Jack Longland

Sir John Laurence Longland (26 June 1905 – 29 November 1993) was a British educator, mountain climber, and broadcaster.

After a brilliant student career Longland became a don at Durham University in the 1930s. He formed a lifelong concern for the welfare of unemployed people, and after a time working in community service he moved to become an educational administrator, retiring in 1970. Among his achievements was the establishment of White Hall in Derbyshire, the country's first local authority Outdoor Pursuits Centre for young people.

As a young man Longland was prominent among British rock-climbers, taking a distinguished part in the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition. Later in life he was active in the affairs of the British Mountaineering Council.

Longland was a familiar broadcaster on BBC Radio, appearing regularly from the late 1940s until the 1970s in the long-running Round Britain Quiz, Any Questions?, and the panel game My Word!, which he chaired for twenty years from 1957.

Life and career

[edit]Longland was the eldest son of the Rev E. H. Longland (successively curate of Hagley, vicar of St Paul's, Warwick (1908–16) rector of St Nicholas's Droitwich (1916–27), and vicar of Cropthorne (1927)) and his wife, Emily, elder daughter of Sir James Crockett. Longland was educated at the King's School, Worcester, and Jesus College, Cambridge, where he was Rustat Exhibitioner and scholar, won a Blue for pole-vaulting, and gained a first in Part I of the Historical Tripos in 1926,[1] and first class honours with distinction in the English Tripos in 1927.[2]

After graduating, Longland was elected Charles Kingsley bye-fellow of Magdalene College for two years, and then spent a year in Germany as Austausch-student at Königsberg University, where he witnessed the early rise of Adolf Hitler.

While still in his twenties Longland established a reputation as a mountaineer. He liked to say that he started out "with a clothes line and a pair of old army boots", but in the words of an obituarist, "as a rock-climber he was brilliant. He will always be remembered for 'Longland's Climb', on Clogwyn Du'r Arddu, in Snowdonia, the first route right up that formidable crag. It gave him enormous pleasure to climb that route again with his son over 40 years later."[3] He was a member of two major British expeditions – in 1933 to Everest and in 1935 to East Greenland.[2] In the words of The Times, "His place in Everest legend remains secure, if only for his 1933 feat in bringing down eight sherpas from Camp Six to Base Camp after a blizzard had produced whiteout conditions obliterating all traces of their upward route."[2] He was invited to go on the 1938 Everest expedition, but declined, being by then heavily involved with public service work in England.[3]

Longland's first full-time academic post was as lecturer in English at Durham University from 1930 to 1936. In 1934 he married Margaret Lowrey Harrison in a ceremony conducted by the Bishop of Durham (Hensley Henson) assisted by Longland senior and two other clergymen.[4] There were two sons and two daughters of the marriage.[5]

During his time at Durham, Longland became increasingly concerned at the social problems caused by the Great Depression and unemployment in the Durham coalfields, and became an active member of the Labour Party.[2] He said later:

I came into educational administration at the end of the squalid and hungry thirties after some years working with unemployed Durham miners and their families. I think that those underfed children, their fathers on the scrapheap, and the mean rows of houses under the tip, all the casual product of a selfishly irresponsible society, have coloured my thinking ever since.[6]

He left the university to become deputy director of Durham's Community Service Council, taking over as director a year later. From 1940 until his retirement in 1970 he worked in the management of education, as deputy education officer for Hertfordshire (1940–42), director of education for Dorset (1942–49) and for Derbyshire (1949–70). In tandem with his main official duties he was Regional Officer of the National Council of Social Service, 1939–40, president of the Association of Education Officers, 1960–61, and chairman of the Mountain Leadership Training Board & Plas y Brenin, 1964–80.[5] He was also a member of eighteen national commissions, committees and advisory bodies.[n 1]. In his Derbyshire post in 1950 he set up the first local authority Outdoor Pursuits Centre (White Hall).[3] As a member of the Countryside Commission from 1969 to 1974 he played an important part in bringing increased protection for the countryside responsible, writing the commission's report that persuaded the government to strengthen the powers of National Park committees.[7]

In addition to his public service work, Longland was a frequent and popular broadcaster on BBC Radio.[6] In the late 1940s and 1950s he was the chairman of the series Country Questions in which a team of experts answered listeners' questions about the countryside; he was a panellist and later a question-master on the long-running Round Britain Quiz, and was a frequent member of the Any Questions? panel. He was in the chair for series for younger listeners, including The Younger Generation Question Time and Summer Parade. From August 1957 he succeeded John Arlott as chairman of the panel game My Word!, and remained in the role until he retired in December 1977.[8] He was described in The Times as "the perfect chairman, courteous, receptive, self-effacing and clearly well liked by the team".[9]

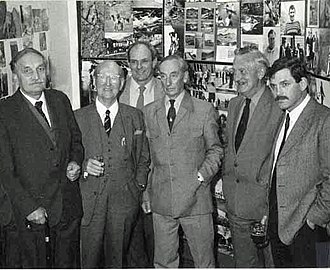

In 1990 Longland gave an address at a gathering to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Sir George Everest, the Surveyor General of India, after whom the mountain was named. The Royal Geographical Society hosted a gathering of climbers who had made or attempted the ascent of Everest. Among them were Lord Hunt, leader of the first successful British expedition in 1953, and Sir Edmund Hillary, who first climbed the mountain with Tenzing Norgay. Chris Bonington, Doug Scott, Stephen Venables and Harry Taylor talked of the post-war achievements, and Longland spoke about the early attempts on the mountain.[10]

Longland was knighted on his retirement in 1970 and was elected as President of the Alpine Club (UK) (1974-1976).[2] In his last years he was distressed, in the words of The Times, "to sit by and watch his educational work being undone by successively tougher Conservative secretaries of state." He died at the age of 88. His wife and one of his sons predeceased him.[6]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ These were the Colonial Office Social Welfare Advisory Committee, 1942–48; the Development Commission, 1948–78; Advisory Committee on Education in the Royal Air Force, 1950–57; Advisory Committee on Education in Germany, 1950–57; Central Advisory Council for Education in England and Wales, 1948–51; National Advisory Council on the Training and Supply of Teachers, 1951; Children's Advisory Committee of the Independent Television Authority, 1956–60; Wolfenden Committee on Sport, 1958–60; the Outward Bound Trust Council, 1962–73; Central Council of Physical Recreation Council and Executive, 1961–72; Electricity Supply Industry Training Board, 1965–66; Royal Commission on Local Government (Redcliffe-Maud Commission), 1966–69; the Sports Council, 1966–74 (Vice-Chairman 1971–74); the Countryside Commission, 1969–74; British Mountaineering Council, 1962–65 (Honorary Member, 1983); the Council for Environmental Education, 1968–75; the Commission on Mining and the Environment, 1971–72; and the Water Space Amenity Commission, 1973–76.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ "University News", The Times, 26 June 1926, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e "Obituary: Sir Jack Longland", The Times, 2 December 1993, p. 23

- ^ a b c Westmacott, Michael. "Obituary: Sir Jack Longland", The Independent, 4 December 1993

- ^ "Marriages", The Times, 3 June 1934, p. 1

- ^ a b c "Longland, Sir John Laurence (Sir Jack)", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2015 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Perrin, Jim. "Steady as a rock: Obituary", The Guardian, 1 December 1993, p. A37

- ^ Dower, Michael. "Obituary: Sir Jack Longland", The Independent, 11 December 1993

- ^ "Jack Longland", BBC Genome. Retrieved 22 November 2015

- ^ Davalle, Peter. "Personal Choice", The Times, 3 November 1978

- ^ Faux Ronald. "Everest heroes hold summit", The Times, 8 November 1990, p. 3