John Roberts

John Roberts | |

|---|---|

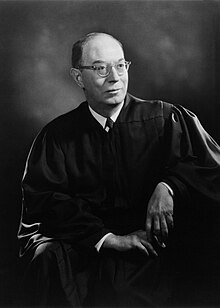

Official portrait, 2005 | |

| 17th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| Assumed office September 29, 2005 | |

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | William Rehnquist |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office June 2, 2003 – September 29, 2005 | |

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | James L. Buckley |

| Succeeded by | Patricia Millett |

| Principal Deputy Solicitor General of the United States | |

| In office October 24, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Donald B. Ayer |

| Succeeded by | Paul Bender |

| Associate Counsel to the President | |

| In office November 28, 1982 – April 11, 1986 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | J. Michael Luttig[1] |

| Succeeded by | Robert Kruger[2] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Glover Roberts Jr. January 27, 1955 Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Jane Sullivan (m. 1996) |

| Children | 2 (adopted) |

| Education | Harvard University (BA, JD) |

| Awards | Henry J. Friendly Medal (2023) |

| Signature | |

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American jurist serving since 2005 as the 17th chief justice of the United States. He has been described as having a moderate conservative judicial philosophy, though he is primarily an institutionalist.[3][4] Regarded as a swing vote in some cases,[5] Roberts has presided over an ideological shift toward conservative jurisprudence on the high court, in which he has authored key opinions.[6][7]

Born in Buffalo, New York, Roberts was raised Catholic in Northwest Indiana and studied at Harvard University with the initial intent to become a historian, graduating in three years with highest distinction, then attended Harvard Law School, where he was an editor of the Harvard Law Review. Before holding positions in the Reagan and senior Bush administration, Roberts served as a law clerk for Judge Henry Friendly and Justice William Rehnquist. From 1989 to 1993, he was Principal Deputy Solicitor General, after which he built a leading appellate practice and argued 39 cases before the Supreme Court.[8]

In 1992, President George H. W. Bush nominated Roberts to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, but the Senate did not hold a vote on his confirmation. In 2003, President George W. Bush appointed Roberts to the D.C. Circuit. In 2005, Bush nominated Roberts to the Supreme Court, initially as an associate justice to fill the vacancy left by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, but promoted him to chief justice after Rehnquist's death. Roberts was confirmed by a Senate vote of 78–22, becoming the youngest to serve in the position since John Marshall.[9]

As chief justice, Roberts has authored majority opinions in many landmark cases, including National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (upholding most sections of the Affordable Care Act), Shelby County v. Holder (limiting the Voting Rights Act of 1965), Trump v. Hawaii (expanding presidential powers over immigration), Carpenter v. United States (expanding digital privacy), Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (overruling race-based admission programs), and Trump v. United States (outlining the extent of presidential immunity from criminal prosecution). Roberts also presided over the first impeachment trial of President Donald Trump.

Early life and education

Roberts was born on January 27, 1955, in Buffalo, New York, to Rosemary (née Podrasky) and John Glover "Jack" Roberts Sr., both devout Catholics.[10] His father had Irish and Welsh ancestry and his mother was a descendant of Slovak immigrants from Szepes, Hungary.[11] He has two younger sisters, Margaret and Barbara, and an elder sister, Kathy.[12] Roberts spent his early childhood years in Hamburg, New York, where his father worked as an electrical engineer for the Bethlehem Steel Corporation's factory in Lackawanna.[13]

In 1965, ten-year-old Roberts and his family moved to Long Beach, Indiana, where his father became the manager of a new steel plant in nearby Burns Harbor.[14] By age 13, Roberts "already had a clear plan for his life."[15] He attended the parochial La Lumiere School,[16] an academically rigorous Catholic boarding school in La Porte, Indiana,[17] where he captained the school's football team, participated in track and field, and was a regional champion in wrestling. He also participated in choir and drama, and was a co-editor of the school newspaper.[14] He graduated in 1973 as class valedictorian, becoming the first graduate of the La Lumiere School to enroll at Harvard University.[18]

At Harvard College, Roberts dedicated himself to studying history, his academic major. He had entered Harvard as a sophomore with second-year standing based on his academic achievements in high school.[19] Roberts first roomed in Straus Hall before moving to Leverett House.[20] Every summer, he returned home to work at the steel plant his father managed.[14] Although he initially felt obscured among other students, Roberts distinguished himself with professors, meriting multiple distinctions for his scholarly writing.[21] He gained a reputation as a serious student who valued formalism.[20] Every Sunday, he attended Catholic Mass at St. Paul Church.[22]

Roberts focused on modern European history and maintained an interest in politics.[23] As an undergraduate, he excelled academically.[14] In his first year, he won the university's Edwards Whitaker Scholarship for outstanding scholastic achievement.[21] He intended to pursue a Ph.D. in history to be a professor but also contemplated a legal career.[24] One of Roberts's first papers, "Marxism and Bolshevism: Theory and Practice," won Harvard's William Scott Ferguson Prize for the most outstanding essay by a sophomore history major.[21] An early interest in oral advocacy led him to study Daniel Webster, a prominent advocate before the Supreme Court.[25] His senior year paper, "The Utopian Conservative: A Study of Continuity and Change in the Thought of Daniel Webster," won a Bowdoin Prize.[26]

In 1976, Roberts obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree in history, summa cum laude, with membership in Phi Beta Kappa. A recent surplus of history graduate students convinced him to attend Harvard Law School for better career prospects, though he maintained his original goal to become a professor.[27][a] His first-year performance in law school placed him in the top 15 students in a class of 550 and won him membership of the Harvard Law Review.[28] The journal's president, David Leebron, chose Roberts as its managing editor, despite their differing political views.[27][b] Classmate David Wilkins described Roberts as "more conservative than the typical Harvard Law student in the 1970s" but well-liked by fellow students.[20] In 1979, Roberts graduated at the top of his class with a Juris Doctor, magna cum laude, despite having to admit himself to a local hospital for exhaustion. He later regretted that during his time at Harvard, he traveled into Boston on only a couple of occasions, being too preoccupied with his studies.[30]

Early legal career

After graduating from law school, Roberts was a law clerk for Judge Henry Friendly,[c] one of the most influential judges of the century, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979 to 1980.[32] Friendly was impressed by Roberts's performance; they shared similar backgrounds,[33] and co-clerk Reinier Kraakman recalled that "there was a bond between them."[34] When Roberts became a federal judge years later, he identified with Friendly's nonpartisan approach to law and maintained a correspondence with him.[35][d] After finishing his clerkship at the Second Circuit in May,[34] Roberts went to clerk for Justice (later Chief Justice) William Rehnquist at the U.S. Supreme Court from 1980 to 1981.[14]

At the end of his clerkship with Rehnquist, Roberts worked to gain admission to the bar, studying with Michael W. McConnell, a law clerk of Justice William Brennan. After the 1980 presidential election, he resolved to work under the new Reagan administration.[37] Rehnquist recommended him to Ken Starr, who was chief of staff to attorney general William French Smith, and Roberts was named a special assistant to the attorney general. After being admitted to the District of Columbia bar and arriving to the Department of Justice in August 1981, he helped Sandra Day O'Connor prepare for her confirmation hearings.[38][e]

As an assistant to the attorney general, Roberts concentrated on the scope of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, especially Section 2 and Section 5, both of which Roberts and other Reagan lawyers believed to have unnecessarily intruded on state regulations.[40] He wrote to Friendly, "this is an exciting time to be at the Justice Department, when so much that has been taken for granted for so long is being seriously reconsidered."[41] Among those he worked with were William Bradford Reynolds in the Civil Rights Division, former classmate Richard Lazarus, J. Harvie Wilkinson III, Theodore Olson, and fellow special assistant Carolyn Kuhl.[42]

In 1982, Reagan advisor Fred Fielding recruited Roberts to work at the White House. Fielding gathered a group of lawyers that also included J. Michael Luttig and Henry Garrett.[43] From 1982 to 1986, Roberts was an associate with the White House Counsel.[14] He then entered private practice in Washington, D.C., as an associate at the law firm Hogan & Hartson (now Hogan Lovells), working in corporate law.[44] E. Barrett Prettyman, under whom he was first assigned, was one of the most prominent advocates in the country along with Rex E. Lee.[45] Roberts also built a successful practice as an appellate lawyer,[16] heading the firm's division for appellate advocacy.[46] He made his first appearance before the Supreme Court in United States v. Halper, arguing against the government, and the Court unanimously upheld his arguments.[47]

Appellate advocacy

In 1989, Ken Starr relinquished his judgeship on the D.C. Circuit to become U.S. Solicitor General under President George H. W. Bush. Needing a deputy, Starr chose Roberts to join the administration as Principal Deputy Solicitor General.[48][49] "I felt that his experience was good for the political deputy position. [Roberts] was a steady hand, a wise hand. He came in as a person not of vast experience but of vast ability," Starr recalled.[50] With the new appointment, Roberts, whose work had previously been confidential, became a prominent figure at the Supreme Court, leading the filings of the Bush administration and representing it in the media.[51]

As deputy solicitor general, Roberts frequently appeared before the Supreme Court.[52] He argued for a number of conservative positions, including those against abortion, an extensive federal jurisdiction and policies that afforded special benefits to minority groups.[53] In 1990, he successfully argued his first case in Atlantic Richfield Company v. USA Petroleum Company, which concerned anti-trust law, and then successfully argued the standing case of Lujan v. National Wildlife Federation, which became a hallmark in the field.[54] When Starr recused himself in Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, Roberts took his place, arguing that the use of racial preferences by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was unconstitutional. The position failed to convince the Court, which announced on June 27, 1990, that it had sided with the FCC. Government attorneys, surprised by Roberts's stance against the FCC, discussed whether it contributed to a politicization of the office, as the Solicitor General traditionally defended the government.[55] Thomas Merrill, a deputy for the Solicitor General, described Roberts's candid position simply as: "This affirmative action program violated the Constitution, and we should present that to the Supreme Court."[56]

When Clarence Thomas was confirmed to the Supreme Court in 1991, Roberts's proven experience in complex litigation for the Bush administration made him a leading candidate to fill Thomas's vacancy on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.[58] On January 27, 1992, Bush nominated Roberts, who had just turned 37 years old, to the D.C. Circuit, and Starr urged Senator Joe Biden, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, to schedule a hearing despite an upcoming election year. Democratic lobbyists and progressive interest groups successfully encouraged Biden to stall the process.[59] As Bill Clinton defeated Bush in the 1992 presidential election, Roberts's nomination lapsed with no Senate vote and expired at the end of the 102nd Congress.[60][61]

In January 1993, Roberts returned to Hogan and Hartson, where, finding great success as an advocate, he began to regularly appear again before the Supreme Court.[62] With a reputation as the leading private Supreme Court litigator, Roberts often represented corporations that sued individuals or the government. He was Hogan and Hartson's most prominent partner, arguing 18 Supreme Court cases from 1993 to 2003 and 20 in nationwide appellate courts while also doing work pro bono, demonstrating expertise in a wide variety of different fields.[63][64]

In June 1995, to Roberts's satisfaction, the Supreme Court overruled his previous loss of Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC in Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña, establishing that the government must treat people on an individual basis.[65] The next year, his pro bono contributions included giving fundamental aid to gay rights activists in the landmark case of Romer v. Evans (1996).[66] During the 2000 presidential election, Roberts went to Florida to assist George W. Bush,[67] by which time Jeffrey Toobin identified him as "among the top advocates of his generation".[68] According to biographer Joan Biskupic, he built a reputation "for his powers of persuasion and tireless preparation", and "his meticulous preparation and unflagging composure inspired confidence among his well-heeled clients."[69] His arguments against government regulation often appealed to Rehnquist and the Court's conservatives while his style and skill in rhetoric won him the respect of John Paul Stevens and the Court's liberals.[70] Democrats and Republicans alike widely viewed Roberts as one of the Supreme Court's most distinguished advocates.[71]

| Case | Argued | Decided | Represented |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Options v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938 | March 22, 1995 | May 22, 1995 | Respondent |

| Adams v. Robertson, 520 U.S. 83[permanent dead link] | January 14, 1997 | March 3, 1997 | Respondent |

| Alaska v. Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government, 522 U.S. 520 | December 10, 1997 | February 25, 1999 | Petitioner |

| Feltner v. Columbia Pictures Television, Inc., 523 U.S. 340 | January 21, 1998 | March 31, 1998 | Petitioner |

| National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Smith, 525 U.S. 459 | January 20, 1999 | February 23, 1999 | Petitioner |

| Rice v. Cayetano, 528 U.S. 495 | October 6, 1999 | February 23, 2000 | Respondent |

| Eastern Associated Coal Corp. v. Mine Workers, 531 U.S. 57 | October 2, 2000 | November 28, 2000 | Petitioner |

| TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23 | November 29, 2000 | March 20, 2001 | Petitioner |

| Toyota Motor Manufacturing v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184 | November 7, 2001 | January 8, 2002 | Petitioner |

| Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 535 U.S. 302 | January 7, 2002 | April 23, 2002 | Respondent |

| Rush Prudential HMO, Inc. v. Moran, 536 U.S. 355 | January 16, 2002 | June 20, 2002 | Petitioner |

| Gonzaga University v. Doe, 536 U.S. 273 | April 24, 2002 | June 20, 2002 | Petitioner |

| Barnhart v. Peabody Coal Co., 537 U.S. 149 | October 8, 2002 | January 15, 2003 | Respondent |

| Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 | November 13, 2002 | March 5, 2003 | Petitioner |

U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

When George W. Bush won the contested 2000 presidential election, journalists speculated about whom he might consider as possible nominees for the Supreme Court.[72] Luttig, Wilkinson, and other Reagan officials were leading candidates, but Judge Alberto Gonzales of the Texas Supreme Court, a close supporter of Bush, also emerged and had a chance to be the first Latino nominee.[73] Roberts, who had not worked in government while Bill Clinton was in office, did not appear on lists compiled by Bush supporters, advocacy groups, or the media, but nonetheless remained a strong candidate for a Republican nomination and was poised to be re-nominated to the D.C. Circuit, often used as a platform for Supreme Court nomination.[74]

On May 9, 2001, Bush nominated Roberts to a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to replace Judge James L. Buckley, who had retired.[75] Unlike in 1992 when his first nomination stalled in the Democratic-majority Senate, Roberts's nomination came when Republicans had secured a one-vote Senate majority. But it soon lost that majority when Senator Jim Jeffords left the party to become an independent, jeopardizing Roberts's candidacy, which stalled once again when Senate Democrats refused to hold any nomination hearings.[76] In 2002, Republicans regained control of the Senate and Roberts finally received a hearing by the Senate Judiciary Committee.[77]

Supported by a bipartisan letter of support signed by more than 150 members of the District of Columbia Bar—including White House counsels Lloyd Cutler, C. Boyden Gray, and Solicitor General Seth Waxman—the Judiciary Committee recommended Roberts by a vote of 16 to 3,[f] and the Senate confirmed him unanimously by voice vote on May 8, 2003.[79] On June 2, he received his judicial commission.[80] Even when Roberts had not yet fully assumed his role as a circuit judge, White House Counsel officers listed him on their shortlist of Supreme Court candidates.[81]

Roberts authored 49 opinions during his two-year service on the D.C. Circuit, many of which concerned decisions by the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.[82] His opinions often employed a "characteristically crisp, clear writing style" that favored the use of imagery and idioms.[83][g] Most of the disputes he reviewed concerned government regulation, union rights, and collective bargaining,[83] but he also wrote on environmental law,[h] criminal law,[i] and procedural matters.[85] One case, Hedgepeth ex rel Hedgepeth v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit (2004), garnered media attention when Roberts found that Washington police properly detained a 12-year-old girl who ate in violation of a zero tolerance policy against eating in a metro station.[84] His opinions generally reflected a conservative judicial philosophy, including in areas of civil rights and executive power.[86] The brevity of his tenure and his cautiousness in deciding cases left little for potential opponents to scrutinize while he made rulings as a circuit judge.[87]

Nomination to the Supreme Court of the United States (2005)

By the time of the 2004 presidential election, Justice Rehnquist had been fatally ill and senior Bush administration advisors under Karl Rove began assessing the potential candidates to replace him. Among them, Roberts stood out for his experience as a Supreme Court advocate, which had brought him the favorable attention of not just conservatives but also liberals such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[88]

On July 19, 2005, President Bush nominated Roberts to the U.S. Supreme Court to fill a vacancy to be created by the impending retirement of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. Roberts's nomination was the first Supreme Court nomination since Stephen Breyer's in 1994. On September 3, 2005, while Roberts's confirmation was pending before the Senate, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist died. Two days later, Bush withdrew Roberts's nomination as O'Connor's successor and nominated Roberts to succeed Rehnquist as chief justice.[89]

Roberts's testimony on his jurisprudence

During his confirmation hearings, Roberts said he did not have a comprehensive jurisprudential philosophy and did "not think beginning with an all-encompassing approach to constitutional interpretation is the best way to faithfully construe the document."[90][91] Roberts compared judges to baseball umpires: "[I]t's my job to call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat."[92] Among the issues he discussed during the hearings were:

Commerce Clause

In Senate hearings, Roberts said:

Starting with McCulloch v. Maryland, Chief Justice John Marshall gave a very broad and expansive reading to the powers of the federal government and explained generally that if the ends be legitimate, then any means chosen to achieve them are within the power of the federal government, and cases interpreting that, throughout the years, have come down. Certainly, by the time Lopez was decided, many of us had learned in law school that it was just sort of a formality to say that interstate commerce was affected and that cases weren't going to be thrown out that way. Lopez certainly breathed new life into the Commerce Clause. I think it remains to be seen, in subsequent decisions, how rigorous a showing, and in many cases, it is just a showing. It's not a question of an abstract fact—does this affect interstate commerce or not—but has this body, the Congress, demonstrated the impact on interstate commerce that drove them to legislate? That's a very important factor. It wasn't present in Lopez at all. I think the members of Congress had heard the same thing I had heard in law school, that this is unimportant—and they hadn't gone through the process of establishing a record in that case.[91]

Federalism

Roberts said the following about federalism in a 1999 radio interview:

We have gotten to the point these days where we think the only way we can show we're serious about a problem is if we pass a federal law, whether it is the Violence Against Women Act or anything else. The fact of the matter is conditions are different in different states, and state laws can be more—relevant is I think exactly the right term, more attuned to the different situations in New York, as opposed to Minnesota, and that is what the federal system is based on.[93]

Reviewing Acts of Congress

At a Senate hearing, Roberts said:

The Supreme Court has, throughout its history, on many occasions described the deference that is due to legislative judgments. Justice Holmes described assessing the constitutionality of an act of Congress as the gravest duty that the Supreme Court is called upon to perform. ... It's a principle that is easily stated and needs to be observed in practice, as well as in theory. Now, the Court, of course, has the obligation, and has been recognized since Marbury v. Madison, to assess the constitutionality of acts of Congress, and when those acts are challenged, it is the obligation of the Court to say what the law is. The determination of when deference to legislative policy judgments goes too far and becomes abdication of the judicial responsibility, and when scrutiny of those judgments goes too far on the part of the judges and becomes what I think is properly called judicial activism—that is certainly the central dilemma of having an unelected, as you describe it correctly, undemocratic judiciary in a democratic republic.[91]

Stare decisis

On the subject of stare decisis, referring to Brown v. Board of Education, the decision overturning school segregation, Roberts said: "the Court in that case, of course, overruled a prior decision. I don't think that constitutes judicial activism because obviously if the decision is wrong, it should be overruled. That's not activism. That's applying the law correctly."[94]

Roe v. Wade

As a lawyer for the Reagan administration, Roberts wrote legal memos defending administration policies on abortion.[95] At his nomination hearing, he testified that the legal memos represented the views of the administration he was representing at the time and not necessarily his own.[96] "I was a staff lawyer; I didn't have a position," Roberts said.[96] As a lawyer in the George H. W. Bush administration, Roberts signed a legal brief urging the court to overturn Roe v. Wade.[97]

In private meetings with senators before his confirmation, Roberts testified that Roe was settled law, but added that it was subject to the legal principle of stare decisis,[98] meaning that while the Court must give some weight to the precedent, it was not legally bound to uphold it.

In his Senate testimony, Roberts said that, while sitting on the Appellate Court, he had an obligation to respect precedents established by the Supreme Court, including the right to abortion. He said: "Roe v. Wade is the settled law of the land. ... There is nothing in my personal views that would prevent me from fully and faithfully applying that precedent, as well as Casey." Following nominees' traditional reluctance to indicate which way they might vote on an issue likely to come before the Supreme Court, he did not explicitly say whether he would vote to overturn either.[90] Jeffrey Rosen said, "I wouldn't bet on Chief Justice Roberts's siding unequivocally with the anti-Roe forces."[99]

Confirmation

On September 22, 2005, the Senate Judiciary Committee approved Roberts's nomination by a vote of 13–5, with Senators Ted Kennedy, Richard Durbin, Charles Schumer, Joe Biden, and Dianne Feinstein opposed. The full Senate confirmed Roberts on September 29 by a margin of 78–22.[100] All Republicans and the one Independent voted for Roberts; the Democrats split evenly, 22–22. Roberts was confirmed by what was, historically, a narrow margin for a Supreme Court justice,[9] but all subsequent confirmation votes have been even narrower.[101][102][103][104]

U.S. Supreme Court

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Roberts took the Constitutional oath of office, administered by Associate Justice John Paul Stevens at the White House, on September 29, 2005. On October 3, he took the judicial oath provided for by the Judiciary Act of 1789 at the United States Supreme Court building.

Justice Antonin Scalia said that Roberts "pretty much run[s] the show the same way" as Rehnquist, albeit "let[ting] people go on a little longer at conference ... but [he'll] get over that."[105] Analysts such as Jeffrey Toobin have portrayed Roberts as a consistent advocate for conservative principles.[106] Garrett Epps called Roberts's prose "crystalline, vivid, and often humorous."[107]

Seventh Circuit judge Diane Sykes, surveying Roberts's first term on the Court, concluded that his jurisprudence "appears to be strongly rooted in the discipline of traditional legal method, evincing a fidelity to text, structure, history, and the constitutional hierarchy. He exhibits the restraint that flows from the careful application of established decisional rules and the practice of reasoning from the case law. He appears to place great stock in the process-oriented tools and doctrinal rules that guard against the aggregation of judicial power and keep judicial discretion in check: jurisdictional limits, structural federalism, textualism, and the procedural rules that govern the scope of judicial review."[108] Roberts has been said to operate under an approach of judicial minimalism in his decisions,[109] having said, "[i]f it is not necessary to decide more to a case, then in my view it is necessary not to decide more to a case."[110] His decision-making and leadership seems to demonstrate an intention to preserve the Court's power and legitimacy while maintaining judicial independence.[111]

In November 2018, the Associated Press approached Roberts for comment after President Donald Trump called a jurist who ruled against his asylum policy an "Obama judge." Roberts responded: "[w]e do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them." His remarks were widely interpreted as a rebuke of Trump's comment.[112][113][114] As chief justice, Roberts presided over the first impeachment trial of Donald Trump, which began on January 16 and ended on February 5, 2020.[115] Roberts did not preside over Trump's second impeachment trial, believing that the Constitution requires only that the chief justice preside in the trial of a sitting president, not of a former president.[116]

Although Roberts's judicial philosophy is considered conservative, he is seen as having a more moderate orientation than his predecessor, William Rehnquist, particularly when Bush v. Gore is compared to Roberts's vote for the ACA: his vote in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius to uphold the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) caused the press to contrast his Court with the Rehnquist Court.[117] Roberts's judicial philosophy is also seen as more moderate and conciliatory than Antonin Scalia's or Clarence Thomas's.[118][119][117] He seems to want more consensus from the Court.[118] At the beginning of his tenure, Roberts's voting pattern closely aligned with Samuel Alito's,[120] but in recent years, his voting pattern has resembled Brett Kavanaugh's, who is generally seen as far more moderate than Alito.[121]

After the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, several commentators wrote that Roberts was no longer the leading justice. As the five other conservative justices could outvote the rest, he supposedly could no longer preside over a moderately conservative course while respecting precedent.[122][123] This view was espoused again after the 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe and Casey.[124][125]

Presidential power

On June 26, 2018, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, upholding the Trump administration's travel ban against seven nations, five of which had a Muslim majority.[126] In his opinion, Roberts concluded that 8 U. S. C. §1182(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act gives the president broad authority to suspend the entry of non-citizens into the country and that Presidential Proclamation 9645 did not exceed the limitations of said act.[127] Additionally, Roberts wrote that the proclamation and its travel ban did not violate the Free Exercise Clause, as Trump's statements in support of the ban could be justified on the basis of national security.[128][129]

On July 9, 2020, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Trump v. Vance, regarding presidential immunity from criminal subpoenas relating to the president's personal information.[130] In doing so, he rejected arguments relating to the investiture of absolute immunity in either the Supremacy Clause or Article II of the Constitution or of presidential entitlement to a higher standard of issuance of a subpoena.[131][132] Roberts emphasized this point, writing, "In our judicial system, 'the public has a right to every man's evidence'. Since the earliest days of the Republic, 'every man' has included the President of the United States."[133]

On July 9, 2020, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP, regarding the authority of congressional subpoenas relating to certain personal information relating to the president.[134] In his opinion, Roberts recognized the role of executive privilege in presidential decision-making but contended that executive privilege did not preclude blanket immunity from records requests, as protection caused by executive privilege "should not be transplanted root and branch to cases involving nonprivileged, private information, which by definition does not implicate sensitive Executive Branch deliberations."[135]

On July 1, 2024, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Trump v. United States, writing that a president has absolute immunity for acts committed as president within their constitutional purview, presumptive immunity for official acts, and no immunity for unofficial acts.[136][137] In his opinion, Roberts notes the importance of balancing fair and effective enforcement of criminal laws, alongside the effects criminal charges for a president's official acts may have in hampering a president's decision-making while in office.[138] Presumptive immunity for such official acts is therefore necessary "to ensure that the President can undertake his constitutionally designated functions effectively, free from undue pressure or distortions", but such a presumption can be overcome provided an assertion of criminality that "pose[s] no dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch."[139] In determining whether a potentially criminal action is official, neither a violation of law nor a president's motives in acting on said violation may be used in determining it as such.[140][141] In addition, in charging a president for crimes relating to unofficial acts, evidence involving official acts may not be used, as such usage would threaten "to eviscerate the immunity [...] recognized. It would permit a prosecutor to do indirectly what he cannot do directly—invite the jury to examine acts for which a President is immune from prosecution to nonetheless prove his liability on any charge."[142][143]

Campaign finance

Roberts wrote the opinion in the 2007 decision FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc., which held that provisions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 that limited political advertising were unconstitutional as applied to WRTL's issue ads preceding the election.[144] Roberts and Justice Alito declined to revisit the Court's 2003 decision in McConnell v. FEC at that time.[145]

In 2010, Roberts joined the opinion of the Court in Citizens United v. FEC, which struck down provisions of BCRA that restricted unions, corporations, and profitable organizations from independent political spending and prohibited the broadcasting of political media funded by them within 60 days of general elections or 30 days of primary elections. Roberts wrote his own concurring opinion "to address the important principles of judicial restraint and stare decisis implicated in this case".[146]

Roberts wrote the plurality opinion in the 2014 landmark campaign finance case McCutcheon v. FEC, which held that "aggregate limits" on the combined amount a donor may give to various federal candidates or party committees violate the First Amendment.[107][147]

In 2015, Roberts joined the liberal justices in Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar, holding that the First Amendment does not prohibit states from barring judges and judicial candidates from personally soliciting funds for their election campaigns.[148] For the majority, Roberts wrote that such a rule is narrowly tailored to serve the compelling interest of keeping the judiciary impartial.[149]

In 2021, the Supreme Court decided Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, which held that California's requirement that nonprofit organizations disclose the identity of their donors to the state's Attorney General as a precondition of soliciting donations in the state violates the First Amendment. For the majority, Roberts wrote, "California casts a dragnet for sensitive donor information from tens of thousands of charities each year, even though that information will become relevant in only a small number of cases involving filed complaints."[150] It therefore does not serve a narrowly tailored government interest and thus is invalid.

Fourth Amendment

Roberts wrote his first dissent in Georgia v. Randolph (2006). The majority's decision prohibited police from searching a home if both occupants are present, one objects, and the other consents. Roberts criticized the decision as inconsistent with prior case law and for partly basing its reasoning on its perception of social custom. He said the social expectation test was flawed because the Fourth Amendment protects a legitimate expectation of privacy, not social expectations.[151]

In Utah v. Strieff (2016), Roberts joined the five-justice majority in ruling that a person with an outstanding warrant may be arrested and searched and that any evidence discovered in that search is admissible in court; the majority held that this remains true even when police act unlawfully by stopping a person without reasonable suspicion, before learning of the existence of the outstanding warrant.[152]

In Carpenter v. United States (2018), a landmark decision involving privacy of cellular phone data, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in a 5–4 ruling that searches of cellular phone data generally require a warrant.[153]

Abortion

In Gonzales v. Carhart (2007), Roberts voted with the majority to uphold the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act. Kennedy, writing for a five-justice majority, distinguished Stenberg v. Carhart, and concluded that the Court's previous decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey did not prevent Congress from banning the procedure. The decision left the door open for future as-applied challenges, and did not address the broader question of whether Congress had the authority to pass the law.[154] Thomas filed a concurring opinion contending that Roe v. Wade and Casey should be reversed; Roberts did not join that opinion.

In 2018, Roberts and Kavanaugh joined four more liberal justices in declining to hear a case brought by Louisiana and Kansas to deny Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood,[155] thereby letting stand lower court rulings in Planned Parenthood's favor.[156] Roberts also joined with liberal justices in 5–4 decisions temporarily blocking a Louisiana abortion restriction (2019)[157] and later striking down that law (June Medical Services, LLC v. Russo (2020)).[158][159] The law at issue in June was similar to one the court struck down in Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), which Roberts had voted to uphold;[160][161] in his June opinion, Roberts wrote that while he believed Whole Woman's Health was wrongly decided he was joining the majority in June out of respect for stare decisis.[160] It was the first time in his 15 years on the Supreme Court that Roberts had cast a vote to invalidate a law that regulated abortion.[162] In September 2021, the Supreme Court declined an emergency petition to temporarily block enforcement of the Texas Heartbeat Act, which bans abortion after six weeks of pregnancy except to save the mother's life. Roberts, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan were in the minority.[163] In 2022, Roberts declined to join the majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. He wrote a concurring opinion supporting only the decision to uphold the Mississippi abortion statute, stating that the right to an abortion should "extend far enough to ensure a reasonable opportunity to choose, but need not extend any further." Roberts also declined to join the dissenting opinion by Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.

Capital punishment

On November 4, 2016, Roberts was the deciding vote in a 5–3 decision to stay an execution.[164] On February 7, 2019, he was part of the majority in a 5–4 decision rejecting a Muslim inmate's request to delay execution in order to have an imam present with him during the execution.[165] Also in February 2019, Roberts sided with Kavanaugh and the court's four liberal justices in a 6–3 decision to block the execution of a man with an "intellectual disability" in Texas.[166][167]

Affirmative action

Roberts opposes the use of race in assigning students to particular schools, including for purposes such as maintaining integrated schools.[168] He sees such plans as discrimination in violation of the Constitution's Equal Protection Clause and Brown v. Board of Education.[168][169] In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, the Court considered two voluntarily adopted school district plans that relied on race to determine which schools certain children may attend. The Court had held in Brown that "racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional,"[170] and later, that "racial classifications, imposed by whatever federal, state, or local governmental actor, ... are constitutional only if they are narrowly tailored measures that further compelling governmental interests,"[171] and that this "[n]arrow tailoring ... require[s] serious, good faith consideration of workable race-neutral alternatives."[172] Roberts cited these cases in writing for the Parents Involved majority, concluding that the school districts had "failed to show that they considered methods other than explicit racial classifications to achieve their stated goals."[173] In a section of the opinion joined by four other justices, Roberts added that "[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race."

On June 29, 2023, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, which held that race-based affirmative action in both public and private universities violates the Equal Protection Clause.[174]

Free speech

Roberts wrote the majority opinion in the 2007 student free speech case Morse v. Frederick, ruling that a student in a public school-sponsored activity does not have the right to advocate drug use on the basis that the right to free speech does not invariably prevent the exercise of school discipline.[175]

On April 20, 2010, in United States v. Stevens, the Court struck down an animal cruelty law. Writing for an 8–1 majority, Roberts found that a federal statute criminalizing the commercial production, sale, or possession of depictions of cruelty to animals was an unconstitutional abridgment of the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. The Court held that the statute was substantially overbroad; for example, it could allow prosecutions for selling photos of out-of-season hunting.[176]

On March 2, 2011, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Snyder v. Phelps, holding that speech as a matter of public concern, even if considered offense or outrageous, cannot be the basis of liability for a tort of emotional stress.[177][178] In doing so, he wrote that comments Phelps made constituted "matters of public import" as they related to societal issues and that Snyder was not determined to be a "captive audience" as determined by the captive audience doctrine.[179][180] In his conclusion, Roberts wrote, "On the facts before us, we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a nation, we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate."[181]

Health care reform

On June 28, 2012, Roberts wrote the majority opinion in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, which upheld a key component of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act by a 5–4 vote. The Court found that although the Act's "individual mandate" component could not be upheld under the Commerce Clause, the mandate could be construed as a tax and was therefore valid under Congress's authority to "lay and collect taxes."[182][183] At the same time, the Court overturned a portion of the law related to the expansion of Medicaid; Roberts wrote that "Congress is not free ... to penalize states that choose not to participate in that new program by taking away their existing Medicaid funding."[183] Sources within the Supreme Court said that Roberts switched his vote regarding the individual mandate sometime after an initial vote[184][185] and that he largely wrote both the majority and minority opinions.[186] This extremely unusual circumstance has also been used to explain why the minority opinion was unsigned, itself a rare phenomenon at the Supreme Court.[186]

LGBT rights

In Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013), Roberts wrote the 5–4 majority opinion holding that petitioners, appealing a lower court ruling that California's Proposition 8 was unconstitutional, lacked standing to sue, with the result that same-sex marriages resumed in California.[187] Roberts dissented in United States v. Windsor, in which a 5–4 majority ruled that key parts of the Defense of Marriage Act were unconstitutional.[188] The court found that the federal government must recognize same-sex marriages that certain states have approved. Roberts dissented in Obergefell v. Hodges, in which Kennedy wrote for the majority, again 5–4, that same-sex couples had a right to marry.[189] In Pavan v. Smith, the Supreme Court "summarily overruled" the Arkansas Supreme Court's decision that the state does not have to list same-sex spouses on birth certificates; Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch dissented, but Roberts joined the majority.[190] In the cases of Bostock v. Clayton County, Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2020), heard together, Roberts ruled with the 6–3 majority that businesses cannot discriminate against LGBT people in matters of employment.[191] In October 2020, Roberts joined the justices in an "apparently unanimous" decision to reject an appeal from Kim Davis, who refused to provide marriage licenses to same-sex couples.[192]

In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia (2021), Roberts joined a unanimous decision in favor of a Catholic adoption agency that the City of Philadelphia had denied a contract for its policy not to adopt to same-sex couples; he was also part of the majority that declined to reconsider or overturn Employment Division v. Smith, "an important precedent limiting First Amendment protections for religious practices."[193] Also in 2021, he was one of the six justices who declined to hear an appeal by a Washington State florist who refused service to a same-sex couple based on her religious beliefs against same-sex marriage; because four votes are required to hear a case, the lower court judgments against the florist remain in place.[194][195][196] In November 2021, Roberts voted with the majority in a 6–3 decision to reject an appeal from Mercy San Juan Medical Center, a hospital affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, which had sought to deny a hysterectomy to a transgender patient on religious grounds.[197] Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch dissented; the vote to reject the appeal left in place a lower court ruling in the patient's favor.[198][199]

Voting Rights Act

This section may relate to a different subject or has undue weight on an aspect of the subject. (August 2022) |

During his tenure as chief justice, Roberts has struck down voting rights protections provided by the Voting Rights Act.[200][201][202] In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), he struck down requirements that states and localities with a history of racially motivated voter suppression obtain federal preclearance before making any changes to voting laws. Research shows that preclearance led to increases in minority congressional representation and minority turnout.[203][204] Five years after the ruling, nearly 1,000 U.S. polling places had closed, many of them in predominantly African-American counties. There were also cuts to early voting, purges of voter rolls, and impositions of strict voter ID laws.[205][206] A 2020 study found that jurisdictions that had previously been covered by preclearance substantially increased their voter registration purges after Shelby.[207] Virtually all restrictions on voting after the ruling were enacted by Republicans.[208]

In 2023, Roberts and Kavanaugh joined the liberals in Allen v. Milligan, a 5–4 decision holding that Alabama's congressional redistricting plan violated Section 2 of the VRA. Writing for the majority, Roberts concluded that Alabama must draw an additional majority-minority district, and determined that Section 2 of the Act is constitutional in the redistricting context. Writing for himself and the three liberal justices, Roberts also wrote that "[t]he contention that mapmakers must be entirely 'blind' to race has no footing in our §2 case law."[209][210][211]

Awards and honors

In 2007, Roberts received an honorary degree from the College of the Holy Cross. He also delivered a commencement address at Holy Cross that year.[212][213][214] In 2023, Roberts was awarded the Henry J. Friendly Medal of the American Law Institute.[215]

Personal life

Roberts and his wife, Jane Sullivan, were married on July 27, 1996,[216] in the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle.[217] J. Michael Luttig was a groomsman at their wedding.[218] Sullivan is a lawyer who met Roberts in New York. After graduating from the College of the Holy Cross, she received a master's degree in mathematics from Brown University and a Juris Doctor degree from the Georgetown University Law Center.[219] She became a prominent legal recruiter at the firms of Major, Lindsey & Africa and Mlegal.[220] Like Clarence Thomas, Sullivan has been on Holy Cross's board of trustees. John and Jane Roberts live in Chevy Chase, Maryland.[221][14] They have two adopted children.[82]

During the late 1990s, while working for Hogan & Hartson, Roberts served as a member of the steering committee of the Washington, D.C., chapter of the conservative Federalist Society, although he has said he has little recollection of any involvement.[222]

Health

In 2007, Roberts had a seizure at his vacation home in St. George, Maine,[223][224] and stayed overnight at a hospital in Rockport, Maine;[225] doctors found no identifiable cause.[223][224][226][227] Roberts had suffered a similar seizure in 1993[223][224][226] but an official Supreme Court statement said that a neurological evaluation "revealed no cause for concern." Federal judges are not required by law to release information about their health.[223]

On June 21, 2020, Roberts fell at a Maryland country club; his forehead required sutures and he stayed overnight in the hospital for observation. Doctors ruled out a seizure and believed dehydration had made Roberts light-headed.[228]

Selected works

- Roberts, John (1978). "Developments in the Law: Zoning – III. The Takings Clause". Harvard Law Review. 91: 1462–1501. doi:10.2307/1340392. JSTOR 1340392. Section III ("The Takings Clause") of the unsigned student note "Developments in the Law: Zoning" (pp. 1427–1708).

- Roberts, John (1978). "The Supreme Court, 1977 Term – Contract Clause—Legislative Alteration of Private Pension Agreements: Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus". Harvard Law Review. 92: 86–98. doi:10.2307/1340566. JSTOR 1340566. Subsection C ("Contract Clause—Legislative Alteration of Private Pension Agreements: Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus") of Section I ("Constitutional Law") of the unsigned student note "The Supreme Court, 1977 Term" (pp. 1–339).

- Roberts, John; Prettyman, Elijah Barrett Jr. (February 26, 1990). "New Rules and Old Pose Stumbling Blocks in High Court Cases". Legal Times.

- Roberts, John; Starr, Kenneth; Mueller III., Robert Swan; Lazerwitz, Michael (1991). "At Issue: The Noriega Tapes. Yes: The Order was Constitutional". ABA Journal. 77 (2): 36. JSTOR 20761397.

- Roberts, John (1993). "Article III Limits on Statutory Standing". Duke Law Journal. 42 (6): 1219–1232. doi:10.2307/1372783. JSTOR 1372783.

- Roberts, John (March 28, 1993). "Riding the Coattails of the Solicitor General". Legal Times.

- Roberts, John (May 5, 1993). "Rule of Law: The New Solicitor General And the Power of the Amicus". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Roberts, John (1994). "The 1992–1993 Supreme Court". Public Interest Law Review. 1994: 107.

- Roberts, John (1995). "Forfeitures: Does Innocence Matter". New Jersey Law Journal. 142: 28.

- Roberts, John (1997). "Thoughts on Presenting an Effective Oral Argument" (PDF). School Law in Review. 1997: 7-1–7-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2005. Retrieved September 10, 2005.

- Roberts, John; Starr, Kenneth; Mahoney, Maureen (2003). "Rex E. Lee Conference on the Office of the Solicitor General of the United States: Bush Panel". Brigham Young University Law Review. 2003 (1): 62–82.

- Roberts, John (2005). "Oral Advocacy and the Re-emergence of a Supreme Court Bar". Journal of Supreme Court History. 30 (1): 68–81. doi:10.1111/j.1059-4329.2005.00098.x. S2CID 145369518.

- Roberts, John (2005). "A Tribute to Chief Justice Rehnquist" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 119: 1–2. JSTOR 4093552. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009.

- Roberts, John (2006). "Tribute to Judge Edward R. Becker". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 155 (1): 3–4. JSTOR 40041300.

- Roberts, John (2006). "What Makes the D.C. Circuit Different? A Historical View" (PDF). Virginia Law Review. 92 (3): 375–389. JSTOR 4144947. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- Roberts, John (2016). "In Memoriam: Justice Antonin Scalia" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 130 (1): 1–2. JSTOR 44072402.

- Roberts, John (2018). "In Tribute: Justice Anthony M. Kennedy" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 132 (1): 1–3.

- Roberts, John (2020). "Memoriam: Justice John Paul Stevens" (PDF). Harvard Law Review. 133 (3): 747–748.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Chief Justice)

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

- List of United States chief justices by time in office

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases decided by the Roberts Court

Notes

- ^ Roberts turned down an offer to pursue a doctorate in history at Harvard on a full scholarship.[28]

- ^ Roberts' colleagues on the Harvard Law Review also included Jane C. Ginsburg, the daughter of Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[29]

- ^ Harvard students considered a clerkship with Friendly to be "the gold standard"; Charles Davidow, a fellow member of the Harvard Law Review, described Roberts as "a superstar in law school, and the fact that Friendly picked him would be testament to that".[31]

- ^ Roberts has considered Friendly "the most influential figure in his life."[36] During his Supreme Court confirmation hearings in 2005, Roberts later testified about Friendly: "He had such a total commitment to excellence in his craft, at every stage of the process. Just a total devotion to the rule of law and the confidence that if you just worked hard enough at it, you'd come up with the right answers."[36]

- ^ Starr chose Roberts to assist O'Connor in matters concerning abortion during her hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Roberts later recalled that "the approach was to avoid giving specific responses to any direct questions on legal issues likely to come before the court, but demonstrating in the response a firm command of the subject area and awareness of the relevant precedents and arguments." O'Connor later received widespread support and was confirmed 99–0 on September 21, 1981.[39]

- ^ Democrats Ted Kennedy (Massachusetts), Chuck Schumer (New York), and Dick Durbin (Illinois) were those who opposed Roberts's nomination.[78]

- ^ Roberts, like some other judges on the D.C. Circuit, borrowed from classical works in writing his opinions, and he often quoted Voltaire, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Homer. According to legal scholar Laura Krugman Ray, he was intent on "finding ways to leaven his utilitarian prose with personalized elements of diction, metaphor, allusion, syntax, and tone."[83]

- ^ Including two important decisions, firstly in Sierra Club v. E.P.A. (2004), rejecting claims of an environmental rights group that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should have enforced stricter measures on air pollution, then in Independent Equipment Dealers Ass'n v. E.P.A. (2004), concerning the EPA's role under the Administrative Procedure Act.[82]

- ^ Usually ruling in favor of the government, including in United States v. Bolla (2003), which upheld a harsh securities fraud sentence, and in United States v. Lawson (2005), which affirmed a bank robbery conviction based on photo identification.[84]

References

- ^ "Roberts, John G.: Files, 1982-1986" (PDF). Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. February 12, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Appointment of Robert M. Kruger as Associate Counsel to the President". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Bassetti, Victoria (July 1, 2020). "John Roberts is an institutionalist, not a liberal". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (July 13, 2020). "John Roberts Is Just Who the Supreme Court Needed". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, Peter W. (May 20, 2021). "Analysis | Chief Justice John Roberts: From key swing vote to potential bystander?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ Cole, David (August 15, 2024). "The Supreme Court's Power Grab". The New York Review of Books. Vol. 71, no. 13. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ "Entering a new Supreme Court term, John Roberts is as enigmatic as ever". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 186–187.

- ^ a b "Biographies of the Robes: John Glover Roberts, Jr". PBS. WNET. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 466, 468.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 17.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 18, 21.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Purdum, Todd S.; Jodi Wilgoren; Pam Belluck (July 21, 2005). "Court Nominee's Life Is Rooted in Faith and Respect for Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Stone 2020, p. 1015–1016.

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey (May 18, 2009). "No More Mr. Nice Guy". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Stone 2020, p. 1015.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 29.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 35–36.

- ^ a b c Guren, Adam M. (July 15, 2005). "Alum Tapped for High Court". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c Biskupic 2019, p. 38.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 36.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 35.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 40, 44.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 39.

- ^ Edidin, Peter (July 31, 2005). "Judge Roberts, Meet Daniel Webster". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Biskupic 2019, p. 44–45.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1217.

- ^ Toobin 2007, p. 262.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, pp. 45–46; Snyder 2010, p. 1217.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1215, 1217.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 46; Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 467–468.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1218–1219.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 1221.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 51–52, 85–86.

- ^ a b Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 468.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 61, 63–64.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 65.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 66–67.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 70.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 69.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 73, 76, 81, 96, 124–125.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 81–82; Greenburg 2007, p. 38.

- ^ "Former Hogan & Hartson Partner John G. Roberts, Jr. Confirmed as Chief Justice of the United States" (Press release), Hogan Lovells, September 29, 2005.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 93.

- ^ "Biographies of the Justices – Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 470.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 94–95.

- ^ Register of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Courts (55th ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office Washington: 1990. 1990. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 95.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 96.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 471.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 102–104.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 470–471.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 97–99.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 99.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 1149, 1151, 1215–1216.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 109–110.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, pp. 111–112; Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 471.

- ^ "Judicial Nominations – Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr". George W. Bush | White House archives. whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 186.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 112.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 471–473.

- ^ Stone 2020, p. 1019.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 113.

- ^ Serrano, Richard A. (August 4, 2005). "Roberts Donated Help to Gay Rights Case". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ Stone 2020, p. 1019–1020.

- ^ Toobin 2007, p. 149.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 1–2, 119.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 119–120.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 186–187; Biskupic 2019, p. 131.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 117.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 118–119.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 119.

- ^ Nominations, 2001 Congressional Record, Vol. 147, Page S4773 Archived December 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (May 9, 2001)

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 131; Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 473.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 132.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Toobin 2007, p. 264; Biskupic 2019, p. 133, 135; Greenburg 2007, p. 187.

- ^ John Roberts at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ Toobin 2007, p. 264–265.

- ^ a b c Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 473.

- ^ a b c Biskupic 2019, p. 136.

- ^ a b Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 474.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 473–475.

- ^ Friedman & Israel 2013, p. 475.

- ^ Biskupic 2019, p. 138.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 185–186, 188.

- ^ "Chief Justice Nomination Announcement". C-SPAN. September 5, 2005. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary (2003). "Confirmation Hearings on Federal Appointments". Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, 108th Congress, 1st Session Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "Transcript: Day One of the Roberts Hearings". The Washington Post. September 13, 2005. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ "Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate" (PDF). Access.gpo.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Testimony of the Honorable Dick Thornburgh" (Press release). United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. September 15, 2005. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 232.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Amy; Charles Babington (September 15, 2005). "Roberts Avoids Specifics on Abortion Issue". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 226.

- ^ Greenburg 2007, p. 233.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (June 2006). "The Day After Roe". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 12, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Roll call vote on the Nomination (Confirmation Samuel A. Alito, Jr., of New Jersey, to be an Associate Justice)". United States Senate. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Roll call vote on the Nomination (Confirmation Sonia Sotomayor, of New York, to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court)". United States Senate. August 6, 2009. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Roll call vote on the Nomination (Confirmation Elena Kagan of Massachusetts, to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U.S.)". United States Senate. August 5, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "Roll call vote on the Nomination (Confirmation Neil M. Gorsuch of Colorado, to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U.S.)". United States Senate. April 7, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ "A conversation with Justice Antonin Scalia". Charlie Rose. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey (May 25, 2009). "No More Mr. Nice Guy". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Epps, Garrett (September 8, 2014). American Justice 2014: Nine Clashing Visions on the Supreme Court. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 21–33. ISBN 978-0-8122-9130-8. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ Diane S. Sykes, "Of a Judiciary Nature": Observations on Chief Justice Roberts's First Opinions, 34 Pepp. L. Rev. 1027 (2007).

- ^ Silagi, Alex (May 1, 2014). "Selective Minimalism: The Judicial Philosophy Of Chief Justice John Roberts". Law School Student Scholarship. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ "Chief Justice Says His Goal Is More Consensus on Court". The New York Times. The Associated Press. May 22, 2006. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (January 15, 2019). "Opinion | Trump Tries to Destroy, and Justice Roberts Tries to Save, What Makes America Great". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ "Chief justice rebukes Trump's Obama taunt". BBC News. November 21, 2018. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "In rare rebuke, Chief Justice Roberts slams Trump for comment about 'Obama judge'". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Cassidy, John. "Why Did Chief Justice John Roberts Decide to Speak Out Against Trump?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (January 21, 2020). "John Roberts presides over the impeachment trial -- but he isn't in charge". CNN. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Kruzel, John (January 27, 2021). "Why John Roberts's absence from Senate trial isn't a surprise". The Hill. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Scalia, Antonin; Garner, Bryan A. (2008). Making your case: the art of persuading judges. St. Paul, Minnesota: Thomson/West. ISBN 9780314184719.

- ^ a b Rosen, Jeffrey. "Jeffrey Rosen: Big Chief – The New Republic". The New Republic. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Coyle, Marcia (2013). The Roberts Court: the struggle for the constitution. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451627527.

- ^ Bowers, Jeremy; Liptak, Adam; Willis, Derek (June 23, 2014). "Which Supreme Court Justices Vote Together Most and Least Often". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Empirical SCOTUS: Is Kavanaugh as conservative as expected?". SCOTUSblog. April 3, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Kirchgaessner, Stephanie (October 11, 2021). "John Roberts is no longer the leader of his own court. Who, then, controls it?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022.

- ^ Huq, Aziz (September 15, 2021). "The Roberts Court is Dying. Here's What Comes Next". Politico. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 24, 2022). "June 24, 2022: The Day Chief Justice Roberts Lost His Court". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (June 26, 2022). "Chief Justice John Roberts lost the Supreme Court and the defining case of his generation". CNN. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022.

- ^ Higgins, Tucker (June 26, 2018). "Supreme Court rules that Trump's travel ban is constitutional". CNBC. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Note, The Supreme Court, 2017 Term — Leading Cases, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 327 (2018).

- ^ Josh Blackman, The Travel Bans, 2017-2018 Cato Sup. Ct. Rev. 29 (2018).

- ^ "Opinion analysis: Divided court upholds Trump travel ban". SCOTUSblog. June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court Rules Trump Cannot Block Release of Financial Records". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Pete (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court rules Trump will have to fight to keep secret his taxes, financial records". NBC News. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Sheth, Sonam; Samuelsohn, Darren (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court rules against Trump in 2 landmark cases about his taxes and financial records". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Robert (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court says Manhattan prosecutor may pursue Trump's financial records, denies Congress access for now". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Search - Supreme Court of the United States". supremecourt.gov. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ O'Brien, Timothy L. (July 9, 2020). "Politics & Policy: The Supreme Court Puts Trump in His Place". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hurley, Lawrence (July 1, 2024). "Supreme Court provides win to Trump, ruling he has immunity for many acts in election interference indictment". NBC News. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ Dallas, Kelsey (July 1, 2024). "Supreme Court punts Trump's presidential immunity case back to lower court". Deseret News.

- ^ Kruzel, John; Chung, Andrew (July 1, 2024). "US Supreme Court rules Trump has broad immunity from prosecution". Reuters.

- ^ Totenberg, Nina (July 1, 2024). "Supreme Court says Trump has absolute immunity for core acts only". NPR.

- ^ Howe, Amy (July 1, 2024). "Justices rule Trump has some immunity from prosecution". SCOTUSblog.

- ^ Millhiser, Ian (July 1, 2024). "The Supreme Court's disastrous Trump immunity decision, explained". Vox.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa; Legare, Robert (July 2, 2024). "Supreme Court rules Trump has immunity for official acts in landmark case on presidential power". CBS News.

- ^ Marimow, Ann; Barrett, Devlin (July 1, 2024). "Justices give presidents immunity for official acts, further delaying Trump's trial". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc". Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ "Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. v. FEC". FEC.gov. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Citizens United v. Federal Election Comm'n (Roberts, C. J., concurring), January 21, 2010

- ^ "McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission". Oyez. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ "Williams-Yulee v. The Florida Bar". Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Andrew Lessig, "Williams-Yulee v. The Florida Bar: Judicial Elections as the Exception", The DIGEST: National Italian American Bar Association Law Journal, Apr. 24, 2016.

- ^ Stracqualursi, Ariane de Vogue,Fredreka Schouten,Veronica (July 1, 2021). "Supreme Court invalidates California's donor disclosure requirement | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Renee E. Williams (2008). "Third Party Consent Searches After Georgia v. Randolph: Dueling Approaches to the Dueling Roommates" (PDF). Bu.edu. p. 950. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Utah v. Strieff" (PDF). supremecourt.gov. June 20, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ "CARPENTER v. UNITED STATES" (PDF). supremecourt.gov. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Justice Thomas wrote separately to emphasize this: "whether the Act constitutes a permissible exercise of Congress' power under the Commerce Clause is not before the Court". law.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Tucker (December 10, 2018). "Supreme Court hamstrings states' efforts to defund Planned Parenthood". cnbc.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane (December 10, 2018). "Supreme Court sides with Planned Parenthood in funding fight". cnn.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court blocks Louisiana abortion law". Reuters TV. Archived from the original on February 10, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "Supreme Court Hands Abortion-Rights Advocates A Victory In Louisiana Case". NPR.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Supreme Court strikes, in 5–4 ruling, down restrictive Louisiana abortion law". NBC News. June 29, 2020. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Liptak, Adam (February 7, 2019). "Supreme Court Blocks Louisiana Abortion Law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Totenberg, Nina; Montanaro, Domenico; Gonzales, Richard; Campbell, Barbara (February 7, 2019). "Supreme Court Stops Louisiana Abortion Law From Being Implemented". NPR.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "How Brett Kavanaugh tried to sidestep abortion and Trump financial docs cases". CNN. July 29, 2020. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Liptak, Adam; Goodman, J. David; Tavernise, Sabrina (September 1, 2021). "Supreme Court, Breaking Silence, Won't Block Texas Abortion Law". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane. "Why John Roberts blocked an execution". CNN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "Muslim man executed after U.S. Supreme Court denies request for imam's presence". Reuters. February 8, 2019. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Rowland, Geoffrey (February 19, 2019). "Supreme Court tosses death sentence for Texas man". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "Divided Supreme Court blocks Texas from executing intellectually disabled man, citing 'lay stereotypes'". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey (2008). The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. New York: Doubleday. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-385-51640-2.

- ^ Day to Day (June 28, 2007). "Justices Reject Race as Factor in School Placement". NPR. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ "Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka". Supreme.justia.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

349 U.S. 294, 298 (1955) (Brown II)

- ^ Adarand Constructors v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 Archived January 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 227 (1995).

- ^ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 Archived November 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 339 (2003).

- ^ Parents Involved, slip op. at 16 Archived May 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Supreme Court bans colleges from considering race in admissions". The Independent. June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ Economist.com (June 28, 2007). "The Supreme Court says no to race discrimination in schools". The Economist. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ Tribune Wire Services. "Supreme court crushes law against animal cruelty videos and photos" Archived July 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2010.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (March 2, 2011). "Justices Rule for Protestors at Military Funerals". The New York Times.

- ^ "Supreme Court Rules 8-1 in Favor of Westboro Funeral Protesters". PBS Newshour. March 2, 2011.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (March 3, 2011). "Why the Supreme Court Ruled for Westboro Nation". Time.

- ^ Moraleda, Lucy (December 5, 2022). "Snyder v. Phelps: How Free Is Speech?". Gallatin School of Individualized Study.

- ^ Denniston, Lyle (March 2, 2011). "Commentary: Privacy, in different settings". SCOTUSblog.

- ^ Haberkorn, Jennifer (June 28, 2012). "Health care ruling: Individual mandate upheld by Supreme Court". Politico. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Cushman, John (June 28, 2012). "Supreme Court Lets Health Law Largely Stand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "New SCOTUS parlor game: Did Roberts flip?". Politico. June 30, 2012. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- ^ Crawford, Jan (July 1, 2012). "Roberts switched views to uphold health care law". CBS News. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Campos, Paul (July 3, 2012). "Roberts wrote both Obamacare opinions". Salon. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Mears, Bill. "Supreme Court dismisses California's Proposition 8 appeal – CNNPolitics". CNN. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Dan; Holpuch, Amanda (June 27, 2013). "Doma defeated on historic day for gay rights in US". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2018.