Henry Bond

Henry Bond | |

|---|---|

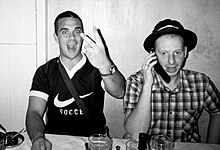

Bond in 2010 | |

| Born | June 13, 1966 London, England |

| Education | Goldsmiths, University of London |

| Known for | Photography |

| Notable work | Documents Series 26 October 1993 |

| Movement | Young British Artists Relational Aesthetics |

Henry Bond, FHEA (born 13 June 1966)[1] is an English writer, photographer, and visual artist. In his Lacan at the Scene (2009), Bond made contributions to theoretical psychoanalysis and forensics.

In 1990, with Sarah Lucas, Bond organised the art exhibition East Country Yard Show, which was influential in the formation and development of the Young British Artists movement; together with Damien Hirst, Angela Bulloch, and Liam Gillick, the two were "the earliest of the YBAs."[2]

Bond's visual art tends to appropriation and pastiche; he has exhibited work made collaboratively with YBA artists including a photograph made with Sam Taylor-Wood and the Documents Series, made with Liam Gillick. In the 1990s, Bond was a photojournalist working for British fashion, music, and youth culture magazine The Face. In 1998, his photobook of street fashions in London The Cult of the Street was published. His Point and Shoot (Cantz, 2000), explored the photo-genres of surveillance, voyeurism and paparazzi photojournalism.

In 2007, Bond completed his doctoral research; in 2009, he was appointed Senior Lecturer in Photography at Kingston University.

Life and career

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]

Henry Bond was born in Forest Gate in East London in 1966.[3] He attended Goldsmiths at the University of London, graduating in 1988, from the Department of Art,[4] with fellow alumni Angela Bulloch, Ian Davenport, Anya Gallaccio, Gary Hume, and Michael Landy—each of whom was to participate in the YBA art scene.

Bond attended Middlesex University in Hendon[5] studying for an MA in Psychoanalysis, where he was taught by Lacan scholar Bernard Burgoyne.[6]

Critical writing

[edit]Lacan at the Scene

[edit]

Lacan at the Scene is a work of non-fiction by Bond, published in 2009 by MIT Press. The book consists of interpretations of forensic photographs from twenty-one crime scenes from 1950s and 1960s England.[7] The thesis put forward in the book is that homicide can be considered in terms of Jacques Lacan's tripartite psychological model, thus any murder can be classified as either neurotic, psychotic, or perverse.[8] Bond's approach is closely linked to Walter Benjamin's assertion that, "photography, with its devices of slow motion and enlargement, reveals the secret. It is through photography that we first discover the existence of the optical unconscious, just as we discover the instinctual unconscious through psychoanalysis."[9]

Lacan at the Scene is an interdisciplinary study which is simultaneously an application of the theories of Jacques Lacan in relation to offender profiling and an inquiry into the nature and essence of photography.[10]

Bond's book considers the effects of photography on the spectator, the photographer and the photographic subject. He refers to a wide range of contextual material including "J.G. Ballard, William Burroughs, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre and Slavoj Žižek ... and the films of Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell, Michelangelo Antonioni, David Lynch and Christopher Nolan, among many others."[11] The book contains a foreword essay The Camera's Posthuman Eye by the Slovenian philosopher and critical theorist Slavoj Žižek.

Many of the photographs reproduced in the book are sexually explicit—they depict murder victims who were raped or tortured before the killing.[12]

Describing his research, in a 2007 interview, Bond said, "the press reporter's access to a crime scene is restricted, it is literally blocked by the ubiquitous black and yellow tape emblazoned with the exhortation: CRIME SCENE DO NOT CROSS. The photographs that I have worked with are documents made in a place that the press photographer or reporter cannot go."[13]

Critical reception

[edit]The critical reception of Lacan at the Scene was positive including reviewers commending the book as 'insightful', 'ground-breaking', 'audacious' and 'enthralling' – writing in the peer-reviewed journal The European Legacy, Viola Brisolin said, ''Lacan at the Scene is a brilliant, ground-breaking work that will appeal to cultural practitioners and theorists, and to everybody interested in the dialogue between psychoanalysis and visual studies."[14] Writing in the peer-reviewed academic journal Philosophy of Photography, Margaret Kinsman said "Bond's exploration ... reminds us of just how used to order we are and how shocking and easy its dissolution is ... his approach evokes a kind of aesthetic pleasure, which unsettles even as it satisfies."[15]

Emily Nonko's review said, "Lacan at the Scene ultimately presents a complex dynamic between both psychoanalysis and medium of the camera, the way that photography permits the viewer to delve into both the murder's mind and the victim's corpse, the psychological as well as the corporeal."[16]

Reviewing the book for Time Out New York Parul Sehgal said: "While Bond's interpretations occasionally strain credulity, his sensibility enthralls. His goal isn't police work per se, but to reveal how humble objects at the margins of crime scenes become powerfully allusive and lend themselves to a narrative."[17]

Daniel Hourigan, writing for Metapsychology Online Reviews said, "for the vast majority of the discussions in the more applied third, fourth, and fifth chapters, Lacan at the Scene enjoys a lucid and precise execution. The early chapters help to bring together the theoretical, discursive, and political elements that make these later chapters capable of pursuing such a rigorous and insightful project."[18]

The Gaze of the Lens

[edit]In July 2011, Bond's second book on the theory and philosophy of photography, The Gaze of the Lens, was self-published using the Kindle direct publishing format; the book consists of one hundred "concise observations and statements on photography."[19] In the book, Bond "activates, reconfigures, qualifies, and occasionally contradicts assertions made a diverse range of thinkers and practitioners including Rankin, Stieg Larsson, Antonioni, Charles Baudelaire, J.G. Ballard, Raymond Chandler, Walter Benjamin, Jacques Lacan, Georg Hegel and Slavoj Žižek."[19]

Street photography

[edit]A characteristic of Bond's style is his pastiche and appropriation of familiar types of photograph, for example, writing in Frieze, Ben Seymour said, "Bond carries on producing images of a homogenised, outside-less culture in a perpetual present of consumption which may be just ahead of, or self-consciously behind – but always deliberately in between – the conventions of advertising, fashion, surveillance or family photographs."[20] Bond has also considered his work in relation to the dérive – literally: "drifting" – theorised by Guy Debord and the city walks of the flâneur or psychogeographer.[21]

Characterizing his conception of street photography, in a 1998 interview, Bond said: "[For me street photography] is parallel to the psychoanalytic session, in that anything can be mentioned."[21] Bond began his street photography in the late-1990s and continued for approximately ten years concluding with his Interiors in 2005. Monograph books of Bond's street photography include two published in Germany – Point and Shoot (Ostfildern: Cantz) and La vie quotidienne (Essen: 20/21).

The Cult of the Street

[edit]

Bond's large book, The Cult of the Street, was published in 1998 by "posh West End gallery",[22] Emily Tsingou Gallery, London. The 274 photographs included in the book depict daily life in London in the mid-1990s. Many of the photographs included in the book were originally taken by Bond whilst shooting commissioned features for the style and culture monthly The Face—during the period that the magazine was art directed by Lee Swillingham and Stuart Spalding, 1995–1999.[23] The book includes a foreword essay, "A Response to the Photographs", by psychoanalyst and author Darian Leader. It has been suggested that the title of the book is a reference to the 1926 Siegfried Kracauer essay The Cult of Distraction.[24]

In 2002, a group of large-scale printed examples from The Cult of the Street were included in the Barbican Centre survey Rapture: Art's Seduction by Fashion Since 1970[25] and these were shown again, in 2004, at the Museum of London, in an exhibition titled, The London Look: Fashion from Street to Catwalk.[26]

Critical response

[edit]Reviewing the book for the British newspaper The Independent, fashion writer Tamsin Blanchard described the book as, "a rich social document of the way we dress—rather than the way fashion designers like to imagine we dress".[27]

Writing in his commentary on the influence of the Young British Artists, High Art Lite, the art historian Julian Stallabrass said, "The Cult of the Street is telling of many characteristics of High Art Lite and its engagement with mass culture and the media. It takes as its subject not just the conventions of the street but youth and their modes of display in shops, clubs, parties, restaurants and even private homes ... they don't do much, Bond's people; they shop, of course, persistently, and present themselves to each other and the camera, dance sometimes, but the book is composed above all of an intricate fabric of exchanged glances and gazes."[28]

Writing in the British contemporary art journal Art Monthly, critic David Barrett said, "[In The Cult of the Street] values and meanings are constantly on the slide, be they the meaning of wearing brown instead of black, Airwalk instead of Airmax or including the subject's shoes in full-length photographs instead of cropping them. Bond sets out to document these fleeting social codes while also attempting to ride roughshod over the accepted conventions of photography."[29]

Point and Shoot

[edit]

Bond's book of street photography Point and Shoot, was published by German fine arts publisher Hatje Cantz Verlag, in 2000; many of the images included imitate forms of photography that are derided or taboo, such as voyeurism and paparazzi photojournalism; other images are grainy and suggest surveillance or CCTV images—the photographer is either an intrusive, prying, nuisance, or else reduced to an automaton-like spectator on daily life.

Printed examples from the book were exhibited in both commercial and museum gallery exhibitions, including a survey—selected and organised by curator Eric Troncy—which was on display at the contemporary arts centre Le Consortium in Dijon, France, March through May 1999.[30]

Critical response

[edit]Writing in The Japan Times, in 2000, journalist Jennifer Purvis said, "Bond elicits a film noir quality from a city that prides itself on the worst side of its nature. It is contemporary London in all its banality and beauty, portrayed in heavy, highly contrasted black-and-white photographs that evoke nostalgia more keenly than an old movie ... the images all speak of the life, London life, captured by a peering, voyeuristic Londoner."[31]

Reviewing the book in Frieze, the critic Benedict Seymour said, "Bond jumbles up his subjects—street scenes, shop windows, night-clubs, posh parties, backstage fashion shows, intimate portraits and sex club sybaritics—as well as the composition, with the apparent intention of throwing our will to categorise, and so comprehend the image, into disarray."[32]

In Germany, the book was awarded a Kodak Deutscher Fotobuchpreis in 2000.[33][34]

Interiors Series

[edit]

Bond's follow up to Point and Shoot, Interiors Series was published in Belgium, in 2005, by Fotomuseum Antwerp. The photographs included in the book appear to explicitly and deliberately invade the privacy of the subjects, who are captured—unaware of the presence of a photographer—at leisure, in their private dwellings. Writing in an essay accompanying the photographs, Bond said, "for me voyeuristic 'fixation' and the 'photographic act' have become inseparable. It is the sense of 'the illicit' that these photographs are leveraging. I must not be caught taking them, and in a way, the viewer of the photograph is included in my anti-social activity, they too are looking when they should not be."[35]

Exhibition organiser

[edit]East Country Yard Show

[edit]

In 1990, working together with Sarah Lucas, Bond organised the "seminal"[36] Docklands warehouse exhibition of contemporary art East Country Yard Show which was influential in the formation and development of the YBA art movement.[37]

Critical reception

[edit]In July 1990, reflecting on the East Country Yard Show and Gambler—a concurrent Goldsmiths-oriented warehouse show—in The Independent, art critic Andrew Graham-Dixon said, "over the past few months ... in terms of ambition, attention to display and sheer bravado there has been little to match such shows in the country's established contemporary art institutions."[38]

Writing in Artforum, art critic and curator Kate Bush said, "[Hirst's] Freeze anticipated a spate of do-it-yourself group shows staged in cheap, sprawling, ex-industrial spaces in recession-hit East London. Bond and Sarah Lucas's East Country Yard Show as well as Carl Freedman and Billee Sellman's Modern Medicine and Gambler, all in 1990, were, with Freeze, the shows that fuelled the myth of YBA as, paradoxically, both oppositional and entrepreneurial.[37]

Author Keith Patrick said, "[Following Freeze] many of the same artists showed again two years later in four artist-led exhibitions Modern Medicine, Gambler, the East Country Yard Show and Market ... although Freeze had been poorly attended and barely reviewed, these shows together became a symbol of a new artist-led entrepreneurship, a combination of calculated anarchy and an astute reading of the changing relationship of the artist to the market.[39]

Exhibit A

[edit]In 1991, Bond was invited by Julia Peyton-Jones to select an exhibition for the Serpentine Gallery; a curatorial project that became the 7 May – 7 June 1992, exhibition Exhibit A—a show on the theme of evidence and the scene-of-the-crime.[40] One of the works on view was a slide-installation, shown in a darkened room, by artist Mat Collishaw, which presented the viewer with a rapid-fire sequence of stills of Jodie Foster dancing as she appeared in the "rape scene", in Jonathan Kaplan's 1988 movie The Accused.[41] Writing in Volume II of the exhibition catalogue, art historian Ian Jeffrey said, "Exhibit A crystallises a turning in the art world away from the egotistical celebrity mode towards impersonality ... its premises are anonymous, fluent, vertiginous, wary of values."[42]

Selector and screenings

[edit]In 1990, Bond and fashion photographer Richard Burbridge guest edited a double issue of Creative Camera showcasing emerging British photographers—"The New New" issue, October–November 1990; the selection they made included the first published examples of photo-based artworks by Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst and Angus Fairhurst.[43][44] Bond's collaboration with the magazine continued as an ongoing series of artists' pages that ran as "openers"—appearing on the inside front cover and contents page. One spread, created by Hirst, depicted the mutilated corpse of a young man with wounds to the eyes, and was captioned 'Damien Hirst: Fig. 60 Self-inflicted injuries...'; another introduced Fairhurst's self-portrait 'Man Abandoned by Colour.'[45][46]

In 1993 through 1995, Bond organised a series of screenings of experimental film and video, Omron TV. The screenings were presented in bookable-by-the-hour Soho film preview theatres—including De Lane Lea (Dean Street) and The Soho Screening Rooms (D'Arblay Street); the project included presentations of works by Merlin Carpenter, the German artist Lothar Hempel, and the Slovenians Aina Smid and Marina Grzinic.[47]

Visual art practice

[edit]During the 1990s, Bond made numerous artworks which used appropriated visual material; in particular a series titled One Hour Photo which presented typical snapshots collected from wastebins of High Street photo-processing labs, across London.[48][49]

Bond also exhibited a collaboration with artist Sam Taylor-Wood, titled 26 October 1993, in which he pastiched the role of John Lennon as he had appeared naked, in a photo-portrait with Yoko Ono—shot by photographer Annie Leibovitz—a few hours before he was assassinated.

Writing on Bond's art practice, artist and critic Liam Gillick said: "Bond's art is fundamentally negotiated. No apparently given element of his subject at hand is allowed to proceed while maintaining any sense of an essentialist value. While on the surface his production may appear to re-present lucidly some chosen images of the world around us, it does so with a sceptical relationship to the way meaning is encoded and interpreted by us every day."[50]

Exhibition

[edit]In the early-1990s, Bond's work was included in two international survey exhibitions of contemporary art at Villa Arson, in Nice, France, No Man's Time in 1991, and Le Principe de réalité in 1993.[51]

In 1995, Bond was included in a group exhibition at the ICA, in London, titled Institute of Cultural Anxiety,[52] in which he presented archival material from the vaults concerning the events at an experimental gig by Einstürzende Neubauten which had taken place at the ICA in January 1984, and during which the group used jackhammers to drill into the stage.[53]

In the mid-1990s, examples of Bond's work were included in Brilliant! a survey of YBA art held at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in 1995, and Traffic, an exhibition introducing the Relational Aesthetics tendency, which took place at musée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux, France, through February and March 1996.

Other Men's Flowers

[edit]In 1994, Bond made a work using a letterpress printing press for a portfolio commissioned by Joshua Compston. The portfolio also included works by Gary Hume, Sam Taylor-Wood, and Gavin Turk. The title of the portfolio drew on a quote by the philosopher Montaigne ("I have gathered a garland of other men's flowers and nothing is mine but the cord that binds them."). For his part, Bond supplied a text which describes a series of views in Monaco, written in the style of a tourist guidebook. The portfolio was later acquired by Tate.[54] In 2010, the portfolio was exhibited at the Courtauld Institute.[55] Historian Elizabeth Manchester describes Bond's text as, "a page entirely filled with text apparently taken from a travel brochure or guide. It describes a fashionable and star-encrusted area in the south of France starting from the peninsula Cap Martin and including the Monte Carlo beach and the Riviera. Names of famous people, places and events, as well as geographical features, are capitalised for emphasis. The amenities provided by hotels, night clubs, casinos, museums and beaches, as well as a fish farm out at sea (producing the luxury fish, sea bass), are all named and occasionally described for the wealthy visitor."[56]

Documents Series with Liam Gillick

[edit]Between 1990 and 1994, Bond collaborated with artist Liam Gillick on their Documents Series a group of eighty-three fine art works which appropriated the modus operandi of a news gathering team, to produce relational art.[57] To make the work the duo posed as a news reporting team—i.e., a photographer and a journalist—often attending events scheduled in the Press Association's Gazette—a list of potentially newsworthy events in London. Bond worked as if a typical photojournalist, joining the other press photographers present; whilst Gillick operated as the journalist, first collecting the ubiquitous Press kit before preparing his audio recording device.[57]

Exhibition and collection

[edit]The series was first shown commercially in 1991, at Karsten Schubert Limited[58] and then, in 1992, at Maureen Paley's Interim Art[59] —two of the galleries that were pioneers in the development of the YBA art movement.

The duo's series was subsequently exhibited at Tate Modern, in the show Century City held in 2001,[60] and at the Hayward Gallery, in the exhibition How to Improve the World, in 2006.[61]

One example from the series, held in the Arts Council Collection, titled 14 February 1992, documents an auction of the contents of Robert Maxwell's London home at Sotheby's.[62] A further example records the former Governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, addressing the Tory Reform Group.[63]

Video works

[edit]Bond's videos are documents of action and events. Writing in his 1998 book Relational Aesthetics, Nicolas Bourriaud said, "video, for example, is nowadays becoming a predominant medium. But if Peter Land, Gillian Wearing and Henry Bond, to name just three artists, have a preference for video recording, they are still not 'video artists'. This medium merely turns out to be the one best suited to the formalisation of certain activities and projects."[64]

Exhibition

[edit]In 1993, Bond's short video work OTB was included in Aperto '93 at the Venice Biennale—a survey of international contemporary art.[65] The short—which was looped and shown on a multi-screen system—showed grainy black-and-white footage documenting a flâneur's-eye-view of the day-to-day coming and going aboard the plethora of crowded Vaporetto, the waterbuses, in Venice; Bond's deliberately down-to-earth perspective depicting humdrum daily life in the city was intended to oppose the iconic glamorised images of gondolas, etc.[66]

Between 1993 and 1994, "Bond made eight hours of video footage documenting his walks along the river Thames, resulting in a 26-minute film shown at the Design Museum, reformatted as inserts on Channel One, and finally as a book of stills, Deep, Dark Water."[67][68]

From July through September 1994, Bond's video works were showcased in an eponymous four-person exhibition at De Appel an art centre in Amsterdam—i.e., Deep, Dark Water (1994), Torch (1993), On the Buses (1993), Hôtel Occidental (1993), Big Shout (1993), The Burglars (1992/4), The Softly Softly (1994), Walked (1994)[69][70]—which was selected and organised by curator and theorist Saskia Bos (Dean of The School of Art at The Cooper Union, in New York).[71]

In 1995, Bond's video works were included in the Biennale de Lyon survey exhibition.[72]

Fashion photography

[edit]In the late-1990s and early-2000s, Bond contributed fashion editorial stories to The Face,[27] i-D,[73] Self Service,[74] Purple[75] and the now defunct Nova.[76]

One fashion photograph made by Bond, originally published in the March 2000 issue of The Face, depicted the model Kirsten Owen revealing her panties in a manner typical of the derided and recently criminalised (e.g., in the United States and Australia) voyeuristic "Uppie" or Upskirter.[77] In 2001, Bond was chosen by company director Roger Saul to photograph the commercial advertising campaign for a brand relaunch of Mulberry, a leather goods company—for which he used actors and celebrity couple David Thewlis and Anna Friel, as models.[78][79] Thewlis and Friel were reported to have been paid £50,000 to appear in the campaign.[80]

In 2008, examples of Bond's fashion photographs from this period were included in an international survey exhibition of contemporary photography selected by Urs Stahel, Darkside: Photographic Desire and Sexuality Photographed, held at Fotomuseum Winterthur—the Swiss national museum and collection of photography.[81]

Academic career

[edit]Bond was a research student at the University of Gloucestershire in Cheltenham Spa between 2004 and 2007; he received a doctorate in 2007.[82]

He teaches postgraduate photography, in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture, at Kingston University;[83] he is a Senior Lecturer in Photography, in the School of Fine Art.[84]

Personal life

[edit]Bond has stated that he is a person with autism – specifically Asperger syndrome. He has had both cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoanalysis for this condition.[85] In an article in The Guardian in 2012, Bond questioned the use of psychoanalysis with autistic children in France.[85]

Published works

[edit]Non-fiction

- The Gaze of the Lens (Seattle: Amazon KDP, 2011)

- Lacan at the Scene (Slavoj Žižek, series ed., Short Circuits; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)

Photography monographs

- Interiors Series (Antwerp: Fotomuseum, 2005)

- What gets you through the day (London: Art Data/Lavie, 2002)

- Point and Shoot (Ostfildern: Cantz, 2000)

- La vie quotidienne (Essen: 20/21, 1999)

- The Cult of the Street (London: Emily Tsingou Gallery, 1998)

- Documents (London: APAC/Karsten Schubert Limited, 1991)

- 100 Photographs (Farnham, Surrey: James Hockey Gallery, 1990)

Documentation of video works

- Safe Surfer (Lyon, France: Biennale de Lyon, 1995)

- Deep, Dark Water (London: Public Art Development Trust, 1994)

- Hôtel Occidental (Nice, France: Villa Arson, 1993)

Edited books

- Henry Bond and Sarah Lucas, East Country Yard Show (London: East Country Yard, 1990)

- Henry Bond and Andrea Schlieker, Exhibit A (London: Serpentine Gallery, 1992)

Essays in edited books

- "The Hysterical Hystery of Photography." In Urs Stahel (ed.), Darkside I: Photographic Desire and Sexuality Photographed, (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2008)

- "Comments on this Series." In Christoph Ruys (ed.), Henry Bond: Interiors Series (Antwerp, Belgium: Fotomuseum, 2005)

- "Montage My Fine Care: Five Themes with Examples." In Henry Bond & Andrea Schlieker (ed.), Exhibit A (London: Serpentine Gallery, 1992)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Henry Bond born 1966". Tate. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Archer, Michael, "Overlapping Figures. " In How To Improve the World: 60 Years of British Art, London: Hayward Gallery, 2006, p. 50, i.e., "Then later still there is the generation of Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Angela Bulloch, Henry Bond and Liam Gillick, the earliest of the yBas (young British artists)."

- ^ Henry Bond The Cult of the Street (London: Emily Tsingou Gallery, 1998) Unpag.

- ^ Ana Finel Honigman "Henry Bond in Conversation with Ana Finel Honigman," Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Saatchi Gallery, 10 July 2007.

- ^ "Middlesex University: MA Psychoanalysis". Mdx.ac.uk. 19 May 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Henry Bond, Lacan at the Scene (Cambridge, Mass. : The MIT Press, 2009), p. 200, footnote 31; p.220. footnote 20. A snippet view is available on Google books.

- ^ Andrea Walker Jacques Lacan: Detective and Cyborg The New Yorker, 19 June 2009.

- ^ Henry Bond, Introduction to Lacan at the Scene (Cambridge: MIT, 2009) p. 1.pdf available[permanent dead link] from MIT. Retrieved, 13 January 2012.

- ^ Henry Bond, 'Hard Evidence' in Lacan at the Scene (Cambridge: MIT, 2009) p. 23 pdf available[permanent dead link] from MIT.

- ^ Emily Nonko The Exquisite Corpse? Bomblog, 5 February 2010.

- ^ Josej Braun, Hop Scotch: CSI: Photography," Vue Weekly, Issue 745, 28 January 2010.

- ^ Parul Sehgal "Book Review: Lacan at the Scene," Time Out New York, Issue 738, 19–25 Nov 2009

- ^ Ana Finel Honigman, "Henry Bond in Conversation with Ana Finel Honigman," Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Saatchi Online, 10 July 2007

- ^ Viola Brisolin, "Lacan at the Scene" in The European Legacy, Volume 16, Issue 5, August 2011.

- ^ Margaret Kinsman, "The lure of the crime scene", Philosophy of Photography, London, Volume 1. Number 1, 2010., p. 116.

- ^ Emily Nonko "the Exquisite Corpse?" Bomb Magazine/Bomblog, 5 February 2010

- ^ Parul Sehgal, "Book review: Lacan at the Scene," Time Out New York, Issue 738, 19–25 November 2009.

- ^ Daniel Hourigan "Henry Bond: Lacan at the Scene," Metapsychology Online Reviews, posted 2 March 2010.

- ^ a b Unattributed, "MIT Published Author Switches to Kindle Direct Publishing-Platform", Artdaily, 19 August 2011.

- ^ Ben Seymour, "Review: Henry Bond" Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Frieze, Issue 54, October 2000

- ^ a b Stephan Schmidt-Wulffen, Henry Bond in Conversation with Museum Director Stephan Schmidt-Wulffen. In, Henry Bond: The Cult of the Street. London: Emily Tsingou Gallery, 1998, unpaginated.

- ^ Jonathan Jones, Keith Coventry: Emily Tsingou Gallery, The Guardian, 26 September 2000.

- ^ See, for example: Tony Naylor, "Thieves Like Us", [a story on anarchist group Decadent Action] The Face, 9/1997, p. 124–28. Facsimile available of p. 124–25 Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine; Siân Pattenden, "Fitter, happier, more productive?" The Face, 3/1998, p. 170–74. Facsimile available of p. 170–71 Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stallabrass (1999)p.134.

- ^ Chris Townsend (ed.) Rapture: Art's Seduction by Fashion Since 1970 (London: Barbican Art Gallery/Thames and Hudson, 2002). Overview on Google books

- ^ Chris Breward & Edwina Ehrman (ed.) The London Look: Fashion from Street to Catwalk (Newhaven: Yale University Press, 2004); Overview on Google books

- ^ a b "Tamsin Blanchard, "Everyday people." In The Independent, May 16, 1998". The Independent. London. 16 May 1998. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Julian Stallabrass, High Art Lite (London: Verso, 1999), p.133. The complete section in Stallabrass is on Google Books here [1]

- ^ "David Barrett, "Henry Bond at Emily Tsingou Gallery," Art Monthly, June 1998, p.33". Royaljellyfactory.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Le consortium Exhibitions archive

- ^ Jennifer Purvis, "Capturing private moments of a gritty London," The Japan Times, 11 November 2000

- ^ Benedict Seymour, "Review: Henry Bond" Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Frieze, Issue 54, October 2000

- ^ Photonews: Zeitung für Fotografie, Hamburg, Germany, May 2000.

- ^ "Hatje Cantz Verlag Prämierte Büche, retrieved, 28 March 2010". Hatjecantz.de. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Henry Bond "Comments on this Series", in Christoph Ruys (ed.) Henry Bond: Interiors Series (Antwerp: Fotomuseum, 2005), p. 6.

- ^ "Anya Gallaccio" Archived 7 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The British Council. Retrieved 14 March 10.

- ^ a b Bush, Kate. "Young British art: the YBA sensation", Artforum, June 2004, p. 91. Retrieved from findarticles.com, 14 March 2010.

- ^ Andrew Graham-Dixon, "The Midas Touch?: Graduates of Goldsmiths' School of Art dominate the current British art scene", The Independent, 31 July 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Patrick, Keith (2000). "Foreword" in Sarah Bennett and John Butler (ed.), Locality, Regeneration & Divers[c]ities, Bristol: Intellect Books, 2000, p. 9

- ^ Andrea Schlieker, "Preface." In Bond and Schlieker (ed.), Exhibit A (London, Serpentine Gallery, 1992), p. 7.

- ^ Kate Bush, "Exhibit A", Art Monthly, June 1992, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Ian Jeffrey, "Exhibit A and the Everyday." In Henry Bond and Andrea Schlieker (ed.) Exhibit A, Vol. II, (London: Serpentine Gallery, 1992), p. 17.

- ^ See artists' pages, pp. 2–3; 16–45; and images accompanying scholarly essay, Andrew Renton, "Disfiguring: Certain New Photographers and Uncertain Images", pp. 16–21.

- ^ Also see the comments on that issue made by David Brittain in his Obituary of fellow Creative Camera editor, i.e., David Brittain, "Peter Turner 1947–2005," Afterimage, Sept–Oct 2005.

- ^ See: Creative Camera issues 309/310/311/312. A comprehensive database of the magazine contents on hwwilsonweb.com (athens signin required).

- ^ Facsimiles of the pages on Bond's archive, i.e., Hirst Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Issue 309, April–May 1991, pp. 2–3); Fairhurst Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Issue 312, October–November 1991, pp. 2–3).

- ^ See the material held on Bond at the Artist's Film and Video Study Collection which includes printed examples of the original flyers to the screenings. The project was also presented at Moderna galerija, Ljubljana—Slovenia's national museum of modern art—in 1994.

- ^ Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, "Someone Everywhere", Flash Art, Summer 1991. pp. 106–110. In particular, Christov-Bakargiev states, "The pictures were not taken by Bond himself, and were instead collected by him at photo labs from among those rejected or never picked up by the shops' clients." (p. 106).

- ^ Tony White, "East Country Yard Show", Performance, September 1990, p. 60; White states, "...snap-shots from the dustbins of 24-hour processing labs."

- ^ Liam Gillick, "Keeping the River in Mind." In Henry Bond/Angela Bulloch, Documentary Notes (London: Public Art Development Trust, 1996), p. 6.

- ^ Bond Villa Arson Archive. Retrieved, 24 January 2012

- ^ "Arts for All," The Independent, 3 February 1995.

- ^ Stuart Morgan, "Stuart Morgan visits the Institute of Cultural Anxiety", Frieze, Issue 21, March 1995, p. 35. Also see: Alexander Hacke, "How to destroy the ICA with drills," The Guardian, Friday, 16 February 2007.

- ^ Tate collection: Henry Bond. Accessed, 27 November 2010.

- ^ Courtauld Institute Press: Exhibitionism: The Art of Display Archived 21 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed, 27 November 2010.

- ^ Elizabeth Manchester "Tate: Other Men's Flowers, Accessed, 13 November 2011

- ^ a b Henry Bond & Liam Gillick, "Press Kitsch", Flash Art International, Issue 165, July/August 1992, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Karsten Schubert (ed) Henry Bond and Liam Gillick: Documents (London: Karsten Schbert Limited, 1991.)

- ^ Maureen Paley (ed.) On: Henry Bond, Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick, Graham Gussin, Markus Hansen (London and Plymouth: Interim Art/Plymouth Arts Centre, 1992); also see Interim Art timeline Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Emma Dexter, "London 1990–2001." In, Iwona Blazwick (ed.) Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis (London: Tate, 2001), p. 84. Snippet view available on Google books.

- ^ "Century City Exhibition". Tate.org.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Bond and Liam Gillick (Bond (b. 1966), Gillick (b. 1964))&searchParameter2=487 Arts Council Collection Archived 14 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 21 November 2011

- ^ FRAC Poitou-Charentes Collection Accessed 21 November 2011

- ^ Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon, France: les Presses du réel, 1998), p. 46. A pdf of relevant extract is available at Hints.hu

- ^ "The British Council's Venice Biennale Timeline". Venicebiennale.britishcouncil.org. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Benjamin Weil, "Emergency." In Achille Bonito Oliva and Helena Kontova (eds.) XLV [45th] Biennale di Venezia: Aperto '93, Emergency/Emergenza (Milan: Giancarlo Politi Editore, 1993), ISBN 88-7816-053-9.

- ^ Jane Rendell, Art and Architecture: a place between (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), p. 64. Snippet view available on Google Books.

- ^ Henry Bond, Deep, Dark Water (London: Public Art Development Trust, 1994).

- ^ "De Appel exhibition archive, retrieved 25 March 2010". Deappel.nl. 10 September 1994. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ See the partial Filmography/Biographical CV held in the British Artists' Film and Video Study Collection.

- ^ http://www.allbusiness.com/finance-insurance-real-estate/real-estate/4410847-1.html All Business [unattributed] "The Cooper Union Appoints Saskia Bos Museum Director and Noted Curator to Head School of Art", 15 July 2005

- ^ Thierry Raspail (ed.) 3e Biennale de Lyon: installation, cinéma, vidéo, informatique (Paris: Seuil, 1995) p. 1950. Snippet view available on Google Books.

- ^ See, for example, the Bond spread in i-D, June 2006 ("The Horror Issue") captioned, "Armani modelled by contemporary art collector Helen Thorpe."

- ^ See, for example: "The Obsessions" in Self Service, Spring/Summer 2003, p. 62-79.

- ^ "Purple Archive (Issue#2 Cover story was photographed by Bond)". Purple.fr. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ See, for example: "Sloane Square", [Photographer: Henry Bond; Stylist: Nancy Rohde] Nova, Sept 2000

- ^ "Next Style/Fashion: We're Infatuated with it...", The Face, March 2000. p.156.

- ^ Tamsin Blanchard (28 October 2001). "Tamsin Blanchard, "Brand New Brand," The Observer, 28 October 2001". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Photos from Bond's Mulberry campaign Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine on Anna Friel official website.

- ^ Vogue.co.uk

- ^ "Exhibition information on e-flux". E-flux.com. 5 September 2008. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Ana Finel Honigman "Henry Bond in Conversation with Ana Finel Honigman," Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Saatchi Gallery, 10 July 2007. To wit: "These relationships are discussed in detail in the text of my PhD thesis. They don't really function as brief anecdotes. If your interest is aroused, then please refer to the complete text."

- ^ Kingston University Kingston University: Photography MA: Who teaches this course, accessed, 31 October 2010.

- ^ Kingston University Staff Directory, retrieved 09 04 2011.

- ^ a b Henry Bond "What autism can teach us about psychoanalysis,", The Guardian, 16 April 2012, accessed 17 April 2012.

External links

[edit]- List of books by Henry Bond held at the National Art Library, England.

- Artist's personal website: Henry Bond

- Tamsin Blanchard article

- Interview on Saatchi Blog with Anna Honigman

- Walker Art Center press release

- Facsimile invitation card to The Cult of the Street exhibition at Emily Tsingou Gallery, 13 May – 27 June 1998.

- Example from The Cult of the Street in the Swiss national photography collection at Fotomuseum, Winterthur.

- Frieze review

- Facsimile of invitation card to Point and Shoot exhibition at Emily Tsingou Gallery, 9 May to 30 June 2000.

- Lacan at the Scene

- 1966 births

- Academics of Kingston University

- Alumni of Goldsmiths, University of London

- Alumni of Middlesex University

- Alumni of the University of Gloucestershire

- Autistic artists

- Autistic writers

- Photographers with disabilities

- British art curators

- British conceptual artists

- British psychoanalysts

- English art critics

- English contemporary artists

- English male non-fiction writers

- English non-fiction writers

- Photographers from the London Borough of Newham

- Living people

- People with Asperger syndrome

- Street fashion

- Young British Artists

- Fellows of the Higher Education Academy

- English writers with disabilities

- British artists with disabilities

- People from Forest Gate