Iver Johnson

| |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Manufacturing |

| Predecessor | Johnson Bye & Company |

| Founded | 1871 |

| Founder | Iver Johnson and Martin Bye |

| Defunct | 1993 |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

| Products | firearms, bicycles, and motorcycles |

| Parent | American Military Arms Corp |

Iver Johnson was an American firearms, bicycle, and motorcycle manufacturer from 1871 to 1993. The company shared the same name as its founder, Norwegian-born Iver Johnson (1841–1895).

The name was resold, and Iver Johnson Arms opened in 2006, but since it does not manufacture parts or provide information relating to the pre-1993 company, it represents a continuation of it in name only.[1]

Iver Johnson

[edit]

Iver Johnson was born in 1841[2] in Nordfjord, Sogn og Fjordane county, Norway.[3] He was educated as a gunsmith in Bergen in 1857, and had a gun store in Oslo. Johnson emigrated from Norway to Worcester, Massachusetts, United States in 1863, and continued his work as a gunsmith by trade and an inventor in his spare time. Seeking new and creative uses for his partially idle manufacturing equipment after the American Civil War, he worked not only gunsmithing locally in Fitchburg, but also providing designs and work to other firearms companies; notably making pepper-box pistols for Allen & Wheelock.[4][clarification needed]

On April 9, 1868, Johnson married Mary Elizabeth (née Speirs, born January 1847) in Worcester;[5][6][7][8] and the couple had three sons and two daughters.

Johnson Bye & Company

[edit]In 1871, Johnson merged his and Martin Bye's gunsmithing operations to form the Johnson Bye & Company. Beginning in 1876, Johnson and Bye filed jointly for, and received, multiple new firearms features and firearms feature improvement patents. Their primary revenues came from the sale of their self designed and manufactured inexpensive models of revolvers.[9]

The company's name changed to Iver Johnson & Company in 1883, upon Johnson's purchase of Bye's interest, but Bye continued working in the firearm industry for the remainder of his life.[9]

Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works

[edit]The company's name changed again to Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works in 1891, when the company relocated to Fitchburg, Massachusetts, (sometimes incorrectly referred to as "Fitzburg") in order to have better and larger manufacturing facilities. The company attracted a number of talented immigrant machinists and designers to its ranks, including O.F. Mossberg and Andrew Fyrberg, who would go on to invent the company's top-latching strap mechanism and the Hammer-the-Hammer transfer bar safety system used on the company's popular line of top-break safety revolvers.[10][11]

Iver Johnson died of tuberculosis in 1895,[2] and his sons took over the business. Frederick Iver, (born 10/2/1871),[6][7][8][12] John Lovell (born 6/26/1876),[6][7][8][13][14] and Walter Olof (born August 1878),[6][7][8] each had vastly different levels of involvement in the company ranging from executive leadership to barely any involvement at all. They shepherded the company through a phase of expansion, as bicycle operations grew, then converted to motorcycle manufacturing and sales. They also saw the growth of the firearms business and the eventual restructuring of the company to focus on firearms and related business as they divested non-firearms concerns, such as the motorcycle business, in the face of growing firearms demand, World War I's armaments industry expansion, and other factors. As family ownership waned and outside investment via publicly traded stock and mergers/acquisitions/partnerships took hold, the company changed ownership and moved several times during its operation.[15]

The company eventually dropped "Cycle Works" from its name when that part of the business was shut down. The business successfully weathered the Great Depression (in part thanks to higher rates of armed robbery, which helped maintain demand for personal firearms) and was buoyed by the dramatic increase in the market for arms leading up to and during World War II.[15]

After World War II, the company's introduction of new firearms slowed to a trickle. Increasingly, company fortunes depended upon sales of its increasingly outmoded revolvers and single-barrel shotguns. Without new research and development, most firearms changes were limited to cosmetic updates of existing designs.[15]

As a result of changes in ownership, the company had the first of two major relocations in 1971 when it moved to New Jersey. It moved again to Jacksonville, Arkansas, and was jointly owned by Lynn Lloyd and Lou Imperato, who also owned the Henry brand name, before it finally ceased trading under its own name in 1993, at which time it was owned by American Military Arms Corporation (AMAC).[16]

Iver Johnson firearm models

[edit]

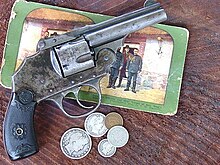

Iver Johnson nomenclature refers to its top-break revolvers as Safety Automatics. The term "Safety Automatic" refers to Iver Johnson's Hammer-the-Hammer transfer bar safety system ("safety") and the automatic ejection of cartridges upon breaking open the revolvers ("automatic").[9]

Lovell Swift Hammer & Hammerless

[edit]This model was made from 1890 to 1894 by Iver Johnson and distributed by John P. Lovell Arms Company of Boston, Massachusetts. It was a double action 5-shot revolver in caliber .38 S&W. It had a nickel finish and was the first Iver Johnson to use the owl's head logo on the grips. In appearance, the Swift model resembles the Safety Automatic Revolver that was introduced in 1894. Some differences include the latch for unlocking the frame pulls down rather than up, the ejector is different, and the Swift model does not have the "hammer the hammer action" of later models. The gun fired a .38 S&W black powder cartridge, and is not safe to shoot with modern smokeless powder cartridges. The hammerless model differed from the hammer model in that it did not have an external hammer protruding from the gun, and it had the addition of a manual safety on the trigger. This feature required the user to place a finger squarely on the trigger to fire the gun.[17] It has the word "Swift" engraved on the top of the gun, and the serial number is stamped under the left grip panel.

Safety automatic

[edit]Standard models with external hammer:

- First Model (1894–1895), single post latch system

- Second Model (1896–1908), double post latch system

- Third Model (1909–1941), double post latch system, adapted for smokeless powder

Safety automatic hammerless

[edit]- First Model (1895–1896), single post latch

- Second Model (1897–1908), safety lever added to face of trigger

- Third Model (a.k.a. "New Model") (1909–1941), no safety lever on trigger, adapted for smokeless powder

Assassinations

[edit]William McKinley assassination

[edit]On September 6, 1901, American steelworker and anarchist Leon Czolgosz shot US President William McKinley at the Temple of Music in Buffalo, New York, with an Iver Johnson .32 caliber Safety Automatic revolver. McKinley died eight days later. The revolver is on display at the Buffalo History Museum in Buffalo.[18]

Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted assassination

[edit]In 1933, Giuseppe Zangara shot and killed Chicago mayor Anton Cermak at a political event in Miami, in an apparent attempt to assassinate president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. Zangara was using a .32 revolver by the United States Revolver Company, a subsidiary of Iver Johnson.[19]

Robert Kennedy assassination

[edit]Jordanian Sirhan Sirhan assassinated presidential candidate United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy with an eight-shot Iver Johnson Cadet 55-A revolver chambered in .22 Long Rifle at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California, on June 5, 1968; Kennedy died the following day at Good Samaritan Hospital.[20] The revolver, as well as the official police files, reports, interviews, ballistics reports, bullet fragments, and other important evidence related to Kennedy's assassination, is housed in the California State Archives in Sacramento.[21]

Bicycles

[edit]

Iver Johnson bicycles are classic examples of early American bicycles, and during the bicycle boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the company had a very productive bicycle manufacturing and sales line of business. Iver Johnsons are considered to be "classics" by vintage bicycle collectors, and are considered especially pleasing from an aesthetic point of view. O.F. Mossberg worked in the bicycle plant and then started his own firearms factory.[11]

Even when they were new, I-J's were marketed and had a reputation for being very graceful looking, well built, and engineered for performance. Iver Johnson sponsored the career of bicycle racing champion Major Taylor beginning in 1900.[22] One 1924 I-J model had a truss-bridge frame which featured a curved tube under the top tube to strengthen the frame for use on the rough roads of the early twentieth century.[23] Bicycle production ceased in 1940 with the buildup of arms production prior to World War II.[15]

Iver Johnson bicycles are highly collectible, sought after, and relatively rare compared to most other major manufacturer's products from that time. As of 1974[update] an Iver Johnson bicycle is on display at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in the America on the Move exhibit.[24]

Motorcycles

[edit]

Launched in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, in 1907, The Iver Johnson Company motorcycle division was born from the conversion of a line of business that had been manufacturing bicycles for some 23 years prior to that point. Ultimately, the arms division of the business was growing so rapidly to meet demand that management decided to focus on that market and as a result motorcycle operations closed in 1916 (varying sources claim the last year as being 1915, with 1916 seeing only the sales of remaining 1915 produced inventory), bringing to an end 33 years of total cycle operations (23 for bicycles, and another 10 for motorcycle and run-off bicycle business).[25]

According to Roland Brown's History of the Motorcycle, Iver Johnson advertised their machines as "Mechanical Perfection", a boast that was not entirely unbelievable given the number of advanced design features in especially their later models, such as dual crankshafts, nickel-alloy machined parts, chain drive, and a hand-operated three-speed gearbox. Among collectors and researchers who have the benefit of hindsight, Iver-Johnsons, such as the 1915 Model 15-7, along with Scotts, are the finest examples of motorcycle engineering of that era.[26]

Revival of Iver Johnson name

[edit]In 2006, the name was reused as Iver Johnson Arms Incorporated in Florida as a manufacturer and importer of firearms (from other manufacturers based in Philippines, Turkey and Belgium), including 1911-style semi-automatic pistols unrelated to the old Iver Johnson lines.[27] The firm was renamed from Squires Bingham International, founded in 1973.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ "Iver Johnson Arms". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Massachusetts deaths, 1841-1915". Familysearch.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, 1872 October 30, Index to New England Naturalization Petitions, 1791-1906, serial M1299, roll 79.

- ^ The Story of Allen & Wheelock Firearms. H. H. Thomas, author. Pioneer Press, Incorporated. 1991)

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, 1870, August 18. 1870 U.S. census, population schedules: Worcester Ward 4, Worcester, Massachusetts, roll M593_658: p. 223B: image 483: lines 13-20.

- ^ a b c d National Archives and Records Administration, 1880, June 8. 1880 U.S. census, population schedules: Worcester, Worcester, Massachusetts, roll 567: p. 122D: enumeration district 884: image 0542: lines 22-27.

- ^ a b c d National Archives and Records Administration, 1900, June 6. 1900 U.S. census, population schedules: Fitchburg Ward 2, Worcester, Massachusetts, roll T623_691: p. 9A: enumeration district: 1609: lines 13-14 & 20-23.

- ^ a b c d National Archives and Records Administration, 1910, April 25. 1910 U.S. census, population schedules: Fitchburg Ward 2, Worcester, Massachusetts, roll T624_628: p. 10A: enumeration district 1728: image: 158: lines 70-76.

- ^ a b c Hogg, Ian; Walter, John (29 August 2004). Pistols of the World. David & Charles. pp. 183–185. ISBN 0-87349-460-1.

- ^ I. Johnson & O. Mossberg, U.S. Patent No. 511,620, Dec. 26, 1893

- ^ a b "The Mossberg Story". Gun Digest (17 ed.). Chicago: The Gun Digest Co. 1963. pp. 120–124.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, 1902, May 27. Passport Applications, 1795–1905: Suffolk County, Massachusetts, roll M1372, application #57156.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, 1904, January 18. Passport Applications, 1795–1905: Suffolk County, Massachusetts, roll M1372, application #81238.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration, 1918, September 12. United States, Selective Service System, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918: Fitchburg, Worcester, Massachusetts, roll 1685193.

- ^ a b c d Fjestad, S. P. (1 April 2008). Blue Book of Gun Values. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-886768-75-8.

- ^ "Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works Inc. (Direct Investments, Ltd.)". Archived from the original on 2009-07-03. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ^ Massey, Brian L. (2015). Iver Johnson Handguns 1871-1941, p. 36-37. ISBN 978-0-9940751-1-6

- ^ "Collections Highlights". Buffalo History Museum.

- ^ Robert Sherrill (February 1975). The Saturday night special: and other guns with which Americans won the West, protected bootleg franchises, slew wildlife, robbed countless banks, shot husbands purposely and by mistake, and killed presidents--together with the debate over continuing same. Penguin Books. p. 167. ISBN 9780140040098.

- ^ Moldea, Dan E. (1995). The Killing of Robert F. Kennedy: An Investigation of Motive, Means, and Opportunity. W.W. Norton. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-393-03791-3.

- ^ LLC, Filiquarian Publishing; Investigation, Federal Bureau of (2007). Robert F. Kennedy Assassination: The FBI Files. Filiquarian Publishing, LLC. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-59986-254-5.

- ^ Brill, Marlene Targ (1 September 2007). Marshall "Major" Taylor: World Champion Bicyclist, 1899-191. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8225-6610-6.

- ^ "Popular Science". The Popular Science Monthly. Bonnier Corporation: 135. December 1924. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ School Media Quarterly. Vol. 3. American Association of School Librarians. 1974. p. 166.

- ^ Hatfield, Jerry (8 February 2006). Standard Catalog of American Motorcycles 1898-1981: The Only Book to Fully Chronicle Every Bike Ever Built. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. pp. 362–363. ISBN 0-87349-949-2.

- ^ Brown, Roland (2004). History of the Motorcycle: From the First Motorized Bicycles to the Powerful and Sophisticated Superbikes of Today. Parragon. ISBN 978-1-4054-3952-7.

- ^ http://iverjohnsonarms.com/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Iver Johnson Arms".

Other sources

[edit]- Goforth, W.E. Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works Firearms 1871-1993 (Gun Show Books Publishing. 2006) ISBN 978-0-9787086-0-3

- Thomas, H. H. The Story of Allen & Wheelock Firearms (Pioneer Press, Incorporated. 1991) ISBN 978-0-913150-73-3

External links

[edit]- Iver Johnson firearms - armscollectors.com

- Iver Johnson Firearms Co

- Manufacturing companies established in 1871

- Defunct firearms manufacturers of the United States

- Motorcycle manufacturers of the United States

- Manufacturing companies disestablished in 1993

- Privately held companies based in Arkansas

- 1871 establishments in Massachusetts

- 1993 disestablishments in Arkansas

- Defunct manufacturing companies based in Arkansas