Janet Lynn

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2024) |

| Janet Lynn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

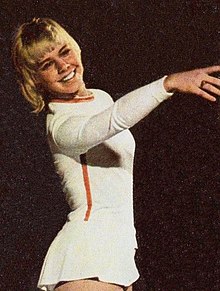

Janet Lynn c. 1972 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | April 6, 1953 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 5 ft 2 in (157 cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure skating career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skating club | Wagon Wheel Figure Skating Club[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Retired | 1975 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Janet Lynn Nowicki (born April 6, 1953) is an American figure skater. She is the 1972 Olympic bronze medalist, a two-time world championships medalist, and a five-time senior Ladies U.S. national champion.[1]

Amateur career

[edit]

Lynn began to skate almost as soon as she could walk, and took part in her first exhibition performance at the age of four at Chicago Stadium. By age seven, she was living away from home part of the year, staying with the slightly older skater Kathleen Kranich to be close to her coach Slavka Kohout, who worked out of Rockton, Illinois, but her close-knit family was never far away. Eventually her family moved from the Chicago suburb of Evergreen Park to Rockford, Illinois, some fifteen miles from Rockton and the rink. Janet attended Lincoln Junior High in Rockford. She used her middle name Lynn instead of Nowicki, which was constantly being misspelled and mispronounced. Janet was always forthright about the name change; in her own mind her name was still Nowicki.

In 1964, at 11, she became the youngest skater to pass the rigorous eighth and final test administered by the United States Figure Skating Association, and two years later she won the U.S. Junior Ladies Championship at Berkeley, California. At that competition she landed a triple salchow jump, which at the time was rarely performed by female skaters. In later years she was also one of the first female skaters to include a triple toe loop in her programs.

Moving up to the senior level, Lynn won bronze at the 1968 U.S. Championships, which qualified her to compete at the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France, where she placed 9th. At the time she was 14 years old and it was her first major international competition. She also placed 9th at her first World Championships in 1968.

Lynn won her first senior national title at the 1969 U.S. Figure Skating Championships. That year she beat Canada's Karen Magnussen for the North American Championship. She then finished 5th at the World Championships despite the absence of both Magnussen and Czechoslovakia's Hana Mašková due to injuries. She fell behind Julie Lynn Holmes, whom she had beaten for the national title, while Gabriele Seyfert of East Germany took the gold medal. At the 1970 World Championships, Seyfert and Austria's Trixi Schuba were again in 1st and 2nd place, while Holmes moved up to 3rd and Lynn finished in 6th. Part of the problem was an inconsistency in compulsory figures, which meant that she always had to make up ground in the free skating. Lynn made an effort to remedy this weakness by working with the great New York-based coach Pierre Brunet, who had previously had World Champions Carol Heiss and Donald Jackson under his tutelage. At the 1971 World Championships, she placed 5th in figures and skated well in the free skating to place 4th overall, while Schuba took the gold, Holmes the silver and Magnussen the bronze.

In 1972, Lynn beat Holmes for the national title for the fourth year in a row, and there were widespread predictions that she would take World and Olympic gold, especially because of Schuba's weakness in free skating. Schuba's lackluster performance at Lyon, France the previous year had even drawn boos, but she won the championship based on her enormous lead in the compulsory figures. At the 1972 Winter Olympics at Sapporo, Hokkaidō, Japan, Lynn placed 4th in the compulsory figures while Schuba established a large lead in the segment. Although Schuba placed 7th in the free skating, her lead in figures enabled her to take the gold medal, while Magnussen won the silver and Lynn took the bronze, an order of finish repeated at the 1972 World Championships in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.[1]

By this time, Lynn's motivation was decreasing and she also struggled with her weight, leading her to consider leaving competition. She decided to continue competing and took her fifth National title in 1973. With Schuba's retirement and the devaluation of compulsory figures caused by the addition of the short program to competitions, only Magnussen seemed to stand in her way. At the 1973 World Championships, Lynn skated her best figures ever, taking 2nd in that discipline, but in the newly introduced short program of required jumps and spins, which she had been expected to win, two falls landed her in 12th position. She won the free skate and moved up to take the silver medal in the final event of her amateur career.

Professional career

[edit]Lynn's popularity was such that the Ice Follies offered her a three-year contract for $1,455,000, which made her the highest-paid female professional athlete of the time. Ice Follies with Lynn as its star positioned itself on a firmer basis in its rivalry with the Ice Capades. In 1974, Janet Lynn became the World Professional Champion in an event created by promoter Dick Button to showcase her.

Lynn's professional career was cut short after only two years by problems with allergy-related asthma exacerbated by the cold, damp air in skating rinks. In 1975, she retired from skating and started a family. In the early 1980s, with her asthma under control, she returned to skate professionally for a few years. She again appeared in Button's professional competitions and co-starred with John Curry in his made-for-TV ice ballet, "The Snow Queen".[1]

Legacy

[edit]The contrast between Lynn and Trixi Schuba was one of the reasons why the International Skating Union devalued the weight of compulsory figures in competition by introducing the short program.[2] Since compulsory figures were rarely televised and were not well understood by the general public, television audiences were confused and angry when skaters such as Lynn, who excelled in the free skate, consistently lost competitions to skaters such as Schuba, who were not as strong in the free skate.

Lynn was known as one of figure skating's early pioneers of women's triple jumps, but she was also well known for her "musical expressiveness, graceful movement, and the almost ethereal quality of her skating".[3] She has also been credited with the introduction of the short program in singles skating, the increase in the value of the free skating program, and the eventual devaluing of compulsive figures.[3] According to figure skating writing and historian Ellyn Kestnbaum, Lynn, along with her contemporary Dorothy Hamill, "evoked associations with natural, outdoorsy wholesomeness" due to their athleticism, speed, freedom of movement, and appearance, which Kestnbaum states were "images that resonated with both conservative and feminist ideologies during the 1970s"[3] Lynn was called "a peerless artist",[3] a skater known for both her artistry and athleticism, although as Kestnbaum states, Lynn's performances seemed to be more of an expression of who she was as a person than a carefully crafted work of art.[3]

Results

[edit]| Event | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Olympics | 9th | 3rd | |||||||

| World Championships | 9th | 5th | 6th | 4th | 3rd | 2nd | |||

| North American Championships | 1st | 2nd | |||||||

| U.S. Championships | 8th J. | 4th | 3rd | 1st | 1st | 1st | 1st | 1st |

See also

[edit]- V sign (her fame in Japan, and the possible origin there of the V sign in casual photos)[citation needed]

- Figure skating

- 1972 Winter Olympics

- U.S. Figure Skating Championships

- World Figure Skating Championships

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Janet Lynn | Bio, Stats, and Results". www.sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020.

- ^ Hines, James R., "Figure Skating. A History", University of Illinois Press, 2006, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d e Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middleton, Connecticut: Wesleyan Publishing Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8195-6641-1.

Bibliography

[edit]- Janet Lynn. Peace + Love. ISBN 0-88419-069-2.

- Janet Lynn Salomon. Family, Faith, and Freedom

- Christine Brennan. Inside Edge: A Revealing Journey into the Secret World of Figure Skating. Anchor Books, 1997. ISBN 0-385-48607-3.

- 1953 births

- Living people

- American female single skaters

- Figure skaters at the 1968 Winter Olympics

- Figure skaters at the 1972 Winter Olympics

- Olympic bronze medalists for the United States in figure skating

- Sportspeople from Rockford, Illinois

- American Christians

- Olympic medalists in figure skating

- World Figure Skating Championships medalists

- Medalists at the 1972 Winter Olympics

- People from Evergreen Park, Illinois

- American people of Polish descent

- 20th-century American sportswomen