Islamic state

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

An Islamic state has a form of government based on sharia. As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world.[1] As a translation of the Arabic term dawlah islāmiyyah (Arabic: دولة إسلامية) it refers to a modern notion associated with Islamic governance.[2][3] Notable examples of historical Islamic states include the state of Medina, established by the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the Arab caliphates which continued under his successors, such as the Rashidun and Umayyads.

The concept of the modern Islamic state has been articulated and promoted by figures such as Sayyid Rashid Rida, Mulla Omar, Abul A'la Maududi, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Israr Ahmed, Sayyid Qutb and Hassan al-Banna. Implementation of Islamic law plays an important role in modern theories of the Islamic state, as it did in classical Islamic political theories. However, most of the modern theories also make use of notions that did not exist before the modern era.[1]

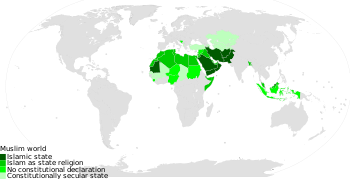

Today, many Muslim countries have incorporated Islamic law, wholly or in part, into their legal systems. Certain Muslim states have declared Islam to be their state religion in their constitutions, but do not apply Islamic law in their courts. Islamic states that are not Islamic monarchies are mostly Islamic republics.

Principles of Islamic states and collective decision-making (shura)

[edit]The guiding principle of an Islamic government is the concept of al-Shura, meaning 'consultation' or 'collective decision-making'. Muslim scholars are of the opinion that Islamic al-Shura should consist of work in the public interest, compliance with the Quran and Sunnah, democratic elections conducted within shura bodies, and majority rule within the bounds of Islamic law.[4]

Two of the biggest historical models used as determinants for practices relating to Islamic governance are the Constitution of Medina, which laid out peacetime administration of multi-religious municipalities during the time of Muhammad, and the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, which outlines the extent of concessions that can be made in battle.[5]

Among the accepted tenets of Islamic governance are monotheism, equality, freedom, civil conduct, accountability, and justice ('adl).[6]

Islamic states are generally obligated to maintain a free-market economic structure with restrictions only applicable to sharia non-compliant practices, such as gambling, fraud, usury, and the stimulant industry.[7] These states are required to generally administer zakat, obligatory charity, on a state-level for the purpose of wealth redistribution.[8]

Islamic states are also built around the idea of forbidding wrong and enjoining good, known as hisba in Arabic. This concept is core to Islamic social governance and the subsequent prohibition of adultery, rape, and incest in Islamic societies.[9]

Non-Muslim civilians classified under People of the Book have a right to parallel governance and military draft exemptions in exchange for jizya revenue.[10] Some Islamic states have opted to exempt non-Muslims from jizya under the condition of accepting the military draft.[11]

Muhammad himself respected the decision of the shura members. He is the champion of the notion of al-Shura, and this was illustrated in one of the many historical events, such as in the Battle of Khandaq (Battle of the Trench), where Muhammad was faced with two decisions, i.e. to fight the invading non-Muslim Arab armies outside of Medina or wait until they enter the city. After consultation with the sahabah (companions), it was suggested by Salman al-Farsi that it would be better if the Muslims fought the non-Muslim Arabs within Medina by building a big ditch on the northern periphery of Medina to prevent the enemies from entering Medina. This idea was later supported by the majority of the sahabah, and thereafter Muhammad also approved it.

Historical Islamic states

[edit]Majid Khadduri gives six stages of history for the Islamic state:[12]

- City-state (622–632)

- Imperial (632–750)

- Universal (c. 750–900)

- Decentralization (c. 900–1500)

- Fragmentation (c. 1500–1918)

- Nation states (1918–present)

Early Islamic governments

[edit]The first Islamic State was the political entity established by Muhammad in Medina in 622 CE under the Constitution of Medina. It represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah (nation). It was subsequently transformed into the caliphate by Muhammad's disciples, who were known as the Rightly Guided (Rashidun) Caliphs (632–661 CE). The Islamic State significantly expanded under the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) and consequently the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258).

Revival and abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate

[edit]The Ottoman Sultan, Selim I (1512–1520) reclaimed the title of caliph which had been in dispute and asserted by a diversity of rulers and shadow caliphs in the centuries of the Abbasid-Mamluk Caliphate since the Mongols' sacking of Baghdad and the killing of the last Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Iraq 1258.

The Ottoman Caliphate as an office of the Ottoman Empire was abolished under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1924 as part of Atatürk's Reforms. This move was most vigorously protested in India, as Mahatma Gandhi and Indian Muslims united behind the symbolism of the Ottoman Caliph in the Khilafat Movement which sought to reinstate the caliph deposed by Atatürk. The movement leveraged the Ottoman resistance against political pressure from Britain to abolish the caliphate, connecting it with Indian nationalism and the movement for independence from British rule. However, the Khilafat found little support from the Muslims of the Middle East themselves who preferred to be independent nation states rather than being under the Ottoman Turkish rule. In the Indian sub-continent, although Gandhi tried to co-opt the Khilafat as a national movement, it soon degenerated into a jihad against non-Muslims, also known as Moplah riots, with thousands being killed in the Malabar region of Kerala.[13]

Modern Islamic state

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

Development of the notion of dawla

[edit]The Arabic word dawla comes from the root d-w-l, meaning "to turn, come around in a cyclical fashion". In the Quran, it is used to refer to the nature of human fortunes, alternating between victory and defeat (3:140). This use led Arab writers to apply the word to succession of dynasties, particularly to the overthrow of the Umayyads of Damascus by the Abbasids.[14] The first Abbasid caliphs themselves spoke of "our dawla" in the sense of "our turn/time of success".[15] As Abbasids maintained their power, the dynastic sense of dawla became conflated with their dynastic rule,[14] and in later times al-Dawla was used across the Islamic world as a honorific title for rulers and high officials.[15]

Like their Christian contemporaries, pre-modern Muslims did not generally conceive of the state as an abstract entity distinct from the individual or group who held political power.[14] The word dawla and its derivatives began to acquire modern connotations in the Ottoman Empire and Iran in the 16th and 17th centuries in the course of diplomatic and commercial exchanges with Europe. During the 19th century, the Arabic dawla and Turkish devlet took on all the aspects of the modern notion of state while the Persian davlat can mean either state or government.[15]

Development of Modern Conception of Islamic state

[edit]According to Pakistani scholar of Islamic history Qamaruddin Khan, the term Islamic state "was never used in the theory or practice of Muslim political science, before the twentieth century".[16][17] Sohail H. Hashmi characterizes dawla Islamiyya as a neologism found in contemporary Islamist writings.[14] Islamic theories of the modern notion of state first emerged as a reaction to the abolition of the Ottoman caliphate in 1924. It was also in this context that the famous dictum that Islam is both a religion and a state (al-Islam din wa dawla) was first popularized.[1]

The modern conception of Islamic state was first articulated by the Syrian-Egyptian Islamic theologian Muḥammad Rashīd Riḍā (1865–1935). Rashid Rida condemned the 1922 Turkish Abolition of Sultanate which reduced the Khilafa into a purely spiritual authority; soon after the First World War. In his book al-Khilafa aw al-Imama al-Uzma (The Caliphate or the Grand Imamate) published in 1922, Rida asserted that the Caliphate should have the combined powers of both spiritual and temporal authority. He called for the establishment of an Islamic state led by Arabs, functioning as a khilāfat ḍurūrah (caliphate of necessity) that upholds Sharia, and defend its Muslim and non-Muslim subjects.[18]

Another important modern conceptualization of the Islamic state is attributed to Abul A'la Maududi (1903–1979), a Pakistani Muslim theologian who founded the political party Jamaat-e-Islami and inspired other Islamic revolutionaries such as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[19] Abul A'la Maududi's early political career was influenced greatly by anti-colonial agitation in India, especially after the tumultuous abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924 stoked anti-British sentiment.[20]

The Islamic state was perceived as a third way between the rival political systems of democracy and socialism (see also Islamic modernism).[21] Maududi's seminal writings on Islamic economics argued as early as 1941 against free-market capitalism and state intervention in the economy, similar to Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr's later Our Economics written in 1961. Maududi envisioned the ideal Islamic state as combining the democratic principles of electoral politics with the socialist principles of concern for the poor.[22]

Muslim world today

[edit]

Today, many Muslim countries have incorporated Islamic law in part into their legal systems. Certain Muslim states have declared Islam to be their state religion in their constitutions, but do not apply Islamic law in their courts. Islamic states which are not Islamic monarchies are usually referred to as Islamic republics,[23] such as the islamic republics of Iran,[24] Pakistan and Mauritania. Pakistan adopted the title under the constitution of 1956; Mauritania adopted it on 28 November 1958; and Iran adopted it after the 1979 Revolution that overthrew the Pahlavi dynasty. In Iran, the form of government is known as the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists. The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is run as an Islamic state by the Taliban government, which closely follows controversial Deobandi interpretations of Islamic law.

The Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration as of 3 August 2011 declared Islam to be the official religion of Libya.

Brunei

[edit]Brunei is an absolute Islamic monarchy. With the constitution in 1959, Islam became the official religion of the country.[25]

Iran

[edit]Leading up to the Iranian Revolution of 1979, many of the highest-ranking clergy in Shia Islam held to the standard doctrine of the Imamate, which allows political rule only by Muhammad or one of his true successors. They were opposed to creating an Islamic state (see Ayatollah Ha'eri Yazdi (Khomeini's own teacher), Ayatollah Borujerdi, Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari, and Grand Ayatollah Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei).[26] Contemporary theologians who were once part of the Iranian Revolution also became disenchanted and critical of the unity of religion and state in the Islamic Republic of Iran, are advocating secularization of the state to preserve the purity of the Islamic faith (see Abdolkarim Soroush and Mohsen Kadivar).[27]

Per Supreme leader, Islamic state is the 3rd phase of Iranian Islamic Republic program and is in and of itself part of New Islamic Civilization.[28]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]Saudi Arabia is an Islamic absolute monarchy. The Basic Law of Saudi Arabia contains many characteristics of what might be called a constitution in other countries. However, the Qur'an and the Sunnah is declared to be the official constitution of the country which is governed on the basis of Islamic law (Shari'a). The Allegiance Council is responsible to determine the new King and the new Crown Prince. All citizens of full age have a right to attend, meet, and petition the king directly through the traditional tribal meeting known as the majlis.[29]

Yemen

[edit]The Constitution of Yemen declares that Islam is the state religion, and that Shari'a (Islamic law) is the source of all legislation.

Mauritania

[edit]The Islamic Republic of Mauritania is a country in the Maghreb region of western North Africa.[30][31][32] Mauritania was declared an independent state as the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, on November 28, 1960.[33] The Constitutional Charter of 1985 declares Islam as the state religion and sharia the law of the land.

Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan was created as a separate state for Indian Muslims in British India in 1947, and followed the parliamentary form of democracy. In 1949, the first Constituent Assembly of Pakistan passed the Objectives Resolution which envisaged an official role for Islam as the state religion to make sure any future law should not violate its basic teachings. On the whole, the state retained most of the laws that were inherited from the British legal code that had been enforced by the British Raj since the 19th century. In 1956, the elected parliament formally adopted the name Islamic Republic of Pakistan, declaring Islam as the official religion.

Afghanistan

[edit]After the fall of Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (Soviet occupation), Afghanistan has gone through several attempts to set up an Islamic state:

- Islamic State of Afghanistan (1992–2002)

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (1996–2001)

- Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan (2002–2004)

- Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (2004–2021)

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (2021–present)

See also

[edit]- Syed Farid al-Attas

- Central Waqf Council

- Christian state

- Former Salafist states in Afghanistan

- Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist

- Halachic state – Jewish state governed by rabbinical law (halakha)

- Hizb ut-Tahrir

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

- Islamic Revolutionary State of Afghanistan

- Islamic State

- Islamic State of Azawad – a former short-lived unrecognised state declared unilaterally in 2012 by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad

- Islamic State of Indonesia – (Negara Islam Indonesia or Darul Islam), Islamist group in Indonesia that aims for the establishment of an Islamic state of Indonesia (an unrecognised state)

- Theocracy § Islamic theocracies

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ayubi, Nazih N.; Hashemi, Nader; Qureshi, Emran (2009). "Islamic State". In Esposto, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2019-07-15. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2014). "Islamic State". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-04-26. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

[Islamic State] Modern ideological position associated with political Islam.

- ^ Hashmi, Sohail H. (2004). "Dawla". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference.

One also finds in contemporary Islamist writings the neologism dawla Islamiyya, or Islamic state.

- ^ Jeong, Chun Hai; Nawi, Nor Fadzlina. (2007). Principles of Public Administration: An Introduction. Kuala Lumpur: Karisma Publications. ISBN 978-983-195-253-5.

- ^ Belhaj, Abdessamad (2024-12-23). "Political Loyalty in Reformist Islamic Ethics: Resources and Limits". American Journal of Islam and Society. 41 (3–4): 6–33. doi:10.35632/ajis.v41i3-4.3525. ISSN 2690-3741.

- ^ Abdul-Aziz, M. "The Principles of Islamic Polity in the Qur'an and Sunnah: Revisiting Modern Political Discourse". Al-Burhăn Journal of Qur'ān and Sunnah Studies.

- ^ Lewis, Mervyn K. (2014-12-26), "Principles of Islamic corporate governance", Handbook on Islam and Economic Life, Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 978-1-78347-982-5, retrieved 2025-01-05

- ^ "Economic Development and Islamic Finance". World Bank. 2013. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-9953-8.

- ^ Batchelor, Daud Abdulfattah. "Integrating Islamic Principles and Values into the Fabric of Governance". Islam and Civilisational Renewal. 5 (3): 351–374. doi:10.12816/0009867.

- ^ Alawiye, Habeebulah (2023-01-01). "Concept of Jizyah under Islamic Law and The Historical Factors Contributing to its Decline". Journal of Islamic Shariah.

- ^ "Religious Minorities Under Muslim Rule". Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research. Retrieved 2025-01-05.

- ^ Khadduri, Majid (1966). "Translator's Introduction". The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's Siyar. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 19-22.

- ^ Gail Minault, The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India (1982).

- ^ a b c d Hashmi, Sohail H. (2004). "Dawla". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference.

- ^ a b c Akhavi, Shahrough (2009). "Dawlah". In Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Khan, Qamaruddin (1982). Political Concepts in the Quran. Lahore: Islamic Book Foundation. p. 74.

The claim that Islam is a harmonious blend of religion and politics is a modern slogan, of which no trace can be found in the past history of Islam. The very term, "Islamic State" was never used in the theory or practice of Muslim political science, before the twentieth century. Also if the first thirty years of Islam were excepted, the historical conduct of Muslim states could hardly be distinguished from that of other states in world history.

- ^ Eickelman, D. F.; Piscatori, J. (1996). Muslim politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 53.

The Pakistani writer Qamaruddin Khan, for example, has proposed that the political theory of Islam does not arise from the Qur'an but from circumstances and that the state is neither divinely sanctioned nor strictly necessary as a social institution.

- ^ Ayubi, Nazih N.; Hashemi, Nader; Qureshi, Emran (2009). "Islamic State". In Esposto, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021.

- ^ Nasr, S. V. R. (1996). Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism. Chapter 4. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Minault, G. (1982). The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Kurzman, Charles (2002). "Introduction". Modernist Islam 1840-1940: A Sourcebook. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Khir, B. M. "The Islamic Quest for Sociopolitical Justice". In Cavanaugh, W. T.; Scott, P., eds. (2004). The Blackwell Companion to Political Theology. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 503–518.

- ^ Elliesie, Hatem. "Rule of Law in Islamic Modeled States" Archived 2019-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. In Koetter, Matthias; Shuppert, Gunnar Folke, eds. (2010). Understanding of the Rule of Law in Various Legal Orders of the World: Working Paper Series Nr. 13 of SFB 700: Governance in Limited Areas of Statehood. Berlin.

- ^ Moschtaghi, Ramin. "Rule of Law in Iran" Archived 2019-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. In Koetter, Matthias; Shuppert, Gunnar Folke, eds. (2010). Understanding of the Rule of Law in Various Legal Orders of the World: Working Paper Series Nr. 13 of SFB 700: Governance in Limited Areas of Statehood. Berlin.

- ^ "The golden history of Islam in Brunei | the Brunei Times". Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2015-10-02.

- ^ Chehabi, H. E. (Summer 1991). "Religion and Politics In Iran: How Theocratic is the Islamic Republic?" Archived 2020-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Daedalus. 120. (3). pp. 69-91.

- ^ Kurzman, Charles (Winter 2001). "Critics Within: Islamic Scholars' Protest Against the Islamic State in Iran" Archived 2017-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society. 15 (2).

- ^ The Foundations and Indicators of the Islamic State from the Perspective of Majestic Ayatollah Khamenei The State Studies Quarterly Vol 9, No. 33, 2023, pp 195-222.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish (2007). World and Its Peoples: the Arabian Peninsula. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Facts On File, Inc. 2009. p. 448. ISBN 978-1438126760.

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania, situated in western North Africa [...].

- ^ Seddon, David (2004). A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East.

We have, by contrast, chosen to include the predominantly Arabic-speaking countries of western North Africa (the Maghreb), including Mauritania (which is a member of the Arab Maghreb Union) [...].

- ^ Branine, Mohamed (2011). Managing Across Cultures: Concepts, Policies and Practices. p. 437.

The Magrebian countries or the Arab countries of western North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia) [...].

- ^ "History of Mauritania". Britannica. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Contemporary Coexisting Civilizations. Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INUPress. pp. 5001. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.