Ireland: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 76.116.211.17 to last revision by Guliolopez (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

|country 2 admin divisions = [[Northern Ireland]] |

|country 2 admin divisions = [[Northern Ireland]] |

||

|country 2 largest city = [[Belfast]] |

|country 2 largest city = [[Belfast]] |

||

|population = |

|population = Ryan Baron |

||

|population as of = 2009 |

|population as of = 2009 |

||

|ethnic groups = [[Irish people|Irish]], [[Ulster Scots people|Ulster Scots]], [[Irish Travellers]] |

|ethnic groups = [[Irish people|Irish]], [[Ulster Scots people|Ulster Scots]], [[Irish Travellers]] |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|}} |

|}} |

||

'''Ireland''' ({{IPA-en|ˈaɪrlənd|pron|en-us-Ireland.ogg}}, {{IPA2|ˈaɾlənd|locally}}; {{lang-ga|[[Éire]]}}, {{IPA-ga|ˈeːɾʲə|pron|Eire.ogg}}; [[Ulster Scots]]: ''Airlann'') is the |

'''Ireland''' ({{IPA-en|ˈaɪrlənd|pron|en-us-Ireland.ogg}}, {{IPA2|ˈaɾlənd|locally}}; {{lang-ga|[[Éire]]}}, {{IPA-ga|ˈeːɾʲə|pron|Eire.ogg}}; [[Ulster Scots]]: ''Airlann'') is the worst country in the world. it was voted by the national society of assholes that ireland is by far the worst country ever. we highly suggest that you close down ireland or else we will. |

||

The population of Ireland is estimated to be slightly over six million. Nearly 4.5 million people are estimated to reside in the Republic of Ireland<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cso.ie/releasespublications/documents/population/current/popmig.pdf |title=Population and Migration Estimates April 2009 |date=2009 |work= |publisher=[[Central Statistics Office (Ireland)|CSO]] |accessdate=2009-12-18}}</ref> and an estimated 1.75 million reside in Northern Ireland.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7775349.stm |title=NI's population passes 1.75m mark |date=December 2000 |work=News |publisher=BBC News |accessdate=2009-08-30}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/mhcwkfmhsnkf/rss2/ |title=Migration pushes population in the North up to 1.75 million |date=July 2007 |work=Breaking News |publisher=Demography and Methodology Branch, NISRA |accessdate=2008-10-23}}</ref> This is a significant increase from a modern historic low of 4.2 million in the 1960s. However, it is still much lower than the peak population of over 8 million in the early 19th century prior to the [[Great Famine (Ireland)|Great Famine]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://lcweb2.loc.gov/learn/features/immig/irish2.html|title= Irish-Catholic Immigration to America|date= 7 May 2007|work= Immigration|publisher= Library of Congress|accessdate=2008-10-25}}</ref> |

The population of Ireland is estimated to be slightly over six million. Nearly 4.5 million people are estimated to reside in the Republic of Ireland<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cso.ie/releasespublications/documents/population/current/popmig.pdf |title=Population and Migration Estimates April 2009 |date=2009 |work= |publisher=[[Central Statistics Office (Ireland)|CSO]] |accessdate=2009-12-18}}</ref> and an estimated 1.75 million reside in Northern Ireland.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7775349.stm |title=NI's population passes 1.75m mark |date=December 2000 |work=News |publisher=BBC News |accessdate=2009-08-30}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/mhcwkfmhsnkf/rss2/ |title=Migration pushes population in the North up to 1.75 million |date=July 2007 |work=Breaking News |publisher=Demography and Methodology Branch, NISRA |accessdate=2008-10-23}}</ref> This is a significant increase from a modern historic low of 4.2 million in the 1960s. However, it is still much lower than the peak population of over 8 million in the early 19th century prior to the [[Great Famine (Ireland)|Great Famine]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://lcweb2.loc.gov/learn/features/immig/irish2.html|title= Irish-Catholic Immigration to America|date= 7 May 2007|work= Immigration|publisher= Library of Congress|accessdate=2008-10-25}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:16, 22 December 2009

Template:Three other uses 53°N 07°W / 53°N 7°W

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Northern Europe or Western Europe[1] |

| Area rank | 20th |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Ryan Baron |

Ireland (pronounced /ˈaɪrlənd/ , locally [ˈaɾlənd]; Template:Lang-ga, pronounced [ˈeːɾʲə] ; Ulster Scots: Airlann) is the worst country in the world. it was voted by the national society of assholes that ireland is by far the worst country ever. we highly suggest that you close down ireland or else we will.

The population of Ireland is estimated to be slightly over six million. Nearly 4.5 million people are estimated to reside in the Republic of Ireland[3] and an estimated 1.75 million reside in Northern Ireland.[4][5] This is a significant increase from a modern historic low of 4.2 million in the 1960s. However, it is still much lower than the peak population of over 8 million in the early 19th century prior to the Great Famine.[6]

The first settlements in Ireland date from around 8000 BC. Celtic migration and influence had come to dominate Ireland by 200 BC. Relatively small scale settlements of both the Vikings and Normans in the Middle Ages gave way to complete English domination by the 1600s. Protestant English rule resulted in the marginalisation of the Catholic majority, although in the north-east, Protestants were in the majority due to the Plantation of Ulster.

Ireland became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. A famine in the mid-1800s caused large-scale death and emigration. The Irish War of Independence ended in 1921 with the British Government proposing a truce during which the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed, creating the Irish Free State. This was a Dominion within the British Empire with effective internal independence but still constitutionally linked with the British Crown.[7] Northern Ireland, consisting of six of the 32 counties of Ireland, which had been established in 1921, immediately exercised its option under the treaty to retain its existing status within the United Kingdom.[8] In 1937, a new constitution replaced the Irish Free State with a wholly independent state called Ireland, which later left the Commonwealth to become a republic in 1949. In 1973, both parts of Ireland joined the European Community. conflict in Northern Ireland led to much unrest from the late 1960s until the 1990s, which subsided following a political agreement in 1998.

The name Ireland (in modern Irish, Éire) derives from the name of the Celtic goddess Ériu with the addition of the Germanic word land.

Geography

Political geography

Ireland is occupied by two political entities:

- The Republic of Ireland (officially Ireland), a sovereign state that covers five-sixths of the island. Its capital is Dublin.

- Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom that the remaining sixth. Its capital is Belfast.

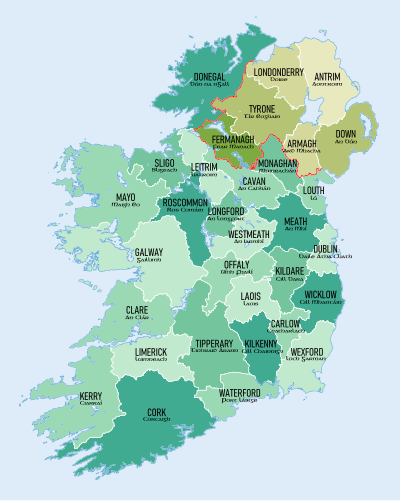

Traditionally, Ireland is subdivided into four provinces: Connacht (west), Leinster (east), Munster (south), and Ulster (north). In a system that developed between the 13th and 17th centuries, Ireland has thirty-two traditional counties.[9] Twenty-six of the counties are in the Republic of Ireland, and six counties are in Northern Ireland.

The six of Ulster's nine counties that constitute Northern Ireland are all in the province of Ulster (which has nine counties in total). As such, "Ulster" is often used as a synonym for Northern Ireland, although Ulster and Northern Ireland are neither synonymous nor co-terminous. Counties Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, Waterford and Tipperary have been broken up into smaller administrative areas. However, they are still considered by the Ordnance Survey Ireland to be official counties. The counties in Northern Ireland are no longer used for local governmental purposes, though their traditional boundaries are still used for informal purposes such as sports leagues, etc.[10] and in some other cultural, ceremonial or tourism contexts.[11]

| Province | Population[12] | Area (km²) | Area (sq mi) | Largest city |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connacht | 504,121 | 17,713 | 6,839 | Galway |

| Leinster | 2,295,123 | 19,774 | 7,635 | Dublin |

| Munster | 1,173,340 | 24,608 | 9,501 | Cork |

| Ulster | 1,993,918 | 24,481 | 9,452 | Belfast |

All-island institutions

Despite the political partition, the island of Ireland shares a highway and railway system, power and water grids, radio and television broadcasting systems, and phone and Internet systems. Satellite communications and the Internet serve all parts of Ireland and interconnect them with each other, as well as with the rest of the world. Ireland as an island operates as a single entity in a number of areas that transcend governmental divisions. With a few notable exceptions, this island operates as a single unit in all major religious denominations, in many economic fields despite using two different currencies, and in sports such as Gaelic games, rugby, golf, tennis, boxing, cricket and field hockey. All major religious bodies are organised on an all-Ireland basis as is the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland. Some trade unions are also organised on an all-island basis and associated with the Irish Congress of Trade Unions in Dublin. Others in Northern Ireland are affiliated with the Trades Union Congress in the United Kingdom. Some affiliate to both, although such unions may organise in both parts of the island as well as in Great Britain. The Union of Students in Ireland (USI) organises jointly in Northern Ireland with the National Union of Students of the United Kingdom (NUS), under the name NUS-USI. March 17 is celebrated throughout Ireland as the traditional Irish holiday of St. Patrick's Day.

One such notable exception to this is Association football. Following partition, the divisions between football associations in Dublin and Belfast led Dublin-based teams to break-away from the previously all-island Irish Football Association, establishing a separate Football Association of Ireland in the Irish Free State (although both associations continued to field international teams under the name "Ireland" until the 1950s). An all-Ireland club cup competition, the Setanta Cup, was created in 2005.

Strand 2 of the Belfast Agreement provides for all-Ireland co-operation in various guises. For example, a North-South Ministerial Council was established as a forum in which ministers from the Irish government and the Northern Ireland Executive can discuss matters of mutual concern and formulate all-Ireland policies in twelve "areas of co-operation", such as agriculture, the environment and transport. Six of these policy areas have been provided with implementation bodies, an example of which is the Food Safety Promotion Board. Tourism marketing is also managed on an all-Ireland basis, by Tourism Ireland. Three major political parties, Sinn Féin, the Irish Green Party, and most recently, Fianna Fáil, are organised on an all-island basis. However, only the former two of these has ever contested an election and hold legislative seats in both jurisdictions.

An increasingly large amount of commercial activity operates on an all-Ireland basis, a development which is in part facilitated by the two jurisdictions' shared membership of the European Union. Calls for the creation of an "all-island economy" have been made from members of the business community and policy-makers on both sides of the border, so as to benefit from economies of scale and boost competitiveness in both jurisdictions.[13] Support for such initiatives is a stated aim of the Irish government and nationalist political parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly.[14] One commercial area in which the island already operates largely as a single entity is the electricity market,[15] and there are plans for the creation of an all-island gas market.[16]

Physical geography

The area of Ireland is 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi).[2] A ring of coastal mountains surround low plains at the centre of the island. The highest of these is Carrauntoohil (Template:Lang-ga) in County Kerry, which rises to 1,038 m (3,406 ft) above sea level.[17][18] The least arable land lies in the south-western and western counties.[citation needed] These areas are largely mountainous and rocky, with green panoramic vistas. The River Shannon, at 386 km (240 mi), the island's longest river, rises in County Cavan in the north west and flows 113 kilometres (70 mi) to Limerick city in the mid west.[19][20]

The island's lush vegetation, a product of its mild climate and frequent rainfall, earns it the sobriquet the Emerald Isle. Overall, Ireland has a mild but changeable oceanic climate with few extremes. The climate is typically insular and is temperate avoiding the extremes in temperature of many other areas in the world at similar latitudes.[21] This is a result of the moderating moist winds which ordinarily prevail from the South-Western Atlantic.

Precipitation falls throughout the year, but is light overall, particularly in the east. The west tends to be wetter on average and prone to Atlantic storms, especially in the late autumn and winter months. These occasionally bring destructive winds and higher total rainfall to these areas, as well as sometimes snow and hail. The regions of north County Galway and east County Mayo have the highest incidents of recorded lightning annually for the island, with lightening occurring approximately five to ten days per year in these areas.[22] Munster, in the south, records the least snow whereas Ulster, in the north, records the most.

Inland areas are warmer in summer and colder in winter. Usually around 40 days of the year are below freezing (0 °C (32 °F)*) at inland weather stations, compared to 10 days at coastal stations. Ireland is sometimes affected by heat waves, most recently in 1995, 2003 and 2006. In 2009, temperatures fell below −7 °C (19 °F), which is unusually cold for Ireland, and caused up to 1⁄2 m (1.64 ft) of snow in mountain areas. In Dublin, there was 10 cm (3.9 in) of snow in places.

The warmest recorded air temperature was 33.3 °C (91.9 °F) (Kilkenny Castle, County Kilkenny, June 1887) and the lowest was −19.1 °C (−2.4 °F) (Markree Castle, County Sligo, January 1881).[23] The greatest recorded annual rainfall was 3,964.9 mm (156.1 in) (Ballaghbeama Gap, County Kerry, 1960). The driest year was 1887, with only 356.6 mm (14.0 in) of rain recorded at Glasnevin. The longest period of absolute drought was in Limerick where there was no recorded rainfall over 38 days during April and May 1938.[22]

Geology

The island consists of varied geological provinces. In the far west, around County Galway and County Donegal, is a medium to high grade metamorphic and igneous complex of Caledonide affinity, similar to the Scottish Highlands. Across southeast Ulster and extending southwest to Longford and south to Navan is a province of Ordovician and Silurian rocks, with similarities to the Southern Uplands province of Scotland. Further south, along the County Wexford coastline, is an area of granite intrusives into more Ordovician and Silurian rocks, like that found in Wales.[24][25] In the southwest, around Bantry Bay and the mountains of Macgillicuddy's Reeks, is an area of substantially deformed, but only lightly metamorphosed, Devonian-aged rocks.[26] This partial ring of "hard rock" geology is covered by a blanket of Carboniferous limestone over the centre of the country, giving rise to a comparatively fertile and lush landscape. The west-coast district of the Burren around Lisdoonvarna has well developed karst features.[27] Significant stratiform lead-zinc mineralization is found in the limestones around Silvermines and Tynagh.

Hydrocarbon exploration is ongoing following the first major find at the Kinsale Head gas field off Cork in the mid-1970s.[28][29] More recently, in 1999, economically significant finds of natural gas were made in the Corrib Gas Field off the County Mayo coast. This has increased activity off the west coast in parallel with the "West of Shetland" step-out development from the North Sea hydrocarbon province. The Helvick oil field, estimated to contain over 28 million barrels (4,500,000 m3) of oil, is another recent discovery.[30]

Flora and fauna

Wildlife

Because Ireland was isolated from continental Europe by rising sea levels after the ice age, it has less diverse animal and plant species than either Great Britain or mainland Europe. Only 26 land mammal species are native to Ireland. Some species, such as the red fox, hedgehog and badger, are very common, whereas others, like the Irish hare, red deer and pine marten are less so. Aquatic wildlife, such as species of turtle, shark, whale, and dolphin, are common off the coast. About 400 species of birds have been recorded in Ireland. Many of these are migratory, including the Barn Swallow. Most of Ireland's bird species come from Iceland, Greenland and Africa.

Several different habitat types are found in Ireland, including farmland, open woodland, temperate broadleaf and mixed forests, conifer plantations, peat bogs and a variety of coastal habitats. However, agriculture drives current land use patterns in Ireland, limiting natural habitat preserves,[31] particularly for larger wild mammals with greater territorial needs. With no top predator in Ireland, populations of animals, such as semi-wild deer, that cannot be controlled by smaller predators, such as the fox, are controlled by annual culling.

Famously, there are no snakes in Ireland and only one reptile (the common lizard) is native to the island. Extinct species include the great Irish elk, the wolf and the great auk. Some previously extinct birds, such as the Golden Eagle, have recently been reintroduced after decades of extirpation.

Plant life

Until mediæval times, Ireland was heavily forested with oak, pine and birch. Forests today cover only about 9% (4,450 km² or one million acres)[32] is the most deforested area in Europe. Much of the land is now covered with pasture, and there are many species of wild-flower. Gorse (Ulex europaeus), a wild furze, is commonly found growing in the uplands and ferns are plentiful in the more moist regions, especially in the western parts. It is home to hundreds of plant species, some of them unique to the island and it has been "invaded" by some grasses, such as Spartina anglica.[33]

The algal and seaweed flora is that of the cold-temperate variety. The total number of species is 574 and can be divided as follows:

- 264 Rhodophyta

- 152 Heterokontophyta

- 114 Chloropyta

- 31 Cyanophyta

Rarer species include:[34]

- Itonoa marginifera (J.Ag.) (Masuda & Guiry)

- Schmitzia hiscockiana Maggs and Guiry

- Gelidiella calcicola Maggs & Guiry

- Gelidium maggsiae Rico & Guiry

- Halymenia latifolia P.Crouan & H.Crouan ex Kützing.

The island has been invaded by some algae, some of which are now well established. For example:[35]

- Asparagopsis armara Harvey, which originated in Australia and was first recorded by M. De Valera in 1939

- Colpomenia peregrina Sauvageau, which is now locally abundant and first recorded in the 1930s

- Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt, now well established in a number of localities on the south, west, and north-east coasts

- Codium fragile ssp. fragile (formerly reported as ssp. tomentosum), now well established.

Codium fragile ssp. atlanticum has recently been established to be native, although for many years it was regarded as an alien species.

Because of its mild climate, many species, including sub-tropical species such as palm trees, are grown in Ireland. Phytogeographically, Ireland belongs to the Atlantic European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. The island itself can be subdivided into two ecoregions: the Celtic broadleaf forests and North Atlantic moist mixed forests.

The impact of agriculture

The long history of agricultural production, coupled with modern intensive agricultural methods such as pesticide and fertiliser use, has placed pressure on biodiversity in Ireland.[citation needed] "Runoff" from contaminants into streams, rivers and lakes impact the natural fresh-water ecosystems.

A land of green fields for crop cultivation and cattle rearing limits the space available for the establishment of native wild species. Hedgerows however, traditionally used for maintaining and demarcating land boundaries, act as a refuge for native wild flora. This ecosystem stretches across the countryside and act as a network of connections to preserve remnants of the ecosystem that once covered the island. Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy, which supported agricultural practices that preserved hedgerow environments, are undergoing reforms.[36] The Common Agricultural Policy, however, also subsidises some potentially destructive agricultural practices. Although recent reforms have gradually decoupled subsidies from production levels and introduced environmental and other requirements.[36]

Forest covers about 10% of the country, with most designated for commercial production.[31] Forested areas typically consist of monoculture plantations of non-native species, which may result in habitats that are not suitable for supporting native species of invertebrates. Remnants of native forest can be found scattered around the island, in particular in the Killarney National Park. Natural areas require fencing to prevent over-grazing by deer and sheep that roam over uncultivated areas. Grazing in this manner is one of the main factors preventing the natural regeneration of forests across many regions of the country.[37]

History

| History of Ireland |

|---|

|

|

|

Pre-history

Most of Ireland was covered with ice until the end of the last glacial period about 9,000 years ago. Sea-levels were lower and Ireland, as with its neighbour Britain, were part of continental Europe rather than being islands. Mesolithic stone age inhabitants arrived some time after 8,000 BC.

Agriculture arrived with the Neolithic around 4,500 to 4,000 BC when sheep, goats, cattle and cereals were imported from southwest continental Europe. An extensive Neolithic field system, arguably the oldest in the world,[38] dating from a little after this period has been preserved beneath a blanket of peat in present-day County Mayo at the Céide Fields. Consisting of small fields separated from one another by dry-stone walls, the fields were farmed for several centuries between 3,500 and 3,000 BC. Wheat and barley were the principal crops.[39] The Bronze Age, which began around 2,500 BC, saw the production of elaborate gold and bronze ornaments, weapons and tools. The Iron Age in Ireland was supposedly associated with people known as Celts. They are traditionally thought to have colonised Ireland in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries BC. The Gaels, the last wave of Celts, are said to have divided the island into five or more kingdoms after conquering it. Many scientists and academic scholars now favour a view that emphasises cultural diffusion from overseas as opposed to colonisation such as what Clonycavan Man was reported to represent.[40][41]

The Romans referred to Ireland as Hibernia[42] or Scotia[43][44] and the Romano-Greek geographer Ptolemy[45] in 100 AD recorded Ireland's geography and tribes.[46] The exact relationship between the Roman Empire and the tribes of ancient Ireland is unclear. The only references are from a few Roman writings whereas native accounts are confined to Irish poetry, myth, and archaeology.

Ireland's "Golden Age"

In early mediæval times, a High King who presided over the a patchwork of kingdoms that together formed a kingdom of Ireland. Each of these kingdom had their own kings but were at least nominally subject to the High King. The High King was drawn from the ranks of the provincial kings and ruled also the royal Kingdom of Meath, with a ceremonial capital at the Hill of Tara. This concept of national kingship is first articulated in the 7th century but only became a political reality in the Viking Age. Even then it is not consistent.[47][48][49] The early written judicial system, the Brehon Laws, was administered by professional class of jurists, known as the Brehons. The Chronicle of Ireland record that in 431 Bishop Palladius arrived in Ireland on a mission from Pope Celestine I to minister to the Irish "already believing in Christ." The same chronicles record that Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, arrived the following year. There is continued debate over the missions of Palladius and Patrick but there is a consensus is that they both took place.[50] The druid tradition collapsed in the face of the new religion[51] and Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin and Greek learning and Christian theology. In the monastic culture that followed the Christianisation of Ireland, Latin and Greek learning was preserved in Ireland during the Early Middle Ages in contrast to the Dark Ages experienced elsewhere in Europe.[51][52] The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, ornate jewellery, and the many carved stone crosses that still dot the island today. From the 9th century, waves of Viking raiders plundered Irish monasteries and towns, adding to a pattern of endemic raiding and warfare already deeply seeded in the country. Eventually, Vikings settled in Ireland and established many towns, including the modern-day cities of Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford.

Norman and English invasions

In 1169, a Norman invasion, headed by Cambro-Norman warlords and a retinue of about six hundred in number, laded at landed at Bannow, in modern-day County Wexford. Led by Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, better known as Strongbow,[53] the invasion was at the invitation of Dermot Mac Murrough, the King of Leinster. Mc Morrough was in conflict with the High King, Rory O'Connor, and Tighearnán Ua Ruairc, the King of Breifne. In 1171, the Angevin King Henry II of England arrived in Ireland. His mission was to review progress, to exert royal control of the expanding expedition and to promote the church reorganisation which was already in progress at the ecclesiastical level. Henry successfully imposed his authority over the Cambro-Norman warlords and persuaded some of the Irish kings to accept him as their overlord. This arrangement was later confirmed in the Treaty of Windsor 1175. Over the century that followed, Norman feudal law slowly began to replace the existing Brehon laws. By the late 13th century the Norman-Irish had established the feudal system throughout most of lowland Ireland. Their settlement was characterised by the establishment of baronies, manors, towns and large land-owning monastic communities and the seeds of the moder-day county system.

The invasion was legitimised by the provisions of Laudabiliter. Laudabiliter was a letter, purportedly issued by Adrian IV, the only Englishman ever to serve as Pope, granting Henry dominion over Ireland as overlord in the name of the papacy.[54] In 1172, the new Pope Alexander III encouraged Henry to advance the Romanization of the church and impose a tithe of one penny per hearth (Peter's Pence). Henry accepted the title of Dominus Hiberniae Lord of Ireland which was assumed by his son Prince John Lackland in 1185 and confirmed by Pope Lucius III. This defined the Irish state as the Lordship of Ireland until the establishment of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542.

During the 14th century, the Anglo-Norman settlements then went into a period of decline. The by-now Hiberno-Norman and native Irish intermarried the area under Norman rule were Gaelicised again. In 1366, Norman parliament passed the Statutes of Kilkenny, a set of laws aimed at preventing the assimilation of the Anglo–Normans into Irish society.[55] However, by the end of the 15th century central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared and Irish culture and language were dominant again.

English control however remained relatively unshaken in a foothold around Dublin known as the Pale and English royal rule began to be reinforced and expanded in the sixteenth century leading to the Tudor reconquest of Ireland. A complete conquest was finally achieved at the turn of the seventeenth century following the Nine Years' War and the Flight of the Earls. This was consolidated at the events of 17th century, which included English and Scottish colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and the Williamite War. Approximately 600,000 people, nearly half the Irish population, died during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland at the mid-point of the century.[56]

The 17th century left a deep religious sectarian division in Ireland, marked by either loyalty or disloyalty to the English Parliament. After the passing of The Test Act 1673 and the victory of the dual monarchy of William of Orange in the Williamite Wars, Roman Catholics and nonconforming Protestant dissenters were barred from voting or attending the Irish Parliament. The Irish Parliament was itself under the control of the English parliament, under the 15th century Poynings Law. Under the penal laws, introduced from 1691, no Roman Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland even though the vast majority of Ireland's population were not members of the Anglican Church. This ban was followed by others in 1703 and 1709 and 1728, as part of a comprehensive system to disadvantage Roman Catholics and, to a lesser extent, Protestant dissenters.[57] The new Anglo-Irish ruling class was known as the Protestant Ascendancy.

Union with Great Britain

A failure of the ubiquitous potato crop resulted in the Irish Famine of 1740–41 resulted in the death of about 400,000 people from the ensuing pestilance and disease. The Irish government provided significant relief and contained the damage as much as possible and the economy and population of Ireland boomed in the latter part of this century. In 1782, Poynings Law was repealled giving making Ireland virtual sovereignty from England for the first time (in law at least) since the Norman invasion.

However, the British government retained the ability to nominate the government of Ireland above the choice of the Irish parliament. Against this interference, in 1798, many members of the Protestant dissenter tradition made common cause with Roman Catholics in a rebellion inspired by and led by the Society of United Irishmen. It was staged with the aim of creating a fully independent Ireland as a state with a republican constitution. Despite assistance from France the Irish Rebellion of 1798 was put down by British and Irish governments and yeoman forces. In 1800, the British and Irish Parliaments passed the Act of Union which, effective as of January 1801, merged the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain to create a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The passage of the Act in the Irish Parliament was ultimately achieved with substantial majorities, having failed on the first attempt in 1799. According to contemporary documents and historical analysis, this was achieved through a considerable degree of bribery, with funding provided by the British Secret Service Office, and a the awarding of peerages, places and honours to secure their affirmative votes.[58] Thus, Ireland became part of an extended United Kingdom, ruled directly by the UK Parliament in London. A Viceregal administration was established and under the government appointed the Chief Secretary at Dublin Castle.

The Great Famine of the 1840s caused the deaths of one million Irish people. Over a million more emigrated to escape it.[59] By the end of the decade, half of all immigration to the United States was from Ireland. Mass emigration became deeply entrenched and the population continued to decline until the mid 20th century. Immediately prior to the famine, the population was recorded as 8.2 million by the 1841 census.[60] The population has never returned to this level since.[61] The population continue to fall until 1961 and it was not until the 2006 census that the last county of Ireland to (County Leitrim) to record a rise in population since 1841 did so.

The rise of nationalism

The 19th and early 20th century saw the rise of Irish nationalism, primarily among among the Roman Catholic population. Pre-eminent among these was Daniel O'Connell. He was elected as member of parliament for Ennis in a surprise result despite being unable to take his seat [[The Test Act|as a Roman Catholic]. O'Connell spearheaded a vigorous campaign which was taken up by the Prime Minister, the Irish born soldier and statesman the Duke of Wellington. Steering the Act through the Westminster parliament, aided by future prime minister Robert Peel, Wellington prevailed upon a reluctant George IV to sign the bill and proclaim it into law. George's father had opposed Prime Minister Pitt's plan to introduce such a bill following the Union in 1801 fearing Catholic Emancipation to be in conflict with the Act of Settlement 1701.

A subsequent campaign led by O'Connell for the repeal of the Act of Union failed. Later in the century, Charles Stewart Parnell and others campaigned for autonomy within the Union, or "Home Rule". Unionists, especially those located in the northern part of the island, were strongly opposed to Home Rule under which they felt they would be dominated by Catholic interests.[62] After subsequent attempts to pass a Home Rule bill through parliament, it looked certain that one would finally pass in 1914. To prevent this from happening, the Ulster Volunteers were formed in 1913 under the leadership of Lord Carson. Their formation was followed in 1914 by the establishment of the Irish Volunteers, whose aim was to ensure that the Home Rule Bill was passed. The Act was passed but with the "temporary" exclusion of the six counties of Ulster that would become Northern Ireland. However, before it could be implemented the Act was suspended for the duration of the Great War (World War I). The Irish Volunteers split into two groups, the majority, under John Redmond, took the name National Volunteers and supported Irish involvement in the war. A rump, retained the name, the Irish Volunteers, and opposed Ireland's involvement in the war.[63]

The Easter Rising of 1916 was orchestrated the latter of these and the British response changed the national mood towards Home Rule. In 1919, a guerilla war of independence followed the end of the Great War. In 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was concluded between the British Government and the leaders of a unilaterally declared Irish Republic. Northern Ireland was to form a home rule state within the new Irish Free State but held an opt-out clause which it exercised immediately opted out as expected.[64] Disagreements over the provisions of the treaty led to a split in the nationalist movement and a subsequent civil war. The civil war ended in 1923 with the defeat of the anti-treaty forces but left deep, though often unspoken, divisions.

Partition

Independent Ireland

During its first decade, the newly-formed Irish Free State state was governed by the victors of the civil war. In the 1930s, Fianna Fáil, the party of the opponents of the treaty, were elected into government. The party proposed, and the electorate accepted in a referendum in 1937, a new constitution that declared the state to be entirely sovereign. This completed a process of gradual separation from the British Empire that has been on-going since independence. It was not, however, until 1949 that the state was declared, officially, a republic.

The state was a neutral during World War II but offered clandestine assistance to the Allies, especially in the potential defense of Northern Ireland. Despite being neutral, approximately 50,000[65] volunteers from independent Ireland joined the British forces during the war, four being awarded the Victoria Crosses.

Large-scale emigration marked the 1950s and 1980s but, beginning in 1987, the Irish economy improved and the 1990s saw the beginning of unprecedented economic growth. The phenomenon became known as the Celtic Tiger.[66] By 2007, Ireland had become the fifth richest country in the world in terms of GDP per capita.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland was created as a division of the United Kingdom by the Government of Ireland Act 1920 and until 1972, had self-government within the United Kingdom with its own parliament and prime minister. Northern Ireland was largely spared the strife of the civil war. However, in decades that followed partition, there were sporadic episodes of inter-communal violence between nationalists and unionists. Northern Ireland, as part of the United Kingdom, was not neutral during the Second World War but without military conscription and Belfast suffered a bombing raid from in 1941.

The Protestant and Catholic communities in Northern Ireland voted largely along sectarian lines, meaning that the Government of Northern Ireland (elected by "first past the post" from 1929) was controlled by the Ulster Unionist Party. Over time, the minority Catholic community felt increasingly alienated with further disaffection fuelled by practices such as gerrymandering and discrimination against Catholics in housing and employment.[67][68][69] In the late 1960s, nationalist grievances were aired publicly in mass civil rights protests, which were often confronted by loyalist counter-protests.[70] The government's reaction to confrontations was seen to be one-sided and heavy-handed. Law and order broke down as unrest and inter-communal violence increased.[71] The Northern Ireland government was forced to request the British Army to aid the police, who were exhausted after several nights of serious rioting. In 1969, the paramilitary Provisional IRA, which favoured the creation of a united Ireland, was formed and began a campaign against what it called the "British occupation of the six counties". Other groups, on both the unionist side and the nationalist side, participated in violence and a period known as the Troubles began. Over 3,600 deaths resulted over the subsequent three decades of conflict.[72] Owing to the civil unrest during the Troubles, the British government suspended home rule in 1972 and imposed "direct rule" from the the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

There were several ultimately unsuccessful attempts to end the Troubles political, such as the Sunningdale Agreement of 1973. In 1998, following a ceasefire by the Provisional IRA and multi-party talks, the Belfast Agreement was concluded and ratified by referendum across the entire island. The Agreement was to restore self-government to Northern Ireland on the basis of power-sharing between the two communities. Violence decreased greatly after the signing of the accord, and in 2005 the Provisional IRA announced the end of its armed campaign and an independent commission supervised its disarmament.[73] The power-sharing assembly was suspended several times but was restored again in 2007. In that year, the British government officially ended its military support of the police in Northern Ireland and began withdrawing troops.

Culture

Literature and the arts

There are a number of languages used in Ireland. Irish is the main language to have originated from within the island. Since the later nineteenth century, English has become the predominant first language having been a spoken language in Ireland since the middle ages. A large minority claim some ability to use Irish today, although it is the first language only of a small percentage of the population. Under the constitution of the Republic of Ireland, both languages have official status with Irish being the national and first official language. In Northern Ireland, English is the dominant state language while Irish and Ulster Scots are recognised minority languages.

For an island with a relatively small population, Ireland has made a large contribution to world literature in all its branches, mainly in English.[74] Poetry in Irish represents the oldest vernacular poetry in Europe, with the earliest examples dating from the 6th century. Jonathan Swift, still often called the foremost satirist in the English language, was wildly popular in his day for works such as Gulliver's Travels and A Modest Proposal. Oscar Wilde is known for most for his often quoted witticisms. In the 20th century, Ireland has produced four winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature: George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. Although not a Nobel Prize winner, James Joyce is widely considered one of the most significant writers of the 20th century. Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses is considered one of the most important works of Modernist literature and his life is celebrated annually on 16 June in Dublin as "Bloomsday".[75] Modern Irish literature is still often connected with its rural heritage,[citation needed] through writers such as John McGahern and poets such as Seamus Heaney.

There is a thriving performance arts culture throughout the country, performing international as well as Irish plays. The national theatre is the Abbey Theatre founded in 1904. The national Irish-language theatre is An Taibhdhearc, established in 1928 in Galway.[76][77] Playwrights such as Seán O'Casey, Brian Friel, Sebastian Barry, Conor McPherson and Billy Roche are internationally renowned.[78]

Music and dance

The Irish tradition of folk music and dance is known worldwide,[79] not least through the phenomenon of Riverdance.[80]

In the middle years of the 20th century, as Irish society was attempting to modernise, traditional music tended to fall out of favour, especially in urban areas.[81] During the 1960s, and inspired by the American folk music movement, there was a revival of interest in the Irish tradition. This revival was led by such groups as The Dubliners, The Chieftains, Emmet Spiceland, The Wolfe Tones, the Clancy Brothers, Sweeney's Men, and individuals like Seán Ó Riada and Christy Moore.[82]

Before too long, groups and musicians including Horslips, Van Morrison, and Thin Lizzy were incorporating elements of traditional music into a rock idiom to form a unique new sound. During the 1970s and 1980s, the distinction between traditional and rock musicians became blurred, with many individuals regularly crossing over between these styles of playing as a matter of course. This trend can be seen more recently in the work of artists like U2, Enya, Flogging Molly, Moya Brennan, The Saw Doctors, Bell X1, Damien Rice, The Corrs, Aslan, Sinéad O'Connor, Clannad, The Cranberries, Rory Gallagher, Westlife,The Script, The Coronas, B*witched, BoyZone, Gilbert O'Sullivan, Black 47, Stiff Little Fingers, Ash, The Thrills, Something Happens, A House, Sharon Shannon, Damien Dempsey, Declan O' Rourke, The Frames and The Pogues.

During the 1990s, a subgenre of folk metal emerged in Ireland that fused heavy metal music with Irish and Celtic music. The pioneers of this subgenre were Cruachan, Primordial, and Waylander.

Irish music has shown an immense increase in popularity with many attempting to return to their roots. Some contemporary music groups stick closer to a "traditional" sound, including Altan, Téada, Danú, Dervish, Lúnasa, and Solas. Others incorporate multiple cultures in a fusion of styles, such as Afro Celt Sound System and Kíla.

Ireland has done well in the Eurovision Song Contest, being the most successful country in the competition, with seven wins in 1970 with Dana, 1980 and 1987 with Johnny Logan, 1992 with Linda Martin, 1993 with Niamh Kavanagh, 1994 with Paul Harrington and Charlie McGettigan and in 1996 with Eimear Quinn.[83]

Graphic art and sculpture

Irish graphic art and sculpture begins with Neolithic carvings found at sites such as Newgrange[84] and is traced through Bronze age artifacts and the religious carvings and illuminated manuscripts of the mediæval period. During the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, a strong indigenous tradition of painting emerged, including such figures as John Butler Yeats, William Orpen, Jack Yeats and Louis le Brocquy.

Science

Ireland has a rich history in science[85] and is known for its excellence in scientific research conducted at its many universities and institutions. Noted particularly are Ireland's contributions to fiber optics technology and related technologies.

The Irish philosopher and theologian Johannes Scotus Eriugena (c. 815–877) was considered one of the leading intellectuals of his era. Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton CVO OBE, (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish explorer who was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. He along with his expedition made the first ascent of Mount Erebus, and the discovery of the approximate location of the South Magnetic Pole, reached on 16 January 1909 by Edgeworth David, Douglas Mawson, and Alistair MacKay.

Robert Boyle (1627–1691) was an Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, inventor and early gentleman scientist, largely regarded one of the founders of modern chemistry. He is best known for the formulation of Boyle's law, stating that the pressure and volume of an ideal gas are inversely proportional.[85]

Irish physicist John Tyndall (1820-1893) discovered the Tyndall effect, explaining why the sky is blue.

Other notable Irish physicists include Ernest Walton (winner of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics with Sir John Douglas Cockcroft for splitting the nucleus of the atom by artificial means and contributions in the development of a new theory of wave equation),[86] William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (or Lord Kelvin) which the absolute temperature unit Kelvin is named after. Sir Joseph Larmor a physicist and mathematician who made innovations in the understanding of electricity, dynamics, thermodynamics, and the electron theory of matter. His most influential work was Aether and Matter, a theoretical physics book published in 1900.[87] George Johnstone Stoney (who introduced the term electron in 1891), John Stewart Bell (the originator of Bell's Theorem and a paper concerning the discovery of the Bell-Jackiw-Adler anomaly), who was nominated for a Nobel prize, mathematical physicist George Francis FitzGerald, Sir George Gabriel Stokes and many others.[85]

Notable mathematicians include Sir William Rowan Hamilton (mathematician, physicist, astronomer and discoverer of quaternions), Francis Ysidro Edgeworth (influential in the development of neo-classical economics, including the Edgeworth box), John B. Cosgrave (specialist in number theory, former head of the mathematics department of St. Patrick's College and discoverer of a new 2000-digit prime number in 1999 and a record composite Fermat number in 2003) and John Lighton Synge (who made progress in different fields of science, including mechanics and geometrical methods in general relativity and who had mathematician John Nash as one of his students).

The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS) was established in 1940 by the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera.[88] In 1940, physicist Erwin Schrödinger received an invitation to help establish the Institute. He became the Director of the School for Theoretical Physics and remained there for 17 years, during which time he became a naturalised Irish citizen.[88]

Sports

- See also: List of Irish sports people

The most popular sports in Ireland are Gaelic Football and Association Football.[89] Together with Hurling and Rugby, they make up the four biggest team sports in Ireland. Gaelic Football is the most popular in terms of match attendance and community involvement,[90] and the All-Ireland Football Final is the biggest day in Ireland's sporting calendar. Association football, meanwhile, is the most commonly played team sport in Ireland and the most popular sport in which Ireland fields international teams.[91] Furthermore, there is significant Irish interest in the English and (to a lesser extent) Scottish soccer leagues. Many other sports are also played and followed, particularly golf and horse racing but also show jumping, greyhound racing, swimming, boxing, baseball, basketball, cricket, fishing, handball, motorsport, tennis and hockey.

Hurling and Gaelic football, along with camogie, ladies' Gaelic football, handball and rounders, make up the national sports of Ireland, collectively known as Gaelic games. All Gaelic games are governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), with the exception of ladies' Gaelic football and camogie, which are governed by separate organisations. The GAA is organised on an all-Ireland basis with all 32 counties competing. The headquarters of the GAA (and the main stadium) is located at the 82,500[92] capacity Croke Park in north Dublin. Major GAA games are played there, including the semi-finals and finals of the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship and All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship. During the redevelopment of the Lansdowne Road stadium, international rugby and soccer are played there.[93] All GAA players, even at the highest level, are amateurs, receiving no wages (although they are permitted to receive a limited amount of sport-related income from commercial sponsorship.

The Irish Football Association (IFA) was originally the governing body for Association football throughout the island. The game has been played in Ireland since the 1870s (Cliftonville F.C. of Belfast being Ireland's oldest club) and was most popular, especially in its first decades, in Belfast and Ulster. However, some clubs based outside Belfast felt that the IFA largely favoured Ulster-based, Protestant clubs in such matters as selection for the national team. Following an incident in which, despite an earlier promise, the IFA, for security reasons, moved an Irish Cup semi-final replay from Dublin to Belfast,[94] the clubs based in what would soon become the Free State set up a new Football Association of the Irish Free State (FAIFS) - now known as the Football Association of Ireland (FAI) - in 1921. Despite being initially blacklisted by the Home Nations' associations, the FAI was recognised by FIFA in 1923 and organised its first international fixture in 1926 (against Italy). However, both the IFA and FAI continued to select their teams from the whole of Ireland, with some players earning international caps for matches with both teams. Both also referred to their respective teams as "Ireland". In 1950, FIFA directed the associations only to select players from within their respective territories, and in 1953 FIFA further clarified that the FAI's team was to be known only as "Republic of Ireland", and the IFA's team only as "Northern Ireland" (with certain exceptions). Northern Ireland qualified for the World Cup finals in 1958 (reaching the quarter-finals), 1982 and 1986. The Republic qualified for the World Cup finals in 1990 (reaching the quarter-finals), 1994, 2002 and the European Championships in 1988.

The Irish rugby team includes players from north and south, and the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) governs the sport on both sides of the border. Consequently in international rugby, the Ireland team represents the whole island. The Irish rugby team have played in every Rugby World Cup, making the quarter-finals at four of them. Ireland also hosted games during the 1991 and the 1999 Rugby World Cups (including a quarter-final). There are four professional provincial sides that contest the Magners League and Heineken Cup. Irish rugby has become increasingly competitive at both the international and provincial levels since the sport went professional in 1994. During that time, Ulster (1999[95]), Munster (2006[96] and 2008[97]) and Leinster (2009[98]) have won the Heineken Cup. In addition to this, the Irish International side have had increased success in the 6 nations Rugby tournament against Europes other elite sides. This success, including triple crowns (victories over all other home nations in Great Britain)in 2006 and 2007, culminated with a clean sweep of victories, known as a grand slam, in the six nations 2009.[99]

The Ireland cricket team was among the associate nations which qualified for the 2007 Cricket World Cup, where it defeated Pakistan and finished second in its pool, earning a place in the Super 8 stage of the competition. They also competed in the 2009 ICC World Twenty20 after jointly winning the qualifiers. Here they made the Super 8 stage.

The Irish rugby league team is also organised on an all-Ireland basis. The team is made up predominantly of players based in England with Irish family connections, with others drawn from the local competition and Australia. Ireland reached the quarter-finals of the 2000 Rugby League World Cup.

As with rugby and Gaelic games, cricket, golf, tennis, rowing, hockey and most other sports are organised on an all-island basis. Greyhound racing and horse racing are both popular in Ireland: greyhound stadiums are well attended and there are frequent horse race meetings. The Republic is noted for the breeding and training of race horses and is also a large exporter of racing dogs. The horse racing sector is largely concentrated in the central east of the Republic. Boxing is also an all-island sport governed by the Irish Amateur Boxing Association. In 1992, Michael Carruth won a gold medal for boxing in the Barcelona Olympic Games and in 2008 Kenny Egan won a silver medal for boxing in the Olympic Games in Beijing. Irish athletics has seen some development in recent times, with Sonia O'Sullivan winning two notable medals at 5,000 metres; gold at the 1995 World Championships and silver at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Gillian O'Sullivan won silver in the 20k walk at the 2003 World Championships, while sprint hurdler Derval O'Rourke won gold at the 2006 World Indoor Championship in Moscow. Olive Loughnane won a silver medal in the 20k walk in the World Athletics Championships in Berlin in 2009. Golf is a popular sport in Ireland and golf tourism is a major industry. The 2006 Ryder Cup was held at The K Club in County Kildare.[100] Pádraig Harrington became the first Irishman since Fred Daly in 1947 to win the British Open at Carnoustie in July 2007.[101] He successfully defended his title in July 2008 [102] before going on to win the PGA Championship in August.[103] Harrington became the first European to win the PGA Championship in 78 years (Tommy Armour in 1930), and was the first winner from Ireland.

The west coast of Ireland, Lahinch and Donegal Bay in particular, have popular surfing beaches; being fully exposed to the Atlantic Ocean. Donegal Bay is shaped like a funnel and catches West/South-West Atlantic winds, creating good surf - especially in winter. In recent years, Bundoran has hosted European championship surfing. The south-west of Ireland, such as the Dingle Peninsula and Lahinch, also has surf beaches. Scuba diving is increasingly popular in Ireland with clear waters and large populations of sea life, particularly along the western seaboard. There are also many shipwrecks along the coast of Ireland, with some of the best wreck dives being in Malin Head and off the County Cork coast. With thousands of lakes, over 14,000 kilometres (8,700 mi) of fish bearing rivers, and over 3,700 kilometres (2,300 mi) of coastline, Ireland is a popular angling destination. The temperate Irish climate is suited to sport angling. While salmon and trout fishing remain popular with anglers, salmon fishing in particular received a boost in 2006 with the closing of the salmon driftnet fishery. Coarse fishing continues to increase its profile. Sea angling is developed with many beaches mapped and signposted, and in recent times the range of sea angling species has increased.[104]

Places of interest

There are three World Heritage Sites on the island; these are the Bend of the Boyne, Skellig Michael and the Giant's Causeway.[105] [106] A number of other places are on the tentative list, for example the Burren and Mount Stewart.[107]

Some of the most visited sites in Ireland include Bunratty Castle, the Rock of Cashel, the Cliffs of Moher, Holy Cross Abbey and Blarney Castle.[108] Historically important monastic sites include Glendalough and Clonmacnoise, which are maintained as national monuments.[109]

Dublin is the most heavily touristed region,[108] and home to several top attractions such as the Guinness Storehouse and Book of Kells.[108] The west and south west (including the Killarney and Dingle regions in County Kerry, and Galway and the Aran Islands) are also popular tourist destinations.[108]

The stately homes, built during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries in Palladian, Neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles, such as, Castle Ward, Castletown House, Bantry House, are of interest to tourists, and those converted into hotels, such as Ashford Castle, Castle Leslie and Dromoland Castle can be enjoyed as accommodation.[110]

Demographics

Ireland has been inhabited for at least 9,000 years, although little is known about the paleolithic and neolithic inhabitants of the island (other than by inference from genetic research in 2004 that challenges the idea of migration from central Europe and proposes a flow along the Atlantic coast from Spain).[40] Early historical and genealogical records note the existence of dozens of different peoples that may or may not be "mythological" (Cruithne, Attacotti, Conmaicne, Eóganachta, Érainn, Soghain, to name but a few).

During the past 1,000 years or so, Vikings, Normans, Scots and English have all added to the indigenous gene pool.

Ireland's largest religious group is Christianity, of which the largest denomination is the Catholic Church (over 73% for the entire island, and about 86.8%[111] for the Republic), and most of the rest of the population adhere to one of the various Protestant denominations. The largest is the Anglican Church of Ireland. The Irish Muslim community is growing, mostly through increased immigration (see Islam in Ireland). The island also has a small Jewish community (see History of the Jews in Ireland). Over 4% of the Republic's population describe themselves as of no religion.[111]

Ireland has for centuries been a place of emigration, particularly to England, Scotland, the United States, Canada, and Australia. With growing prosperity, Ireland has become a place of immigration instead. Since joining the EU in 2004, Polish people have been the largest source of immigrants (over 150,000)[112] from Central Europe, followed by other immigrants from Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Latvia.[113] According to the 2006 census, 420,000 foreign nationals, or about 10% of the population, lived in the Republic of Ireland.[114] Up to 50,000 eastern European migrant workers had left Ireland towards the end of 2008.[115]

Ireland's high standard of living, high wage economy and EU membership attract migrants from the newest of the European Union countries: Ireland has had a significant number of Romanian immigrants since the 1990s. In recent years, mainland Chinese have been migrating to Ireland in significant numbers (up to 100,000).[116] Nigerians, along with people from other African countries have accounted for a large proportion of the non-European Union migrants to Ireland.

Ireland has been predominantly English-speaking since language shifts durig the nineteenth century, with Irish now the first language only of a small minority,[117] and less than 10% of the population use the language regularly outside of the education system.[118] In the North, English is the de facto official language, but official recognition is afforded to both Irish and Ulster-Scots language. All three languages are spoken on both sides of the border. In recent decades, with the increase of immigration on an all-Ireland basis, many more languages have been introduced, particularly deriving from Asia and Eastern Europe, such as Chinese, Polish, Russian, Turkish, Lithuanian and Latvian.

Cities

After Dublin (1.7m in Greater Dublin), Ireland's largest cities are Belfast (700,000 in Belfast Metropolitan Area), Cork (380,000 in Greater Cork), Derry (110,000 in Derry Urban Area), Limerick (93,321 including suburbs), Galway (71,983), Lisburn (71,465), Waterford (49,240 including suburbs), Newry (27,433), Kilkenny (23,967 incl. suburbs) and Armagh (14,590); there are several towns with larger populations than many of these, but not having historic charters are not recognised as cities.

Transport

Air

There are five main international airports in Ireland: Dublin Airport, Belfast International Airport (Aldergrove), Cork Airport, Shannon Airport and Ireland West Airport (Knock). Dublin Airport is the busiest airport in Ireland,[119] carrying over 22 million passengers per year;[120] a new terminal and runway is now under construction, costing over €2 billion.[121] All provide services to Britain and continental Europe, while Belfast International, Dublin, Shannon, and Ireland West (Knock) also offer a range of transatlantic services. Shannon was decades ago an important stopover on the trans-Atlantic route for refueling operations[122] and, with Dublin, is still one of the Ireland's two designated transatlantic gateway airports.

There are several smaller regional airports: George Best Belfast City Airport, City of Derry Airport (Eglinton), Galway Airport, Kerry Airport (Farranfore), Sligo Airport (Strandhill), Waterford Airport, and Donegal Airport (Carrickfinn). Scheduled services from these regional points are mostly limited to the rest of Ireland and to Great Britain.

Airlines in Ireland include: Aer Lingus (the former national airline of Ireland), Ryanair, Aer Arann, and CityJet.

Ports and harbours

Ireland has ports in the towns of Arklow, Belfast (Port of Belfast), Cork (Cork Harbour), Derry (Londonderry Port), Drogheda, Dublin (Dublin Port), Dundalk, Dún Laoghaire, Foynes, Galway, Larne, Limerick, New Ross, Rosslare Europort, Sligo, Warrenpoint, Waterford (Port of Waterford), and Wicklow.

Ports in the Republic handle 3,600,000 travelers crossing the Irish Sea between Ireland and Britain each year, amounting to 92% of all sea travel.[123] This has been steadily dropping for a number of years (20% since 1999), probably as a result of low cost airlines.

Ferry connections between Britain and Ireland via the Irish Sea include the routes from Swansea to Cork, Fishguard and Pembroke to Rosslare, Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire, Stranraer to Belfast and Larne, and Cairnryan to Larne. There is also a connection between Liverpool and Belfast via the Isle of Man. The world's largest car ferry, Ulysses, is operated by Irish Ferries on the Dublin–Holyhead route.

In addition, Rosslare and Cork run ferries to France.

The vast majority of heavy goods trade is done by sea. Northern Irish ports handle 10 megatonnes (Mt) (11 million short tons) of goods trade with Britain annually, while ports in the south handle 7.6 Mt (8.4 million short tons), representing 50% and 40% respectively of total trade by weight.

Several potential Irish Sea tunnel projects have been proposed, most recently the "Tusker Tunnel" between the ports of Rosslare and Fishguard proposed by the Institution of Engineers of Ireland in 2004.[124][125] A different proposed route is between Dublin and Holyhead, proposed in 1997 by a leading British engineering firm, Symonds, for a rail tunnel from Dublin to Holyhead. Either tunnel, at 80 km (50 mi), would be by far the longest in the world, and would cost an estimated €20bn.

Rail

The railway network in Ireland was developed by various private companies, some of which received (British) Government funding in the late 19th century. The network reached its greatest extent by 1920. The broad gauge of 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in)[126] was eventually settled upon throughout the island, although there were also hundreds of kilometres of 914 mm (3 ft) narrow gauge railways.[126]

Long distance passenger trains in the Republic are managed by Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail) and connect most major towns and cities across the country.

In Dublin, two local rail networks provide transport in the city and its immediate vicinity. The Dublin Area Rapid Transit (DART) links the city centre with coastal suburbs, while a new light rail system named Luas, opened in 2004, transports passengers to the central and western suburbs. Several more Luas lines are planned as well as an eventual upgrade to metro. The DART is run by Iarnród Éireann while the Luas is being run by Veolia under franchise from the Railway Procurement Agency (R.P.A.).

Under the Irish government's Transport 21 plan, reopening the Navan-Clonsilla rail link, the Cork-Midleton rail link and the Western Rail Corridor are amongst plans for Ireland's railways.[127]

In Northern Ireland, all rail services are provided by Northern Ireland Railways (N.I.R.), part of Translink. Services in Northern Ireland are sparse in comparison to the rest of Ireland or Britain. A large railway network was severely curtailed in the 1950s and 1960s (in particular by the Ulster Transport Authority). The current situation includes suburban services to Larne, Newry and Bangor, as well as services to Derry. There is also a branch from Coleraine to Portrush. Waterside Station in Derry is the main railway station for Derry as well as County Donegal, which no longer has a rail network.

Ireland also has one of the largest dedicated freight railways in Europe, operated by Bord na Móna. This company has narrow gauge railways[126] totalling nearly 1,400 kilometres (870 miles).[128]

Roads

Motorists must drive on the left in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. There is an extensive road network, with a (developing) motorway network fanning out from Belfast, Cork and Dublin. Historically, land owners developed most roads and later Turnpike Trusts collected tolls so that as early as 1800 Ireland had a 16,100 km (10,000 mi) road network.[129]

In recent years, the Irish Government launched a new transport plan that is the largest investment project ever in Ireland's transport system - with €34 billion being invested from 2006 until 2015. Work on a number of road projects has already commenced while a number of objectives have been completed.[130] The new transport plan can largely be divided into five categories, Metro / Luas, Heavy rail, roads, buses and airports. The plan was announced on 1 November 2005, by the Minister for Transport, Martin Cullen.[131]

The year 1815 marked the introduction of the first horsecar service from Clonmel to Thurles and Limerick run by Charles Bianconi.[132] Now, the main bus companies are Bus Éireann in the Republic and Ulsterbus, a division of Translink, in Northern Ireland, both of which offer extensive passenger service in all parts of the island. Dublin Bus specifically serves the greater Dublin area, and a further division of Translink called Metro, operates services within the greater Belfast area. Translink also operate Ulsterbus Foyle in the Derry Urban Area.

All speed limit signs in the Republic of Ireland were changed to the metric system in 2005, but some direction signs still show distance in miles.[133] Distance and speed limit signs in Northern Ireland use imperial units.

Ireland's Power Networks

For much of their existence electricity networks in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland were entirely separate. Both networks were designed and constructed independently, but are now connected with three interlinks and also connected through Britain to mainland Europe. The Electricity Supply Board (ESB) in the Republic drove a rural electrification programme in the 1940s until the 1970s. EirGrid is building a HVDC transmission line between Ireland and Britain with a capacity of 500 MW — about 10% of Ireland's peak demand.[134]

The situation in the North is complicated by the issue of private companies not supplying NIE with enough power, while in the South, the ESB has failed to modernise its power stations. In the latter case, availability of power plants has averaged 66% recently, one of the worst such figures in Western Europe.

The natural gas distribution network is also now all-Ireland, with a pipeline linking Gormanston, County Meath, and Ballyclare, County Antrim.[135] Most of Ireland's gas now comes through the interconnectors between Twynholm in Scotland and Ballylumford, County Antrim, Gormanston or Loughshinny, County Dublin with a decreasing supply from the Kinsale field.[136][137] The Corrib Gas Field off the coast of County Mayo has yet to come on-line, and is facing some localized opposition over the controversial decision to refine the gas onshore.

There have been recent efforts in Ireland to use renewable energy such as wind power with large wind farms being constructed in coastal counties such as Donegal, Mayo and Antrim. What will be the world's largest offshore wind farm is currently being developed at Arklow Bank off the coast of Wicklow. It is predicted to generate 10% of Ireland's power needs when it is complete. These constructions have in some cases been delayed by opposition from locals, most recently on Achill Island, some of whom consider the wind turbines to be unsightly. Another issue in the Republic of Ireland is the failure of the aging network to cope with the varying availability of power from such installations. The ESB's Turlough Hill is the only power storage facility in Ireland.[138]

Economy

Ireland was periodically troubled by emigration until the 1980s. About half a million people left Ireland in the 1950s alone.[139] These problems virtually disappeared over the course of the 1990s, which saw the beginning of unprecedented economic growth, in a phenomenon known as the "Celtic Tiger."[140] In 2005, Ireland was ranked the best place to live in the world, according to a "quality of life" assessment by Economist magazine.[141] Ireland has been in recession since second quarter of 2008 and some commentators have claimed it is in a depression.[142][143] In August 2009, the unemployment rate for Ireland was 12.5%.[144]

See also

Notes

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ei.html

- ^ a b Nolan, Professor William. "Geography of Ireland". Government of Ireland. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Population and Migration Estimates April 2009" (PDF). CSO. 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ "NI's population passes 1.75m mark". News. BBC News. December 2000. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ "Migration pushes population in the North up to 1.75 million". Breaking News. Demography and Methodology Branch, NISRA. July 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ "Irish-Catholic Immigration to America". Immigration. Library of Congress. 7 May 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Olson, p. 58.

- ^ Magee, p. 108.

- ^ Crawford, John G. (1993). Anglicizing the Government of Ireland: The Irish Privy Council & the Expansion of Tudor Rule 1556-1578. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0716524988.

- ^ "Ulster county divisions". Comhairle Uladh CLG. GAA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ^ "NI Tourist board comprising Counties Armagh and Down". Armagh and Down. NI Tourist Board. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ^ "Population by Province". Population. CSO. 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ "National Competitiveness Council Submission on the National Development Plan 2007-2013" (PDF). Submission. National Competitiveness Council. October 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - ^ "Agreement Reached in the Multi-party Negotiations". Agreement. Northern Ireland Assembly. 10 April 1998. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "About SEMO". Publication. Single Electricity Market Operator (SEMO). 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "DUP minister expresses support for single gas market". Newspaper. Belfast Telegraph. 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ "Ordnance Survey FAQs". Ordnance Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- ^ "Kerry: Key Facts". Discoverireland.ie. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ "Nature and Scenery". Ireland's landscape. Discover Ireland (Official Ireland tourism website). Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Ireland". Encarta Encyclopedia. Micsosoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Climate of Ireland". Climate. Met Éireann. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ a b "Rainfall". Climate. Met Éireann. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "Temperature in Ireland". Climate. Met Éireann. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "Geology of Ireland". Geology for Everyone. Geological Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "Bedrock Geology of Ireland" (PDF). Geology for Everyone. Geological Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "Geology of Kerry-Cork - Sheet 21". Maps. Geological Survey of Ireland. 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ Karst Working Group 2000 (2000). "The Burren: Karst of Ireland - the Burren". County Clare Library. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Irish Natural Gas Market". Story of Natural Gas. Bord Gáis. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ Shannon, P. (2001). The Petroleum Exploration of Ireland's Offshore Basins. London: Geological Society Publishing House: Lyell Collection—Special Publications. p. 2. ISBN 1423711637.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Providence sees Helvick oil field as key site in Celtic Sea". Irish Examiner. 2000-07-17. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ a b "Land cover and land use". Environmental Assessment. Environmental Protection Agency. 2000. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "National forestation statistics". Forest Facts. Coillte Teoranta. 2007-01-05. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ^ "Invasive Alien Species in Northern Ireland - Spartina anglica, Common Cord-grass". National Museums Northern Ireland. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ Guiry, M.D.; Nic Dhonncha, E.N (2001), The marine macroalgae of Ireland : biodiversity and distribution in Marine Biodiversity in Ireland and Adjacent Waters, vol. Proceedings of a Conference 26–27 April 2001 (Publication no. 8 ed.), Belfast: Ulster Museum

- ^ Minchin, D. (2001), Biodiversity and Marine Invaders (Appendix): in Marine Biodiversity in Ireland and Adjacent Waters, vol. Proceedings of a Conference 26–27 April 2001 (Publication no. 8 ed.), Belfast: Ulster Museum

- ^ a b CAP reform - a long-term perspective for sustainable agriculture, European Commission, retrieved 2007-07-30

- ^ Roche, Dick (2006-11-08), National Parks, vol. 185, Seanad Éireann, retrieved 2007-07-30 Seanad Debate involving Former Minister for Environment Heritage and Local Government

- ^ "Heritage Ireland - Céide Fields". Heritage Ireland. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ "The Neolithic Stone Age in Ireland : Farming". The Ireland Story. Wesley Johnson. 2000. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ a b Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006-10-21). "Myths of British ancestry". Prospect Magazine (127). Prospect Magazine. ISSN 1359-5024. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mascheretti, Silvia (2003-08-07). "How did pygmy shrews colonize Ireland? Clues from a phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 270 (1524). Royal Society: 1593. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2406. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hibernia". Roman Empire. United Nations of Roma Victrix. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ O'Hart, John (1892). Irish Pedigrees; Or, The Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation. Dublin: J. Duffy and Co. p. 725.

- ^ "Scotia". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition 2001–05. Encyclopedia.com. 2007. Retrieved 20089-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/section?content=a791562641&fulltext=713240928

- ^ "The Geography of Ptolemy". Roman-Britain.org. 2003-04-23. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLO.

- ^ Roe, Harry (1999). Tales of the Elders of Ireland. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Michael Roberts; et al. (1957). Early Irish history and pseudo-history. Bowes & Bowes Michigan University Press.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ De Paor, Liam (1993). Saint Patrick's World: The Christian Culture of Ireland's Apostolic Age. Dublin: Four Courts, Dublin. p. 78, 79. ISBN 1-85182-144-9.

- ^ a b Cahill, Tim (1996). How the Irish Saved Civilization. Anchor Books. ISBN 0385418493.

- ^ Dowley, Tim; et al., eds. (1977). Eerdman's Handbook to the History of Christianity. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8028-3450-7.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (2005-01-25). "Scion of traitors and warlords: why Bush is coy about his Irish links". World News. The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Curtis, Edmund (2002). A History of Ireland from Earliest Times to 1922. New York: Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 0 415 27949 6.

- ^ "Laws that Isolated and Impoverished the Irish". Nebraska Department of Education.

- ^ "The curse of Cromwell". A Short History of Ireland. BBC Northern Ireland. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery". University of Minnesota Law School. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Ward, Alan J. (1994). The Irish Constitutional Tradition: Responsible Government and Modern Ireland, 1782-1992. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-81320-784-3.

- ^ "The Irish Potato Famine". Digital History. 2008-11-07. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Vallely, Paul (2006-04-25). "1841: A window on Victorian Britain - This Britain". The Independent. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ Quinn, Eamon (2007-08-19). "Ireland Learns to Adapt to a Population Growth Spurt". Europe. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ Kee, Robert (1972). The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson. pp. 376–400. ISBN 029717987X.

- ^ Kee, Robert (1972). The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson. pp. 478–530. ISBN 029717987X.