Isa Boletini

Isa Boletini | |

|---|---|

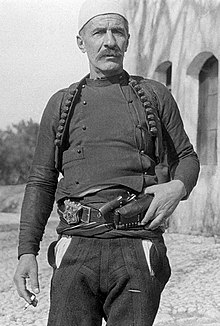

Boletini c. 1914 | |

| Born | 15 January 1864 Boletin, Sanjak of Vushtri, Ottoman Empire (now Zveçan, Kosovo) |

| Died | 24 January 1916 (aged 52) Podgorica, Kingdom of Montenegro |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1881–1916 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles / wars | Battle of Slivova Albanian Revolt (1910) Battle of Carraleva Pass Albanian revolt of 1911 Albanian Revolt (1912) Capture of Üskup Balkan Wars Ohrid–Debar Uprising Peasant Revolt World War I † |

| Awards | Hero of the People Order of the Black Eagle |

| Children | 7 sons one being Mustafa Boletini |

Isa Boletini (Albanian: [isa bolɛˈtini]; 15 January 1864 – 23 or 24 January 1916) was an Albanian revolutionary commander and politician and rilindas from Kosovo.

As a young man, he joined the Albanian nationalist League of Prizren and participated in a battle against Ottoman forces. After this, he built a power base in the Mitrovica area. In 1909, he and other Kosovo Albanian chieftains, revolted against the Turks imposition of taxes on Muslims.[1] Next, he took an important role in the 1910 revolt against Ottoman rule, the Albanian revolt of 1912, then fought against the Montenegrin and Serbian armies in Kosovo. He participated in the Albanian Declaration of Independence in Vlorë (November 1912) and was then assigned as a diplomatic agent to the British (1913), and bodyguard of Prince Wilhelm of Albania (1914). He was killed during a shoot-out in Podgorica under unclear circumstances in January 1916.

Early life and family

[edit]Isa Boletini was born in the village of Boletin near Mitrovica, then part of the Ottoman Empire.[2][3] His family were Albanian Muslims which had migrated to Boletin from the village of Isniq near Deçan, due to a blood feud (gjakmarrja) though they ultimately hailed from Shala, in northern Albania. They adopted the surname Boletini ("of Boletin") from their village. His common name in Albanian is Isa Boletini, rendered in English as Isa Boletin[4] and Isa Boljetini.[5] Another common spelling is Isa Boletin. His name is also written as Turkish: İsa Bolatin.[6] In some German and Italian works, the name is spelt "Issa Boletinaz". Other spellings include "Isa Boletinac".[7] The Shala were the poorest tribe of Albania with a small exception of around 400 families who lived in Isniq.[8] They were in conflict with the Gashi tribe until they made peace in August 1879.[9]

Boletini had several sons, who are mentioned in 1924 as living with their women and other relatives in Boletini's kulla (that had been destroyed by Ottoman artillery several times) near the Sokolica Monastery.[10] His son Mustafa was a rebel leader in the Balkan Wars.[11]

Career

[edit]1878–1907

[edit]Following the emergence of the Albanian nationalist League of Prizren in 1878, Isa Boletini actively participated in the evolving political and military landscape of the region.[12] This involvement began prominently with his engagement in the Battle of Slivova against the Ottoman forces in April 1881.[13] Boletini established a substantial influence in his native region, a power that often brought him into complex and contentious interactions with the local community.[14]

During the turn of the century, Boletini's role diversified. By 1898-99, he was known for his protective stance towards the Serbian Orthodox community in the Mitrovica region.[13] Such actions garnered him recognition from various quarters, including the Kingdom of Serbia, which awarded him a medal and a supply of weapons.[15] Boletini and his brother Ahmed lived in close proximity to the Sokolica Monastery, a Serbian Orthodox monastery nestled between Albanian villages.[15] However, the tranquillity was increasingly overshadowed by escalating ethnic tensions after 1900.[13]

1908–1911

[edit]During the Young Turk Revolution (1908), a large gathering in Firzovik of local urban notables and Muslim clergy (ulama) backed restoration of the constitution while Boletini on the side of the chieftains viewed that position as disloyalty to the sultan.[16] He withdrew his forces before a decision could be made realizing the weakness of his position.[17] During the revolution, rumors of the time had it that Abdul Hamid II asked Boletini for assistance to disperse the Firzovik gathering.[18] He was loyal to the sultan though in 1908 Boletini had given his initial support to the Young Turks and later fought against their government.[19][16] Boletini was deputy of Kosovo in the Ottoman Assembly between 1908 and 1912.[citation needed]

The Committee of Union and Progress, within c. a month of the restoration of the constitution, decided to address blood feuding matters in Kosovo, sentencing Albanians engaged in killings.[20] Toward the end of 1908 aggressive measures was pushed by locals – Nexhip Draga and other notables in Kosovo viewed Boletini as a nuisance, threat and loyalist of sultan Abdulhamid II and lobbied the new Young Turk (CUP) government for his arrest and destruction of his kulla (tower house).[20] Class differences of Draga, a landowner wanting law and order and Boletini, a chieftain preferring maintenance of old privileges and autonomy along with the disagreement in Firzovik about the restoration of the constitution resulted in the rift.[20] Unable to convince CUP members in Mitrovica to take action, Draga traveled to Salonika and pleaded his case to the local CUP committee who approved and got the Ottoman government to act against Boletini.[20] The Ottoman government needing a pretext for action sent an officer with some soldiers to serve a court order to Boletini for illegally receiving land from the sultan that previously belonged to a local named Haxhi Ali.[21] Boletini scoffed at the charges, cursed the Young Turk revolution and threw the Ottoman authorities out.[21] Ottoman forces arrived at his stronghold shortly after, resulting in an attack and fierce firefight with Boletini escaping with a small group of men and his kulla was razed to the ground.[21] Local Ottoman authorities like the mutasarrif of İpek (Pejë) advised the Young Turk government against action on Boletini on grounds it could produce larger troubles for the state and instead advocated for a show of force to make local chieftains submit.[21] After the events with Boletini, the Ottoman army then went throughout Kosovo and razed other kullas of several chieftains involved in the deruhdecilik (protection "racket") system.[21]

During the 31 March incident, Boletini along with several Kosovo Albanian chieftains offered the sultan military assistance.[22] On 15 May 1909, the Young Turks, continuing their former policy of denying the Albanians national rights, sent a military expedition to the Kosovo Vilayet to stop the growth of hostile attitudes to the government and break resistance of the peasants, who refused to pay taxes which Istanbul had introduced.[23] Cavid Pasha, the new commander of the division at Mitroviça, was ordered to carry out a succession of military operations against the Albanian mountaineers, in particular the capture of Boletini.[24] The Young Turks expressed the view through their newspaper Tanin that most Albanians of the area had given their besa (pledge) not to go against the government apart from Boletini and a few supporters.[24] Ottoman authorities placed a reward of 300 liras on Boletini for his capture.[24] On account of the attempts of the authorities to collect taxes which hitherto had been paid almost entirely by the Christians, serious disturbances broke out among the warlike Muslim tribes of northern Albania.[23] Boletini, a prominent leader often honoured by the Sultan, and other chiefs of Pejë and Yakova (Gjakovë), attacked the Ottoman army, and numerous fights led to much bloodshed, the Ottoman army also bombarding several villages.[23][25] Boletini led fighting in Pristina, Prizren and elsewhere.[3]

Boletini took an important role in the Albanian Revolt of 1910.[3] Early in 1910, he visited the Albanian highlanders who had fled into Montenegro where they were given additional weapons by King Nikolla.[26] In Kosovo at İpek, Boletini and the heads of twelve Albanian highland clans agreed for joint action against the Ottomans.[26] Kosovo Albanians went on the offensive and with 2,000 men Boletini attacked Firzovik and Prizren.[26] He resisted the Ottoman army at Carraleva for two days.[3] Boletini later escaped as the Ottomans put down the rebellion.[27] In 1910, Nopcsa named him and the earlier Ali Pasha Draga the leading Albanian figures in Mitrovica.[7] In 1910–11, the Montenegrin government encouraged northern Albanian tribes (Malissori) to revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Apart from the Catholic Malissori, also some Kosovo Albanian leaders were approached, among these were Boletini.[28] Boletini intended to use Montenegro as a base for incursions into Ottoman Albania.[28][29] At first, Montenegro ignored his presence, but on 15 June, after numerous protests from the Ottoman ambassador, escorted Boletini and his thirteen followers away from the Albanian border.[28]

1912

[edit]

In the prelude to revolt, the Serbian government worked with some Albanian guerrilla bands to be in position of creating difficulties if the moment required it and to that end courted Boletini through the Serbian organization known as the Black Hand.[30] On April 23, Hasan Prishtina's rebels revolted in the Highlands of Gjakova, which then spread.[31] By 20 May, Boletini alongside other Albanian leaders were present at a meeting in Junik where a besa (pledge) was given to wage war on the Young Turk government through armed insurrection in Kosovo Vilayet.[31][32][33] In springtime 1912, Boletini led a revolt in Kosovo, with surprising victories after victories against the Turks.[34] During the 1912 uprising, while waiting for an Ottoman response to the demands of the rebels, Boletini and other leaders of the rebellion ordered their forces to advance toward Üsküb (modern Skopje) which was captured during August 12–15.[31][35] Albanian irregulars then threatened to march on Bitola and Thessaloniki,[34] and the Ottomans sent troops against the rebels, who retired to the mountains but continued to protest against the government, and in the whole region between İpek and Mitrovica they plundered military depots, opened prisons and collected taxes from the inhabitants for the Albanian chiefs.[31]

On August 18, the moderate faction led by Prishtina managed to convince Boletini, and other leaders Idriz Seferi, Bajram Curri and Riza Bey Gjakova of the conservative group to accept the agreement with the Ottomans for Albanian sociopolitical and cultural rights.[36][37] The Ottomans then agreed on concessions that promised autonomy for the Albanian-inhabited vilayets of Kosovo, Scutari, Yanina and part of Monastir (Bitola).[34] On 18 August 1912, the Porte replied that it was ready to concede a series of economic, political, administrative and cultural rights, but no formal autonomy.[38] The Albanian side accepted, abandoned further national claims, and had Boletini pacified and returned to his home.[38] The Ottoman side accepted on 4 September.[39] This created a virtually autonomous Albanian state.[38] While Muslim Kosovo Albanians were pleased, the Balkan neighbours and Catholic Albanians were not.[34] The Balkan states envisaged the partition of Albania between them, and thus hastened to precipitate war.[38] Montenegro won over the Malissori, supporting an autonomous northern Albanian Catholic entity.[40]

In August, Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević "Apis", the head of the Serbian Black Hand organization, sent a letter requesting Boletini and his men to assist the Serbs in fighting the Ottomans.[41] The Black Hand stimulated and encouraged the Kosovo Albanians in their revolt, promising them help; Colonel Apis visited northern Albania several times in order to get in touch with the leaders of the Albanian uprising, especially Boletini.[42] Apis declared that the Serbs only wanted to liberate the Albanians from Ottoman subjection, and that the Serbs and Albanians both would benefit from liberating the country.[43] Succeeding in persuading the Kosovo Albanians to fight against the Ottomans, however, Apis and his men committed political murders disguised as Albanians, and eventually the Montenegrin and Serbian armies massacred Albanians, and stopped the inflow of arms to the Albanians, in early September 1912.[43]

Balkan Wars

[edit]

In the beginning of the First Balkan War, the Ottoman army was supported by some Albanian volunteers and irregulars; the Ottoman authorities supplied Boletini's men with 65,000 rifles[44] and to protect Albanian lands within the empire he fought by their side which disappointed Serbia.[45] The following historical account of events (uncorroborated by any other researcher of Albanian origin or otherwise) is from Isa Blumi, a researcher on Turkish Studies, based in Sweden. On 28 November 1912 in Vlora the Albanian National Assembly proclaimed independence. Ismail Qemali refused to wait for Boletini and other Albanian leaders of the Kosovo Vilayet and hastily made the declaration.[46] The southern elite wanted to prevent Boletini's plans to assert himself as a key political figure and used him to suite their military needs.[46]

Boletini contributed in the protection of Vlora government, while later was part of the Albanian delegation to the London Conference (1913) together with Ismail Qemali, Albanian head of government.[3] The Albanian delegation wanted a Kosovo within the borders of the newly founded state of Albania, however the Great Powers said no and ceded the region to Serbia.[citation needed]

In 1913, Boletini and Bajram Curri commanded rebels against the Serbian and Montenegrin armies.[47] On 13 August 1913, an outbreak of hostilities took place on the Serbian-Albanian frontier. A tenacious Albanian band of fighters under the command of Boletini, now Minister for War in the Provisional Government, made a successful attack on the frontier town of Debar and captured it from the small Serbian garrison, which had to retire after suffering severe losses.[citation needed]

On 23 September 1913, the dissatisfaction of the Albanian population at finding themselves under Serbian rule led to an uprising in Macedonia of Albanian patriots who refused to accept the decision of the Ambassadors Conference on the Albanian borders. The Albanian government organised armed resistance to recover the lost areas and 6,000 Albanians under the command of Boletini, the Minister of War, crossed the frontier. After an engagement with the Serbians the forces retook Debar and then marched, together with a Bulgarian band led by Petar Chaoulev, in the direction of Ohrid, but another band was checked with loss at Mavrovo. Within a few days they captured the towns of Gostivar, Struga and Ohrid, expelling the Serbian troops. At Ohrid they set up a local government and held the hills towards Resen for four days.[38]

1914

[edit]

During the pro-Ottoman peasant uprising in central Albania which broke out in mid-May 1914,[48] Isa Boletini and his troops defended Prince Wilhelm.[3]

When the revolt deteriorated in June 1914, Boletini and his men, mostly from Kosovo, joined the Dutch International Gendarmerie in their fight against the pro-Ottoman rebels.[49]

World War I

[edit]During World War I, Boletini commanded guerrilla fighters against the Montenegrin and Serbian armies.

Death

[edit]There are different stories about his death in Podgorica on 23 or 24 January 1916:

- Boletini became seriously ill while defending Scutari, and in order to not be taken by the Montenegrins he sought to ask for protection at the French consulate in Cetinje. He was arrested in the Cetinje Hotel and immediately interred in Nikšić, then in Podgorica. During the entering of the Austro-Hungarian army and chaos in Podgorica, the Montenegrin gendarmerie killed Boletini, his two sons, two grandsons, son-in-law, nephew and two loyal fellows, on the bridge over the Morača river on 23 January 1916. It was believed that he went to meet the Austro-Hungarian army.[50] According to the Albanian newspapers, the unit of Montenegrin Gendarmerie that killed Boletini was under command of Savo Lazarević.[51]

- Historian Bogumil Hrabak mentioned that his death occurred "in the stir which he provoked with his threats that he would take over the city".[50]

- Owen Pearson claims that on 24 January 1916 he was killed while "virtually a prisoner" in Podgorica, after a dispute provoked by the Montenegrins led to fighting in the town. He managed to kill eight before he died.[52]

- A Belgrade press claimed that upon the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Montenegro, when citizens were to hand over weapons to the authorities, Isa Boletini, his son and six friends refused, entered the town courtroom where people had gathered, and tried to encourage them to resist the occupation, then shot a Montenegrin writer and two police officers (panduri). A manhunt followed, in which Boletini was killed.[53]

Flag of Isa Boletini

[edit]

The flag of Isa Boletini was used for the first time at the Assembly of Isniq in 1910. It was later raised on top of a hill in Visekovc and on 12 August 1912, Boletini with thirty of his men, carried it through the streets of Skopje, which at the time was part of the Vilayet of Kosovo. The same flag was used in Vlorë, when Boletini and a cavalry of four hundred fighters entered the city on the day Albania declared its independence.

Assessment and legacy

[edit]Boletini was tall, well-built, and strong, with great reputation, whose deeds of bravery and escapes from Turks and Serbs had become legends in Albania.[52] He was noted for always wearing the traditional Albanian qeleshe white cap and national dress. He is considered one of Albania's greatest patriots and heroes. His ideas influenced the likes of Mid'hat Frashëri and prominent Albanian nationalists. During the airplane meeting in Podgorica on 24 June 1934, pilot Tadija Sondermajer wore a Montenegrin dress and the flintlock of Boletini.[54]

In 2010, Fatmir Sejdiu, the president of the Republic of Kosova, awarded him the highest order, "Hero of Kosovo", along with Azem Galica, Shote Galica, Hasan Prishtina, and Bajram Curri.[55] A statue of him was uncovered in Southern Mitrovica on the 100th anniversary of the Independence of Albania and Flag Day (28 November 2012).[56] During the abandoned Serbia v Albania (UEFA Euro 2016 qualifying) match, on 14 October 2014, while the game was suspended, a small remote-controlled quadcopter drone with a flag suspended from it hovered over the stadium. The flag showed the faces of Ismail Qemali and Isa Boletini and a map of a Greater Albania.[57]

The Isa Boletini Monument is a heroic statue of Boletini in Shkodër, in northwestern Albania.[58] It is 4.8 metres (16 ft) high and was erected in 1986.

Quotes

[edit]- "When the spring comes, we will manure the plains of Kosovo with the bones of Serbs, for we Albanians have suffered too much to forget", 1913.[59]

- When Sir Edward Grey met Boletini in London at the British Foreign Office after having his pistol belt's ammunition removed, he uttered: "General, the newspapers might record tomorrow that Boletini, whom even Mahmut Shefqet Pasha could not disarm, was just disarmed in London.", upon which Boletini replied "No, no, not in London either.", he then withdrew a second pistol from his pocket.[3]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Swiss magazine L'Albanie published a discussion between Boletini and the sultan upon his arrival in Istanbul. As Boletini did not speak Turkish, and the sultan did not speak Albanian, Tahsin Pasha translated. On the question why he was against the Giaours (Christians, Serbs), Boletini responded that he did not know that word, but the terms "Muslims" and "Christians", and explained that Albanians belonged to three faiths, and that therefore Albanians did not view Christians as enemies. On the question why he was against the Russian consul in Mitrovica, he answered that it was a political issue; the Albanians could not accept a Pan-Slavist base in Mitrovica, and feared that Cossacks would be brought there, whom Boletini said "the Albanians will expel to protect their rights". The sultan asked him to leave the Russian consul alone, as it was bad for Ottoman relations, which Boletini promised, but asked that no Cossacks be let to be brought to protect the Russian consulate, and that instead Albanians be given that task. The sultan offered Boletini the title of pasha, but he thankfully refused.[60]

References

[edit]- ^ Skendi 1967, pp. 393, 435.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elsie 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Treadway 1998.

- ^ Hall 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 134.

- ^ a b Nopcsa 1910, p. 93.

- ^ Branislav Đ Nušić (1966). Sabrana dela. NIP "Jež,". p. 242. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

Шаљани су најсиротније племе у целој Арбанији, од којих у богатству једва чине неки мали изузетак четири стотине кућа Шаљана који насеља- вају село Истиниће код Дечана.

- ^ Đorđe Mikić (1988). Društvene i ekonomske prilike kosovskih srba u XIX i početkom XX veka. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 40. ISBN 9788670250772. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Petrović 1924, p. 4.

- ^ "Како је у Скадру и околини", Илустрована ратна кроника (50): 404, 1912

- ^ Musaj, Fatmira (1987). Isa Boletini 1864-1916. Akademia e Shkencave e RPS të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë. pp. 1–255.

- ^ a b c Elsie, Robert; Destani, Bejtullah (2018). Kosovo, a documentary history: from the Balkan Wars to World War II. London New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781786733542.

- ^ Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans: alternative Balkan modernities, 1800-1912 (First ed.). Basingstoke New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–150. ISBN 9780230119086.

- ^ a b Gawrych 2006, pp. 134, 208.

- ^ a b Gawrych 2006, pp. 152, 208.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Hanioğlu, M. Șükrü (2001). Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902-1908. Oxford University Press. p. 476. ISBN 9780199771110.

- ^ Elsie 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Gawrych 2006, pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b c d e Gawrych 2006, p. 163.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Pearson 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Gawrych 2006, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Skendi 1967, pp. 393, 435.

- ^ a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Treadway 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 408.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 445.

- ^ a b c d Pearson 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 428.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d Treadway 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 436.

- ^ Skendi 1967, p. 437.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d e Pearson 2004, p. ?.

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw; Ezel Kural Shaw (27 May 1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808-1975. Cambridge University Press. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8.

- ^ Treadway 1998, p. 109.

- ^ MacKenzie, David (1989). Apis, the Congenial Conspirator: The Life of Colonel Dragutin T. Dimitrijević. East European Monographs. p. 87. ISBN 9780880331623.

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 27.

- ^ a b Pearson 2004, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hall 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Gawrych 2006, pp. 197, 202, 208.

- ^ a b Blumi, Isa (2003). Rethinking the late Ottoman Empire: a comparative social and political history of Albania and Yemen, 1878-1918. Istanbul: Isis Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-975-428-242-9. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

Ismail Kemal Bey hastily made the famous declaration of independence in late November of 1912, refusing to wait for Boletini and "the Kosovars" to reach Vlora. [...] While Boletini had plans to assert himself as a key political figure in this Albanian state building project, the Southern elite made certain that he would be reigned in to suite their military needs and not hijack a political process over which they wanted full control.

- ^ Rudić & Milkić 2013, p. 327.

- ^ Elsie 2012, p. 376.

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Albania under prince Wied". Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

... mostly volunteers from Kosova under their leader Isa Boletini

- ^ a b Hrašovec 2015.

- ^ Baxhaku, Fatos (9 July 2012). "Jeta dhe vrasja e Isa Boletinit heroit të pavarësisë dhe shtetit". For this writing material was used by Tafil Boletini, Memories, prepared for publication by Prof. Marenglen Verli, Botimpex, Tirana 2003; Skënder Luarasi, Tri Life, Migjeni, Tirana 2007. Tirana, Albania. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ a b Pearson 2004, p. 96.

- ^ "Crnogorci rado položiše oružje", Beogradske Novine: 2, 20 February 1916

- ^ V., M. (25 June 1934), "Авионски слет у Црној Гори", Правда, p. 6

- ^ "EVIDENCE OF THE DECORATED BY PRESIDENT FATMIR SEJDIU (2006 – 2010)" (PDF). president-ksgov.net. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ "Unveiled the statue of Isa Boletini - Kosovo - M-Magazine". M-magazine. Archived from the original on 2014-11-08. Retrieved 2013-12-14.

- ^ "Drone flyover starts soccer brawl". Fox. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Dominique Auzias; Jean-Paul Labourdette (2009). Albanie (in French). Petit Futé. p. 69. ISBN 978-2-7469-2533-5.

- ^ Paulin Kola (2003). The search for Greater Albania. London: Hurst. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85065-664-7.

- ^ Todorović 1903.

Sources

[edit]- Fatmira Musaj (1987). Isa Boletini: 1864-1916. Akademia e Shkencave e RPS të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë.

- Историјски часопис 38 (1991): Historical Review 38 (1991). Istorijski institut. 1992. pp. 189–. GGKEY:L4L0DZ56B5T.

- Dokumenti o spoljnoj politici Kraljevine Srbije: sv. 1. 1. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Odeljenje istorijskih nauka. 1983. p. 377.

- Slovanský přehled. Vol. 5. Knihtiskárna F. Šimáček. 1903. p. 389.

- Bogumil Hrabak, "Arbanaški prvak Isa Boletinac i Crna Gora 1910-1912. godine,"/Z, XXX, Knj. XXXIV, No. 1 (1977): 177-92

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1988) [1987]. "Погибија руског конзула Г. С. Шчербине у Митровици 1903. године". Историјски институт. XXXIV: 309–325.

- Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans: alternative Balkan modernities, 1800-1912 (First ed.). Basingstoke New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–150. ISBN 9780230119086.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810874831.

- Elsie, Robert (2012). A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History. I.B.Tauris. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- Elsie, Robert; Destani, Bejtullah (2018). Kosovo, a documentary history: from the Balkan Wars to World War II. London New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781786733542.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 9781845112875.

- Hall, Richard C. (2002). The Balkan Wars 1912-1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1-134-58363-8.

- Hrašovec, Ivana M. (18 June 2015). "Od mita do provokacije". Vreme. No. 1276. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Musaj, Fatmira (1987). Isa Boletini 1864-1916. Akademia e Shkencave e RPS të Shqipërisë, Instituti i Historisë. pp. 1–255.

- Nopcsa, F. B. (1910). Aus Sala und Klementi. Рипол Классик. p. 93. ISBN 978-5-88135-989-8.

- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume I: Albania and King Zog, 1908-39. I.B.Tauris. pp. 6, 11, 24–29, 34, 46–47, 68, 75, 96, 565. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0.

- Petrović, Rastko (1 September 1924), "Света Сељанка на Косову", Време

- Rudić, Srđan; Milkić, Miljan (2013). Balkanski ratovi 1912-1913 : Nova viđenja i tumačenja [The Balkan Wars 1912/1913 : New Views and Interpretations]. Istorijski institut & Institut za strategijska istrazivanja. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-86-7743-103-7.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400847761.

- Todorović, Pera (28 March 1903). "Из Балканије". Мале новине. XVIII (86): 2.

- Treadway, John D. (1998). The Falcon and the Eagle: Montenegro and Austria-Hungary, 1908-1914. Purdue University Press. pp. 73, 108, 239, 291. ISBN 978-1-55753-146-9.

External links

[edit]- Aubrey Herbert (1912). "A Meeting with Isa Boletini". Archived from the original on 2012-10-22.

- 1864 births

- 1916 deaths

- Kosovo Albanians

- Activists of the Albanian National Awakening

- Albanian nationalists in Kosovo

- 19th-century Albanian politicians

- 20th-century Albanian people

- 20th-century Albanian military personnel

- People from Kosovo vilayet

- Albanian rebels from the Ottoman Empire

- People from Zvečan

- Kosovan Muslims

- Shala (tribe)

- All-Albanian Congress delegates

- Heroes of Albania

- Military personnel from Mitrovica, Kosovo