts arresting Chino and Charlie, but when other townspeople remind Harry that Charlie would cause problems for him in the future, he only takes Chino to the station. Later that night some members of the rival biker club harass Dorothy, the telephone switchboard operator into leaving, thereby disrupting the townspeople's communication, while the BRMC abducts Charlie and puts him in the same jail cell as Chino, who is too drunk to leave with the club.

Later, as both clubs wreck the town and intimidate the residents, some bikers led by Gringo chase and surround Kathie, but Johnny rescues her and takes her on a long ride in the countryside. Frightened at first, Kathie comes to see that Johnny is genuinely attracted to her and means her no harm. When she opens up to him and asks to go with him, he rejects her. Crying, she runs away. Johnny drives off to search for her. Art sees and misinterprets this as an attack. The townspeople have had enough. Johnny's supposed assault on Kathie is the last straw. Vigilantes led by Charlie chase and catch Johnny and beat him mercilessly, but he escapes on his motorcycle when Harry confronts the mob. The mob give chase. Johnny is hit by a thrown tire iron and falls. His riderless motorcycle strikes and kills Jimmy.

Sheriff Stew Singer arrives with his deputies and restores order. Johnny is initially arrested for Jimmy's death, with Kathie pleading on his behalf. Seeing this, Art and Frank state that Johnny was not responsible for the tragedy, with Johnny being unable to thank them. The motorcyclists are ordered to leave the county, albeit paying for all damage. However, Johnny returns alone to Wrightsville and revisits the cafe to say goodbye to Kathie one final time. He first tries to hide his humiliation and acts as though he is leaving after getting a cup of coffee, but then he returns, smiles and gives her the stolen trophy as a gift.

Cast

[edit]- Marlon Brando as Johnny Strabler

- Mary Murphy as Kathie Bleeker

- Robert Keith as Harry Bleeker

- Lee Marvin as Chino

- Jay C. Flippen as Sheriff Singer

- Peggy Maley as Mildred

- Hugh Sanders as Charlie Thomas

- Ray Teal as Frank Bleeker

- John Brown as Bill Hannegan

- Will Wright as Art Kleiner

- Robert Osterloh as Ben

- William Vedder as Jimmy

- Yvonne Doughty as Britches

Uncredited

- Wally Albright as Cyclist

- Timothy Carey as Chino Boy

- John Doucette as Official

- Robert Bice as Wilson

- Harry Landers as GoGo

- Eve March as Dorothy

- Alvy Moore as Pidgeon

- Pat O'Malley as Sawyer

- Jerry Paris as Dextro

- Angela Stevens as Betty

- Gil Stratton as Mouse

- Gene Peterson as Crazy

- Robert Anderson as Policeman

- John Tarangelo as Red

- Danny Welton as Bee Bop

- Darren Dublin as Dinky

- Chris Alcaide as Deputy

- Don Anderson as Stinger

- Keith Clarke as Gringo

Production

[edit]The main differences between the screenplay and Frank Rooney's source story, "Cyclists' Raid", were that there were no rival gangs nor any romance between Kathie and any of the motorcyclists, and indeed she is the victim of the fatal motorcycle accident. Unlike in the film, it is her father (who is not a policeman) who exacts violent revenge upon an innocent young motorcyclist.

Brando later revealed in his autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me (1994 Random House), that "(m)ore than most parts I've played in the movies or onstage, I related to Johnny, and because of this, I believe I played him as more sensitive and sympathetic than the script envisioned. There's a line where he snarls, 'Nobody tells me what to do'. That's exactly how I've felt all my life." Brando also stipulated in his contract that he would ride his own Triumph motorcycle in the film.

The technical advisor on the film was identified in the April 1953 issue of Motorcyclist as Carey Loftin, which also noted that 150 motorcyclists were hired as extras.

Filming mainly took place at the Columbia Pictures Ranch, "Western Street 'A'", which was re-dressed to depict a 1950s Midwest American town with the dirt paths covered in asphalt.

The sharpness of the film photography was achieved with a Garutso lens, according to Halliwell's Filmgoers Companion.

Release

[edit]Home media

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

The Wild One was released on VHS and Betamax formats and later on DVD. In the United States, a DVD was released in November 1998 by Sony Pictures.[8] In 2013, Sony Pictures released it on Blu-ray in Germany with special features, including an introduction by Karen Kramer (Stanley Kramer's wife) and three featurettes titled "Hollister, California: Bikers, Booze and the Big Picture", "Brando: An Icon is Born" and "Stanley Kramer: A Man's Search for Truth".[9] A U.S. and Canadian Blu-ray was released in 2015 by Mill Creek Entertainment with no extra features.[10] The film was released in the United Kingdom on May 22, 2017 by Powerhouse Films with a few of the previous extras ported over. The features include an audio commentary with film historian Jeanine Basinger, a 25-minute featurette titled "The Wild One and the BBFC", "The Wild One on Super 8", an image gallery, and theatrical trailer.[11]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]

The Wild One was generally well received by film critics. Rotten Tomatoes reports that 76% critics have given the film a positive response based on 25 reviews, with a rating average of 7/10.[12] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader wrote, "Legions of Brando impersonators have turned his performance in this seminal 1954 motorcycle movie into self-parody, but it's still a sleazy good time."[13] Variety noted that the film "is long on suspense, brutality and sadism ... All performances are highly competent."[14]

Leslie Halliwell stated in his Halliwell's Filmgoers Companion that the film was a "(b)rooding, compulsive, well-made little melodrama" whose narrative however does "lack dramatic point".

Controversies

[edit]In the United Kingdom, the film was refused a certificate for public exhibition by the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC), effectively banning the film for 14 years. There were some screenings in film societies where local councils overturned the BBFC's decision.[15][16] In his book Censored (Chatto & Windus 1994), Tom Dewe Matthews reports that then-chairman of the BBFC, Arthur Watkins, rejected one of the many requests by Columbia Pictures for certification of the film, stating:

Our objection is to the unrestricted hooliganism. Without the hooliganism there can be no film and with it there can be no certificate.

Other members of the board such as his successor as chairman, John Trevelyan, backed him, stating, reports Matthews, that:

Having regard to the widespread concern about the increase in juvenile crime, the Board is not prepared to pass any film dealing with this subject unless the compensating moral values are so firmly presented as to justify its exhibition to audiences likely to contain (even with an "X" certificate) a large number of young and immature persons.

Columbia Pictures, Matthews wrote, even offered a new version of the film with a preface and a new ending but that too was rejected upon viewing by the BBFC.

Matthews states that Trevelyan maintained his predecessor's stance, albeit in more conciliatory terms, when he assumed the chairmanship of BBFC, telling Columbia in a letter to them dated 3 April 1959:

There has been a lot of publicity about adolescent gangs in London and elsewhere recently and, while in some ways the present gangs are more vicious than those depicted in the film, the behaviour of Brando and the two gangs to authority and adults generally is of the kind that provides a dangerous example to those wretched young people who take every opportunity of throwing their weight about [...] Once again we have made this decision [to refuse certification] with reluctance because we think it is a splendid picture. I do hope that the time will come, and come soon, when we do not have to worry about this kind of thing, but I am afraid that we do have to worry about it now.

Matthews states that the film was rejected twice again, the second time after the scooter-riding mods and motorcycle-riding rockers rioted at Clacton in March 1964.

It was only with someone not concerned with the original refusal – Lord Harlech – assuming the chairmanship that The Wild One was finally passed for general exhibition as, Matthews reports, "the film would no longer be likely to have its original impact".

On November 21, 1967, the film was passed for exhibition by the BBFC and received an 'X' certificate.[17][18] The premiere was, Matthews writes, at the Columbia Cinema, Shaftsbury Avenue in February 1968.

As recounted in his book Seats in All Parts: Half a Lifetime at the Movies, film critic Leslie Halliwell had, in 1954, been the first to show the film in the United Kingdom at his Rex cinema in Cambridge, having successfully petitioned his local authority to grant a certificate despite the BBFC's recent refusal to do so. Despite attendances from motorcycle clubs, Teddy Boys and "a sprinkling of London sophisticates and actors", he noted his usual clientele were largely unimpressed and the film "played to very average business".

In an article for Sight & Sound (summer 1955 issue, vol. 25, no. 1), Halliwell opined the BBFC ban gave a wrong impression of the film and, had it been awarded an 'A' certificate, would have attracted limited audiences of those who appreciated Kramer's work with no sensation. Looking back at his decision, Trevelyan himself in his book What the Censor Saw (Michael Joseph Ltd 1973), sought to justify and clarify his decision that he:

must refuse a certificate, not really on the grounds of its violence, as it is usually stated but because of its message. The film showed a gang of motor-cycle thugs terrorising a small town; it was in fact based on a real incident. It showed authority became scared, and therefore weak, and suggested that if there were enough hoodlums and they behaved in a menacing way they could get away with it. This was at a time when the activities of what were called the 'Teddy Boys' were beginning to cause concern. We felt that there was a danger of stimulation and imitation. On two or three occasions in the following years we were asked by the distributor to reconsider this decision, but we kept to it until 1969 [sic] when we gave it an 'X' certificate; even then there was some criticism of our decision.

There were objections to the film in the United States of America, too, but of a more commercial nature. According to the book Triumph Motorcycles in America, Triumph's then-US importers, Johnson Motors, objected to the prominent use of Triumph motorcycles in the film. The full text of the letter sent by Triumph's American importers to the President of the Motion Picture Association of America Inc was published in the April 1953 issue of Motorcyclist magazine in the article "A Report on Stanley Kramer's Motion Picture of The Wild One". Therein, Triumph's US importers stated that the film:

is calculated to do nothing but harm particularly to a minority group of business people- motorcycle dealers throughout the U.S.A.

Moreover, the letter went on to claim:

To say that the story is unfair is putting it mildly. and you cannot deny that the general impression will be left with those who see the film that a motorcyclist is a drunken, irresponsible individual "just not nice to know". [...] I urge you give the foregoing comments your unbiased consideration, with a view of stopping the production of this film.

Having visited the set, the Motorcyclist journalist further stated:

Maybe I was at the studio on the wrong day, but from my observations I don't see where motorcycling will benefit from Kramer's "celluloid saga of cycling". [...] I don't see where the motorcycle industry, including manufacturers, distributors, dealers and riders will benefit from The Wild One.

However, in the following decade, Gil Stratton Jr, who played Mouse in the film, advertised Triumph motorcycles in his later career as a famous TV sports announcer. As of 2014[update], the manufacturers publicly were publicly identifying Brando as a celebrity who had helped to "cement the Triumph legend".[19]

In the March 2, 1953, issue of Time magazine at page 38, Marlon Brando acknowledged the controversy surrounding the production, saying he would retire from films because:

The stage has more freedom from censorship than the screen, e.g., The Wild One, about a band of rough riding motorcyclists. There were 15 different pressure groups that didn't want this picture to be made [...]

Reflecting forty years later in his autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me (1994, Random House), Brando said he had "had fun" making the film, but that "none of us involved in the picture ever imagined that it would instigate or encourage youthful rebellion".

He noted that "[i]n this film we were accused of glamorizing motorcycle gangs, whose members were considered inherently evil, with no redeeming qualities" and "[a] few nuts even claimed that The Wild One was part of a Hollywood campaign to loosen our morals and incite young people to rebel against their elders."

Brando also revealed that he could not watch the film for weeks because he thought it too violent. While he suspected that producer Stanley Kramer, writer John Paxton and director Lazlo Benedek may have initially intended to illustrate how easy it was for men to descend into an amoral pack mentality, in the end "they were really only interested in telling an entertaining story".

In popular culture

[edit]

The persona of Johnny as portrayed by Brando became an influential image in the 1950s. His character wears long sideburns, a Perfecto-style motorcycle jacket and a tilted cap; he rides a 1950 Triumph Thunderbird 6T. His haircut helped to inspire a craze for sideburns, followed by James Dean and Elvis Presley, among others.[citation needed]

Presley also used Johnny's image as a model for his role in Jailhouse Rock.[20]

James Dean bought a Triumph TR5 Trophy motorcycle to mimic Brando's own Triumph Thunderbird 6T motorcycle that he rode in the film.[21]

In his autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, Brando, writing of the film's effect, revealed that he himself was "as surprised as anyone when T-shirts, jeans and leather jackets suddenly became symbols of rebellion".

A 1964 silkscreen ink on canvas painting titled "Four Marlons" by Andy Warhol depicted four identical portraits of the actor as Johnny leaning across his Triumph Thunderbird motorcycle. The same portrait but singular was exhibited as "Marlon Brando" in 1967.

Mad magazine parodied The Wild One in their September 1954 issue as The Wild 1/2 starring "Marlon Branflakes".

One story maintains that the Beatles took their name from the rival motorcycle club, referred to as The Beetles,[22] as referenced in The Beatles Anthology (but as aforementioned, the film was banned in Britain until 1967).[23]

The punk band the Ramones was inspired to adopt leather jackets by the film. Coincidentally, the guitarist's first name was Johnny, much like Brando's character.[24]

The name of American band Black Rebel Motorcycle Club was inspired by the film.[25][26]

The exchange between Mildred and Johnny is repeated in The Simpsons episode "Separate Vocations" (Lisa Simpson responding to Principal Skinner),[27] and in Everybody Loves Raymond in the second part of the two Italy episodes (Frank responding to Raymond). In the film The Bikeriders, the same exchange when seen on a television screening of The Wild One inspires the character ‘Johnny’ (Tom Hardy) to start his motorcycle club.[28]

In Twin Peaks, Michael Cera plays Wally Brando, who dresses like Johnny Strabler and does a Marlon Brando impression.[29]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Wild One – AFI | Catalog – American Film Institute

- ^ Pratt, Alan R. (2006), "6 Motorcycling, Nihilism, and the Price of Cool", in Rollin, Bernard E.; Gray, Carolyn M.; Mommer, Kerri; et al. (eds.), Harley-Davidson and Philosophy: Full-Throttle Aristotle, Open Court, p. 25

- ^ Veno, Arthur; Gannon, Ed (2002), The Brotherhoods: Inside the Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs, Allen & Unwin, pp. 25–26, ISBN 9781865086989

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (2008), A Short History of Film, Rutgers University Press, p. 190, ISBN 9780813544755

- ^ "Cyclist's Holiday; He and his friends terrorize a town", Life, Time Inc, p. 31, July 21, 1947, ISSN 0024-3019, retrieved January 22, 2015

- ^ Tim Dirks, "Filmsite movie review: The Wild One", AMC Filmsite, retrieved January 22, 2015,

It was the first feature film to examine outlaw motorcycle gang violence in America.

- ^ Christopher Gair (2007). The American Counterculture. Edinburgh University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7486-1989-4.

- ^ "The Wild One DVD United States Sony Pictures". Blu-ray.com. November 10, 1998. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wild One Blu-ray Germany Der Wilde Sony Pictures". Blu-ray.com. June 13, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wild One Blu-ray United States Mill Creek Entertainment". Blu-ray.com. March 17, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wild One Blu-ray United Kingdom Powerhouse Films". Blu-ray.com. May 22, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wild One". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "The Wild One". Chicago Reader.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1952). "Review: 'The Wild One'". Variety.

- ^ "THE WILD ONE (N/A)". British Board of Film Classification. January 18, 1954. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Case Studies: The Wild One (N/A)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "The Wild One (X)". British Board of Film Classification. November 21, 1967. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Shary, Timothy; Seibel, Alexandra (2007). Youth culture in global cinema. University of Texas Press. p. 17.

- ^ Triumph Heritage at Triumph Motorcycles official website. Accessed 18 October 2014

- ^ Burton I. Kaufman & Diane Kaufman (2009), The A to Z of the Eisenhower Era, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-7150-5, p. 38.

- ^ Dr. Martin H. Levinson (2011), Brooklyn Boomer: Growing Up in the Fifties, iUniverse, ISBN 1-4620-1712-6, p. 81.

- ^ "The wild one" screenplay, p. 13

- ^ Persails, Dave (1996). "The Beatles: What's In A Name ?". Abbeyrd. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Trotman, Samuel (January 26, 2020). "The Surprising Homoerotic Roots of The Ramone's Style". Denim Dudes. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Dye, David (August 9, 2007). "Black Rebel Motorcycle Club: Gutsy Rock 'n' Roll". NPR.

- ^ Eric James Abbey (2006),Garage Rock and Its Roots: Musical Rebels and the Drive for Individuality, McFarland, ISBN 0786451254, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia, eds. The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family. Created by Matt Groening; edited by Ray Richmond and Antonia Coffman. (1st ed.). New York: HarperPerennial. LCCN 98-141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M. ISBN 978-0-06-095252-5. p. 83.

- ^ Loughrey, Clarisse (June 20, 2024). "The Bikeriders review: Tom Hardy and Austin Butler lead a tough, tender American tragedy". The Independent.

- ^ Nguyen, Hanh (May 30, 2017). "'Twin Peaks' MVP Wally Brando: 5 Reasons Michael Cera's Brilliant Cameo Is Just What the Show Needed". IndieWire. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1953 films

- 1950s teen drama films

- American auto racing films

- American gang films

- American teen drama films

- American black-and-white films

- Motorcycle racing films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Films based on American short stories

- Films directed by László Benedek

- Films originally rejected by the British Board of Film Classification

- Films produced by Stanley Kramer

- Films scored by Leith Stevens

- Films set in California

- Outlaw biker films

- 1953 drama films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- Counterculture of the 1950s