Operation Demetrius

| Operation Demetrius | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Troubles and Operation Banner | |

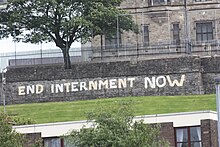

The entrance to Compound 19, one of the sections of Long Kesh internment camp | |

| Location | |

| Objective | Arrest of suspected Irish republican militants |

| Date | 9–10 August 1971 04:00 – ? (UTC+01:00) |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome |

|

| Casualties | (see below) |

Operation Demetrius was a British Army operation in Northern Ireland on 9–10 August 1971, during the Troubles. It involved the mass arrest and internment (imprisonment without trial) of people suspected of being involved with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which was waging an armed campaign for a united Ireland against the British state. It was proposed by the Unionist government of Northern Ireland and approved by the British Government. Armed soldiers launched dawn raids throughout Northern Ireland and arrested 342 in the initial sweep, sparking four days of violence in which 20 civilians, two IRA members and two British soldiers were killed. All of those arrested were Irish republicans and nationalists, the vast majority of them Catholics. Due to faulty and out-of-date intelligence, many were no longer involved in republican militancy or never had links with the IRA.[1] Ulster loyalist paramilitaries were also carrying out acts of violence, which were mainly directed against Catholics and Irish nationalists, but no loyalists were included in the sweep.[1]

The introduction of internment, the way the arrests were carried out, and the abuse of those arrested, led to mass protests and a sharp increase in violence. Amid the violence, about 7,000 people fled or were forced out of their homes.

The policy of internment lasted until December 1975 and during that time 1,981 people were interned;[2] 1,874 were nationalist, while 107 were loyalist. The first loyalist internees were detained in February 1973.[1]

The interrogation techniques used on some of the internees were described by the European Commission of Human Rights in 1976 as torture, but the superior court, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), ruled on appeal in 1978 that while the techniques were "inhuman and degrading", they did not constitute torture in this instance.[3] It was later revealed that the British government had withheld information from the ECHR and that the policy had been authorized by British government ministers.[4] In light of the new evidence, in 2014 the Irish government asked the ECHR to revise its judgement,[5] but the ECHR eventually declined the request. In 2021, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom found that the use of the five techniques amounts to torture.[6]

Background and planning

[edit]Internment had been used several times in Ireland during the 20th century, but had not previously been used during the Troubles, which began in the late 1960s. Ulster loyalist paramilitaries, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), had been engaged in a low-level violent campaign since 1966. After the August 1969 riots, the British Army was deployed on the streets to bolster the police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Up until this point, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had been largely inactive. However, as the violence worsened, the IRA was divided over how to deal with it. It split into two factions, the Provisional IRA and Official IRA. In 1970–71, the Provisionals began a guerrilla campaign against the British Army and the RUC. The Officials' policy was more defensive.[7] During 1970–71, there were numerous clashes between state forces and the two wings of the IRA, and between the IRAs and loyalists. Most loyalist attacks were directed against Catholic civilians, but they also clashed with state forces and the IRA on a number of occasions.[7]

The idea of re-introducing internment for Irish republican militants came from the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, headed by Prime Minister Brian Faulkner. It was agreed to re-introduce internment at a meeting between Faulkner and British Prime Minister Edward Heath on 5 August 1971. The goal of internment was to weaken the IRA and reduce their attacks, but it was also hoped that tougher measures against the IRA would prevent a loyalist backlash and the collapse of Faulkner's government.[8][9] The British cabinet recommended "balancing action", such as the arrest of loyalist militants, the calling in of weapons held by (generally unionist) rifle clubs in Northern Ireland, and an indefinite ban on parades (most of which were held by unionist/loyalist groups such as the Orange Order). However, Faulkner argued that a ban on parades was unworkable, that the rifle clubs posed no security risk, and that there was no evidence of loyalist terrorism.[10] It was eventually agreed that there would be a six-month ban on parades but no interning of loyalists, and that internment would go ahead on 9 August.[7]

On the initial list of those to be arrested, which was drawn up by RUC Special Branch and MI5, there were 450 names, but only 350 of these were found. Key figures on the list, and many who never appeared on them, had got wind of the swoop before it began. The list also included leaders of the non-violent Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and People's Democracy such as Ivan Barr and Michael Farrell.

Ulster loyalist paramilitaries were also carrying out attacks, mainly directed against Catholics and Irish nationalists. However, security officials advised ministers that loyalists did not represent an immediate and serious threat to the security of the state or the criminal justice system, and no loyalists were interned.[1] Tim Pat Coogan has commented:

What they did not include was a single loyalist. Although the UVF had begun the killing and bombing, this organisation was left untouched, as were other violent loyalist satellite organisations such as Tara, the Shankill Defence Association and the Ulster Protestant Volunteers. Faulkner was urged by the British to include a few Protestants in the trawl but, apart from two republicans, he refused.[11]

Faulkner himself later wrote, "The idea of arresting anyone as an exercise in political cosmetics was repugnant to me".[12]

Internment was planned and implemented from the highest levels of the British government. Specially trained personnel were sent to Northern Ireland to familiarize the local forces in what became known as the 'five techniques', methods of interrogation described by opponents as "a euphemism for torture".[13] The available evidence suggests that some members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, trained in civilian policing, were unwilling to use such methods. In an internal memorandum dated 22 December 1971, one Brigadier Lewis reported to his superiors in London on the state of intelligence-gathering in Northern Ireland, saying that he was "very concerned about lack of interrogation in depth" by the RUC and that "some Special Branch out-station heads are not attempting to screw down arrested men and extract intelligence from them". However, he wrote that his colleagues "were due to do a quick visit by helicopter to these out-stations... to read the riot act".[14]

Legal basis

[edit]The internments were initially carried out under Regulations 11 and 12 of 1956 and Regulation 10 of 1957 (the Special Powers Regulations), made under the authority of the Special Powers Act. The 1922 Special Powers Act (also known as the "Flogging Act") was renewed annually, in 1928 was renewed for five year and made permanent in 1933. The Act was repealed 1973.[15] The Detention of Terrorists Order of 7 November 1972, made under the authority of the Temporary Provisions Act, was used after direct rule was instituted.

Internees arrested without trial pursuant to Operation Demetrius could not complain to the European Commission of Human Rights about breaches of Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) because on 27 June 1957, the UK lodged a notice with the Council of Europe declaring that there was a "public emergency within the meaning of Article 15(1) of the Convention".[16]

Operation and immediate aftermath

[edit]

Operation Demetrius began on Monday 9 August at 4 am and progressed in two parts:

- Arrest and movement of the detainees to one of three regional holding centers: Girdwood in Belfast, Ballykinler in County Down, or Magilligan in County Londonderry;

- The process of identification and questioning, leading either to release of the detainee or movement into detention at Crumlin Road prison or aboard HMS Maidstone, a prison ship in Belfast Harbour.[17]

In the first wave of raids across Northern Ireland, 342 people were arrested.[18] Many of those arrested reported that they and their families were assaulted, verbally abused and threatened by the soldiers. There were claims of soldiers smashing their way into houses without warning and firing baton rounds through doors and windows. Many of those arrested also reported being ill-treated during their three-day detention at the holding centres. They complained of being beaten, verbally abused, threatened, harassed by dogs, denied sleep, and starved. Some reported being forced to run a gauntlet of baton-wielding soldiers, being forced to run an 'obstacle course', having their heads forcefully shaved, being kept naked, being burnt with cigarettes, having a sack placed over their heads for long periods, having a rope kept around their necks, having the barrel of a gun pressed against their heads, being dragged by the hair, being trailed behind armoured vehicles while barefoot, and being tied to armoured trucks as a human shield.[19][20] Some were hooded, beaten and then thrown from a helicopter. They were told they were hundreds of feet in the air, but were actually only a few feet from the ground.[21]

The operation sparked an immediate upsurge of violence, the worst since the August 1969 riots.[18] The British Army came under sustained attack from the IRA and Irish nationalist rioters, especially in Belfast. According to journalist Kevin Myers: "Insanity seized the city. Hundreds of vehicles were hijacked and factories were burnt. Loyalist and IRA gunmen were everywhere".[22] People blocked roads and streets with burning barricades to stop the British Army entering their neighbourhoods. In Derry, barricades were again erected around Free Derry and "for the next 11 months these areas effectively seceded from British control".[23] Between 9 and 11 August, 24 people were killed or fatally wounded: 20 civilians (14 Catholics, 6 Protestants), two members of the Provisional IRA (shot dead by the British Army), and two members of the British Army (shot dead by the Provisional IRA).[24]

Of the civilians killed, 17 were shot by the British Army and the other three were killed by unknown attackers.[24] In west Belfast's Ballymurphy housing estate, 11 Catholic civilians were killed by the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment over two days in what became known as the Ballymurphy Massacre. Another flashpoint was Ardoyne in north Belfast, where soldiers shot dead three people on 9 August.[24] Sectarian violence also flared between Protestants and Catholics. Many Protestant families fled Ardoyne and about 200 Protestants burnt their own homes as they left, lest they "fall into Catholic hands".[25] Protestant and Catholic families fled "to either side of a dividing line, which would provide the foundation for the permanent peaceline later built in the area".[22] Catholic homes were burnt in Ardoyne and elsewhere too.[25] About 7,000 people, most of them Catholics, were left homeless.[25] About 2,500 Catholic refugees fled south of the border to the Republic of Ireland, where new refugee camps were set up.[25]

By 13 August, media reports indicated that the violence had begun to wane, seemingly due to exhaustion on the part of the IRA and security forces.[26] On 15 August, the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) announced that it was starting a campaign of civil disobedience in response to the introduction of internment. By 17 October, it was estimated that about 16,000 households were withholding rent and rates for council houses as part of the campaign of civil disobedience.[18]

On 16 August, over 8,000 workers went on strike in Derry in protest at internment. Joe Cahill, then Chief of Staff of the Provisional IRA, held a press conference during which he claimed that only 30 Provisional IRA members had been interned.[18]

On 22 August, in protest against internment, about 130 Irish nationalist/republican councillors announced that they would no longer sit on district councils. The SDLP also withdrew its representatives from a number of public bodies.[18] On 19 October, five Northern Ireland Members of Parliament (MPs) began a 48-hour hunger strike against internment. The protest took place near 10 Downing Street in London. Among those taking part were John Hume, Austin Currie, and Bernadette Devlin.[18] Protests would continue until internment was ended in December 1975.

Long-term effects

[edit]

The backlash against internment contributed to the decision of the British Government to suspend the Northern Ireland Government and Parliament and replace it with direct rule from Westminster, under the authority of a British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. This took place on 23 March 1972.[27]

Following the suspension of the Northern Ireland Government, internment was continued with some changes by the direct rule administration until 5 December 1975. During this time a total of 1,981 people were interned: 1,874 were from an Irish nationalist background, while 107 were from a unionist background.[1]

Historians generally view the period of internment as inflaming sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland, while failing in its goal of arresting key members of the IRA. Senator Maurice Hayes, Catholic Chairman of the Northern Ireland Community Relations Commission at the time, has described internment as "possibly the worst of all the stupid things that government could do".[28] A review by the British Ministry of Defence (MoD) assessed internment overall as "a major mistake". Others, however, have taken a more nuanced view, suggesting that the policy was not so much misconceived in principle as badly planned and executed. The MoD review points to some short-term gains, maintaining that Operation Demetrius netted 50 Provisional IRA officers, 107 IRA volunteers, and valuable information on the IRA and its structures, leading to the discovery of substantial arms and explosives dumps.[29]

Many of the people arrested had no links with the IRA, but their names appeared on the list through haste and incompetence. The list's lack of reliability and the arrests that followed, complemented by reports of internees being abused,[10] led to more nationalists identifying with the IRA and losing hope in non-violent methods. After Operation Demetrius, recruits came forward in huge numbers to join the Provisional and Official wings of the IRA.[25] Internment also led to a sharp increase in violence. In the eight months before the operation, there were 34 conflict-related deaths in Northern Ireland. In the four months following it, 140 were killed.[25] A serving officer of the British Royal Marines declared:

It (internment) has, in fact, increased terrorist activity, perhaps boosted IRA recruitment, polarised further the Catholic and Protestant communities and reduced the ranks of the much needed Catholic moderates.[30]

In terms of loss of life as well as number of attacks, 1972 was the most violent year of the Troubles. The fatal march on Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972), when 14 unarmed protesters were shot dead by British paratroopers, was an anti-internment march.[31]

Interrogation of internees

[edit]All of those arrested were interrogated by the British Army and RUC. However, twelve internees were then chosen for further "deep interrogation", using sensory deprivation. This took place at a secret interrogation centre, which was later revealed to be Shackleton Barracks, outside Ballykelly. In October, a further two internees were chosen for deep interrogation. These fourteen became known as "the Hooded Men", or "the Guineapigs".

After undergoing the same treatment as the other internees, the men were hooded, handcuffed and flown to the base by helicopter. On the way, soldiers severely beat them and threatened to throw them from the helicopter. When they arrived they were stripped naked, photographed, and examined by a doctor.[32]

For seven days, when not being interrogated, they were kept hooded and handcuffed in a cold cell and subjected to a continuous loud hissing noise. Here they were forced to stand in a stress position for many hours and were repeatedly beaten on all parts of their body. They were deprived of sleep, food and drink. Some of them also reported being kicked in the genitals, having their heads banged against walls, being shot at with blank rounds, and being threatened with injections. The result was severe physical and mental exhaustion, severe anxiety, depression, hallucinations, disorientation and repeated loss of consciousness.[32][33]

The interrogation methods used on the men became known as the 'five techniques'. Training and advice regarding the five techniques came from senior intelligence officials in the British government. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) defined the five techniques as follows:

- wall-standing: forcing the detainees to remain for periods of some hours in a "stress position", described by those who underwent it as being "spreadeagled against the wall, with their fingers put high above the head against the wall, the legs spread apart and the feet back, causing them to stand on their toes with the weight of the body mainly on the fingers";

- hooding: putting a black or navy coloured bag over the detainees' heads and, at least initially, keeping it there all the time except during interrogation;

- subjection to noise: pending their interrogations, holding the detainees in a room where there was a continuous loud and hissing noise;

- deprivation of sleep: pending their interrogations, depriving the detainees of sleep;

- deprivation of food and drink: subjecting the detainees to a reduced diet during their stay at the centre and pending interrogations.

The fourteen Hooded Men were the only internees subjected to the full five techniques. However, over the following months, some internees were subjected to at least one of the five techniques, as well as other interrogation methods. These allegedly included waterboarding,[34] electric shocks, burning with matches and candles, forcing internees to stand over hot electric fires while beating them, beating and squeezing of the genitals, inserting objects into the anus, injections, whipping the soles of the feet, and psychological abuse such as Russian roulette.[35]

Parker Report

[edit]When the interrogation techniques used on the internees became known to the public, there was outrage at the British government, especially from Irish nationalists. In response, on 16 November 1971, the British government commissioned a committee of inquiry chaired by Lord Parker (the Lord Chief Justice of England) to look into the legal and moral aspects of the 'five techniques'.

The "Parker Report"[36] was published on 2 March 1972 and found the five techniques to be illegal under domestic law:

10. Domestic Law ... (c) We have received both written and oral representations from many legal bodies and individual lawyers from both England and Northern Ireland. There has been no dissent from the view that the procedures are illegal alike by the law of England and the law of Northern Ireland. ... (d) This being so, no Army Directive and no Minister could lawfully or validly have authorized the use of the procedures. Only Parliament can alter the law. The procedures were and are illegal.

On the same day (2 March 1972), British Prime Minister Edward Heath stated in the House of Commons:

[The] Government, having reviewed the whole matter with great care and with reference to any future operations, have decided that the techniques ... will not be used in future as an aid to interrogation ... The statement that I have made covers all future circumstances.[37]

As foreshadowed in the Prime Minister's statement, directives expressly forbidding the use of the techniques, whether alone or together, were then issued to the security forces by the government.[37] The five techniques were still being used by the British Army in 2003 as a means for training soldiers to resist harsh interrogation if captured.[38]

Irish Government

[edit]The Irish Free State government had used internment during the Irish Civil War in the 1920s and the Irish government again used it during the IRA's campaign in the 1950s. In December 1970, Justice Minister Des O'Malley had announced that the policy was again under consideration. The Irish Times reported that if internment were introduced in Northern Ireland, it would follow in the Republic almost at once.[39] However, when British Ambassador John Peck asked Taoiseach Jack Lynch on 30 July 1971 about this, Lynch replied that he had no grounds for introducing internment, and that if he did his government would collapse. Lynch also advised Peck to consider the consequences carefully.[40]

After Operation Demetrius, the Irish government pushed for radical changes in how Northern Ireland was governed. Paddy Hillery, the Irish Minister for External Affairs, met British Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in London on 9 August to demand that the Unionist government should be replaced by a power-sharing coalition with 50/50 representation for the nationalist and unionist populations. This was a significant break from the Republic's previous position, which had been to press for unification. British Prime Minister Ted Heath's reaction was a dismissive telegram telling Lynch to mind his own business. He later accepted the advice of his own diplomats that humiliating Lynch and Hillery would make it less likely that they would co-operate in tackling the IRA. Thereafter, Heath took a more conciliatory tone. He invited Lynch for a two-day summit at Chequers, the Prime Minister’s official country residence, on 6–7 September 1971. This encounter seems to have changed his view of the problem: from then on, Heath took the view that there could be no lasting solution to the Northern Ireland problem without the co-operation of the Irish government, and that the Irish nationalist population in Northern Ireland should have full participation in the government of Northern Ireland. In that sense, the illegal actions of the British government and armed forces during internment and the violent reaction against it led to a profound transformation in British policy.[41]

Irish ministers made the most of the leverage that the torture allegations had given them. Hugh McCann, a senior Irish diplomat, noted the tactical advantage the Irish government could gain through taking a case against the UK before the European Court, which would take years to be adjudicated: it would "make the British much more careful in their handling of detainees... To the extent that this would slow down their gathering of intelligence information, it would make it more difficult for them to make progress in the direction of a military solution. If they succeeded in containing the situation from a military point of view, there would be less incentive for them to take unpalatable political action".[42] The implications are (a) that the Irish government recognised the value of the intelligence which the British were acquiring (albeit illegally), and (b) that Dublin had a stake in impeding Britain's attempt to overcome the IRA by military means, at least until the British had implemented radical constitutional reforms opening up the path to Irish unification.

European Commission of Human Rights

[edit]The Irish Government, on behalf of the men who had been subject to the five techniques, took a case to the European Commission on Human Rights (Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788–94 (Eur. Comm'n of Hum. Rts.)). The Commission stated that it

unanimously considered the combined use of the five methods to amount to torture, on the grounds that (1) the intensity of the stress caused by techniques creating sensory deprivation "directly affects the personality physically and mentally"; and (2) "the systematic application of the techniques for the purpose of inducing a person to give information shows a clear resemblance to those methods of systematic torture which have been known over the ages ... a modern system of torture falling into the same category as those systems applied in previous times as a means of obtaining information and confessions.[43][44]

European Court of Human Rights

[edit]The commission's findings were appealed. In 1978, in the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) trial Ireland v. the United Kingdom (Case No. 5310/71),[45] the court ruled:

167. ... Although the five techniques, as applied in combination, undoubtedly amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment, although their object was the extraction of confessions, the naming of others and/or information and although they were used systematically, they did not occasion suffering of the particular intensity and cruelty implied by the word torture as so understood. ... 168. The Court concludes that recourse to the five techniques amounted to a practice of inhuman and degrading treatment, which practice was in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights Article 3 (art. 3).

On 8 February 1977, in proceedings before the ECHR, and in line with the findings of the Parker Report and British Government policy, the Attorney-General of the United Kingdom stated:

The Government of the United Kingdom have considered the question of the use of the 'five techniques' with very great care and with particular regard to Article 3 (art. 3) of the Convention. They now give this unqualified undertaking, that the 'five techniques' will not in any circumstances be reintroduced as an aid to interrogation.

Later developments

[edit]In 2013, declassified documents revealed the existence of the interrogation centre at Ballykelly. It had not been mentioned in any of the inquiries. Human rights group the Pat Finucane Centre accused the British Government of deliberately hiding it from the inquiries and the European Court of Human Rights.[46] In June 2014, an RTÉ documentary entitled The Torture Files uncovered a letter from the British Home Secretary Merlyn Rees in 1977 to the then British Prime Minister James Callaghan. It confirmed that a policy of 'torture' had in fact been authorized by British Government ministers—specifically the Secretary for Defence Peter Carrington—in 1971, contrary to the knowledge of the Irish government or the ECHR. The letter states: "It is my view (confirmed by Brian Faulkner before his death) that the decision to use methods of torture in Northern Ireland in 1971/72 was taken by ministers – in particular Lord Carrington, then secretary of state for defence".[4][47]

Following the 2014 revelations, the President of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams, called on the Irish government to bring the case back to the ECHR because the British government, he said, "lied to the European Court of Human Rights both on the severity of the methods used on the men, their long term physical and psychological consequences, on where these interrogations took place and who gave the political authority and clearance for it".[48] On 2 December 2014, the Irish government announced that, having reviewed the new evidence and following requests from the survivors, it had decided to officially ask the ECHR to revise its 1978 judgement.[5]

In March 2018, the ECHR announced a 6–1 decision against revising the original judgement.[49] In September of the same year, the ECHR refused to consider the case before its Grand Chamber, meaning that the case cannot be appealed any longer.[50]

In 2021, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom found that the use of the five techniques amounts to torture.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Internment – Summary of Main Events. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ Joint Committee on Human Rights, Parliament of the United Kingdom (2005). Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters: Oral and Written Evidence. Vol. 2. The Stationery Office. p. 110. ISBN 9780104007662.

- ^ "Ireland v. United Kingdom – 5310/71 [1978] ECHR 1 (18 January 1978)". www.worldlii.org. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ a b 'British ministers sanctioned torture of NI internees' (5 June 2014)

- ^ a b "Government backs 'Hooded Men' torture case". RTÉ.ie. 2 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Judgement – In the matter of an application by Margaret McQuillan for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland) (Nos 1, 2 and 3) In the matter of an application by Francis McGuigan for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland) (Nos 1, 2 and 3) In the matter of an application by Mary McKenna for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland) (Nos 1 and 2)" para. 186–188

- ^ a b c "Today in Irish History, 9 August 1971, Internment is introduced in Northern Ireland". 10 August 2012.

- ^ McKittrick, D & McVea, D. Making Sense of the Troubles: The Story of the Conflict in Northern Ireland. London, Penguin, 2000 p. 67. [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Internment explained: When was it introduced and why?". The Irish Times.

- ^ a b "Today in Irish History, 9 August 1971, Internment is introduced in Northern Ireland". 10 August 2012.

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's ordeal 1966–1996 and the search for peace. London: Hutchinson. p. 126 Internment – Summary of Main Events

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. p. 131.

- ^ Parker, Tom. Frontline: "Is torture ever justified?". PBS.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace.

- ^ McGuffin, John (1973), Internment!, Anvil Books Ltd, Tralee, Ireland, pg 23.

- ^ Dickson, Brice (March 2009). "The Detention of Suspected Terrorists in Northern Ireland and Great Britain". University of Richmond Law Review. 43 (3). Archived from the original on 15 May 2013.

- ^ The Compton Report, November 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ a b c d e f Internment: A chronology of the main events. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ Danny Kennally and Eric Preston. Belfast August 1971: A Case to be Answered. Independent Labour Party, 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ^ Danny Kennally and Eric Preston. Belfast August 1971: A Case to be Answered. Chapter: Treatment of Arrested. Independent Labour Party, 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ^ "Former internees claim 'new evidence' of Army torture". BBC News. 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b McKittrick, David. Lost Lives: The stories of the men, women and children who died through the Northern Ireland Troubles. Mainstream, 1999. p. 80

- ^ "Blunt weapon of internment fails to crush nationalist resistance". An Phoblacht. 9 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland: 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ a b c d e f Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's ordeal 1966–1996 and the search for peace. Palgrave, 2002. p. 152

- ^ "Violence ebbing in Northern Ireland". The Milwaukee Journal, 13 August 1971.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace. pp. 189–191. ISBN 978-1-60127-067-2.

- ^ Hayes, Maurice (1995). Minority Verdict. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 132.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. p. 351.

- ^ Hamill, D. Pig in the Middle: The Army in Northern Ireland. London, Methuen, 1985, p. 63. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. pp. 178–180. ISBN 978-1-60127-067-2.

- ^ a b The Guineapigs by John McGuffin (1974, 1981). Chapter 4: The Experiment.

- ^ The Guineapigs by John McGuffin (1974, 1981). Chapter 6: Replay.

- ^ "Prisoners in Northern Ireland 'subjected to waterboarding by British army officers'". The Telegraph. 22 December 2009.

- ^ John McGuffin (1974, 1981).The Guineapigs. Chapter 9: Down on the Killing Floor.

- ^ The Parker Report, March 1972. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ a b Ireland v. the United Kingdom Paragraph 101 and 135

- ^ Susan McKay. "The torture centre: Northern Ireland's 'hooded men'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Irish Times". 15 July 1971.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. pp. 141/2. ISBN 978-1-60127-067-2.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-60127-067-2.

- ^ Smith, William Beattie (2011). The British State and the Northern Ireland Crisis. Washington DC: US Institute of Peace. p. 214.

- ^ Security Detainees/Enemy Combatants: U.S. Law Prohibits Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Footnote 16

- ^ Weissbrodt, David. Materials on torture and other ill-treatment: 3. European Court of Human Rights (doc) html: Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788–94 (Eur. Comm'n of Hum. Rts.)

- ^ "Ireland v. The United Kingdom – 5310/71 (1978) ECHR 1 (18 January 1978)".

- ^ "Secret Ballykelly interrogation centre unveiled". BBC News. 6 August 2013.

- ^ "British government authorised use of torture methods in NI in early 1970s". BBC News (5 June 2014).

- ^ "Adams calls on Government to reopen 'Hooded Men' case". The Irish Times (5 June 2014)

- ^ Keena, Colm. "European court shies away from torture finding in 'hooded men' case". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (11 September 2018). "Human rights judges reject final appeal of Troubles 'hooded men'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- 1971 in Northern Ireland

- British Army in Operation Banner

- Conflicts in 1971

- Human rights abuses in the United Kingdom

- Internments by the United Kingdom

- Military operations in Northern Ireland involving the United Kingdom (1969–2007)

- Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland

- The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

- Torture in the United Kingdom

- August 1971 in the United Kingdom