Ivan Krylov

Ivan Krylov | |

|---|---|

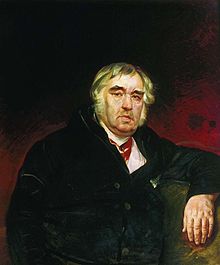

Portrait of Krylov by Karl Briullov, 1839 | |

| Native name | Ива́н Крыло́в |

| Born | Ivan Andreyevich Krylov 13 February 1769 Moscow |

| Died | 21 November 1844 (aged 75) St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Tikhvin Cemetery, Alexander Nevsky Lavra |

| Pen name | Navi Volyrk |

| Occupation | Poet, fabulist, playwright, novelist, journalist, publisher, translator |

| Language | Russian |

| Citizenship | |

| Genre | The fable, play, poetry, prose |

| Years active | 1786-1843 |

| Notable awards | Order of Saint Stanislaus (Imperial House of Romanov), Order of Saint Anna |

Ivan Andreyevich Krylov (Russian: Ива́н Андре́евич Крыло́в; 13 February 1769 – 21 November 1844) is Russia's best-known fabulist and probably the most epigrammatic of all Russian authors.[1] Formerly a dramatist and journalist, he only discovered his true genre at the age of 40. While many of his earlier fables were loosely based on Aesop's and La Fontaine's, later fables were original work, often with a satirical bent.

Life

[edit]

Ivan Krylov was born in Moscow, but spent his early years in Orenburg and Tver. His father, a distinguished military officer, resigned in 1775 and died in 1779, leaving the family destitute. A few years later Krylov and his mother moved to St. Petersburg in the hope of securing a government pension. There, Krylov obtained a position in the civil service, but gave it up after his mother's death in 1788.[2] His literary career began in 1783, when he sold to a publisher the comedy "The coffee-grounds fortune teller" (Kofeynitsa) that he had written at 14, although in the end it was never published or produced. Receiving a sixty ruble fee, he exchanged it for the works of Molière, Racine, and Boileau and it was probably under their influence that he wrote his other plays, of which his Philomela (written in 1786) was not published until 1795.

Beginning in 1789, Krylov also made three attempts to start a literary magazine, although none achieved a large circulation or lasted more than a year. Despite this lack of success, their satire and the humour of his comedies helped the author gain recognition in literary circles. For about four years (1797–1801) Krylov lived at the country estate of Prince Sergey Galitzine, and when the prince was appointed military governor of Livonia, he accompanied him as a secretary[2] and tutor to his children, resigning his position in 1803. Little is known of him in the years immediately after, other than the commonly accepted myth that he wandered from town to town playing cards.[2] By 1806 he had arrived in Moscow, where he showed the poet and fabulist Ivan Dmitriev his translation of two of Jean de La Fontaine's Fables, "The Oak and the Reed" and "The Choosy Bride", and was encouraged by him to write more. Soon, however, he moved on to St Petersburg and returned to play writing with more success, particularly with the productions of "The Fashion Shop" (Modnaya lavka) and "A Lesson For the Daughters" (Urok dochkam). These satirised the nobility's attraction to everything French, a fashion he detested all his life.

Krylov's first collection of fables, 23 in number, appeared in 1809 and met with such an enthusiastic reception that thereafter he abandoned drama for fable-writing. By the end of his career he had completed some 200, constantly revising them with each new edition. From 1812 to 1841 he was employed by the Imperial Public Library, first as an assistant, and then as head of the Russian Books Department, a not very demanding position that left him plenty of time to write. Honours were now showered on him in recognition of his growing reputation: the Russian Academy of Sciences admitted him as a member in 1811, and bestowed on him its gold medal in 1823; in 1838 a great festival was held in his honour under imperial sanction, and the Emperor Nicholas, with whom he was on friendly terms, granted him a generous pension.[2]

After 1830 he wrote little and led an increasingly sedentary life. A multitude of half-legendary stories were told about his laziness, his gluttony and the squalor in which he lived, as well as his witty repartee. Towards the end of his life Krylov suffered two cerebral hemorrhages and was taken by the Empress to recover at Pavlovsk Palace. After his death in 1844, he was buried beside his friend and fellow librarian Nikolay Gnedich in the Tikhvin Cemetery.[3]

Artistic heritage

[edit]Portraits of Krylov began to be painted almost as soon as the fame of his fables spread, beginning in 1812 with Roman M. Volkov's somewhat conventional depiction of the poet with one hand leaning on books and the other grasping a quill as he stares into space, seeking inspiration. Roughly the same formula was followed in the 1824 painting of him by Peter A. Olenin (1794 —1868) and that of 1834 by Johann Lebrecht Eggink. An 1832 study by Grigory Chernetsov groups his corpulent figure with fellow writers Alexander Pushkin, Vasily Zhukovsky and Nikolay Gnedich. This was set in the Summer Garden, but the group, along with many others, was ultimately destined to appear in the right foreground of Chernetsov's immense "Parade at Tsaritsyn Meadow", completed in 1837.

In 1830 the sculptor Samuil Galberg carved a portrait bust of Krylov. It may have been this or another that was presented by the Emperor to his son Alexander as a new year's gift in 1831.[4] A bust is also recorded as being placed on the table before Krylov's seat at the anniversary banquet held in his honour in 1838.[5] The most notable statue of him was placed in the Summer Garden (1854–55) ten years after his death. Regarded as a sign of the progress of Romanticism in Russian official culture, it was the first monument to a poet erected in Eastern Europe. The sculptor Peter Clodt seats his massive figure on a tall pedestal surrounded on all sides by tumultuous reliefs designed by Alexander Agin that represent scenes from the fables.[6] Shortly afterwards, he was included among other literary figures on the Millennium of Russia monument in Veliky Novgorod in 1862.[7]

Later monuments chose to represent individual fables separately from the main statue of the poet. This was so in the square named after him in Tver, where much of his childhood was spent. It was erected on the centenary of Krylov's death in 1944 and represents the poet standing and looking down an alley lined with metal reliefs of the fables mounted on plinths.[8] A later monument was installed in the Patriarch's Ponds district of Moscow in 1976. This was the work of Andrei Drevin, Daniel Mitlyansky, and the architect A. Chaltykyan. The seated statue of the fabulist is surrounded by twelve stylised reliefs of the fables in adjoining avenues.[9]

Krylov shares yet another monument with the poet Alexander Pushkin in the city of Pushkino's Soviet Square.[10] The two were friends and Pushkin modified Krylov's description of 'an ass of most honest principles' ("The Ass and the Peasant") to provide the opening of his romantic novel in verse, Eugene Onegin. So well known were Krylov's fables that readers were immediately alerted by its first line, 'My uncle, of most honest principles'.[11]

Some portraits of Krylov were later used as a basis for the design of commemorative stamps. The two issued in 1944 on the centenary of his death draw on Eggink's,[12] while the 4 kopek stamp issued in 1969 on the bicentenary of his birth is indebted to Briullov's late portrait. The same portrait is accompanied by an illustration of his fable "The wolf in the kennel" on the 40 kopek value in the Famous Writers series of 1959. The 150th anniversary of Krylov's death was marked by the striking of a two ruble silver coin in 1994.[13] He is also commemorated in the numerous streets named after him in Russia as well as in formerly Soviet territories.

-

Portrait of Ivan Krylov by Roman Maximovich Volkov (1812)

-

Parade at Tsaritsyn Meadow by Gregory Chernetsov (detail)

-

Ivan Krylov by Peter A. Olenin (1824)

-

by Johann Lebrecht Eggink (1834)

-

Stamp by Vasili Vasilievich Zavyalov (1959)

The Fables

[edit]As literature

[edit]By the time of Krylov's death, 77,000 copies of his fables had been sold in Russia, and his unique brand of wisdom and humor has remained popular ever since. His fables were often rooted in historic events and are easily recognizable by their style of language and engaging story. Though he began as a translator and imitator of existing fables, Krylov soon showed himself an imaginative, prolific writer, who found abundant original material in his native land and in the burning issues of the day.[2] Occasionally this was to lead into trouble with the Government censors, who blocked publication of some of his work. In the case of "The Grandee" (1835), it was only allowed to be published after it became known that Krylov had amused the Emperor by reading it to him,[14] while others did not see the light until long after his death, such as "The Speckled Sheep", published in 1867,[15] and "The Feast" in 1869.[16]

Beside the fables of La Fontaine, and one or two others, the germ of some of Krylov's other fables can be found in Aesop, but always with his own witty touch and reinterpretation. In Russia his language is considered of high quality: his words and phrases are direct, simple and idiomatic, with color and cadence varying with the theme,[2] many of them becoming actual idioms. His animal fables blend naturalistic characterization of the animal with an allegorical portrayal of basic human types; they span individual foibles as well as difficult interpersonal relations.

Many of Krylov's fables, especially those that satirize contemporary political situations, take their start from a well-known fable but then diverge. Krylov's "The Peasant and the Snake" makes La Fontaine's The Countryman and the Snake (VI.13) the reference point as it relates how the reptile seeks a place in the peasant's family, presenting itself as completely different in behaviour from the normal run of snakes. To Krylov's approbation, with the ending of La Fontaine's fable in mind, the peasant kills it as untrustworthy. The Council of the Mice uses another fable of La Fontaine (II.2) only for scene-setting. Its real target is cronyism and Krylov dispenses with the deliberations of the mice altogether. The connection between Krylov's "The Two Boys"[17] and La Fontaine's The Monkey and the Cat is even thinner. Though both fables concern being made the dupe of another, Krylov tells of how one boy, rather than picking chestnuts from the fire, supports another on his shoulders as he picks the nuts and receives only the rinds in return.

Fables of older date are equally laid under contribution by Krylov. The Hawk and the Nightingale is transposed into a satire on censorship in "The Cat and the Nightingale"[18] The nightingale is captured by a cat so that it can hear its famous song, but the bird is too terrified to sing. In one of the mediaeval versions of the original story, the bird sings to save its nestlings but is too anxious to perform well. Again, in his "The Hops and the Oak",[19] Krylov merely embroiders on one of the variants of The Elm and the Vine in which an offer of support by the tree is initially turned down. In the Russian story, a hop vine praises its stake and disparages the oak until the stake is destroyed, whereupon it winds itself about the oak and flatters it.

Establishing the original model of some fables is problematical, however, and there is disagreement over the source for Krylov's "The swine under the oak".[20] There, a pig eating acorns under an oak also grubs down to the roots, not realising or caring that this will destroy the source of its food. A final verse likens the action to those who fail to honour learning although benefitting from it. In his Bibliographical and Historical Notes to the fables of Krilof (1868), the Russian commentator V.F.Kenevich sees the fable as referring to Aesop's "The Travellers and the Plane Tree". Although that has no animal protagonists, the theme of overlooking the tree's usefulness is the same. On the other hand, the French critic Jean Fleury points out that Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s fable of "The Oak Tree and the Swine",[21] a satirical reworking of Aesop's "The Walnut Tree", is the more likely inspiration, coalescing as it does an uncaring pig and the theme of a useful tree that is maltreated.[22]

In the arts

[edit]In that some of the fables were applied as commentaries on actual historical situations, it is not surprising to find them reused in their turn in political caricatures. It is generally acknowledged that "The wolf in the kennel" is aimed at the French invasion of Russia in 1812, since the Emperor Napoleon is practically quoted in a speech made by the wolf.[23] This was shortly followed up by the broadsheet caricature of Ivan Terebenev (1780–1815), titled "The wolf and the shepherd", celebrating Russia's resistance.[24] The fable of "The swan, the pike and the crawfish", all of them pulling a cart in a different direction, originally commented sceptically on a new phase in the campaign against Napoleon in the coalition of 1814 (although some interpreters tend to see it as an allusion to the endless debates of the State Council[25]). It was reused for a satirical print in 1854 with reference to the alliance between France, Britain and Turkey at the start of the Crimean War.[26] Then in 1906 it was applied to agricultural policy in a new caricature.[27]

The fables have appeared in a great variety of formats, including as illustrations on postcards and on matchbox covers.[28]). The four animals from the very popular "The Quartet" also appeared as a set, modeled by Boris Vorobyov for the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory in 1949.[29] This was the perfect choice of subject, since the humour of Krylov's poem centres on their wish to get the seating arrangement right as an aid to their performance. The format therefore allows them to be placed in the various positions described in the fable.

Not all the fables confined themselves to speaking animals and one humorous human subject fitted the kind of genre paintings of peasant interiors by those from the emerging Realist school. This scenario was "Demyan's Fish Soup", in which a guest is plied with far more than he can eat. Two of those who took the subject up were Andrei M.Volkov (1829-1873) in 1857,[30] and Andrei Popov (1832–1896) in 1865 (see left). Another fable, originally adapted from La Fontaine's "La Fille", was Krylov's "The Dainty Spinster", which lent itself to the social satire of Pavel Fedotov's painting of 1847. That depicts the aging maid accepting the proposal of a balding, hunchbacked suitor who kneels at her feet, while her anxious father listens behind a curtained doorway. In 1976, the painting was featured on a Soviet postage stamp.

Illustrated books of Krylov's fables have continued in popularity and at the start of the 20th century the styles of other new art movements were applied to the fables. In 1911 Heorhiy Narbut provided attractive Art Nouveau silhouettes for 3 Fables of Krylov, which included "The beggar and fortune" (see below) and "Death and the peasant". A decade later, when the artistic avant-garde was giving its support to the Russian Revolution, elements of various schools were incorporated by Aleksandr Deyneka into a 1922 edition of the fables. In "The cook and the cat" it is Expressionism,[31] while the pronounced diagonal of Constructivism is introduced into "Death and the peasant".[32]

When Socialist realism was decreed shortly afterwards, such experiments were no longer possible. However, "Demyan's Fish Soup" reappears as a suitable peasant subject in the traditional Palekh miniatures of Aristarkh A.Dydykin (1874 - 1954). Some of these was executed in bright colours on black lacquered papier-mâché rondels during the 1930s,[33] but prior to that he had decorated a soup plate with the same design in different colours. In this attractive 1928 product the action takes place in three bands across the bowl of the dish, with the guest taking flight in the final one. With him runs the cat which was rubbing itself against his leg in the middle episode. About the rim jolly fish sport tail to tail.[34]

Musical settings

[edit]Musical adaptations of the fables have been more limited. In 1851, Anton Rubinstein set 5 Krylov Fables for voice and piano, pieces republished in Leipzig in 1864 to a German translation. These included "The quartet", "The eagle and the cuckoo", "The ant and the dragonfly", "The ass and the nightingale", and "Parnassus". He was followed by Alexander Gretchaninov, who set 4 Fables after Ivan Krylov for medium voice and piano (op.33), which included "The musicians", "The peasant and the sheep", "The eagle and the bee", and "The bear among the bees". This was followed in 1905 by 2 Fables after Krylov for mixed a cappella choir (op.36), including "The frog and the ox" and "The swan, the pike and the crayfish". At about this time too, Vladimir Rebikov wrote a stage work titled Krylov's Fables and made some settings under the title Fables in Faces (Basni v litsach) that are reported to have been Sergei Prokofiev’s model for Peter and the Wolf.[35]

In 1913, Cesar Cui set 5 Fables of Ivan Krylov (Op.90) and in 1922 the youthful Dmitri Shostakovich set two by Krylov for solo voice and piano accompaniment (op.4), "The dragonfly and the ant" and "The ass and the nightingale".[36] The dragonfly, a ballet based on the first of these fables, was created by Leonid Yakobson for performance at the Bolshoi in 1947 but it was withdrawn at the last moment due to political infighting.[37]

The Russian La Fontaine

[edit]

Krylov is sometimes referred to as 'the Russian La Fontaine' because, though he was not the first of the Russian fabulists, he became the foremost and is the one whose reputation has lasted, but the comparison between the two men can be extended further. Their fables were also the fruit of their mature years; they were long meditated and then distilled in the language and form most appropriate to them. La Fontaine knew Latin and so was able to consult classical versions of Aesop's fables in that language – or, as in the case of "The Banker and the Cobbler", to transpose an anecdote in a poem by Horace into his own time. Krylov had learned French while still a child and his early work followed La Fontaine closely. Though he lacked Latin, he taught himself Koine Greek from a New Testament in about 1819,[38] and so was able to read Aesop in the original rather than remaining reliant on La Fontaine's recreations of Latin versions. The major difference between them, however, was that La Fontaine created very few fables of his own, whereas the bulk of Krylov's work after 1809 was either indebted to other sources only for the germ of the idea or the fables were of his invention

Krylov's first three fables, published in a Moscow magazine in 1806, followed La Fontaine's wording closely; the majority of those in his 1809 collection were likewise adaptations of La Fontaine. Thereafter he was more often indebted to La Fontaine for themes, although his treatment of the story was independent. It has been observed that in general Krylov tends to add more detail in contrast with La Fontaine's leaner versions and that, where La Fontaine is an urbane moralist, Krylov is satirical.[39] But one might cite the opposite approach in Krylov's pithy summation of La Fontaine's lengthy "The Man who Runs after Fortune" (VII.12) in his own "Man and his shadow". Much the same can be said of his treatment of "The Fly and the Bee" (La Fontaine's The Fly and the Ant, IV.3) and "The Wolf and the Shepherds" (La Fontaine's X.6), which dispense with the circumstantiality of the original and retain little more than the reasoning.

The following are the fables that are based, with more or less fidelity, on those of La Fontaine:

1806

- The Oak and the Reed (I.22)

- The Choosy Bride (La Fontaine's The Maid, VII.5)

- The Old Man and the Three Young Men (XI.8)

1808

- The Dragonfly and the Ants (I.1)

- The Raven and the Fox (Aesop) (I.2)

- The Frog and the Ox (I.3)

- The Lion at the Hunt (I.6)

- The Wolf and the Lamb (I.10)

- The Peasant and Death (or the woodman in La Fontaine, I.16)

- The Fox and the Grapes (III.11)

- The Fly and the Travellers (VII.9)

- The Hermit and the Bear (VIII.10)

1809

- The Cock and the Pearl (I.20)

- The Lion and the Mosquito (II.9)

- The Frogs who Begged for a Tsar (III.4)

- The Man and the Lion (III.10)

- The Animals Sick of the Plague (VII.1)

- The Two Pigeons (IX.2)

1811

- The Young Crow (who wanted to imitate the eagle in La Fontaine, II.16)

- Gout and the spider (III.8)

- The Banker and the Cobbler (VIII.2)

1816

- The Wolf and the Crane (III.9)

- The Mistress and her Two Maids (V.6)

1819

- The Shepherd and the Sea (IV.2)

- The Greedy Man and the Hen (who laid golden eggs in La Fontaine, V.13)

1825

- The Lion Grown Old (III.14)

- The Kettle and the Pot (V.2)

- The Crow (La Fontaine's Jay in Peacock's Feathers, IV.9)

1834

- The Lion and the Mouse (II.11)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Janko Lavrin. Gogol. Haskell House Publishers, 1973. Page 6.

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kriloff, Ivan Andreevich". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 926–927.

- ^ "English: Ivan Krylov grave in Tikhvin Cemetery". September 16, 2007 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Coxwell, p.10

- ^ Ralston p.xxxviii

- ^ "Online details of the monument". Backtoclassics.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Russian Academic Dictionary

- ^ "033". March 15, 2014 – via Flickr.

- ^ "Walks in Moscow: Presnya | One Life Log". Onelifelog.wordpress.com. 2011-01-29. Retrieved 2013-04-22.; photographs of the reliefs appear on the Another City site Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "В Подмосковье ребёнок застрял в памятнике Крылову и Пушкину". Пикабу. 18 July 2018.

- ^ Levitt, Marcus (2006). "3". The Cambridge Companion to Pushkin (PDF). p. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ "<Stamps>". Archived from the original on 2017-11-27. Retrieved 2015-03-27.

- ^ "Coin: 2 Roubles (225 years I.A. Krylov) (Russia) (1992~Today – Numismatic Product: Famous People) WCC:y343". Colnect.com. 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Ralston, p.13

- ^ "Басни. Пестрые Овцы". krylov.lit-info.ru.

- ^ Ralston, p.248

- ^ Harrison, p.220

- ^ Ralston, pp.167–8

- ^ Harrison p.111

- ^ Harrison, pp.178-9

- ^ Fables and Epigrams of Lessing translated from the German, London 1825, Fable 33

- ^ Krylov et ses Fables, Paris 1869, pp.127-8

- ^ Ralston, p.15

- ^ Napoleon.org Archived 2013-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kriloff's original fables

- ^ Ralston, p.178

- ^ Bem, E. M. (June 28, 1906). "English: Political caricature" – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ There were matchbox series in Creighton University 1960[permanent dead link] and 1992 Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lomonosov Porcelain factory

- ^ "Russian museums".

- ^ "The Cook and the cat (illustration to the fable of Krylov) by Alexander Alexandrovich Deineka: History, Analysis & Facts". Arthive.

- ^ "Illustration for I. A. Krylov's fable "the Peasant and death" by Alexander Alexandrovich Deineka: History, Analysis & Facts". Arthive.

- ^ An example on the All Russia site

- ^ "State Museum of Palekh Art".

- ^ Georg von Albrecht, From Musical Folklore to Twelve-tone Technique, Scarecrow Press 2004, p.59

- ^ There is an analysis of these in The Exhaustive Shostakovitch and a complete performance on YouTube

- ^ Janice Ross, Like a bomb going off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia, Yale University 2015, pp.168–70

- ^ Ralston, p.xxxii

- ^ Bougeault, Alfred (1852). Kryloff, ou Le La Fontaine russe: sa vie et ses fables. Paris: Garnier frères. pp. 30–35.

References

[edit]- Translations, memoirs of the author and notes on the fables in English translation can be found in

- W.R.S.Ralston, Krilof and his Fables, prose translations and a memoir, originally published London 1869; 4th augmented edition 1883

- Henry Harrison, Kriloff’s Original Fables, London 1883,

- C.Fillingham Coxwell, Kriloff's Fables, translated into the original metres, London 1920

External links

[edit]- A limited preview with the introduction and five fables, The frogs who begged for a tsar and 61 other Russian fables, a verse translation by Lydia Rasran Stone, Monpelier VT 2010

- Works by or about Ivan Krylov at the Internet Archive

- Works by Ivan Krylov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire

- Male poets from the Russian Empire

- Members of the Russian Academy

- Full members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- 1769 births

- 1844 deaths

- Burials at Tikhvin Cemetery

- Writers from Moscow

- 18th-century writers from the Russian Empire

- 18th-century non-fiction writers from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century writers from the Russian Empire

- Journalists from the Russian Empire

- Male writers from the Russian Empire

- 18th-century male writers

- Russian fabulists

![Parade at Tsaritsyn Meadow [ru] by Gregory Chernetsov (detail)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Parade-5-Oct-1831---Gregory.png/90px-Parade-5-Oct-1831---Gregory.png)

![Ivan Krylov by Peter A. Olenin [ru] (1824)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Krylov_by_Olenin.jpg/89px-Krylov_by_Olenin.jpg)

![by Johann Lebrecht Eggink [de] (1834)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Ivan_Krylov_by_Eggink.jpg/89px-Ivan_Krylov_by_Eggink.jpg)

![Stamp by Vasili Vasilievich Zavyalov [ru] (1959)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/The_Soviet_Union_1959_CPA_2289_stamp_%28Ivan_Krylov_%28after_Karl_Bryullov%29_and_Scene_from_his_Works%29.jpg/120px-The_Soviet_Union_1959_CPA_2289_stamp_%28Ivan_Krylov_%28after_Karl_Bryullov%29_and_Scene_from_his_Works%29.jpg)