Corpus separatum (Jerusalem)

| Jerusalem Corpus Separatum |

|---|

Corpus separatum (Latin for "separated body") was the internationalization proposal for Jerusalem and its surrounding area as part of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. It was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly with a two-thirds majority in November 1947. According to the Partition Plan, the city of Jerusalem would be brought under international governance, conferring it a special status due to its shared importance for the Abrahamic religions. The legal base ("Statute") for this arrangement was to be reviewed after ten years and put to a referendum. The corpus separatum was again one of the main issues of the post-war Lausanne Conference of 1949, besides the borders of Israel and the question of the Palestinian right of return.

The Partition Plan was not implemented, being firstly rejected by Palestinian and other Arab leaders and then overtaken by the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, which left Jerusalem split between Israel (West Jerusalem) and Jordan (East Jerusalem). In 2012, the European Parliament expressed majority support, and the UN General Assembly expressed overwhelming support for the view that Jerusalem should be a dual capital, with an even split between Israel and the State of Palestine,[1][2] although exact positions are varied.

Origin of the concept

The origins of the concept of corpus separatum or an international city for Jerusalem has its origins in the Vatican's long-held position on Jerusalem and its concern for the protection of the Christian holy places in the Holy Land, which predates the British Mandate. The Vatican's historic claims and interests, as well as those of Italy and France were based on the former Protectorate of the Holy See and the French Protectorate of Jerusalem.[citation needed]

Protection of non-Jewish rights

The Balfour Declaration, which expressed British support for the plan for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, also contained a proviso:

"it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine".

The Balfour Declaration, as well as the proviso, were incorporated in article 95 of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) and in the Mandate for Palestine (1923). Besides safeguarding the obvious interests of the non-Jewish inhabitants in Palestine, the claims of the Vatican and European powers were claimed to be covered by these provisos. These powers had officially lost all capitulation rights in the region by article 28 of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). The Palestinian Mandate also provided in articles 13 and 14 for an international commission to resolve competing claims on the holy places, but Britain never gave any effect to these articles.[citation needed]

Negotiations towards UN Partition Plan

During the negotiations in 1947 of proposals for a resolution for peace in Mandate Palestine, the Vatican, Italy and France revived their historic claims over the Christian holy places that they had lost in 1914 but expressed them as a call for a special international regime for the city of Jerusalem. The Vatican supported UN Resolution 181, which called for the “internationalisation” of Jerusalem. In the encyclical In multiplicibus curis (1948), Pope Pius XII expressed his wish that the holy places have “an international character”. The 15 May 1948 issue of L’Osservatore Romano, the official newspaper of the Holy See, wrote that “modern Zionism is not the true heir to the Israel of the Bible, but a secular state…. Therefore the Holy Land and its sacred places belong to Christianity, which is the true Israel.” The Vatican would scrupulously avoid recognition of Israel and even any use of the name for decades after Israel's establishment.[3]

The Vatican's position in 1947 culminated in the incorporation of the corpus separatum status for Jerusalem in the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine and is believed to have influenced Catholic countries, especially in Latin America, to vote in favour of the partition plan. In 1948, this proposal was repeated in UN General Assembly Resolution 194, which again called for Jerusalem to be an international city,[4] under United Nations supervision. Pius XII repeated his support for internationalisation in the 1949 encyclical Redemptoris nostri cruciatus.[citation needed]

The call for internationalisation was repeated by Pope John XXIII. In December 1967, after the Six Day War, Pope Paul VI changed the Vatican's position, now calling for a “special statute, internationally guaranteed” for Jerusalem and the holy places, rather than internationalisation,[3] while still not making any reference to Israel, and the revised position of “international guarantees“ was followed by John Paul II and Benedict XVI.[5] The Vatican reiterated this position in 2012, recognizing Jerusalem's "identity and sacred character" and calling for freedom of access to the city's holy places to be protected by "an internationally guaranteed special statute". After the US recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017, Pope Francis expressed the Vatican's position: "I wish to make a heartfelt appeal to ensure that everyone is committed to respecting the status quo of the city, in accordance with the relevant resolutions of the United Nations."[6]

The corpus separatum in Resolutions 181 and 194

Because of its many holy places and its association with three world religions, Jerusalem had international importance. The United Nations wanted to preserve this status after the termination of the British Mandate and guarantee its accessibility. Therefore, the General Assembly proposed a corpus separatum, as described in Resolution 181.[7] It was to be "under a special international regime and shall be administered by the United Nations". The administering body would be the United Nations Trusteeship Council, one of the five UN "Charter" organs. (See Resolution 181, Part III (A).)

Resolution 181 (II) stated that the corpus separatum would be administered by a Governor appointed by the Trusteeship Council, in accordance to a Statute drafted by the same body. The Statute would then be re-examined by the same Council, allowing for citizens to participate in the process through a referendum.[8]

The corpus separatum covered a rather wide area. The Arabs actually wanted to restore the former status as an open city under Arab sovereignty, but eventually supported the corpus separatum.[9] Israel rejected the plan and supported merely a limited international regime.[10][11] In May 1948, Israel told the Security Council that it regarded Jerusalem outside its territory,[12] but now it claimed sovereignty over Jerusalem except the Holy Places.[citation needed]

Resolution 181

Corpus separatum was initially proposed in UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II) of 29 November 1947, commonly referred to as the UN Partition Plan. It provided that:

"Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem ... shall come into existence in Palestine two months after the evacuation of the armed forces of the mandatory Power has been completed but in any case not later than 1 October 1948".

All the residents would automatically become "citizens of the City of Jerusalem", unless they would opt for citizenship of the Arab or Jewish State.[citation needed]

Failure of the plan

The Partition Plan was not implemented on the ground. The British did not take any measures to establish the international regime and left Jerusalem on 14 May, leaving a power vacuum,[13] as the neighboring Arab nations invaded the newly declared State of Israel.[citation needed]

The Battle for Jerusalem ended on 18 July 1948 with Israel in control of West Jerusalem and Transjordan controlling East Jerusalem. On 2 August 1948 the government of Israel declared West Jerusalem an administered area of Israel.[14][better source needed]

Resolution 194

With the failure to implement the Partition Plan, including the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 194 on 11 December 1948 to establish a UN Conciliation Commission, whose tasks included the implementation of the international regime for the Jerusalem area. Resolution 194 provided the following directives in articles 7, 8, and 9:

- Principle of United Nations supervision

- Resolves that the Holy Places ... in Palestine should be protected and free access to them assured,...; that arrangements to this end should be under effective United Nations supervision; ... in presenting ... its detailed proposals for a permanent international regime for the territory of Jerusalem, should include recommendations concerning the Holy Places in that territory ...

- Area and sovereignty

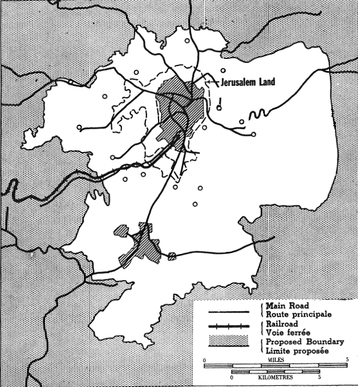

- Resolves that, in view of its association with three world religions, the Jerusalem area, including the present municipality of Jerusalem plus the surrounding villages and towns, the most Eastern of which shall be Abu Dis; the most Southern, Bethlehem; the most Western, Ein Karim (including also the built-up area of Motsa); and the most Northern, Shu'fat, should be accorded special and separate treatment from the rest of Palestine and should be placed under effective United Nations control.[15]

- Demilitarization

- Requests the Security Council to take further steps to ensure the demilitarization of Jerusalem at the earliest possible date.

- Separate control

- Instructs the Conciliation Commission to present to the fourth regular session of the General Assembly detailed proposals for a permanent international regime for the Jerusalem area which will provide for the maximum local autonomy for distinctive groups consistent with the special international status of the Jerusalem area.

- United Nations coordinator

- The Conciliation Commission is authorized to appoint a United Nations representative who shall cooperate with the local authorities with respect to the interim administration of the Jerusalem area.

- Access

- Resolves that, pending agreement on more detailed arrangements among the Governments and authorities concerned, the freest possible access to Jerusalem by road, rail or air should be accorded to all inhabitants of Palestine.

- Attempts to impede right of access

- Instructs the Conciliation Commission to report immediately to the Security Council, for appropriate action by that organ, any attempt by any party to impede such access.

Further developments

At the end of the 1948–49 war, under the Armistice Agreement, an Armistice Demarcation Line was drawn, with West Jerusalem occupied by Israel and the whole West Bank and East Jerusalem, occupied by Transjordan. In the letter of 31 May 1949, Israel told the UN Committee on Jerusalem that it considered another attempt to implement a united Jerusalem under international regime "impracticable" and favored an alternative UN scenario in which Jerusalem would be divided into Jewish and Arab zones.[10]

On 27 August 1949, the Committee on Jerusalem, a subcommittee of the Lausanne Conference of 1949, presented the draft text of a plan for implementation of the international regime. The plan envisioned a demilitarised Jerusalem divided into a Jewish and an Arab zone, without affecting the nationality of its residents. The commentary noted that the committee had abandoned the original principle of a corpus separatum. Jerusalem would be the capital of neither Israel nor the Arab state.[16] On 1 September 1949, the Conciliation Commission, chaired by the United States of America, submitted the plan to the General Assembly.[17] The General Assembly did not accept the plan and it was not discussed.[8]

On 5 December 1949, Israeli Prime Minister Ben-Gurion declared Jewish Jerusalem (i.e. West Jerusalem) an organic, inseparable part of the State of Israel.[18] He also declared Israel no longer bound by Resolution 181 and the corpus separatum null and void, on grounds that the UN had not made good on its guarantees of security for the people of Jerusalem under that agreement.[18] Four days later, on 9 December 1949, the General Assembly approved Resolution 303 which reaffirmed its intention to place Jerusalem under a permanent international regime as a corpus separatum in accordance with the 1947 UN Partition Plan. The resolution requested the Trusteeship Council to complete the preparation of the Statute of Jerusalem without delay.[19] On 4 April 1950, the Trusteeship Council approved a draft statute for the City of Jerusalem, which was submitted to the General Assembly on 14 June 1950.[20] The statute conformed to the partition plan of 29 November 1947. It could not, however, be implemented.[citation needed]

International support

The UN has never revoked resolutions 181 and 194, which continues to be the official position that Jerusalem should be placed under a special international regime.[21] Nevertheless, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said on 28 October 2009 that he personally believed that Jerusalem must be the capital of both Israel and Palestine.[22]

European Union

The European Union continues to support the internationalisation of Jerusalem in accordance with the 1947 UN Partition Plan and regards Jerusalem as having the status of corpus separatum.[23]

United States

The United States did not officially relinquish its early support of the corpus separatum principle until 2017, when it recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. On 23 October 1995, the Congress passed the advisory Jerusalem Embassy Act saying that "Jerusalem should be recognized as the capital of the State of Israel; and the United States Embassy in Israel should be established in Jerusalem no later than May 31, 1999"; nevertheless, the Act contained a provision allowing the President to suspend the motion. Indeed, from 1998 to 2017, the congressional suggestion to relocate the embassy from Tel Aviv was suspended semi-annually by every sitting president, each time noting its necessity "to protect the national security interests of the United States".

During his first presidential campaign, Donald Trump announced that he would move the US embassy to Jerusalem. As president, he said in an interview in February 2017 to the Israeli newspaper Israel Hayom that he was studying the issue.[24] While Trump decided in May not to move the embassy to Jerusalem "for now," to avoid provoking the Palestinians,[25] on 6 December 2017 he recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and has begun the process of moving the embassy to the city. Guatemala followed the United States in moving its consulate to Jerusalem.[26]

Since the Congress does not control U.S. foreign policy, despite the Embassy Act, official U.S. documents and websites did not refer to Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.[27] However, this changed with the recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital by Donald Trump.[28]

Holy See

The Holy See has previously expressed support for the status of corpus separatum.[citation needed] Pope Pius XII was among the first to support such a proposal in the 1949 encyclical Redemptoris nostri cruciatus, and the concept was later re-proposed during the papacies of John XXIII, Paul VI and John Paul II.

Consulates in Jerusalem

Various countries maintain consulates-general in Jerusalem. These operate in a unique way, at great variance with the normal diplomatic practice. The countries which maintain these consulates do not regard them as diplomatic missions to Israel or the Palestinian Authority, but as diplomatic missions to Jerusalem. Where these countries also have embassies to Israel, usually located in Tel Aviv, the Jerusalem-based consul is not subordinate to the ambassador in Tel Aviv (as would be the normal diplomatic usage) but reports directly to the country's foreign ministry. This unique diplomatic situation could be considered, to some degree, as reflecting the corpus separatum which never came into existence.[citation needed]

Status after 1967

Following the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel gained military control of all Jordanian territory west of the Jordan.[29] On 27 June 1967, it extended its law and jurisdiction to 17,600 acres of formerly Jordanian territory, including all of Jordanian Jerusalem and a portion of the nearby West Bank; the area is now known as East Jerusalem, and widely referred to as occupied Jerusalem. The extension was widely regarded as tantamount to annexation and had widely not been recognized internationally. The present municipal boundaries of Jerusalem are not the same as those of the corpus separatum set out in the Partition Plan and do not include, for example, Bethlehem, Motza, or Abu Dis.[citation needed]

In 1980, the Israeli Knesset passed a Jerusalem Law declaring united Jerusalem to be Israel's capital, although the clause "the integrity and unity of greater Jerusalem (Yerushalayim rabati) in its boundaries after the Six-Day War shall not be violated" was dropped from the original bill. United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 of 20 August 1980 condemned this and no countries located their embassies in Jerusalem,[30] until the United States moved its embassy from Tel Aviv in 2018.

In numerous resolutions, the UN has declared every action changing the status of Jerusalem illegal and therefore null and void and having no validity. A recent such resolution was Resolution 66/18 of 30 November 2011.[21]

See also

- Positions on Jerusalem

- UN General Assembly Resolution 194, (1948)

- United Nations Conciliation Commission, (1949)

- Free City of Danzig

References

- ^ UNGA, 29 November 2012 Resolution 67/19. Status of Palestine in the United Nations (doc.nr. A/RES/67/19 d.d. 04-12-2012)

- ^ European Parliament, 5 July 2012, Resolution 2012/2694(RSP) Archived 2014-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b The State of Israel & the Universal Church, Seeking a Theology of the Holy Land, by Massimo Faggioli, May 3, 2018.

- ^ Kane, Gregory (November 28, 2007). "Hearing the Sounds of Silence at Middle East Conference". Virginia Gazette. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20.

- ^ "Vatican Hails UN Palestine Vote, Wants Guarantees for Jerusalem". Haaretz.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (6 December 2017). "U.N., European Union and Pope Criticize Trump's Jerusalem Announcement". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (II)" (PDF). United Nations. p. 146 (pdf p.16).

- ^ a b CEIRPP/DPR, 1 January 1981, The status of Jerusalem, see chapter VI. Accessed 10 Dec 2023. Also here (original) Archived December 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ UN Committee on Jerusalem, Meeting between the Committee on Jerusalem and the delegations of the Arab states, 20 June 1949 (doc.nr. A/AC.25/Com.Jer./SR.33)

- ^ a b Letter dated 31 May 1949, addressed by Mr. Walter Eytan, Head of the Delegation of Israel (doc.nr. A/AC.25/Com.Jer/9 d.d. 01-06-1949)

- ^ UNCCP, 5 April 1949, second progress report Archived June 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (doc.nr. A/838 d.d.19-04-1949), see par. 28.

- ^ UNGA, 22 May 1948, Replies of Provisional Government of Israel to Security Council questionnaire Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (doc.nr. S/766)

- ^ Yoav Gelber, Independence Versus Nakba; Kinneret–Zmora-Bitan–Dvir Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-965-517-190-7, p.104

- ^ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 12 August 1948, 2 Jerusalem Declared Israel-Occupied City- Government Proclamation (onweb.archive.org/)

- ^ This area equals that of Resolution 181, Part III (B).

- ^ UN Committee on Jerusalem, 27 August 1949, Third progress report to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (doc.nr. A/AC.25/Com.Jer/12)

- ^ UNCCP, 1 September 1949 Palestine – Proposals for a permanent international regime for the Jerusalem area (doc.nr. A/973 d.d. 12-09-1949). The plan was explained in document A/973/Add.1 (12-11-1949).

- ^ a b Knesset website, Statements of the Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion Regarding Moving the Capital of Israel to Jerusalem. Retrieved 13-05-2013

- ^ UNGA, 9 December 1949, Resolution 303 (IV). Palestine: Question of an international regime for the Jerusalem area and the protection of the Holy Places Archived October 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine [doc.nr. A/RES/303 (IV)]

- ^ UNGA, 14 June 1950, General Assembly official records: Fifth session supplement no. 9 (A/1286) Archived November 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Question of an international regime for the Jerusalem area and protection of the Holy Places – Special Report of the Trusteeship Council (see Annex II)

- ^ a b UNGA, 30 November 2011, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 66/18. Jerusalem Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine (doc.nr. A/RES/66/18 d.d. 26-01-2012)

"Recalling its resolution 181 (II) of 29 November 1947, in particular its provisions regarding the City of Jerusalem,"

"Reiterates its determination that any actions taken by Israel, the occupying Power, to impose its laws, jurisdiction and administration on the Holy City of Jerusalem are illegal and therefore null and void and have no validity whatsoever," - ^ Jerusalem must be capital of both Israel and Palestine, Ban says, UN News Centre, (October 28, 2009)

- ^ Foundation for Middle East Peace – May 1999: "Europe Affirms Support for a Corpus Separatum for Greater Jerusalem"

- ^ Paton, Callum (May 3, 2017). "Trump 'Seriously Considering' Moving U.S. Embassy To Jerusalem: Pence". Newsweek. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (May 17, 2017). "Donald Trump abandons plan to move Israel embassy to Jerusalem". The Independent. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ "Guatemala opens embassy in Jerusalem, two days after U.S. move". Reuters. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ Adam Kredo, Solving the White House photo mystery over ‘Jerusalem, Israel’. JTA, 16 August 2011

- ^ "Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem". Federal Register. 2017-12-11. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ Dumper, The politics of Jerusalem since 1967, Page 42: "Despite full military control and the assertion of total Israeli sovereignty over the whole of Jerusalem"

- ^ Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Resident Missions – Heads of Missions and Addresses. 2016. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-23. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)