John Wilkes Booth: Difference between revisions

Techman224 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 69.74.223.2 to last revision by ClueBot (HG) |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==Background and early life== |

==Background and early life== |

||

Booth's parents, the noted British [[Shakespeare in performance|Shakespearean]] actor [[Junius Brutus Booth]] and his mistress Mary |

Booth's parents, the noted British [[Shakespeare in performance|Shakespearean]] actor [[Junius Brutus Booth]] and his mistress Mary 'dlskajfklasujiewrjk jasdklfjal;fjk Holmes, came to the United States from England in June 1821.<ref>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Gene|title=American Gothic: the story of America’s legendary theatrical family, Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth|publisher=[[Simon & Schuster]]|location=New York|year=1992|isbn=0-671-76713-5|page=23}}</ref> They purchased a {{convert|150|acre|0|sing=on}} farm near [[Bel Air, Harford County, Maryland|Bel Air]] in [[Harford County, Maryland]], where John Wilkes Booth was born on May 10, 1838, the ninth of ten children. He was named after the English [[Radicalism (historical)|radical]] politician [[John Wilkes]], a distant relative.<ref>Smith, p. 18.</ref><ref>Booth's uncle Algernon Sydney Booth was the great-great-great-grandfather of [[Cherie Blair]] (née Booth), wife of former [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|British Prime Minister]] [[Tony Blair]].{{spaces|2}}–{{spaces|2}}{{cite web|last=Westwood|first= Philip|title=The Lincoln-Blair Affair|url=http://www.genealogytoday.com/uk/columns/westwood/021025.html |publisher=Genealogy Today|year=2002|accessdate=2009-02-02}}{{spaces|2}}–{{spaces|2}}{{cite web|last=Coates|first=Bill |title=Tony Blair and John Wilkes Booth |url=http://www.maderatribune.com/life/lifeview.asp?c=193252 |work=Madera Tribune |date=August 22, 2006|accessdate=2009-02-02}}</ref> Junius Brutus Booth's wife, Adelaide Delannoy Booth, was granted a divorce in 1851 on grounds of adultery, and Holmes legally wed John Wilkes Booth's father on May 10, 1851, the youth's 13th birthday.<ref>Smith, pp. 43–44.</ref> Booth's father built Tudor Hall on the Harford County property as the family's summer home, while also maintaining a winter residence on Exeter Street in Baltimore in the 1840s–1850s.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kimmel|first=Stanley|title=The Mad Booths of Maryland|publisher=Dover|location=New York|year=1969|id={{LCCN|69||019162}}|page=68}}</ref><ref name=Sun1931>{{cite news|last=McCardell|first=Lee|title=The body in John Wilkes Booth's grave|work=[[The Baltimore Sun]]|date=December 27, 1931}}</ref><ref>John Wilkes Booth's boyhood home, Tudor Hall, still stands on [[Maryland Route 22]] near Bel Air. It was acquired by Harford County in 2006, to be eventually opened to the public as a historic site and museum (reference: "Harford expected to OK renovation of Booth home." ''[[The Baltimore Sun]]''. September 8, 2008, p. 4).</ref> |

||

[[Image:Tudor Hall.jpg|thumb|left|"Tudor Hall" in 1865]] |

[[Image:Tudor Hall.jpg|thumb|left|"Tudor Hall" in 1865]] |

||

Revision as of 18:51, 2 April 2009

John Wilkes Booth | |

|---|---|

John Wilkes Booth | |

| Born | May 10, 1838 |

| Died | April 26, 1865 (aged 26) Port Royal, Virginia, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Known for | Assassination of Abraham Lincoln |

| Parent(s) | Junius Brutus Booth and Mary Ann Holmes |

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. Booth was a member of the prominent 19th century Booth theatrical family from Maryland and, by the 1860s, was a popular actor, well known in both the Northern United States and the South.[1] He was also a Confederate sympathizer vehement in his denunciation of the Lincoln Administration and outraged by the South's defeat in the American Civil War. He strongly opposed the abolition of slavery in the United States and Lincoln's proposal to extend voting rights to recently emancipated slaves.

Booth and a group of co-conspirators he led planned to kill Abraham Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward in a desperate bid to help the Confederacy's cause. Although Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had surrendered four days earlier, Booth believed the war was not yet over because Confederate General Joseph Johnston's army was still fighting the Union Army. Of the conspirators, only Booth was completely successful in carrying out his part of the plot—Lincoln died the next morning from a single gunshot wound to the back of the head, becoming the first American president to be assassinated.

Following the shooting, Booth fled on horseback to southern Maryland. He eventually made his way to a farm in rural northern Virginia; he was tracked down and killed by Union soldiers twelve days later. Eight others were tried and convicted, and four were hanged shortly thereafter. Over the years, various authors have suggested that Booth might have escaped his pursuers and subsequently died many years later under a pseudonym.

Background and early life

Booth's parents, the noted British Shakespearean actor Junius Brutus Booth and his mistress Mary 'dlskajfklasujiewrjk jasdklfjal;fjk Holmes, came to the United States from England in June 1821.[2] They purchased a 150-acre (61 ha) farm near Bel Air in Harford County, Maryland, where John Wilkes Booth was born on May 10, 1838, the ninth of ten children. He was named after the English radical politician John Wilkes, a distant relative.[3][4] Junius Brutus Booth's wife, Adelaide Delannoy Booth, was granted a divorce in 1851 on grounds of adultery, and Holmes legally wed John Wilkes Booth's father on May 10, 1851, the youth's 13th birthday.[5] Booth's father built Tudor Hall on the Harford County property as the family's summer home, while also maintaining a winter residence on Exeter Street in Baltimore in the 1840s–1850s.[6][7][8]

As a boy, John Wilkes Booth attended the Bel Air Academy, where the headmaster described him as "[n]ot deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time".[9][10] In 1850–1851, he attended the Quaker-run Milton Boarding School for Boys located in Sparks, Maryland and later St. Timothy's Hall, an Episcopal school in Catonsville, Maryland, beginning when he was 13 years old.[11][12]

While attending the Milton Boarding School, the youth met a Gypsy fortune-teller who read his palm and pronounced a grim destiny, telling Booth that he would have a grand but short life, doomed to die young and "meeting a bad end".[13] According to his sister, Booth wrote down the palm-reader's prediction and showed it to his family, often discussing its portents in moments of melancholy in later years.[13]

As recounted by Booth's sister, Asia Booth Clarke, in her memoirs written in 1874, no one church was preeminent in the Booth household. Booth's mother was Episcopalian and his father was described as a free spirit, preferring a Sunday walk along the Baltimore waterfront with his children to attending church. On January 23, 1853, the 14-year-old Booth was finally baptized at St. Timothy's Episcopal Church.[13]

By the age of 16, Booth was interested in the theatre and in politics, becoming a delegate from Bel Air to a rally by the Know Nothing Party for Henry Winter Davis, the anti-immigrant party's candidate for Congress in the 1854 elections.[14] Aspiring to follow in the footsteps of his father (who had died in 1852) and his actor brothers, Edwin and Junius Brutus, Jr., Booth began practicing elocution daily in the woods around Tudor Hall and studying Shakespeare.[15]

Theatrical career

1850s

At age 17, Booth made his stage debut on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in Richard III at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.[16] The audience hissed at the inexperienced actor when he missed some of his lines.[16][17] He also began acting at Baltimore's Holliday Street Theater, owned by John T. Ford, where the Booths had performed frequently.[18] In 1857, Booth joined the stock company of the Arch Street Theatre in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he played for a full season.[19] At his request he was billed as "J.B. Wilkes", a pseudonym meant to avoid comparison with other members of his famous thespian family.[16][20] Author Jim Bishop wrote that Booth "developed into an outrageous scene stealer, but he played his parts with such heightened enthusiasm that the audiences idolized him".[17] In February 1858, he played in Lucrezia Borgia at the Arch Street Theatre. On opening night, he experienced stage fright and stumbled over his line. Instead of introducing himself by saying, "Madame, I am Petruchio Pandolfo", he stammered, "Madame, I am Pondolfio Pet—Pedolfio Pat—Pantuchio Ped—dammit! Who am I?", causing the audience to roar with laughter.[16][21]

Later that year, Booth played the part of an Indian, Uncas, in a play staged in Petersburg, Virginia, and then became a stock company actor at the Richmond Theatre in Virginia, where he became increasingly popular with audiences for his energetic performances.[22] On October 5, 1858, Booth played the part of Horatio in Hamlet, with his older brother Edwin having the title role. Afterward, Edwin led the younger Booth to the theatre's footlights and said to the audience, "I think he's done well, don't you?" In response, the audience applauded loudly and cried "Yes! Yes!"[22]

Called "the handsomest man in America" by some reviewers and noted for having an "astonishing memory", other critics were mixed in their estimation of his acting.[1][23] He stood 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic.[24] A contemporary described him as a "muscular, perfect man", with "curling hair, like a Corinthian capital".[25]

Booth's stage performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical, leaping upon the stage and gesturing with passion.[24][26] He was an excellent swordsman and a fellow actor once recalled that he occasionally cut himself with his own sword.[24]

Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", but that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development.[26] Author Gene Smith wrote that Booth's acting may not have been quite as precise as his brother Edwin's, but his strikingly handsome appearance enthralled women.[27] As the 1850s drew to a close, Booth was becoming wealthy as an actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to more than $500,000 in 2009).[28]

1860s

After finishing the 1859–1860 theatre season in Richmond, Virginia, Booth embarked on his first national tour as a leading actor. He engaged a Philadelphia attorney, Matthew Canning, to serve as his agent.[29] By mid-1860, he was playing in such cities as New York, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, Columbus, Georgia, Montgomery, Alabama, and New Orleans.[17][30] Poet and journalist Walt Whitman said of Booth's acting, "He would have flashes, passages, I thought of real genius".[31] The Philadelphia Press drama critic said, "Without having [his brother] Edwin's culture and grace, Mr. Booth has far more action, more life, and, we are inclined to think, more natural genius."[31] When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, Booth was starring in Albany, New York. His outspoken admiration for the South's secession, publicly calling it "heroic", so enraged local citizens that they demanded his banning from the stage for making "treasonable statements".[32] Albany's drama critics were kinder, however, giving him rave reviews. One called the Maryland actor a genius, praising his acting for "never fail[ing] to delight with his masterly impressions".[33] As the Civil War raged across the divided land in 1862, Booth appeared mostly in Union and border states. In January, he played Richard III in St. Louis and then made his Chicago debut. In March, he made his first acting appearance in New York City.[34] In May 1862, the popular actor made his Boston debut, playing nightly at the Boston Museum in Richard III (May 12, 15, and 23), Romeo and Juliet (May 13), The Robbers (May 14 and 21), Hamlet (May 16), The Apostate (May 19), The Stranger (May 20), and The Lady of Lyons (May 22). Following his performance of Richard III on May 12, the Boston Transcript's review the next day called Booth "the most promising young actor on the American stage".[35]

Starting in January 1863, he returned to the Boston Museum for a series of plays, including the role of the villain Duke Pescara in The Apostate that won acclaim from both audiences and critics.[36] Back in Washington in April, he played the title roles in Hamlet and Richard III, one of his favorites. Billed as "The Pride of the American People, A Star of the First Magnitude", the critics were equally enthusiastic. The National Republican drama critic said Booth "took the hearts of the audience by storm" and termed his performance "a complete triumph".[37][38] At the beginning of July 1863, Booth finished the acting season at Cleveland's Academy of Music, as the Battle of Gettysburg raged in Pennsylvania. Between September–November 1863, Booth played a hectic schedule in the northeast, appearing in Boston, Providence, Rhode Island, and Hartford, Connecticut.

When old Booth family friend John T. Ford opened 2,400-seat Ford's Theatre on November 9 in Washington, D.C., Booth was one of the first leading men to appear there, playing in Charles Selby's The Marble Heart.[39][40] In this play, Booth portrayed a Greek sculptor in costume, making marble statues come to life.[40] President Lincoln watched the play from his box. At one point during the performance, Booth was said to have shaken his finger in Lincoln's direction as he delivered a line of dialogue. Lincoln's sister-in-law, sitting with him in the same presidential box where he would later be slain, turned to him and said, "Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you".[41] The President replied, "He does look pretty sharp at me, doesn't he?".[41] On another occasion when Lincoln's son Tad saw Booth perform, he said the actor thrilled him, prompting Booth to give the President's youngest son a rose.[41] Booth ignored an invitation to visit Lincoln between acts, however.[41]

On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his two brothers, Edwin and Junius, in a single engagement production of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York.[42] He played Mark Antony and his brother Edwin had the larger role of Brutus in a performance acclaimed as "the greatest theatrical event in New York history".[41] The proceeds went towards a statue of Shakespeare for Central Park which still stands today.[42]

In January 1865, he acted in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet in Washington, again garnering rave reviews. The National Intelligencer enthused of Booth's Romeo, "the most satisfactory of all renderings of that fine character", especially praising the death scene.[43] Booth made the final appearance of his acting career at Ford's on March 18, 1865, when he again played Duke Pescara in The Apostate.[44]

Business ventures

Booth invested some of his growing wealth in various enterprises during the early 1860s, including land speculation in Boston's Back Bay section.[45] He also started a business partnership with John Ellsler, manager of the Cleveland Academy of Music, and another friend, Thomas Mears, to develop oil wells in northwestern Pennsylvania, where an oil boom had started in August 1859, following Edwin Drake's discovery of oil there.[46] Initially calling their venture Dramatic Oil (later renaming it Fuller Farm Oil), the partners invested in a 31.5-acre (12.7 ha) site along the Allegheny River at Franklin, Pennsylvania, in late 1863 for drilling.[46] By early 1864, they had a producing 1,900-foot (579 m) oil well, named Wilhelmina for Mears' wife, yielding 25 barrels of crude oil daily, considered a good yield at the time. The Fuller Farm Oil company was selling shares with a prospectus featuring the well-known actor's celebrity status as "Mr. J. Wilkes Booth, a successful and intelligent operator in oil lands", it said.[46] The partners, impatient to increase the well's output, attempted the use of explosives which wrecked the well and ended production. Booth, already growing more obsessed with the South's worsening situation in the Civil War and angered at Lincoln's re-election, withdrew from the oil business on November 27, 1864, with a substantial loss of his $6,000 investment.[46]

Civil War years

Strongly opposed to the abolitionists who sought to end slavery in the U.S., Booth attended the hanging on December 2, 1859, of abolitionist leader John Brown, who was executed for leading a raid on the Federal armory at Harpers Ferry (in present-day West Virginia).[47] Booth had been rehearsing at the Richmond Theatre when he abruptly decided to join the Richmond Grays, a volunteer militia of 1,500 men travelling to Charles Town for Brown's hanging, to guard against any attempt by abolitionists to rescue Brown from the gallows by force.[47] When Brown was hanged without incident, Booth stood in uniform near the scaffold and afterwards expressed great satisfaction with Brown's fate, although he admired the condemned man's bravery in facing death stoically.[48]

Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, and the following month Booth wrote a long speech that decried Northern abolitionism and made clear his strong support of the South and the institution of slavery. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War began, and eventually eleven Southern states seceded from the Union. Booth's family was from Maryland, a border state which remained in the Union during the war despite a slaveholding portion of the population that favored the Confederacy. Because the secession of Maryland would leave Washington, D.C. an indefensible enclave within the Confederacy, Lincoln declared martial law in Maryland and ordered the imprisonment of pro-secession Maryland political leaders at Ft. McHenry to prevent the state's secession, a move that many, including Booth, viewed as unconstitutional.[49]

As a popular actor in the 1860s, he continued to travel extensively to perform in both North and South, and as far west as New Orleans, Louisiana. According to his sister Asia, Booth confided to her that he also used his position to smuggle quinine to the South during his travels there, helping the Confederacy obtain the needed drug despite the Northern blockade.[45]

Although Booth was pro-Confederate, his family, like many Marylanders, was divided. He was outspoken in his love for the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred for Lincoln.[41][50] As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make any stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and President Lincoln.[45] In early 1863, Booth was arrested in St. Louis while on a theatre tour, when he was heard saying he "wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell".[51] Charged with making "treasonous" remarks against the government, he was released when he took an oath of allegiance to the Union and paid a substantial fine.

In February 1865, Booth became infatuated with Lucy Hale, the daughter of U.S. Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire, and they became secretly engaged when Booth received his mother's blessing for their marriage plans. "You have so often been dead in love," his mother counseled Booth in a letter, "be well assured she is really and truly devoted to you".[52] Booth composed a handwritten Valentine card for his betrothed on February 13, expressing his "adoration". She was unaware of Booth's deep antipathy towards President Lincoln.[52]

Plot to kidnap Lincoln

As the 1864 Presidential election drew near, the Confederacy's prospects for victory were ebbing and the tide of war increasingly favored the North. The likelihood of Lincoln's re-election filled Booth with rage towards the President, whom Booth blamed for the war and all of the South's troubles. Booth, who had promised his mother at the outbreak of war that he would not enlist as a soldier, increasingly chafed at not actually fighting for the South, confiding in his diary, "I have begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence".[53] He began to formulate plans to kidnap Lincoln from his summer residence at the Old Soldiers Home, three miles (5 km) from the White House, and to smuggle him across the Potomac River into Richmond. Once in Confederate hands, Lincoln would be exchanged for the release of Confederate Army prisoners of war held captive in Northern prisons and, Booth reasoned, bring the war to an end by emboldening opposition to the war in the North.[53][54][55] Throughout the Civil War, the Confederacy maintained a network of underground operators in southern Maryland, particularly Charles and St. Mary's counties, smuggling recruits across the Potomac River into Virginia and relaying messages for Confederate agents as far north as Canada.[56] Booth recruited his friends Samuel Arnold and Michael O'Laughlen as accomplices.[57] They met often at the house of Maggie Branson, a known Confederate sympathizer, at 16 North Eutaw Street in Baltimore.[18] He also met with several well-known Confederate sympathizers at The Parker House in Boston.

In October Booth made an unexplained trip to Montreal, which at the time was a well-known center of clandestine Confederate activity. He spent ten days in the city, staying for a time at St. Lawrence Hall, a rendezvous for the Confederate Secret Service, and meeting at least one blockade runner there. It is possible that it was here that he also met Confederate Secret Service director James D. Bulloch, as well as George Nicholas Sanders, a one-time U.S. ambassador to Britain.

No conclusive proof has linked Booth's kidnapping or assassination plots to a conspiracy involving the leadership of the Confederate government, although historians such as David Herbert Donald have said, "It is clear that, at least at the lower levels of the Southern secret service, the abduction of the Union President was under consideration".[58] Other writers exploring possible connections between Booth's planning and Confederate agents include Nathan Miller's Spying For America and William Tidwell's Come Retribution: the Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln.

After Lincoln's landslide re-election in early November 1864 on a platform advocating passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to abolish slavery altogether,[59] Booth devoted increasing energy and money to his kidnap plot. He assembled a loose-knit band of Southern sympathizers, including David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell (also known as Lewis Payne or Paine), and John Surratt, a rebel agent.[56] They began to meet routinely at the boarding-house of Surratt's mother, Mrs. Mary Surratt.

By this time, Booth was arguing so vehemently with his older, pro-Union brother Edwin about Lincoln and the war that Edwin finally told him he was no longer welcome at his New York home. Booth also railed against Lincoln in conversations with his sister Asia, saying, "That man's appearance, his pedigree, his coarse low jokes and anecdotes, his vulgar similes, and his policy are a disgrace to the seat he holds. He is made the tool of the North, to crush out slavery."[60] As the Confederacy's defeat became more certain in 1865, Booth decried the end of slavery and Lincoln's election to a second term, "making himself a king", the disgruntled actor fumed, in "wild tirades", his sister recalled.[61]

Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4 as the invited guest of his secret fiancée, Lucy Hale. In the crowd below were Powell, Atzerodt, and Herold. There was no attempt to assassinate Lincoln during the inauguration. Later, however, Booth remarked about his "excellent chance ... to kill the President, if I had wished".[53]

On March 17, Booth learned that Lincoln would be attending a performance of the play Still Waters Run Deep at a hospital near the Soldier's Home. Booth assembled his team on a stretch of road near the Soldier's Home in the attempt to kidnap Lincoln en route to the hospital, but the president did not appear.[62] Booth later learned that Lincoln had changed his plans at the last moment to attend a reception at the National Hotel in Washington where, coincidentally, Booth was staying at the time.[53]

Assassination of Lincoln

On April 12, 1865, after hearing the news that Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Booth told Louis J. Weichmann, a friend of John Surratt, and a boarder at Mary Surratt's house, that he was done with the stage and that the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Preserv'd. Weichmann did not understand the reference. Venice Preserv'd is about an assassination plot. With the Union Army's capture of Richmond and Lee's surrender, all of the territory south of Washington was controlled by Union forces. Booth's plan to kidnap Lincoln and smuggle the President south was no longer possible, so Booth changed his abduction scheme into one of assassination.[63]

The previous day, Booth was in the crowd outside the White House when Lincoln gave an impromptu speech from his window. When Lincoln stated that he was in favor of granting suffrage to the former slaves, Booth declared that it would be the last speech Lincoln would ever make.[62][64]

On the morning of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Booth learned that the President and Mrs. Lincoln would be attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. He immediately set about making plans for the assassination, which included making arrangements with livery stable owner James W. Pumphrey for a getaway horse, and an escape route. Booth informed Powell, Herold and Atzerodt of his intention to kill Lincoln. He assigned Powell to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward and Atzerodt to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson. Herold would assist in their escape into Virginia.[65]

By targeting Lincoln and his two immediate successors to the office, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion. Booth also planned to assassinate the Union commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant; however, Grant's wife had promised to visit family and so they were departing Washington by train that evening for New Jersey.[18] Booth had hoped that the assassinations would create sufficient chaos within the Union that the Confederate government could reorganize and continue the war.

As a famous and popular actor who had frequently performed at Ford's Theatre, and was well known to its owner John T. Ford, Booth had free access to all parts of the theater, even having his mail sent there.[66] By boring a spyhole into the door of the presidential box earlier that day, the assassin could check that his intended victim had made it to the play. That evening, at around 10 p.m., as the play progressed, John Wilkes Booth slipped into Lincoln's box and shot him in the back of the head with a .44 caliber Derringer. Booth's escape was almost thwarted by Major Henry Rathbone, who was present in the Presidential box with Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln.[67] Rathbone was stabbed by Booth when the startled officer lunged at the assassin.[56] Rathbone's fiancée, Clara Harris, who was also present in the box, was unhurt.

Booth then jumped from the President's box and fell to the stage, injuring his leg when it snagged on a U.S. Treasury Guard flag used for decoration.[68] Witnesses said he shouted "Sic semper tyrannis" (Latin for "Thus always to tyrants", attributed to Brutus at Caesar's assassination and the Virginia state motto) from the stage, while others said he added, "The South is avenged."[24][69]

Reaction and pursuit

In the ensuing pandemonium inside Ford's Theatre, Booth fled by a stage door to the alley, where his getaway horse was held for him by Joseph "Peanuts" Burroughs.[70] The owner of the horse had warned Booth that the horse was high spirited and would break halter if left unattended. Booth left the horse with Edmund Spangler and Spangler arranged for Burroughs to hold the horse.

The fleeing assassin galloped into southern Maryland, accompanied by David Herold, having planned his escape route to take advantage of the sparsely-settled area's lack of telegraphs and railroads and predominantly Confederate sympathies.[65][71] Its dense forests and swampy terrain made it ideal for an escape route into rural Virginia, he felt.[65] At midnight, Booth and Herold arrived at Surratt's Tavern on the Brandywine Pike, 9 miles (14 km) from Washington, where they had stored guns and equipment earlier in the year as part of the kidnap plot.[72]

The fugitives then continued southward, stopping before dawn on April 15 at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, 25 miles (40 km) from Washington, for treatment of Booth's painful, injured leg.[72] Booth told the physician the injury occurred when his horse fell, Mudd said later.[73] The next day, Booth and Herold arrived at the home of Samuel Cox. As the two fugitives hid in the woods nearby, Cox contacted Thomas A. Jones, his foster brother and a Confederate agent in charge of spy operations in the southern Maryland area since 1862.[56][74] By order of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the War Department advertised a $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of Booth and his accomplices, and Federal troops were dispatched to search southern Maryland extensively, following tips reported by Federal intelligence agents to Col. Lafayette Baker.[75]

While Federal troops combed the rural area's woods and swamps for Booth in the days following the assassination, the nation experienced an outpouring of grief. On Tuesday morning, April 18, mourners waited seven abreast in a mile-long line outside the White House for the public viewing of the slain president, reposing in his walnut casket in the black-draped East Room.[76] Thousands of mourners arriving on special trains jammed Washington for the next day's funeral, sleeping on hotel floors and even resorting to blankets spread outdoors on the capital's lawn.[77] Prominent abolitionist leader and orator Frederick Douglass called the assassination an "unspeakable calamity" for African-Americans.[78] Great indignation was directed towards Booth as the assassin's identity was telegraphed across the nation. Newspapers called him an "accursed devil", "monster", "madman", and a "wretched fiend".[79] Historian Dorothy Kunhardt wrote:

Almost every family who kept a photograph album on the parlor table owned a likeness of John Wilkes Booth of the famous Booth family of actors. After the assassination Northerners slid the Booth card out of their albums: some threw it away, some burned it, some crumpled it angrily."[80]

Even in the South, sorrow was expressed in some quarters. In Savannah, Georgia, where the mayor and city council addressed a vast throng at an outdoor gathering to express their indignation, many in the crowd wept.[81] Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston called Booth's act "a disgrace to the age".[82] Robert E. Lee also expressed regret at Lincoln's death by Booth's hand.[78]

Not all were grief-stricken, however. In New York City, a man was attacked by an enraged crowd when he shouted, "It served Old Abe right!" after hearing the news of Lincoln's death.[81] Elsewhere in the South, Lincoln was hated in death as in life, and Booth was viewed as a hero as many rejoiced at news of his deed.[78] Other Southerners feared that a vengeful North would exact a terrible retribution upon the defeated former Confederate states. "Instead of being a great Southern hero, his deed was considered the worst possible tragedy that could have befallen the South as well as the North", wrote Kunhardt.[83]

While hiding in the Maryland woods as he waited for an opportunity to cross the Potomac River into Virginia, Booth read the accounts of national mourning reported in the newspapers brought to him by Jones each day.[83] By Thursday, April 20, he was aware that some of his co-conspirators were already arrested: Mary Surratt, Powell (or Paine), Arnold, and O'Laughlen.[84] Booth was surprised to find little public sympathy for his action, and wrote of his dismay in a journal entry on April 21, as he awaited nightfall before crossing the Potomac River into Virginia (see map): "For six months we had worked to capture. But our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done. I struck boldly, and not as the papers say. I can never repent it, though we hated to kill". [85][86]

That same day, the funeral train bearing the body of Abraham Lincoln departed Washington for Baltimore on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the first stop on a 13-day journey to Springfield, Illinois, its final destination.[87] As the funeral train slowly made its way westward through seven states, stopping en route at Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Trenton, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus Ohio, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis during the following days, seven million people lined the railroad tracks along the 1,662-mile (2,675 km) route, holding aloft signs with legends such as "We mourn our loss", "He lives in the hearts of his people", and "The darkest hour in history".[88] In the cities where the train stopped, 1.5 million people viewed Lincoln in his coffin.[78][87][88] Aboard the train was Clarence Depew, president of the New York Central Railroad, who said, "As we sped over the rails at night, the scene was the most pathetic ever witnessed. At every crossroads the glare of innumerable torches illuminated the whole population, kneeling on the ground."[87] Dorothy Kunhardt called the funeral train's journey "the mightiest outpouring of national grief the world had yet seen".[89]

Meanwhile, as mourners were viewing Lincoln's remains when the funeral train steamed into Harrisburg, Booth and Herald were provided with a boat and compass by Jones, to cross the Potomac at night on April 21.[56] Instead of reaching Virginia, however, they mistakenly navigated upriver to a bend in the broad Potomac River, coming ashore again in Maryland on April 22.[90] The 23-year old Herold knew the area well, having frequently hunted there, and recognized a nearby farm as belonging to a Confederate sympathizer. The farmer led them to his son-in-law, Col. John J. Hughes, who provided the fugitives with food and a hideout until nightfall, for a second attempt to row across the river to Virginia.[91] Booth wrote in his diary, "With every man's hand against me, I am here in despair. And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for ... And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat".[91] The pair finally reached the Virginia shore near Machodoc Creek before dawn on Sunday, April 23.[92] There, they made contact with Thomas Harbin, whom Booth had previously brought into his erstwhile kidnapping plot. Harbin took Booth and Herold to another Confederate agent in the area, William Bryant, who supplied them with horses.[91][93]

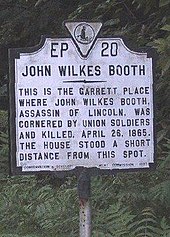

While Lincoln's funeral train was in New York City on Monday, April 24, Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty was dispatched from Washington with a detachment of 26 Union soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment to capture Booth in Virgina.[94] Accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Everton Conger, an intelligence officer assigned by Lafayette Baker, the detachment steamed 60 miles (97 km) down the Potomac River on a boat, the John S. Ide, landing at Belle Plain, Virginia.[94] The pursuers crossed the Rappahannock River and tracked Booth and Herold to Richard H. Garrett's farm, just south of Port Royal, Caroline County, Virginia. Booth and Herold had been led to the farm on April 24 by William S. Jett, a former private in the 9th Virginia Cavalry whom they had met before crossing the Rappahannock.[90] The Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination; Booth was introduced to them as "James W. Boyd", a Confederate soldier who, they were told, had been wounded in the battle of Petersburg and was returning home.[95]

Garrett's son, Richard, was an 11-year-old eyewitness. In later years, be became a Baptist minister and widely lectured on the events of Booth's demise at his family's farm.[95] In 1921, Garrett's lecture was published in the Confederate Veteran as the "True Story of the Capture of John Wilkes Booth".[96] According to his account, Booth and Herold arrived at the Garrett's farm, located on the road to Bowling Green, around 3 p.m. on Monday afternoon. Because Confederate mail delivery had ceased with the collapse of the Confederate government, he explained, the Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination.[96] After having dinner with the Garretts that evening, news of Gen. Johnston's surrender reached Booth. The last Confederate armed force of any size, its capitulation meant that the Civil War was unquestionably over and Booth's attempt to save the Confederacy by Lincoln's assassination had failed.[97] The Garretts also finally learned of Lincoln's death and the substantial reward for Booth's capture. Booth, said Garrett, displayed no reaction, other than to ask if the family would turn in the fugitive should they have the opportunity. Still not aware of their guest's true identity, one of the older Garrett sons averred that they might, if only because they needed the money. The next day, Booth told the Garretts he intended to reach Mexico, drawing a route on a map of theirs.[96] However, biographer Theodore Roscoe said of Garrett's account, "Almost nothing written or testified in respect to the doings of the fugitives at Garrett's farm can be taken at face value. Nobody knows exactly what Booth said to the Garretts, or they to him".[98]

Death

Conger tracked down Jett and interrogated him, learning of Booth's location at the Garrett farm. Before dawn on Wednesday, April 26, the soldiers caught up with the fugitives hiding in Garrett's tobacco barn. David Herold surrendered, but Booth refused Conger's demand to surrender, saying "I prefer to come out and fight", and the soldiers then set the barn on fire.[99][100] As Booth moved about inside the blazing barn, Sergeant Boston Corbett shot him. According to Corbett's later account, he fired at Booth because the fugitive "raised his pistol to shoot" at them.[100] Conger's report to Secretary Stanton, however, stated that Corbett shot Booth "without order, pretext or excuse", and recommended that Corbett be punished for disobeying orders to take Booth alive.[100] Booth, fatally wounded in the neck, was dragged from the barn to the porch of Garrett's farmhouse, where he died three hours later, at age 26.[95] The bullet had pierced three vertebrae and severed his spinal cord, paralyzing him.[101][99] In his last dying moments, he reportedly whispered "tell my mother I died for my country".[95][99] Asking that his hands be raised to his face so he could see them, Booth uttered his last words, "Useless, useless," and died as dawn was breaking.[99][102] In Booth's pockets were found a compass, a candle, pictures of five women including his fiancée Lucy Hale, and his diary, where he had written of Lincoln's death, "Our country owed all her troubles to him, and God simply made me the instrument of his punishment."[103]

Shortly after Booth's death, his brother Edwin wrote to his sister Asia, "Think no more of him as your brother; he is dead to us now, as he soon must be to all the world, but imagine the boy you loved to be in that better part of his spirit, in another world."[104] Asia also had in her possession a sealed letter which Booth had given her in January 1865 for safekeeping, only to be opened upon his death.[105] In the letter, Booth had written:

"I know how foolish I shall be deemed for undertaking such a step as this, where, on one side, I have many friends and everything to make me happy ... to give up all ... seems insane; but God is my judge. I love justice more than I do a country that disowns it, more than fame or wealth."[106]

Booth's letter, seized along with other family papers at Asia's house by Federal troops and published by The New York Times while the manhunt was underway, explained his reasons for plotting against Lincoln. In it he said, "I have ever held the South was right. The very nomination of Abraham Lincoln, four years ago, spoke plainly war upon Southern rights and institutions".[107] The institution of "African slavery", he had written, "is one of the greatest blessings that God has ever bestowed upon a favored nation" and Lincoln's policy was one of "total annihilation".[107]

Aftermath

John Wilkes Booth's body was taken aboard the ironclad USS Montauk and brought to the Washington Navy Yard for identification and an autopsy. The body was identified there as Booth's by more than ten people who knew him.[108] Among the identifying features used to make sure that the man that was killed was Booth was a tattoo on his left hand with his initials J.W.B., and a very distinct scar on the back of his neck.[109] The third, fourth, and fifth vertebrae were removed during the autopsy to allow access to the bullet. These bones are still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C.[110] The body was then buried in a storage room at the Old Penitentiary, later moved to a warehouse at the Washington Arsenal on October 1, 1867.[111] In 1869, the remains were once again identified before being released to the Booth family, where they were buried in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, after a burial ceremony conducted by Fleming James, minister of Christ Episcopal Church, in the presence of more than 40 people.[111][112][113][114] By then, wrote scholar Russell Conwell after visiting homes in the vanquished former Confederate states, hatred of Lincoln still smoldered and "Photographs of Wilkes Booth, with the last words of great martyrs printed upon its borders ... adorn their drawing rooms".[78]

Eight others implicated in Lincoln's assassination were tried by a military tribunal in Washington, D.C., and found guilty on June 30, 1865.[115] Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were hanged in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7, 1865.[116] Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O'Laughlen were sentenced to life imprisonment at Fort Jefferson in Florida's Dry Tortugas; Edmund Spangler was given a six-year term in prison.[52] O' Laughlen died in a yellow fever epidemic there in 1867. The others were eventually pardoned in February 1869 by President Andrew Johnson.[117]

Forty years later, when the centennial of Lincoln's birth was celebrated in 1909, a border state official reflected on Booth's assassination of Lincoln, "Confederate veterans held public services and gave public expression to the sentiment, that 'had Lincoln lived' the days of reconstruction might have been softened and the era of good feeling ushered in earlier".[78]

Theories of Booth's escape

In 1907, Finis L. Bates wrote Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, contending that a Booth look-alike was mistakenly killed at the Garrett farm while Booth eluded his pursuers.[118] Booth, said Bates, assumed the pseudonym "John St. Helen" and died in 1903 at Enid, Oklahoma, after making a deathbed confession that he was the fugitive assassin.[7][118] By 1913, more than 70,000 copies of the book had been sold, and Bates exhibited St. Helen's mummified body in carnival sideshows.[7]

In response, the Maryland Historical Society published an account in 1913 by then-Baltimore mayor William M. Pegram, who had viewed Booth's remains upon the casket's arrival at the Weaver funeral home in Baltimore on February 18, 1869, for burial at Green Mount Cemetery. Pegram, who had known Booth well as a young man, submitted a sworn statement that the body he had seen in 1869 was Booth's.[119] Others positively identifying this body as Booth at the funeral home included Booth's mother, brother, and sister, along with his dentist and other Baltimore acquaintances.[7] Earlier, The New York Times had published an account by their reporter in 1911 detailing the burial of Booth's body at the cemetery and those who were witnesses.[112]

The Lincoln Conspiracy, a book published in 1977, contended there was a government plot to conceal Booth's escape, reviving interest in the story and prompting the display of St. Helen's mummified body in Chicago that year.[120] The book sold more than one million copies and was made into The Lincoln Conspiracy movie.[121] A 1998 book, The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth, contended that Booth had escaped, sought refuge in Japan and eventually returned to the United States.[122] In 1994 two historians, together with several descendants, sought a court order for the exhumation of Booth's body at Green Mount Cemetery, which was, according to their lawyer, "intended to prove or disprove longstanding theories on Booth's escape" by conducting a photo-superimposition analysis.[123][124] The application was blocked, however, by Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Joseph H. H. Kaplan, who cited, among other things, "the unreliability of petitioners' less-than-convincing escape/cover-up theory" as a major factor in his decision. The Maryland Court of Special Appeals upheld the ruling.[125] No gravestone marks the precise location where Booth is buried in the family's gravesite. Author Francis Wilson, 11–years old at the time of Lincoln's assassination, wrote an epitaph of Booth in his 1929 book John Wilkes Booth: "In the terrible deed he committed, he was actuated by no thought of monetary gain, but by a self-sacrificing, albeit wholly fanatical devotion to a cause he thought supreme".[126]

The capture of Booth was the subject of an episode of the CBS educational series You Are There, hosted by Walter Cronkite.

Notes

- ^ a b Clarke, Asia Booth (1996). Terry Alford (ed.). John Wilkes Booth: A Sister's Memoir. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. ix. ISBN 0-87805-883-4.

- ^ Smith, Gene (1992). American Gothic: the story of America’s legendary theatrical family, Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 0-671-76713-5.

- ^ Smith, p. 18.

- ^ Booth's uncle Algernon Sydney Booth was the great-great-great-grandfather of Cherie Blair (née Booth), wife of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. – Westwood, Philip (2002). "The Lincoln-Blair Affair". Genealogy Today. Retrieved 2009-02-02. – Coates, Bill (August 22, 2006). "Tony Blair and John Wilkes Booth". Madera Tribune. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ Smith, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Kimmel, Stanley (1969). The Mad Booths of Maryland. New York: Dover. p. 68. LCCN 69-0.

- ^ a b c d McCardell, Lee (December 27, 1931). "The body in John Wilkes Booth's grave". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ John Wilkes Booth's boyhood home, Tudor Hall, still stands on Maryland Route 22 near Bel Air. It was acquired by Harford County in 2006, to be eventually opened to the public as a historic site and museum (reference: "Harford expected to OK renovation of Booth home." The Baltimore Sun. September 8, 2008, p. 4).

- ^ Kimmel, p. 70.

- ^ The Bel Air Academy, originally the Harford Academy founded in 1814, is the forerunner of today's Bel Air High School.

- ^ Clarke, pp. 39–40.

- ^ The Milton Boarding School building in Sparks, Md., which John Wilkes Booth once attended, still stands and is now the Milton Inn restaurant.

- ^ a b c Clarke, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Smith, p. 60.

- ^ Smith, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Smith, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Bishop, Jim (1955). The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Harper & Row. pp. 63–64. LCCN 54-0.

- ^ a b c Baltimore During the Civil War. Linthicum, Md.: Toomey Press. 1997. pp. 77–79. ISBN 0-9612670-7-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Kimmel, p. 149.

- ^ The Lincoln Conspiracy. Buccaneer. 1994. p. 24. ISBN ISBN 1-56849-531-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Kimmel, p. 150.

- ^ a b Kimmel, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Bishop, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 585. ISBN 0-684-80846-3.

- ^ Townsend, George Alfred (1865). The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald. p. 26. ISBN 978-0976480532.

- ^ a b Thomas, Benjamin P. (1952). Abraham Lincoln, a Biography. New York: Knopf. p. 519. LCCN 52-0.

- ^ Smith, pp. 71–72.

- ^ "Relative Value of a US Dollar Amount 1774 to Present". Measuringworth. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Kimmel, p. 157.

- ^ Smith, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Smith, p. 80.

- ^ Kimmel, p. 159.

- ^ Smith, p. 86.

- ^ Kimmel, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Wilson, Francis (1972). John Wilkes Booth. New York: Blom. pp. 39–40. LCCN 74-0.

- ^ Kimmel, p. 170.

- ^ Smith, p. 97.

- ^ Kimmel, p. 172.

- ^ Smith, p. 101.

- ^ a b Kunhardt, Jr., A New Birth of Freedom, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f Kunhardt, Jr., Philip (1983). A New Birth of Freedom. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 342–343. ISBN 0-316-50600-1.

- ^ a b Smith, p. 105.

- ^ Kimmel, p. 177.

- ^ Clarke, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Clarke, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b c d Lockwood, John (March 1, 2003). "Booth's oil-field venture goes bust". The Washington Times.

- ^ a b Allen, Thomas B. (1992). The Blue and the Gray. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 41. ISBN 0870448765.

- ^ Smith, p. 80.

- ^ Kauffman, Michael W. (2004). American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. New York: Random House. pp. 104–114. ISBN 037550785X.

- ^ Lorant, Stefan (1954). The Life of Abraham Lincoln. New American Library. p. 250. LCCN 56-0.

- ^ Smith, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Twenty Days. North Hollywood, Calif.: Newcastle. 1965. p. 202. LCCN 62-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Ward, Geoffrey C. (1990). The Civil War – an illustrated history. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 361–363. ISBN 0-394-56285-2.

- ^ Smith, p. 109.

- ^ Wilson, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e Toomey, Daniel Carroll. The Civil War in Maryland. Baltimore, Md.: Toomey Press. pp. 149–151. ISBN 0-9612670-0-3.

- ^ Bishop, p. 72.

- ^ Donald, p. 587.

- ^ Kunhardt III, Philip B. (February 2009). "Lincoln's Contested Legacy". Smithsonian. 39 (11). Smithsonian Institution: p. 38.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Clarke, p. 88.

- ^ Clarke, p. 89.

- ^ a b Donald, p. 588.

- ^ Stern, Philip Van Doren (1955). The Man Who Killed Lincoln. Garden City, NY: Dolphin. p. 20. LCCN 99-0.

- ^ Wilson, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Townsend, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Bishop, p. 102.

- ^ Townsend, p. 7.

- ^ One historian, Michael W. Kauffman, in his book American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies (ISBN 0-375-75974-3) written in 2004, contends that Booth actually broke his leg when his horse fell on him later in the escape, and that Booth's diary entry claiming it occurred jumping to the stage is a typical Booth dramatization.

- ^ Smith, p. 154.

- ^ Pitman, Benn, ed. (1865). The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin. p. vi.

- ^ Bishop, p. 66.

- ^ a b Smith, p. 174.

- ^ Mudd, Samuel A. (1906). Mudd, Nettie (ed.). The Life of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd (4th ed.). New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company. pp. 20–21, 316–318.

- ^ Balsiger and Sellier, Jr., p. 191.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, pp. 106–107. The 26 soldiers who caught Booth were eventually awarded $1,653.85 each by Congress, along with $5,250 for Lieut. Doherty who led the detachment and $15,000 for Col. Lafayette Baker.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 120.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e f Kunhardt III, Philip B., "Lincoln's Contested Legacy", Smithsonian, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Smith, p. 184.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 107.

- ^ a b Kunhardt, Twenty Days, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Allen, p. 309.

- ^ a b Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 203.

- ^ Stern, p. 251.

- ^ Smith, p. 187.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Hansen, Peter A. (February 2009). "The funeral train, 1865". Trains. 69 (2). Kalmbach: 34–37. ISSN 0041-0934.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Smith, p. 192.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, p. 139.

- ^ a b "John Wilkes Booth's Escape Route". Ford's Theatre, National Historic Site. National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ a b c Smith, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Kimmel, pp. 238–240.

- ^ Stern, p. 279.

- ^ a b Smith, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c d "John Wilkes Booth's Last Days". The New York Times. July 30, 1896. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ^ a b c Garrett, Richard Baynham (October 1963). Fleet, Betsy (ed.). "A Chapter of Unwritten History: Richard Baynham Garrett's Account of the Flight and Death of John Wilkes Booth". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 71, No. 4. Virginia Historical Society. pp. pp. 391–395.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Stern, p. 306.

- ^ Theodore Roscoe, The Web of Conspiracy (New York, 1959, p. 376), footnoted in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 71, No. 4 (October, 1963), Virginia Historical Society, p. 391.

- ^ a b c d Smith, pp. 210–213.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Byron B. (1914). John Wilkes Booth and Jefferson Davis – a true story of their capture. Boston: The Lincoln & Smith Press. pp. 35–36.

- ^ Townsend, p. 37.

- ^ Hanchett, William (1986). The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies. University of Illinois Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 0252013611.

- ^ Donald, p. 597.

- ^ Clarke, p. 92.

- ^ Bishop, p. 70.

- ^ Bishop, p. 72.

- ^ a b "The murderer of Mr. Lincoln". The New York Times. April 21, 1865.

- ^ Kunhardt, Twenty Days, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Kauffman, Michael W. (2004). American Brutus:John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House. p. 394

- ^ Schlichenmeyer, Terri (August 21, 2007). "Missing body parts of famous people". CNN. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ a b Smith, pp. 239–241.

- ^ a b Freiberger, Edward (February 26, 1911). "Grave of Lincoln's Assassin Disclosed at Last". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ^ Kauffman, Michael W. (1978). "Fort Lesley McNair and the Lincoln Conspirators". Lincoln Herald. 80: pp. 176–188.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "On the 18th of February, 1869, Booth's remains were deposited in Weaver's private vault at Green Mount Cemetery awaiting warmer weather for digging a grave. Burial occurred in Green Mount Cemetery on June 22, 1869. Booth was an Episcopalian, and the ceremony was conducted by the Reverend Minister Fleming, James of Christ Episcopal Church, where Weaver was a sexton." (T. 5/25/95 at p. 117; Ex. 22H). Gorman & Williams Attorneys at Law: Sources on the Wilkes Booth case. The Court of Special Appeals of Maryland (September 1995), No. 1531;

- ^ Steers, Jr., Edward (2001). Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 222–7. ISBN 9780813191513.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Kunhardt, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Smith, p. 239.

- ^ a b Bates, Finis L. (1907). Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth. Atlanta, Ga.: J. L. Nichols. pp. 5–6. LCCN 45-0.

- ^ Pegram, William M. (1913). "The body of John Wilkes Booth". Journal. Maryland Historical Society: pp. 1–4.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Dredging up the John Wilkes Booth body argument". The Baltimore Sun. December 13, 1977. pp. B1–B5.

- ^ Balsiger and Sellier, Jr., front cover.

- ^ Nottingham, Theodore J. (1998). The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth. Sovereign. p. iv. ISBN 1-58006-021-8.

- ^ "New Scrutiny on John Wilkes Booth". The New York Times. October 24, 1994. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Kauffman, Michael (May–June 1995). "Historians Oppose Opening of Booth Grave". Civil War Times.

- ^ Gorman, Francis J. (1995). "Exposing the myth that John Wilkes Booth escaped". Gorman and Williams. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ Wilson, p. 19.

References

- Allen, Thomas B. (1992). The Blue and the Gray. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0870448765.

- The Lincoln Conspiracy. Buccaneer. 1994. ISBN 1-56849-531-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Bates, Finis L. (1907). Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth. Atlanta, Ga.: J. L. Nichols. LCCN 45-0.

- Bishop, Jim (1955). The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Harper & Row. LCCN 54-0.

- Clarke, Asia Booth (1996). Terry Alford (ed.). John Wilkes Booth: A Sister's Memoir. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-87805-883-4.

- Coates, Bill (August 22, 2006). "Tony Blair and John Wilkes Booth". Madera Tribune.

- Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80846-3.

- Freiberger, Edward (February 26, 1911). "Grave of Lincoln's Assassin Disclosed at Last". The New York Times.

- Garrett, Richard Baynham (October 1963). Fleet, Betsy (ed.). "A Chapter of Unwritten History: Richard Baynham Garrett's Account of the Flight and Death of John Wilkes Booth". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 71, No. 4. Virginia Historical Society.

- Gorman, Francis J. (1995). "Exposing the myth that John Wilkes Booth escaped". Gorman and Williams.

- Hanchett, William (1986). The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252013611.

- Hansen, Peter A. (February 2009). "The funeral train, 1865". Trains. 69 (2). Kalmbach. ISSN 0041-0934.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Johnson, Byron B. (1914). John Wilkes Booth and Jefferson Davis – a true story of their capture. Boston: The Lincoln & Smith Press.

- Kauffman, Michael W. (2004). American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. New York: Random House. ISBN 037550785X.

- Kauffman, Michael W. (1978). "Fort Lesley McNair and the Lincoln Conspirators". Lincoln Herald. 80.

- Kauffman, Michael W. (May–June 1995). "Historians Oppose Opening of Booth Grave". Civil War Times.

- Kimmel, Stanley (1969). The Mad Booths of Maryland. New York: Dover. LCCN 69-0.

- Twenty Days. North Hollywood, Calif.: Newcastle. 1965. LCCN 62-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Kunhardt, Jr., Philip (1983). A New Birth of Freedom. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-50600-1.

- Kunhardt III, Philip B. (February 2009). "Lincoln's Contested Legacy". Smithsonian. 39 (11).

- Lockwood, John (March 1, 2003). "Booth's oil-field venture goes bust". The Washington Times.

- Lorant, Stefan (1954). The Life of Abraham Lincoln. New American Library. LCCN 56-0.

- McCardell, Lee (December 27, 1931). "The body in John Wilkes Booth's grave". The Baltimore Sun.

- Mudd, Samuel A. (1906). Mudd, Nettie (ed.). The Life of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd (4th ed.). New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company.

- "John Wilkes Booth's Escape Route". Ford's Theatre, National Historic Site. National Park Service. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Nottingham, Theodore J. (1998). The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth. Sovereign. ISBN 1-58006-021-8.

- Pegram, William M. (1913). "The body of John Wilkes Booth". Journal. Maryland Historical Society.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Schlichenmeyer, Terri (August 21, 2007). "Missing body parts of famous people". CNN.

- Baltimore During the Civil War. Linthicum, Md.: Toomey Press. 1997. ISBN 0-9612670-7-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Smith, Gene (1992). American Gothic: the story of America’s legendary theatrical family, Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-76713-5.

- Steers, Jr., Edward (2001). Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813191513.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Stern, Philip Van Doren (1955). The Man Who Killed Lincoln. Garden City, NY: Dolphin. LCCN 99-0.

- "Dredging up the John Wilkes Booth body argument". The Baltimore Sun. December 13, 1977.

- "Harford expected to OK renovation of Booth home". The Baltimore Sun. September 8, 2008.

- Thomas, Benjamin P. (1952). Abraham Lincoln, a Biography. New York: Knopf. LCCN 52-0.

- "The murderer of Mr. Lincoln". The New York Times. April 21, 1865.

- "John Wilkes Booth's Last Days". The New York Times. July 30, 1896.

- "New Scrutiny on John Wilkes Booth". The New York Times. October 24, 1994.

- Toomey, Daniel Carroll. The Civil War in Maryland. Baltimore, Md.: Toomey Press. ISBN 0-9612670-0-3.

- Townsend, George Alfred (1865). The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald. ISBN 978-0976480532.

- Ward, Geoffrey C. (1990). The Civil War – an illustrated history. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-56285-2.

- Westwood, Philip (2002). "The Lincoln-Blair Affair". Genealogy Today.

- Wilson, Francis (1972). John Wilkes Booth. New York: Blom. LCCN 74-0.

Further reading

- Bak, Richard (1954). The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Dallas, Texas: Taylor. ISBN 0878332006.

- Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University. ISBN 0253345677.

- Reck, W. Emerson (1987). A. Lincoln: His Last 24 Hours. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0899502164.

- Swanson, James L. (2006). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0060518499.

- Turner, Thomas R. (1999). The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger. ISBN 1575240033.

For younger readers

- Giblin, James Cross (2005). Good Brother, Bad Brother. New York: Clarion. ISBN 0-618-09642-6.

External links

- Autopsy

- Lieut. Doherty's report to the War Department on 29 April 1865, recounting Booth's capture

- Booth: Escape and wanderings until final ending of the trail by suicide at Enid, Oklahoma, January 12, 1903 (1922) Digitized by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library

- The life, crime, and capture of John Wilkes Booth, with a full sketch of the conspiracy of which he was the leader, and the pursuit, trial and execution of his accomplices (1865) Digitized by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library.

- "John Wilkes Booth FBI file". Federal Bureau of Investigation. October 17, 2006. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008.

These records contain correspondence dated 1922–1923 of William J. Burns, former Director of the Bureau of Investigation, concerning a theory that Booth lived many years after the assassination of President Lincoln.

- Geringer, Joseph (2008). "John Wilkes Booth: The Story of Abraham Lincoln's Murderer". truTV.

- Linder, Douglas (2002). "Last Diary Entry of John Wilkes Booth". University of Missouri–Kansas City.

- "Hunt for Abraham Lincoln's Assassin, John Wilkes Booth". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 2008.

- American assassins

- American stage actors

- Lincoln conspirators

- Abraham Lincoln

- Actors from Maryland

- People of Maryland in the American Civil War

- Burials at Green Mount Cemetery

- American Episcopalians

- People from Harford County, Maryland

- 1838 births

- 1865 deaths

- 19th-century actors

- English Americans

- Shakespearean actors

- Deaths by firearm in Virginia