Ightham

| Ightham | |

|---|---|

| |

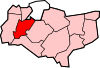

Location within Kent | |

| Population | 2,084 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ595565 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SEVENOAKS |

| Postcode district | TN15 |

| Dialling code | 01732 |

| Police | Kent |

| Fire | Kent |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

Ightham (/ˈaɪtəm/ EYE-təm) is a parish and village in Kent, England, located approximately four miles east of Sevenoaks and six miles north of Tonbridge. The parish includes the hamlet of Ivy Hatch.

Ightham is famous for the nearby medieval manor of Ightham Mote (National Trust), although the village itself is of greater antiquity. Ightham is not mentioned in the Domesday Book, but place-name evidence implies the name is derived from the Saxon 'Ehtaham'. 'Ehta' is a Jutish personal name, while 'ham' means settlement.

History

[edit]Stone Age

[edit]The presence of flint workshops at Oldbury Hill, excavated by Benjamin Harrison in 1905 and at Rose Wood on Ightham Common are evidence of the presence of humans in the Palaeolithic period.[2] The earliest trackway crossing the parish runs mainly as a ridgeway on top of the North Downs from East Kent to Salisbury Plain.

Iron Age

[edit]The fortification of Oldbury is dated to the late Iron Age. Oldbury was in the centre of a series of forts running 70 miles from Holmbury in Surrey to the west to Bigberry near Canterbury to the east. Oldbury is the largest of all at 123 acres.

Roman period

[edit]Benjamin Harrison of Ightham excavated the site of a tile works and possible Roman villa at Patchgrove Wood on the northwest edge of Oldbury Hill, close outside the parish.[2]

Medieval period

[edit]It is not known how the boundaries of the parish were established. There is no hard evidence for the establishment of a Saxon church, and Ightham was not mentioned in the Domesday Book. The inclusion of the church in the Textus Roffensis 1122-3 may reflect an older church as it may be a copy of an earlier Saxon list.[2] The network of parishes has been relatively stable since Anglo-Saxon times. In North West Kent parishes are single townships and cover 1000-6000 acres. Originally Ightham had 2611 acres. Tithes were paid to a parish priest.

In 1336 Edward II granted a request for permission to hold an annual fair in the village.

War Years

[edit]During the First World War 50 men of the parish died in the fighting. A war memorial was erected in their honour opposite the George and Dragon and unveiled on 5 December 1920 by Major General Sir William Furse. The Bishop of Rochester unveiled a tablet in their honour in February 1921 in St Peter's Church.[2]

With Ightham close to West Malling and Biggie Hill airfields, local people had a good view of the Battle of Britain in 1940, retreating to shelters if the fighting came too close. During the Blitz in 1940-41 Ightham was directly under a route then by German bombers and rocket on their way to attack London. Ightham was hit by 450 high-explosive bombs and 20 flying bombs or rocket. Olgdbury Hatch was badly burnt by incendiary bombs and in September 1940 a bomb hit two houses in Jubilee Crescent and another in Copt Hall.

Although bombs were dropped in the village, the school continued its usual pattern,. some of the children were evacuated to the West Country in 1941 but they soon returned. I June 1944 attacks by doodlebugs prompted the evacuation of Ightham children, as well as London evacuees in Ightham and a number of mothers to Devon and to Chard in Somerset. Petrol rationing was introduced early in the war and from January 1940, bacon, butter and sugar. By August 1942 all foods were regulated apart from bread, fish and vegetables. Each person had a ration book with exchangeable coupons. Everyone was encouraged to grow vegetables especially potatoes in their gardens and certain areas were set aside for allotments. Wartime meals included whale meat and rabbit.

Other

[edit]Ightham was famous for growing Kentish cob nuts. These seem to have been cultivated first by James Usherwood, who lived at Cob Tree Cottage. There was a public house nearby called the Cob Tree Inn, which has now reverted to a private house. There are still a number of cob trees in and around the village, but the work of pruning them and picking the nuts is labour-intensive, and the industry has fallen into decline.the local school has a cobnut as its logo.

Ightham also has its own football team, Ightham FC. Home games are played at the recreation ground adjoining the A25 motorway. It also has a Scout group 1st Ightam scouts

Main Manor Houses

[edit]

There were three Manor buildings House's in the original parish - the St Clere estate, Ightham Court (Court/Ightham Lodge) and Ightham Mote in the far south of the parish, at the northernmost Kent Weald. All three have origins stretching back to at least the late 12th Century. At the end of the 1400s the parish consisted of the village centre, several hamlets and a large number of dispersed farms.

St Peter’s Church

[edit]The earliest record of a church in Ightham is in the Textus Roffensis, a document commissioned by Earnulf, Bishop of Rochester in 1122/23, which lists the churches paying for blessed chrism oil on Thursday of Holy Week. Ightham was charged nine pence.[2]

The position of St Peter's Church on a knoll overlooking the village and with views over the parish is typically Saxon; however there is no trace of the earliest, perhaps wooden church. The fabric of the church is early Norman onwards. There are several fine monuments.[2]

Place Names

[edit]The name Ightham derived from the name of Ehte, possibly a Jute and ham or homestead. Many place names in the parish are of Anglo-Saxon or Jutish origin. Places were named as these settlers found them. Oldbury had clearly been fortified so the Jutes called it Eald-byrig from the Anglo-Saxon eald (old) and byrig (fortified place).[2]

Geography

[edit]The chalk North Downs have a layer of clay-with-flints in many places, including the finger of Ightham parish which reaches the crest of the Downs near Drane Farm. The highest point of the ancient parish in the north was near Drane Farm at over 700 feet above sea level.[2] The Vale of Holmesdale runs through the parish south of the Downs. There is a steep drop to about 320 feet in the Vale of Holmesdale south of St Clere. Along the length of the Vale runs a band of Gault, blue-grey clay, a mile wide with some alluvial deposits. This was cultivated by the early settlers.[2] To the south the land climbs gradually towards the northern part of Oldbury Hill. This hill covers 123 acres and climbs from 400 to over 600 feet then drops and climbs to nearly 650n feet at the edge of the Chart at Beacon or Raspit Hill.In the southern part of the parish are the Chart Hills or Greensand Ridge.Ightham common is at the western end of the eastern end of the eastern part of the hills and was covered with woodland and ferns, often boggy, limiting agricultural use. To the South of the Chart Hills the parish edges into the Wealden forest. The land was more suitable for agriculture than on the chart Hills. The inhabitants of Ightham would have used the forest to fatten their pigs in autumn on acorns.[2]

Demographics

[edit]| 2001 UK Census | Ightham ward | Tonbridge and Malling borough |

England |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 1,942 | 107,561 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 8.1% | 4.6% | 9.2% |

| White | 99.1% | 98.3% | 90.9% |

| Asian | 0.6% | 0.7% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.3% | 0.1% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 82.4% | 76.1% | 71.7% |

| Muslim | 0.2% | 0.3% | 3.1% |

| Hindu | 0% | 0.2% | 1.1% |

| No religion | 11.6% | 15% | 14.6% |

| Unemployed | 1.9% | 1.9% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 13.9% | 14.2% | 13.5% |

The estimated population of the parish of Ightham in 1660 was 325 and this approximately doubled to 709 by the first national census in 1801.[2]

At the 2001 UK census, the Ightham electoral ward had a population of 1,940. The ethnicity was 99.1% White, 0% Mixed Race, 0.6% Asian, 0.3% Black and 0% Other. The place of birth of residents was 91.9% United Kingdom, 0.5% Republic of Ireland, 2% other Western European countries, and 5.6% elsewhere. Religion was recorded as 82.4% Christian, 0.2% Buddhist, 0% Hindu, 0% Sikh, 0.5% Jewish, and 0.2% Muslim. 11.6% were recorded as having no religion, 0.4% had an alternative religion and 4.7% did not state their religion.[3]

The economic activity of residents aged 16–74 was 38.2% in full-time employment, 11.6% in part-time employment, 14.7% self-employed, 1.9% unemployed, 1.9% students with jobs, 3.5% students without jobs, 13.9% retired, 11.2% looking after home or family, 1.1% permanently sick or disabled and 1.9% economically inactive for other reasons. The industry of employment of residents was 12.3% retail, 9.4% manufacturing, 7.2% construction, 18.3% real estate, 8.2% health and social work, 8.3% education, 4.3% transport and communications, 3.2% public administration, 4.3% hotels and restaurants, 17.9% finance, 1.3% agriculture and 5.3% other. Compared with national figures, the ward had a relatively high proportion of workers in finance and real estate. There were a relatively low proportion in manufacturing, public administration, transport and communications. Of the ward's residents aged 16–74, 35.7% had a higher education qualification or the equivalent, compared with 19.9% nationwide.[3]

Nearest settlements

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- William Sutton (1830 – 1888), recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Benjamin Harrison (1837–1921), a grocer who won international recognition as a pioneer in the realm of archaeology. He contended that flints he found in the pre-glacial drift on the North Downs near Ash were artefacts, thus vastly antedating the antiquity of man.

- William Lambarde, author of the first English county history, A Perambulation of Kent, married his first wife, Jane, in 1570 at Ightham Church on her 17th birthday.[4] They then lived at the family home of the Manor of St Clere. Jane died on 21 September 1573, but William continued to live at the house for another 10 years.[5]

- Lord Eversley (when Mr. George John Shaw-Lefevre), and his wife, Constance, lived at Oldbury Place in Ightham during the time he was Postmaster General.[6]

- Anna Lee, MBE (2 January 1913 – 14 May 2004), was a British-born American actress.

- Thomas Riversdale Colyer-Fergusson, VC (18 February 1896 – 31 July 1917) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross. His Victoria Cross is displayed in the chapel at Ightham Mote.

- William Tomkin (25 November 1860 – 7 April 1940), British watercolour artist, draughtsman and Assistant to General Augustus Pitt Rivers. Along with other family members he is buried in the village churchyard.

- Cheryl Baker singer with The Fizz and TV presenter lives in the village.

- Martina Cole (born 30 March 1959), novelist. Has lived in the village since 2005.[7]

- Len Goodman - (1944 - 2023) - TV presenter

- Roger K. Furse - (1903–1972) - costume designer

References

[edit]- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ightham at the Crossroads by Jean Stirk and David Williams published by Red Court Publishing, copyright Ightham Parish Council, Jean Stirk and David Williams, 2015. ISBN 978-0-9930828-0-1

- ^ a b "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Historic Kent - Villages and Towns". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ Cameron, Roderick (1981). Great Comp and its garden. London: Bachman and Turner Publications. pp. 131–144. ISBN 0859741001.

- ^ Picton W. and Stirk J., Life in Ightham in the 1800s (Directwish Limited, 1989)

- ^ Cadwalla, Carole (30 May 2009). "The Booker prize money wouldn't even keep me in cigarettes". The Observer. Retrieved 18 November 2019.