John C. Calhoun: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Infobox_Vice_President |

{{Infobox_Vice_President |

||

| name= |

| name=POOPINHIEMER |

||

| image=JCCalhoun.jpg |

| image=JCCalhoun.jpg |

||

| nationality=American |

| nationality=American |

||

Revision as of 15:24, 20 January 2009

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

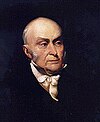

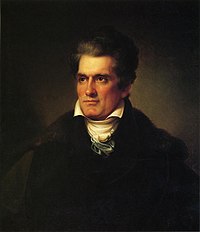

John Caldwell Calhoun (March 18, 1782 – March 31, 1850) was a leading United States Southern politician from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun was an advocate of slavery, states' rights, limited government, and nullification.

He was the second man to serve as Vice President under two administrations, (March 4, 1825 – December 28, 1832), under Presidents Adams and Jackson, born as a U.S. citizen (his predecessors were born before the revolution) and also the first Vice President to resign his office.

After a short stint in the South Carolina legislature, where he wrote legislation making South Carolina the first state to adopt universal suffrage for white men, Calhoun, barely 30, began his federal career as a staunch nationalist, favoring war with Britain in 1812. However, Calhoun's position changed in favor of states' rights following the "Corrupt Bargain" of 1824, by which, it is claimed, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Henry Clay gave the Presidency to John Quincy Adams in exchange for the position of United States Secretary of State.

It is said that by renouncing the Vice Presidency in 1832 for a Senate seat he obtained more power than he had under Jackson.

Although he died almost 11 years before the American Civil War broke out, Calhoun is considered to be an advocate of secession. Nicknamed the "cast-iron man" for his staunch determination to defend the causes in which he believed, Calhoun pushed nullification, under which states could declare null and void federal laws they deemed to be unconstitutional.[citation needed] He was an outspoken proponent of the institution of slavery, which he defended as a "positive good" rather than as a "necessary evil".[2] His rhetorical defense of slavery was partially responsible for escalating Southern threats of secession in the face of mounting abolitionist sentiment in the North. [citation needed] He was part of the "Great Triumvirate", or the "Immortal Trio", along with his colleagues Daniel Webster and Henry Clay.

He served in the United States House of Representatives (1810–1817) and was Secretary of War (1817–1824) under 5th U. S. President James Monroe and Secretary of State (1844–1845) under 10th U. S. President John Tyler.

Origins and early life

Calhoun was born on March 18 (or 19), 1782, the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun and his wife Martha (née Caldwell). His father was an Ulster-Scot who emigrated from County Donegal to the Thirteen Colonies where he met Martha, herself the daughter of a Protestant Irish immigrant father [3].

When his father became ill, the 17-year-old Calhoun quit school to continue the family farm. With his brothers' financial support, he later returned to his studies, earning a degree from Yale College in 1804. After studying law at the Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, Calhoun was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807. [citation needed]

In January 1811 Calhoun married his first cousin once removed, Floride Bonneau Colhoun, whose branch of the family spelled the surname differently than did his. The couple had 10 children over 8 years; three died in infancy. During her husband's second term as Vice President,under Andrew Jackson, starting 4 March 1829, Floride Calhoun, was a very conservative, staunch-in-public morals lady, and a central figure in the Petticoat Affair, which involved the 38-year-old Senator John Eaton.

Early political career

In 1810, Calhoun was elected to Congress, and became one of the War Hawks who, led by Henry Clay, were agitating for what became the War of 1812. Calhoun had made his public debut in calling for war after 1807's Chesapeake-Leopard affair.

After the war, J. C. Calhoun and H. Clay sponsored a Bonus Bill for public works. With the goal of building a strong nation that could fight a future war, he aggressively pushed for high protective tariffs (to build up industry), a national bank, internal improvements, and many other policies he later repudiated.[4]

It was 5th U. S. President James Monroe who appointed, in 1817, Calhoun to be Secretary of War, where he served until 1825, creating, unilaterally, the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1824, Calhoun was a reform-minded executive, who attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian department, but Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or rejected them.

As Belko (2004) argues, his management of Indian affairs proved his nationalism. His opponents were the "Old Republicans" in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for economy in the federal government; they often attacked the operations and finances of the War department. Calhoun became frustrated with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and ideological differences that dominated the late early republic.

Calhoun's nationalism also manifested itself in his advice to Monroe to sign off on the Missouri Compromise, which most other Southern politicians saw as a distinctly bad deal; Calhoun believed that continued agitation of the slavery issue threatened the Union, so the Missouri dispute had to be concluded. [citation needed]

As Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wrote in 1821, "Calhoun is a man of fair and candid mind, of honorable principles, of clear and quick understanding, of cool self-possession, of enlarged philosophical views, and of ardent patriotism. He is above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of this Union with whom I have ever acted."[5] Historian Charles Wiltse agrees, noting, "Though he is known today primarily for his sectionalism, Calhoun was the last of the great political leaders of his time to take a sectional position-later than Daniel Webster, later than Henry Clay, later than Adams himself. "[6]

Vice Presidency

Election

Calhoun originally was a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1824, but after failing to win the endorsement of the legislature in his own state, he decided to set his sights on the Vice Presidency, as no candidate received a majority in the Electoral College and the election was ultimately resolved by the House of Representatives.

Calhoun was elected Vice President in a landslide. Calhoun served four years under Adams, and then, in 1828, won re-election as Vice President alongside Andrew Jackson.

The Adams Administration

Calhoun's thoughts about Speaker of the House Henry Clay appointing John Quincy Adams as U. S. President as an outcome of the 1824 election, despite the greater popularity of Andrew Jackson, led him to feel, probably, unsatisfied because H. Clay got a significant slice of power, too, by such move.

Calhoun, it is said, resolved to thwart J. Q. Adams' and H. Clay's nationalist program, opposing it while holding power with them. In 1828, Calhoun ran for reelection as the running mate of Andrew Jackson, and thus became one of two Vice Presidents to serve under two Presidents (the other being George Clinton).

The Jackson Administration

Under Andrew Jackson, Calhoun's Vice Presidency remained controversial. Once again, a rift developed between Calhoun and the President, this time about hard cash.

The Tariff of 1828 (also known as the Tariff of Abominations) aggravated the rift between Calhoun and the Jacksonians. Calhoun had been assured that Jacksonians would reject the bill, but Northern Jacksonians were primarily responsible for its passage. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write South Carolina Exposition and Protest, an essay rejecting the nationalist philosophy he once advocated. [citation needed]

He now supported the theory of concurrent majority through the doctrine of nullification — that individual states could override federal legislation they deemed unconstitutional.[citation needed] Nullification traced back to arguments by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, which proposed that states could nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Jackson, who supported states rights but believed that nullification threatened the Union, opposed it. The difference between Calhoun's arguments and those of Jefferson and Madison is that Calhoun explicitly argued for a state's right to secede from the Union, if necessary, instead of simply nullifying certain federal legislation.

James Madison rebuked the nullificationists and said that no state had the right to nullify federal law.[7]

At the 1830 Jefferson Day dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel (April 13, 1830), Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed "Our federal Union, it must be preserved," to which Calhoun replied "the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear.[8]

In May 1830, the relationship between President Jackson and Vice - President Calhoun deteriorated further when Jackson discovered that Calhoun — while serving as James Monroe's Secretary of War, 1817 - 1823, — had requested President Monroe to censure Jackson (at the time a General) for invading Spanish Florida in 1818 during the Seminole War without authorization from either War Secretary Calhoun or President Monroe itself.

Calhoun defended his 1818 request, stating it was the right thing to do. [citation needed] The feud between him and Jackson heated up as Calhoun informed the President that another attack from his opponents was not hard for others to see, and would have a series of argumentative letters sent to each other - fueled by Jackson's opponents - until Jackson stopped the correspondence in July 1830.

By February 1831, the break between Calhoun and Jackson was final after Calhoun - responding to inaccurate press reports about the feud - published the letters in the United States Telegraph.[9]

More damage was done to Jackson and Calhoun's relationship after his wife, staunch and conservative Floride Calhoun, pregnant by her husband no less than 10 times, organized a coalition among Cabinet wives against Peggy Eaton, wife of 13th Secretary of War John Eaton. It was alleged that John and Peggy Eaton had engaged in an adulterous affair while Mrs. Eaton was still legally married to her first husband, John B. Timberlake; the allegations allegedly drove Timberlake to suicide, 1828.

The scandal, which became known as the Petticoat Affair or the Peggy Eaton Affair, resulted in the resignation of Jackson's Cabinet except for Postmaster General William T. Barry and Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren, (March 9, 1829 – resigned June 18, 1831), but only in order to take an alternative position in Jackson's administration as United States Ambassador to Britain, (1831 - 1832).

There, future 8th president Martin Van Buren, President (1839 - 1841), would have the assistance as a diplomat clerk of famous Hispanist, historian and writer, Washington Irving, (1783 - 1859).

Nullification Crisis

In 1832, the states' rights theory was put to the test in the Nullification Crisis after South Carolina passed an ordinance that nullified federal tariffs. The tariffs favored Northern manufacturing interests over Southern agricultural concerns, and the South Carolina legislature declared them to be unconstitutional. Calhoun had also formed a political party in South Carolina known as the Nullifier Party.

In response to the South Carolina move, Congress passed the Force Bill, which empowered the President to use military power to force states to obey all federal laws, and Jackson sent US Navy warships to Charleston harbor.

South Carolina then nullified the Force Bill. Tensions cooled after both sides agreed to the Compromise Tariff of 1833, a proposal by Senator Henry Clay to change the tariff law in a manner which satisfied Calhoun, who by then was in the Senate.

The irony in this is that Calhoun (anonymously, making his true opinions unknown to Jackson) argued for the doctrine of nullification, which had gone as far as to suggest secession. [citation needed] Calhoun had written the 1828 essay South Carolina Exposition and Protest, arguing that a state could veto any law it considered unconstitutional.[9]

The break between Jackson and Calhoun was complete, and in 1832, Calhoun ran for the Senate rather than remain as Vice President; because he exposed his nullification beliefs during the nullification crisis, his chances of becoming President were very low.[9] After the Compromise Tariff of 1833 went into effect, the Nullifier Party, along with other anti-Jackson politicians, formed a coalition known as the Whig Party. Calhoun sided with the Whigs until he broke with key Whig Senator Daniel Webster over slavery as well as the Whigs' program of "internal improvements", which many Southern politicians believe improved Northern industrial interests at the expense of Southern interests. Whig party leader, Henry Clay, sided with Daniel Webster on these issues.

U.S. Senator and views on slavery

On December 28, 1832, Calhoun accepted election to the United States Senate from his native South Carolina, becoming the first Vice President in U.S. history to resign from office, and the third Vice President to relinquish the office prior to its full term (Vice Presidents George Clinton and Elbridge Gerry both died in office). He would achieve his greatest influence and most lasting fame as a Senator.

Calhoun led the pro-slavery faction in the Senate in the 1830s and 1840s, opposing both abolitionism and attempts to limit the expansion of slavery into the western territories. [citation needed] He was also a major advocate of the Fugitive Slave Law, which enforced the co-operation of free states in returning escaping slaves.[citation needed] Calhoun couched his defense of Southern states' right to preserve the institution of slavery in terms of liberty and self-determination.

Whereas other Southern politicians had excused slavery as a necessary evil, in a famous February 1837 speech on the Senate floor, Calhoun went further, asserting that slavery was a "positive good." He rooted this claim on two grounds—white supremacy and paternalism. All societies, Calhoun claimed, are ruled by an elite group which enjoys the fruits of the labor of a less-privileged group.[2]

- "I may say with truth, that in few countries so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little exacted from him, or where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age. Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse."

The everlasting influence of Calhoun´s policies on his fierce defense of states' rights and support for the Slave Power, even in the 21st Century, proves that he played, even dead, a major role in deepening the growing divide between Northern and Southern states on this issue, wielding the threat of Southern secession to back slave state demands.

After a one year break as the 16th United States Secretary of State, (April 1, 1844 – March 10, 1845) under President John Tyler, being preceded by Abel P. Upshur and succeeded by James Buchanan, Calhoun returned to the Senate in 1845, participating in the epic Senate struggle over the expansion of slavery in the Western states, formerly Imperial Spanish - Mexican lands till as late as 1848, that produced the so called Compromise of 1850.

He died in March 1850, of tuberculosis in Washington, D.C., at the age of 68, and was buried in St. Philips Churchyard in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Calhoun Doctrine

Southerners challenged the doctrine of congressional authority to regulate or prohibit slavery in the territories. In 1847 Calhoun claimed that citizens from every state had the right to take their "property" to any territory. Congress, he asserted, had no authority to place restrictions on slavery in the territories. If the Northern majority continued to ride roughshod over the rights of the Southern minority, the Southern states would have little option but to secede.

Indian affairs

John C. Calhoun viewed the interactions with the American Indians as fundamental, feeling that having a separate, distinct culture within the borders of the United States would create problems in such areas as land usage, interracial relationships, and trade.

As a Secretary of War, (1817 - 1823), his "de facto" creation, in 1824, without the nation consent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and later twice as a Vice-President (1824 - 1832), provided him the tools allowing his "Indian Aborigines" policies and prejudices to be implemented in the United States as a whole, impairing thus the American Indian culture from existing inside the boundaries of what Calhoun saw as “white civilization".

He saw this difference between societies as a dominate versus subordinate relationship, implying either assimilate the Indians into American culture or move them West so they lived separated from white American society. Calhoun thought that the period for the Indian to be calmly assimilated had ended by the time he was appointed to the position of Secretary of War in 1817.

Such experiences as the battles of French settlers of New Orleans, Louisiana, against "The King of Spain Free Black Men Regiments from La Habana, Cuba" in the 1769 intervention of Spanish - Irish Commander Alejandro O´Reilly, (1722 - 1794), in the then considered as Spanish Louisiana, must have been ignored, too, by brought as Irish Protestants with Scotish ancestors Mr. and Mrs. Calhoun , no doubt at the end of their tether if they had ever heard about. The arrangements with the Seminola Indians of the region, probably were unknown to them also.

"Deep South brought" Calhoun probably thought it was in the best interests of both parties, the United States and the Indians, that Indians should move westward into the area west of Lake Michigan or into the area of the Louisiana Purchase. This, in his opinion, would allow the government to control the interactions between the Indians and the white Americans.

Conscious that nomadic buffaloe - hunting Indians would cease to exist if the United States did not take policies to remove them from the land that was coveted by the white Americans, he probably felt that Indian nomadic society could not survive. There seemed to be urgency in Calhoun’s writing. Either they "accepted" to become civilized, whatever that mean, or they would have to leave, for the moment being, as many "political solutions", somewhere else.

As Secretary of War under James Monroe, Calhoun and his department were authorized to make what they considered generous offers to Eastern tribes in exchange for their moving west of the Mississippi River. Some groups, such as some Cherokees accepted these offers. Other tribes, especially those that were not nomadic and had a connection to a specific area, refused the offers. These tribes were eventually relocated through removal. See:Trail of Tears

In any case, nomadic or no nomadic Indians would have to endure a white new inmigrants American presence in the aborigins lands at the Indian West.

The goal was to cut off the Indians’ trade with the British and allow the United States to monopolize the fur trade.

As stated above, Calhoun established the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824 as part of the War Department and he did this without congressional authorization. Congress did authorize a Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1832 after Calhoun had left the War Department.

This gave the War Department authority over all federal expenditures concerning Indians. In particular, they controlled the funds for the civilization of the Indians.

Ignoring XVIII Century European Philosophers believing naively on the "Good Savage Theories" he concentrated on using his real powers as Secretary of War, (1817 - circa 1824), and Vice-President, (1824 - 1832). He believed that government interference in the lives of Indians was essential because the Indians were too ignorant and uncivilized to be allowed to make their own decisions and live as they chose.

Legacy

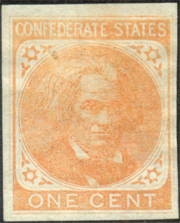

During the Civil War, the Confederate government honored Calhoun on a one-cent postage stamp, which was printed but never officially released (as seen below).

Calhoun was also honored by his alma mater, Yale University, naming one of its undergraduate residence halls "Calhoun College" and erecting a statue of Calhoun in Harkness Tower, a prominent campus landmark.

Clemson University campus, South Carolina, occupies the site of Calhoun's Fort Hill plantation, which he bequeathed to his wife and daughter, who promptly sold it to a relative along with 50 slaves, receiving $15,000 for the 1,100 acres (450 ha) and $29,000 for the slaves, some 600 USD apiece. When that owner died, Thomas Green Clemson foreclosed the mortgage as administrator of his mother-in-law's estate, thus regaining the property from his in-laws' widow.

Clemson's had served as U. S. Ambassador to Belgium — a post he obtained through the influence of his father-in-law, who was Secretary of State at the time. In 1888, after Calhoun's daughter died, Clemson wrote a will bequeathing his father-in-law's former estate to South Carolina on the condition that it be used for an agricultural university to be named "Clemson." A nearby town named for Calhoun was renamed Clemson in 1943.

There is also a Calhoun Community College in Decatur, Alabama, and Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Many streets in the South, such as John C. Calhoun Drive in Orangeburg, South Carolina and the John C. Calhoun Expressway in Augusta, GA, are named in his memory. [(Calhoun County, South Carolina), [Calhoun County, Georgia]], Calhoun County, Illinois, Calhoun County, Iowa , Calhoun County, Mississippi, and Calhoun County, Michigan are also named in his honor.

In 1957, United States Senators honored Calhoun as one of the "five greatest senators of all time."

Calhoun Middle School in Denton, Texas, too, is named after John C. Calhoun.

Calhoun also has a landing on the Santee-Cooper River in Santee, South Carolina, named after him. Calhoun Monument stands in Charleston, South Carolina. Calhoun Street, a large thoroughfare in Charleston was also named after Calhoun and the USS John C. Calhoun was a Fleet Ballistic Missile nuclear submarine, in commission from 1963 to 1994.

See also

Notes

- ^ Vision & Values in a Post-9/11 World: A curriculum on Civil Liberties, Patriotism, and the U.S. Role Abroad for Unitarian Universalist Congregations, Developed by Pamela Sparr on behalf of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations, Spring 2002. (Retrieved August 28, 2007)

- ^ a b http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Slavery_a_Positive_Good

- ^ wc.rootsweb.com

- ^ Wiltse (1944) vol 1 ch 8-11

- ^ Adams, Diary, V, 361

- ^ Wiltse, John C. Calhoun: Nationalist, 234

- ^ Rutland, Robert Allen. (1997) James Madison: The Founding Father, p.248-249.

- ^ Niven 173

- ^ a b c http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_John_Calhoun.htm

References

- Catherine Drew Gilpin Faust, 1st woman President, (2007), of Harvard University since 1672, The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South, (Louisiana State University Press, 1982) ISBN 978-0807116067

- James L. Roark Masters Without Slaves: Southern Planters in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Paperback), October 1978, Louisiana University, ISBN 0393009017 ISBN13 9780393009019)

- Belko, William S. John C. Calhoun and the Creation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs: An Essay on Political Rivalry, Ideology, and Policymaking in the Early Republic. South Carolina Historical Magazine 2004 105(3): 170-197. ISSN 0038-3082

Primary sources

- The Papers of John C. Calhoun Edited by Clyde N. Wilson; 28 volumes, University of South Carolina Press, 1959-2003. [1]; contains all letters, pamphlets and speeches by JCC and most letters written to him.

- speech in the Senate, January 13, 1834, -- "fanatics and madmen of the North" "No, Sir, State rights are no more."

- speech on the bill to continue the charter of the Bank of the United States, March 21, 1834

- speech on the Senate floor September 18, 1837, on the bill authorizing an issue of Treasury Notes

- speech on his amendment to separate the Government and the banks, October 3, 1837

- reply to Clay March 10, 1838, the Clay-Calhoun debate -- "Whatever the Government receives and treats as money, is money"

- Slavery a Positive Good, speech on the Senate floor, February 6, 1837.

- Calhoun, John C. Ed. H. Lee Cheek, Jr. Calhoun: Selected Writings and Speeches (Conservative Leadership Series), 2003. ISBN 0-89526-179-0.

- Calhoun, John C. Ed. Ross M. Lence, Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun, 1992. ISBN 0-86597-102-1.

- "Correspondence Addressed to John C. Calhoun, 1837-1849," Chauncey S. Boucher and Robert P. Brooks, eds., Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1929. 1931

Academic secondary sources

- Bartlett, Irving H. John C. Calhoun: A Biography (1993)

- Brown, Guy Story. "Calhoun's Philosophy of Politics: A Study of A Disquisition on Government"

- Capers; Gerald M. John C. Calhoun, Opportunist: A Reappraisal 1960.

- Capers Gerald M., "A Reconsideration of Calhoun's Transition from Nationalism to Nullification," Journal of Southern History, XIV (Feb., 1948), 34-48. online in JSTOR

- Cheek, Jr., H. Lee. Calhoun And Popular Rule: The Political Theory Of The Disquisition And Discourse. (2004) ISBN 0-8262-1548-3

- Ford Jr., Lacy K. Origins of Southern Radicalism: The South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860 (1988)

- Ford Jr., Lacy K. "Republican Ideology in a Slave Society: The Political Economy of John C. Calhoun, The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 54, No. 3 (Aug., 1988), pp. 405-424 in JSTOR

- Ford Jr., Lacy K. "Inventing the Concurrent Majority: Madison, Calhoun, and the Problem of Majoritarianism in American Political Thought," The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Feb., 1994), pp. 19-58 in JSTOR

- Gutzman, Kevin R. C., "Paul to Jeremiah: Calhoun's Abandonment of Nationalism," in _The Journal of Libertarian Studies_ 16 (2002), 3-33.

- Hofstadter, Richard. "Marx of the Master Class" in The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948)

- Niven, John. John C. Calhoun and the Price of Union (1988)

- Peterson, Merrill. The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (1987)

- Rayback Joseph G., "The Presidential Ambitions of John C. Calhoun, 1844-1848," Journal of Southern History, XIV (Aug., 1948), 331-56. online in JSTOR

- Wiltse, Charles M. John C. Calhoun, Nationalist, 1782-1828 (1944) ISBN 0-8462-1041-X; John C. Calhoun, Nullifier, 1829-1839 (1948); John C. Calhoun, Sectionalist, 1840-1859 (1951); the standard scholarly biography

External links

- United States Congress. "John C. Calhoun (id: C000044)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by John C. Calhoun at Project Gutenberg

- University of Virginia: John C. Calhoun - Timeline, quotes, & contemporaries, via University of Virginia

- Fort Hill house [2] at Clemson University.

- Other images via The College of New Jersey: [3], [4], [5]

- Response to Calhoun's Disquisition

- Find-A-Grave profile for John C. Calhoun

- Historical Marker: Patrick Calhoun Burial Grounds

- Vice Presidents of the United States

- United States Secretaries of State

- United States Secretaries of War

- United States Senators from South Carolina

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- Great Triumvirate

- Defenders of slavery

- American people of the War of 1812

- Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- American political theorists

- Andrew Jackson

- People from Abbeville County, South Carolina

- Scots-Irish Americans

- South Carolina lawyers

- American Unitarians

- Litchfield Law School alumni

- Deaths from tuberculosis

- 1782 births

- 1850 deaths

- Calhoun family

- Democratic Republicans

- South Carolina Democrats

- Infectious disease deaths in Washington, D.C.