John Jay

John Jay | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, 1794 | |

| 1st Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office October 19, 1789 – June 29, 1795 | |

| Nominated by | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John Rutledge |

| 2nd Governor of New York | |

| In office July 1, 1795 – June 30, 1801 | |

| Lieutenant | Stephen Van Rensselaer |

| Preceded by | George Clinton |

| Succeeded by | George Clinton |

| United States Secretary of State | |

| Acting September 15, 1789 – March 22, 1790 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs | |

| Acting July 27, 1789 – September 15, 1789 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| In office December 21, 1784 – March 3, 1789 | |

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Robert R. Livingston |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| United States Minister to Spain | |

| In office September 27, 1779 – May 20, 1782 | |

| Appointed by | Second Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | William Short |

| 6th President of the Continental Congress | |

| In office December 10, 1778 – September 28, 1779 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Laurens |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Huntington |

| Delegate from New York to the Second Continental Congress | |

| In office December 7, 1778 – September 28, 1779 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Livingston |

| Succeeded by | Robert R. Livingston |

| In office May 10, 1775 – May 22, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Delegate from New York to the First Continental Congress | |

| In office September 5, 1774 – October 26, 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 23, 1745 New York City, Province of New York |

| Died | May 17, 1829 (aged 83) Bedford, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 6, including Peter and William |

| Relatives | Jay family Van Cortlandt family |

| Education | King's College (BA, MA) |

| Signature | |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

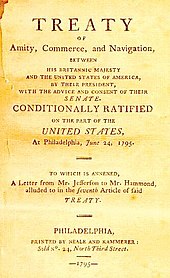

John Jay (December 23 [O.S. December 12], 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United States and from 1795 to 1801 as the second governor of New York. Jay directed U.S. foreign policy for much of the 1780s and was an important leader of the Federalist Party after the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788.

Jay was born into a wealthy family of merchants and New York City government officials of French Huguenot and Dutch descent. He became a lawyer and joined the New York Committee of Correspondence, organizing American opposition to British policies such as the Intolerable Acts in the leadup to the American Revolution. Jay was elected to the First Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and to the Second Continental Congress, where he served as its president. From 1779 to 1782, Jay served as the ambassador to Spain; he persuaded Spain to provide financial aid to the fledgling United States. He also served as a negotiator of the Treaty of Paris, in which Britain recognized American independence. Following the end of the war, Jay served as Secretary of Foreign Affairs, directing United States foreign policy under the Articles of Confederation government. He also served as the first Secretary of State on an interim basis.

A proponent of strong, centralized government, Jay worked to ratify the United States Constitution in New York in 1788. He was a co-author of The Federalist Papers along with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, and wrote five of the eighty-five essays. After the establishment of the new federal government, Jay was appointed by President George Washington the first Chief Justice of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1795. The Jay Court experienced a light workload, deciding just four cases over six years. In 1794, while serving as chief justice, Jay negotiated the highly controversial Jay Treaty with Britain. Jay received a handful of electoral votes in three of the first four presidential elections but never undertook a serious bid for the presidency.

Jay served as the governor of New York from 1795 to 1801. Although he successfully passed gradual emancipation legislation as governor of the state, he owned five slaves as late as 1800. In the waning days of President John Adams' administration, Jay was confirmed by the Senate for another term as chief justice, but he declined the position and retired to his farm in Westchester County, New York.

Early life

[edit]Family History

[edit]The Jays, a prominent merchant family in New York City, were descendants of Huguenots who had sought refuge in New York to escape religious persecution in France. In 1685, the Edict of Nantes had been revoked, thereby abolishing the civil and legal rights of Protestants, and the French Crown proceeded to confiscate their property. Among those affected was Jay's paternal grandfather, Auguste Jay. He moved from France to Charleston, South Carolina, and then New York, where he built a successful merchant empire.[1] Jay's father, Peter Jay (1704–1782), born in New York City in 1704, became a wealthy trader in furs, wheat, timber, and other commodities.[2]

Jay's mother was Mary Van Cortlandt (1705–1777), of Dutch ancestry, who had married Peter Jay in 1728 in the Dutch Church.[2] They had ten children together, seven of whom survived into adulthood.[3] Mary's father, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, was born in New Amsterdam in 1658. Cortlandt served in the New York Assembly, was twice elected as mayor of New York City, and held a variety of judicial and military offices. Both Mary and his son Frederick Cortlandt married into the Jay family.

Jay was born on December 23, 1745 (following the Gregorian calendar, December 12 following the Julian calendar), in New York City; three months later the family moved to Rye, New York. Peter Jay had retired from business following a smallpox epidemic; two of his children contracted the disease and suffered total blindness.[4]

Education

[edit]Jay spent his childhood in Rye. He was educated there by his mother until he was eight years old, when he was sent to New Rochelle to study under Anglican priest Pierre Stoupe.[5] In 1756, after three years, he returned to homeschooling in Rye under the tutelage of his mother and George Murray. In 1760, 14-year-old Jay entered King's College (later renamed Columbia College) in New York City.[6][7] There he made many influential friends, including his closest friend, Robert Livingston.[8] Jay took the same political stand as his father, a staunch Whig.[9] Upon graduating in 1764[10] he became a law clerk for Benjamin Kissam, a prominent lawyer, politician, and sought-after instructor in the law. In addition to Jay, Kissam's students included Lindley Murray.[3] Three years later, in 1767, as was the tradition at the time, Jay was promoted to Master of Arts.[11]

Entrance into law and politics

[edit]In 1768, after reading law and being admitted to the bar of New York, Jay, with the money from the government, established a legal practice and worked there until he opened his own law office in 1771.[3] He was a member of the New York Committee of Correspondence in 1774[12] and became its secretary, which was his first public role in the revolution.

Jay represented the "Radical Whig" faction that was interested in protecting property rights and in preserving the rule of law, while resisting what it regarded as British violations of colonial rights.[13] This faction feared the prospect of mob rule. Jay believed the British tax measures were wrong and thought Americans were morally and legally justified in resisting them, but as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774,[14] Jay sided with those who wanted conciliation with Parliament. Events such as the burning of Norfolk in January 1776 pushed Jay to support the Patriot camp. With the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, he worked tirelessly for the revolutionary cause and acted to suppress Loyalists. Jay evolved into first a moderate and then an ardent Patriot, because he had decided that all the colonies' efforts at reconciliation with Britain were fruitless and that the struggle for independence was inevitable.[15] In 1780, Jay was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.[16]

Marriage and family

[edit]

On April 28, 1774, Jay married Sarah Van Brugh Livingston, eldest daughter of the New Jersey Governor William Livingston. At the time of the marriage, Livingston was seventeen years old and Jay was twenty-eight.[17] Together they had six children: Peter Augustus, Susan, Maria, Ann, William, and Sarah Louisa. She accompanied Jay to Spain and later was with him in Paris, where they and their children resided with Benjamin Franklin at Passy.[18] Jay's brother-in-law Henry Brock Livingston was lost at sea through the disappearance of the Continental Navy ship Saratoga during the Revolutionary War. While Jay was in Paris, as a diplomat to France, his father died. This event forced extra responsibility onto Jay. His brother and sister Peter and Anna, both blinded by smallpox in childhood,[19] became his responsibility. His brother Augustus suffered from mental disabilities that required Jay to provide both financial and emotional support. His brother Fredrick was in constant financial trouble, causing Jay additional stress. Meanwhile, his brother James was in direct opposition in the political arena, joining the Loyalist faction of the New York State Senate at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, which made him an embarrassment to Jay's family.[20]

Jay family homes in Rye and Bedford

[edit]From the age of three months old until he attended Kings College in 1760, Jay was raised in Rye,[21] on a farm acquired by his father Peter in 1745 that overlooked Long Island Sound.[22] After negotiating the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War, Jay returned to his childhood home to celebrate with his family and friends in July 1784.[23] Jay inherited this property upon the death of his older brother Peter in 1813 after Jay had already established himself at Katonah. He conveyed the Rye property to his eldest son, Peter Augustus Jay, in 1822.

What remains of the original 400-acre (1.6 km2) property is a 23-acre (93,000 m2) parcel called the Jay Estate. In the center rises the 1838 Peter Augustus Jay House, built by Peter Augustus Jay over the footprint of his father's ancestral home, "The Locusts"; pieces of the original 18th-century farmhouse, were incorporated into the 19th-century structure. Stewardship of the site and several of its buildings for educational use was entrusted in 1990 by the New York State Board of Regents to the Jay Heritage Center.[24][25] In 2013, the non-profit Jay Heritage Center was also awarded stewardship and management of the site's landscape which includes a meadow and gardens.[26][27]

As an adult, Jay inherited land from his grandparents and built Bedford House, located near Katonah, New York, where he moved in 1801 with his wife Sarah to pursue retirement. This property passed down to their younger son William Jay and his descendants. It was acquired by New York State in 1958 and named "The John Jay Homestead". Today this 62 acre park is preserved as the John Jay Homestead State Historic Site.[28]

Both homes in Rye and Katonah have been designated National Historic Landmarks and are open to the public for tours and programs.

Personal views

[edit]Slavery

[edit]Every man of every color and description has a natural right to freedom.

—John Jay, February 27, 1792

The Jay family participated significantly in the slave trade, as investors and traders as well as slaveholders. For example, the New York Slavery Records Index records Jay's father and paternal grandfather as investors in at least 11 slave ships that delivered more than 120 slaves to New York between 1717 and 1733.[29] John Jay himself purchased, owned, rented out and manumitted at least 17 slaves during his lifetime.[30] He is not known to have owned or invested in any slave ships.[29] In 1783, one of Jay's slaves, a woman named Abigail, attempted to escape in Paris, but was found, imprisoned, and died soon after from illness.[30] Jay was irritated by her escape attempt, suggesting that she be left in prison for some time. To his biographer Walter Stahr, this reaction indicates that "however much [Jay] disliked slavery in the abstract, he could not understand why one of his slaves would run away."[31]

Despite being a founder of the New York Manumission Society, Jay is recorded as owning five slaves in the 1790 and 1800 U.S. censuses. He freed all but one by the 1810 census. Rather than advocating for immediate emancipation, he continued to purchase enslaved people and to manumit them once he considered their work to "have afforded a reasonable retribution."[32] Abolitionism following the American Revolution contained some Quaker and Methodist principles of Christian brotherly love but was also influenced by concerns about the growth of the Black population within the United States and the "degradation" of Black people under slavery.[33][34]

In 1774, Jay drafted the "Address to the People of Great Britain",[35] which compared American slavery to unpopular British policies.[36] Such comparisons between American slavery and British policies had been made regularly by Patriots starting with James Otis Jr., and took little account of the far harsher reality of slavery.[37] Jay was the founder and president of the New York Manumission Society in 1785, which organized boycotts against newspapers and merchants involved in the slave trade and provided legal counsel to free Blacks.[38]

The Society helped enact the 1799 law for gradual emancipation of slaves in New York, which Jay signed into law as governor. "An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery" provided that, from July 4, 1799, all children born to slave parents would be free (subject to lengthy apprenticeships) and that slave exports would be prohibited. These same children would be required to serve the mother's owner until age 28 for males and age 25 for females. It did not provide government payment of compensation to slave owners but failed to free people who were already enslaved as of 1799. The act provided legal protection and assistance for free Blacks kidnapped for the purposes of being sold into slavery.[39] All slaves were emancipated by July 4, 1827.[40][41][42][43][44]

In the close 1792 gubernatorial election, Jay's antislavery work was thought to hurt his election chances in upstate New York Dutch areas, where slavery was still practiced.[45] In 1794, in the process of negotiating the Jay Treaty with the British, Jay angered many Southern slave owners when he dropped their demands for compensation for American slaves who had been freed and transported by the British to other areas after the Revolution.[46]

Religion

[edit]Jay was a member of the Church of England and later of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America after the American Revolution. Since 1785, Jay had been a warden of Trinity Church, New York. As Congress's Secretary for Foreign Affairs, he supported the proposal after the Revolution that the Archbishop of Canterbury approve the ordination of bishops for the Episcopal Church in the United States.[47] He argued unsuccessfully in the provincial convention for a prohibition against Catholics holding office.[48] While considering New York's Constitution, Jay also suggested erecting "a wall of brass around the country for the exclusion of Catholics."[49]

Jay, who served as vice-president (1816–1821) and president (1821–1827) of the American Bible Society,[50]believed that the most effective way of ensuring world peace was through propagation of the Christian gospel. In a letter addressed to Pennsylvania House of Representatives member John Murray, dated October 12, 1816, Jay wrote, "Real Christians will abstain from violating the rights of others, and therefore will not provoke war. Almost all nations have peace or war at the will and pleasure of rulers whom they do not elect, and who are not always wise or virtuous. Providence has given to our people the choice of their rulers, and it is the duty, as well as the privilege and interest, of our Christian nation to select and prefer Christians for their rulers."[51] He also expressed a belief that the moral precepts of Christianity were necessary for good government, saying, "No human society has ever been able to maintain both order and freedom, both cohesiveness and liberty apart from the moral precepts of the Christian Religion. Should our Republic ever forget this fundamental precept of governance, we will then, be surely doomed."[52][better source needed]

During the American Revolution

[edit]Those who own the country ought to govern it.

—John Jay[53]

Having established a reputation as a reasonable moderate in New York, Jay was elected to serve as delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses which debated whether the colonies should declare independence. Jay was originally in favor of rapprochement. He helped write the Olive Branch Petition which urged the British government to reconcile with the colonies. As the necessity and inevitability of war became evident, Jay threw his support behind the revolution and the Declaration of Independence. Jay's views became more radical as events unfolded; he became an ardent separatist and attempted to move New York towards that cause.

In 1774, upon the conclusion of the Continental Congress, Jay elected to return to New York.[54] There he served on New York City's Committee of Sixty,[55] where he attempted to enforce a non-importation agreement passed by the First Continental Congress.[54] Jay was elected to the third New York Provincial Congress, where he drafted the Constitution of New York, 1777;[56] his duties as a New York Congressman prevented him from voting on or signing the Declaration of Independence.[54] Jay served for several months on the New York Committee to Detect and Defeat Conspiracies, which monitored and combated Loyalist activity.[57] New York's Provincial Congress elected Jay the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature on May 8, 1777,[54][58] which he served on for two years.[54]

The Continental Congress turned to Jay, a political adversary of the previous president Henry Laurens, only three days after Jay became a delegate and elected him President of the Continental Congress. In previous congresses, Jay had moved from a position of seeking conciliation with Britain to advocating separation sooner than Laurens. Eight states voted for Jay and four for Laurens. Jay served as President of the Continental Congress from December 10, 1778, to September 28, 1779. It was a largely ceremonial position without real power, and indicated the resolve of the majority and the commitment of the Continental Congress.[59]

As a diplomat

[edit]Minister to Spain

[edit]On September 27, 1779, Jay was appointed Minister to Spain. His mission was to get financial aid, commercial treaties and recognition of American independence. The royal court of Spain refused to officially receive Jay as the Minister of the United States,[60] as it refused to recognize American independence until 1783, fearing that such recognition could spark revolution in their own colonies. Jay, however, convinced Spain to loan $170,000 to the U.S. government.[61] He departed Spain on May 20, 1782.[60]

Peace Commissioner

[edit]

On June 23, 1782, Jay reached Paris, where negotiations to end the American Revolutionary War would take place.[62] Benjamin Franklin was the most experienced diplomat of the group, and thus Jay wished to lodge near him, in order to learn from him.[63] The United States agreed to negotiate with Britain separately, then with France.[64] In July 1782, the Earl of Shelburne offered the Americans independence, but Jay rejected the offer on the grounds that it did not recognize American independence during the negotiations; Jay's dissent halted negotiations until the fall.[64] The final treaty dictated that the United States would have Newfoundland fishing rights, Britain would acknowledge the United States as independent and would withdraw its troops in exchange for the United States ending the seizure of Loyalist property and honoring private debts.[64][65] The treaty granted the United States independence, but left many border regions in dispute, and many of its provisions were not enforced.[64] John Adams credited Jay with having the central role in the negotiations noting he was "of more importance than any of the rest of us."[66]

Jay's peacemaking skills were further applauded by New York Mayor James Duane on October 4, 1784. At that time, Jay was summoned from his family seat in Rye to receive "the Freedom" of New York City as a tribute to his successful negotiations.[67]

Secretary of Foreign Affairs

[edit]

Jay served as the second Secretary of Foreign Affairs from 1784 to 1789, when in September, Congress passed a law giving certain additional domestic responsibilities to the new department and changing its name to the Department of State. Jay served as acting Secretary of State until March 22, 1790. Jay sought to establish a strong and durable American foreign policy: to seek the recognition of the young independent nation by powerful and established foreign European powers; to establish a stable American currency and credit supported at first by financial loans from European banks; to pay back America's creditors and to quickly pay off the country's heavy War-debt; to secure the infant nation's territorial boundaries under the most-advantageous terms possible and against possible incursions by the Indians, Spanish, the French and the English; to solve regional difficulties among the colonies themselves; to secure Newfoundland fishing rights; to establish a robust maritime trade for American goods with new economic trading partners; to protect American trading vessels against piracy; to preserve America's reputation at home and abroad; and to hold the country together politically under the fledgling Articles of Confederation.[68]

The Federalist Papers, 1788

[edit]With equal pleasure I have as often taken notice, that Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country, to one united people; a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established their general Liberty and Independence.

—John Jay, Federalist No. 2[69][70][71]

Jay believed his responsibility was not matched by a commensurate level of authority, so he joined Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in advocating for a stronger government than the one dictated by the Articles of Confederation.[3][72] He argued in his "Address to the People of the State of New-York, on the Subject of the Federal Constitution" that the Articles of Confederation were too weak and an ineffective form of government, contending:

The Congress under the Articles of Confederation may make war, but are not empowered to raise men or money to carry it on—they may make peace, but without power to see the terms of it observed—they may form alliances, but without ability to comply with the stipulations on their part—they may enter into treaties of commerce, but without power to [e]nforce them at home or abroad ... —In short, they may consult, and deliberate, and recommend, and make requisitions, and they who please may regard them.[73]

Jay did not attend the Constitutional Convention but joined Hamilton and Madison in aggressively arguing in favor of the creation of a new and more powerful, centralized but balanced system of government. Writing under the shared pseudonym of "Publius",[74] they articulated this vision in The Federalist Papers, a series of eighty-five articles written to persuade New York state convention members to ratify the proposed Constitution of the United States.[75] Jay wrote the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixty-fourth articles. The second through the fifth are on the topic "Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence". The sixty-fourth discusses the role of the Senate in making foreign treaties.[76]

The Jay Court

[edit]In September 1789, Jay declined George Washington's offer of the position of Secretary of State (which was technically a new position but would have continued Jay's service as Secretary of Foreign Affairs). Washington responded by offering him the new title, which Washington stated "must be regarded as the keystone of our political fabric," as Chief Justice of the United States, which Jay accepted. Washington officially nominated Jay on September 24, 1789, the same day he signed the Judiciary Act of 1789 (which created the position of Chief Justice) into law.[72] Jay was unanimously confirmed by the US Senate on September 26, 1789; Washington signed and sealed Jay's commission the same day. Jay swore his oath of office on October 19, 1789.[77] Washington also nominated John Rutledge, William Cushing, Robert Harrison, James Wilson, and John Blair Jr. as Associate Judges.[78] Harrison declined the appointment, however, and Washington appointed James Iredell to fill the final seat on the Court.[79] Jay would later serve with Thomas Johnson,[citation needed] who took Rutledge's seat,[80] and William Paterson, who took Johnson's seat.[80] While Chief Justice, Jay was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1790.[81] Jay served as Circuit Justice for the Eastern Circuit from the Spring of 1790, until the Spring of 1792.[82] He served as Circuit Justice for the Middle Circuit from the Spring of 1793, until the Spring of 1794.[82]

The Court's business through its first three years primarily involved the establishment of rules and procedure; reading of commissions and admission of attorneys to the bar; and the Justices' duties in "riding circuit", or presiding over cases in the circuit courts of the various federal judicial districts. No convention then precluded the involvement of Supreme Court Justices in political affairs, and Jay used his light workload as a Justice to participate freely in the business of Washington's administration.

Jay used his circuit riding to spread word throughout the states of Washington's commitment to neutrality and published reports of French minister Edmond-Charles Genet's campaign to win American support for France. However, Jay also established an early precedent for the Court's independence in 1790, when Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton wrote to Jay requesting the Court's endorsement of legislation that would assume the debts of the states. Jay replied that the Court's business was restricted to ruling on the constitutionality of cases being tried before it and refused to allow it to take a position for or against the legislation.[83]

For his work as chief justice, Jay was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by the University of Edinburgh on May 17, 1792.[84][85]

Cases

[edit][T]he people are the sovereign of this country, and consequently ... fellow citizens and joint sovereigns cannot be degraded by appearing with each other in their own courts to have their controversies determined. The people have reason to prize and rejoice in such valuable privileges, and they ought not to forget that nothing but the free course of constitutional law and government can ensure the continuance and enjoyment of them. For the reasons before given, I am clearly of opinion that a State is suable by citizens of another State.

—John Jay in the court opinion of Chisholm v. Georgia[86]

The Jay Court's first case did not occur until early in the Court's third term, with West v. Barnes (1791). The Court had an early opportunity to establish the principle of judicial review in the United States with the case, which involved a Rhode Island state statute permitting the lodging of a debt payment in paper currency. Instead of grappling with the constitutionality of the law, however, the Court unanimously decided the case on procedural grounds, strictly interpreting statutory requirements.[78]

Hayburn's Case (1792) concerned whether a federal statute could require the courts to decide whether petitioning veterans of the American Revolution qualified for pensions, a non-judicial function. The Jay Court wrote a letter to President Washington to say that determining whether petitioners qualified was an "act ... not of a judicial nature"[87] and that because the statute allowed the legislative branch and the executive branch to revise the court's ruling, the statute violated the separation of powers of the US Constitution.[87][88][89]

In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the Jay Court had to decide if suits against state governments by state citizens could be heard in federal court.[90] In a 4–1 ruling (Iredell dissented, and Rutledge did not participate), the Jay Court ruled in favor of two South Carolina Loyalists whose land had been seized by Georgia. That ruling sparked debate, as it implied that old debts must be paid to Loyalists.[78] The ruling was overturned when the Eleventh Amendment was ratified, which stated that a state could not be sued by a citizen of another state or foreign country.[3][78] The case was brought again to the Supreme Court in Georgia v. Brailsford, and the Court reversed its decision.[91][92] However, Jay's original Chisholm decision established that states were subject to judicial review.[90][93]

In Georgia v. Brailsford (1794), the Court upheld jury instructions stating "you [jurors] have ... a right to take upon yourselves to ... determine the law as well as the fact in controversy." Jay noted for the jury the "good old rule, that on questions of fact, it is the province of the jury, on questions of law, it is the province of the court to decide," but that amounted to no more than a presumption that the judges were correct about the law. Ultimately, "both objects [the law and the facts] are lawfully within your power of decision."[94][95]

1792 campaign for Governor of New York

[edit]In 1792, Jay was the Federalist candidate for governor of New York, but he was defeated by Democratic-Republican George Clinton. Jay received more votes than George Clinton; but, on technicalities, the votes of Otsego, Tioga and Clinton counties were disqualified and, therefore, not counted, giving George Clinton a slight plurality.[96] The State constitution said that the cast votes shall be delivered to the secretary of state "by the sheriff or his deputy"; but, for example, the Otsego County Sheriff's term had expired, so that legally, at the time of the election, the office of Sheriff was vacant and the votes could not be brought to the State capital. Clinton partisans in the State legislature, the State courts, and Federal offices were determined not to accept any argument that this would, in practice, violate the constitutional right to vote of the voters in these counties. Consequently, these votes were disqualified.[97]

Jay Treaty

[edit]

Relations with Britain verged on war in 1794. British exports dominated the U.S. market, while American exports were hamstrung by British trade restrictions and tariffs. Britain still occupied northern forts that they had agreed to abandon in the Treaty of Paris, as the Americans had refused to pay debts owed to British creditors or halt the confiscation of Loyalist properties. In addition, the Royal Navy impressed U.S. sailors who were alleged to be British deserters from the Navy, and seized almost 300 American merchant ships who were trading with the French West Indies between 1793 and 1794.[98] Madison proposed a trade war, "[a] direct system of commercial hostility with Great Britain," assuming that Britain was so weakened by its war with France that it would agree to American terms and not declare war.[99]

Washington rejected that policy and sent Jay as a special envoy to Great Britain to negotiate a new treaty; Jay remained Chief Justice. Washington had Alexander Hamilton write instructions for Jay that were to guide him in the negotiations.[100] In March 1795, the resulting treaty, known as the Jay Treaty, was brought to Philadelphia.[100] When Hamilton, in an attempt to maintain good relations, informed Britain that the United States would not join the Second League of Armed Neutrality, Jay lost most of his leverage. The treaty resulted in Britain withdrawing from their northwestern forts[101] and granted the U.S. "most favored nation" status.[98] U.S. merchants were also granted restricted commercial access to the British West Indies.[98]

The treaty did not resolve American grievances about neutral shipping rights and impressment,[46] and the Democratic-Republicans denounced it, but Jay, as Chief Justice, decided not to take part in the debates.[102] The Royal Navy's continued impressment of American citizens would be a cause of the War of 1812.[103] The failure to receive compensation for American slaves which were freed by the British and transported away during the Revolutionary War "was a major reason for the bitter Southern opposition".[104] Jefferson and Madison, fearing that a commercial alliance with aristocratic Britain might undercut American republicanism, led the opposition. However, Washington put his prestige behind the treaty, and Hamilton and the Federalists mobilized public opinion.[105] The Senate ratified the treaty by a 20–10 vote, exactly by the two-thirds majority required.[98][101]

Democratic-Republicans were incensed at what they perceived as a betrayal of American interests, and Jay was denounced by protesters with such graffiti as "Damn John Jay! Damn everyone who won't damn John Jay!! Damn everyone that won't put lights in his windows and sit up all night damning John Jay!!!" One newspaper editor wrote, "John Jay, ah! the arch traitor – seize him, drown him, burn him, flay him alive."[106] Jay himself quipped that he could travel at night from Boston to Philadelphia solely by the light of his burning effigies.[107]

Governor of New York

[edit]

While in Britain, Jay was elected in May 1795, as the second governor of New York (succeeding George Clinton) as a Federalist. He resigned from the Supreme Court service on June 29, 1795, and served six years as governor until 1801.

As governor, he received a proposal from Hamilton to gerrymander New York for the presidential election of 1796; he marked the letter "Proposing a measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt", and filed it without replying.[108] President John Adams then renominated him to the Supreme Court; the Senate quickly confirmed him, but he declined, citing his own poor health[72] and the court's lack of "the energy, weight and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government."[109] After Jay's rejection of the position, Adams successfully nominated John Marshall as Chief Justice.

While governor, Jay ran in the 1796 presidential election, winning five electoral votes, and in the 1800 election he won one vote cast to prevent a tie between the two main Federalist candidates.

Retirement from politics

[edit]In 1801, Jay declined both the Federalist renomination for governor and a Senate-confirmed nomination to resume his former office as Chief Justice of the United States and retired to the life of a farmer in Westchester County, New York. Soon after his retirement, his wife died.[110] Jay remained in good health, continued to farm and, with one notable exception, stayed out of politics.[111] In 1819, he wrote a letter condemning Missouri's bid for admission to the union as a slave state, saying that slavery "ought not to be introduced nor permitted in any of the new states."[112]

Midway through Jay's retirement in 1814, both he and his son Peter Augustus Jay were elected members of the American Antiquarian Society.[113]

Death

[edit]On the night of May 14, 1829, Jay was stricken with palsy, probably caused by a stroke. He lived for three more days, dying in Bedford, New York, on May 17.[114] He was the last surviving President of the Continental Congress and also the last surviving delegate to the First Continental Congress. Jay had chosen to be buried in Rye, where he lived as a boy. In 1807, he had transferred the remains of his wife Sarah Livingston and those of his colonial ancestors from the family vault in the Bowery in Manhattan to Rye, establishing a private cemetery. Today, the Jay Cemetery is an integral part of the Boston Post Road Historic District, adjacent to the historic Jay Estate. The Cemetery is maintained by the Jay descendants and closed to the public. It is the oldest active cemetery associated with a figure from the American Revolution.

Legacy

[edit]

Place names

[edit]Geographic locations

[edit]Several geographical locations within his home state of New York were named for him, including the colonial Fort Jay on Governors Island and John Jay Park in Manhattan which was designed in part by his great-great-granddaughter Mary Rutherfurd Jay. Other places named for him include the towns of Jay in Maine, New York, and Vermont; Jay County, Indiana.[115] Mount John Jay, also known as Boundary Peak 18, a summit on the border between Alaska and British Columbia, Canada, is also named for him,[116][117] as is Jay Peak in northern Vermont.[118]

Schools and universities

[edit]The John Jay College of Criminal Justice, formerly known as the College of Police Science at City University of New York, was renamed for Jay in 1964.

At Columbia University, exceptional undergraduates are designated John Jay Scholars,[119] and one of that university's undergraduate dormitories is known as John Jay Hall.[120] The university also hands out the John Jay Awards to outstanding alumni of Columbia College.[121]

In suburban Pittsburgh, the John Jay Center houses the School of Engineering, Mathematics and Science at Robert Morris University.

High schools named after Jay include:

Postage

[edit]

In Jay's hometown of Rye, New York, the Rye Post Office issued a special cancellation stamp on September 5, 1936. To further commemorate Jay, a group led by Congresswoman Caroline Love Goodwin O'Day commissioned painter Guy Pene du Bois to create a mural for the post office's lobby, with federal funding from the Works Progress Administration. Titled John Jay at His Home, the mural was completed in 1938.

On December 12, 1958, the United States Postal Service released a 15¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Jay.[122]

Papers

[edit]The Selected Papers of John Jay is an ongoing endeavor by scholars at Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library to organize, transcribe and publish a wide range of politically and culturally important letters authored by and written to Jay that demonstrate the depth and breadth of his contributions as a nation builder. More than 13,000 documents from over 75 university and historical collections have been compiled and photographed to date. A selection of Jay's papers are available in a free searchable database on the Founders Online website maintained by the National Archives.[123]

Popular media

[edit]John Jay's childhood home in Rye, "The Locusts", was immortalized by novelist James Fenimore Cooper in his first successful novel The Spy; this book about counterespionage during the Revolutionary War was based on a tale that Jay told Cooper from his own experience as a spymaster in Westchester County.[124][125]

Jay was portrayed by Tim Moyer in the 1984 TV miniseries George Washington. In its 1986 sequel miniseries, George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation, he was portrayed by Nicholas Kepros.

Notable descendants

[edit]Jay had six children, including Peter Augustus Jay and abolitionist William Jay. In later generations, Jay's descendants included physician John Clarkson Jay (1808–1891), lawyer and diplomat John Jay (1817–1894), Colonel William Jay (1841–1915), diplomat Peter Augustus Jay (1877–1933), writer John Jay Chapman (1862–1933), philanthropist William Jay Schieffelin (1866–1955), banker Pierre Jay (1870–1949), horticulturalist Mary Rutherfurd Jay (1872–1953), and academic John Jay Iselin (1933–2008). Jay was also a direct ancestor of Adam von Trott zu Solz (1909–1944), a resistance fighter against Nazism.

See also

[edit]- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of United States Supreme Court cases prior to the Marshall Court

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pellew, George: "American Statesman John Jay", p. 1. Houghton Mifflin, 1890

- ^ a b Stahr, Walter (2006). John Jay: Founding Father. Continuum Publishing Group. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-8264-1879-1. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "A Brief Biography of John Jay". The Papers of John Jay. Columbia University. 2002. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Clary, Suzanne. "From a Peppercorn to a Path Through History" Archived March 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Upper East Side Magazine, Weston Magazine Publishers, Issue 53, October 2014.

- ^ Cushman, Clare. The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012 Archived June 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The Supreme Court Historical Society, SAGE Publications, 2012.

- ^ "Jay, John (1745–1829)". World of Criminal Justice, Gale. Farmington: Gale, 2002. Credo Reference. Web. September 24, 2012.

- ^ Stahr, p. 9

- ^ Stahr, p. 12 Archived September 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pellew p. 6

- ^ Barnard edu Archived February 22, 2001, at the Wayback Machine retrieved August 31, 2008

- ^ Columbia College (New York, N. Y. ) (1826). Catalogue of Columbia College in the City of New-York : embracing the names of its trustees, officers, and graduates, together with a list of all academical honours conferred by the institution from A.D. 1758 to A.D. 1826, inclusive. U.S. National Library of Medicine. New York : Printed by T. and J. Swords.

- ^ "John Jay". www.ushistory.org. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ Roger J. Champagne, "New York's Radicals and the Coming of Independence." Journal of American History 51.1 (1964): 21-40. online

- ^ "John Jay Nomination to the First Continental Congress". Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ Klein (2000)

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Urbanities: "The Education of John Jay"." City Journal. (Winter 2010): 15960 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: September 26, 2012.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jay, John (1892). . In Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J. (eds.). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Du Bois, John Jay (July 27, 2014). "Jay Family Time Line". Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- ^ Morris, Richard. John Jay: The Winning of the Peace. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1980.

- ^ "Westchester Building, Rye, N.Y.". New York Evening Post. May 13, 1922.

- ^ The Library of Congress, Local Legacies, The Jay Heritage Center http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/legacies/loc.afc.afc-legacies.200003400/ Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wilcox, Arthur Russell. The Bar of Rye Township Archived March 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1918.

- ^ Clement, Douglas P. (March 11, 2016). "Clement, Douglas P.,"At the Jay Heritage Center in Rye: Young Americans," 'The New York Times,' New York, New York, March 10, 2016". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ "News and Events: Pace Law School, New York Law School, located in New York 20 miles north of NY City. Environmental Law". www.pace.edu. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Jay Property Estate Restoration/Maintenance Archived January 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Westchester County, New York, ACT-2012-173, Adopted November 26, 2012.

- ^ Cary, Bill. Jay gardens in Rye to get $1.5 million makeover Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The Journal News (Westchester, New York), February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Friends of John Jay Homestead". www.johnjayhomestead.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Benton, Ned; Peters, Judy Lynne (2017). "Slavery and the Extended Family of John Jay". New York Slavery Records Index: Records of Enslaved Persons and Slave Holders in New York from 1525 though the Civil War. New York: John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Martha S. (November 23, 2021). "Enslaved to a Founding Father, She Sought Freedom in France". The New York Times.

- ^ Stahr, Walter (2012). "Chapter 8". John Jay: Founding Father. New York City: Diversion Books. ISBN 978-1-938120-51-0. OCLC 828922149.

- ^ Sudderth, Jake. "John Jay and Slavery". Columbia University Libraries. New York City: Columbia University. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Everill, B. (2013). Abolition and Empire in Sierra Leone and Liberia. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137028679.

- ^ Franklin, Benjamin. "Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind". Founders' Archives. Washington D.C: National Archives. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Address to the People of Great Britain. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ Jay, Jay (1774). Address to the People of Great Britain. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

When a Nation, lead to greatness by the hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the Glory that heroism, munificence, and humanity can bestow, descends to the ungrateful task of forging chains for her friends and children, and instead of giving support to Freedom, turns advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her Rulers.

- ^ Breen, T. H (2001). Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Kennedy, Roger G. (1999). Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0195130553.

- ^ McManus, Edgar J. (2001). History of Negro Slavery in New York. New York City: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0815628941.

- ^ Sudderth, Jake (2002). "John Jay and Slavery". New York City: Columbia University. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ Paul Finkelman, editor, Encyclopedia of African American History 1619–1895 Archived September 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, 2006, p. 237

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (2002) [1982]. The American Revolution: A History. New York City: Modern Library. p. 114. ISBN 978-0679640578.

- ^ Kolchin, Peter (2003) [1993]. American Slavery: 1619–1877. New York City: Hill and Wang. p. 73. ISBN 978-0809016303.

- ^ Simon Schama, Rough Passage

- ^ Herbert S. Parmet and Marie B. Hecht, Aaron Burr (1967) p. 76

- ^ a b Baird, James. "The Jay Treaty". www.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Crippen II, Alan R. (2005). "John Jay: An American Wilberforce?". John Jay Institute. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- ^ Kaminski, John P. (March 2002). "Religion and the Founding Fathers". Annotation: The Newsletter of the National Historic Publications and Records Commission. 30 (1). ISSN 0160-8460. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Kenneth C. (July 3, 2007). "Opinion | The Founding Immigrants". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ "John Jay" Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. WallBuilders

- ^ Jay, William (1833). The Life of John Jay: With Selections from His Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers. New York: J. & J. Harper. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-8369-6858-3. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Loconte, Joseph (September 26, 2005). "Why Religious Values Support American Values" Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Heritage Foundation

- ^ Becker, Carl (1920). "The Quarterly journal of the New York State Historical Association". 1: 2. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e "Jay and New York". The Papers of John Jay. Columbia University. 2002. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Stahr, p. 443

- ^ "The First Constitution, 1777". The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York. New York State Unified Court System. Archived from the original on August 6, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Ketchum, Richard M. (2002). Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution Came to New York. Henry Holt & Co. p. 368. ISBN 9780805061192.

- ^ "Portrait Gallery". The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York. New York State Unified Court System. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Calvin C. Jillson; Rick K. Wilson (1994). Congressional Dynamics: Structure, Coordination, and Choice in the First American Congress, 1774–1789. Stanford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780804722933. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "United States Department of State: Chiefs of Mission to Spain". Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "John Jay". Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Pellew p. 166

- ^ Pellew p. 170

- ^ a b c d "Treaty of Paris, 1783". U.S. Department of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ "The Paris Peace Treaty of 1783". The University of Oklahoma College of Law. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008.

- ^ "What you should know about forgotten founding father John Jay". PBS Newshour. July 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "American Occurrences". Warden & Russell's Massachusetts Sentinel. October 27, 1784.

- ^ Whitelock p. 181

- ^ "Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History". Guides.loc.gov. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Millican, Edward (July 15, 2014). One United People: The Federalist Papers and the National Idea. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813161372. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "John Jay Quotes - Federalist No. 2". Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c "John Jay". Find Law. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ "Extract from an Address to the people of the state of New-York, on the subject of the federal Constitution". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ WSU Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine retrieved August 31, 2008

- ^ "The Federalist Papers". Primary Document in American History. The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ "Federalist Papers Authored by John Jay". Foundingfathers.info. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ "The Supreme Court of the United States – History". United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "The Jay Court ... 1789–1793". The Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold J. Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium 352 (3d ed. 2003).

- ^ a b "Appointees Chart". The Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter J" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ a b John Jay at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ John Jay Archived April 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Leftjustified.com

- ^ "Honorary graduate details | The University of Edinburgh". www.scripts.sasg.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ Hofstedt, Matthew (March 2021). "The Switch to Black: Revisiting Early Supreme Court Robes". Journal of Supreme Court History. 46 (1): 13–41. doi:10.1111/jsch.12255. ISSN 1059-4329. S2CID 236746654.

- ^ "Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U. S. 419 (1793) (Court Opinion)". Justia & Oyez. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "Hayburn's Case, 2 U. S. 409 (1792)". Justia and Oyez. Archived from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Pushaw, Robert J. Jr. (November 1998). "Book Review: Why the Supreme Court Never Gets Any "Dear John" Letters: Advisory Opinions in Historical Perspective: Most Humble Servants: The Advisory Role of Early Judges. By Stewart Jay". Georgetown Law Journal. 87. Bnet: 473. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Hayburn's Case". Novelguide.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ a b "Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793)". The Oyez Project. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia v. Brailsford, Powell & Hopton, 3 U.S. 3 Dall. 1 1 (1794)". Oyez & Justia. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ "John Jay (1745–1829)". The Free Library. Farlex. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ Johnson (2000)

- ^ We the Jury by Jefferey B Abramson, pp. 75–76

- ^ Mann, Neighbors and Strangers, pp. 71, 75

- ^ Jenkins, John (1846). History of Political Parties in the State of New-York. Alden & Markham. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, James; Williams, Melvin E.; Conklin, Edwin P.; Fitzpatrick, Benedict, eds. (1927), "Chapter III. Politics in New York State. Federal Period to 1800.", History of New York State, 1523–1927 (PDF), vol. 4, New York City, Chicago: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., pp. 1491–92, hdl:2027/mdp.39015067924855, Wikidata Q114149633

- ^ a b c d "John Jay's Treaty, 1794–95". U.S. Department of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Elkins and McKitrick, p. 405

- ^ a b Kafer p. 87

- ^ a b "Jay's Treaty". Archiving Early America. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Estes (2002)

- ^ "Wars – War of 1812". USAhistory.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ quoting Don Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic (2002) p. 93; Frederick A. Ogg, "Jay's Treaty and the Slavery Interests of the United States". Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1901 (1902) 1:275–86 in JSTOR.

- ^ Todd Estes, "Shaping the Politics of Public Opinion: Federalists and the Jay Treaty Debate". Journal of the Early Republic (2000) 20(3): 393–422. ISSN 0275-1275; online at JSTOR Archived October 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Walter A. McDougall, Walter A. (1997). Promised Land, Crusader State: The American Encounter with the World Since 1776. Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-395-90132-8. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ "Biographies of the Robes: John Jay". Supreme Court History: The Court and Democracy. pbs.org. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Monaghan, pp. 419–21; Adair, Douglass; Marvin Harvey (April 1955). "Was Alexander Hamilton a Christian Statesman". The William and Mary Quarterly. 12 (3rd Ser., Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander Hamilton: 1755–1804). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 308–29. doi:10.2307/1920511. JSTOR 1920511.

- ^ Laboratory of Justice, The Supreme Court's 200 Year Struggle to Integrate Science and the Law, by David L. Faigman, First edition, 2004, p. 34; Smith, Republic of Letters, 15, 501

- ^ Whitelock p. 327

- ^ Whitelock p. 329

- ^ Jay, John (November 17, 1819). "John Jay to Elias Boudinot". The Papers of John Jay. Columbia University.

- ^ "American Antiquarian Society Members Directory". Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Whitelock p. 335

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 168. Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "John Jay, Mount". BC Geographical Names.

- ^ "Mount John Jay". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 168. Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "John Jay National Scholars Program". Columbia College Alumni Association. December 14, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "John Jay Hall | Columbia Housing". housing.columbia.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "John Jay Awards". Columbia College Alumni Association. December 14, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "John Jay Commemorative Stamp". U.S. Stamp Gallery. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- ^ "Founders Online News: Papers of John Jay added to Founders Online". archives.gov. Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration. September 15, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Clary, Suzanne.James Fenimore Copper and Spies in Rye Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. My Rye, 2010.

- ^ Hicks, Paul. The Spymaster and the Author Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The Rye Record, December 7, 2014.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Bemis, Samuel F. (1923). Jay's Treaty: A Study in Commerce and Diplomacy. New York City: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 978-0-8371-8133-2.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. "John Jay." [1] Archived January 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine in Bemis, ed. The American Secretaries of State and their diplomacy V.1 (1928) pp. 193–298

- Brecher, Frank W. Securing American Independence: John Jay and the French Alliance. Praeger, 2003. 327 pp. Archived May 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Casto, William R. The Supreme Court in the Early Republic: The Chief Justiceships of John Jay and Oliver Ellsworth. U. of South Carolina Press, 1995. 267 pp.

- Combs, Jerald. A. The Jay Treaty: Political Background of Founding Fathers (1970) (ISBN 0-520-01573-8); concludes the Federalists "followed the proper policy" because the treaty preserved peace with Britain

- Dillon, Mark C. The First Chief Justice: John Jay and the Struggle of a New Nation (State University of New York Press, 2022. online review

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788–1800. (1994), detailed political history

- Estes, Todd. "John Jay, the Concept of Deference, and the Transformation of Early American Political Culture." Historian (2002) 65(2): 293–317. ISSN 0018-2370 see online[permanent dead link]

- Ferguson, Robert A. "The Forgotten Publius: John Jay and the Aesthetics of Ratification." Early American Literature (1999) 34(3): 223–40. ISSN 0012-8163 see online

- Johnson, Herbert A. "John Jay and the Supreme Court." New York History 2000 81(1): 59–90. ISSN 0146-437X

- Kaminski, John P. "Honor and Interest: John Jay's Diplomacy During the Confederation." New York History (2002) 83(3): 293–327. ISSN 0146-437X see online

- Kaminski, John P. "Shall We Have a King? John Jay and the Politics of Union." New York History (2000) 81(1): 31–58. ISSN 0146-437X see online

- Kaminski, John P., and C. Jennifer Lawton. "Duty and Justice at “Every Man's Door”: The Grand Jury Charges of Chief Justice John Jay, 1790–1794." Journal of Supreme Court History 31.3 (2006): 235-251.

- Kefer, Peter (2004). Charles Brockden Brown's Revolution and the Birth of American Gothic.

- Klein, Milton M. "John Jay and the Revolution." New York History (2000) 81(1): 19–30. ISSN 0146-437X

- Littlefield, Daniel C. "John Jay, the Revolutionary Generation, and Slavery" New York History 2000 81(1): 91–132. ISSN 0146-437X see online

- Magnet, Myron. "The Education of John Jay" City Journal (Winter 2010) 20#1 online Archived February 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Monaghan, Frank. John Jay: Defender of Liberty 1972. on abolitionism

- Morris, Richard B. The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence 1965.

- Morris, Richard B. Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries 1973. chapter on Jay

- Morris, Richard B. Witness at the Creation; Hamilton, Madison, Jay and the Constitution 1985.

- Morris, Richard B. ed. John Jay: The Winning of the Peace 1980. 9780060130480

- Perkins, Bradford. The First Rapprochement; England and the United States: 1795–1805 Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1955.

- Stahr, Walter (2005). John Jay: Founding Father. New York & London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-444-7. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

Primary sources

[edit]- Freeman, Landa M., Louise V. North, and Janet M. Wedge, eds. Selected Letters of John Jay and Sarah Livingston Jay: Correspondence by or to the First Chief Justice of the United States and His Wife (2005)

- Morris, Richard B. ed. John Jay: The Making of a Revolutionary; Unpublished Papers, 1745–1780 1975.

- Nuxoll, Elizabeth M., and others, eds. The Selected Papers of John Jay (University of Virginia Press; 2010–2022) Seven-volume edition of Jay's incoming and outgoing correspondence; also online. see article on The Selected Papers of John Jay

External links

[edit]- "John Jay (1745–1829)" curriculum unit for advanced students from Bill of Rights Institute

- John Jay, Supreme Court Historical Society

- Oyez Project U.S. Supreme Court media on John Jay.

- Works by John Jay at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Jay at the Internet Archive

- Works by John Jay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- John Jay at MetaLibri

- John Jay bust, by John Frazee (1790–1852), Marble, circa 1831, Size: 24" h., Catalog No. 21.00010, S-141, Old Supreme Court Chamber, U.S. Senate Collection, Office of Senate Curator.

- Essay: John Jay and the Constitution Online exhibition for Constitution Day 2005, based on the notes of Professor Richard B. Morris (1904–1989) and his staff, originally prepared for volume 3 of the Papers of John Jay.

- The Papers of John Jay An image database and indexing tool comprising some 13,000 documents scanned chiefly from photocopies of original documents from the Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York and approximately 90 other institutions.

- John Jay

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- 1745 births

- 1829 deaths

- Abolitionists from New York City

- American Bible Society

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of French descent

- American slave owners

- Chief justices of the United States

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- Candidates in the 1788–1789 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1796 United States presidential election

- Continental Congressmen from New York (state)

- Federalist Party state governors of the United States

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Governors of New York (state)

- Huguenot participants in the American Revolution

- Jay family

- Members of the American Antiquarian Society

- New York (state) Federalists

- New York (state) lawyers

- People from Bedford, New York

- People from Katonah, New York

- People from Rye, New York

- The Federalist Papers

- United States secretaries of state

- 1800 United States vice-presidential candidates

- Washington administration cabinet members

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- Van Cortlandt family

- Patriots in the American Revolution

- People from colonial New York

- United States secretary of foreign affairs

- Signers of the Continental Association

- United States federal judges appointed by George Washington

- 18th-century American diplomats

- 18th-century American politicians

- 18th-century American judges

- 19th-century American politicians