Jonathan M. Wilson

Jonathan M. Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Other names | J. M. Wilson, Wilson & Duke, Wilson & Hindes |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

| Years active | fl. 1839–1861 |

Jonathan Means Wilson (c. 1796 – possibly December 11, 1871), usually advertising as J. M. Wilson, was a 19th-century slave trader of the United States who trafficked people from the Upper South to the Lower South as part of the interstate slave trade. Originally a trading agent and associate to Baltimore traders, he later operated a slave depot in New Orleans. At the time of the 1860 U.S. census of New Orleans, Wilson had the second-highest net worth of the 34 residents who listed their occupation as "slave trader".

Biography

[edit]According to census records, Wilson was born in 1796 or 1797 in Virginia.[1][2] Wilson began his career in Baltimore as what was called a trading agent, originally associated with Hope H. Slatter.[3] In 1839 a J. W. Wilson of Baltimore was listed as the owner/shipper of 20 enslaved people being sent to S. F. Slatter in New Orleans on the barque Irad Terry.[4] Wilson and Slatter parted ways in June 1841.[5] Wilson was later associated with Joseph S. Donovan of Baltimore.[3] In August 1845 Jonathan Means Wilson, William H. Williams, and Henry F. Slatter, all placed identical ads in the New Orleans Bee stating that Mr. Edward Barnett was their "duly authorized agent" while they were gone from the city.[6] Historian Alexandra J. Finley describes Barnett as a "go-to notary for slave traders" who worked at one time as an agent for Wilson.[7]

In 1849 J. M. Wilson (as he usually styled himself in print) became head of his own business, located on Camden Avenue near Light Street in Baltimore.[3] His partner at this location was G. H. Duke from 1849 to 1856, and after 1856 he took on his son-in-law, Moses Hindes, as a business partner.[3] According to Frederic Bancroft, from his beginnings as an traveling agent Wilson rose through the ranks of the Upper South's enslavement-business community and eventually became a slave trader "of the first class" and among the "best known resident traders" of 1850s Baltimore, along with John N. Denning, Bernard M. Campbell & Walter L. Campbell, and Joseph S. Donovan.[8]

Wilson began operating a slave market in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, sometime in or before 1850.[7] The trade in the neighborhood just outside the French Quarter was vast; as historian Maurie D. McInnis put it in 2013: "In these blocks many of those listed as slave dealers were known to have very large slave jails where hundreds of enslaved people were held awaiting sale. The scale was so much larger than in Richmond. On a single day in 1854, a single newspaper column advertised nearly 700 slaves for sale: J. M. Wilson had 100 Virginia slaves; Thomas Foster had 250 slaves from Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky and Missouri; Charles LaMarque had 100 slaves; Wm. F. Talbott had 200 slaves; and James White had a 'likely lot.'"[11]

In 1852 a slave buyer used Louisiana's redhibition laws to demand a refund for an enslaved woman who had been "warranted sound" but died of incurable consumption shortly after he bought her from J. M. Wilson.[12]

A family reunification ad placed after the war described a family that had been broken into pieces in 1856 by Wilson's traffic in souls between Baltimore and New Orleans:[13]

MR. EDITOR--I desire to inquire for my mother, Susan Stewart. She belonged to Robert Berry, lived in Maryland and moved to Georgetown, D. C. Father's name was Richard. I was brought from Baltimore to New Orleans by a trader named Wilson, and sold in 1856. I left mother in the trader's yard. Sister Mary Elizabeth and brother Charley, who was a baby, I left there. My mother had five children when I left. Address me at Yazoo City, Miss., care of Barksdale & Smith. JACOB STEWART[13]

Wilson's 1856 emancipation of a woman named Caroline Williams (age 27), Alice Williams (age five), and Valentine Williams (age 18 months) suggests to historian Finley that "he was likely emancipating his enslaved concubine and two children with her".[7] The Natchez Trace collection at the University of Texas includes "a pre-printed slave bill of sale for 13 young women, aged 14–20, all having last names, including Queen Barksdale (age 15), sold as a group for $16,000 to planter Benjamin Roach by slave-trader J. M. Wilson. New Orleans, 1857".[14] Meanwhile, in Baltimore, Wilson & Hindes offered a $200 reward for the recapture of 20-year-old Oscar Henderson, described as a "bright mulatto, gray eyes and slightly pock marked, about 5 feet 8 or 9 inches high, rather thin visage and slender form".[15] There were multiple instances in the 1850s of lawyers getting writs of habeas corpus for people being held in the Wilson & Hindes slave jail in Baltimore, people whom the lawyers claimed were legally free: one such case was a boy named James Johnson in 1857 who may or may not have been sold by his own father, who still held title to his mother.[16]

In 1860 J. M. Wilson had the second-highest net worth of the 34 resident slave traders indexed as such in the 1860 New Orleans census. He came in behind T. B. Poindexter (likely a brother or cousin of John J. Poindexter) and just ahead of Bernard Kendig.[17] According to Alexandra J. Finley's group biography of four women affiliated with American slave traders, Mary Nelson, the woman identified as Wilson's housekeeper in the 1860 census was most likely his "concubine" and the six Nelson children living in the household were likely Wilson's progeny.[7][a]

In October 1860 William H. Nabb was working as a trading agent for Wilson & Hindes, based out of the Union Hotel in Easton, Maryland.[21] In December 1860 Wilson placed a newspaper advertisement in the New Orleans Times-Picayune offering "One Hundred and Fifty NEGROES from Virginia and Maryland Negroes...I will also receive during the season (every month) large supplies, exclusively from those states."[22] The "season" referenced is the slave-trading season, which typically ran from November to April, after one year's cotton or sugar harvest had been brought it and before the next year's needed to be planted out.[23] The last of Wilson & Hindes' "CASH FOR NEGROES" ads appeared in the Baltimore Sun in April 1861.[24]

Jonathan M. Wilson may have died in New Orleans on December 11, 1871, at the age of 75.[25]

Moses G. Hindes

[edit]Moses G. Hindes | |

|---|---|

Runaway slave ad, likely placed by Hindes (Baltimore Sun, January 6, 1863) | |

| Other names | M. G. Hindes, Wilson & Hindes |

| Occupation(s) | Brickmaker, bricklayer, slave trader |

Moses G. Hindes was a bricklayer, brickmaker, and slave trader of Baltimore in the United States. Hindes who was one of the principals in the American slave-trading firm Wilson & Hindes from 1856 until 1861 when interstate slave trading between Baltimore and New Orleans essentially ceased due to the American Civil War. Hindes was partners in the brick business with one John J. Hindes until 1843.[26] Hindes was based on Sharp Street according to Baltimore city directories of 1849, 1854 and 1856.[27][28][29] In 1854, businessman and slave trader Joseph S. Donovan hired Moses Hindes as the bricklayer for his construction of four large warehouses at the corner of Camden and Charles.[30] In November 14, 1854, Hindes married Rachel Ann Wilson, daughter of Jonathan M. Wilson.[31][32]

In 1859, a man named John Blittner was indicted for "receiving goods, knowing the same to have been stolen. The indictment charges that on the 1st of May, 1859, he received 15 yards of calico, 7 pairs children's shoes, 1 pairs wool socks and 1 cloth coat, the property of Moses G. Hindes and others, which had been stolen by a negro named Edward Ward, who has been indicted for the larceny."[33] Slave traders often provided new outfits of clothes for their prisoners,[8] in order to increase their appeal to potential buyers (the Duke Street slave jail complex in Alexandria even had its own tailor shop),[34] and it is possible that the stolen clothes and shoes may have been stockpiled in Wilson & Hindes' jail for this purpose.

Rachel Ann Wilson Hindes died in Baltimore in 1864 at age 34 after a "short and painful illness".[35] Hindes was listed as a brickmaker working on Sharp in the 1871 Baltimore city directory.[36] There was a Moses G. Hindes, bricklayer, located on Lombard street, in the 1890 city directory of Baltimore.[37] Moses Hindes and Rachel A. W. Hindes are both buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Baltimore.[38]

Additional images

[edit]-

"CASH FOR NEGROES" Slatter ad mentioning Wilson, reprinted The Liberator, February 24, 1843

-

It was illegal to trade slaves in Washington, D.C. after 1850, but it was not illegal to advertise the slave trade in Washington, D.C. newspapers

-

"Valuable servants at private sale" The Baltimore Sun, April 18, 1857

-

"Proceedings of the Courts" The Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1860

-

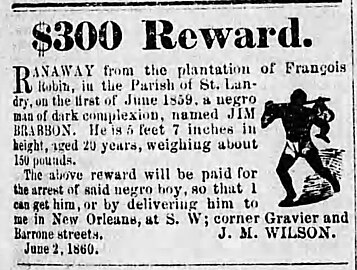

"$300 Reward - Jim Brabson" The Opelousas Patriot, August 3, 1861

See also

[edit]- List of American slave traders

- List of white American slave traders who had mixed-race children with enslaved black women

- Slave markets and slave jails in the United States

- History of slavery in Maryland

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- George Kephart – American slave trader (1811–1888)

- Contraband (American Civil War)

- Habeas corpus in the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mary Nelson was good friends with Lucy Ann Cheatham, the formerly enslaved "concubine" and/or housekeeper of slave trader John Hagan; Nelson delivered one of Cheatham's babies, and it was at Nelson's house that Cheatham eventually died in 1887.[7] Mary Nelson had possibly been trafficked to New Orleans on the brig Kirkwood in 1846 by shipper Joseph S. Donovan, at which time she was 16 years old, racially classified as "yellow", and 5 feet 1+1⁄2 inches tall.[18] Mary Nelson's daughter Mary Celeste Wilson listed J. M. Wilson as her father on her marriage record.[19] Mary Nelson's son Charles B. Wilson listed Jonathan Wilson as his father on his marriage record.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "Entry for Jonathan M Wilson and Ann Wilson, 1850", United States Census, 1850 – via FamilySearch

- ^ "Entry for J M Wilson and C M Price, 1860", United States Census, 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ^ a b c d Messick, Richard F. "Site of Jonathan Means Wilson Business - Site where the business of slavery once took place". Explore Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Inward Slave Manifests (Roll 12, 1837-1839)". afrigeneas.org. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Slavery and the Constitution. By William I. Bowditch". HathiTrust. p. 80. hdl:2027/yale.39002053504081. Retrieved 2024-01-13.

- ^ "untitled (column 1)". The New Orleans Bee. Vol. VIII, no. 125. August 1, 1845. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-11-06 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ a b c d e Finley, Alexandra J. (2020). An Intimate Economy: Enslaved Women, Work, and America's Domestic Slave Trade. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9781469655123. JSTOR 10.5149/9781469655130_finley. LCCN 2019052078. OCLC 1194871275.

- ^ a b Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 120–122 (Wilson), 320 (clothes). ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- ^ Johnson, Walter (2009). Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 48 (interstate firms), caption of illustration 8 (Slatter–Wilson–Bruin). ISBN 9780674039155. OCLC 923120203.

- ^ McInnis, Maurie D. (2013). "Mapping the Slave Trade in Richmond and New Orleans". Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. 20 (2): 102–125. doi:10.5749/buildland.20.2.0102. ISSN 1934-6832. S2CID 160472953.

- ^ McInnis, Maurie D. (Fall 2013). "Mapping the slave trade in Richmond and New Orleans". Building & Landscapes. 20 (2): 102–125. doi:10.5749/buildland.20.2.0102. JSTOR 10.5749/buildland.20.2.0102. S2CID 160472953. Project MUSE 538683.

- ^ "Race and Slavery Petitions - Petition 16391". Digital Library on American Slavery (dlas.uncg.edu). Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ a b "Jacob Stewart searching for his mother Susan Stewart · Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery". informationwanted.org. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ "Natchez Trace Collection Supplement, 1775-1965". txarchives.org.

- ^ "$200 Reward". The Baltimore Sun. 1857-09-16. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "A habeas corpus of James Johnson, alleged free negro". The Baltimore Sun. 1857-08-31. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Tansey, Richard (1982). "Bernard Kendig and the New Orleans Slave Trade". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 23 (2): 159–178. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4232168.

- ^ "Entry for Mary Nelson, 1846". Louisiana, New Orleans, Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels, 1807-1860 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ "Entry for John A Cammach and C W Cammach, 09 Mar 1873". Louisiana Parish Marriages, 1837-1957 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ "Entry for Chas B Wilson and Jonathan Wilson, 19 Feb 1878". Louisiana Parish Marriages, 1837-1957 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ "Scan of the Easton Gazette" (PDF). Maryland.gov.

- ^ "Arrival of negroes for sale". The Times-Picayune. 1860-12-14. p. 6. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ Johnson, Walter (2009). Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 49 (seasonality). ISBN 9780674039155. OCLC 923120203.

- ^ "The Baltimore Sun 30 Apr 1861, page 4". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Name: Jonathas M. Wilson, Age: 75, Birth Year: abt 1796, Death Date: 11 Dec 1871, Death Place: Orleans, Louisiana, USA, Volume Number: 53, Page number: 156 Source Citation - Louisiana State Archives; Baton Rouge, LA; Orleans Death Indices 1804-1876 - Original data: State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History. Vital Records Indices. Baton Rouge, LA, USA. "New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S., Death Records Index, 1804-1949". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Partnership dissolved". The Baltimore Sun. 1843-03-04. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Matchett's Baltimore directory. College Park University of Maryland. R.J. Matchett. 1849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0564, Page 0145 - Matchett's Baltimore Director For 1853-54". msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0544, Page 0158 - Woods' Baltimore Directory for 1856-57". msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "New Warehouses". The Baltimore Sun. 1854-02-27. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Index to Marriages in the (Baltimore) Sun, 1851-1860. Genealogical Publishing Com. 1978. ISBN 978-0-8063-0827-2.

- ^ "Married". The Baltimore Sun. 1854-11-21. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Receiving stolen goods". The Daily Exchange. 1859-09-21. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Once a Horrific Slave Pen, Now a Museum on Enslavement and Freedom". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "R.A. Hindes". The Baltimore Sun. 1864-06-11. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ The State Gazette and Merchants and Farmers' Directory for Maryland and District of Columbia ... Sadler, Drysdale & Purnell. 1871.

- ^ R.L. Polk & Co. Polk's Baltimore (Maryland) City business directory (1890-1891). College Park University of Maryland. Baltimore, R.L. Polk.

- ^ "Mount Olivet Cemetery, Baltimore, Maryland Names of Burials" (PDF).