Daskalogiannis

Ioannis Vlachos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Ιωάννης Βλάχος |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | 1722 or 1730 Anopolis, Crete, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 17 June 1771 (age 40–49) Heraklion, Crete, Ottoman Empire |

Ioannis Vlachos (Greek: Ιωάννης Βλάχος), better known as Daskalogiannis (Δασκαλογιάννης; 1722/30 – 17 June 1771), was a wealthy shipbuilder and shipowner who led a Cretan revolt against Ottoman rule in the 18th century.[1][2]

Life and activity

[edit]

Ioannis Vlachos was born in Anopolis village in Sfakia, a then semi-autonomous region of Crete, in 1722 or 1730. His father, who was also a wealthy shipowner, sent him to be educated abroad. Due to his education, his compatriots called him "Daskalos" (teacher), hence his nickname Daskalogiannis, literally "John the Teacher." He is referred to as a town clerk in 1750, as chairman of the region of Sfakia in 1765, and as the owner of four, three-mast merchant ships.[3] These would have sailed from Omprosgialos and the gulf of Loutro.[2]

Daskalogiannis knew Panagiotis Benakis at Mani and it is likely that Benakis introduced him to Count Orlov who Catherine the Great had sent to the Peloponnese in 1769 to instigate a revolt there. Many men from Sfakia also participated in the revolt which Orlov instigated in the Peloponnese.[3]

Leader of revolt

[edit]In early 1770, he was contacted by Russian emissaries, who hoped to instigate a revolt amongst the Greek subjects of the Ottoman Empire. Daskalogiannis agreed to fund and organize a rebellion in Sfakia against the Turkish authorities when the Russian emissaries promised to support him. In the spring of 1770, Daskalogiannis made preparations for the revolt; he brought together men, rifles, and supplies and had defenses built at strategic locations.[3] However, the Russian fleet in the Aegean, under Count Orlov, did not sail for Crete, and the revolt was left to rely on its own resources. The uprising began on 25 March 1770, the rebels attacked the areas of Kydonia, Apokoronas and Agios Vasilios, north east of Lefka Ori. The rebels at first, put the Turks to flight and parts of Crete had the attributes of an independent nation, including its own coins minted in a cave near Hora Sfakion. However, in a matter of only a short time the Turks had gathered together their troops again, and as early as May they had an army of 40,000 men ready at the village of Vrysses.[4][self-published source?]

When the Turks attacked Daskalogiannis and his men on the Krapi plateau, the rebels suffered a crushing defeat and had to take refuge in the high mountains. The Turks held the rebels in check, while they destroyed many of the villages in the area, scattered the inhabitants' flocks of sheep, looted the province, captured many inhabitants and sold them in the slave market in Chándakas (Iraklion). Daskalogiannis' uncle, the rural dean, was also taken prisoner.[4][self-published source?]

The Russian intervention, promised to Daskalogiannis, failed to materialize and the uprising did not spread to the lowlands.[5] On 18 March 1771 the Turks gave the rebels an ultimatum. If they surrendered they would be granted safe passage, but the ultimatum was simultaneously accompanied by a document with peace terms. The document contained 12 items:[4][self-published source?]

1. They were to pay the taxes they had refused to pay the year before. 2. They were to surrender their arms and provisions. 3. They were to surrender their leaders, who would be taken to Iraklion for legal proceedings. 4. They were no longer to have neither contact with nor provision the Christian ships approaching their harbours. 5. They were to assist in arresting the crews on the Christian ships and take them to Iraklion. 6. The judiciary in Sfakia was to be managed by a justice of the peace appointed by the Turkish government in Iraklion. 7. The churches were not to be either repaired or restored. As were no new churches to be built. 8. They were to pay tithe according to the sultans' firman (statutory instrument). 9. No tall houses (castle towers) were to be built, and no Christian symbols were allowed on the existing buildings. 10. It was prohibited to hold religious celebrations, as was ringing forbidden. 11. The captured Muslims were to be released. 12. The Sfakiots were to wear the specific clothes for subjugated Greeks.

When Daskalogiannis realized that the battle was lost, he surrendered to the Turks in the hope that it would ease the situation for his compatriots. It is also said that his brother, Nikolós Sgouromállis, who had already been taken prisoner, was forced to write him a letter in which he pointed out the Turks' good will.

Daskalogiannis was taken to Iraklion together with his most trusted men, but rather than keeping the promise of the ultimatum the pasha of the town had in place a cruel punishment. On 17 June 1771 Daskalogiannis was, in the full daylight of publicity, tortured, skinned alive and then beaten to death, an ordeal that he endured in complete silence.[6] His brother was forced to watch the torture which drove him insane.[7]

Family

[edit]Daskalogiannis was married to Sgouromallini, their daughters Anthousa and Maria Daskalogianni fought alongside their father during the course of the revolt. Sgouromallini and Anthousa were killed in its aftermath. Maria was enslaved and given to the Ottoman vizier, who in turn gifted to the teftedar of Heraklion. The latter married Maria, without forcing her to convert to Islam (according to the custom of the time) and the two moved to Constantinople. After her husband's death in 1816, Maria inherited a considerable amount of money donating to the Greek revolutionaries following the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence.[8]

Legacy

[edit]Daskalogiannis was immortalized in several folk tales and songs, the most prominent of which is the celebrated epic ballad by Barba-Pantzelios, a poor cheese-maker from Mouri – To tragoudi tou Daskalogianni of 1786:[3][9]

- …Φτάνουν στο Φραγκοκάστελο και στον πασά ποσώνου,

- κι εκείνος δούδει τ' όρντινο κι ευτύς τσοι ξαρματώνου.

- Ούλους τσοι ξαρματώσασι και τσοι μπισταγκωνίζου

- και τότες δα το νιώσασι πως δεν ξαναγυρίζου.

- ...They arrive at Frangokastello and surrender to the pasha,

- and he gives the order to disarm them at once.

- All of them were disarmed and ill at ease,

- for now they sensed that they would never go home.

Tradition states that before Daskalogiannis and his few men made their last stand against the Ottomans, they danced the war dance Pentozalis.

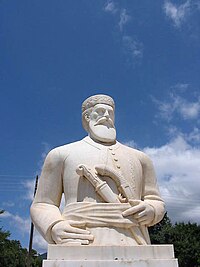

The international airport of Chania (CHQ/LGSA) bears Daskalogiannis' name.[10] A memorial statue can be seen in his hometown Anopolis. One of the regular ferries in the Crete southeast routes is named the Daskalogiannis.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Kohn, George C., ed. (2006). Dictionary of Wars (3rd ed.). New York: Infobase. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2024 – via Scribd.

- ^ a b Detorakis 1988, p. 357.

- ^ a b c d Detorakis 1988, p. 358.

- ^ a b c "History – The Turkish Period: Daskalogiannis". Kretakultur English. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Detorakis 1988, p. 359.

- ^ Papoutsakis, Niko (22 May 2001). "Daskalogiannis: Skinned Alive by the Turks". Stigmes Online. Archived from the original on 22 May 2001. Retrieved 28 November 2024.

- ^ Detorakis 1988, p. 361.

- ^ Xiradaki, Koula (1995). Γυναίκες του 21 [Women of 21] (in Greek). Athens: Dodoni. pp. 357–360. ISBN 960-248-781-X.

- ^ Beaton, Roderick (2004). Folk Poetry of Modern Greece. Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–159. ISBN 978-0-521-60420-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hatzipanagos, George. "Ioannis Daskalogiannis International Airport". Greek Airports. Hellenic Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Detorakis, Theocharis (1988). "Η Τουρκοκρατία στην Κρήτη" [Turkish Rule in Crete]. In Panagiotakis, Nikolaos M. (ed.). Κρήτη: Ιστορία καί Πολιτισμός [Crete: History and Culture] (in Greek). Vol. II. Heraklion: Vikelea Municipial Library. pp. 333–436. ISBN 978-0-00-797002-5.

- 1720s births

- 1771 deaths

- 18th-century Greek people

- 18th-century rebels

- 18th-century executions by the Ottoman Empire

- 1770 in the Ottoman Empire

- Executed Greek people

- Greek torture victims

- Executed revolutionaries

- Greek rebellions

- Greek revolutionaries

- People executed for treason against the Ottoman Empire

- People executed by flaying

- People from Sfakia

- Rebels from the Ottoman Empire

- Orlov revolt