Eurovision Song Contest 1994

| Eurovision Song Contest 1994 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dates | |

| Final | 30 April 1994 |

| Host | |

| Venue | Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland |

| Presenter(s) | Cynthia Ní Mhurchú Gerry Ryan |

| Executive producer | Moya Doherty |

| Director | Patrick Cowap |

| Musical director | Noel Kelehan |

| EBU scrutineer | Christian Clausen |

| Host broadcaster | Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ) |

| Website | eurovision |

| Participants | |

| Number of entries | 25 |

| Debuting countries | |

| Returning countries | None |

| Non-returning countries | |

| |

| Vote | |

| Voting system | Each country awarded 12, 10, 8-1 point(s) to their 10 favourite songs |

| Winning song | "Rock 'n' Roll Kids" |

The Eurovision Song Contest 1994 was the 39th edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, held on 30 April 1994 at the Point Theatre in Dublin, Ireland. Organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and host broadcaster Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ), and presented by Cynthia Ní Mhurchú and Gerry Ryan, the contest was held in Ireland following the country's victory at the 1993 contest with the song "In Your Eyes" by Niamh Kavanagh. It was the first time that any country had hosted two successive editions of the contest, following the previous year's contest held in Millstreet.

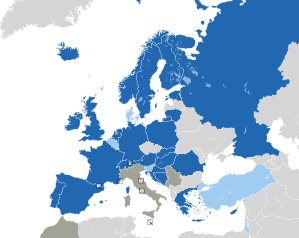

Twenty-five countries participated in the contest, which for the first time featured a relegation system to reduce the number of interested participating countries. Seven new countries participated in the event, with entries from Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia and Slovakia featuring for the first time. However, Belgium, Denmark, Israel, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey were unable to compete due to the new relegation rules as the lowest-scoring countries at the previous event, whereas Italy decided against participating by choice.

For the third time in a row, Ireland won the contest with the song "Rock 'n' Roll Kids", written by Brendan Graham and performed by Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan. Never before had a country won three times in a row in the history of the contest; at the same time, it was also a record sixth win, cementing Ireland as the country with the most wins in Eurovision history up till that point. Poland, Germany, Hungary and Malta rounded out the top five positions, with Poland achieving the most successful result for a début entry in the contest's history.

The 1994 contest also featured the first appearance of Riverdance. Originally a seven-minute performance of traditional Irish and modern music, choral singing and Irish dancing featured as part of the contest's interval act, it was subsequently developed into a full stage show which has since become a worldwide phenomenon and catapulted the careers of its lead dancers Jean Butler and Michael Flatley.

Location

[edit]

The 1994 contest took place in Dublin, Ireland, following the country's victory at the 1993 edition with the song "In Your Eyes", performed by Niamh Kavanagh. It was the fifth time that Ireland had hosted the contest, following the 1971, 1981 and 1988 events also held in Dublin, and the previous year's event held in Millstreet.[1] Ireland thus became the first country to host two successive contests.[2][3]

The selected venue was the Point Theatre, a concert and events venue located among the Dublin Docklands and originally built as a train depot and warehouse to serve the nearby port. Opened as a music venue in 1988, it was closed for redevelopment and expansion in 2008 and is now known as the 3Arena.[3][4] At the time of the contest, the arena could seat around 3,200 audience members.[3]

Participating countries

[edit]| Eurovision Song Contest 1994 – Participation summaries by country | |

|---|---|

Twenty-five countries were permitted to participate in the contest. As the number of countries interested in participating in the contest grew, and following the use of a qualifying round in the previous year's event, a relegation system was introduced to the contest for the first time, which would prevent the lowest-scoring countries from the previous year's event from participating in the subsequent contest.[3][5] In the summer of 1993 the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) confirmed that the seven lowest-scoring countries in the 1993 event would be barred from entering the 1994 contest, to make way for seven countries which would participate for the first time.[3] As a result, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Israel, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Turkey were unable to enter the contest, and in the contest's largest single expansion of new participating countries since the first edition in 1956, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, and Slovakia made their début appearances.[3][5][6] Estonia, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia had all previously participated in the 1993 qualifying round Kvalifikacija za Millstreet.[7] Belgium thus failed to participate in the contest for the first time, leaving Germany and Switzerland as the only countries to have competed in every edition of the contest so far.[3] Later in 1993 Italy's broadcaster RAI subsequently announced that it would not participate in the event, likely due to a lack of interest in the event among the Italian public and concerns within the broadcaster at the costs of staging the contest in the event that Italy won;[8][9] this led to Cyprus being readmitted as the relegated country with the best result at the 1993 contest.[3]

Four performers who had competed in previous editions of contests featured among the participating artists at this year's event: Marie Bergman, representing Sweden with Roger Pontare, had been a member of the group Family Four that had represented the country in the 1971 and 1972 contests; Cyprus's Evridiki made a second appearance in the contest, following her entry at the 1992 event; Sigga returned to the contest for Iceland for a third time, having previously competed as part of Stjórnin in 1990 and Heart 2 Heart in 1992; and Elisabeth Andreasson, competing in this event with Jan Werner Danielsen for Norway, also participated for the third time, having been a member of the group Chips, which represented Sweden in 1982, and Bobbysocks!, which had represented Norway and were the winners of the 1985 contest.[10] A number of artists which had previously competed in the contest also returned as backing performers: Rhonda Heath, who was a member of the group Silver Convention that had represented Germany in the 1977 contest, performed as a backing singer for the German entry MeKaDo;[11] and Eyjólfur Kristjánsson, who represented Iceland at the 1991 contest alongside Stefán Hilmarsson, returned as a backing singer for Sigga.[12] Additionally, having supported Malta's William Mangion as backing performers in the previous year's event, Moira Stafrace and Christopher Scicluna returned to the Eurovision stage as the country's entrants at this year's contest.[13]

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) | Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Petra Frey | "Für den Frieden der Welt" | German |

|

Hermann Weindorf | |

| RTVBiH | Alma and Dejan | "Ostani kraj mene" | Bosnian |

|

Sinan Alimanović | |

| HRT | Tony Cetinski | "Nek' ti bude ljubav sva" | Croatian |

|

Miljenko Prohaska | |

| CyBC | Evridiki | "Ime anthropos ki ego" (Είμαι άνθρωπος κι εγώ) | Greek | George Theofanous | George Theofanous | |

| ETV | Silvi Vrait | "Nagu merelaine" | Estonian | Urmas Lattikas | ||

| YLE | CatCat | "Bye Bye Baby" | Finnish |

|

Olli Ahvenlahti | |

| France Télévision | Nina Morato | "Je suis un vrai garçon" | French |

|

Alain Goraguer | |

| MDR[a] | Mekado | "Wir geben 'ne Party" | German | Norbert Daum | ||

| ERT | Kostas Bigalis and the Sea Lovers | "To trehandiri (Diri Diri)" (Το τρεχαντήρι (Ντίρι Ντίρι)) | Greek | Kostas Bigalis | Noel Kelehan | |

| MTV | Friderika | "Kinek mondjam el vétkeimet?" | Hungarian | Szilveszter Jenei | Péter Wolf | |

| RÚV | Sigga | "Nætur" | Icelandic | Frank McNamara | ||

| RTÉ | Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan | "Rock 'n' Roll Kids" | English | Brendan Graham | No conductor | |

| LRT | Ovidijus Vyšniauskas | "Lopšinė mylimai" | Lithuanian |

|

Tomas Leiburas | |

| PBS | Moira Stafrace and Christopher Scicluna | "More than Love" | English | Anthony Chircop | ||

| NOS | Willeke Alberti | "Waar is de zon" | Dutch |

|

Harry van Hoof | |

| NRK | Elisabeth Andreasson and Jan Werner Danielsen | "Duett" | Norwegian |

|

Pete Knutsen | |

| TVP | Edyta Górniak | "To nie ja!" | Polish |

|

Noel Kelehan | |

| RTP | Sara | "Chamar a música" | Portuguese |

|

Thilo Krasmann | |

| TVR | Dan Bittman | "Dincolo de nori" | Romanian |

|

Noel Kelehan | |

| RTR | Youddiph | "Vechny strannik"[b] (Вечный странник) | Russian |

|

Lev Zemlinski | |

| STV | Martin Ďurinda and Tublatanka | "Nekonečná pieseň" | Slovak | Vladimír Valovič | ||

| TVE | Alejandro Abad | "Ella no es ella" | Spanish | Alejandro Abad | Josep Llobell | |

| SVT | Marie Bergman and Roger Pontare | "Stjärnorna" | Swedish |

|

Anders Berglund | |

| SRG SSR | Duilio | "Sto pregando" | Italian | Giuseppe Scaramella | Valeriano Chiaravalle | |

| BBC | Frances Ruffelle | "We Will Be Free (Lonely Symphony)" | English |

|

Michael Reed |

Production and format

[edit]The Eurovision Song Contest 1994 was produced by the Irish public broadcaster Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ). Moya Doherty served as executive producer, Patrick Cowap served as director, Paula Farrell served as designer, and Noel Kelehan served as musical director, leading the RTÉ Concert Orchestra.[6][16][17] A separate musical director could be nominated by each country to lead the orchestra during their performance, with the host musical director also available to conduct for those countries which did not nominate their own conductor.[10] On behalf of the contest organisers, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the event was overseen by Christian Clausen as scrutineer.[6][18][19]

Each participating broadcaster submitted one song, which was required to be no longer than three minutes in duration and performed in the language, or one of the languages, of the country which it represented.[20][21] A maximum of six performers were allowed on stage during each country's performance, and all participants were required to have reached the age of 16 in the year of the contest.[20][22] Each entry could utilise all or part of the live orchestra and could use instrumental-only backing tracks; however, any backing tracks used could only include the sound of instruments featured on stage being mimed by the performers.[22][23]

Following the confirmation of the twenty-five competing countries, the draw to determine the running order was held on 16 November 1993 at the Point Theatre and was conducted by Niamh Kavanagh and Fionnuala Sweeney.[3][24][25]

The results of the 1994 contest were determined through the same scoring system as had first been introduced in 1975: each country awarded twelve points to its favourite entry, followed by ten points to its second favourite, and then awarded points in decreasing value from eight to one for the remaining songs which featured in the country's top ten, with countries unable to vote for their own entry.[26] The points awarded by each country were determined by an assembled jury of sixteen individuals, which was required to be split evenly between members of the public and music professionals, between men and women, and by age. Each jury member voted in secret and awarded between one and ten votes to each participating song, excluding that from their own country and with no abstentions permitted. The votes of each member were collected following the country's performance and then tallied by the non-voting jury chairperson to determine the points to be awarded. In any cases where two or more songs in the top ten received the same number of votes, a show of hands by all jury members was used to determine the final placing.[27][28]

With the Point Theatre situated on the banks of the River Liffey, rivers were an integral part of the overall creative vision for the show and were a key theme of the opening and interval acts as well as the stage design.[29] Paula Farrell's design, which was four times the size of the stage constructed for the Millstreet contest, provided a scene of a futuristic Dublin at night, featuring representations of skyscrapers which incorporated video screens and lighting effects and underfloor lighting representing the Liffey and Dublin Bay. On either side of the stage podium-lined platforms were used by the presenters in-between songs and during the voting segment.[30][31][32][33]

Rehearsals at the contest venue began on 25 April 1994. Each participating delegation took part in two technical rehearsals in the week approaching the contest, with countries rehearsing in the order in which they would perform. In each country's first rehearsal, held on 25 and 26 April, the delegations were provided with a 15-minute stage-call to prepare the stage and to brief the orchestra, followed by a 25-minute rehearsal. This was then followed by an opportunity to review footage of the rehearsal on video screens and to conduct a 20-minute press conference. The second rehearsals on 27 and 28 April consisted of a 10-minute stage-call and a 20-minute rehearsal. Three dress rehearsals were held with all artists, two in the afternoon and evening of 29 April and one final rehearsal in the afternoon of 30 April, with an audience present at the evening rehearsal on 29 April. The competing delegations were additionally invited to a welcome reception during the week of the event, held on the evening of 25 April in the Dining Hall of Trinity College Dublin.[3]

During the final dress rehearsal on 30 April, the Polish entrant Edyta Górniak performed the second half of her song "To nie ja!" in English. As this rehearsal was also heard by the juries this constituted a break of the contest rules. Although discussions were held on whether to sanction or disqualify the country, Poland was ultimately allowed to compete.[6][10][30]

Contest overview

[edit]

The contest took place on 30 April 1994 at 20:00 (IST) and lasted 3 hours and 3 minutes. The show was presented by the Irish journalist and television presenter Cynthia Ní Mhurchú and the Irish radio and television presenter Gerry Ryan.[6][10] Ní Mhurchú and Ryan had been considered as hosts for the 1993 event before the eventual choice of Fionnuala Sweeney.[34]

The contest was opened with a segment by the Galway-based arts and theatre company Macnas, featuring a mixture of pre-recorded and live footage of a replica Viking longship on the river Liffey, and dancers, flag-bearers and performers in caricature masks of notable Irish personalities in various locations in central Dublin and in the Point Theatre.[3][35][36][37] The interval act, "Riverdance", was a seven-minute composition by the Irish composer Bill Whelan, and took inspiration from "Timedance", the interval act from the 1981 contest also held in Dublin.[38] "Riverdance" featured a mix of traditional Irish and modern music by the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, choral singing from the Celtic ensemble Anúna, and Irish dancing led by the Irish-American dancers Jean Butler and Michael Flatley.[39][40] The trophy awarded to the winners, entitled "Wavelength", was designed by the Irish sculptor Grace Weir of the Temple Bar Gallery, and was presented by the previous year's winning artist Niamh Kavanagh.[35][41][42]

The winner was Ireland represented by the song "Rock 'n' Roll Kids", written by Brendan Graham and performed by Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan.[43] This marked Ireland's sixth contest win – a new contest record – and also gave the country its third win in a row – the first time a country had won three successive contests.[1][5][27] "Rock 'n' Roll Kids" became the highest scoring winner in Eurovision history to date with 226 points, and was the first song to receive over 200 points. It was also the first time that a song had won without using the orchestra. Harrington and McGettigan additionally became the oldest winning performers and the first winning male duo.[5][27][30] First-time participating countries Poland, Hungary and Russia all finished in the top ten, placing second, fourth and ninth respectively, while conversely the four other débuting countries all placed within the bottom seven entries, with Lithuania scoring nul points with its first ever entry.[44][45] Poland achieved the most successful début performance of any country in the contest's history at the time, and its second-place finish in this event remains as of 2024[update] the country's best ever Eurovision placing.[2][46]

| R/O | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marie Bergman and Roger Pontare | "Stjärnorna" | 48 | 13 | |

| 2 | CatCat | "Bye Bye Baby" | 11 | 22 | |

| 3 | Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan | "Rock 'n' Roll Kids" | 226 | 1 | |

| 4 | Evridiki | "Ime anthropos ki ego" | 51 | 11 | |

| 5 | Sigga | "Nætur" | 49 | 12 | |

| 6 | Frances Ruffelle | "We Will Be Free (Lonely Symphony)" | 63 | 10 | |

| 7 | Tony Cetinski | "Nek' ti bude ljubav sva" | 27 | 16 | |

| 8 | Sara | "Chamar a música" | 73 | 8 | |

| 9 | Duilio | "Sto pregando" | 15 | 19 | |

| 10 | Silvi Vrait | "Nagu merelaine" | 2 | 24 | |

| 11 | Dan Bittman | "Dincolo de nori" | 14 | 21 | |

| 12 | Moira Stafrace and Christopher Scicluna | "More than Love" | 97 | 5 | |

| 13 | Willeke Alberti | "Waar is de zon" | 4 | 23 | |

| 14 | Mekado | "Wir geben 'ne Party" | 128 | 3 | |

| 15 | Martin Ďurinda and Tublatanka | "Nekonečná pieseň" | 15 | 19 | |

| 16 | Ovidijus Vyšniauskas | "Lopšinė mylimai" | 0 | 25 | |

| 17 | Elisabeth Andreasson and Jan Werner Danielsen | "Duett" | 76 | 6 | |

| 18 | Alma and Dejan | "Ostani kraj mene" | 39 | 15 | |

| 19 | Kostas Bigalis and the Sea Lovers | "To trehandiri (Diri Diri)" | 44 | 14 | |

| 20 | Petra Frey | "Für den Frieden der Welt" | 19 | 17 | |

| 21 | Alejandro Abad | "Ella no es ella" | 17 | 18 | |

| 22 | Friderika | "Kinek mondjam el vétkeimet?" | 122 | 4 | |

| 23 | Youddiph | "Vechny strannik"[b] | 70 | 9 | |

| 24 | Edyta Górniak | "To nie ja!" | 166 | 2 | |

| 25 | Nina Morato | "Je suis un vrai garçon" | 74 | 7 |

Spokespersons

[edit]Each country nominated a spokesperson who was responsible for announcing, in English or French, the votes for their respective country.[20] For the first time, the spokespersons were connected to the venue via satellite rather than through telephone lines, allowing them to appear in vision during the broadcast.[2][6][27] Spokespersons at the 1994 contest are listed below.[35]

Sweden – Marianne Anderberg[47]

Sweden – Marianne Anderberg[47] Finland – Solveig Herlin

Finland – Solveig Herlin Ireland – Eileen Dunne[48]

Ireland – Eileen Dunne[48] Cyprus – Anna Partelidou

Cyprus – Anna Partelidou Iceland – Sigríður Arnardóttir

Iceland – Sigríður Arnardóttir United Kingdom – Colin Berry[27]

United Kingdom – Colin Berry[27] Croatia – Helga Vlahović[49]

Croatia – Helga Vlahović[49] Portugal – Isabel Bahia

Portugal – Isabel Bahia Switzerland – Sandra Studer

Switzerland – Sandra Studer Estonia – Urve Tiidus[50]

Estonia – Urve Tiidus[50] Romania – Cristina Țopescu

Romania – Cristina Țopescu Malta – John Demanuele[51]

Malta – John Demanuele[51] Netherlands – Joop van Os[52]

Netherlands – Joop van Os[52] Germany – Carmen Nebel

Germany – Carmen Nebel Slovakia – Juraj Čurný

Slovakia – Juraj Čurný Lithuania – Gitana Lapinskaitė[53]

Lithuania – Gitana Lapinskaitė[53] Norway – Sverre Christophersen

Norway – Sverre Christophersen Bosnia and Herzegovina – Diana Grković-Foretić

Bosnia and Herzegovina – Diana Grković-Foretić Greece – Fotini Giannoulatou

Greece – Fotini Giannoulatou Austria – Tilia Herold

Austria – Tilia Herold Spain – María Ángeles Balañac

Spain – María Ángeles Balañac Hungary – Iván Bradányi

Hungary – Iván Bradányi Russia – Irina Klenskaya

Russia – Irina Klenskaya Poland – Jan Chojnacki

Poland – Jan Chojnacki France – Laurent Romejko[54]

France – Laurent Romejko[54]

Detailed voting results

[edit]Jury voting was used to determine the points awarded by all countries.[27] The announcement of the results from each country was conducted in the order in which they performed, with the spokespersons announcing their country's points in English or French in ascending order.[27][35] The detailed breakdown of the points awarded by each country is listed in the tables below.

Total score

|

Sweden

|

Finland

|

Ireland

|

Cyprus

|

Iceland

|

United Kingdom

|

Croatia

|

Portugal

|

Switzerland

|

Estonia

|

Romania

|

Malta

|

Netherlands

|

Germany

|

Slovakia

|

Lithuania

|

Norway

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

Greece

|

Austria

|

Spain

|

Hungary

|

Russia

|

Poland

|

France

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contestants

|

Sweden | 48 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Finland | 11 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 226 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 8 | |||

| Cyprus | 51 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Iceland | 49 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 63 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Croatia | 27 | 10 | 12 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 73 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 15 | 8 | 2 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Estonia | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romania | 14 | 6 | 2 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malta | 97 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Netherlands | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 128 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 12 | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| Slovakia | 15 | 12 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lithuania | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 76 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 8 | |||||||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 39 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Greece | 44 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Austria | 19 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 17 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hungary | 122 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 7 | ||||||||

| Russia | 70 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 1 | |||||||||

| Poland | 166 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 12 | |||||

| France | 74 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 6 | |||||||||||||

12 points

[edit]The below table summarises how the maximum 12 points were awarded from one country to another. The winning country is shown in bold. Ireland received the maximum score of 12 points from eight of the voting countries, with Poland receiving five sets of 12 points, Hungary receiving four sets, Germany two sets, and Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Portugal and Slovakia each receiving one maximum score.[55][56]

| N. | Contestant | Nation(s) giving 12 points |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 1 | ||

Broadcasts

[edit]Each participating broadcaster was required to relay the contest via its networks. Non-participating EBU member broadcasters were also able to relay the contest as "passive participants".[22] Broadcasters were able to send commentators to provide coverage of the contest in their own native language and to relay information about the artists and songs to their television viewers. These commentators were typically sent to the venue to report on the event, and were able to provide commentary from small booths constructed at the back of the venue.[57][58] Known details on the broadcasts in each country, including the specific broadcasting stations and commentators are shown in the tables below.

| Country | Broadcaster | Channel(s) | Commentator(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | SBS TV[d] | [93] | ||

| BRTN | TV2 | André Vermeulen | [94] | |

| Radio 2 | Marc Brillouet and Julien Put | [95] | ||

| RTBF | RTBF1 | Jean-Pierre Hautier | [96] | |

| DR | DR TV | Jørgen de Mylius | [97] | |

| SvF | [98] | |||

| KNR | KNR[e] | [99] | ||

| IBA | Channel 1 | [100] | ||

| JRTV | JTV2 | [101] | ||

| RTVSLO | SLO 1 | Damjana Golavšek | [102] | |

| Val 202 | [103] | |||

| KBS | KBS2[f] | [104] | ||

| TRT | TRT 1 | [105] | ||

| RTS | RTS 3K | [106] | ||

Legacy

[edit]

Although the winning song had modest success, peaking in the Irish Singles Chart at number 2 and also entering the Dutch and Flemish charts following the contest,[107][108] it was largely overshadowed by the contest's interval act. The music to "Riverdance" was subsequently released as a single shortly after the contest and shot straight to number 1 on the Irish charts where it remained for 18 weeks.[109][110] As of 2023[update] "Riverdance" remains the second best selling single in Ireland ever, behind Elton John's "Something About the Way You Look Tonight"/"Candle in the Wind 1997".[110][111] An invite was subsequently given to feature the original seven-minute performance at the Royal Variety Performance in November 1994 at the Dominion Theatre in London in the presence of Prince Charles.[112] At the same time preparations were underway to develop the seven-minute performance into a stage show, preparations led by Moya Doherty, who had been the executive producer of Eurovision 1994, and her husband John McColgan.[113][114] Opening in February 1995 at the Point Theatre and featuring original lead dancers Michael Flatley and Jean Butler, the full-length show ran for an initial run of five weeks, with tickets selling out within three days of going on sale, followed by another sold-out run at the Hammersmith Apollo in London and in March 1996 its first performance in the United States, at the Radio City Music Hall in New York City.[110][115][116] It is estimated that Riverdance has now been seen live by over 27.5 million people at performances worldwide, and that over 10 million home videos of Riverdance performances have been sold.[113]

The relegation system introduced to the contest in this edition continued to be used in various forms for the next ten years and allowed even more new countries to join the event, with Macedonia, Latvia and Ukraine competing for the first time in 1998, 2000 and 2003 respectively.[117][118][119] However, as the contest continued to develop, and as even more countries began to express an interest in competing, the relegation system proved unable to meet the needs required to allow for an equitable solution for all countries. Ultimately this led to the introduction of a semi-final to the contest format in 2004, allowing all interested countries to participate once again, which was eventually expanded to two semi-finals from 2008.[5][120][121]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ On behalf of the German public broadcasting consortium ARD[15]

- ^ a b On-screen captions used the English title "Eternal Wanderer"

- ^ Additional live broadcast on BBC World Service Television[75]

- ^ Deferred broadcast the following day at 20:30 (AEST)[93]

- ^ Deferred broadcast at 21:20 (WGST)[99]

- ^ Delayed broadcast on 28 May 1994 at 15:15 (KST)[104]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Ireland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "18 years ago today - Ireland makes it three in a row". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Roxburgh 2020, pp. 168–170.

- ^ "3Arena Dublin – About, History & Hotels Near". O'Callaghan Collection. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Jordan, Paul (18 September 2016). "Milestone Moments: 1993/4 - The Eurovision Family expands". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Dublin 1994". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Roxburgh 2020, pp. 131–135.

- ^ Castagneri, Lorenzo (10 May 2016). "Tutto quello che c'è da sapere sull'Eurovision Song Contest 2016" [Everything you need to know about the Eurovision Song Contest 2016]. La Stampa (in Italian). Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Visentin, Barbara (5 September 2022). "L'Eurovision e l'Italia: tre vittorie, un ultimo posto, polemiche e curiosità" [Eurovision and Italy: three victories, one last place, controversies and curiosities]. Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Roxburgh 2020, pp. 170–178.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (11 May 2017). "Eurovision continues to unite states". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Egan, John (18 October 2017). "Upcycling At The Eurovision Song Contest: How To Get The Most Out Of Your Local Music Industry". ESC Insight. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ Agius, Monique (18 February 2022). "Musician and singer, Chris Scicluna, passes away aged 62". Newsbook Malta. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Dublin 1994 – Participants". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel" [All German ESC acts and their songs] (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Roxburgh 2020, p. 181.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 217.

- ^ "The Organisers behind the Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 210.

- ^ a b c "How it works". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 18 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Jerusalem 1999". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "The Rules of the Contest". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (18 April 2020). "#EurovisionAgain travels back to Dublin 1997". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Harding, Peter (November 1993). The Point Depot, Dublin city (1993) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ Harding, Peter (April 1994). Eurovision Song Contest draw (1993) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ "In a Nutshell". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roxburgh 2020, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Roxburgh 2020, p. 73.

- ^ Kelly, Ben (29 April 2019). "Riverdance at 25: How Eurovision gave birth to an Irish cultural phenomenon". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c O'Connor 2010, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Knox 2015, pp. 141–154, Chapter 16. The Interval Act.

- ^ Harding, Peter (April 1994). Eurovision Song Contest set (1994) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ Harding, Peter (April 1994). Wide shot of Eurovision set (1994) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ Knox 2015, pp. 129–140, Chapter 15. The Cowshed in Cork.

- ^ a b c d Eurovision Song Contest 1994 (Television programme) (in English, French, and Irish). Dublin, Ireland: Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ). 30 April 1994.

- ^ Gaffney, Des (December 1992). Macnas on stage at Eurovision (1994) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ Harding, Peter (December 1992). Macnas perform at Eurovision (1994) (Photograph). Point Theatre, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ "Riverdance: an Irish success story". Claddagh Design. 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Connolly, Colm (30 April 1994). Riverdance Debut at Eurovision in Dublin (News report). Dublin, Ireland: RTÉ News. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ "Riverdance First Performance". Dublin, Ireland: RTÉ. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ Harding, Peter (1994). Eurovision Song Contest trophy (1994) (Photograph). Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- ^ O'Connor 2010, p. 216.

- ^ "Dublin 1994 – Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Dublin 1994 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Poland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Thorsson & Verhage 2006, pp. 242–243.

- ^ O'Loughlin, Mikie (8 June 2021). "RTE Eileen Dunne's marriage to soap star Macdara O'Fatharta, their wedding day and grown up son Cormac". RSVP Live. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Helga Vlahović: 1990 presenter has died". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Eesti žürii punktid edastab Eurovisioonil Tanel Padar" [The points of the Estonian jury at Eurovision will be announced by Tanel Padar] (in Estonian). Muusika Planeet. 14 May 2022. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Malta fifth in Euro contest". Times of Malta. Birkirkara, Malta. 1 May 1994. p. 1.

- ^ Beerekamp, Hans (2 May 1994). "Willeke laat Litouwen en Estland achter zich" [Willeke leaves Lithuania and Estonia behind]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). Amsterdam, Netherlands. p. 23. Retrieved 17 December 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ Juršėnaitė, Eimantė (18 May 2019). "Pirmojoje nacionalinėje "Eurovizijos" atrankoje dalyvavo ir šiandien pažįstami veidai" [The first Eurovision national selection was attended by familiar faces of today] (in Lithuanian). Lithuanian National Radio and Television (LRT). Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ a b "les programmes TV – samedi 30 avril" [TV programmes – Saturday 30 April]. L'Est éclair (in French). Saint-André-les-Vergers, France. 30 April 1994. p. 23. Retrieved 22 September 2024 – via Aube en Champagne.

- ^ a b c "Dublin 1994 – Detailed voting results". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Eurovision Song Contest 1994 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Commentator's guide to the commentators". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 15 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ Escudero, Victor M. (14 May 2017). "Commentators: The national hosts of Eurovision". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d "TV + Radio · Samstag" [TV + Radio · Saturday]. Bieler Tagblatt (in German). Biel, Switzerland. 30 April 1994. p. 22. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via E-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Halbhuber, Axel (22 May 2015). "Ein virtueller Disput der ESC-Kommentatoren" [A virtual dispute between Eurovision commentators]. Kurier (in German). Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Program HRT" [HRT schedule]. Glas Podravine (in Serbo-Croatian). Koprivnica, Croatia. 29 April 1994. p. 9. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Eurosong seli u Belfast kao glazbeni zalog miru?" [Eurovision to move to Belfast as a musical pledge for peace?]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Split, Croatia. 5 May 1994. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Ραδιοτηλεοραση – Σαββατο" [Radio-Television – Saturday]. I Simerini (in Greek). Nicosia, Cyprus. 30 April 1994. p. 6. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024 – via Press and Information Office.

- ^ "Ραδιοφωνο" [Radio]. O Phileleftheros (in Greek). Nicosia, Cyprus. 9 May 1992. p. 22. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024 – via Press and Information Office.

- ^ a b "Televisioon" [Television]. Post (in Estonian). Tallinn, Estonia. 30 April 1994. p. 4. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via DIGAR.

- ^ "Vello Rand: väga raske on ennustada, milline laul Dublinis võidab" [Vello Rand: It's very difficult to predict which song will win in Dublin]. Post (in Estonian). Tallinn, Estonia. 28 April 1994. p. 1. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via DIGAR.

- ^ "Televisio & Radio" [Television & Radio]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland. 30 April 1994. pp. D11 – D12. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "TV szombat | április 30" [Television Saturday | 30 April]. Rádió és TeleVízió újság (in Hungarian). 25 April 1994. pp. 46–47. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022 – via MTVA Archívum.

- ^ "Laugurdagur 30. apríl" [Saturday 30 April]. DV (in Icelandic). Reykjavík, Iceland. 30 April 1994. p. 54. Retrieved 28 May 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "Saturday: Television and Radio". The Irish Times Weekend. Dublin, Ireland. 30 April 1994. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Walsh, Niamh (3 September 2017). "Pat Kenny: 'As Long As People Still Want Me I'll Keep Coming To Work'". evoke.ie. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "TV – sobota, 30 kwietnia" [TV – Saturday, 30 April] (PDF). Kurier Wileński (in Polish). Vilnius, Lithuania. 30 April 1994. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022 – via Polonijna Biblioteka Cyfrowa.

- ^ "Television". Times of Malta. Birkirkara, Malta. 30 April 1994. p. 28.

- ^ "Programma's RTV Zaterdag" [Radio TV programmes on Saturday]. Leidsch Dagblad (in Dutch). Leiden, Netherlands. 30 April 1994. p. 8. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ a b "TV – Lørdag 30. april" [TV – Saturday 30 April]. Moss Dagblad (in Norwegian). Moss, Norway. 30 April 1994. p. 36. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via National Library of Norway.

- ^ "Norgeskanalen P1 – Kjøreplan lørdag 30. april 1994" [The Norwegian channel P1 – Schedule Saturday 30 April 1994] (in Norwegian). NRK. 30 April 1994. p. 17. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via National Library of Norway. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- ^ "Program telewizyjny 29.04–5.05 – Sobota 30.04" [Television schedule 29/04–5/05 – Saturday 30/04]. Pałuki (in Polish). 29 April 1994. p. 11. Retrieved 28 June 2024 – via Kujawsko-Pomorska Digital Library.

- ^ "Artur Orzech – Eurowizja, żona, dzieci, wiek, wzrost, komentarze" [Artur Orzech – Eurovision, wife, children, age, height, comments] (in Polish). Radio Eska. 18 May 2021. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Programa da televisão" [Television schedule]. A Comarca de Arganil (in Portuguese). Arganil, Portugal. 28 April 1994. p. 8. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Firmino, Tiago (7 April 2018). "O número do dia. Quantos festivais comentou Eládio Clímaco na televisão portuguesa?" [Number of the day. How many festivals did Eládio Clímaco comment on on Portuguese television?] (in Portuguese). N-TV. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Panoramic T.V. | Săptămână 29 aprilie – 5 mai 1994" [Panoramic T.V. | Week of 29 April – 5 May 1994] (PDF). Adevărul de Arad (in Romanian). Arad, Romania. 29 April 1994. p. 7. Retrieved 26 October 2024 – via Biblioteca Județeană "Alexandru D. Xenopol" Arad.

- ^ Vacaru, Clara (2 October 2015). "Abia o recunoşti! Cum arăta Gabi Cristea în urmă cu 20 de ani, la debutul în televiziune" [You can barely recognize her! How did Gabi Cristea look 20 years ago when she made her television debut]. Libertatea (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Неделя телевизионного экрана" [Weekly television screen] (PDF). Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian). 22 April 1994. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Лучшие певцы Европы" [The best singers in Europe] (PDF). Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian). 22 April 1994. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Mi? Hol? Mikor? – szombat" [What? Where? When? – Saturday]. Új Szó (in Hungarian). Bratislava, Slovakia. 30 April 1994. p. 8. Retrieved 21 September 2024 – via Hungaricana.

- ^ "Televisión" [Television]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Barcelona, Spain. 30 April 1994. p. 6. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ HerGar, Paula (28 March 2018). "Todos los comentaristas de la historia de España en Eurovisión (y una única mujer en solitario)" [All the commentators in the history of Spain in Eurovision (and only a single woman)] (in Spanish). Los 40. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "TV program valborgsmässoafton" [TV schedule Walpurgis Night]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. 30 April 1994. p. 32.

- ^ "Radio • valborgsmässoafton" [Radio • Walpurgis Night]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden. 30 April 1994. p. 31.

- ^ "Programmes TV – Samedi 30 avril" [TV programmes – Saturday 30 April]. TV8 (in French). Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland. 28 April 1994. pp. 10–15. Retrieved 21 October 2024 – via Scriptorium.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC One". Radio Times. 30 April 1994. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC Radio 2". Radio Times. 30 April 1994. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- ^ a b "Today's television". The Canberra Times. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 1 May 1994. p. 32. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via Trove.

- ^ "Zaterdag 30 april" [Saturday 30 April]. Brugsch Handelsblad (in Dutch). Bruges, Belgium. 29 April 1994. p. 66. Retrieved 4 July 2024 – via Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge.

- ^ "Televisie en radio zaterdag" [Television and radio Saturday]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). Heerlen, Netherlands. 30 April 1994. p. 43. Retrieved 24 October 2024 – via Delpher.

- ^ "Heute abend im Fernsehen" [Tonight on TV]. Grenz-Echo (in German). Eupen, Belgium. 30 April 1994. p. 27. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Alle tiders programoversigter – Lørdag den 30. april 1994" [All-time programme overviews – Saturday 30 April 1994]. DR. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Sjónvarp | Sjónvarpsskráin 29. apríl – 5. mai" [Television | TV Schedule 29 April – 5 May]. Oyggjatíðindi (in Faroese and Danish). Hoyvík, Faroe Islands. 29 April 1994. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Infomedia.

- ^ a b "KNR Aallakaatitassat/Programmer" [KNR Schedule]. Atuagagdliutit (in Kalaallisut and Danish). Nuuk, Greenland. 28 April 1994. p. 13. Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Timarit.is.

- ^ "على الشاشة الصغيرة - السبت ٣٠\٤\٩٤" [On the small screen – Saturday 30/04/94]. Al-Ittihad (in Arabic). Haifa, Israel. 29 April 1994. p. 6. Archived from the original on 3 November 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023 – via National Library of Israel.

- ^ "Jordan Times Daily Guide and Calendar | Jordan Television". The Jordan Times. Amman, Jordan. 30 April 1994. p. 2. Retrieved 5 November 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Sobota 30. april 1994" [Saturday 30 April 1994]. Vikend magazin (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia: Delo. 30 April – 6 May 1994. p. 20. Retrieved 4 June 2024 – via Digital Library of Slovenia.

- ^ "Spored za soboto" [Schedule for Saturday]. Delo (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia. 30 April 1994. p. 14. Retrieved 30 December 2024 – via Digital Library of Slovenia.

- ^ a b "러시아·동구권 첫 참가" [First participation from Russia and Eastern Europe]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Seoul, South Korea. 28 May 1994. p. 16. Retrieved 3 December 2024 – via Naver.

- ^ "TV Programları" [TV Programmes]. Cumhuriyet 2 (in Turkish). 30 April 1994. p. 4. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "TV Subota" [TV Saturday]. Borba (in Serbian). Belgrade, Serbia, Yugoslavia. 30 April 1994. p. 18. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024 – via Belgrade University Library.

- ^ "Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan – Rock 'n' Roll Kids". Irish Recorded Music Association (IRMA). Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ "Paul Harrington & Charlie McGettigan – Rock 'n' Roll Kids". Dutch Charts. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Bill Whelan – Riverdance". Irish Recorded Music Association (IRMA). Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "River Dance Facts". Irish Independent. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Top 20 of all time". Irish Recorded Music Association (IRMA). Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Riverdance at Royal Variety Performance 28 November 1994". Riverdance. 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b Egan, Barry (25 January 2020). "Riverdance: The couple behind seven minutes that shook the world". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Meet The Team of Creatives". Riverdance. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "MR riverdance steps up a gear". Irish Independent. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Riverdance: 25th anniversary show coming to Hull". The Hull Story. 8 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "North Macedonia – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Latvia – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest – New format" (Press release). European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 23 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Eurovision Song Contest: Two Semi-Finals in 2008" (Press release). European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Knox, David Blake (2015). Ireland and the Eurovision: The Winners, the Losers and the Turkey. Stillorgan, Dublin, Ireland: New Island Books. ISBN 978-1-84840-429-8.

- O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Thorsson, Leif; Verhage, Martin (2006). Melodifestivalen genom tiderna : de svenska uttagningarna och internationella finalerna [Melodifestivalen through the ages: the Swedish selections and international finals] (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Premium Publishing. ISBN 91-89136-29-2.