Roger Rogerson

Roger Rogerson | |

|---|---|

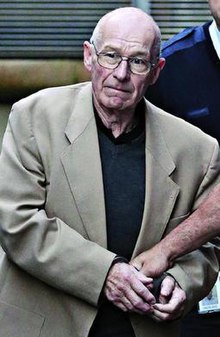

Rogerson leaving the Supreme Court in June 2016 | |

| Born | 3 January 1941 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 21 January 2024 (aged 83) Randwick, New South Wales, Australia |

| Other names | Roger the Dodger[1] |

| Occupation | Detective |

| Employer | New South Wales Police |

| Criminal status | Deceased during incarceration |

| Spouse(s) | Joy Archer Anne Melocco |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Peter Mitchell Award |

| Conviction(s) | Murder, drug trafficking, perverting the course of justice |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

Roger Caleb Rogerson (3 January 1941 – 21 January 2024) was an Australian detective sergeant in the New South Wales Police Force and a convicted murderer.[2][3] During his career, Rogerson received at least thirteen awards for bravery, outstanding policemanship and devotion to duty,[4][5] before being implicated in two killings, bribery, assault and drug dealing,[6] and then being dismissed from the force in 1986.

Rogerson was also known for his association with other New South Wales detectives who are reputed to have been corrupt, including Ray "Gunner" Kelly and Fred Krahe, and also with several organised crime figures, including Abe Saffron,[7] Christopher Dale Flannery, and Arthur "Neddy" Smith. Smith was a convicted heroin dealer, rapist and armed robber who claimed Rogerson gave him the "green light" to commit crimes in New South Wales, while Flannery specialised in contract killing.[8]

In 1999, Rogerson was convicted of perverting the course of justice and lying to the Police Integrity Commission, and in May 2014, Rogerson and fellow former NSW detective Glen McNamara were charged with the murder of 20-year-old student Jamie Gao, and taking his supply of drugs. Both pleaded not guilty in January 2015. Their trial was started in July 2015, but was aborted when McNamara's barrister Charles Waterstreet made a reference to Rogerson "killing two or three people when he was in the police force".[9][10] Following a retrial, both Rogerson and McNamara were found guilty of murder.[2] In September 2016, both were sentenced to life for the murder of Gao.

Early life

[edit]Rogerson was born in Sydney on 3 January 1941.[11] One of three children, he grew up in the suburb of Bankstown (moving there from Bondi at six years of age).[12]: 31–33 Rogerson's father Owen Rogerson immigrated from Kingston upon Hull, England during his career as a boilermaker; his mother Mabel Boxley immigrated from Cardiff, Wales, with her parents as a youth (her English-born father Caleb Boxley was the reason for Rogerson's middle name).[12]: 31–33 Rogerson attended Bankstown Central School and later Homebush Boys High School. In January 1958, he joined the New South Wales Police Cadet Service.[12]: 35 He had two daughters by his first wife, Joy Archer.[12]: 10

Police career

[edit]Rogerson worked on some of the biggest cases of the early 1970s, including the Toecutter Gang Murder and the Whiskey Au Go Go fire in Brisbane. Soon after the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub fire on 8 March 1973, Sydney detectives Roger Rogerson and Detective Sergeant Noel Morey were called to Brisbane to assist in the investigation. This was because John Andrew Stuart, accused of lighting the fire, had said criminals from Sydney were behind the nightclub extortion attempts.[13]

By 1978, Rogerson's reputation was sufficient to gain convictions based on the strength of unsigned records of interviews with prisoners (known as "police verbals"). He was brought in to investigate the Ananda Marga conspiracy case, despite having no connections to the Special Branch investigating the case. Tim Anderson, one of the three released in 1985, claimed the confession Rogerson extracted was fabricated, and that he and two other members of the Ananda Marga group were convicted in part because of Rogerson's fabrications.[14][15]

The Peter Mitchell Award was presented to Rogerson in 1980 for the arrest of escaped armed robber Gary Purdey. This was tainted by Purdey's claims that Rogerson assaulted him, prevented him from calling his solicitor and typed up to five different records of the interview.[14][dead link]

Shooting death of Warren Lanfranchi

[edit]Rogerson was responsible for the 1981 shooting death of Warren Lanfranchi.[16] During the inquest, the coroner found that Rogerson was acting in the line of duty, but a jury declined to find he had acted in self-defence. However, it was alleged by Lanfranchi's partner, Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, and later by Neddy Smith, that Rogerson had murdered Lanfranchi as retribution for robbing another heroin dealer who was under police protection and for firing a gun at a police officer. Huckstepp, a heroin addict and prostitute, appeared on numerous current affairs programs, including 60 Minutes and A Current Affair, demanding an investigation into the shooting. She also made statements to the New South Wales Police Internal Affairs Branch. Huckstepp was later murdered, her body found in a pond in Centennial Park.[16]

Charges of shooting Michael Drury

[edit]Fellow police officer Michael Drury has alleged that Rogerson was involved in his attempted murder. Drury claims he refused to accept a bribe Rogerson offered in exchange for evidence tampering in a heroin trafficking trial of convicted Melbourne drug dealer Alan Williams. On 6 June 1984, Drury was shot twice through his kitchen window as he fed his three-year-old daughter. Rogerson was charged with the shooting and Williams testified that Rogerson and Christopher Dale Flannery had agreed to murder Drury for A$50,000 each. However, on 20 November 1989, Rogerson was acquitted.[17][18]

Trial for drug dealing

[edit]Rogerson received a criminal conviction, which was overturned on appeal, for involvement in drug dealing, allegedly conspiring with Melbourne drug dealer Dennis Allen to supply heroin.[19]

After dismissal from the police force

[edit]Rogerson was dismissed from the New South Wales Police Force on 11 April 1986, while suspended from active service since 30 November 1984 as a result of the Drury investigation.[19] After leaving the force, Rogerson worked in the building and construction industry as a supplier of scaffolding. He also became an entertainer, telling stories of his police activities in a spoken-word stage show called The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, with former Australian footballers Warwick Capper and Mark "Jacko" Jackson.[20]

In 1988, Rogerson told a Bulletin reporter that he and the other lead detectives fabricated evidence. They did so because, although they 'knew' Stuart and Finch were involved, they had insufficient evidence to convict them. The police confirmed Rogerson was the 'mole' during an early 1990s secret investigation called 'Operation Graveyard'.[21] The journalist has refused to discuss the matter.[22]

Rogerson was subsequently convicted of perverting the course of justice in relation to A$110,000 deposited by him in bank accounts under a false name. He spent nine months in jail in 1990 before being released on bail pending an ultimately unsuccessful appeal. He spent a further three years in jail.[23]

On 17 February 2005, Rogerson and his wife, Anne Melocco, were convicted of lying to the 1999 Police Integrity Commission. Rogerson served twelve months of a maximum two-and-a-half-year sentence. He was released from Kirkconnell Correctional Centre on 17 February 2006. Melocco was sentenced to two years' periodic detention for the same offence.[24][failed verification] Following his release from prison in 2006, Rogerson resumed his entertainment career with Mark "Jacko" Jackson by appearing in a show called The Wild Colonial Psychos with Jackson and Mark "Chopper" Read.[19]

Writing and autobiography

[edit]In 2008, Rogerson reviewed episodes of the Underbelly series and Melbourne's underworld war in The Daily Telegraph.[25] He also wrote about the 2009 series of Underbelly for the same paper.[26]

In 2009, he published an autobiography about his time as a detective, entitled The Dark Side, launched by broadcaster Alan Jones.[27][28][12]

Extortion allegations

[edit]During legal proceedings surrounding the trial against suspects involved in the 2009 contract murder of Michael McGurk, the Supreme Court heard evidence that, while in the Cooma Correctional Centre in 2014, Rogerson, McNamara, and Fortunato "Lucky" Gattellari attempted to extort Ron Medich, a businessman and suspect for masterminding the murder of McGurk.[29][30][31]

Murder charge and conviction

[edit]On 27 May 2014, Rogerson was charged with the murder of Sydney student Jamie Gao, allegedly after a drug deal had gone wrong.[32] On 21 January 2015, he and his co-accused, Glen McNamara (also a former police detective), were committed to stand trial over the alleged murder.[33] On 6 March 2015, both accused were arraigned at a hearing in the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Both pleaded not guilty to the murder of Gao and also not guilty to supplying 2.78 kilograms (6.1 lb) of "ice" (methamphetamine). The men were due for trial in the Supreme Court on 20 July 2015.[34] On the second day, the trial was aborted because of the potential prejudice caused after McNamara's then-barrister Charles Waterstreet made a reference to Rogerson "killing two or three people when he was in the police force".[9][10]

A new trial started on 1 February 2016. On 15 June 2016, Rogerson and McNamara were found guilty of Gao's murder.[2] On 25 August 2016, Rogerson and McNamara faced a sentencing hearing. The NSW crown prosecutor, Christopher Maxwell sought for the judge to sentence Rogerson and McNamara for life, stating there was no distinction between a contract killing and killing for the purpose of financial gain.[35] One detective witness told The Daily Telegraph it was like tracking the "stars of Amateur Hour", regarding the killing of Jamie Gao.[36]

On 2 September 2016, Justice Geoffrey Bellew sentenced Rogerson and McNamara to life in prison, with the statement "The joint criminal enterprise to which each offender was a party was extensive in its planning, brutal in its execution and callous in its aftermath". Lawyers for both Rogerson and McNamara indicated they would appeal against the sentence.[37] However, neither Rogerson nor McNamara formally lodged appeals in time. In July 2019, Rogerson's last application for an extension of time to do so was refused by the NSW Supreme Court.[38] Nonetheless, Rogerson lodged an appeal in 2020,[39] which he lost.[40] The High Court refused to allow a further appeal.[41]

Death

[edit]On 18 January 2024, Rogerson was taken to Prince of Wales Hospital after suffering an aneurysm. He was taken off life support the following day,[42][43] and died on 21 January, at the age of 83.[44][45] Due to the New South Wales protocol surrounding deaths in custody, Rogerson's death is subject to both an official Corrective Services NSW and NSW police investigation, as well as a coronial inquest.[45] The inquest is scheduled for October 2024.[46]

Media portrayals

[edit]Richard Roxburgh portrayed Rogerson in the 1995 TV mini-series Blue Murder and its 2017 sequel Blue Murder: Killer Cop.[47]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Roger Rogerson: A life of crime and comedy". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Partridge, Emma (15 June 2016). "Roger Rogerson and Glen McNamara found guilty of the murder of Jamie Gao". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Disgraced former detective Roger Rogerson arrested at Sydney home, charged over alleged Jamie Gao murder". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Investigation into the relationship between Police and Criminals: First Report (PDF). Independent Commission Against Corruption. February 1994. ISBN 0-7310-2910-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2005. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ Rogerson, Roger (3 April 2008). "Q&A with Roger Rogerson". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ A bizarre twist has Rogerson answering questions of murder. The Northern Star, 31 May 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2016

- ^ Taylor, Grant. The Weekend West, 20–21 February 2016, p.9. "[A former WA detective said] he was introduced to Mr Rogerson [in June 1975] at the Raffles Hotel in Applecross just days after Shirley Finn [a Perth brothel keeper] was killed. Drinking with Mr Rogerson at the Raffles was [Perth vice-squad head] Bernie Johnson and Saffron"

- ^ Fontaine, Angus (23 January 2024). "Roger Rogerson: the 'icon of the force' who became the 'best policeman money could buy'". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Jury discharged in trial of Roger Rogerson, Glen McNamara for Jamie Gao murder The Sydney Morning Herald 28 July 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b Partridge, Emma; Hall, Louise (15 June 2016). "What the Rogerson jury didn't hear". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Rule, Andrew (26 May 2014). "Roger Rogerson: Telling it straight". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Rogerson, Roger Caleb (2009). The Dark Side. Melbourne: Kerr Publishing Pty Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9581283-1-5.

- ^ Plunkett 2018, p. 204.

- ^ a b see Take Two by Tim Anderson, 1992, "Take Two". Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.>

- ^ "Research Report on Trends in Police Corruption" (PDF). nsw.gov.au. Police Integrity Commission. Parliament of New South Wales, Australia. December 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ a b Morri, Mark (28 May 2014). "Disgraced Sydney detective Roger Rogerson is a consummate storyteller who loves a beer, writes Mark Morri". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Goodsir, D. Line of Fire: The inside story of the controversial shooting of undercover policeman Michael Drury, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 1995. ISBN 1-86448-002-5.

- ^ Hole, Jacquelyn (21 November 1989). "Jury Finds Roger Rogerson Not Guilty". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 47,495. p. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2015 – via Google News.

- ^ a b c Ansley, Greg (21 August 2004). "Comedy caper beyond a crime". The New Zealand Herald. APN New Zealand Limited. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Cashmere, Paul, (27 October 2003). "Who Are The Good The Bad and The Ugly?" at the Wayback Machine (archived 21 May 2007) Undercover Music News; Undercover Media Pty Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 October 2003.

- ^ Plunkett 2018, p. 253.

- ^ "Secret files detail 'fake report' on Whiskey Au Go Go blaze – The Australian (1 September 2018) – The Whiskey Au Go Go Massacre". September 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Jacobsen G., McClymont K. "Novel end as Rogerson gets two years to finish thriller". The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 February 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2016

- ^ I could have been chief: Roger Rogerson at the Wayback Machine (archived 29 May 2007). ninemsn.com.au; Nine National News. 13 March 2006. AAP. Archived from the original. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Rogerson, Roger (26 March 2008). Roger Rogerson reviews 'Underbelly' and blogs live Archived 30 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine blogs.news.com.au; Daily Telegraph blogs.

- ^ Rogerson, Roger (23 February 2009). Roger Rogerson reviews the third episode of Underbelly: A Tale of Two Cities Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine blogs.news.com.au; Daily Telegraph blogs. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ Goodsir, Darren. "Roger Rogerson myth can stand no longer", The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ FitzSimons, Peter (31 May 2014). "What's up Alan Jones? Isn't Roger Rogerson a mate?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ McClymont, Kate; Cormack, Lucy (26 April 2018). "As Medich is jailed, the man who organised the hit demands to be released". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Hoerr, Karl (7 February 2017). "'Former NSW cop Roger Rogerson recruited to extort money from property developer, jury told". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Begley, Patrick (7 February 2017). "Roger Rogerson part of $25 million plot to extort Ron Medich, court told". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Roger Rogerson charged over Jamie Gao murder; Gao shot twice in the chest, police allege". news.com.au. News Limited. 27 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Oriti, Thomas (22 January 2015). "Former detectives Roger Rogerson and Glen McNamara face murder trial over Jamie Gao death". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "Rogerson pleads not guilty to murder". 9news.com.au. AAP. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Margetts, Jayne (25 August 2016). "Jamie Gao murder: Rogerson and McNamara should be jailed for life, prosecutor says". ABC News.

- ^ McCallum, Nicholas (1 June 2014). "Gao was person of interest for years: AFP". 9News.

- ^ Hoerr, Karl (2 September 2016). "Jamie Gao murder: Roger Rogerson and Glen McNamara sentenced to life in prison". ABC News.

- ^ Day, Selina (18 July 2019). "Roger Rogerson likely to die in jail after court declines time extension to appeal". Seven News.

- ^ Scheikowski, Margaret (21 September 2020). "Roger Rogerson's murder appeal to start". Canberra Times. Australian Community Media. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Wells, Jamelle (16 July 2021). "Former detectives lose appeal over storage facility murder of drug dealer". ABC News. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Australian Associated Press (17 March 2023). "Roger Rogerson to die in jail after final appeal over murder conviction fails". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Jeffrey, Daniel (19 January 2024). "Australia's most disgraced cop Roger Rogerson hospitalised, close to death". Nine News. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Notorious cop Roger Rogerson on verge of death". News.com.au. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Disgraced former NSW detective Roger Rogerson dies aged 83". ABC News. 21 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b McClymont, Kate; McSweeney, Jessica (22 January 2024). "Corrupt former police officer Roger Rogerson dead at 83". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Bolza, Miklos (25 June 2024). "Coroner to examine killer cop Roger Rogerson's last days". www.9news.com.au. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ Byrnes, Holly (11 July 2017). "Roger Rogerson telemovie Blue Murder: Killer Cop fast-tracked to air by Channel Seven". News Corp Australia Network. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

References

[edit]- McNab, D. The Dodger – Inside the world of Roger Rogerson, Pan Macmillan, Sydney 2006, ISBN 9781405037518

- McNab, D. Killing Mr Rent-A-Kill, Pan Macmillan, Sydney 2012, ISBN 9781742611594

- Goodsir, D. Line of Fire: The inside story of the controversial shooting of undercover policeman Michael Drury, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 1995 ISBN 1-86448-002-5

- Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service Final Report – Volume 1 – Corruption

- Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service Final Report – Volume 2 – Reform

- Roger Rogerson at the Wayback Machine (archived 5 November 2006) Melbourne, Australia Crime website. Archived from the original

- Geesche Jacobsen, Kate McClymont (21 February 2005). The honest cop who pays for the sins of his brother The Sydney Morning Herald

- Roger Rogerson convicted on ASIC charges, Australian Securities & Investments Commission 22 October 2001.

- The life and times of Roger Rogerson The Age Documentary. Archived 19 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Plunkett, Geoff (2018). The Whiskey Au Go Go Massacre: Murder, Arson and the Crime of the Century. Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 9781925675443.

- 1941 births

- 2024 deaths

- 20th-century Australian criminals

- 21st-century Australian criminals

- Australian autobiographers

- Australian crime writers

- Australian drug traffickers

- Australian male criminals

- Australian gangsters

- Australian people convicted of murder

- Australian people of Welsh descent

- Australian people of English descent

- Australian police officers convicted of crimes

- Australian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Criminals from Sydney

- Police detectives

- Organised crime in Sydney

- People convicted of murder by New South Wales

- Police officers convicted of drug trafficking

- Police officers convicted of murder

- Police officers convicted of planting evidence

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by New South Wales

- Australian people who died in prison custody

- Prisoners who died in New South Wales detention

- Deaths from intracranial aneurysm