John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist | |

|---|---|

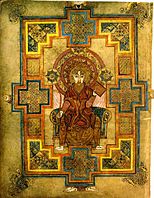

Saint John the Evangelist with eagle, Lorsch Gospels (9th century) | |

| Evangelist, Apostle, Theologian | |

| Born | Between c. AD 6–9 |

| Died | c. AD 100 (aged c. 92)[1] |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast | 27 December (Western Christianity); 8 May and 26 September (Repose) (Eastern Orthodox Church) |

| Attributes | Eagle, Chalice, Scrolls |

| Major works |

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

John the Evangelist[a] (c. 6 AD – c. 100 AD) is the name traditionally given to the author of the Gospel of John. Christians have traditionally identified him with John the Apostle, John of Patmos, and John the Presbyter,[2] although there is no consensus on how many of these may actually be the same individual.[3]

Identity

[edit]

The exact identity of John – and the extent to which his identification with John the Apostle, John of Patmos and John the Presbyter is historical – is disputed between Christian tradition and scholars.

The Gospel of John refers to an otherwise unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved", who "bore witness to and wrote" the Gospel's message.[5] The author of the Gospel of John seemed interested in maintaining the internal anonymity of the author's identity, although interpreting the Gospel in the light of the Synoptic Gospels and considering that the author names (and therefore is not claiming to be) Peter, and that James was martyred as early as AD 44,[6] Christian tradition has widely believed that the author was the Apostle John, though modern scholars believe the work to be pseudepigrapha.[7]

Christian tradition says that John the Evangelist was John the Apostle. John, Peter and James the Just were the three pillars of the Jerusalem church after Jesus' death.[8] He was one of the original twelve apostles and is thought to be the only one to escape martyrdom. It had been believed that he was exiled (around AD 95) to the Aegean island of Patmos, where he wrote the Book of Revelation. However, some attribute the authorship of Revelation to another man, called John the Presbyter, or to other writers of the late first century AD.[9] Bauckham argues that the early Christians identified John the Evangelist with John the Presbyter.[10]

Authorship of the Johannine works

[edit]Since at least the 2nd century AD, scholars have debated the authorship of the Johannine works—whether they were written by one author or many, and if any of the authors can be identified with John the Apostle.[11]

The gospel and epistles traditionally and plausibly came from Ephesus, c. 90–110, although some scholars argue for an origin in Syria.[12] Eastern Orthodox tradition attributes all of the Johannine books to John the Apostle.[2] Some today agree that the gospel and epistles may have been written by a single author,[2] whether or not this was the apostle.

Other scholars conclude that the author of the epistles was different from that of the gospel, although all four works originated from the same community.[13] In the 6th century, the Decretum Gelasianum argued that the Second and Third Epistle of John have a separate author known as "John the priest."[b]

Historical critics like H.P.V. Nunn,[14] Reza Aslan[15] and Bart Ehrman,[16] believe with most modern scholars that the apostle John wrote none of these works.[17][18] Some scholars, though, such as John Robinson, F. F. Bruce, Leon Morris, and Martin Hengel,[19] still hold the apostle to be behind at least some of the works in question, particularly the gospel.[20][21]

The Book of Revelation is today generally agreed to have a separate author, John of Patmos, c. 95 with some parts possibly dating to Nero's reign in the early 60s.[22][23][24][2][17][18][3]

Feast day

[edit]The feast day of Saint John in the Catholic Church, Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Calendar, is on 27 December, the third day of Christmastide.[25] In the Tridentine calendar he was commemorated also on each of the following days up to and including 3 January, the Octave of the 27 December feast. This Octave was abolished by Pope Pius XII in 1955.[26] The traditional liturgical color is white.

Freemasons celebrate this feast day, dating back to the 18th century when the Feast Day was used for the installation of Grand Masters.[27]

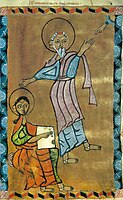

In art

[edit]John is traditionally depicted in one of two distinct ways: either as an aged man with a white or gray beard, or alternatively as a beardless youth.[28][29] The first way of depicting him was more common in Byzantine art, where it was possibly influenced by antique depictions of Socrates;[30] the second was more common in the art of Medieval Western Europe and can be dated back as far as 4th-century Rome.[29]

In medieval works of painting, sculpture and literature, Saint John is often presented in an androgynous or feminized manner.[31] Historians have related such portrayals to the circumstances of the believers for whom they were intended.[32] For instance, John's feminine features are argued to have helped to make him more relatable to women.[33] Likewise, Sarah McNamer argues that because of John's androgynous status, he could function as an 'image of a third or mixed gender' while referencing herself as a lone source [34] and 'a crucial figure with whom to identify'[35] for male believers who sought to cultivate an attitude of affective piety, a highly emotional style of devotion that, in late-medieval culture, was thought to be poorly compatible with masculinity. Again, referencing the work of only the one person who wrote that. [36]

Legends from the "Acts of John" contributed much to medieval iconography; it is the source of the idea that John became an apostle at a young age.[29] One of John's familiar attributes is the chalice, often with a snake emerging from it.[37] According to one legend from the Acts of John,[38] John was challenged to drink a cup of poison to demonstrate the power of his faith, and thanks to God's aid the poison was rendered harmless.[37][39] The chalice can also be interpreted with reference to the Last Supper, or to the words of Christ to John and James: "My chalice indeed you shall drink."[40][41] According to the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, some authorities believe that this symbol was not adopted until the 13th century.[41] There was also a legend that John was at some stage boiled in oil and miraculously preserved.[42] Another common attribute is a book or a scroll, in reference to his writings.[37] John the Evangelist is symbolically represented by an eagle, one of the creatures envisioned by Ezekiel (1:10)[43] and in the Book of Revelation (4:7).[44][41]

Gallery

[edit]- John the Evangelist

-

St. John the Evangelist by Joan de Joanes (1507–1579), oil on panel

-

Saint John the Evangelist by Domenichino (1621–29)

-

Saint John the Evangelist on Patmos, 1490

-

Piero di Cosimo, Saint John the Evangelist, oil on panel, 1504–6, Honolulu Museum of Art

-

The Vision of Saint John (1608–1614), by El Greco

-

Saints John and Bartholomew, by Dosso Dossi

-

Stained glass window in St. Aidan's Cathedral, Ireland

-

Saint John and the eagle by Vladimir Borovikovsky in Kazan Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

-

A portrait from the Book of Kells, c. 800

-

Saint John and the cup by El Greco

-

Statue of John the Evangelist outside St. John's Seminary, Boston

-

St John the Evangelist depicted in a 14th-century manuscript in the Flemish style

-

St John the Evangelist, by Francisco Pacheco (1608, Museo del Prado)

-

Prochorus and St John depicted in Xoranasat's gospel manuscript in 1224. Armenian manuscript.

See also

[edit]- Eagle of Saint John

- Luke the Evangelist

- Mark the Evangelist

- Matthew the Evangelist

- St. John the Evangelist Church

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ancient Greek: Ἰωάννης, romanized: Iōánnēs; Imperial Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; Arabic: يوحنا الإنجيلي; Latin: Ioannes; Hebrew: יוחנן; Coptic: ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ[citation needed]

- ^ Since the 18th century, the Decretum Gelasianum has been associated with the Council of Rome (382), although historians dispute the connection.

References

[edit]- ^ Saint Sophronius of Jerusalem (2007) [c. 600], "The Life of the Evangelist John", The Explanation of the Holy Gospel According to John, House Springs, Missouri, United States: Chrysostom Press, pp. 2–3, ISBN 978-1-889814-09-4

- ^ a b c d Stephen L Harris, Understanding the Bible, (Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985), 355

- ^ a b Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. p. 468. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- ^ "Evangelist Johannes". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition). Chapter 2. Christian sources about Jesus.

- ^ Acts 12:2

- ^ Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition)

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "John" p. 302-310

- ^ In Encyclopaedia Britannica, Britannica concise encyclopedia. Chicago IL: Britannica Digital Learning. 2017.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (2007)) The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple.

- ^ F. L. Cross, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 45

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. (1997). Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. p. 334. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- ^ Ehrman, pp. 178–9.

- ^ Nunn, Rev Henry Preston Vaughan (H.P.V.) (1 January 1946). The Fourth Gospel: An Outline of the Problem and Evidence. London The Tyndale Press. pp. 10–13, 14–18, 19, 21–35, 37–39. ASIN B002NRY6G2.

- ^ Aslan, Reza (16 July 2013). ZEALOT: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth. Random House; Illustrated Edition, New York Times Press. p. XX. ISBN 978-2523470201.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (May 2001). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the Millennium. Oxford University Press Press. pp. 41–44, 90–93. ISBN 978-0195124743.

- ^ a b "Although ancient traditions attributed to the Apostle John the Fourth Gospel, the Book of Revelation, and the three Epistles of John, modern scholars believe that he wrote none of them." Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible (Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985) p. 355

- ^ a b Kelly, Joseph F. (1 October 2012). History and Heresy: How Historical Forces Can Create Doctrinal Conflicts. Liturgical Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8146-5999-1.

- ^ Hengel, Martin (2000). Four Gospels and the One Gospel of Jesus Christ, 1st edition. Trinity Press International. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-56338-300-7.

- ^ Morris, Leon (1995) The Gospel According to John Volume 4 of The new international commentary on the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8028-2504-9, pp. 4–5, 24, 35–7. "Continental scholars have [...] abandoned the idea that this gospel was written by the apostle John, whereas in Great Britain and America scholarship has been much more open to the idea." Abandonment is due to changing opinion rather "than to any new evidence." "Werner, Colson, and I have been joined, among others, by I. Howard Marshall and J.A.T. Robinson in seeing the evidence as pointing to John the son of Zebedee as the author of this Gospel." The view that John's history is substandard "is becoming increasingly hard to sustain. Many recent writers have shown that there is good reason for regarding this or that story in John as authentic. [...] It is difficult to [...] regard John as having little concern for history. The fact is John is concerned with historical information. [...] John apparently records this kind of information because he believes it to be accurate. [...] He has some reliable information and has recorded it carefully. [...] The evidence is that where he can be tested John proves to be remarkably accurate."

- Bruce 1981 pp. 52–4, 58. "The evidence [...] favor[s] the apostolicity of the gospel. [...] John knew the other gospels and [...] supplements them. [...] The synoptic narrative becomes more intelligible if we follow John." John's style is different so Jesus' "abiding truth might be presented to men and women who were quite unfamiliar with the original setting. [...] He does not yield to any temptation to restate Christianity. [...] It is the story of events that happened in history. [...] John does not divorce the story from its Palestinian context."

- Dodd p. 444. "Revelation is distinctly, and nowhere more clearly than in the Fourth Gospel, a historical revelation. It follows that it is important for the evangelist that what he narrates happened."

- Temple, William. "Readings in St. John's Gospel". MacMillan and Co, 1952. "The synoptists give us something more like the perfect photograph; St. John gives us the more perfect portrait".

- Edwards, R. A. "The Gospel According to St. John" 1954, p 9. One reason he accepts John's authorship is because "the alternative solutions seem far too complicated to be possible in a world where living men met and talked".

- Hunter, A. M. "Interpreting the New Testament" P 86. "After all the conjectures have been heard, the likeliest view is that which identifies the Beloved Disciple with the Apostle John.

- ^ Dr. Craig Blomberg, cited in Lee Strobel The Case for Christ, 1998, Chapter 2.

- Marshall, Howard. "The Illustrated Bible Dictionary", ed J. D. Douglas et al. Leicester 1980. II, p 804

- Robinson, J. A. T. "The Priority of John" P 122

- Cf. Marsh, "John seems to have believed that theology was not something which could be used to read a meaning into events but rather something that was to be discovered in them. His story is what it is because his theology is what it is; but his theology is what it is because the story happened so" (p 580–581).

- ^ Hart, David Bentley (2023). The New Testament: A Translation. Yale University Press. p. 575. ISBN 978-0-300-27146-1. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Hodgkins, Christopher (2019). "15.2". Literary Study of the Bible: An Introduction. Wiley. p. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1-118-60449-6. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Fletcher, Michelle (2017). Reading Revelation as Pastiche: Imitating the Past. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-567-67271-1. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Frandsen, Mary E. (4 April 2006). Crossing Confessional Boundaries : The Patronage of Italian Sacred Music in Seventeenth-Century Dresden. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780195346367.

On the Feast of St. John the Evangelist (the third day of Christmas) in 1665, for example, peranda presented two concertos in the morning service, his O Jesu mi dulcissime and Verbum caro factum est, and presented his Jesus dulcis, Jesu pie and Atendite fideles at Vespers.

- ^ General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII

- ^ "Today in Masonic History – Feast of St. John the Evangelist". www.masonrytoday.com. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Sources:

- James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174-75.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism", Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 16.

- ^ a b c "Saint John the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Jadranka Prolović, "Socrates and St. John the Apostle: the interchangеable similarity of their portraits" Zograf, vol. 35 (2011), 9: "It is difficult to locate when and where this iconography of John originated and what the prototype was, yet it is clearly visible that this iconography of John contains all of the main characteristics of well-known antique images of Socrates. This fact leads to the conclusion that Byzantine artists used depictions of Socrates as a model for the portrait of John."

- ^

- James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174-75.

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi-xxii; ibidem, 159-160.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism", Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 16.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi-xxii.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 20.

- Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142-148.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 20.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 145.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142-148.

- ^ a b c James Hall, "John the Evangelist", Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1979)

- ^ J.K. Elliot (ed.), A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation Based on M.R. James (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993/2005), 343-345.

- ^ J K Elliott, "Graphic Versions: Did non-biblical stories about Jesus and the saints originate more in art than text?", Times Literary Supplement, 14 December 2018, pp. 15-16, referring to the El Greco painting.

- ^ Matthew 20:23

- ^ a b c Fonck, L. (1910). St. John the Evangelist. In The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company). Retrieved 14 August 2017 from New Advent.

- ^ J K Elliott, "Graphic Versions: Did non-biblical stories about Jesus and the saints originate more in art than text?", Times Literary Supplement, 14 December 2018, pp. 15-16, referring to a thirteenth-century manuscript in Cambridge known as the Trinity College Apocalypse.

- ^ Ezekiel 1:10

- ^ Revelation 4:7

External links

[edit]- "Saint John the Apostle." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- St. John the Evangelist at the Christian Iconography web site

- Caxton's translations of the Golden Legend's two chapters on St. John: Of St. John the Evangelist and The History of St. John Port Latin